Navigating Bioregional Topographies in Documentary Film Production Pedagogy

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

For the past decade, I have taught undergraduate documentary production at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). Our campus is situated five minutes from the U.S.-Mexico border between El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, the sixth largest city in Mexico. The El Paso-Juarez bi-national metropolitan area has a population of 2.5 million and is the second-largest on the U.S.-Mexico border after San Diego-Tijuana. It is located in the Chihuahuan desert, the largest desert in North America and the most biodiverse in the Western Hemisphere. In reflecting upon my experience teaching in this unique part of the world, I observe powerful bioregional “ecologies of meaning” that have emerged in the context of student documentary production. The unit of the bioregion is useful for illuminating the way in which flora and fauna, geological features, and/or watersheds define the environmental and, by extension, cultural dimensions of a place.[1] UTEP falls in a bioregion that ranges from relatively contained Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature, to the much vaster North American Desert ecological region, as defined by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation.[2] Regardless of which label one chooses, UTEP sits in a desert ecosystem at the convergence of the Rio Grande watershed, the Franklin and Juarez mountain ranges, and the built infrastructure of a securitized border (See figure 1). Documentary students must navigate this topography in the course of their filmmaking, and these combined socio-ecological features suggest possibilities for rethinking documentary production pedagogy as inherently environmental in scope.

The process whereby my students come to their film topics involves a narrowing of focus that inevitably contributes to a deeper understanding of their surroundings, a kind of proto-bioregional awareness. The course I teach, Documentary Video Practicum, is comprised of around 25 advanced undergraduate students. The class centers on the production of 5-7 short documentaries by student crews assembled from the class. Feasibility and access ultimately determine the scope of the student films and arguably contribute to students’ connection to the sense of home or oikos intrinsic to the concept of ecology.[4] As the instructor, I probe the students regarding the premises and assumptions about the topic as well as the constraints of feasibility, i.e. what type of film can a group of 3-6 students with a full course load, part-time jobs, family obligations, and often complex transportation issues such as daily border crossings complete within 12 weeks? The range of topics I have seen over the years includes coverage of local art and music scenes, intimate portraits of elders and family members, profiles of young entrepreneurs, various aspects of youth culture such as skateboarding and gaming, films about filmmakers, and day-in-the-life stories of border-crossing students. Most productions take place on the El Paso side of the border given the logistical difficulties of going back and forth to Mexico, with the exception of the films explicitly about daily border crossings. By reverse engineering their films through the lens of feasibility and by thinking about their access to people, places, and happenings, eventually students settle on a sweet spot between specificity and timelessness that intersects with the circuits of their lives.

My students’ emergent sense of bioregional awareness through documentary filmmaking could be described as what Mares and Peña have called “autotopography,” a mapping of the self to the environment of the borderlands.[5] While Mares and Peña discuss such mapping in terms of explicitly “green” activities such as gardening, I argue that documentary filmmaking itself can serve as a “green” instrument of “autotopography.” The “cinematic footprint” of filmmaking, in Nadia Bozak’s terms, here becomes a literal index of one’s impact on the world.[6] In this way, documentary filmmaking begins to approach a bioregional form of indexicality through students’ incidental portrayal of regional natural and built environmental features in the background of any shot and, more specifically, in establishing shots and transitional sequences. An awareness of one’s bioregion through incidental filming of local environments, moreover, can potentially enable awareness of global climate change, much as regional efforts in conservation and restoration are viewed as the key to maintaining the Earth system in a sustainable post-Holocene state.[7]

The emergent bioregional awareness I see in my students is reflected in my own acclimatization to this largely high-altitude desert biome with a minority-majority population of Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano/a/x, and Latino/a/x denizens. The interactive way in which I help students generate their topics draws upon my own standing as a second-generation Pakistani-American “diasporic ally” with roots in the Detroit-Windsor bi-national metroplex, a northern counterpart to El Paso-Juarez and defined by the Detroit River.[8] The Detroit River is, in addition to an environmental feature, “a sedimentary accretion of stories and metaphors” about histories of resistance, such as abolition and the labor movement, as well as histories of oppression against the Anishinaabe and the ongoing disinvestment of the riverfront and the exposure of mostly black and brown riverfront denizens to environmental hazards.[9]

Since 9/11, that border, as defined by the river, has been increasingly securitized, a phenomenon my family and I have felt acutely on every border crossing from Canada back into the U.S. In contrast to border security on the southern border, which focuses on keeping out non-citizens, the operating principle of border agents on the northern border has been to sort U.S. citizens like our family, whose brown skin and Muslim names seem “out of place” despite the proximity of the largest diaspora population of Arabic speakers outside of the Middle East.[10] In many ways, like my students, I am familiar with the experience of being racialized by the border security apparatus and of living between two cultures as the child of immigrants to the U.S. There are however stark differences in the socio-ecological contexts of both borders due to both the difference in Border Patrol priorities and the affordances of the desert climate itself. On the Arizona-Mexico border, the Sonoran desert—an otherwise natural formation—has within the “spatial ideology” of U.S. Border Patrol become an instrument of deterrence against migrant crossings.[11] The built infrastructure of border crossings in turn discriminates between the lawful authority of Border Patrol and the potentially unlawful people waiting in line to cross in terms of the degree to which they are shaded from the sun.[12] Despite the stark difference in the way in which the desert climate is deployed as part of border security tactics and strategies on the southern border, the common experience I share with my students of being hailed as a racialized subject on the border animates the pedagogical dynamic in the class.

As a minority-identified instructor with a past on the corresponding northern border who presses her students to draw on their locales for the stories they tell onscreen, I am hailing students as border dwellers, and they are in turn often responding to that hail with emblems of the border. Both instructor and student are engaging in what Rey Chow terms “coercive mimeticism,” which entails “overlapping layers of projection, automatization, and self-ethnicization.”[13] Such an interaction involving the exchange of emblems risks students replicating dominant visual motifs of the border—“stereotypes” in Chow’s terms—including migrant river crossings and border patrol interactions. The constant presence—both clandestine and personified by border agents—of surveillance infrastructure in turn risks rendering any image making of the region an extension of surveillance, a “resource image” of border security in Nadia Bozak’s terms, that does not necessarily question the conditions in which it is made.[14] However, following Chow, I argue that this mimetic, realist documentary mode renders the relationship between self and the border environment in higher fidelity terms by acknowledging that stereotypes are a feature rather than a bug of cross-cultural—and I would argue cross-species, cross-kingdom, and living/non-living—visual encounters. Extending Rey Chow’s reading of the duplication of the “stereotype” as “always implicated in visuality” (66) and the intercultural point of contact being of necessity one of “(sur)faces,” I consider my students’ incidental filming of their environmental context as a kind of surface or background image as a starting point of bioregional awareness.[15] How students manage such images in their films transforms what could be initially interpreted as flat, stock imagery into a type of “border crossing,” in Chow’s terms, comprised of a “lethal confounding of cliché and creativity.”[16] If filming the environment in the context of documentary is a form of “autotopography,” then the encounter between self and border cliché or emblem may become a productive, creative space for students to explore the limits between self and other, and among the human, the more-than-human, and the inhuman.

In the borderlands, the most prominent and iconic environmental emblem in the popular imagination that is also a porous barrier between nations is the Rio Grande River, which in Mexico is known as the Rio Bravo. The Rio Bravo/Rio Grande is the basis for the Rio Grande watershed, which extends from southern Colorado to Brownsville, Texas in the U.S. and down to Chihuahua and Monterrey in Mexico. Many of the student films visually register the river indirectly through the natural and built environment that has accreted around it. The two mountain ranges in the area, the Franklins and the Sierra Juarez, sandwich the river from both sides of the border (See Figure 1). Since most film projects are set in El Paso, many students include as an establishing shot a wide angle image taken from the perspective of Scenic Drive, a lookout point in the Franklin Mountains which faces the Sierra Juarez range across the border (See figure 2). A mix of young adults and families gather here, the contrasting lures of shadowy make-out nooks and cheerful ice cream trucks beckoning the city. From this vantage point, depending on the time of day, the prominence of the river in the shot varies. By day, the cemented channel of the river fades into the continuous mass of the bi-national municipality of El Paso-Juarez. By night, the river channel pops in the shot as it is outlined with lights, and the shot takes on a chiaroscuro effect, with Juarez revealing its population density—nearly double that of El Paso—with its constellation of lights.

Common establishing shots such as this, which showcase the border security infrastructure against a dramatic natural backdrop approach a Romantic-era sense of what Margret Grebowicz has termed the “border sublime.”[18] Student films invoke this sublimity not merely as implied by the point of view of the camera but as made explicit by the gaze of the subjects in the frame. Such shots depict subjects contemplating the horizon, which, depending on the orientation of the shot, features either the Franklin mountains or the Sierra de Juarez range (See figures 3 and 4). These moments of contemplation, whether staged or spontaneous, indicate an awareness of and even reliance on elements in the landscape to turn inward as well as orient oneself in one’s world.

![Figure 3. Screenshot of closing shot of “En Busca de Rechazo [Looking for Rejection]” (Dir. Fernanda Ponce), in which the protagonist contemplates his personal journey in the film to overcome his fear of rejection while gazing upon the Franklin Mountains from the UTEP campus. Figure 3. Screenshot of closing shot of “En Busca de Rechazo [Looking for Rejection]” (Dir. Fernanda Ponce), in which the protagonist contemplates his personal journey in the film to overcome his fear of rejection while gazing upon the Franklin Mountains from the UTEP campus.](/j/jcms/images/18261332.0063.703-00000003.jpg)

Often that sense of orientation seems to omit the emblem of the border, the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo. Yet students often acknowledge the river by proxy by filming its surrounding scaffolding, which services interests in border security and trade, to set the scene for their autotopographical explorations (See figure 4). Such indirect shots of the river and its surrounding infrastructure depend on the fact that the part of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo that passes through El Paso is cemented and channeled as part of the resolution of the Chamizal dispute.[20] It is only when one ventures into southern New Mexico that the river bubbles into existence, a lively aspect of the river’s hydrological and political history that Mexican-American, Chicana, and Latina colleagues at UTEP, drawing on Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of “nepantla,” or “in-between-ness,” have described as one of “alluvial diffusion.”[21] The continued porousness of the river despite its having been paved over is underscored by the presence of layers of protest messages and graffiti on the Mexican side of the river (see figure 6).[22] The built environment around the river on the U.S.-side consists of the Interstate 10 Highway (I-10), a transcontinental freeway that extends from California to Florida. When the I-10 passes through El Paso, its curves vaguely echo the contours of the river, a feature that students often showcase in tracking shots taken from their cars. Students who commute from the eastside of El Paso to the westside to attend class often include such shots in their films to document their daily trajectories and in doing so also highlight the density of traffic through a region that serves as a cross-country corridor for imported goods from ports in Los Angeles and Mexico. In a film about border crossing, one student evokes the tedium of her commute with numerous repetitive point-of-view shots on the same freeway that cast a Sisyphean pall on her endless circuits between home and school.

Films that focus on students’ daily border crossings often use familiar shots of endless lines at checkpoints or point-of-view shots of a person crossing the pedestrian bridge by foot. The difference in framing between these views of the bridge implies a very different orientation of the subject in the literal space of the border. While the car line shots evoke the debilitating nature of urban life, with the mass of vehicles extending beyond the frame, the pedestrian bridge shots are much more contained, with the scaffolding of the walkway coinciding with the frames of the shot, creating a much more atomized experience of border life. One student artfully showed this contrast in a single shot that uses the bridge architecture itself to create a split-screen effect, drawing attention to the inherently fragmented nature of living one’s life across a natural and built border (See figure 5). In the same film, a point-of-view shot of the cemented channel showcases the graffiti that is scrawled with impunity on its banks (See figure 6). The shot continues to track backward, revealing that the shot was taken on the Mexican side of the pedestrian bridge and creating a vignetted effect using the architecture of the bridge itself. Taking the mundane setting of the director’s daily commute as a creative opportunity rather than limitation, the film begins to view the bridge itself as a frame—both a frame of reference and a cinematic frame—whose logic can be undercut and questioned through an aesthetic reorientation. Though such images initially show a reliance on stock representations of the border region, they are indicative in part of the cross-cultural exchange defining the pedagogical space of the class, which in turn sets the stage for students to begin to question the visual emblems associated with their built and natural environments.

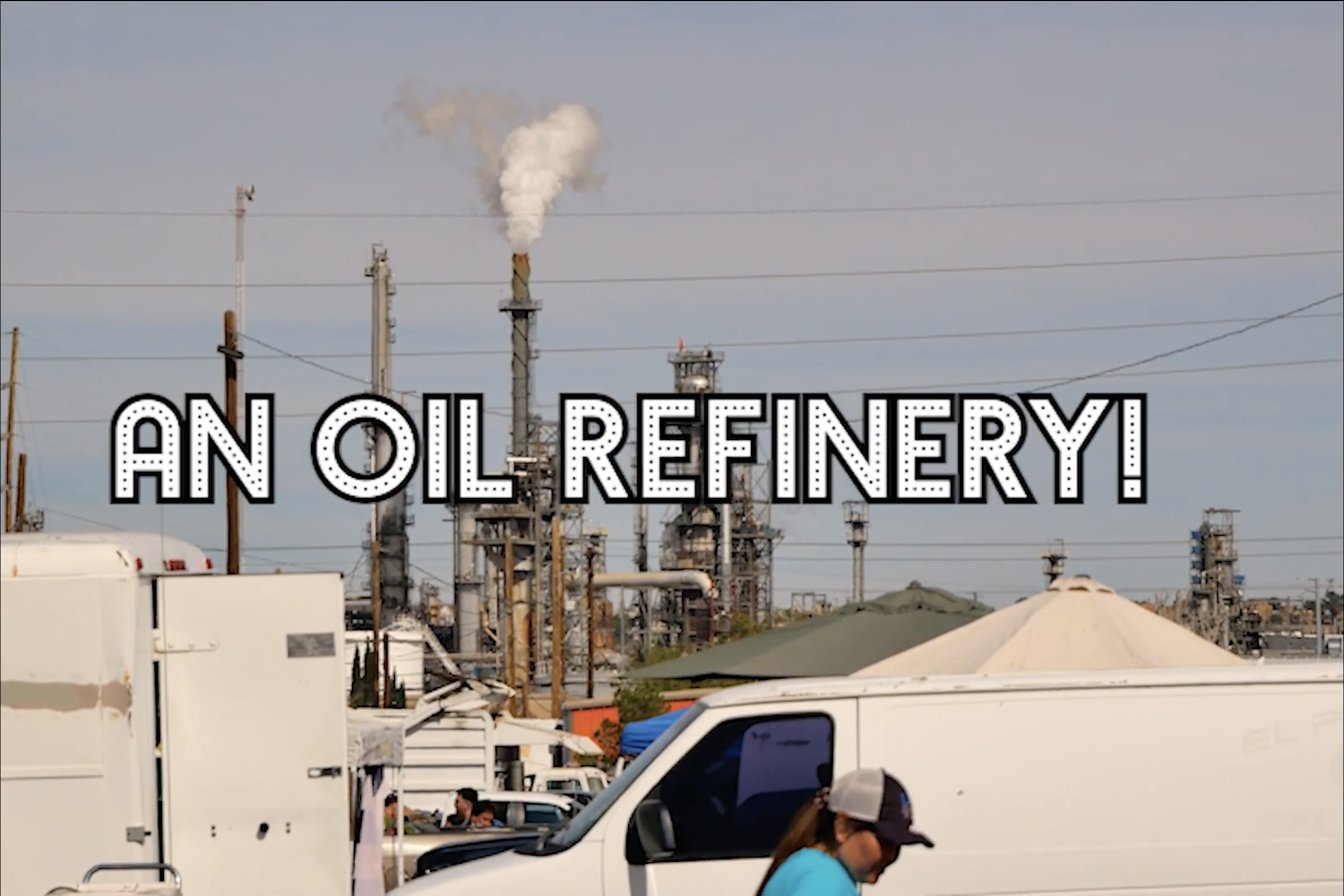

As I continue to work with students in this context, I see important opportunities for urging self-reflection about how they film landscapes and cityscapes of our local surroundings. In future iterations of this class, I hope to encourage students to collectively define existing emblems of the border region and to imagine ways of retooling them so that the stock and the stereotypical brim with life. That focus on life and liveliness in turn would translate into an explicit engagement with the desert bioregion and ecosystem as subject. In a film from a recent class, one student brings the background to the foreground by drawing attention through on-screen text to the looming presence of an oil refinery in many of the shots of his film, which depicts a popular flea market that is also close to the largest public-use recreational park in El Paso County (See figure 7). This film anticipates the viewer’s curiosity about the incongruity between human activity and oil infrastructure in a humorous way and also speaks to the filmmaker’s heightened awareness and concerns about environmental exposure.

A focus on students’ surroundings as a subject of media also warrants looking at those environs as a media practice. Janet Walker’s “media mapping” approach could be used to account for the ways in which the border regions of the Desert Southwest of the United States have figured and been figured by media across genre and platform alternately as a filming location for racist and anthropocentric narratives, as an index and prognosticator of climate extremes, and as a carceral zone of surveillance.[26] The debates in defining bioregions that I referenced at the beginning of this essay show that they are “necessarily also cultural zones that are contested and negotiated” as well as “part of global processes that would occur with or without the presence of humans.”[27] To that end, I would also encourage students to consider the geological scale of the Rio Grande watershed, undergirded as it is by the Rio Grande Rift, which follows the river from Colorado to Chihuahua, Mexico. The recent discovery of fossilized human footprints in nearby White Sands National Park dating to about 23,000-21,000 years ago—the oldest documented human presence in North America—in turn warrants attention to the ways in which ancient ecosystems and cultures may have shaped current natural and cultural forms.[28] In sum, the student films that I have screened over the past decade of teaching documentary film production in the borderland bioregion indicate students’ attunement to their environments, their emergent recognition of borderland bioregional “ecologies of meaning” and their corresponding development of an audiovisual topographical grammar that can be adapted to documentary production classes in any locale.

Sabiha A. Khan is an Associate Professor of Communication at the University of Texas as El Paso. Her research and creative work focus on food, environment, and culture in documentary media, animation, and food systems communication. Her research has been published in Feminist Media Histories, Media + Environment, Food and Foodways, Frontiers in Science and Environmental Communication, and other venues.

John Charles Ryan, “Humanity’s Bioregional Places: Linking Space, Aesthetics, and the Ethics of Reinhabitation,” Humanities 1, no. 1 (2012): 80-103, doi: 10.3390/h1010080. ↑

“Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World,” World Wildlife.org, accessed December 31, 2023, https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/terrestrial-ecoregions-of-the-world; Commission for Environmental Cooperation, “Ecological Regions of North America,” accessed December 31, 2023, https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america. ↑

Earth from Space Collection, International Space Station and JSC Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center, accessed December 31, 2023, https://eol.jsc.nasa.gov. ↑

J. M. Meyer, Political Nature: Environmentalism and the Interpretation of Western Thought (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2001). ↑

Teresa M. Mares and Devon G. Peña, “Environmental and Food Justice: Toward Local, Slow, and Deep Food Systems,” in Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability, eds. Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2011), 197-219. ↑

Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012). ↑

Eric Dinerstein et al., “An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm,” BioScience 67, no. 6 (June 2017): 534-45, doi: 10.1093/biosci/bix014. ↑

Sabiha Ahmad Khan, “Cultivating Borderland Food Memories, from Field to Screen,” Food and Foodways 24, no. 1-2 (2016): 92, doi: 10.1080/07409710.2016.1150098. ↑

David Porter, “The Detroit River Story Lab: Community Narratives and Ecosystems in Great Lakes Research,” Journal of Great Lakes Research 48, no. 6 (December 2022): 1485-88, doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2022.05.018. ↑

Geoffrey A. Boyce, “Appearing ‘Out of Place’: Automobility and the Everyday Policing of Threat and Suspicion on the U.S./Canada Frontier,” Political Geography 64 (May 2018): 1-12, doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.001. ↑

Haeden Stewart et al., “Surveilling Surveillance: Countermapping Undocumented Migration in the USA-Mexico Borderlands,” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3 no. 2 (2016): 161. doi: 10.1558/jca.31761. ↑

Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller, “An Ultraviole(n)t Border,” e-flux Architecture (April 29, 2020), accessed November 12, 2023, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/at-the-border/325756/an-ultraviole-n-t-border/. ↑

Rey Chow, The Protestant Ethnic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 107, 126. ↑

Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 2. ↑

Chow, Protestant Ethnic, 66. ↑

Chow, Protestant Ethnic, 81. ↑

Omar Garcia, “History of Food Trucks, El Paso, TX,” Student film, Department of Communication, The University of Texas at El Paso, 2023. ↑

Margret Grebowicz, "The Border Sublime,” Public lecture at Galeria 17, Pristina, Kosovo, May 17, 2023, accessed December 31, 2023, https://galeria17.org/en/public-lecture-the-border-sublime/. ↑

Fernanda Ponce, “En Busca del Rechazo [Looking for Rejection],” Student Film, Department of Communication, The University of Texas at El Paso, 2023. ↑

Carlos Tarin, Sarah Upton, and Stacey K. Sowards, “Borderland Ecocultural Identities,” in Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity, eds. Tema Milstein and José Castro-Sotomayor (New York: Routledge, 2020), 57. ↑

Tarin et al., “Borderland Ecocultural Identities,” 54. ↑

Tarin et al., “Borderland Ecocultural Identities,” 59. ↑

Eugenio Cantu, “Haunting the Truth,” Student film, Department of Communication, The University of Texas at El Paso, 2022. ↑

Kimberly Chavez, “The Border,” Student film, Department of Communication, The University of Texas at El Paso, 2022. ↑

Yudah Diaz, “Ascarate Boogie,” Student film, Department of Communication, The University of Texas at El Paso, 2022. ↑

Janet Walker, “Media Mapping and Oil Extraction: A Louisiana Story,” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies 7, no. 2 (2018): 229-251, doi: 10.25969/MEDIAREP/3448. ↑

Bron Taylor, “Bioregionalism: An Ethics of Loyalty to Landscapes,” Landscape Journal 19, no. 1-2 (2000): 62, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43324333; Dianne Meredith, “The Bioregion as a Communitarian Micro-region (and Its Limitations),” Ethics, Place & Environment 8, no. 1 (2005): 88, doi:10.1080/13668790500115755. ↑

Matthew R. Bennett et al., “Evidence of Humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum,” Science 373 (2021): 1528-1531, doi:10.1126/science.abg7586. ↑