Stardom, Cinephilia, and the Affective Contours of Bollywood’s Soft Power in China

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

Abstract: Given multiple wars and border skirmishes, the India-China relationship has been defined through a lens of conflict with little attention paid to the potential affinities between the two. This article examines the stardom of Aamir Khan in China as an instantiation of stardom, cinematic affect, and audience agency that reveals deep-seated cultural resonances and affinities. Analyzing user comments about Khan on Chinese social media platforms Douban and Mtime, this article explicates the affective underpinnings of Khan’s soft power. It illustrates how soft power through individual social actors can exist outside of state-centric media and exceed the boundaries of the nation-state.

At the height of a border skirmish between India and China in 2017 over the disputed territory of Doklam, claimed by Bhutan and supported by India, Bollywood megastar Aamir Khan’s film Dangal (Nitesh Tiwari, 2016) became a means to de-escalate tensions brewing on the Sino-Indian border. India’s and China’s perceptions and policies vis-à-vis one another have historically been adversarial. Given the two countries’ tenuous bilateral relationship—including tensions over Indian asylum to the Dalai Lama and displaced Tibetans as well as three Indo-China wars that haunt their relationship—the Doklam border dispute was a combustible situation. During this fraught diplomatic moment, however, China’s envoy to India, Sun Weidong, turned to Indian star Aamir Khan and Bollywood, repeatedly emphasizing Chinese premier Xi Jinping’s admiration for Khan and describing Xi as the “biggest promoter of Bollywood in China.”[1] In a meeting that followed, Xi professed his appreciation for Dangal yet again, this time directly to the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi (2014–). Thus, Dangal became an affective anchor for the dissolution of tension between the two countries. In his press briefing, Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar trumpeted Xi’s cinematic approval, which Modi proudly reaffirmed in an election rally in the Indian state of Haryana, the setting for Dangal: “China’s President told me . . . with a lot of pride, that he had watched the movie Dangal, and he said, ‘your daughters are amazing—I have watched the full movie.’ As I was hearing this from China’s President . . . I was feeling pride for my state of Haryana and the power of this state.”[2]

The case of Aamir Khan and his popularity in China articulates a distinct theoretical understanding of cinematic soft power. It combines the concept of soft power with ideas of stardom, the affective pull of cinephilia, and audience agency that conjunctively work together beyond state-centric cultivated “attractions” through media that paint the nation in a positive light for foreign publics.[3] Joseph Nye, who coined the term soft power in 1990, defined it as the ability to affect others (nations and their citizens) by attraction and persuasion rather than coercion and payment.[4] This power was in stark contrast to hard military power. Media and entertainment became crucial to creating this type of attraction. However, earlier conceptualizations of soft power were based on the understanding that state-centric discourses often instigated these attractions. Nye mentions soft power as an intangible aspect of power that states avail themselves of through interdependent global economic transactions that facilitate cultural exchange and attraction. While this power is intangible, in the American context that Nye elaborates, it remains state-centric. The American state instigated and facilitated the cultural and media flows that generated such attractions. For instance, having realized the power of TV, President John F. Kennedy facilitated the sale of Hollywood-produced TV and film content around the world as a natural extension of US economic interests and as a way to increase exports. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) chair Newton Minow campaigned with the industry to link public interest in broadcasting with the national interest in foreign affairs.[5]

The case of Aamir Khan reveals an alternative framework for soft power that is neither hegemonic nor state-centric but marshaled by individuals operating within industry-driven frameworks. This affective soft power is “rooted in the political dynamics of emotion” and is derived from an audience’s affective investment in produced images.[6] Stars and their fandoms, mediated through technology and social media, offer a new understanding of influence that can operate outside of state-centric discourses. The attentiveness to audience agency and its centrality in this process becomes even more pertinent because Chinese state censorship limits liberal-minded urban Chinese voices.[7] This article foregrounds the “deep-seated underpinnings” of soft power that lie in affect.[8] “Affective investment . . . [is the] conceptual anchor . . . of soft power,” which Ulrich Beck calls a hazy power space where power is transformed into national influence but not easily quantifiable.[9] Sociologist Peter M. Hall adds that soft power is a form of meta-power, a complex set of relationships and social action where individual actors are critical to the dynamic and present new possibilities and orientations.[10]

Khan’s soft power is unique, existing outside of state-centric media and at the boundaries of nationality. His affective pull and positioning in an industry-centric discourse lend him a hybridity that makes him instrumental to the tenuous Sino-Indian diplomatic relationship. He emerges as an anchor who can connect with Chinese audiences through resonant core values stemming from parallel modernities and Eastern thought reflected in Khan’s on- and off-screen personas. Within this framing, Khan’s appeal in China reveals lateral media flows among neighboring Asian states, shifting the focus away from dominant Western/Anglo-centric discourses about media flows and cultural influence.[11] To this earlier articulation of imperialism and state ideologies through media flows, this article incorporates a unique instantiation of stardom, cinematic affect, and audience agency, which reveal moments of power or fissures wherein audiences, the star, and industrial nodes possess agency beyond the nation-state. These fissures and moments of agency signify an industry-oriented dynamic anchored in individual social actors, not the nation-state. This article thus contributes to a novel understanding of stardom and cinema’s affective power within debates about global media flows, cultural diplomacy, and new cinephilic discourses.[12]

Following the onset of new digital technologies in the 1990s, cinephilia that focused on the aura of cinema and a certain way of loving and consuming eclectic films was proclaimed dead, although there were continuities and ruptures in the way new cinephilia revised and renewed the strategies of cinephilia. The proponents of new cinephilia questioned the anguished requiems of cinematic loss, insisting that the “philia” was gustier and more intense in digital spaces.[13] The fact that “one can (legally or often illegally) download copies of films from peer-to-peer systems or exchange DVDs or tapes with other cinephiles on the internet” showed a more intense attraction.[14] Scholars further emphasized that old cinephilia was Euro-centric and privileged white, male, heterosexual identities while seemingly constructing an illusion of wholeness.[15] This article furthers the democratizing discourse of new cinephilia by moving away from hierarchical ideas of accessing cinema. Instead, it explores geo-politically lateral cinematic ties that center access that started with pirate cinema flows through the kinds of digital spaces scholars such as Mellis Behlil argue for.[16] In centering affect, beyond the mechanics of form and ritualized consumption, in the discourse of cinephilia, this article participates in the generative and democratized notion of new cinephilia. It also reasserts parallel modernities and value proximities that delineate lateral media flows amid two of the world’s most populous and influential, albeit politically divergent, Asian economies.[17]

Methodologically, this study analyzes audience comments and blog posts about Aamir Khan’s films on the popular Chinese social media platforms Douban and Mtime.[18] It takes up Goubin Yang’s and Shiwen Wu’s exhortations to resuscitate and foreground narratives of affect in Chinese digital spaces and combines it with new cinephilia, especially in the context of the now inaccessible website Mtime, documenting the active and activist in these alternative audience points of view.[19] The audiences challenge perceived wisdom about the perception of India through the lens of Khan and his films. The analysis interweaves a discursive understanding of Sino-Indian historical ties, of the cinematic exchange between the two countries, and of the construction of Khan’s stardom in China based on archival and journalistic sources such as the Times of India, South China Morning Post, the National Archive of India, and other databases. The audience analysis is based on comments posted on Douban and Mtime about Khan’s films 3 Idiots (Rajkumar Hirani, 2009), PK (Rajkumar Hirani, 2014), and Dangal and his TV show Satyamev Jayate (Truth Alone Triumphs, STAR India Network, 2012–2014). My methodology thus brings together archival work that illuminates geopolitical exchange with audience analysis and discursively combines it with theories of new cinephilia and soft power. In so doing, this article posits an alternate affective framework to understand cultural attractions and diplomacy that recognizes audience agency and the role of individual non-state actors such as Khan in this process.

Khan’s film Dangal was a feel-good sports film based on the real-life story of two women wrestlers from the Indian state of Haryana who, against societal expectations, are encouraged by their father to take up wrestling and eventually earn India international laurels. The political potential of Dangal, however, was not completely accidental. This moment of possibility and mediation was instigated by Aamir Khan’s (the protagonist and producer of Dangal) adventitious stardom in China. His film 3 Idiots, the story of three engineering students navigating India’s competitive education system, had made its way to China through piracy networks. The immense success of 3 Idiots in China came as a surprise to Khan and the producers of the film, who perceived its popularity as an accident: “When I got to know, and the director got to know that our film is very popular in China, we were like, but it is not released over there.”[20] It was unexpectedly hailed as a classic.[21] Douban lists 3 Idiots and Dangal among the top foreign films of all time (see Figure 1).

Through social networks such as Douban, Mtime, and Weibo, Khan enjoys cult stardom in China; he boasts 1.4 million Weibo followers.[22] Dubbing him their favorite uncle, Chinese youth celebrate his socially conscious star persona and willingness to create cinema that “makes a difference.”[23] While Khan and his films found a dedicated following in China starting in 2010, when 3 Idiots found its way to the country through Hong Kong pirate networks, it was Dangal that prompted both the Indian and Chinese states to leverage the happenstance of Khan’s stardom to allay an escalating conflict. These developments were noteworthy in the context of the Sino-Indian relationship, which has broadly been defined by and constructed through a lens of conflict, with little attention paid to the cultural ties and potential affinities cultivated through cinema, stars, or their fandoms.[24] Unsurprisingly, China hailed India’s proposal to appoint Khan as a brand ambassador to boost trade between the two countries.[25] China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying responded to the announcement by saying, “Aamir Khan is a very famous Indian actor [in China]. Many Chinese, including myself, have watched [Khan’s] movie Dangal. . . . Watching Bollywood movies [is] becoming a new fashion among young Chinese people.”[26] Within this space, Khan became the Chinese state’s exceptional Indian.[27] Official, state-regulated social media narratives framed Khan as too good to be Indian, a celebrity anomaly that Indians do not care much about. Through articles on Sohu and Baidu, Chinese officials apparently hoped to mitigate a Khan-inspired cultural attraction to India by detaching the values Khan represents from the nation he represents.[28] This exceptional narrative positioned Khan as a nation-less or nation-neutral celebrity, made possible by the historical evolution of Bollywood, which lacked Indian state recognition until 2001.[29]

In contrast to the Chinese state perspective that focused on diminishing Khan’s Indianness in the wake of his burgeoning popularity, the Indian state has, since Doklam, sought to marshal Khan’s affective resonance in China. The Indian approach is premised on the idea that films set in India featuring a star the Chinese people like can show the attractiveness of the Indian nation, its culture, and its people. However, this attempt at cinematic and celebrity diplomacy is new and can be framed within the larger happenstance of Khan’s Chinese stardom. When Prime Minister Modi’s visit to China unexpectedly aligned with Khan’s film promotions for PK, Khan insisted it was a coincidence.[30] Nevertheless, this fortuitous circumstance marked the coalescence of Khan’s stardom with India’s improvisational soft power strategy. Following the visit, aware of the burgeoning cinematic network and affect anchored through Khan, the two states signed a memorandum that sought to address their enormous trade deficit through film collaborations.[31]

In the absence of a deliberate state soft power strategy, attentiveness to audience agency and its centrality in this process becomes pertinent because Chinese state censorship limits liberal-minded voices. Goubin Yang and Shiwen Wu assert that the history of the Chinese web is one of contention, dissent, and containment. Chinese netizens have been creatively fighting censorship to assert their opinions and agency on Douban, Mtime, and similar platforms recently under intense state scrutiny.[32] Douban—a popular platform in China for expressing opinions and sharing experiences, reviews, and film and entertainment recommendations—has been at the receiving end of political crackdowns against “extremism and radical politics,” including the cancellation of its feminist channels.[33] A significant portion of Douban’s user-generated content is about films. Like IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes and functionally comparable to Twitter, it is a follower network wherein users can broadcast messages. Mtime.com was a movie marketing platform headquartered in Beijing that Mtime CEO Kevin Hou described as a combination of Rotten Tomatoes, IMDb, and Fandango.[34] It provided branded movie reviews aggregated from users and in-house editors. Mtime.com is no longer available to users, reflecting the phenomenon of disappearing websites in China as a way to control and curb dissent.[35]

Douban and Mtime users are mainly middle-class, urban youth and white-collar workers who read books, listen to music, and watch movies.[36] A focus on the comments of these users, especially as it pertains to Khan and his films, brings an audience and cultural studies lens to the discussion of soft power attractions and cultural policy, especially in the context of China, a state heavily invested in creating influence through state-sponsored media industries such as CCTV International.[37] This article thus shifts the focus to audience agency and its ability to effect change. This change, outside of state orchestration but mediated through pirate economies and social media networks, becomes an empowering anomaly that recognizes that audiences can forge an alternative understanding of cultural attractions and power through individual social actors—stars such as Aamir Khan. The following sections first situate the history of Sino-Indian cinematic ties in the broader geopolitical context of the two countries followed by a discursive analysis of Khan’s stardom in China that found a gradual footing starting with the unexpected success of 3 Idiots and culminating in Dangal.

Before there was Hollywood in China, there was Bollywood. It was [Awaara] that first gave millions of Chinese a window on the outside world—a world that was not about ideology or revolution but about the pursuit of freedom, love, and humanity.

—Haiyan Wang[38]

India established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China on April 1, 1950, the first non-communist/socialist nation in Asia to do so.[39] Their first exchange happened soon after, on April 27, 1952, with Vijaylakshmi Pandit, an Indian diplomat and politician, leading India’s cultural and goodwill mission to China. The visit produced a quandary, as Pandit noted: “Chinese officials had expressed a strong and repeated desire to see a full-length feature film depicting Indian social and economic conditions.”[40]The newly instituted Indian government derided popular cinema. Film critic Aruna Vasudev opines that until 1951 popular cinema was “treated at worst as a reprehensible, though unavoidable, social catastrophe, at best a barbarous pastime for the uncultured.”[41] Therefore, officials scrambled to find what would be a suitable film. Indian and Chinese state attitudes toward films were deeply divergent. James D. Decker and Patrick S. Brennan note that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the Maoist era deployed films as an Althusserian ideological state apparatus. For the CCP, films were a way of educating, indoctrinating, and creating political myths through cinematic symbolism.[42] Hence, the Chinese state insisted on understanding the newly independent India through cinema. Indian officials, despite their disdain for mainstream popular cinema, eventually selected two movies, the Hindi film Awaara (Raj Kapoor, 1951), in which famous Bollywood star Raj Kapoor plays an affable vagabond wronged by society, and director V. Shantaram’s Amar Bhoopali (1951), a Marathi film about a cow herder with the gift of poetry.

However, the cultural exchange and bonhomie between the two countries did not last long. The Sino-Indian Wars of 1962 and 1967 soon followed. Around the same time, the Cultural Revolution in China ensued, a decade of political and social chaos marked by unfathomable brutality. The Chinese were consumed by events closer to home. In the subsequent decades, there was little to no cultural exchange between the two nations.[43] Nevertheless, Haiyan Wang notes that to Chinese people born in the 1960s, the songs from Awaara were the coolest, trendiest thing.[44] Awaara’s socialist underpinnings reflected on the individual in society. The evocation of the nature versus nurture debate, the centrality of the parent-child relationship, and resonances with the Chinese tradition of the “chaste” widow struck a chord with the audience.[45] Awaara’s reception, however, Nitin Govil asserts, had a mixed, contradictory diplomatic history. Based on state objectives, the film was hailed either as Mao’s favorite film, a “symbol of state camaraderie,” or a film whose music was corrupting Chinese society.[46]

After the Cultural Revolution, Indo-Chinese cultural ties were renewed again with a cinematic exchange led by Awaara, which screened in cinemas in 1977. Wang notes, “[The film was] a breathtaking experience for millions of Chinese people. The people were blown away by the songs, sensuality, and the artistry, imagery, and radiant beauty” of the main characters—Hindi cinema’s iconic stars—Raj Kapoor and Nargis: “For the first time, watching a movie was not about getting a lesson in communism but about letting your imagination run.”[47] The exchange, though fleeting, was also significant from a cultural and geopolitical perspective. Krista Van Fleit observes that the presence of Indian films in China allowed for “a different form of knowledge,” one that “perhaps [brought China] a step forward towards shrugging off the reliance on the west as a point of comparison.”[48] The 1970s saw a few other releases such as Karwaan (Caravan, Nasir Hussain, 1971) become popular through theatrical releases. Produced by Tahir Hussain, Aamir Khan’s father, the film succeeded and serendipitously foreshadowed Aamir Khan’s popularity in China decades later. An Indian national policy document published in 1976 reveals that India felt compelled to improve its ties with China due to the shifting geopolitical power dynamic in the wake of the US defeat in Vietnam. The document states, “the historic defeat of the US policy of intervention in Indo-China, marked by fall of regimes propped up by the US in Saigon and Phnom Penh, the situation in Southeast Asia remains rather fluid.”[49] In this context, Karwaan got a Chinese release, in 1979. However, due to the vagaries of Sino-Indian ties and following another border skirmish in 1987, the Sumdorong Chu Standoff, the import of Indian movies to China dwindled, with only about thirty Indian films screened in China between 1980 and 1999.[50] After this decades-long hiatus, Aamir Khan’s Oscar-nominated Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India (The Tax, Ashutosh Gowariker, 2001) got a Chinese release in November 2002. Lagaan was the first Indian film released nationwide in China as a revenue-sharing title. Although one of twenty films that made that year’s limited quota of foreign revenue-sharing films allowed by China, Lagaan did not generate an overwhelmingly positive response.[51] Its runtime was seen as an impediment.[52] However, the love of Hindi cinema however reignited in the following decade when Khan’s 3 Idiots arrived in China through piracy networks.

Aamir Khan’s 3 Idiots proved to be a landmark film for Bollywood’s flows to lateral markets. Chinese audiences gave it an overwhelmingly enthusiastic reception, the first Bollywood film since Awaara to garner such a response. It is listed on Douban as a foreign classic alongside Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, 1994) and Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) and has more than 1.5 million ratings on the website.[53] A blockbuster hit, 3 Idiots collected US$90 million at the box office worldwide.[54]

China at the time was almost an afterthought in the global film business, only the fifteenth largest market in the world, with aggregate national box office revenue below that of South Korea, Canada, and Australia.[55] Arriving via Hong Kong, a media capital between the East and West, between capitalism and totalitarianism, and a conduit for the film, 3 Idiots enabled a lateral industrial flow and instigated a cult fandom for Khan. It was first screened at the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 2010, garnering word-of-mouth publicity that led to a Beijing International Film Festival screening.[56] Circulation through informal piracy networks finally culminated in a theatrical release by Reliance Entertainment Corporation, a globally networked Indian media company that had gained international stature by bailing out Hollywood’s DreamWorks in 2008.[57] Reliance released 3 Idiots with 342 overseas prints circulating in forty countries, making it the most significant domestic and worldwide release for a Hindi film until then.[58]

Beyond the acclaim of its star and the visibility garnered by the film because of its wide release across the globe—something that had hitherto been impossible for any Bollywood film—the film’s technological mediation through sites like Douban and Mtime was critical in initiating and perpetuating a cult following for the film and for Khan. Situating this perspective of digital fan/user mediations foregrounds the non-state-centric cultural influence triggered by Khan and his films that later became crucial to Sino-Indian geopolitics. Networked piracy provided the infrastructure for the circulation of Bollywood films in China in a way that decentered traditional understandings of soft power and how it operates. As Brian Larkin notes, legitimate media forms sometimes cannot exist without the infrastructure created by its illegitimate double pirate media.[59] Larkin’s argument extends to Bollywood’s legitimate presence, cult fandom, and cultural influence in China that could not have existed without the early piracy infrastructure that led to 3 Idiots’ and Khan’s cult success.

India and China’s tenuous political relationship has been marked by chaotic uncertainty. Consequently, the possibility of an affective dialectic of cultural understanding had to emanate from outside state discourse, through cinephilic exchange. I explicate the audiences’ primary terms of engagement with 3 Idiots and analyze how the engagement was replicated and strengthened through Khan’s star persona and led to comparative imaginaries of India and China. Shared values reflected in Indian socio-cultural realities and structural, institutional, and economic shortcomings common in both countries, such as a hyper competitive education system, lack of infrastructure, and a rural-urban divide, resonated with the audiences because they faced similar challenges. These imaginaries, in turn, created an attraction or soft power initiated through an individual social actor, that is, Khan, rather than the state and countered state-driven perceptions about India.

The initial attraction for 3 Idiots was due to its resonant plot that tackled the Indian education system. The plot revolves around three students at an elite engineering college in India. Their friendship, romances, and escapades provide the story’s humor. Despite the film’s lighthearted comedic mode, it is a scathing critique of India’s educational system. Based on the novel Five Point Someone by Chetan Bhagat, an alumnus of India’s highest-ranked engineering college, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), 3 Idiots reveals the harsh, unrelenting pressure of Indian education. The movie’s fictitious Imperial College of Engineering parodies the coveted, highly competitive IITs. The desire to get into these institutes “has spawned a $3.4 billion venture capital-backed coaching industry, inspired millions of Indian teenagers to forgo partying, socializing, and sleep in pursuit of their studies, and caused an annual media craze that consumes the country.”[60] Students use Ivy League schools as their safety schools because getting into an IIT is much harder.[61]

Through Rancho, the character played by Khan, the film critiques the Indian education system. It highlights the perils of unhealthy competition, focalizing a lack of educator empathy that creates high-pressure, stressful atmospheres that drive students to mental health disorders or suicide.[62] The film likewise criticizes the emphasis on rote learning. Throughout the film, Rancho insists on learning that encourages innovation and experimentation rather than regurgitating textbook facts. It is a not-so-veiled critique of the Indian middle-class ethos that privileges specific kinds of knowledge that prioritize earnings over learning. On a more nationalistic note, the film also cynically comments on brain drain. IIT institutes are government-run academic institutions funded by taxpayer money and focused on providing exemplary education to the students who can get through the competitive system. However, most graduates aspire to lives of wealth in the United States or other first world countries rather than giving back to the institute or India.

Audience reception of 3 Idiots predominantly centered on the themes of education, the film’s distinctive Bollywood aesthetic, and cultural and political comparisons between India and China. The critique of the education system resonated with many viewers. A blogger and commenter on Mtime stated, “the reason why 3 Idiots resonates strongly with the audience is probably because the reality reflected in the film is so like the current reality in China. Therefore, even though the film is full of exotic colors, the audience can understand the connotations and [perceive] the issues as interlinked.”[63] Another viewer noted, “not watching this film would be the mistake of your life. 3 Idiots is a good movie that defies authority and challenges dogma. It awakens our most authentic nature and tells us what we should pursue. Especially when you are relatively young, especially when you still have time to resist, then try to resist. As the person in the film said, you don’t have to learn for money and status, learn for your interests and hobbies, and follow your heart.”[64]

Fans noted the similarities between the Indian and Chinese education systems and were visibly moved by the dire pathos of events depicted in 3 Idiots. One fan argued that the film “reflects . . . the dearth of quality education resources in India, which has a great deal of similarity with China’s College Entrance Examination [Gaokao] system and that of other neighboring Asian countries.”[65] Another commenter reflected on the socio-cultural resonances noting, “I can sense the similarities in social issues about the education system and the wealth gap that China and India face, and thus I feel a strong sense of resonance with the movie.”[66] Delivered in an optimistic and enjoyable Bollywood masala genre, the film depicts, according to another Chinese fan, a “seemingly joyous college life” that does not preclude “incidents of suicide of students overwhelmed by stress. Students in mainland China cannot be more familiar with all of this.”[67] Several comments discussed the film’s lack of dogma, making fans think about the purpose and meaning of life and education and reflecting on the reality Indians and Chinese share. Aamir Khan as the star of 3 Idiots thus discursively came to embody the shared values that both Indian and Chinese cultures aspired toward.

In situating the centrality of affect in reception studies, Janet Staiger argues that how a text intersects with culture and how the recipient culture evaluates those emotions are critical to reception.[68] Linking affect to the political, Staiger, Ann Cvetkovich, and Ann Reynolds note that “perhaps we truly encounter the political when we feel” and that an ideological critique of the public sphere can be perceived through the lens of individual emotion and social rhetoric resonating within it.[69] Staiger’s exhortation for a “socially constituted politics of affect” in conjunction with value proximities that accentuate the affect created by Hindi cinema’s narratives and stars explains the reception of Indian cinema in China.[70]

Khan’s films 3 Idiots, Dangal, PK, and Taare Zameen Par (2007) consistently evoked mutually resonant values in Confucianism and Indian cultural and philosophical thought. Resonances that stem from shared Eastern philosophies that reflect upon notions of individualism versus collectivism, national growth, and similar development concerns in two of the world’s most populous countries. Confucianism emphasizes hierarchy, order, and the relational value placed on loyalty and harmony within a paternalistic leadership framework.[71] These ideas resemble those in the Bhagavad Gita that delineate the individual’s situation in society and emphasize the need to rise above individual desires and serve the cause of spiritual humanism.[72] Eastern thought thus values the social collective over the individual and, in this context, becomes a conduit for audience engagement and affect.

The idea of education is touched upon in several of Khan’s movies but most prominently in 3 Idiots, Khan’s gateway into China. The basic tenets that define a Confucian scholar are essence of the human being that manifests as compassion (ren), righteousness (yi), propriety (li), filial piety (xiao), and loyalty (zhong) to one’s ruler that leads to the development of a cultured or educated man (jun zi).[73] Also emphasized are ideas that education should eschew rote learning and that the virtue of education lies in self-actualization that benefits the community and the country.[74] 3 Idiots, in its narrativization and critique of Indian education, introduces values and ideas about knowledge and learning that reflect similar beliefs, even though they come from a different national and cultural context. Moreover, the temporal parallels of India’s and China’s globalization in conjunction with the struggles of mammoth populations reveal similar issues created in the context of national growth and development. As the film grapples with the relationship between the collective and the individual, it mirrors Chinese anxieties in the face of a changing ethos in which China is also experimenting with its own capitalist model.

As opposed to a distinctive Western individualism that is congenial to modernity and accentuated by processes of modernity, Confucianism advocates a self in social harmony and expects communal participation as the individual’s “adjustment to the world.”[75] The initial ideological struggle of the Chinese Mainland, as Chinese American philosopher Tu Wei Ming explains, was a struggle between socialism and capitalism.[76] While an early film like Awaara encapsulated a socialist vision, 3 Idiots posits similar struggles wherein the main protagonist emphasizes values of humanity, rightness, and wisdom in his vision of true learning. At the same time, Rancho privileges self-fulfillment. The two films address the ethics of imposing societal will on the individual, a tenuous dynamic with which both countries must grapple. The deep friendship between the three idiots—Rancho, Farhan, and Raju—and their struggles thus resonate with normative pressures of filial piety, a core tenet of Confucian thought.

Another distinctive aspect of Bollywood that young Chinese audiences had difficulty contending with is Bollywood’s non-conformity to Western genres. The Bollywood masala film is a culmination of rasas that bring together the essence of a range of human emotions.[77] The genre seeks to encapsulate every core human emotion from happiness to rage and presents itself as an amalgamation of comedy, romance, action, song, dance, and melodrama. Audiences remarked on the genre’s novelty and difference. Many termed it exotic, revealing a lateral exoticization that throws the orient/occident dichotomy into disarray. A blogger on Mtime notes that “in this movie, we can still see the national characteristics of many Indian movies, such as singing and dancing” as distinctive “Indian humor.”[78] Another commenter added, “Indian movies always do some inexplicable singing and dancing.”[79] This lateral exoticization of another Asian culture points to a dynamic wherein the Chinese perception of the national self is filtered through the lens of Western acceptance. Yet another commenter remarked that Bollywood singing and dancing were featured on The Big Bang Theory (CBS, 2007–2019), inflecting the commenter’s perception of it and underscoring that exoticization and orientalism do not exist as an East/West binary.[80] This deliberate othering functions as a geopolitical construct propounded by state narratives of rivalry. The othering of India in a convoluted way reveals how Chinese audiences understand themselves. But before we examine this further, let us first return to the value proximities that enabled the initial audience affinity for the film.

The online momentum triggered by 3 Idiots created a perception of Aamir Khan as the embodiment of the film’s values. His next film, PK, which he promoted in China, received its Chinese theatrical release on May 22, 2015. While 3 Idiots represented a serendipitous circumstance for cultural flows and soft power, PK was closely orchestrated by the industry. Khan was presented to the Chinese audience again, and this time Bollywood eagerly anticipated the star’s reception. During this phase, the Indian government led by Prime Minister Modi—the harbinger of celebritized politics in the country—became aware of Aamir Khan’s popularity in China and met with him.[81] India’s industrial and state-led efforts hoped to marshal Khan’s newfound popularity in China. Huaxia Film Distribution, China’s second-largest distributor, distributed PK in partnership with UTV, one of India’s established and globally ambitious media organizations.[82] The careful industry attention toward this film and its performance in the Chinese market was visible in their attempt to create a good dubbed version for China. Khan’s voice in the film was dubbed by Chinese superstar Baoqiang Wang in Putonghua—the standard spoken form of modern Chinese based on the Beijing dialect—in an attempt to strike a chord with a young Chinese audience. In addition, Jackie Chan was hired for the promotion tour.[83] Modi leveraged the industry’s attention, symbolically gestured to soft power through Ayurveda, Yoga, and Bollywood during his visits to Buddhist sites in China that pointed to cultural connections.[84] PK emerged at the top of the Chinese box office, second only to Avengers: Age of Ultron (Joss Whedon, 2015), earning 100 million yuan, a first for any Bollywood film.[85]

PK was critical to cementing Bollywood’s and Khan’s popularity in China and establishing the tenor of Khan’s star persona as socially conscious. PK follows an alien who comes to Earth on a research mission and questions religious dogmas and superstitions. The industry and Indian state positioned and mobilized PK to encourage collaboration. Following PK’s success, India and China decided to address their growing trade deficit through films. Collaborative ventures such as Kung Fu Yoga (Stanley Tong, 2017) appeared in the wake of the newfound cinematic bonhomie of the 2010s, and a few social issue-oriented Bollywood films received Chinese releases.[86] State-driven efforts, however, were not consistently coordinated in the wake of PK because Bollywood’s relationship with the Indian state was disjunctive at best. Soft power efforts, therefore, have mirrored the waxing and waning rhythms of Indo-Chinese geopolitical ties. Nevertheless, Khan and his fandom remained constant. The Chinese connection to Bollywood and India remained centered on Khan, with his fans seeking more content. Many of his older films circulated through piracy networks, leading to convergent affects that brought together fan spaces on social media, technology networks, and film and television. They discursively allowed the Chinese audience to engage with and construct Khan’s star persona. His TV talk show, Satyamev Jayate, gave the audience direct engagement with the star.[87] Additionally, the show directly addressed the audience and constructed him as a socially conscious star.

Deconstructing audience affinities toward Khan unpacks how soft power and influence can operate through individual social actors. Khan’s affective power and fandom developed through his early films 3 Idiots and PK, and Khan’s TV show Satyamev Jayate mediated the transferal of values reflected in his early films onto the star himself. This convergent affect, refracted through television, shaped representations and valuations of Khan’s celebrity. He became a star too big to be contained by one screen.[88] Misha Kavka argues that convergent affects are augmented through the multiplication of screens on which a star appears and the socio-technological interconnection of those spaces. Khan’s direct address in the talk show was amplified by his self-personification on Chinese social media platforms, on which he embodied India’s conscience.[89]

Satyamev Jayate first aired in India in 2012 in eight languages, receiving excellent ratings.[90] Produced by Khan’s production company and broadcast on STAR India, the show focused on social issues ranging from honor killings, abuse, and rape to female feticide and the criminalization of politics. Executives remarked, “after the first season of Satyamev Jayate, we got inquiries [to acquire rights for the show] from all over Asia, but the highest number of inquiries came from China.”[91]

The show was broadcast in China starting in 2014. The overwhelming response to Khan cemented his socially conscious persona. Over a thousand Douban user comments hailed him as a “deserving modern hero of India.”[92] One commenter noted, “[Khan] often wipes away his tears and uses hugs to comfort the injured, but he is not angry, does not complain, and does not incite emotions.”[93] Other fans proudly identify him as “a great God” and the “conscience of India.”[94]

Douban comments reflected how the affective associations evoked by Khan’s socially conscious star persona exceeded the national and industrial dichotomies between India and China: “Aamir Khan is more than an actor. What makes me admire him the most is not only his movies but also his television talk show, Satyamev Jayate. Every episode insightfully points to a social issue that plagues modern India, and each episode has also achieved wide social attention.” Another user added, “It is as if you can see genuine enthusiasm for movies and compassion for his fellow Indians just from his eyes. It is hard to find people with a big heart like his in China’s film industry. They are rather a bunch of business people in China’s film industry; while our Indian neighbors are already conversing with God, we are still rolling around in the mud.”[95] Satyamev Jayate solidified Khan’s appeal and commitment to telling stories that evoked value proximities with the Chinese.

Two types of audience engagement emerged in comments addressing Satyamev Jayate. The first focused on comparative constructions of India and China. These commenters assessed India’s and China’s relative industrial and national progress and societal values. The second category often projected those values onto Khan. One user stated, “Aamir Khan has changed my views of Indians and Indian stars, who face up to all kinds of bad habits and diseases in India, and he works hard to change them with his own strength. Among Chinese politicians, businessmen and celebrities, I have not seen a person like this.”[96] Another user pointed to India’s and China’s similar problems but lamented that the Chinese problems were ignored due to censorship.[97] In analyzing Khan’s television stardom, Akshaya Kumar underscores its focus on performative justice and a sacrificial trope imbued within Khan’s on-screen persona that lent the actor political agency.[98]

Khan’s Dangal represented a culminating point in demonstrating the agentic power of his socially conscious and culturally resonant star persona that was progressively built through his films, and now both the Chinese and Indian states were cognizant of its potential. While making the film, Nitesh Tiwari, the director of Dangal, twice revealed that his approach centered on making a good film. He remarked on the uncertainty of any film doing well in the country’s diverse regional territories, let alone the international market.[99] Unlike Hollywood’s overt attempts to woo the Chinese market through strategic co-productions, plot changes, and themes boosting Chinese nationalism, the Indian industry lacked a top-down strategy.[100]

Dangal, criticized for its muscular nationalism, was an improbable candidate for a positive reception in China.[101] In contrast to Hollywood films that have been trying to temper their national impact by adding market-specific dialogue—such as “thanks to my Uncle Tommy in China, we get another chance at this”—to tentpoles like The Martian (Ridley Scott, 2015), Dangal’s appeal mainly came at the marketing stage. Its marketing focused on Khan and the spectacle of song and dance quintessential to the masala genre. Khan performed to Dangal’s music with his Chinese fans and trained Chinese dancers at various venues.[102] As a result, Dangal exceeded industry expectations, joining the ranks of the top twenty films in the history of Chinese cinema, collecting over $300 million and becoming China’s fifth highest-grossing non-English movie.[103] The summit and the Xi-Modi bonhomie over Dangal soon followed. Its enormous success entered state discourse and diplomacy to de-escalate a possible military conflict. Here, the idea of affective soft power generated by individual social actors came into play, instantiated through audience engagement with an individual star and the texts and contexts about the star. Khan’s centrality as a stand-alone social actor in Indo-Chinese diplomacy results from Bollywood’s relationship with the Indian state. Unaware of the industry’s potential, early leaders of independent India ignored popular Hindi cinema that existed tenuously and illegitimately on the margins, with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (1947–1964) claiming the film industry promoted “a type of vulgarity” that lowered society’s cultural and moral standards.[104] Post-independence, Indian leadership hesitated in sending their supposedly vulgar popular cinema abroad. Unlike China or Russia, which deliberately employed media for propaganda, or even the United States, whose industry was strategically aligned with the state’s soft power goals, Bollywood was different. As Straubhaar contends, “depending on the nature of the state and economy of a country, much of its soft power is likely to be generated by private, commercial national cultural industries” that produce most exports and reflect the “the broader nation as opposed to directly expressing the will of the state.”[105] Indian films such as Dangal and Khan’s popularity in China are not propaganda laboriously geared toward generating soft power and overtly orchestrated by the state.[106] Khan’s popularity reveals a dimension of attraction that was mediated through fandoms created and sustained at the level of the people and their interactions and understanding of Khan as an individual social actor.

Dangal’s two women wrestlers defy the sport’s patriarchal expectations when they wrestle professionally and win a gold medal despite a lack of resources and proper sports infrastructure in rural Haryana. The dichotomy in the story is that although they take up a masculine sport and excel at it, their willingness stems not from an innate desire but filial piety and obligation toward their father. The glory they earn is framed collectively—glory for the nation—and their victory is a step forward for womanhood. The film shows the young girls’ rebellion against the father’s authority, but, in the end, the benevolent patriarchal order is restored. The story leads to triumph for the individual and the nation-state. The liberal urban Chinese audience’s response to Dangal focuses on this push and pull, the conflict with Confucian values, and the social conflict generated by China’s selective adoption of a capitalist market economy and its inherent value systems.

The film generated much discussion about women’s freedom with comments assessing ideas of filial piety. One commenter noted, “I don’t think this movie falls into the trope of patriarchy. Although the father hopes his daughters will achieve his dream, it is based on the daughters’ demonstrated talent in wrestling. Wrestling helped the two girls escape the fate of prejudice [and] endless domestic chores.”[107] Another opined, “It is absolute nonsense to judge the values of this film without looking at the larger social context.” The commenter added a reading of the father’s admonition: “you are not only fighting for yourself, but you are also helping hundreds of thousands of women to see that being a woman not only entails getting married and taking care of the household. Ultimately, the significance of this struggle is far beyond realizing the father’s dream.”[108] Another noted the context and the comparative socio-cultural construct: “if you put this movie into perspective to interpret it from the viewpoint of India’s social reality, [you will find] the movie is neither paternalistic nor patriarchal.”[109] The user felt that familial love was the connector. Others pointed to the Western gaze that Chinese users imparted to the film by viewing it through a strictly feminist lens and commenting on the position of women in Indian society: “First of all, [the film] by no means represents the whole of India. The way we look at India is like how the Western world has looked at China for many years.”[110] Commentators also noted Khan’s dedication to a collective social consciousness, to raising social awareness, and ultimately to his acting profession: “Aamir Khan’s works are never superficial or stop at the surface. Behind each of his works is his exposure and critique of a particular aspect of injustice in Indian society.”[111] Many talked about Khan’s losing and gaining weight to portray the father at different life stages.[112] Others were enamored by Khan’s desire, which reflected the Indian people’s desire to re-establish themselves in the realm of sports.[113] Furthermore, unlike Khan’s earlier films, which mainly found a middle-class urban audience, Dangal became popular in rural China.[114]

Through his socially conscious branding and dedication to moral values, Khan has built his star persona and become an important Bollywood node. Following the success of Satyamev Jayate, Khan was re-branded as an incarnation of universal morals, as he sought to create televisual moments of social epiphany that would instill collective transformation led by India’s burgeoning middle class. Journalistic coverage in India and beyond, most prominently the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, hailed him as the conscience of Indian television.[115] The show presented social possibility through the audiences’ affective lives, where they imagined and enacted possibilities of despair and hope. Akshaya Kumar relates this persona to a metamorphosis highlighting a sacrificial trope that directly attached Khan to political agency.[116] Anticipating this, Khan rejected advertising revenue from Satyamev Jayate: “I just felt that while I am doing this show, I didn’t want to be selling something. . . . It didn’t feel right.”[117] Of course, the star was paid thirty-five million rupees ($630,000) for each episode.[118] Roopali Mukherjee and Sarah Banet-Weiser have articulated this neo-liberal commodity mediascape wherein celebrities use their star capital to encourage consumers to co-produce their commodity-derived activism.[119] In this instance, Khan’s star capital exceeded other corporate nodes and established political exceptionality. This performative excess through Satyamev Jayate that re-casted Khan into a selfless savior and champion of all social causes ranging from feticide to telecom policy played a crucial role in defining his superlative star identity and in situating him as a stand-alone political actor in the context of the Indo-Chinese state interactions and diplomacy.

It is thus hardly surprising that his Chinese fans know and address him as “India’s conscience.” So, what factors engender this affective pull built around an individual social actor’s consciousness, moral fiber, and dedication? If it is, as Dorothy Wai Sim Lau argues, “a cosmopolitical” phenomenon premised on generalizing Khan’s specific strategy for global stardom by recognizing humanity, why is Khan’s global popularity limited to China?[120]

Khan’s popularity is not about generalizations but deeply felt specifics. As a Chinese viewer observed, “There is a scene in the film [Dangal] when Aamir Khan tells his daughter, ‘As your father, I can only teach you, but I cannot save you every time.’ The Buddha is also our father and teacher. He teaches us to live the right way but cannot save us. Not only the Buddha but also Confucius, Lao Tzu, and all the wise men all over the world who try to awaken sleeping people to realize the truth.”[121] Proclaiming Khan to be the conscience of India, the commenter further asserted that “conscience is our true nature, and [Dangal] has touched our true nature.”[122] The evocation of “true nature” is particularly noteworthy in this context because Confucianism explicates the parent-child relationship as a role that correlates to the natural way—a reference to the idea of Tao (truth or way) that forms the basis for spiritual and natural force and understanding. In other words, Tao, or the natural way, is the highest goal a person can reach.[123]

Several value proximities tied to gender mirrored across Indian and Chinese societies were also reflected in Dangal. It enunciated the cracks in the Indian social and familial structure that prefers boys to girls, a parallel reality that both societies struggle with. Frederick Leung underscores this idea by identifying the Confucian patriarchal hegemony remanent in Chinese society: “the birth of a daughter in traditional China was a disappointment; the birth of a second daughter brought grief and perhaps death to the infant; the birth of a third daughter was a tragedy for which the mother was most assuredly blamed.”[124] Raising a daughter was akin to “watering another man’s garden.”[125] In Dangal, Khan’s character has similarly lost hope after the birth of his third daughter and later reclaims the hope for patrilineal glory upon realizing that a daughter, too, can bring laurels to his family, village, and motherland. The cultural parallels are indeed close as the film touches upon how patriarchy works in Eastern societies. Khan is the benevolent patriarch who hones his daughters’ potential and trains them with rigor and discipline until they win accolades for the country. Filial piety is the highest duty in the parent-child role within Confucianism. The daughters in Dangal, despite their initial resistance and rebellion, learn their indebtedness to the patriarchal family and nation. In one scene, another teenage girl on the verge of getting married confesses to Phogat’s daughters, “at least your father cares about you.”

Dangal, however, provided multiple reverberant values and morals as well as similar material developmental conditions such as the rural-urban divide, migrant workers having to leave home because of the rise of capitalism, and gaps in infrastructural development in rural versus urban areas. Multiple value proximities in conjunction with parallel modernities tied to development thus form the crux of Dangal’s appeal. According to Beijing Film Academy scholar Ten Zhen, “[Dangal’s] story is very Chinese,” paralleling the experience of many Chinese female athletes who move from the countryside in hopes of becoming world champions.[126] Zhong Bingshu, the dean of Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, notes, “there are so many Chinese Olympic champions such as Wang Junxia [Chinese long-distance runner] who, like Geeta, came from the lower classes. The film shows how a common person becomes a champion and how that feels. Audiences want to know how these people achieved their dreams, but our Chinese sports films rarely ever do that.”[127] Shanghai white-collar worker Sandy Liu emphasizes how Indian films can mock bureaucracy and show the emergence of feminism using humor in a way that Chinese films cannot.[128] Film critic Feng Jun reasserts this claim, stating that Indian movies “touch on various social issues, which in China, because of policy factors, can’t be done.”[129]

The value of affect, Janet Staiger notes, lies in the strength of the emotion it evokes and how affective cinematic experiences constitute cultural and ideological value.[130] This affective politics, however, takes on significant meanings as it intersects with real geopolitical interests. The enormous success of Dangal, the third consecutive Aamir Khan film to delight Chinese audiences, was leveraged by the national diplomatic apparatus on both sides to de-escalate tensions, but Dangal and Khan do not represent typical state-centric soft power instruments. For one, Bollywood’s presence in China was driven by industry efforts, not the state, which came on board to leverage what already existed. Second, the Chinese state has deliberately constructed Khan as an individual, distinctive, and separate from the Indian nation-state. It intended to establish that devotion to Khan and his films did not mean an attraction to India, thus hoping to diminish soft power gains for their neighbor. Sohu, China’s top search engine and community web (articles on the site are censored by the state), explains Khan’s popularity in China:

India is a country deeply influenced by the caste system and . . . various social problems but it is difficult for Indians to find out. They see it and pretend them to be invisible. Amir [sic] Khan’s vision allows him to look beyond his environment to look at the entire environment, so he can know the real problems in this country. Aamir Khan is very popular in China because of his movies and much criticized by Indians also because of his movies. As a perfectionist, he always listens to his inner voice to make choices. Because of this show, Amir [sic] was respected by many people and, at the same time, hated by many more. In a country where most people are sleeping, some of the people who are awake will pretend to be asleep, and the rest will wake the whole country up, even if they know they will be pummeled afterward. Amir [sic] Khan is an actor who is India’s national treasure. In fact, no matter which country you put him into, he is a national treasure.[131]

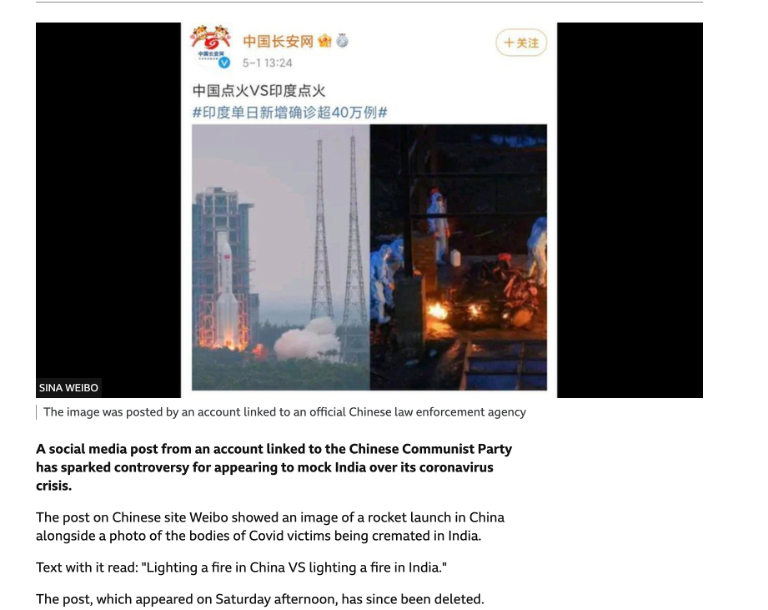

Sohu constructs Aamir Khan as an individual who exceeds the typical Indian ethos, which is generally construed as corrupt. Accordingly, Indians do not value and respect him as the Chinese do. This deliberate positioning of Aamir Khan in an article likely evaluated by Chinese censors points to the possibility that Khan as an individual actor is beneficial, but his association with India or the resultant attraction to India that his popularity might generate is not. So why and how does Khan become an intermediary soft power node between two powerful geopolitical actors? India-based Chinese entrepreneur and Fulbright scholar Hu Jianlong has written about China’s “inability to export its ideals and values due to its government’s self-sabotaging campaigns against freedom of expression.”[132] Dangal accomplished what the “Chinese Communist Party has been trying to do in vain [for China’s soft power through their own media] since at least 2009.” Hu further notes, “China’s state media has a long tradition of playing down and disparaging India. Beijing’s propaganda machine often portrays India as a nation of failure.” Linking India’s “backwardness to its democracy” helps Beijing establish its “totalitarianism” and “successful . . . socialism with Chinese characteristics.”[133] But Dangal persuaded millions of Chinese to reconsider their views about India. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic—when India seemed to suffer the highest number of daily deaths and ties between India and China frayed again due to continuing border disputes—the CCP posted a picture on its Weibo account mocking the burning funeral pyres in India, likening them to the image of a rocket launch. Its caption read, “Lighting a fire in China vs. lighting a fire in India” (see Figure 2).[134]

The post led to a backlash on Weibo from Chinese users who were appalled at the state’s insensitivity, and the post was promptly taken down and followed by announcements of Chinese support for India. When Khan came down with COVID-19, the news from India was reported widely in China. A post on Weibo generated multiple responses that have been inaccessible and blocked from view. However, an exploration of other platforms such as Zhihu, a Chinese Reddit, spoke to the audience’s deep empathy for Indians and for Khan. While users were critical of government inefficacy and unhygienic practices in India, Khan and India, as channeled through his condition, were construed with affinity and commiseration. One user noted, “last year, Aamir Khan was one of the rare international movie stars who spoke out for China, sent encouragement and blessings.”[135] Another expressed fear for Indians and hoped India would get a vaccine.[136] People extended their empathy with India: “Uncle Mi [Khan’s nickname] is a high caste and upper class in India. . . . It can only be said that the epidemic situation in India is very, very serious now!”[137] Many others reflected on the Indian federal democratic state and how strict, large-scale preventive policies could be implemented.[138] A user comment summed up the affective engagement around lateral proximities and affinities that this article has been foregrounding as the key aspect of affective soft power through non-state actors like Khan: “I hope that Aamir Khan will recover soon, that 1.3 billion Indians will achieve collective immunity after vaccination as soon as possible, and that China and India will maintain direct, candid, and sincere trust instead of being influenced by ‘stuck’ Britain and ‘Voldemort’ America. India is bewitched by them.”[139]

This favorable response from Chinese netizens was an instantiation of how attraction worked beyond state-centric discourses and how affective investment in individual social actors such as Khan helped define those attractions creating a contiguous resonance rooted in the shared experiences and developmental realities. This article thus articulates the deep-seated and often neglected affective underpinnings of soft power attached to individual social actors and reframes it within the context of the new cinephilia that accords value to subjective experiences beyond established West-centric hierarchies. More emphatically, it recognizes audience agency within the discourse of soft power, traditionally seen as state orchestrated. This audience-focused discourse amorphously exceeds the strict limits of the nation-state and simultaneously compels the nation-state to accommodate individual actors such as Khan. Thus, the Indian embassy in Beijing, in the wake of escalating tensions due to COVID-19, hosted Aamir Khan’s birthday for his Chinese fans, who understood shared goodwill beyond the Chinese state propaganda and hoped that “Khan hasn’t fallen into narrow [Indian] nationalism.”[140]

This article was almost a decade in making. It started as an independent study with Janet Staiger when my curiosity was piqued by the popularity of 3 Idiots in China and East Asia. So many people have helped me along the way in bringing this article to fruition: Sara Liao, Shanti Kumar, Joe Straubhaar, Wenhong Chen, Giulia Ricco, Al Martin, Pete Kunze, Caetlin Benson-Allott, Samantha Sheppard, Anupama Kapse, and my amazing undergrad research assistants at the University of Michigan and Wesleyan University.

Press Trust of India, “Chinese President Xi Jinping Watched Aamir Khan-Starrer ‘Dangal’ on Multiple Occasions, Says China Envoy to India,” Financial Express, updated June 18, 2018, accessed July 1, 2019, https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/chinese-president-xi-jinping-watched-aamir-khan-starrer-dangal-on-multiple-occasions-says-china-envoy-to-india/1211038/. ↑

“I Watched Dangal and Liked It: Chinese President Xi Jinping Tells Prime Minister Modi,” V6 News Telugu (Hyderabad), June 10, 2017; and “President Xi Told Me He Has Watched Dangal, Says Prime Minister In Haryana Rally,” NDTV (New Delhi), October 15, 2019. ↑

Overt examples of state-cultivated attractions would be China’s CCTV, Russia’s RT news channel, or US media channel Alhurra in the Middle East. ↑

Joseph S. Nye Jr., Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 1991). ↑

Michael Curtin, “Newton Minow’s Global View: Television and the National Interest” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Portland, OR, July 2–5, 1988). ↑

Ty Solomon, “The Affective Underpinnings of Soft Power,” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 3 (2014): 720–741. ↑

Kristin Shi Kupfer et al., “Ideas and Ideologies Competing for China’s Political Future,” MERICS Papers on China (Mecator Institute for China Studies) 5 (2017): 9–91. ↑

Solomon, “Affective Underpinnings.” ↑

See Solomon, and Ulrich Beck, Power in the Global Age: A New Global Political Economy (New York: Wiley, 2014). ↑

Peter M. Hall, “Meta-power, Social Organization, and the Shaping of Social Action,” Symbolic Interaction 20, no. 4 (1997): 397–418. ↑

For more on Western cultural hegemonic influence, see John Tomlinson, “Internationalism, Globalization and Cultural Imperialism,” in Media and Cultural Regulation, ed. Kenneth Thompson (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997). ↑

For more, see Girish Shambu, “For a New Cinephilia,” Film Quarterly 72, no. 3 (2019): 32–34. ↑

Melis Behlil, “Ravenous Cinephiles: Cinephilia, Internet, and Online Film Communities,” in Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, ed. Marijke de Valck and Malte Hagener (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005), 111–124. ↑

Behlil. ↑

Shambu, “For a New Cinephilia,” 32–34. ↑

Behlil, “Ravenous Cinephiles.” ↑

For parallel modernities, see Brian Larkin, “Indian Films and Nigerian Lovers: Media and the Creation of Parallel Modernities,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 67, no. 3 (1997): 406–440; for cultural proximities, see Joseph D. Straubhaar, “Beyond Media Imperialism: Asymmetrical Interdependence and Cultural Proximity,” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8, no. 1 (1991): 39–59. ↑

I used Google Translate for all initial translations from Chinese to English. Those translations were reviewed by my two research assistants, Yuyao Sun and Xinyue Zhang, who have native fluency in Mandarin and Cantonese. ↑

Shambu, “For a New Cinephilia”; and Guobin Yang and Shiwen Wu, “Remembering Disappeared Websites in China: Passion, Community, and Youth,” New Media and Society 20, no. 6 (2018): 2107–2124. ↑

Rui Yang, “Interview with Aamir Khan, the Biggest Bollywood Star in China,” Ideas Matter: Dialogue with Yang Rui, aired December 28, 2018, on China Global Television Network. ↑

Liu Zhongyin, “China Celebrates 10th Anniversary of Indian Movie ‘Three Idiots,’” Global Times, December 26, 2019, accessed February 15, 2020, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174909.shtml. The film was hailed as the film of the century by Chinese netizens. ↑

阿米尔汗资讯台 [Aamir Khan Information Channel], Weibo, n.d., accessed July 30, 2021, https://weibo.com/filan?is_all=1. ↑

Coco Liu, “Meet the Secret Superstar of China, from India: Aamir Khan,” South China Morning Post, January 28, 2021, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/society/article/2130746/meet-secret-superstar-china-india-aamir-khan. ↑

Arunabh Ghosh, “Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History,” Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3 (2017): 697–727. ↑

Press Trust of India, “China Hails Move to Appoint Aamir Khan as Brand Ambassador to Promote Trade Read,” Economic Times, April 27, 2018, accessed January 29, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/china-hails-move-to-appoint-aamir-khan-as-brand-ambassador-to-promote-trade/articleshow/63929927.cms. ↑

Abhishek G. Bhaya, “China Lauds India’s Move to Make Aamir Khan a Brand Ambassador,” China Global Television Network, April 27, 2018, accessed January 15, 2019, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d414d3149544d77457a6333566d54/share_p.html. ↑

Khan’s brand ambassador appointment never materialized because of another border conflict, revealing the haziness of soft power and its unquantifiable nature. ↑

搜狐 [Sohu], 为什么阿米尔汗在中国非常火,却遭印度人一片骂声? [Why is Aamir Khan very popular in China, but was criticized by Indians?], Sohu, July 24, 2018, accessed January 8, 2019, https://www.sohu.com/a/243077075_475369. ↑

The legitimation entailed formal bank financing and was intended to pull Bollywood out of the criminal economy financing networks. Laya Maheshwari, “Why Is Bollywood Such a Powerful Industry? Mumbai Provides an Answer,” IndieWire, October 29, 2013, accessed January 10, 2019, https://www.indiewire.com/2013/10/why-is-bollywood-such-a-powerful-industry-mumbai-provides-an-answer-33491/. ↑

“Guess Who Is Promoting His Film while Modi Is in China,” India Today, May 14, 2015, accessed February 5, 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/asia/story/aamir-khan-china-beijing-pk-narendra-modi-252944-2015-05-14. ↑

“Promoting His Film.” ↑

Yang and Wu, “Remembering Disappeared Websites.” ↑

Josh Rudolph, “After Shuttering of Feminist Douban Groups, Women Call for Unity Online,” China Digital Times, April 16, 2021, 1. ↑

“Mtime.com Inc,” Bloomberg, accessed April 23, 2012, https://www.bloomberg.com/profile/company/0573255D:CH; and Jonathan Landreth, “Making (M)Time in China,” Hollywood Reporter, November 1, 2007, 6. ↑

See Yang and Wu, “Remembering Disappeared Websites.” ↑

Junzhou Zhao et al., “Empirical Analysis of the Evolution of Follower Network: A Case Study on Douban,” IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (2011): 924–929. ↑

Terry Flew, “Entertainment Media, Cultural Power, and Post-Globalization: The Case of China’s International Media Expansion and the Discourse of Soft Power,” Global Media and China 1, no. 4 (2016): 278–294. ↑

Anil K. Gupta, Girija Pande, and Haiyan Wang, The Silk Road Rediscovered: How Indian and Chinese Companies Are Becoming Globally Stronger by Winning in Each Other’s Markets (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014). ↑

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “India–China Relations,” Ministry of External Affairs (New Delhi), January 2014, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/China_January_2014.pdf. ↑

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Cultural and Goodwill Mission to China under the Leadership of Mrs. Pandit, public record (New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1952). ↑

Aruna Vasudev, The New Indian Cinema (New Delhi: Macmillan India, 1986). ↑

James D. Decker and Patrick S. Brennan, “Political Propaganda in the Feature Film Industries of Nazi Germany and Maoist China,” Rupkatha Journal: On Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 6, no. 3 (2014): 51–61. ↑

On the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, see Tom Philips, “The Cultural Revolution: All You Need to Know about China’s Political Convulsion,” The Guardian, May 10, 2016, accessed June 10, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/11/the-cultural-revolution-50-years-on-all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-political-convulsion. ↑

Gupta, Pandey, and Wang, Silk Road. ↑

Alison W. Conner, “Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens?,” Law Text Culture 18, no. 4 (2014): 33–55. ↑

Nitin Govil, “China, between Bombay Cinema and the World,” Screen 60, no. 2 (2019): 342–350. ↑

Gupta, Pandey, and Wang, Silk Road, 2. ↑

Krista Van Fleit Hang, “‘The Law Has No Conscience’: The Cultural Construction of Justice and the Reception of Awara in China,” Asian Cinema 24, no. 2 (2013): 141–159. ↑

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Indian Policy towards South-East Asia, Research and Analysis Wing (New Delhi: Government of India, 1976). ↑

Elaine Yau, “How Bollywood Hit the Mark in China; Indian Films Have Started to Make a Splash on the Mainland, Due in Part to the Struggles Both Countries Face in Addressing Poverty and Modernisation,” South China Morning Post, December 12, 2018, 9. ↑

“Lagaan to Be Released in China,” Times of India, October 13, 2003, 1. ↑

Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India, Douban, June 15, 2001, accessed June 15, 2019, https://movie.douban.com/subject/2254631/comments?percent_type=h&limit=20&status=P&sort=new_score. ↑

“Movie,” Douban, December 8, 2011, accessed March 8, 2012, https://movie.douban.com/subject/3793023/. ↑

Landreth, “Making (M)Time in China.” ↑

Rob Cain, “How a 52-Year-Old Indian Actor Became China’s Favorite Movie Star,” Forbes, June 8, 2017, accessed July 1, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/robcain/2017/06/08/how-a-52-year-old-indian-actor-became-chinas-favorite-movie-star/. ↑

Patrick Brzeski, “How Bollywood Became a Force in China,” Hollywood Reporter, May 12, 2018, accessed December 1, 2019, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/how-bollywood-became-a-force-china-1111394/. ↑

Alex Dobuzinskis, “DreamWorks Completes Deal with Reliance ADA,” Reuters, September 23, 2008, accessed November 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/industry-us-dreamworks/dreamworks-completes-deal-with-reliance-ada-idUSTRE48M2T720080923. ↑

“3 Idiots on a Record-Breaking Spree across the World,” Times of India, January 10, 2017, accessed February 10, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/box-office/3-idiots-on-a-record-breaking-spree-across-the-world/articleshow/5391904.cms. ↑

Brian Larkin, “Degraded Images, Distorted Sounds: Nigerian Video and the Infrastructure of Piracy,” Public Culture 16, no. 2 (2004): 289–314. ↑

“The IIT Entrance Exam,” Priceonomics, June 27, 2013, accessed April 5, 2020, https://priceonomics.com/the-iit-entrance-exam/. ↑

Rebecca Leung, “Imported from India,” CBS News, June 19, 2003, accessed January 12, 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/imported-from-india/. ↑

The film depicts several suicide attempts by students that mirror reality at the IITs. Pritika Ghura, “IITs Rocked by 7th Suicide This Year: Is the Academic Pressure Killing Students?,” JEE Learn Hub, September 2011. ↑

达达先生 [Dá Dá Xiānshēng], 《三个白痴》——像风般自由) [3 Idiots—free like the wind], Mtime, September 16, 2010, accessed October 15, 2014, http://content.mtime.com/review/4963035. ↑

昨夜西风凋碧树 [Zuóyè xīfēng diāo bì shù; Last night the west wind withered the green trees], 《三个白痴》:人生三叹皆是憾 [3 Idiots: Three sighs in life are all regrets], Mtime, November 19, 2010, accessed May 10, 2014, http://content.mtime.com/review/5192233. ↑

Luc_Fr., Mtime, December 23, 2011, accessed May 10, 2014, http://movie.mtime.com/93049/reviews/7186492.html. ↑

鱼鱼菲菲 [Yúyúfēifēi], 三傻大闹宝莱坞的影评 [3 Idiots making a scene in Bollywood], Douban, May 9, 2017, accessed May 15, 2017, https://movie.douban.com/subject/3793023/reviews. ↑

简芳 [Jian Feng], 转南方都市报:印度励志片《三个白痴》引国内网友强烈共鸣 [Southern Metropolis Daily: Indian inspirational film 3 Idiots draws strong resonance from domestic netizens], Internet Archive: Wayback Machine, August 8, 2010, accessed May 15, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170515165636/http://movie.mtime.com/93049/reviews/4794323.html. ↑

Janet Staiger, “The Centrality of Affect in Reception Studies,” in Film – Cinema – Spectator: Film Reception, ed. Irmbert Schenk, Margrit Tröhler, and Yvonne Zimmermann (Marberg: Schuren Verlag GmBH, 2010), 85–98. ↑

Janet Staiger, Ann Cvetkovich, and Ann Reynolds, Political Emotions: New Agendas in Communication (London: Routledge, 2010), 1–17, 4. ↑

In this framework, alongside Staiger, I utilize Larkin’s ideas of parallel modernities and Straubhaar’s notion of cultural proximities and reframe them in this context as Confucian value proximities. Staiger, “Centrality of Affect,” 86; and Brian Larkin, “Bollywood Comes to Nigeria,” Samar 8 (Winter/Spring 1997), http://www.samarmagazine.org/archive/article.php?id=21. ↑

Xiao-Ping Chen et al., “Affective Trust in Chinese Leaders: Linking Paternalistic Leadership to Employee Performance,” Journal of Management 40, no. 3 (2014): 796–819. ↑

Ithamar Theodor and Zhihua Yao, Brahman and Dao: Comparative Studies of Indian and Chinese Philosophy and Religion (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014). ↑

Shane N. Phillipson, “Confucianism, Learning Self-Concept and the Development of Exceptionality,” in Exceptionality in East Asia: Explorations in the Actiotope Model of Giftedness, ed. Shane N. Phillipson, Heidrun Stoeger, and Albert Ziegler (London: Routledge, 2013), 40–64. ↑

Frederick K. S. Leung, “The Implications of Confucianism for Education Today,” Journal of Thought 33, no. 2 (1998): 25–36. ↑

Peter L. Berger, “An East Asian Development Model?,” in In Search of an East Asian Development Model, ed. Peter L. Berger and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao (New York: Routledge, 1988). ↑

Tu Wei-Ming, “The Rise of Industrial East Asia: The Role of Confucian Values,” Copenhagen Papers in East and Southeast Asian Studies 4 (1989): 81–97. ↑

Haptic visuality and rasa aesthetics, Rajinder Dudrah and Amit Rai argue, are “the embodied life of the sensations of Bollywood.” Rajinder Dudrah and Amit Rai, “The Haptic Codes of Bollywood Cinema in New York City,” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 3 (2005): 143–158. ↑

伯爵 [Bójué], 《三个白痴》:嬉笑怒骂中小窥印度电影工业 [3 Idiots: A glimpse of the Indian film industry], Mtime, August 13, 2010, accessed February 26, 2012, http://content.mtime.com/review/4785807. ↑

Bójué. ↑

Bójué. ↑

Swapnil Rai, “‘May the Force Be with You’: Narendra Modi and the Celebritization of Indian Politics,” Communication, Culture and Critique 12, no. 3 (2019): 323–339. ↑

Urvi Malvania, “PK Creates History in China; Crosses Rs 100 CR at Chinese Box Office,” Business Standard, June 15, 2015, accessed January 19, 2018, https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/pk-creates-history-in-china-cross-rs-100-cr-at-chinese-box-office-115060900536_1.html. ↑

Malvania. ↑

Lawrence Chung, “Yoga and Modi’s Soft-Power Twist; The Indian Prime Minister’s Trip to China Is Designed to Highlight the Strong Cultural and Religious Ties between the Two Asian Giants,” South China Morning Post, May 15, 2015, 1–3. ↑

“‘PK’ Box Office Collections Ink Record with 100 Million Yuan Take in China, Aamir Khan, Anushka Sharma Celebrate Success,” Financial Express, June 7, 2015, accessed January 9, 2018, https://www.financialexpress.com/photos/business-gallery/81444/aamir-khans-pk-box-office-collections-ink-record-with-100-million-yuan-take-in-china/. ↑

An India-China MoU on audio-visual co-production was signed during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to India in September 2014, and two Indian movies, PK and Dhoom 3 (Blast 3, Vijay Krishna Acharya, 2013), were released in 2015. Xuan Zang (Huo Jianqi, 2016) was the first co-production film between India and China. It featured famous Chinese actor and model Huang Xiaoming and was submitted to represent mainland China for Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards in 2017. In 2017, Gong fu yu Jia (Kung Fu Yoga, Stanley Tong), featuring Jackie Chan, and 大闹天竺 (Dà nào tiānzhú; Buddies in India, Wang Baoqiang) were released. For more, see Embassy of India, Beijing, China, “India-China Trade and Economic Relations,” January 1, 2018, accessed January 15, 2019, https://www.eoibeijing.gov.in/economic-and-trade-relation.php. ↑

Vidhi Choudhary, “‘Satyamev Jayate’ Goes to China,” Mint, May 30, 2014, accessed April 14, 2018, https://www.livemint.com/Consumer/zOB5g2gKYCUSdJMO8ziNOP/Satyamev-Jayate-goes-to-China.html. ↑

Misha Kavka, “Celevision: Mobilizations of the Television Screen,” in A Companion to Celebrity, ed. P. David Marshall and Sean Redmond (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 295–314. ↑