A Fragile Past: Exploring One Family’s Narrative Through the Photographs They Buried

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Between 1975 and 1979, Cambodia closed itself off to the world under the rule of the Khmer Rouge, an ultra-communist regime driven to purge the country of the corruption of the ruling elite and return it to an agrarian utopia. The reality, though, cost the lives of almost two million Cambodians through sickness, starvation, and murder.

As a photographer working intermittently in Cambodia since 2005, I have in recent years questioned the role of photojournalism in representing the nation’s traumatic history. In an extension of my practice, I began to gather found family images from the 1950s through the 1980s. I wanted to understand the daily life of this period before and after the Khmer Rouge regime, and to find a way to enable these important histories to be questioned, away from the media-dominated narratives. Interviews with family members about the photos provided the opportunity for the spaces and events within and around images to be discussed and contextualized. The result of my research with family photographs was the development of the Found Cambodia archive and the artist’s book Buried, showcased here.

Found Cambodia is an online archive that houses family images pre– and post– Khmer Rouge. In a reaction to the removal of historical artifacts from Cambodia, no original image is ever kept; photographs are only scanned or photographed and then presented together with background information from their owner. This action asserts the importance of the material image in cultural heritage. More than a hundred families are represented within the archive, with images coming to light often through conversation. Alongside the fragmented archives, there are moments when individual family collections are so complete that they warrant their own discussion. Buried is such an example.

Buried explores the narrative of the Rama family, who hold an intimate collection of images from before and after the Khmer Rouge. During the first two years under the regime, the Ramas buried their family photographs along with some jewelry. They were wrapped in a plastic bag and placed in a jar in the ground beneath their hut in Ou Sralou village, where they had been relocated by the Khmer Rouge from the city of Battambang. The family chose to hide the photographs because the village leaders would conduct random and unannounced searches, targeting “city people” as they looked for evidence that tied them to their lives before their relocation. After the Khmer Rouge killed the family’s father, Krishna Rama, in 1977, their mother, Kimpean Ky, dug up the photographs as she feared the rest of the family were under threat of execution. They fled to other villages in Battambang province, eventually making their way to refugee camps on the Thai border. During the family’s escape to the camps of Thailand, the photographs were water-damaged in the monsoon season of 1979. Some of the photographs were so damaged that the Ramas had to discard them. The Ramas continued to collect images of life in the camps and eventually of their resettlement in New Orleans, in the United States. Of the immediate family of nine, eight miraculously survived the conflict: Kimpean Ky (who passed away in December 2019) and her seven children, consisting of five sons, Monyrath, Vira, Raya, Sundaram, and Nadirak, and two daughters, Sundary and Ratha. I have worked closely with the family since 2015, slowly understanding their narrative and finding a suitable method of presenting the collection.

All of the extended captions are taken from conversations with Vira Rama. The handwritten captions were from Monyrath, Vira, Sundaram, Nadirak and their cousin Chandra. Vira has become the custodian for the family’s images; he also continues to photograph key family gatherings as a way of extending the family’s narrative.

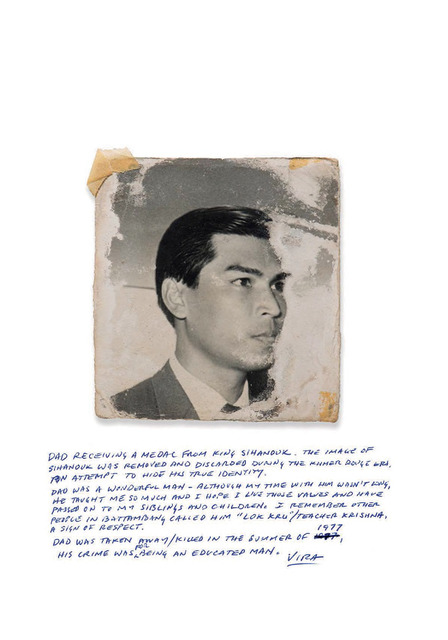

Fig. 1. Dimensions: 3.5 x 3.75 inches, Circa 1968. This image was taken in Battambang, when King Norodom Sihanouk visited the province. My Father was receiving a medal for his involvement in the sports program in Battambang City. The image we have today was actually a crop of a larger image, which was framed in the house. We cut this image of my father out, removing Sihanouk, when we reached the village of Ou Sralau in Battambang Province. It was important as the family did not want to show any association with the aristocracy. It was our fear that lead to this - to hide our identity. I don’t know who decided to cut the image but it was buried along with the rest of the family images within the first year of the Khmer Rouge. I still try to rationalise the idea of why we took these images with us. We thought that we would return to the city as the Khmer Rouge told us that the Americans were coming to bomb the city as they did in Phnom Penh, but we would return. As children we did not care about photographs but my parents did, maybe my parents knew we would not be returning to the city. My Mum lost her brother to the Khmer Rouge straight away, he was a solider for the Lon Nol government. My dad’s boss’s son-in-law who was a military doctor and also our family physician was also killed instantly... so maybe this was part of their rationale when they took the photographs with them. In time we started to realise these images would identify us, so we buried them in the village. I believe we took more to the village than we have now, but as the threat increased, we destroyed images that showed any affiliations with former government or with military uniforms/outfits.

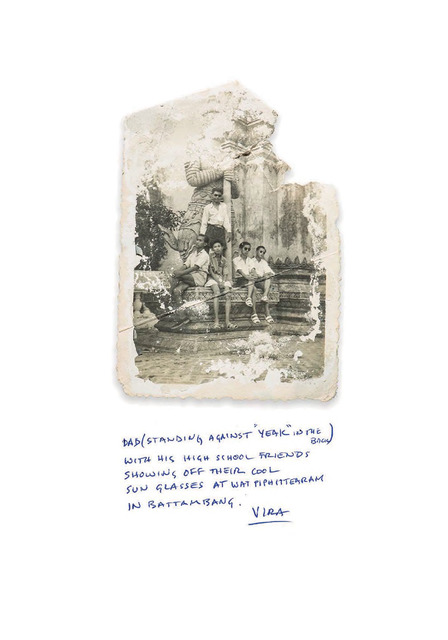

Fig. 1. Dimensions: 3.5 x 3.75 inches, Circa 1968. This image was taken in Battambang, when King Norodom Sihanouk visited the province. My Father was receiving a medal for his involvement in the sports program in Battambang City. The image we have today was actually a crop of a larger image, which was framed in the house. We cut this image of my father out, removing Sihanouk, when we reached the village of Ou Sralau in Battambang Province. It was important as the family did not want to show any association with the aristocracy. It was our fear that lead to this - to hide our identity. I don’t know who decided to cut the image but it was buried along with the rest of the family images within the first year of the Khmer Rouge. I still try to rationalise the idea of why we took these images with us. We thought that we would return to the city as the Khmer Rouge told us that the Americans were coming to bomb the city as they did in Phnom Penh, but we would return. As children we did not care about photographs but my parents did, maybe my parents knew we would not be returning to the city. My Mum lost her brother to the Khmer Rouge straight away, he was a solider for the Lon Nol government. My dad’s boss’s son-in-law who was a military doctor and also our family physician was also killed instantly... so maybe this was part of their rationale when they took the photographs with them. In time we started to realise these images would identify us, so we buried them in the village. I believe we took more to the village than we have now, but as the threat increased, we destroyed images that showed any affiliations with former government or with military uniforms/outfits. Fig. 2. Dimensions: 2.3 x. 3.4 inches, Circa 1955. My father is the young man standing at the back next to the statue of a Yeak. In Khmer folklore, Yeak is the presentation of evil. Yeak at the gate of the temple represent the defeat of evil by Buddha and the conversion of Yeak into a protector of Buddhism. Many temples in Cambodia have two of these statues at the gate as a symbolic guard. My father is with his school friends, my father’s school was near this temple, Wat Piphittearam. You can see they are very smartly dressed, sun glasses and matching shoes, they are not in uniform so I guess they were just hanging out. I believe this photograph was made around the mid 1950s – this was a very sophisticated period in Cambodia and Battambang was very much considered an artistic hub. My father was very involved in sport, he also played the accordion – the international styles and influences were very apparent. A lot of my father’s friends from this period were still close to my father as he grew into adulthood, they would stop by the house even when I was a child, but I don’t remember their names. Battambang was a small community, however it is the second largest city in Cambodia.

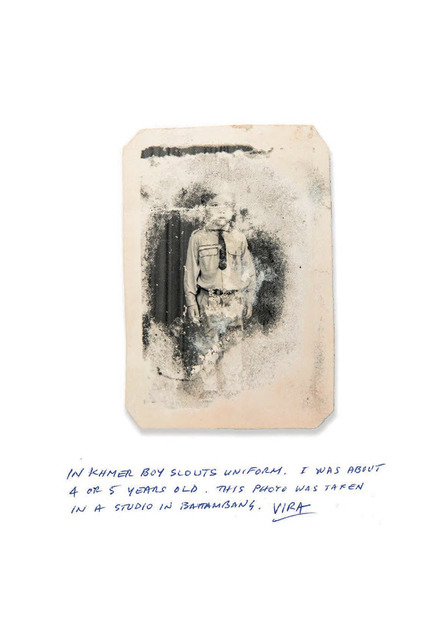

Fig. 2. Dimensions: 2.3 x. 3.4 inches, Circa 1955. My father is the young man standing at the back next to the statue of a Yeak. In Khmer folklore, Yeak is the presentation of evil. Yeak at the gate of the temple represent the defeat of evil by Buddha and the conversion of Yeak into a protector of Buddhism. Many temples in Cambodia have two of these statues at the gate as a symbolic guard. My father is with his school friends, my father’s school was near this temple, Wat Piphittearam. You can see they are very smartly dressed, sun glasses and matching shoes, they are not in uniform so I guess they were just hanging out. I believe this photograph was made around the mid 1950s – this was a very sophisticated period in Cambodia and Battambang was very much considered an artistic hub. My father was very involved in sport, he also played the accordion – the international styles and influences were very apparent. A lot of my father’s friends from this period were still close to my father as he grew into adulthood, they would stop by the house even when I was a child, but I don’t remember their names. Battambang was a small community, however it is the second largest city in Cambodia. Fig. 3. Dimensions: 2.5 x 3.75 inches, Circa 1969. This is a photograph of me as a young boy in my Khaki uniform of Yuvan – the national youth organization that was first formed by the French colonial power. I think King Norodom Sihanouk was visiting Battambang so we were given the day off school. We would line the streets and wave as he was driven past. The water damage on the photograph hides part of the uniform, such as the hat and there is a medal of King Norodom Sihanouk. The photograph was made in a studio on street number 2 in Battambang. There were mainly Chinese Khmer families in this area and there were a lot of businesses here too. I think I had this picture made to mark the visit of King Norodom Sihanouk either the same day as he visited or the day before.

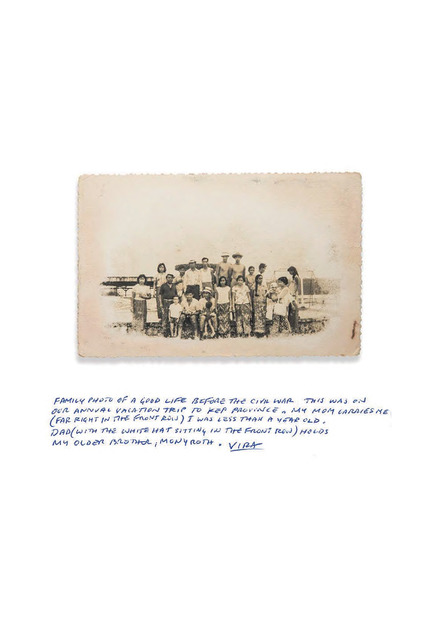

Fig. 3. Dimensions: 2.5 x 3.75 inches, Circa 1969. This is a photograph of me as a young boy in my Khaki uniform of Yuvan – the national youth organization that was first formed by the French colonial power. I think King Norodom Sihanouk was visiting Battambang so we were given the day off school. We would line the streets and wave as he was driven past. The water damage on the photograph hides part of the uniform, such as the hat and there is a medal of King Norodom Sihanouk. The photograph was made in a studio on street number 2 in Battambang. There were mainly Chinese Khmer families in this area and there were a lot of businesses here too. I think I had this picture made to mark the visit of King Norodom Sihanouk either the same day as he visited or the day before. Fig. 4. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1966. When I make family photos now this type of picture is what I tend to avoid, these big group pictures, but then they are the ones I end up valuing the most. It shows the size of our family and this holds the most importance and significance to us as a family. This was during a vacation to Kep (Seaside resort in Cambodia). It shows the collection of both sides of the family; these trips happened every summer. Our family friends owned a house in Kep which we would stay in, it overlooked the ocean. When I last returned to Cambodia in 2010 we tried to find the location but I think it has gone now. The picture was taken by one of the small monuments or roundabouts in Kep. I was only six months old at the time. I have had to go to my mother when looking at some of these photographs to understand them, she still tells me a lot about them.

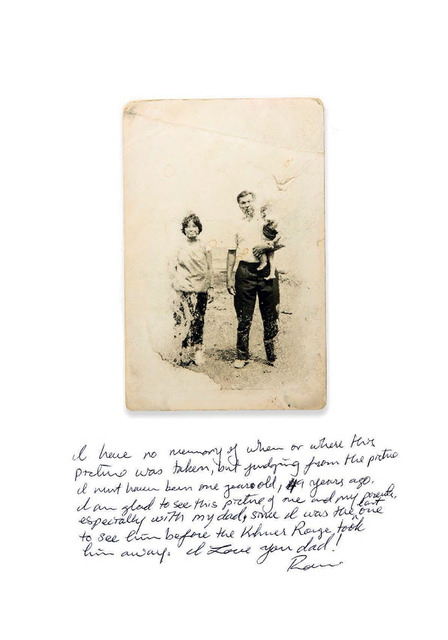

Fig. 4. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1966. When I make family photos now this type of picture is what I tend to avoid, these big group pictures, but then they are the ones I end up valuing the most. It shows the size of our family and this holds the most importance and significance to us as a family. This was during a vacation to Kep (Seaside resort in Cambodia). It shows the collection of both sides of the family; these trips happened every summer. Our family friends owned a house in Kep which we would stay in, it overlooked the ocean. When I last returned to Cambodia in 2010 we tried to find the location but I think it has gone now. The picture was taken by one of the small monuments or roundabouts in Kep. I was only six months old at the time. I have had to go to my mother when looking at some of these photographs to understand them, she still tells me a lot about them. Fig. 5. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Circa 1969. This picture was taken in either Kep or Sihanoukville. This might be the only picture with just my parents and one of us children, I think this is why my brother Sam is so connected to this image. The picture is so damaged but it still creates such an emotional response with our family. We made a couple of extended holidays a year, they could be from any time from 1 to 2 weeks. I am not sure why we adopted this idea of the vacation; this was still in many ways a new experience; we were lucky we could afford it. I also wonder if there is some cultural influence on my father as he was half Indian and he had a very different global perspective. His friends were very global, the families who studied overseas and had the villas in Kep, we knew them, and this was part of the network which allowed us to stay in these places.

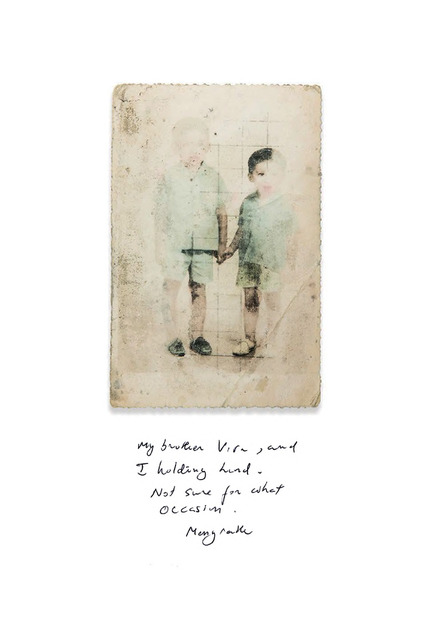

Fig. 5. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Circa 1969. This picture was taken in either Kep or Sihanoukville. This might be the only picture with just my parents and one of us children, I think this is why my brother Sam is so connected to this image. The picture is so damaged but it still creates such an emotional response with our family. We made a couple of extended holidays a year, they could be from any time from 1 to 2 weeks. I am not sure why we adopted this idea of the vacation; this was still in many ways a new experience; we were lucky we could afford it. I also wonder if there is some cultural influence on my father as he was half Indian and he had a very different global perspective. His friends were very global, the families who studied overseas and had the villas in Kep, we knew them, and this was part of the network which allowed us to stay in these places. Fig. 6. Dimensions: 3.5x5.5 inches, Circa 1967. I believe this is a hand tinted image, which was very popular in that period. The checked background came from me trying to copy the image in high school, I drew the grid as a way of tracing the image. I wanted to paint it onto canvas during high school, but I never finished it. I don’t know why I chose this one. I could not remove the lines; I don’t know if I damaged it or if it added value to the image over time. I saw this grid technique back in Battambang, I would walk to the art store and see them using this method to enlarge movie posters, but no one taught me this in the USA this was just from my memory.

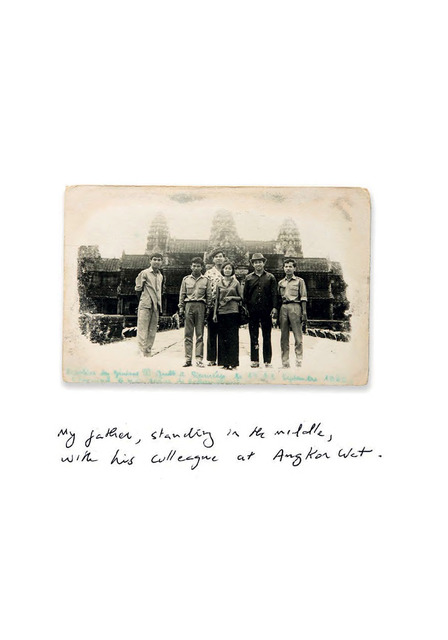

Fig. 6. Dimensions: 3.5x5.5 inches, Circa 1967. I believe this is a hand tinted image, which was very popular in that period. The checked background came from me trying to copy the image in high school, I drew the grid as a way of tracing the image. I wanted to paint it onto canvas during high school, but I never finished it. I don’t know why I chose this one. I could not remove the lines; I don’t know if I damaged it or if it added value to the image over time. I saw this grid technique back in Battambang, I would walk to the art store and see them using this method to enlarge movie posters, but no one taught me this in the USA this was just from my memory. Fig. 7. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, 1967/1968. In this image, we see my father and his colleagues, the men in safari suits were probably divers and security. I think this was from when my father visited a branch of the Bank he worked for, Bank Khmer du Commerce (BKC). These images were and still are common practice, everyone did this – to most Khmers, Angkor Wat is something to be proud of.

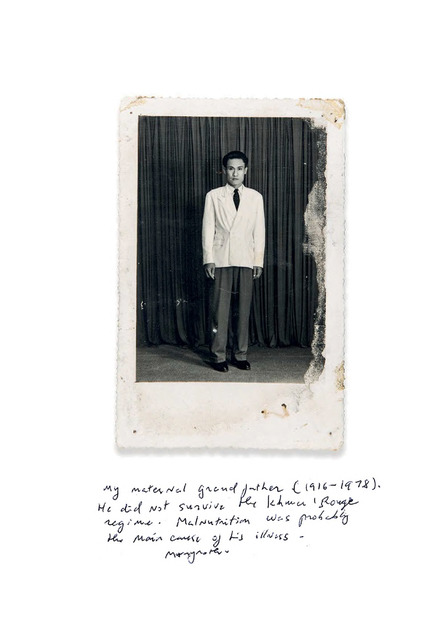

Fig. 7. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, 1967/1968. In this image, we see my father and his colleagues, the men in safari suits were probably divers and security. I think this was from when my father visited a branch of the Bank he worked for, Bank Khmer du Commerce (BKC). These images were and still are common practice, everyone did this – to most Khmers, Angkor Wat is something to be proud of. Fig. 8. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa mid 1950s. This is a picture of my grandfather; I think this image was made in the same studio as the one of me as a boy scout (image 3) on street No.2 in Battambang. I believe my family had a relationship with the owner of the studio so we kept going there. I only saw him in this clothing for special occasions, and he worked for the National Bank. He is almost pure Chinese despite being born in Cambodia. With Chinese name, features, and lighter complexion, this was an issue for him under the Khmer Rouge, as they despised any non-pure Khmer.

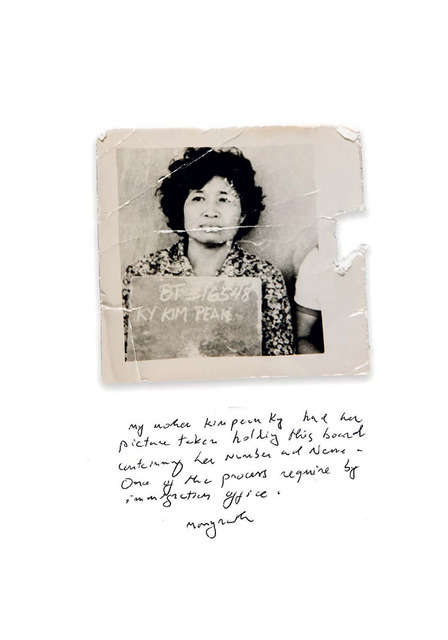

Fig. 8. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa mid 1950s. This is a picture of my grandfather; I think this image was made in the same studio as the one of me as a boy scout (image 3) on street No.2 in Battambang. I believe my family had a relationship with the owner of the studio so we kept going there. I only saw him in this clothing for special occasions, and he worked for the National Bank. He is almost pure Chinese despite being born in Cambodia. With Chinese name, features, and lighter complexion, this was an issue for him under the Khmer Rouge, as they despised any non-pure Khmer. Fig. 9. Dimensions: 2.5 x 2.5 inches, Early 1981. This photograph is of my mother. This was taken at the Panasnikhom Chonburi Transit Centre (Thailand), this was the start of the process of settling in the USA. We had received sponsorship and had moved from Khao-I-Dang Holding Centre on the Thai/Cambodian border. In the first camp we just had just a name and number, but this photograph to me is the first new identity that we had, this is the re-emergence of images, name and number. From all those vacation images to the Khmer Rouge flicking the switch to darkness, there was nothing after this, but this image was the start of our new identity even though my Mum looked sad we also had our identity back. When I read back the history of the camps I am unsure of what this meant but they called the camp a holding centre – there was a lot of debate during this time, many of the people who stayed in the camp without sponsorship were moved back to Cambodia after the signing of the 1991 Paris Peace Accord. I wonder if they classified us as refugee at this stage. There would have been a lot of pressure on the UN and Thailand, but then if the Khmer Rouge were still recognised by the west there could be a lot of conflict of the ideologies and the status of refugee.

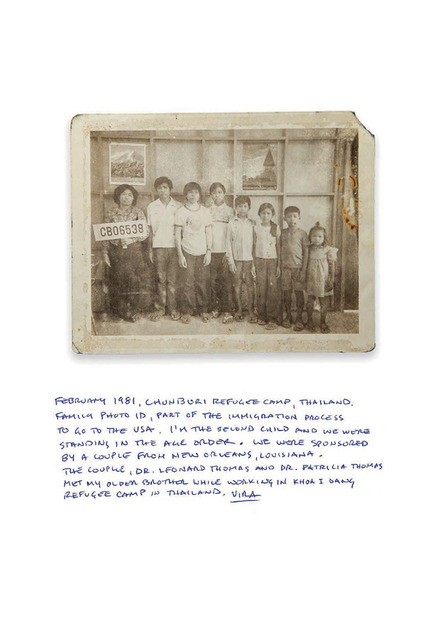

Fig. 9. Dimensions: 2.5 x 2.5 inches, Early 1981. This photograph is of my mother. This was taken at the Panasnikhom Chonburi Transit Centre (Thailand), this was the start of the process of settling in the USA. We had received sponsorship and had moved from Khao-I-Dang Holding Centre on the Thai/Cambodian border. In the first camp we just had just a name and number, but this photograph to me is the first new identity that we had, this is the re-emergence of images, name and number. From all those vacation images to the Khmer Rouge flicking the switch to darkness, there was nothing after this, but this image was the start of our new identity even though my Mum looked sad we also had our identity back. When I read back the history of the camps I am unsure of what this meant but they called the camp a holding centre – there was a lot of debate during this time, many of the people who stayed in the camp without sponsorship were moved back to Cambodia after the signing of the 1991 Paris Peace Accord. I wonder if they classified us as refugee at this stage. There would have been a lot of pressure on the UN and Thailand, but then if the Khmer Rouge were still recognised by the west there could be a lot of conflict of the ideologies and the status of refugee. Fig. 10. Dimensions: 3.4 x 4.2 inches, Early 1981. This was taken at Panasnikhom Chonburi Transit Centre (Thailand), this would have been made at the same time that we made the individual portrait, we had this group shot made first. When I look at it now I wonder why they chose this as the background and why they put the posters on the back? Were they trying to make the images a bit nicer? The staff were Thai workers who made the images and did the administration. In this camp we had no fear of the “Angkar” (Khmer Rouge) but in the border camps all the international staff left at night. We worried about attacks from across the border by the Khmer Rouge. When we first moved to the camp, there were just a few minor incidents caused by Khmer Rouge people. We heard there was a handful of Khmer Rouge in Khao-I-Dang. They didn’t feel safe there, so they eventually left the camp and moved to camp.

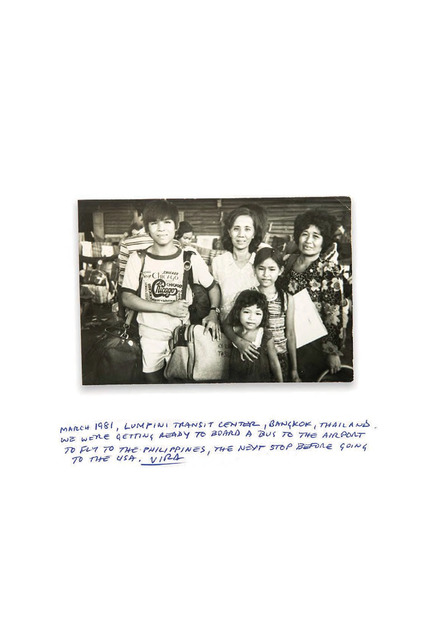

Fig. 10. Dimensions: 3.4 x 4.2 inches, Early 1981. This was taken at Panasnikhom Chonburi Transit Centre (Thailand), this would have been made at the same time that we made the individual portrait, we had this group shot made first. When I look at it now I wonder why they chose this as the background and why they put the posters on the back? Were they trying to make the images a bit nicer? The staff were Thai workers who made the images and did the administration. In this camp we had no fear of the “Angkar” (Khmer Rouge) but in the border camps all the international staff left at night. We worried about attacks from across the border by the Khmer Rouge. When we first moved to the camp, there were just a few minor incidents caused by Khmer Rouge people. We heard there was a handful of Khmer Rouge in Khao-I-Dang. They didn’t feel safe there, so they eventually left the camp and moved to camp. Fig. 11. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Early 1981. This was the final image at Lumpini Refugee Transit Centre in Bangkok, before we left Thailand to go to the Philippines to the Batann Refugee Processing Centre. You can see my Mum holding the immigration paperwork. The photo was taken by one of our sponsor’s friends. There was a lot of excitement during this time. There were a lot of religious organisations which would sponsor families and take financial responsibility; others were supported through families such as ours, but there was no guarantee in any of this. We have to remember that some people had no interest in going to the west, some just got caught up in heading west to get out of the camps to avoid war; but settling in the west was not of interest.

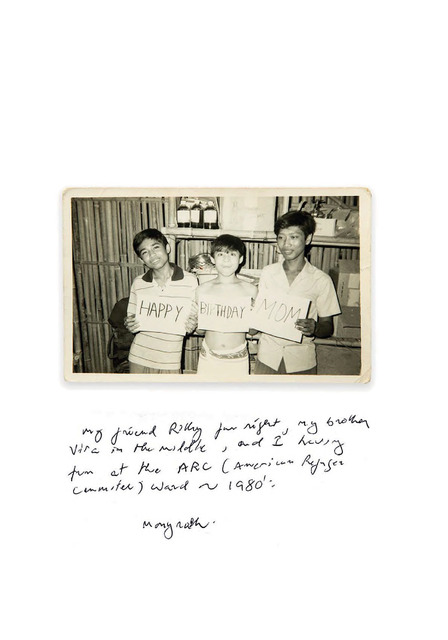

Fig. 11. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Early 1981. This was the final image at Lumpini Refugee Transit Centre in Bangkok, before we left Thailand to go to the Philippines to the Batann Refugee Processing Centre. You can see my Mum holding the immigration paperwork. The photo was taken by one of our sponsor’s friends. There was a lot of excitement during this time. There were a lot of religious organisations which would sponsor families and take financial responsibility; others were supported through families such as ours, but there was no guarantee in any of this. We have to remember that some people had no interest in going to the west, some just got caught up in heading west to get out of the camps to avoid war; but settling in the west was not of interest. Fig. 12. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Late 1980. The photograph was taken by one of the nurses at the Khao-I-Dang Holding Centre, she was from the USA. She wanted to make a picture to send home for her Mum for her birthday. I was in the middle (still wearing a towel from just having a shower). The photograph was made in the medical supply room, at the time I thought it was fun - I still look at it as fun. My brother, Monyroth, was working at the camp hospital; this is where we met our sponsors. These strangers had a massive impact on our destiny, I find it hard to put myself in their shoes, could I sponsor an entire family? They maybe saw something in us, but I don’t know. With all this killing and brutality, still there are people with good heart and humanity. What makes strangers reach out to help other people in desperate needs, it is their genuine compassion and want to make a better world.

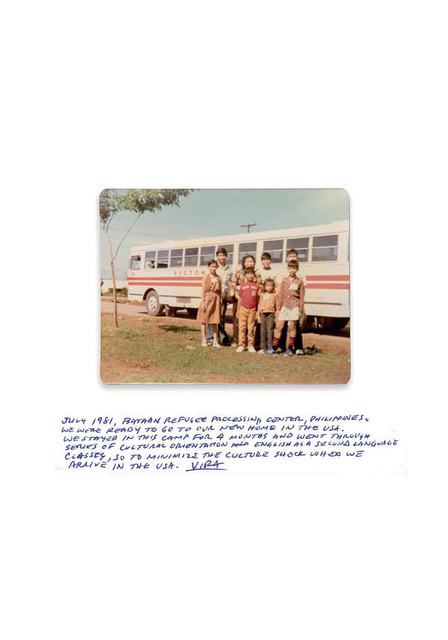

Fig. 12. Dimensions: 3.5 x 5.5 inches, Late 1980. The photograph was taken by one of the nurses at the Khao-I-Dang Holding Centre, she was from the USA. She wanted to make a picture to send home for her Mum for her birthday. I was in the middle (still wearing a towel from just having a shower). The photograph was made in the medical supply room, at the time I thought it was fun - I still look at it as fun. My brother, Monyroth, was working at the camp hospital; this is where we met our sponsors. These strangers had a massive impact on our destiny, I find it hard to put myself in their shoes, could I sponsor an entire family? They maybe saw something in us, but I don’t know. With all this killing and brutality, still there are people with good heart and humanity. What makes strangers reach out to help other people in desperate needs, it is their genuine compassion and want to make a better world. Fig. 13. Dimensions: 3.5 x 4.5 inches, Mid-1981. This was taken around noon time, you can see us squinting into the sun, you can see our ID tags, we were leaving Bataan Refugee Processing Centre (Philippines) and prepared for life in the USA. In this camp, we were taught basic cultural orientation skills: how to wait for the bus, stand in line, pay for the journey, how to use a laundromat – we had 6 months of orientation, we were taught English and aspects of American culture. The intention was to minimise culture shock when arrived in the USA.

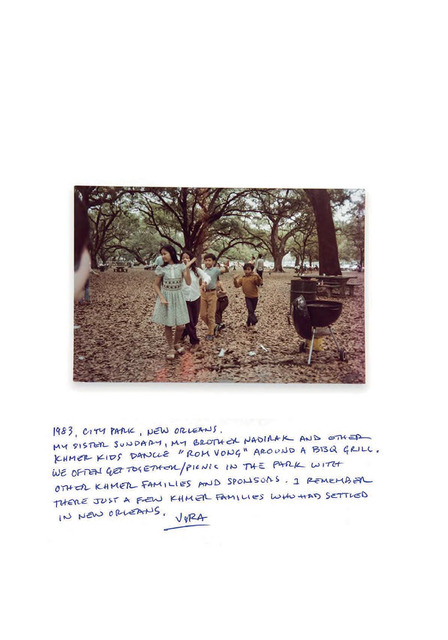

Fig. 13. Dimensions: 3.5 x 4.5 inches, Mid-1981. This was taken around noon time, you can see us squinting into the sun, you can see our ID tags, we were leaving Bataan Refugee Processing Centre (Philippines) and prepared for life in the USA. In this camp, we were taught basic cultural orientation skills: how to wait for the bus, stand in line, pay for the journey, how to use a laundromat – we had 6 months of orientation, we were taught English and aspects of American culture. The intention was to minimise culture shock when arrived in the USA. Fig. 14. Dimensions: 5.25 x3.5 inches, Circa 1983. This is a way for us to form a new community whilst in New Orleans. Looking at this picture now, of us with the other Cambodian children, I wonder what knowledge they had of Khmer Dance. They would not have seen any of this culture during the Khmer Rouge, but hearing the Khmer songs and being shown the movements by Khmer elders they would finally see their culture. Like any immigrant community you found a safe space, in culture, you want to learn things American, but you want to remember your own culture. As kids you are sensitive to this, to looking odd to Americans, them seeing you and thinking why they are doing this crazy dance? - but it’s culture and I see that now... but did not recognise that then.

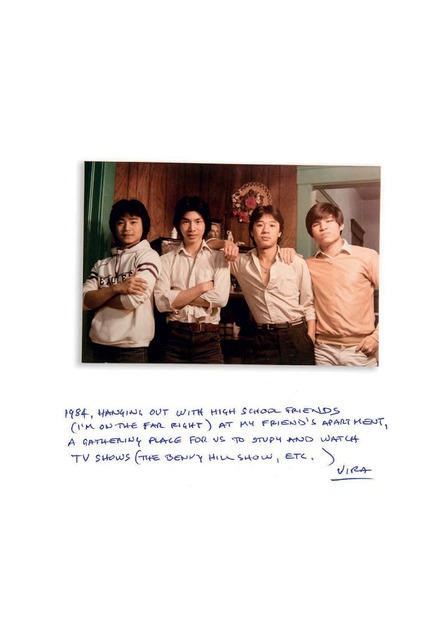

Fig. 14. Dimensions: 5.25 x3.5 inches, Circa 1983. This is a way for us to form a new community whilst in New Orleans. Looking at this picture now, of us with the other Cambodian children, I wonder what knowledge they had of Khmer Dance. They would not have seen any of this culture during the Khmer Rouge, but hearing the Khmer songs and being shown the movements by Khmer elders they would finally see their culture. Like any immigrant community you found a safe space, in culture, you want to learn things American, but you want to remember your own culture. As kids you are sensitive to this, to looking odd to Americans, them seeing you and thinking why they are doing this crazy dance? - but it’s culture and I see that now... but did not recognise that then. Fig. 15. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1984. These are my friends who I visited at their apartment, they had a camera and we made this photograph. They were all Vietnamese and refugees as well. We played soccer together, all the refugees hung out together. At school there were about 15 of us, the experience of being a refuge is what brought us together, like any teenager you wanted to be part of the group. This was our little South East Asian group, we would play soccer against other immigrants from Central America - Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala.

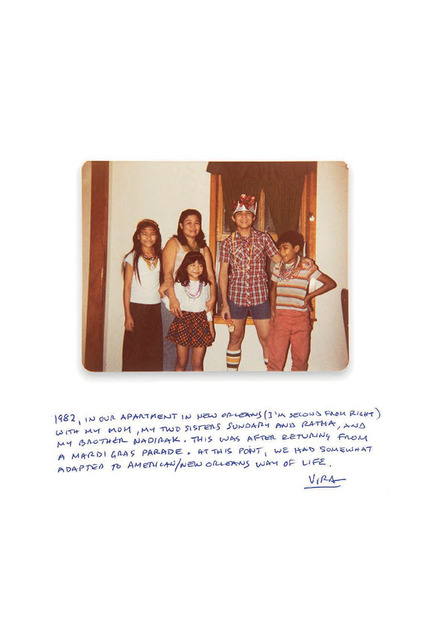

Fig. 15. Dimensions: 5.25 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1984. These are my friends who I visited at their apartment, they had a camera and we made this photograph. They were all Vietnamese and refugees as well. We played soccer together, all the refugees hung out together. At school there were about 15 of us, the experience of being a refuge is what brought us together, like any teenager you wanted to be part of the group. This was our little South East Asian group, we would play soccer against other immigrants from Central America - Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. Fig. 16. Dimensions: 4.5 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1982. We lived 2 blocks from a main road which was part of the Mardi Gras route. We would go and collect the beads, because we wanted to mix in the new culture. The Mardi Gras has become an important sense of our identity: the Louisiana way of life, the food, the southern hospitality has stuck with us. The darker history still resonates there but we hope we take the positive parts, we embrace the ‘big easy’. I feel very lucky we went to the south first, from the slow but dangerous Khmer Rouge, we were easily transitioned into the hot slow southern way of life but without the danger. We would have struggled in the fast-paced big city life of LA or another city. Our lives could have turned out differently.

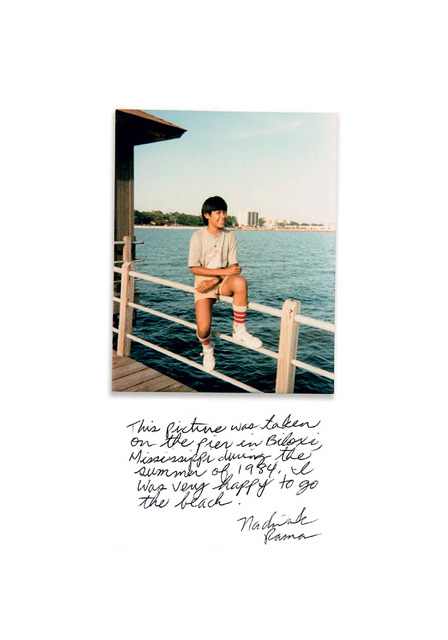

Fig. 16. Dimensions: 4.5 x 3.5 inches, Circa 1982. We lived 2 blocks from a main road which was part of the Mardi Gras route. We would go and collect the beads, because we wanted to mix in the new culture. The Mardi Gras has become an important sense of our identity: the Louisiana way of life, the food, the southern hospitality has stuck with us. The darker history still resonates there but we hope we take the positive parts, we embrace the ‘big easy’. I feel very lucky we went to the south first, from the slow but dangerous Khmer Rouge, we were easily transitioned into the hot slow southern way of life but without the danger. We would have struggled in the fast-paced big city life of LA or another city. Our lives could have turned out differently. Fig. 17. Dimensions: 3.5 x 4.5 inches, Summer 1984. This photograph was made in Biloxi, Mississippi. This image brings us happiness. We started with happy images from the past, we passed through some rough periods, then we move back into happiness and a bright future.

Fig. 17. Dimensions: 3.5 x 4.5 inches, Summer 1984. This photograph was made in Biloxi, Mississippi. This image brings us happiness. We started with happy images from the past, we passed through some rough periods, then we move back into happiness and a bright future.Charles Fox has worked as a photographer - predominantly in Southeast Asia with a particular focus on Cambodia - since 2005. His long-term projects are focused on the legacy of conflict. He also lectures on Photography at Nottingham Trent University.