Documentary Production as a Foundation for Climate Agency

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

In a recent University of Wisconsin Oshkosh symposium on politics and climate change, a panelist asked a group of undergraduates how many of them had been taught anything about climate change in their secondary education. Only a few students raised their hands. The week prior, the newly minted “Freedom of Expression” speaker series, funded by an alumni-donor organization, hosted renewable energy skeptic Robert Bryce.[1] This combination of lack of prior instruction in climate science, well-funded anti-renewable energy campaigns, and a tense political environment raises the stakes for instructors working to integrate climate education into their courses.[2] In this context, the process of documentary filmmaking provides valuable pedagogical tools to ground discussions of climate change in students’ observations and experiences. I begin by examining ways that producing documentary films helps students develop the situated knowledge necessary for climate agency. I then outline some of the challenges presented by the renewable energy skeptic’s visit and use this campus event to highlight the importance of the documentary publics produced by teaching environmental filmmaking.

In Spring 2023, I taught my department’s class in documentary production. I began the semester by inviting the campus Sustainability Director to give a brief presentation to the class outlining current issues on campus. Based on this information, students developed ideas for short documentary films. Students’ initial proposals addressed concerns such as recycling infrastructure, food waste disposal, a heating-system overhaul, and the role of student behavior in campus sustainability projects. The students then worked to refine these proposals into films with both an observational and interview component. As the students began searching for people on campus willing to let them observe their work, labor issues came into focus. Students wanted to contact—and learn from—grounds, facilities, and maintenance workers. The academic year had begun with the University administration’s decision to outsource custodial staffing to a private contractor, followed by a strike, and a re-commitment to continue to employ grounds and janitorial workers.[3] The combination of this politically charged background and the systemic over-allocation of custodial and facilities workers’ time, made it difficult for students to observe the people they identified as key actors in campus sustainability efforts. Unfortunately, rather than digging in and finding ways to incorporate these challenges into their films, students reconceived their projects to focus on more easily accessible processes including student recycling, on-campus hydroponic gardens, waste removal, and a falcon nesting project. These recalibrations of their initial ideas led us to reflect on the connections between labor, class, and participation in documentary films. While professors and administrators were more available to contribute to students’ films, the prompt to make observational documentaries led the students elsewhere—searching for those they felt were doing sustainability. Students’ awareness that their films would be most engaging if they could gain access to active processes—maintenance labor, construction, retrofitting projects—was challenged by the labor structures of our university system and my own lack of personal connections with facilities staff.

Moving into production, again the process of filmmaking gave students direct experiences with challenges of sustainability. Students filmed facilities crews picking up litter, gaining consent by agreeing not to show the workers’ faces. Another group filmed a campus greenhouse, struggling to make growing lettuces compelling documentary subjects. Students met with faculty in biology, environmental studies, and anthropology, experiencing the difficulties—and rewards—of producing compelling interviews. Students shared and discussed this work, developing their own perspectives on campus operations. The postproduction process reinforced these perspectives. Working on editing puzzles, discussing rough cuts, and ultimately screening the finished documentaries gave students valuable, shared experiences that will support more ambitious projects, including films, scholarship, and political organizing.

As mentioned above, the campus event by renewable energy skeptic Robert Bryce brought the broader context of these classroom experiences into relief. In his 2019 film, Juice: How Electricity Explains the World, Bryce—as producer, writer, and on-camera host—leads the audience through a series of scenarios emphasizing connections between electricity, quality of life, and power.[4] As the film’s press release explains, “The punchline of the film is simple: darkness kills human potential. Electricity nourishes it. Juice explains who has electricity, who’s getting it, and how developing countries all over the world are working to bring their people out of the dark and into the light.”[5] The film complements Bryce’s podcasting work, interviewing renewable energy skeptics, fossil fuel CEOs, and representatives of policy thinktanks to challenge potential transitions away from fossil fuels.[6] As Bryce summarizes, “The hard reality is that oil, coal, and natural gas are here to stay.”[7] The effectiveness of Bryce’s arguments lies in his move to link the individual and societal consequences of resource scarcity emphasized in Juice with the challenges of implementing large-scale renewable energy. Bryce argues that fossil fuel consumption is not only inevitable, but that reducing it will cause harm to the most vulnerable. The problematic assumptions of these arguments can be difficult to untangle for university students with little prior instruction in climate science.

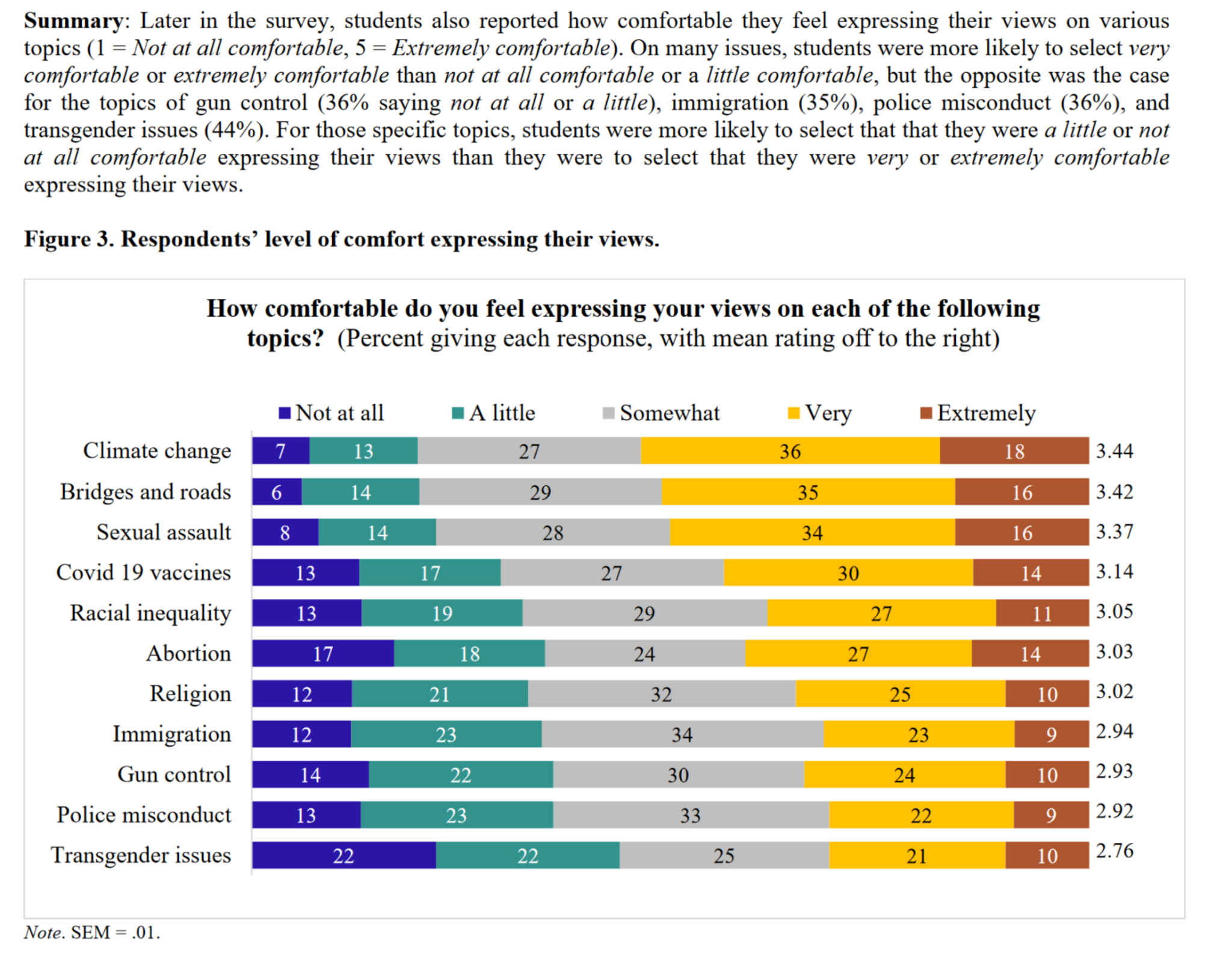

To help my students unpack these arguments, I investigated the broader context of the “Freedom of Expression” speaker series, which claims to better enable, “the marketplace of ideas to flourish.”[8] A key justification of this initiative is the recent system-wide survey of students, UW System Student Views on Freedom of Speech.[9] In this online survey only 54% of student respondents indicated that they were “very comfortable” or “extremely comfortable” discussing their opinions on climate change (see Figure 1).[10] Were the 46% of students uncomfortable expressing their views on climate change skeptical towards climate science, climate policy, and concepts of sustainability?[11] I fear that the intention of the speaker series is to use the University’s legitimacy to build a public in which skepticism towards climate science and renewable energy are valid positions, making space for the students the study implies are unable to freely express their views.[12]

While I disagree with the premise of this campus survey, it helpfully articulates the scale and scope of the work documentary pedagogy must perform to effectively counter speakers such as Bryce. The study challenges fundamental assumptions of much of my pedagogy: 1) students are able to learn about politicized subjects in the classroom; 2) students benefit from discussions of controversial topics; 3) instructors are capable of addressing a range of viewpoints in relation to course materials; 4) students’ critiques of course materials are a sign of engagement, rather than dismissal or danger. In their Introduction to Reclaiming the Popular Documentary, Christie Milliken and Steve F. Anderson frame these problems more broadly, “With regimes of knowledge increasingly fragmented and politicized for short-term gain, the stakes of documentary media and collective discourses of truth are higher—and more difficult to negotiate—than ever.”[13] Students’ documentary filmmaking experiences provide valuable resources for negotiating these challenges.

First, students must navigate the difficulties of film production, finding time in each other’s work and school schedules, transporting equipment, and coordinating postproduction workflows. This process produces invaluable situated knowledge about the film’s subject matter, filmmaking practices, and each other. Second, documentary filmmaking centers the ethical engagements between filmmakers and subjects, bringing considerations of “For whose benefit?” to bear on all relationships produced through the filmmaking process. Third, documentary filmmaking always includes elements of self-reflection, which can be teased out to examine the filmmakers’, classmates’, and instructor’s biases. Fourth, students become more cognizant of their own processes of focalization, better understanding how they see the world through the challenges of bringing an audience into their visions. These discussions of audience engagement—Who is this film for? Who is it not for? Why?—prompt us to think more precisely about the publics produced through their documentaries. In what ways do the institutional, departmental, and classroom contexts for these films impact the publics they produce? How do our institutional equipment policies, crew expectations, and postproduction workflows inflect these publics? By foregrounding the ways our courses, departments, and institutions shape the publics produced by our students’ films, we can begin to teach students to recognize the similar work performed by all films.

Emphasizing the publics produced through their films is also an effective way to help students parse problematic campus events. While I did not have the foresight to apply these methods of analysis to Bryce’s talk, in the future, I will be better prepared to critique campus speakers. By articulating the critical role of the production of publics to this speaker series, I can help my students remember to ask: For whose benefit? By understanding the publics produced by their films, students will more effectively grasp how campus events and system wide free-speech surveys perform analogous work in the production of specific publics.

Conclusion

These experiences prompt a reconsideration of the intersections between documentary publics and climate agency. As Jonathan Kahana argues, documentary filmmaking “engages the concept of publicness on all levels—conditions of production, textual structures, spaces and practices of circulation, contexts of reception . . . in such fraught and complex ways.”[14] Examining these layers of documentary films adds a critical—and easily overlooked—layer to environmental documentary pedagogy. As Kahana explains,

“the history of social documentary is impossible to imagine without the financial support of state, civic, and nonprofit agencies, foundations, societies, including unions, civil rights organizations, religious groups, political action committees, clubs, and so on. Such entities usually expect to generate cultural, political, or ideological, rather than financial, returns on their investment.”[15]

Academic institutions form another model of support, using equipment access, crew organization, postproduction facilities, and our own claims to students’ time to generate similar “returns on investment.”[16] What returns do we expect? How do our teaching methods accomplish these goals? Who benefits from these structures of documentary production? And specifically, in relation to climate agency: Is climate action—the presumptive goal of many environmental documentaries—supported by the publics we produce in our classrooms?

The entanglements between environmental documentary pedagogy and the publics it produces need to be further theorized. This analysis can support more effective implementations of place-based research, collaborative filmmaking, and ecological approaches to teaching media. Through these experiences students can effectively critique messaging by climate denialists and better understand the role of their own institutions, instructors, and cohorts in shaping campus discourse. Ultimately, making space for students to experience, share, and express the many challenges that face them is a critical step towards building publics capable of the action they think most necessary.

Adam Diller is an Assistant Professor of Radio, TV, and Film at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. He has exhibited internationally at venues including Anthology Film Archives, Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, Center on Contemporary Art. His scholarship has been published in journals including The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, Studies in Documentary Film, and Field Notes.

Nolan Swenson, “UWO Climate Event Sparks Concern,” Advance Titan, April 23, 2023, https://advancetitan.com/news/2023/04/19/uwo-climate-event-sparks-concern. ↑

To be clear, promoting sustainability is a central component of the University’s strategic plan. The University integrates teaching sustainability and climate change into its core curriculum. The tension is largely between the University and some local political actors, not within the University itself. ↑

Bremen Keasey, “Staff, faculty protest a proposal to outsource almost 100 UW-Oshkosh jobs to private company,” Oshkosh Northwestern, Sept 6, 2022, https://www.thenorthwestern.com/story/news/local/oshkosh/2022/09/06/uw-oshkosh-staff-march-against-plans-outsource-100-custodial-jobs/7905813001/. ↑

Tyson Culver, Juice: How Electricity Explains the World (2019; Austin, TX: Electric Elephant Films), https://youtu.be/heogFIjbwKY?si=yG76rpfZRWSiD5k3 ↑

“Press Kit,” Juice the Movie.com, accessed October 13, 2023, https://juicethemovie.com/press/. ↑

Robert Bryce, The Power Hungry Podcast, accessed October 13, 2023, https://robertbryce.com/power-hungry-podcast/. ↑

“Power Hungry,” Hachette Book Group, accessed October 13, 2023, https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/robert-bryce/power-hungry/9781586489533/. ↑

News Bureau, “UW System President Jay Rothman Announces Results of Free Speech Survey,” UW Oshkosh Today, February 2, 2023. https://uwosh.edu/today/112820/uw-system-president-jay-rothman-announces-results-of-free-speech-survey/. ↑

April Bleske-Rechek, Eric Giordano, Eric Kasper, Geoffrey Peterson, and Timothy Shiell, “UW System Student Views on Freedom of Speech,” Wisconsin Institute for Public Policy and Service, 2023. https://www.wisconsin.edu/civil-dialogue/download/SurveyReport20230201.pdf ↑

Bleske-Rechek et al., “Student Views.” ↑

The correlation between students expressing discomfort discussing climate change and conservative viewpoints is unclear. 7% of respondents chose “not at all,” 13% chose “a little,” and 26% chose “somewhat” to describe their comfort discussing climate change. My own experiences in classrooms on campus is that anything feared “too political” is challenging for all students to discuss openly. Bleske-Rechek et al., “Student Views,” 20-23. ↑

In later questions, the published study correlates students’ political viewpoints and their comfort expressing them. 67% of “very conservative and “somewhat conservative” students indicated that, “instructors often or extremely often create a climate in which students with unpopular views would feel uncomfortable sharing them.” Bleske-Rechek et al., “Student Views,” 58. Unfortunately, the survey does not correlate the question on climate change with political viewpoints, or distinguish between “on campus” and “in the classroom”—making analysis of the specific context of student’s responses to these questions difficult. ↑

Christie Milliken and Steve F. Anderson, eds., Reclaiming Popular Documentary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021), 1. ↑

Jonathan Milliken, Intelligence Work: The Politics of American Documentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008) 3. ↑

Milliken, Intelligence Work, 3. ↑

Milliken, Intelligence Work, 3. ↑