Teaching the (Anti-)Extractivist Gaze

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

The Gaze, an exercise recipe for a group: A camera is set up on a tripod facing a chair. Our shortest and tallest participants sit in and we frame the shot for their median eye-level. Ostensibly it’s an exercise on interview set-up, and we’ve got one mic pointing at the chair and one mic facing behind, to another chair behind the lens. The participants leave the room, and I put a sticky note with “how do you see yourself?” on the camera’s rear. I put another sticky note with “how do you think others see you?” under the lens. One participant stays, presses record then sits facing the camera’s gaze. The next participant is sent in, instructed to sit behind the camera, ask the question they see there, and expect to be asked one. Then the ‘filmed’ sitter leaves, the ‘filmer’ moves into the camera-gaze, and the next participant goes in. The pattern continues until the first ‘filmed’ returns as the final ‘filmer,’ making a loop. We watch the clip back as an audience, and reflect together.[1]

Over the past decade I have used this exercise in the hope of prompting participants to a consciousness of how their filming is foremost a relational encounter, with ethical responsibilities. How do we feel when directed to sit and speak in the lens’ gaze? What are we asking of people when we film them? How do we feel as viewers, watching our own image and speech and the image and speech of our peers, on-screen? The exercise repeats multiple face-to-face encounters where participants assume roles of gazer and gazed-upon, interrogator and interrogee, participant and viewer, over just a few minutes. Emmanuel Levinas insisted the face-to-face encounter awakens responsibility for the Other,[3] which, in turn Brian Winston applied as “the central site of ethical behavior” in documentary: between “the filmmaker and those being filmed.” Winston equates this with the canonical ethical imperative to “do no harm” to either the filmed Others or the (more distant) spectating third-party.[4]

Teaching explicitly environmental documentary[5] brings both "do no harm" and the centrality of human-to-human ethics into question. More than "do no harm", environmental documentary implies a need for do good filmmaking; one active in shaping liveable futures. What of the ethics of the encounter between human filmmakers and the other-than-human? What of how relations are situated in Earth’s ecological mesh, of the countless Others who are none of filmed, filmer and viewer, but are nevertheless affected by the film-as-process? The life of each film (in conception, production, and dissemination) is a political and ecological actor; with some agency in shaping the world. If The Gaze exercise has some success in prompting participants to consider human ethics, what teaching might we conceive of to awaken or nurture responsibility, not only to the other-than-human in the camera’s gaze, but to the ecological beyond that tight triangle of filmer, filmed, and viewer?

But even when considering the human-to-human encounter of The Gaze exercise, filmmaking face-to-face does not seemingly necessarily awaken Levinas’s responsibility for the Other. Some respond candidly. Others refuse: “How do you see yourself?” “In a mirror.” While the camera-eye stays identical, the gaze changes according to who sits before and behind the camera, their relations at that moment, and between those selves and their context – the recording equipment, their peers, myself as their tutor, the space, the institution, the dominant cultures of that place. The gaze of the camera is altered by the situated quality of each self’s experience, including their cultural and biological inheritances. As Donna Haraway emphasises, “it matters what relations relate relations.”[6] What has the gaze become when it is refused? Refusal suggests a fear of exposure. Will I betray myself to you? What will you do with me? What will viewers think of me? Rather than awakening obligation and care, we fear the gaze takes something, to be exploited for the gazer’s benefit, or those behind them. We fear, or sometimes know, the gaze is extractivist.

Extractivism is a term which has evolved. Coined in the 1990s to describe the extraction of material resources from colonised lands for the profit of the coloniser, Naomi Klein expanded its meaning to describe “a dominance-based relationship with the Earth.”[7] Today, extractivism is used to refer not only to (environmental) material extraction, but to (social) financial and labour extractivism, and (mental) cogitative extractivism; the connecting principle being that value is extracted for metropole accumulation without attendant obligations to marginalised land, people and minds (human or otherwise).[8]

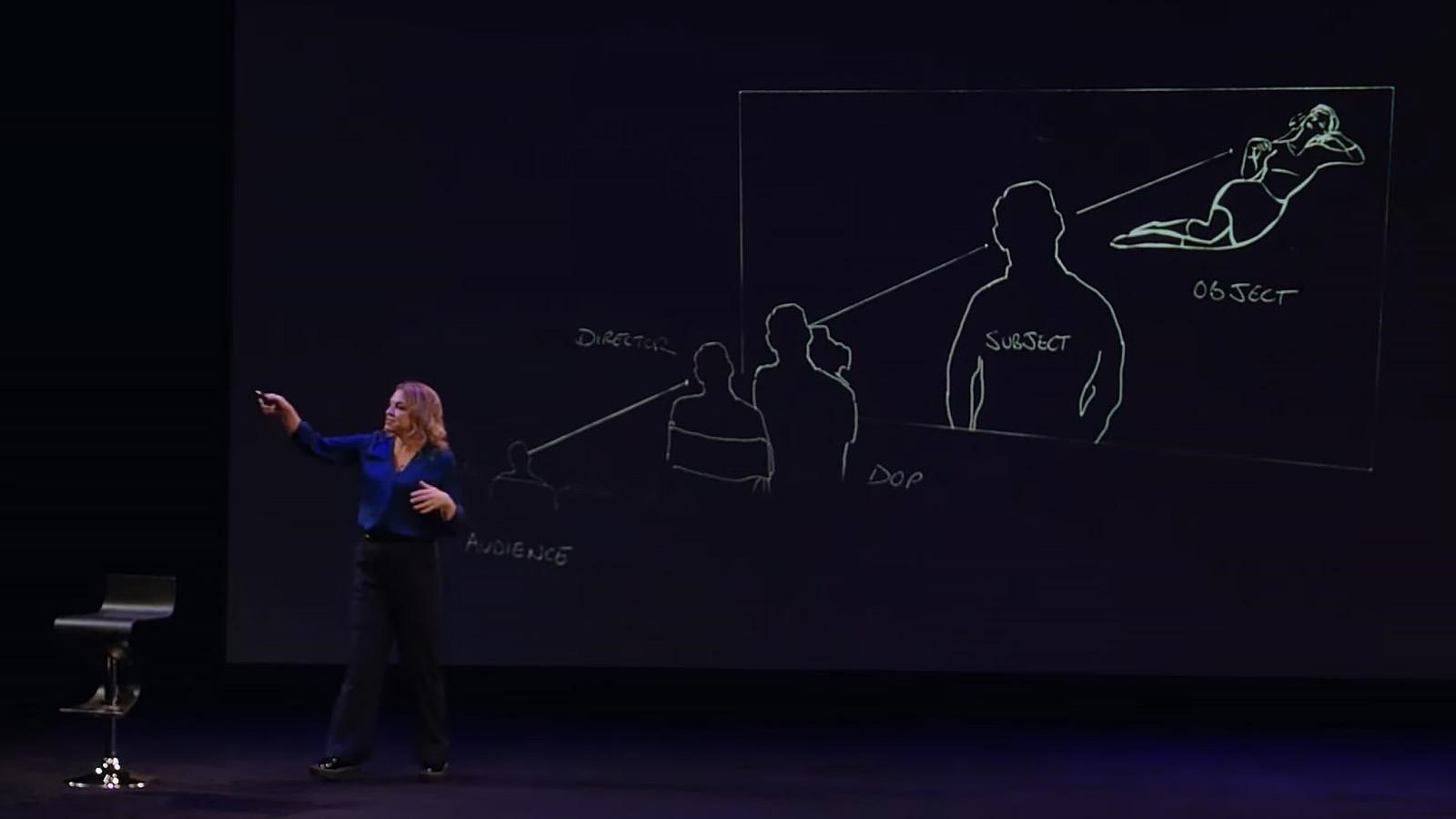

A myth endures that “cinema is, by nature, extractive and predatory.”[9] Is this essentialist reading warranted? While documentary recording equipment was invented by extractivist cultures and has been predominantly used as an extractivist tool, does this render such use inherent or merely expressive of those who used it so far? Before writing this, I’d never taught my students the genealogy and provenance of their equipment and ways of working - its origin in European settler-imperial industrial practices of resource-extraction, and its attendant mechanisms of enclosure, colonialism, and militarism.[10] Nor that such legacies persist, with digital cinema likewise dependent upon rare-earth materials, fossil power, exploitative labour practices and more: “the extractivist underpinnings remain.”[11] Film language marches alongside: we talk of ‘shoots’, of ‘capturing’ footage, ‘securing’ access; productions customarily organised in militaristic hierarchies. I recently attempted alternative terms with students, trialling ‘gathering’ over ‘shooting’. Not “this is what I want. I will hunt it,” but “this may be useful, we will gather it.” The students were receptive, but it’s hard to change speech-habits, or to find a readily understood replacement for ‘shot’. But perhaps such an exercise, at minimum, starts signposting extractivist inheritances and offering alternatives.

Alternatives are also prompted by the projects students propose. They regularly pitch work relating to queer and feminist themes, and (less-so) race, ableism and class. This provides a break that asks whose gaze has the camera-gaze been? I point students toward Laura Mulvey’s identification of the cinematically dominant “male gaze.”[12]

Not only has that gaze been heteropatriarchal, it has also been bourgeois,[13] white,[14] able-bodied,[15] settler-colonial,[16] and emanating from film cultures (extending into education) which celebrate individualistic filmmaking that extracts cinematic value for profit and/or status.[17] Macarena Gómez-Barris aggregates these gazes into “the extractive gaze.”[18] The filmmakers’ gaze has been situated all-but-exclusively in those privileged by capital to access and control recording, post-production, and distribution technologies.[19] From filmmakers to film educators to film students, we reproduce an extractivist gaze.

While the proliferation of recording devices (phones) offers an opportunity to elude the cultural grip of privilege and scope for “documentary resistance,”[20] extractivist approaches to cinema are so embedded that thinking beyond them can appear foolish. Hierarchical production structures, funding models, employment practices, auteurship, intellectual property, land ownership and access, editorial control, non-upgradable, non-repairable equipment, resolution-inflation, surveillance aesthetics... Where is the space to question these and other doxas in squeezed teaching schedules? If I do, will students dismiss me as a crank, pedalling concerns far abstracted from their desire to become filmmakers in the-world-as-it-is?

Fortunately, now-familiar discourses of justice and decolonisation provide a break inviting such discussion, and ‘extraction’ too has lately gained currency in documentary practice. The Documentary Accountability Working Group of nonfiction practitioners and scholars dismisses the inevitability of extractivist relations in documentary. DAWG teaches a reflective practice which attends to “how to make non-extractive, ethically responsible films.”[21] While DAWG calls for “an ecologically mindful and sustainable approach,”[22] the group is primarily concerned with human-to-human accountability. But their stress on reflection offers clues for how we might develop teaching for environmental documentary which promotes an anti-extractive gaze.

Back to this: “How do you see yourself?” “In a mirror.”

“Refusal turns the gaze back upon power”[23] say Eve Tuck and K Wayne Yang, referring to indigenous and other racialised communities’ refusal of research by settler-colonial universities. The researcher, or filmmaker, may believe their intentions benevolent, but it may be the code they are operating from – one which is invading, with the intention to extract – which is rejected. Refusal is then a mirror, the gaze bounced back to the researcher being refused, so they see nothing new, only themselves. It is, if I learn to see it, an invitation to reflection: on one’s own power, of the power of the code behind me, the systems and machines I am operating from. Is what I am making only a fetishizing of pain? Might I not deserve the refuser’s knowledge? Might my intervention not be that which is needed?

Tuck and Yang stress the importance and difficulty of seeing refusal. If difficult in human-to-human encounters like The Gaze, can we see refusal in environmental documentary? Can other-than-human selves, ecologies of selves, co-create? Or be said to consent, enable access, or refuse in a way we can see reliably? Much as we might yearn to be able to, the cogent answer has to be ‘No.’ But this absence does not render reflection meaningless. We might instead presume refusal, and continue by asking questions about our position as filmmakers. “Rather than chasing aims of objectivity, we encourage researchers to take up a stance of objection, one that will interrogate power and privilege, and trace the legacies and enactments of settler colonialism in everyday life.”[24] Tuck calls us to turn away from damage-centred research “that intends to document peoples’ pain and brokenness to hold those in power accountable for their oppression.”[25] Instead she offers a desire-centred framework which “accounts for the loss and despair, but also the hope, the visions, the wisdom of lived lives and communities,”[26] seeking to amplify and empower the desire with those being gazed upon. Yang offers a pedagogical practice I can bring into filmmaking teaching: asking students to present rushes of the spaces they intend to film, then intervening through techniques like erasing the foregrounded object to see what is unobserved, what observation is privileged, and asking questions including “How is (y)our research gaze damage-centered? ... What is a desire-centered (re)searching gaze?[27]

What might a desire-centred environmental documentary be? Again, beyond the human we hit communication problems, but perhaps those can be rendered accessible through what Anna Tsing calls “the arts of noticing”[28] and reflection. What actions by humans promote multispecies flourishing? Is that a generative flourishing, akin to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “braiding sweetgrass,”[29] of mutually beneficial human and more-than-human relationships, or a destructive one, like a harmful algal bloom? Is an environmental documentary we propose an appeal to an authority (powerful in the world-as-it-is and consequently invested in maintaining the status quo) or something which strengthens the power of those (human or not) in regenerative solidarity?

The task for educators is to engage learners with this awareness. Our concern is political ecology, that is, to teach a cinema that gifts insight into the political-ecological machinery that reproduces extractivism, and to teach a cinema that empowers other ways of being. This is to examine the gaze we have on the world, to identify then refuse extractivist genealogies, and to reflect the gaze back onto power, including our own. In so doing the gaze becomes something other: the oppositional gaze;[30] the female eye;[31] Agnes Varda’s gleaning eye.[32] Accessing what the anti-extractive gaze means is no easy task, so steeped in extractivist culture is life in general and filmmaking especially. But the clues are there in the breaks. We must teach bell hooks’ “transgressive image, the outlaw rebel vision... essential... for transformation;”[33] desire-centred, full of laughter, joy, thrills and hope. At stake is the possibility of documentary as an ethical practice. If we cannot teach a culture and aesthetics compatible with “ongoingness,”[34] powerful enough to take on now-dominant extractivist cultures, then documentary will have abrogated its responsibility as a shaper of worlds. It’s up to us to co-create a better filmmaking.

I am dreaming of an experiment in nonfiction filmmaking education, a long exercise, one I’m calling the Feral Film School. Two weeks, eight participants (paid if I can get the funding) camping up in the Cambrian Mountains in Cymru, making a film collaboratively using second-hand equipment, in a conscious effort to make anti-extractivist film. It’ll soon be a blueprint, then an imperfect reality, then a ruin. Then it will provide soil for other schemes to grow from, perhaps one day to flourish.[35]

James Staunton-Price is a SWWDTP-funded researcher in anti-extractivist nonfiction filmmaking education between Aberystwyth and UWE, in the commons of nonfiction film, political ecology, and education for eco-social change. James’ research is informed by his experience as a nonfiction artist-filmmaker and lecturer. He presently leads a BA documentary module at the London Film Academy.

I am indebted to filmmaker and researcher Ed Webb-Ingall, whose exercise How does it feel to be filmed/filming me? (2013-present; UK) provided inspiration, along with the installation / film I made with Lenka Clayton, Conversation (2006; London) https://vimeo.com/3106729. ↑

James Price, Hamish Galbraith, Duane Stewart, Linus Kent, Filippos Tzerras, Zachary Oladimeji, Zoya Schlamberger, Lizzy Lefebre, Christiaan Mitcalfe, Shreyas Dhapodkar, Kyle Williams, Ben Job and Alyssa Jouett, The Gaze London Film Academy (2023; London). ↑

Emmanuel Levinas, Entre Nous: On Thinking-of-the-Other (Entre Nous: Essais Sur Le Penser-a-l’autre), trans. Michael B. Smith and Barbara Harshav (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 63. ↑

Brian Winston, “‘Le Rapport de Face a Face’ in Digital Documentary,” Post Script 36, no. 2/3 (2017): 12–30. ↑

Like Tim Morton, I argue “all art is ecological” whether it purports to be or not. Timothy Morton, All Art Is Ecological (London: Penguin Books, 2021). ↑

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2016), 35. ↑

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (London: Penguin Books, 2015). ↑

What Eduardo Kohn describes as ‘semiotic selves’ Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). ↑

Anat Pick and Chris Dymond, “Permacinema,” Philosophies 7, no. 6 (2022): 122, https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060122. ↑

Nitrate film stock from guncotton; camera design from machine-gun technology; celluloid invented in 1868 with the addition of camphor, the same year British Navy ships bombarded Taiwan to seize control of the camphor trade. Sean Cubitt, Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017). Also Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2012). ↑

María Vélez-Serna, “Culture Beyond Extractivism: What Might a Post-Growth Cinema Look Like?,” Enough!, 9 February 2021, https://www.enough.scot/2021/02/09/culture-beyond-extractivism-what-might-a-post-growth-cinema-look-like-by-maria-antonia-velez-serna/. ↑

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6. ↑

Mark Fisher, “Classless Broadcasting: Benefits Street,” New Humanist, February 17, 2014, https://newhumanist.org.uk/4583/classless-broadcasting-benefits-street referencing Beverley Skeggs and Helen Wood, Reacting to Reality Television: Performance, Audience and Value (New York: Routledge, 2012). ↑

bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992), 122. ↑

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Ways of Staring,” Journal of Visual Culture 5, no. 2 (2006): 173–92, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412906066907. ↑

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research,” Qualitative Inquiry 20, no. 6 (2014): 812, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530265. ↑

This is analogous to the 1st and 2nd cinemas of Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, “Toward a Third Cinema,” Cinéaste, 4, no. 3 (1970): 1–10. ↑

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 124. Gómez-Barris is not exclusively speaking about a camera gaze, but a way of seeing. ↑

Pooja Rangan, Brett Story, and Paige Sarlin, “Humanitarian Ethics and Documentary Politics,” Camera Obscura 33, no. 2 (2018): 206, https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-6923166. ↑

Angela J. Aguayo, Documentary Resistance: Social Change and Participatory Media (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). ↑

I’m hugely indebted to DAWG’s work, but find 'non-extractive' a misnomer, only usable if we abandon the original, material sense of extractivism. DAWG et al., “From Reflection to Release: A Framework for Values, Ethics and Accountability in Nonfiction Filmmaking” (Documentary Accountability Working Group: 2022), 2, https://www.docaccountability.org/framework. ↑

DAWG et al., From Reflection to Release, 18. ↑

Tuck and Yang, Unbecoming Claims, 817. ↑

Tuck and Yang, 814. ↑

Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (2009): 409, https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15. ↑

Tuck, Suspending Damage. ↑

Tuck and Yang, 815. ↑

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 255. ↑

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013). ↑

hooks, Black Looks, 115. ↑

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, 124. ↑

Pick and Dymond, Permacinema, 4. ↑

hooks, Black Looks, 4. ↑

Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. ↑

Here I steal, with gratitude, from K Wayne Yang’s “other I” la paperson, A Third University Is Possible (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 70, https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452958460. ↑