Is Kingdom Hearts a JRPG? The Racialized Labor of a Japanese Anti-auteur’s Disney-Licensed Videogame

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

Abstract: The premise of Kingdom Hearts (2002), a Japanese role-playing game (JRPG) produced by Square that features Disney characters, led fans to question the game’s genre and reveals the tenuous connection between JRPG and the Japanese racial identity. The irony that Kingdom Hearts both inspires doubts about the Japanese-ness of JRPG and is widely associated with the Japanese auteur Tetsuya Nomura alludes to the industrial structure that deracinates JRPGs to render them exportable. This article elucidates the racialized labor behind Kingdom Hearts by reading Nomura as an anti-auteur who subverted Disney’s control to make a game that aligns with Square’s brand of JRPG.

When Square (currently Square Enix) and the Walt Disney Company first announced Kingdom Hearts (2002), which tells an epic space travel story about friendship and love featuring a huge cast of characters from Disney animations and Final Fantasy (1987–) games, online gaming communities expressed doubts about the game’s status as a Japanese role-playing game (JRPG). Because the game was produced by Square, one of the world’s leading JRPG developers, and was slated to include characters from Final Fantasy, arguably the most famous JRPG series in the world, Kingdom Hearts appeared on first glance to belong to the JRPG genre. But such assumptions were challenged when it became clear that American conglomerate Disney was involved in the project. How could Kingdom Hearts be a JRPG if iconic Disney characters were going to figure prominently in the game? Indeed, numerous online game forums posed the question directly: Is Kingdom Hearts a JRPG?[1] The unlikely collaboration between Disney and Square baffled longtime fans of JRPGs.

This issue was further exacerbated by the genre’s lack of definition. Whereas conventional JRPGs are story-driven games with a manga/anime aesthetic and turn-based combat, these characteristics no longer hold true for many contemporary JRPGs, which rely on an increasingly diverse set of attributes adopted from other genres, including Western RPGs. These include open world levels and action-based combat systems.

Despite the reservations of fans, Kingdom Hearts was a hit upon release and became one of the top ten best-selling PlayStation 2 titles of all time in North America, laying the foundation for a massive franchise.[2] The triumph of Kingdom Hearts turned its first-time director Tetsuya Nomura, who at the time was known more as a character designer, into a rising star within gaming communities, leading to his eventual recognition as a top Japanese game auteur. Still, Kingdom Hearts remains controversial among players. Years later, some continue to question the game’s status as a JRPG even as others consider it a genre-defining masterpiece.[3]

Instead of trying to determine the genre status of Kingdom Hearts, this article uses the JRPG as an entry point to examine the game’s Japanese identity through the lens of auteur. With the goal of uncovering how race operates within the game’s production as well as in the globalized Japanese videogame industry, I read Kingdom Hearts as a JRPG masterminded by Nomura, whose auteurist identity became closely aligned with Square’s corporate branding as a JRPG pioneer.[4] In legal terms, Square served as a Disney licensee during the production of Kingdom Hearts, with much of the intellectual property (IP) represented in the game legally owned by Disney. And yet, throughout the development and promotion of Kingdom Hearts, Square deployed several ingenious strategies in line with the company’s ambition to grow its global business, using the Disney brand to bolster its reputation. In the making of Kingdom Hearts, Square was no mere vassal of Disney. Square had greater ambitions, reflected in the high-profile involvement of Nomura in the game’s promotional campaign; he was presented as a visionary game director. On one level, Kingdom Hearts prioritizes the Disney IP (at the expense of Final Fantasy characters), a factor that lends the game an aesthetic that conceals its Japanese origins and hence appears to be at odds with the presentation of Nomura as a Japanese auteur. However, as I argue, Nomura emerged in this context as a highly unconventional auteur—what I call an anti-auteur, one whose personal vision, not to mention his polarizing reputation and pro-corporate image, was in sync with Square’s prioritization of licensed IP from a Western conglomerate. In other words, Kingdom Hearts should be understood as a cultural-industrial paradox: while it inspired doubts about the Japanese-ness of the JRPG genre, it was also widely celebrated as the brainchild of a Japanese auteur. It thus reveals the workings of an industrial structure that deracinates JRPGs to make globally exportable products by detaching them from the race of their developers.

A study of these cultural and industrial processes makes visible the racialized labor of Square, which, while often overshadowed by Disney in fan discourse, was in fact the leading creator in Kingdom Hearts’ development. Through a reading of Nomura’s directorial choices, including his public statements and game designs, this study also reveals his key interventions as an anti-auteur: the ways with which he subverted Disney’s control to fashion a game that aligned with Square’s brand of JRPGs.

This article focuses primarily on the first game in the Kingdom Hearts franchise, especially on the production and design choices that underlie Nomura’s success in maneuvering public opinion to recognize his status as the auteur behind the franchise. In film history, the phenomenon of the auteur is the result of a practice that interprets films not as stand-alone texts but as interconnected through the vision of a director, which in turn allows the audience to derive pleasure from identifying recurrent stylistic and thematic elements utilized by the director. For this reason, film critic Andrew Sarris defines auteur theory as “a pattern theory in constant flux.”[5] Transposing this concept to game studies, the game auteur is a figure whose vision is read through a body of work or oeuvre. By virtue of certain production and design choices, this is precisely how Nomura is constructed in relation to the Kingdom Hearts franchise.

Yet, unlike other game auteurs, whose authorship over their games is usually assumed without debate, Nomura had to actively defend his status as the author of Kingdom Hearts because of the game’s reliance on licensed Disney IP. By making sense of how Nomura defended his authorship of the first Kingdom Hearts while sharing credit with a Western company such as Disney, we can better understand how he fashioned himself as an anti-auteur.

The implications of Nomura’s contested authorial status and Square’s reliance on Disney IP to construct its brand lie in the erasure of minority labor in an industry that often detaches or conceals the race and ethnicity of its workers from the content they produced.[6] The genre of JRPGs remains understudied in the Western-centric field of game studies despite its prevalence in and influence on the global videogame industry.[7] Studies of JRPGs promote a better understanding of how Japanese game developers rely on the absence of pointedly racialized game content to facilitate readily exportable global products. For this reason, JRPGs are vital to our theorization of the racial politics that underlie the labor economies of an increasingly globalized videogame industry.

In what follows, I first present a historical overview of how the JRPG genre was pioneered by Square and its competitor Enix, emphasizing the manga/anime industry’s influence on the genre as well as the notion of auteur within the context of the videogame industry. Next, I situate Kingdom Hearts within a Japanese media landscape undergirded by a strategy to develop export-ready products through racial erasure known as mukokuseki. I subsequently demonstrate the inseparability of Kingdom Hearts’ success as a mukokuseki product from Nomura’s status as a Japanese auteur, or rather anti-auteur: his deviation from the conventions of a game auteur. In the final two sections, I uncover the racialized labor obscured by Kingdom Hearts’ mukokuseki façade by shedding light on the creative agency of Nomura and his team at Square. To this end, I analyze media interviews with Nomura about Kingdom Hearts and perform a close reading of the game’s creative designs. To conclude, I elaborate on the utility of the anti-auteur concept to future game research.

A History of JRPGs

The history of JRPGs arguably began with Dragon Quest (Enix, 1986), which exemplifies the inextricable link between the Japanese videogame industry and manga/anime industry, a major factor that sets the Japanese game industry apart from the Western game industry. According to Sebastian Deterding and José Zagal, “While the first use of the term ‘JRPG’ is difficult to locate precisely, fans, not game developers or marketers, are generally credited with coining the term. . . . Specifically, players noticed that games from Japanese developers afforded less player customizability, often forcing players along pre-determined paths, but provided engaging character development and narrative arcs.”[8] While the American and European early videogame developers in the 1970s and 1980s were usually hobbyist programmers, pioneering game makers in Japan included both computer hobbyists and manga enthusiasts. In their study on cross-sectoral transfer of skills between videogame and other media industries, Hiro Izushi and Yuko Aoyama note that “the sharing of artistic talent between cartoon or animated films and video games in Japan has led to a number of common features” among these Japanese visual media.[9] In fact, Dragon Quest was designed by Yuji Horii, who previously worked in the manga industry, and features characters drawn by famed mangaka (author of manga) Akira Toriyama.

The strong ties between the videogame industry and manga/anime industry in Japan as well as the involvement of mangaka in game production account for why more Japanese game developers are hailed as auteurs and tend to receive more public attention than their Western counterparts. Noted game journalist Chris Kohler states, “In terms of name recognition, the Steven Spielberg of video games [in Japan] is Yuji Horii, who designed an RPG called Dragon Quest for a video game publisher known as Enix.”[10] Before he became a game designer at Enix, Horii was a writer for the influential manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump.[11] While Horii is widely credited as the game creator, Dragon Quest was also shaped by Toriyama and composer Koichi Sugiyama, who elevated the visual and aural appeal of the game. Notably, Toriyama was serializing his career-defining work, Dragon Ball, in the pages of Weekly Shōnen Jump at the time. Hence, the inclusion of game characters designed in Toriyama’s signature art style made Dragon Quest instantly appealing to many manga fans. Horii played a very different role in establishing the game’s reputation. When Dragon Quest proved to be a commercial failure upon its initial release on the Family Computer, or simply Famicom (known as the Nintendo Entertainment System [NES] in North America and Europe), Horii managed to turn sales around by publishing a series of promotional articles in Weekly Shōnen Jump that introduced the concept of JRPG to its readers. Not only did these articles boost sales of Dragon Quest, but they established Horii’s position as one of the first Japanese game auteurs.[12]

While Dragon Quest laid the foundations for the genre, it was the Final Fantasy series that popularized the concept of JRPG for players outside of Japan, bringing global fame to its developer and setting the stage for Square to collaborate with Disney. When Dragon Quest was making its mark on the Japanese videogame industry, Hironobu Sakaguchi was developing an RPG for Famicom at Square, one that he hoped would compete with Dragon Quest. Sakaguchi named the project Final Fantasy because Square was not doing well financially, and he was prepared to quit the job if the game did not perform.[13] To distinguish Final Fantasy from Dragon Quest, Sakaguchi wanted a more “serious” and “adult” feel for his game in terms of the visual design and music; plot-wise, he envisioned an epic storyline with multiple interlocking story threads and unexpected plot twists, in contrast to Dragon Quest’s formulaic save-the-princess narrative.[14] Instead of featuring kawaii (cute) manga-style characters like those of Toriyama, Sakaguchi collaborated with artist Yoshitaka Amano. While not as famed as Toriyama at the time, Amano was known for his stylized watercolor illustrations and garnered a loyal following for the characters he designed for numerous anime, notably the cult hit Tenshi no Tamago (Angel’s Egg, Mamoru Oshii, 1984). For the music, Sakaguchi directed Square’s in-house composer Nobuo Uematsu to “make a contrast to the Dragon Quest series,” which Uematsu responded to by composing music with a sabishii (lonely) vibe, the opposite of the vibrant and upbeat soundtrack Sugiyama created for Dragon Quest.[15] The collaboration between Sakaguchi, Amano, and Uematsu resulted in a game unlike any other Famicom title at the time, setting the tone for its sequels. While it was not a hit, Final Fantasy was financially successful enough for Sakaguchi to stay at Square, where he continued to work on its sequels with Amano and Uematsu for the next decade. Years later, when Final Fantasy VII was released—on January 31, 1997—the game became the first JRPG to break into Western markets, making Final Fantasy a brand name that players outside of Japan consider synonymous with the genre.[16] In fact, the success of the game series in the United States led to the induction of Sakaguchi into the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame in 2000, furthering his fame as a game auteur. The global recognition that Square garnered through the Final Fantasy series elevated the developer as a JRPG pioneer and gave it the leverage to initiate a partnership with Disney.

No subsequent JRPGs developed by Square and Enix matched the enduring popularity of the Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy series—that is, until the release of Kingdom Hearts. Produced shortly before the merger of Square and Enix, Kingdom Hearts became the company’s third flagship franchise. Whereas sequels to Dragon Quest have remained successful in Japan by adhering to its foundational JRPG formula and maximizing their nostalgic appeals—namely, manga aesthetic, medieval fantasy settings, and turn-based combats—the Final Fantasy series is known to be more experimental, especially in terms of cinematic storytelling and high-end visuals. Kingdom Hearts, while built on a combination of JRPG traditions established by its two predecessors, including the use of cinematic cutscenes and anime aesthetic, also innovated the genre by challenging common conceptions of what constituted a JRPG, especially through its incorporation of Disney IP. The game was an instant international hit and became the foundation for a prolific franchise with ten unique titles (excluding ports and remakes) released across multiple platforms, including mobile phone, personal computer, and nine different game consoles. The success of Kingdom Hearts also elevated Nomura to auteur, as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy had with Horii and Sakaguchi, respectively. While its crossover formula is unique (not many developers are in a position to secure a license from Disney), Kingdom Hearts is not an outlier of the genre and in fact exhibits many common JRPG attributes, including an erasure of Japanese-ness.

Kingdom Hearts, the Nationless JRPG

Kingdom Hearts, like many other Japanese games and anime, is an Orientalist product that caters to a global audience by erasing any recognizable Japanese cultural features, including racial markers, from its content. This form of self-Orientalism, premised on the erasure of what Koichi Iwabuchi calls “cultural odor,” which includes the country’s bodily, racial, and ethnic features, was vital to the significant increase of Japan’s capital share as well as cultural presence in the global audiovisual market in the 1990s.[17] By prominently featuring Disney characters and settings, supplemented by cameo appearances from Final Fantasy characters, whose designs are mostly inspired by medieval fantasy, Kingdom Hearts sheds any attributes that might evoke association with Japan as its country of origin.

The strategy to create exportable products devoid of Japanese cultural traits originates from the concept of mukokuseki (without nationality), which first gained traction in the 1970s. As Christine Yano observes, mukokuseki “became the common means for Japanese companies to dodge any negative imaging of cheap, poorly made goods that ‘Made in Japan’ may have held” in a global market dominated by Euro-American countries.[18] In this regard, Kingdom Hearts is similar to the Pokémon franchise, which Tara Fickle identifies as “a ludo-Orientalist artifact not because the original franchise . . . comes from Japan, but because it is at every level informed by the way Japan is perceived by, and how it wishes to be perceived by, the ‘West.’”[19] In other words, the goal of making Japanese products mukokuseki is not to make the consumers forget that these products come from Japan but to trivialize their Japanese origin. The foregrounding of Disney IP in Kingdom Hearts contributes to the game’s mukokuseki strategy.

While marketed as a crossover game that combines the Final Fantasy series with Disney animations, Kingdom Hearts prioritizes Disney properties over those of Final Fantasy to align itself with the Euro-American norms in the globalized videogame market. Notably, most of the game environments or stages are based on settings from Disney animations, not from Final Fantasy. Preferential treatment to Disney characters is also apparent in the game’s storyline, in which the Final Fantasy characters form a scattered diasporic community in a Disney-dominated universe, their homelands having been destroyed by a dark force. While the Final Fantasy characters supposedly come from different lands, they all acknowledge Mickey Mouse, the symbol of the Walt Disney Company, as the King of the Magic Kingdom in the game. Square literally transforms the Final Fantasy characters into nationless figures to incorporate them into the narratives borrowed from Disney animations. Such whitewashing, referred to by Yano as “performing commodity white face,” is characteristic of mukokuseki, which is “very much imbued with Euro-American culture or race” due to the status of Euro-American culture as the unmarked norm throughout much of the world.[20]

Despite the aggressive approach that the company adopted in developing a mukokuseki game stripped of apparent Japanese cultural and racial markers, Square promoted Kingdom Hearts as the creative vision of Nomura, who gave numerous interviews drawing attention to his personal creative process in the making of the game.[21] Nomura was presented publicly as the game’s auteur, having served as the game’s director, concept designer, main character designer, and one of the storyboard designers. Clearly, from Square’s perspective, the production of a mukokuseki game and the promotion of a Japanese as its auteur did not contradict; as I stated earlier, the goal of rendering a product mukokuseki is not to erase but rather trivialize its Japanese origin. As Iwabuchi writes of Pokémon, the game is globally popular because it is designed to make children “perceive Japan as a cool nation [that] creates cool cultural products” despite the franchise’s deliberate minimization of “a tangible, realistic appreciation of ‘Japanese’ lifestyles or ideas.”[22] Similarly, the recognition of Nomura as a Japanese auteur capable of creating a captivating game using Disney IP does not readily translate to admiration for actual Japanese culture, which is absent in Kingdom Hearts. That said, Nomura’s racial and nationality still endows the game with an aura of Japanese-ness.

As a re-creation of Disney based on how a Japanese auteur views Disney, the Japanese-ness of Kingdom Hearts lies not in any visible racial traits in the game but rather in Nomura’s attitude toward Disney IP, which makes itself known in the game as a subtle form of campiness. Camp is a difficult concept to define because it is above all a sensibility. Two of the many definitions of camp given in Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” are especially useful in this context: “Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style . . . of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not” and “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. . . . To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role.”[23] In his examination of game fandom from a queer perspective, Rob Gallagher contends that many Japanese games from the 1990s, including JRPGs such as Final Fantasy VII, exhibit qualities “conducive to precisely the kinds of projective identification, enthused amateurism and felicitous mistranslation that [Eve] Sedgwick identifies with camp, fostering a subculture of Western devotees of Japanese video games.”[24] Kingdom Hearts fits the camp sensibility by reimagining Disney from the perspective of a Japanese auteur—a Japan-ish Disney role-playing game. In an interview for Famitsu Weekly magazine in 2013, Nomura is asked, “Are there modifications to the story [of Kingdom Hearts] to suit overseas fans?” His response is illuminating: “I believe that if the story is interesting, it will be well received; so it isn’t regulated only for specific regions. Though those at Disney said it has a very Japanese sense about it, I guess you could call it ‘Eastern thinking.’ (Laughs).”[25] Although the story of Kingdom Hearts consists of disparate subplots derived from numerous Disney animations and connected by an overall plot that heavily features iconic Disney characters, the staff at Disney still see it as an exotic product of “Eastern thinking” inextricable from its Japanese auteur. That is, Nomura’s reputation, inseparable from his race and nationality, automatically confers on the game a Japan-ish campy aura to non-Japanese players even if Nomura did not deliberately envision the game from a Japanese perspective.

Tetsuya Nomura as Anti-auteur

To understand how the concept of auteur can be applied to game developers, let us revisit its origins in film history. The most widely recognized version of auteurism can be traced back to a March 1948 essay by Alexandre Astruc, who views the camera as caméra-stylo (a metaphorical pen) and hence theorizes film as “a means of writing just as flexible and subtle as written language.”[26] Astruc’s essay inspired a group of French film critics, most notably François Truffaut, to construct the concept of cinéma d’auteur (the film auteur) in the pages of Cahiers du cinéma in the 1950s. These auteurist critics differentiate the run-of-the-mill products of a competent director who has no style from the works of auteurs, a title reserved for a true artist “whose personality was ‘written’ in the film.”[27] In gaming contexts, an auteur—often a director or a designer—can be broadly understood as someone who manifests a signature style in the games they create. While an influential concept in film theory, auteurism has yet to take root in the largely Western field of game studies because the field often overlooks Japanese contexts where game auteurism is much more prominent. Christopher Patterson has written one of the most extensive analyses of game auteurs, in which he contrasts the general invisibility of American developers with the hypervisibility of their Japanese counterparts. Whereas Patterson is interested in “how the authorial function of the auteur opens up alternative ways of understanding games beyond a discourse of player-centered responsibility,” I instead explore the auteur as a valuable industrial construct that tends to decouple game developers from their racial identity for commercial reasons.[28]

Nomura’s career as a Japanese auteur differs significantly from those of his peers in numerous ways—namely his polarizing reputation, reliance on licensed IPs, and pro-corporate persona—making him an atypical auteur or what I refer to as an anti-auteur. First, Nomura is known within Western gaming communities for being a controversial figure who has attracted as many admirers as detractors. The author status, as Michel Foucault notes, occurs not through “the simple attribution of a discourse to an individual” but rather through a “complex process” that includes “projections . . . of our way of handling texts.”[29] In the context of gaming communities, such projections, which manifest most lucidly in online fan discourses, form an important component that sustains the existence of game auteurs and hence an important archive that can be used to read the auteurs and the games they make. Of the innumerable examples on the internet, a forum thread on Kingdom Hearts Insider titled “The Tetsuya Nomura Hate Club,” in which the initiating poster states, “Nomura gives me rage of the Brooklyn variety,” exemplifies the polarizing status of Nomura among Western players and the seemingly irrational negative emotion he engenders in some of his most vocal detractors.[30]

Second, Nomura’s unorthodox auteurship is underscored by his fame as the creative mastermind behind a licensed game franchise. Most auteurs are celebrated for original creations instead of borrowed properties. As Patterson observes in his examination of game authorship, Japanese game auteurs in particular are “known as experimentalists, mavericks, and iconoclasts who upset the corporate, profit-driven atmosphere of despised Western game companies.”[31] Patterson further explains that whereas “Western developers gain little recognition for their work so that game companies can cast blame onto players themselves for a game’s violence and sexual transgressions,” Japanese developers are marketed by the publishers as “auteurs responsible for grandfathering in most gaming genres.”[32] That said, Nomura’s association with a game that relies on properties licensed from one of the biggest American conglomerates runs counter to the common notion of a game auteur in Japan.

Third, Nomura’s pro-corporate image, engendered by his close affiliation with Square Enix, also informs his status as an anti-auteur. Despite their shared JRPG auteurist lineage through Square, Nomura’s and Sakaguchi’s career trajectories are markedly different. Anti-corporate sentiments are often tied to the auteurship of Japanese developers, who often part ways with the publishers that establish their careers to open their own independent studios for the purpose of gaining more creative freedom. Sakaguchi was the executive vice president of Square but resigned shortly after the company’s merger with Enix—a merger occasioned largely by the massive financial loss Square suffered from the commercial failure of the computer-animated film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), directed by Sakaguchi himself. Sakaguchi revealed a decade after his resignation that he “hated Square . . . the whole business part of it” and lamented Square’s obsession with making profits, a tendency he tried to temper at Mistwalker Corporation, a studio he founded after leaving Square Enix.[33] Unlike Sakaguchi, Nomura has maintained a productive working relationship with Square Enix (as of the time of writing) and even plays an increasingly important role in the company’s high-budgeted, blockbuster-scale projects, having recently directed Kingdom Hearts III (2019) and Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020).

Nomura’s unconventional auteurship also contrasts with those of Shigeru Miyamoto and Hideo Kojima, both unquestioned auteurs in mainstream discourses. As auteurs, Miyamoto and Nomura share an uncommon trait—their auteurships are closely associated with the companies they work for. However, unlike Nomura, Miyamoto, who works for Nintendo, does not possess a pro-corporate image; Miyamoto’s route to auteurship is best described as incidental. Miyamoto’s reputation is not defined by his work for Nintendo, at least not in his early career. Nick Paumgarten explains, “Miyamoto has been a superstar in the gaming world for more than two decades, but neither he nor the company seems inclined to exploit his stardom. They contend that the development of a game or a game console is a collaborative effort—that it is indecorous to single out any one contributor, to the exclusion of the others.”[34] Such restraint contrasts sharply with Square’s aggressive marketing of Nomura as a visionary, a process that began with his directorial debut, Kingdom Hearts. For this reason, Miyamoto is seen as an organic auteur who led Nintendo to success, whereas Nomura is perceived as an auteur manufactured by Square Enix in media and fan discourses.

In opposition to Nomura’s brand of corporate auteurship, Kojima is known as a rogue auteur who had a high-profile split with his former longtime employer, Konami. Celebrated as the creator of the Metal Gear series (1987–2015), Kojima calls himself “a creator with an auteurist approach” and is reputed for utilizing “Hollywood-inspired storytelling” in his games due to his adoration of Western film auteurs, including David Lynch, Stanley Kubrick, and Quentin Tarantino.[35] Despite his illustrious, three-decade-long career with Konami, Kojima shocked the industry by falling out with the company in March 2015. While the true reason for their breakup was never revealed, Adrian Chen notes that “[f]ans and sympathetic bloggers filled in the gaps with a narrative that cast Kojima as the victim of a corporation’s soulless quest for profit, only further solidifying his reputation as an auteur.”[36] Kojima’s brand of auteurship, marked by anti-corporate sentiments and deliberate association with Western auteurs, is almost antithetical to that of Nomura, who is known as a spokesman of Square Enix and a flag-bearer of JRPGs.

The figure of anti-auteur embodied by Nomura stands out not merely for its divergence from other auteurs such as Miyamoto and Kojima but also by its ability to reveal the fact that the game auteur is ultimately a capitalist construct that is inseparable from and heavily dependent on corporatism. Miyamoto might be an organic auteur who works as a salaryman for a company known for its family-friendly products, but he is also a high-ranking leader of a multinational conglomerate. Similarly, while Kojima is alleged to be a martyr of corporate greed, he achieved fame as a Konami employee and continues to seek corporate sponsorship, most recently from Sony, even after he left Konami to establish his own studio.[37] Instead of disavowing his corporate roots as Miyamoto and Kojima have, Nomura leans into his corporate backing from Square Enix and Disney. Like an anti-hero, Nomura is not afraid to embrace a pro-corporate image usually frowned upon in gaming communities. Yet Nomura’s brazen personification of an anti-auteur also reproduces corporate structures, just as much as those of other game auteurs. Indeed, this is precisely what we can learn from Nomura’s public maneuvers as tensions rose between Square Enix and Disney in the making of Kingdom Hearts.

The Tug of War between Square Enix and Disney

When we consider the tensions between Disney and Square Enix—which stem from the power imbalance inherent in their licensor-licensee relationship—the knockout success of Kingdom Hearts, rare for Disney-licensed games, is all the more remarkable. Mia Consalvo’s research on the business culture of Square Enix shows that even before the merger of Square and Enix, “both companies began to consider audiences external to Japan for their games” and “did valuable work in continuing to promote the JRPG genre as it began to travel outside Japan and became known as a distinctive kind of videogame.”[38] This outward-looking propensity that resulted from Square’s global business model could be tied to the “graying of Japan,” as Japan-based game companies faced increasing pressure to expand their international business in the early twenty-first century due to the nation’s aging population and declining birth rate.[39] Hence, the tremendous success of Kingdom Hearts when it was released in North America as a stand-alone title was a fortuitous accomplishment for Square, as it was for Disney. As Rob Fahey remarks, “When Disney has found success with games in recent years, it’s largely only been in partnerships which mix its IPs into other companies’ formulae,” citing the Kingdom Hearts franchise as a key example.[40] Fahey adds that “the licensing approach seems to result in weaker games—perhaps because the inevitable bureaucratic overhead introduced by . . . giant corporations leaning over the developers’ shoulders is a significant burden on creativity and speed.” Taking the limitations of the licensing approach into consideration, the acclaim Kingdom Hearts received attests to Square’s expertise as a game developer capable of elevating, rather than simply reproducing, Disney’s IP.

With Kingdom Hearts, Square was intent on making its creative agency clear to its partner Disney by heavily featuring Nomura in the promotional campaign for the game. Nomura in turn used interviews to assert his creative vision. In fact, despite Disney’s dominance as one of the biggest entertainment conglomerates in the world, Nomura insisted on his autonomy since the preproduction of Kingdom Hearts, crafting an origin story in which he defied his subordinate position at a Disney office requesting to use its IP. In a comprehensive interview with late Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata, Nomura detailed how he first conceived the basic premise of Kingdom Hearts.[41] When Nomura was working on Final Fantasy VII, Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996) was released. Being the first Super Mario Bros. game to utilize 3D graphics, Super Mario 64 enables the players to roam around in fully 3D environments, which left a huge impact on Nomura. When Nomura told his colleagues that he would like to make a game like Super Mario 64, they remarked that it would be impossible for him to compete with Mario using new characters unless his game also features characters as famous as Disney’s. This conversation stayed with Nomura and formed the seed of Kingdom Hearts. Years later, Nomura went to Disney’s office for a meeting with the vision of a game situated within a 3D space. Disney’s staff presented Nomura with various ideas, but Nomura interrupted their presentation to sell them on his initial concept for Kingdom Hearts: “all-new characters going on a journey through the worlds inhabited by Disney characters,” an experience akin to going to a Disney theme park.[42] After several meetings, Disney eventually greenlighted Nomura’s proposal. This origin story, as told from Nomura’s perspective, emphasizes his and, by extension, Square’s autonomy in the meetings with Disney in which he successfully fought for his ideal vision of Kingdom Hearts.

Notwithstanding Nomura’s instrumental role in the conception of Kingdom Hearts, all original IP related to Kingdom Hearts, including the protagonist Sora, legally belongs to Disney, a fact that seems to mitigate Nomura’s claim to authorship. A press release for the 2001 Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) prior to the release of the game states, “Making their debut in ‘Kingdom Hearts,’ the new Disney characters—Sora, Riku, Kairi, and the Heartless—are designed by director and character designer Tetsuya Nomura, best known for his creations in Square’s Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII [(1999)] games.”[43] While the press release invokes Nomura’s fame as a character designer, it also makes clear that those characters belong to Disney and not Square. As Nomura confessed at the time, “I love Sora, but it’s with a broken heart.” His work on the character was “not unlike a parent giving a child up for adoption,” for he had “no control over Sora or any other original characters appearing in Kingdom Hearts [because] the contract between Square Enix and Disney gives almost full control of the Kingdom Hearts property over to Disney.”[44] Nomura’s admission of his lack of control over Sora and other IP related to the game detracts from his claim to auteurship.

Despite its status as a licensee, Square was given a relatively huge amount of creative freedom in developing Kingdom Hearts.[45] Disney, while retaining its creative veto over any decisions involving their IP, merely served in a consulting role in the development of Kingdom Hearts, signifying its trust in Square to produce a quality game that adheres to Disney’s high standards. Certainly, as a licensee, Square had less creative control over the game and less time to focus on game development than it would have had if it were to work only with properties that it owned or created from scratch.[46] However, at an open Q&A session during the 2004 Tokyo Game Show, Nomura remarked that the Disney representatives “don’t really see [the game] in development at all,” which is surprising given that Disney is known to be very strict when it comes to regulating the usage of their IP.[47] By revealing Disney’s lack of interference despite their contractual power, Nomura reasserted his creative autonomy in developing Kingdom Hearts and that the game was as much a Square product as it was a Disney one. In addition, Nomura stated in a 2003 interview that “there weren’t any big restrictions or a set of guidelines [given to us by Disney] . . . , the only thing we were careful of doing was staying within the characters’ established roles and what kind of dialog these characters should have.”[48] Once again, the auteurist image Nomura sought to project was a complicated one. On the one hand, he stresses Square’s autonomy from Disney. On the other, he makes clear that his creative freedom as an auteur was restricted during the game’s development.

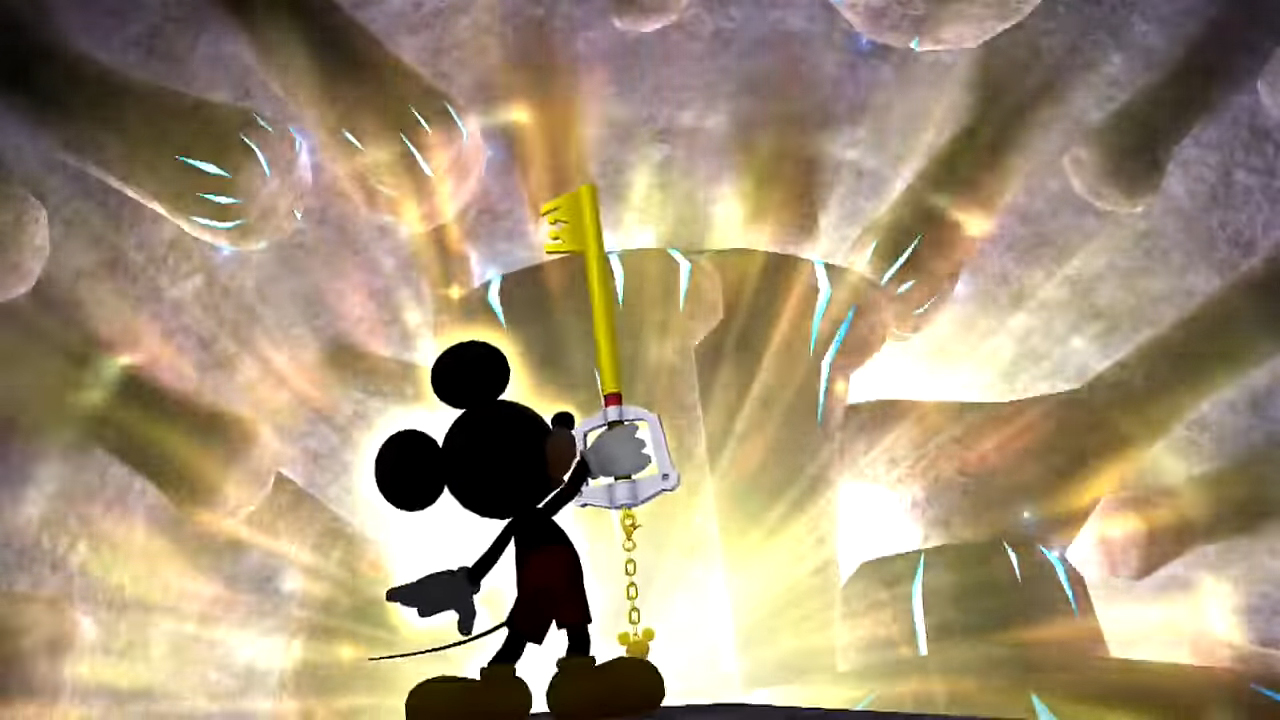

Disney’s guidelines to Square for Kingdom Hearts mainly concerned the use of its characters, notably Mickey Mouse, the company’s most iconic character. Character model director Tomohiro Kayano notes that “Donald was allowed to carry a stick and Goofy has a shield, but [Disney] did not permit [Square] to let them carry swords or anything like that.”[49] More pointedly, Square struggled to get Disney’s approval to feature Mickey Mouse in the game. Square was able to allude to Mickey Mouse (as “King Mickey”) throughout Kingdom Hearts, but it could only feature the character visually in one cutscene. Disney even imposed restrictions in how Mickey Mouse could appear in that cutscene; he is shown facing away from the game camera and heavily shadowed (see Figure 1). Nomura revealed in 2019 the specific reason for Mickey Mouse’s brief and obscured appearance in the first game: “At the same time [as Square was developing Kingdom Hearts], another company was releasing a game that had to do with Mickey, so though we were denied his usage, we persisted and eventually got [the permission from Disney that] ‘as long as you only have one scene, from far away, as a silhouette, with him waving his hand or something.’”[50] While Square Enix eventually made Mickey Mouse a prominent character in the game’s sequel—indeed, one of the prerequisites for Square Enix to begin the development of Kingdom Hearts II (2005), was to get Disney’s permission “to give Mickey more spotlight” in the game—this right had to be earned.[51] Ultimately, Square had to operate within the boundaries set by Disney no matter how much creative autonomy Nomura claimed for himself or Square. That said, Nomura’s stance on Square’s agency despite the power imbalance in its relationship with Disney is not entirely misleading because Square indeed occupied an especially important position among Disney’s game licensees at the time.

Unlike most of Disney’s licensees, Square was a high-profile developer that Disney promoted as their collaborator with great fanfare, a strategy that benefited Disney in various ways. At the start of the twenty-first century, as Disney began to shift strategies for its game division, Disney Interactive, toward the licensing model (mainly to reduce risks and expenses related to game development), they also confronted how poor these externally developed licensed projects could turn out to be; Kingdom Hearts represents one of the few successful licensed games issued by Disney Interactive at the time.[52] Graham Hopper, the then-president of Disney Interactive, remarked that it was difficult to control the quality of licensed products due to the uneven efforts of their licensees, but he singled out Square for its exceptional caliber: “Because some licensees, like Square, invest significantly in quality and produce fantastic product, and other licensees, not so much.”[53] In fact, Disney had chosen to work with Square in order to leverage Square’s global fame as the developer of Final Fantasy to expand the Disney brand within the videogame industry, evidenced by the manner in which Disney referenced Square in promotional materials. In Disney’s 2001 E3 press release, Hopper’s predecessor Jan Smith described Square as “one of the world’s leading interactive entertainment companies” that they were “working in alliance with.”[54] In addition, Disney’s then-CEO Michael Eisner invoked Square as a business partner in his “Letter to Shareholders” for Disney’s Annual Report 2001 to validate Disney’s venture into the interactive game business: “we are currently working on a game called Kingdom Hearts, which Square Soft of Japan is developing with us.”[55] Instead of treating Square as a licensee who works for them, Disney was publicizing Square as a co-equal partner whom they are working in conjunction with. Furthermore, Hopper divulged that the success of Kingdom Hearts, the idea of which was initially considered by some Disney staff as an “abomination,” challenged those at Disney Interactive to take creative risks that would not have been possible before the release of the game.[56] This led to the creation of the internally developed Epic Mickey (Junction Point Studios, 2010), a Wii game that rebrands Mickey Mouse as an adventurous hero who has to face off against other classic Disney cartoon characters.

Disney was not the sole benefactor of the partnership with Square; Square also had much to gain from the immense success of Kingdom Hearts. The company profited handsomely, critically and financially. Garnering near unanimous acclaim from game critics upon release, Kingdom Hearts further elevated the status of Square as the leading JRPG developer.[57] In their review for GamePro, Fennec Fox entreats players to “please don’t let the Disney logo scare you away from Kingdom Hearts,” a reference to Disney’s infamous association with bland licensed edutainment games, and asserts that “fortunately for gamers, Square has taken 75 years of Disney history, added a few pages from its own library, and created what’s easily the best action/RPG for the PS2.”[58] David Smith of IGN similarly mentions the initial bafflement of many players to “a Square-styled fantasy adventure starring almost nothing but Disney cartoon characters” but proclaims that Square had successfully utilized “the wealth of [Disney] characters available and [applied] industry-leading production values to create an amazing entertainment.”[59] The critical acclaim Kingdom Hearts received was matched by an equally towering sales figure accrued in a relatively short period: the game sold one million copies in the United States six months after its stateside release and a combined three million copies worldwide one year after its initial Japanese release, boosting Square’s fiscal earnings in 2002.[60]

Despite this shared success, the game was more highly valued by Square than Disney, the owner of the IP. While Square and Disney never revealed their revenue sharing model to the public, we can safely assume that Square retained a significant portion of the profit that came from the sales of Kingdom Hearts based on impact the game had on Square’s 2002 fiscal earnings. Square’s strong financial showing for the 2002 fiscal year—a consolidated net profit of 11.5 billion yen adjusted from an earlier projection of 4.8 billion yen (this contrasts with the loss of 16.6 billion yen in the previous fiscal year)—was credited to the strong performance of Kingdom Hearts in North America, selling 1.5 million units in the region that year, far exceeding the initial projected sales.[61] Having said that, the Kingdom Hearts merchandise sold by Square Enix can scarcely be found in Disney retail spaces. Similarly, Kingdom Hearts has minimal presence in Disney theme parks; at the time of writing, none of the amusement rides in any of the Disney theme parks around the world are based on the game. All in all, the status of Kingdom Hearts as one of Square’s flagship titles as compared to the ancillary position the game held in Disney’s product line makes clear that Kingdom Hearts was, and remains, a more important IP to Square than it has ever been to Disney.

The Racialized Labor that Disneyfied Kingdom Hearts

While Disney’s involvement in Kingdom Hearts often obscures the racialized labor of a mainly Japanese creative team that developed the game, this issue can be rectified by better understanding the ingenuity with which Nomura and his team recontextualized Disney’s IP and theme park designs for the game. Crucial here are the environment designs of Disney theme parks and animations that Square borrows in executing the level designs (i.e., game environment design) for Kingdom Hearts. The universe of Kingdom Hearts consists of numerous levels—referred to in-game as worlds, each themed after a specific Disney animation, like those for Disneyland’s Fantasyland and Frontierland—that the player must progress through successively. These worlds are rendered visually like planets that exist within the same galaxy on the master map of Kingdom Hearts (see Figure 2). The outer-space imagery is reinforced by the mode of transportation, the spaceship-like Gummi Ship that the player must pilot through a shooting mini game to travel from one world to another.[62] Notwithstanding the Disneyland-like designs of Kingdom Hearts, the creativity with which Nomura and his team has repurposed Disney’s designs reaffirms Square’s status as an experienced developer able to construct an enjoyable game out of a multitude of IP.

Nomura faced a challenge in creating virtual simulacra of the settings from Disney animations; the settings needed to present a seemingly seamless 3D space that could be instantly identified as Disney-esque came from the disjointed 2D environment designs used in the animations. One of the methods Nomura utilized to resolve this issue was to situate iconic Disney fictional landmarks within the worlds of Kingdom Hearts so that players can immediately associate these worlds with the animations these landmarks originally appeared in. Just as each Disney theme park has a central landmark, such as the Sleeping Beauty Castle at Disneyland and the Cinderella Castle at Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland, Nomura also marks each world in Kingdom Hearts with an iconic landmark, usually of a grand scale, such as the Sultan’s Palace from Aladdin (John Musker and Ron Clements, 1992) and King Triton’s Palace in Atlantica from The Little Mermaid (John Musker and Ron Clements, 1989). These landmarks, as termed by Walt Disney, are “wienies,” which signify “the magnet, or marquee, that architects and urban planners use to attract and then disperse pedestrian mobs in a variety of directions.”[63] Each Disney theme park has a castle as its wienie because Disney believes that the “lack of visual centrality made other theme parks . . . physically tiresome and psychologically alienating.”[64] Unlike the castles in Disney theme parks, however, the virtual wienies in Kingdom Hearts are mostly not explorable due to the additional resources and time needed to construct the interiors of such massive landmarks. Nevertheless, if the function of a wienie is to be a vertical landmark around which the pedestrians can orient themselves, then these in-game, view-only wienies are equally capable of fulfilling that function.

In addition to recreating the wienies and other notable locations that appear in Disney animations, Nomura and his team needed to create new explorable game environments to fill in the gaps created by spaces not depicted in the animations. Given the medium specificities of animation, Disney animators need only to draw the backgrounds within the designated shots, which means they can leave out environments not shown and rely on the techniques of continuity editing to create an illusion of environmental continuity. However, to fulfill Nomura’s Mario 64–inspired vision, his team needed to create a continuous 3D environment within which the players can roam about with their avatar character as well as a fluid in-game camera that follows the movement of the player-avatar. This means that the developers at Square, unlike the Disney animators, had to consign much of the control of the in-game camera to the player (except during the cinematic cutscenes) while still creating spaces that conform to the aesthetics of Disney animations to give players a sense of aesthetic unity.

The inventive extension of Disney animation settings into fully fleshed-out 3D spaces by Nomura and his team in Kingdom Hearts is best demonstrated by the designs of the Monstro level. The inside of a monstrous sperm whale named Monstro is but one of the settings in Pinocchio (Ben Sharpsteen and Hamilton Luske, 1940) and only appears briefly toward the end of the film. However, in Kingdom Hearts, the world themed after Pinocchio takes place entirely within the inside of the creature Monstro. While the creature’s mouth, where Pinocchio’s maker Geppetto is trapped, is the only inner part of Monstro that is portrayed in the 1940 animation, the player of Kingdom Hearts gets to explore multiple body parts of the sea monster not depicted in the animation, including its bowels, throat, and stomach (which are also literally the names of the areas in the Monstro level). The mouth area of Monstro, colored primarily in brown and salmon red, faithfully follows the grim aesthetic of Monstro’s mouth in the film and even features a re-creation of Geppetto’s wooden boat (see Figure 3). The game-original inner parts of Monstro, however, are areas enclosed by variously colored surfaces, but largely within a blue and purple color scheme (see Figure 4). These surfaces are patterned with cell-like irregular circles, which give them a more cartoonish appeal befitting the overall tone of Kingdom Hearts. These surfaces are uneven but rounded in a fleshy way that makes them seem like a plausible extension of Monstro’s mouth, creating a sense of aesthetic unity. Such aesthetic unity coheres the fragmented in-game environments, which are separated by short loading times every time the player moves from one map to another, and thus sustains the fantasy of a cohesive Disney realm.

In addition to Disneyfying the game environments to exploit the appeal of the Disney properties, Nomura also “de-Japanizes” the character designs of Kingdom Hearts to make them appear mukokuseki, notably the protagonist Sora. While Nomura preserves most of the original designs of Disney characters in Kingdom Hearts (save a few new costumes), he creates new characters and redesigns the Final Fantasy characters for the game in super-deformed anime style to match Disney’s cartoon aesthetic. Despite the wide range of anime aesthetics, anime-styled characters tend to have unrealistic physical features and appear racially ambiguous, which aligns with the mukokuseki strategy.[65] In Kingdom Hearts, this aesthetic is exemplified by the design of Sora (see Figure 5). Visually, Sora sports an excessively spiky brunette hairstyle and huge blue eyes on a disproportionately large head. The colors of Sora’s hair and eyes resemble those of a Caucasian, and yet the anime aesthetic he is depicted in is unmistakably associated with Japan. Moreover, Sora wears commonplace modern attire, including a black-and-white zip-up hoodie above a red zip-up romper (characteristic of Nomura, who is known for his fondness for zippers) as well as a pair of yellow sneakers, all of which seem culturally neutral. This is not to say that such garments are devoid of specific cultural origins, but they are so commonly worn by people throughout the modern world in various contexts that they are now perceived by most as culturally nonspecific. For example, hoodies are practical clothing that could be traced back to the 1930s when Champion first created them for laborers in the frozen warehouses in upstate New York.[66] As an amalgamation of design choices that subtly embrace Caucasian physical traits and American apparel culture behind a Japanese aesthetic veneer, Sora embodies Yano’s concept of performative commodity white face.

Sora’s racial ambiguity and apparent lack of cultural markers enable him to act as a blank slate on which the players can readily impose their cultural backgrounds. A concept central to JRPG is that of “becoming the main character,” which Horii proposed when designing Dragon Quest.[67] That is, by gaining new experiences and growing stronger through the main character, the players will increasingly empathize with and grow into the main character as they progress through the game. Crucially, Walt Disney had a similar concept in mind when creating the rides for Disneyland. Disney elected to downplay depictions of the main characters featured in the rides he designed “to allow children to ‘step into’ . . . their favorite animated films” and “‘become’ Snow White or Peter Pan,” for example.[68] In the plot of Kingdom Hearts, Sora is depicted as an energetic prepubescent boy with a simple backstory (although the backstory revolving Sora turns increasingly convoluted as the series expands). Sora grows up on Destiny Islands with no knowledge of the outside world until he is displaced from his hometown by the force of darkness in the prologue of the game. The players subsequently learn more about the various worlds of Kingdom Hearts along with and through Sora as he is forced to go on a journey after the disappearance of Destiny Islands, separating him from his friends. Using Sora, a mukokuseki character designed from scratch instead of any pre-existing characters from Disney animations or the Final Fantasy series, Kingdom Hearts offers a role free of preconceptions that any player can grow into as they progress through the game.

Conclusion

To examine the complexity with which race operates as a fundamental but strategically invisible element in JRPGs and the Japanese videogame industry in general, I have demonstrated how the success of Kingdom Hearts was inseparable from Nomura’s authorship and premised on a form of Orientalism based on racial erasure known as mukokuseki. Understanding how Kingdom Hearts conformed to or deviated from the traditions and conventions of the JRPG genre, which Square helped establish, enables us to understand how Square (now Square Enix) has remained a leading developer of JRPGs. It has done so by continually refining the formula of JRPGs that it pioneered in the 1980s through Final Fantasy. Furthermore, the Nomura-centered marketing campaign of Kingdom Hearts that Square mounted under the shadow of Disney helps us fully grasp Nomura’s unorthodox auteurship, one which complicates his Japanese auteurist lineage due to its inextricability from licensed Western IP. In other words, a deeper comprehension of JRPG conventions and game auteurist traditions reveals the integral functions of race, despite its intentionally minimized presence in games within the genre, to the global success of the Japanese game industry.

Since the first Kingdom Hearts, Nomura’s infamy as an anti-auteur has grown steadily with each new release in the increasingly successful franchise. Nomura’s leverage as a game developer with both Square and Disney surges in tandem with his fame, giving him more autonomy to develop the franchise as he sees fit. A vocal segment of the franchise’s fans views Nomura’s autonomy as excessive and hence blames him for the franchise’s many flaws. One of the main complaints of Nomura’s detractors is the progressively more complicated and inscrutable overarching plot of the franchise, a significant part of which is told through numerous spinoffs during the long fourteen-year interval between the releases of Kingdom Hearts II in 2005 and Kingdom Hearts III in 2019—an interval that frustrated many fans. An illuminating observation concerning Nomura’s autonomy in relation to the limitations many creators face in a corporate environment is made by Göran Isacson in the comments section of a Siliconera article about the launch of Kingdom Hearts: Dark Road (Square Enix, 2020), which Nomura claimed to be a project based on a once shelved idea: “Nomura, through whatever twisted configuration of fate put him in charge of this franchise, somehow got into the position where he doesn’t have to kill SHIT. Like the most indulgent fan-fic author he, unburdened by limits of what needs to sell or what is appropriate and following only his own whims, will show you EVERYTHING . . . and until the day Kingdom Hearts stop selling there is not one goddamn thing any of us can do to stop him. And I can’t decide whether to be awed or dismayed about it.”[69] This perception of Nomura’s autonomy, regardless of its veracity, is inextricable from his seemingly profit-focused, pro-corporate image. Furthermore, Nomura allegedly told Disney that he would not develop Kingdom Hearts III if he could not use Pixar studio’s IP.[70] Disney’s acquiescence led to his growing reliance on Disney IPs, culminating in the complete absence of Final Fantasy characters in Kingdom Hearts III.[71] All in all, the high level of autonomy possessed by Nomura, which is unusual in a corporate environment, is seen as a result of Nomura’s pro-corporate persona and amplifies his reputation among the gaming communities as an anti-auteur who depends on licensed IP.

In exploring how the concept of anti-auteur could prove relevant to future directions of the game studies field, I propose that the utility of the anti-auteur concept lies in its ability to reveal the problematic nature of the auteur as an industrial construct that tends to disconnect the product from the race of its developers as well as to obscure the labor of below-the-line workers. An anti-auteur’s willingness to embrace rather than shy away from their corporate roots makes plain the capitalist structure needed to support an auteur at the expense of the visibility of other developers, most of whom only get recognition when their names appear for a fleeting moment in the end credits. In this sense, an anti-auteur compels game scholars to study auteurs critically instead of treating the auteur as an unproblematic category of analysis. On a broader level, such criticality also encourages the gaming communities to demand more accountability from above-the-line workers and corporate leaders. The lack of accountability that results from the adulation of genius creators and the studios they lead has led to the proliferation of toxic working environments, accentuated in the Western context by the #MeToo movement in Hollywood and the labor issues within the videogame industry that have made headlines in recent years.[72] By exposing what most auteurs are inclined to hide, the anti-auteur disrupts the status quo that enables the game industry to exploit its workers, especially people of color, even if that anti-auteur is part of the system that perpetuates the issue.

I would like to thank former JCMS Co-editor of Outreach and Equity TreaAndrea M. Russworm for mentoring me through the developmental process of this article as part of the JCMS Publishing Initiative.

“So is Kingdom Hearts considered a JRPG or what?,” GameFAQs forum, accessed August 15, 2023, https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/boards/927750-playstation-3/60257196; “so is kingdom hearts not a JRPG,” IGNboards forum, September 23, 2014, accessed August 15, 2023, https://www.ignboards.com/threads/so-is-kingdom-hearts-not-a-jrpg.454235863; and “Poll: are the kingdom hearts games jrpgs?,” The Escapist forum, accessed August 15, 2023, https://forums.escapistmagazine.com/threads/poll-are-the-kingdom-hearts-games-jrpgs.180878/. ↑

Square Enix, “Kingdom Hearts II Achieves Million-Unit Sales Mark in North America in Four Weeks,” press release, May 2, 2006, http://release.square-enix.com/na/2006/05/kingdom_hearts_ii_achieves_mil.html; and “Kingdom Hearts Series Ships Over 10 Million Worldwide,” GamesIndustry.biz, February 7, 2007, https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/kingdom-hearts-series-ships-over-10-million-worldwide. ↑

Kyle Boyd, “Popularity of Kingdom Hearts and How It Impacted the JRPG Genre,” Medium, February 20, 2019, https://medium.com/@kaboyd/popularity-of-kingdom-hearts-and-how-it-impacted-the-jrpg-genre-a91bbf4b267. ↑

To clarify, the first title of the game franchise is the sole focus of this article because of the game's status as the origin of the collaboration between Square and Disney and thus best represents the foundation of the franchise as envisioned by Nomura and illustrates the first contact between the two companies uninfluenced by the franchise's future success. ↑

Andrew Sarris, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” in Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, 4th ed., ed. Gerald Mast, Marshall Cohen, and Leo Braudy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 587. ↑

Patterson notes that the videogame industry often “stresses the neutrality of its products by offering little visibility to its designers” to abdicate any responsibility for any controversial images. Christopher B. Patterson, Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games (New York: New York University Press, 2020), 82. ↑

I would like to acknowledge two recent notable contributions to Japanese game studies relevant to this article (on the JRPG genre and Kingdom Hearts respectively), which I was unable to engage with in depth due to the timing of publication. See Rachael Hutchinson and Jérémie Pelletier-Gagnon, eds., Japanese Role-Playing Games: Genre, Representation, and Liminality in the JRPG (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2022); and Dean Bowman and James McLean, eds., “Charting the Kingdoms Between: Building Transmedia Universes and Transnational Audiences in the Kingdom Hearts Franchise,” special issue, Loading: The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association 15, no. 25 (August 2022). ↑

Douglas Schules, Jon Peterson, and Martin Picard, "Single-Player Computer Role-Playing Games," in Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, ed. José P. Zagal and Sebastian Deterding (London: Routledge, 2018), 107-129. [NOTE: This article was updated on February 12, 2024 to correct the reference in this citation. The original citation incorrectly referenced Sebastian Deterding and José P. Zagal, foreword to Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, ed. José P. Zagal and Sebastian Deterding (New York: Routledge, 2018), 114.] ↑

Hiro Izushi and Yuko Aoyama, “Industry Evolution and Cross-Sectoral Skill Transfers: A Comparative Analysis of the Video Game Industry in Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38, no. 10 (October 2006): 1848, https://doi.org/10.1068/a37205. ↑

Chris Kohler, Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life, rev. ed. (Mineola: Dover Publications, 2016), 77. ↑

Yuji Horii, “Life Is Your Very Own Role-Playing Game: Interview with Dragon Quest Creator Yuji Horii (Part 2),” interview by Waseda University Students, Waseda Weekly, May 16, 2017, https://www.waseda.jp/inst/weekly/feature-en/2017/05/16/25797/. ↑

Kohler, Power-Up, 80. ↑

Ollie Barder, “Hironobu Sakaguchi Talks about His Admiration for ‘Dragon Quest’ and Upcoming Projects,” Forbes, June 29, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/olliebarder/2017/06/29/hironobu-sakaguchi-talks-about-his-admiration-for-dragon-quest-and-upcoming-projects/#5d6554e015b5. ↑

Kohler, Power-Up, 87. ↑

From the liner notes to Nobuo Uematsu’s CD Final Fantasy VII Reunion Tracks (Square Enix, 1997); a translation is found at http://www.ffmusic.info/ff7reunionliner.html. ↑

Final Fantasy VII sold one million units in the United States in about three months, whereas the US sales of its predecessor, Final Fantasy VI, at that point were only four hundred thousand units. Matt Leone, “Final Fantasy 7: An Oral History,” Polygon, January 9, 2017, https://www.polygon.com/a/final-fantasy-7. ↑

Koichi Iwabuchi, Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 28–29. ↑

Christine R. Yano, Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek across the Pacific (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 16. ↑

Tara Fickle, The Race Card: From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 145. ↑

Yano, Pink Globalization, 15–17. ↑

Nomura has given more interviews in Japanese than in English (via translator), but many of his Japanese interviews were translated by fans into English as well. ↑

Iwabuchi, Recentering Globalization, 34. ↑

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’” in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Dell Publishing, 1966), 279–280. ↑

Rob Gallagher, “From Camp to Kitsch: A Queer Eye on Console Fandom,” GAME: The Italian Journal of Game Studies 3 (2014): 40, https://www.gamejournal.it/3_gallagher/. ↑

Translation of Famitsu Weekly interview with Tetsuya Nomura accessed at Kingdom Hearts Insider, published January 2, 2012, https://www.khinsider.com/news/Famitsu-Weekly-Interview-July-2011-2111. ↑

Alexandre Astruc, “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La caméra-stylo,” in The New Wave: Critical Landmarks, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), 18. ↑

John Caughie, introduction to Theories of Authorship, ed. John Caughie (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981), 9. ↑

Patterson, Open World Empire, 88. ↑

Michel Foucault, “What Is an Author?,” in Caughie, Theories of Authorship, 286. ↑

“The Tetsuya Nomura Hate Club,” Kingdom Hearts Insider, March 23, 2010, https://www.khinsider.com/forums/index.php?threads/the-tetsuya-nomura-hate-club.146917. A Google search of “Tetsuya Nomura hate” brings up numerous other forum discussion posts initiated by players who questioned the seemingly irrational hate many members in the gaming communities have directed at Nomura. ↑

Patterson, Open World Empire, 85. ↑

Patterson, 85. ↑

Mike Suszek, “Final Fantasy Creator Sees Mobile Success in Download Numbers,” Engadget, September 8, 2014, https://www.engadget.com/2014-09-08-final-fantasy-creator-sees-mobile-success-in-download-numbers.html. ↑

Nick Paumgarten, “Master of Play: The Many Worlds of a Video-Game Artist,” New Yorker, December 12, 2010, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/12/20/master-of-play. ↑

Tim Biggs, “Famed Designer Hideo Kojima on Auteur Video Games and Going Independent,” Sydney Morning Herald, February 2, 2017, https://www.smh.com.au/technology/famed-designer-hideo-kojima-on-auteur-video-games-and-going-independent-20170202-gu3n22.html. ↑

Adrian Chen, “Hideo Kojima’s Strange, Unforgettable Video-Game Worlds,” New York Times Magazine, March 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/03/magazine/hideo-kojima-death-stranding-video-game.html. ↑

Sony Computer Entertainment, “Sony Computer Entertainment Enters into an Agreement with Kojima Productions,” news release, December 16, 2015, https://www.sie.com/en/corporate/release/2015/151216.html. ↑

Mia Consalvo, Atari to Zelda: Japan’s Videogames in Global Contexts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 110. ↑

Mia Consalvo, “Convergence and Globalization in the Japanese Videogame Industry,” Cinema Journal 48, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 138, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20484485. ↑

Rob Fahey, “When Will Disney Get Back into Video Games?,” GamesIndustry.biz, July 5, 2019, https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2019-07-05-when-will-disney-get-back-into-games-opinion. ↑

Tetsuya Nomura, “Kingdom Hearts 3D [Dream Drop Distance],” interview by Satoru Iwata, Itawa Asks, vol. 12, April 2012, https://iwataasks.nintendo.com/interviews/3ds/creators/11/1. ↑

Nomura, “Kingdom Hearts 3D.” ↑

“Disney Interactive and Square Team Up for RPG!,” 2001 E3 Video Game Industry Reports, Digital Media FX, May 17, 2001, available at https://www.khdatabase.com/Archive:Disney_Interactive_and_Square_Join_Forces_to_Create_Epic_Role-Playing_Game_for_PlayStation_2_Computer_Entertainment_System. ↑

“Kingdom Hearts II: Nomura Press Conference,” Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine, 2004, accessed at Kingdom Hearts Ultimania, http://www.kh2.co.uk/website/interviews/opm. ↑

Anoop Gantayat, “TGS 2004: Tetsuya Nomura Q&A,” IGN, September 23, 2004, https://www.ign.com/articles/2004/09/23/tgs-2004-tetsuya-nomura-qa. ↑

For the basics of third-party licensing for game developers, see Mona Ibrahim, “Analysis: Licensing Third Party IP for Your Game—Where to Start?,” Game Developer, June 30, 2010, https://www.gamedeveloper.com/pc/analysis-licensing-third-party-ip-for-your-game—-where-to-start-. ↑

Gantayat, “TGS 2004.” ↑

Tetsuya Nomura, “Tetsuya Nomura on the ‘Kingdom Hearts’ Sequels,” interview by X-Play staff, TechTV, October 27, 2003, available at https://www.khinsider.com/news/TechTV-Interview-with-Nomura-43. ↑

Disney permits its characters to execute fantastical violence through magical power but strictly forbids Square to associate them with any brutality caused by objects that resemble real weapons, such as the huge sword carried by Cloud from Final Fantasy VII. Dan Winters et al., “The Making of Kingdom Hearts Pt 1 (PS2),” MineTaker, December 31, 2008, YouTube video, 8:13, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZeZ4ariFYm8. ↑

Translation of Kingdom Hearts III Ultimania’s (2019) main Nomura interview accessed at Kingdom Hearts Insider, published March 12, 2019, https://www.khinsider.com/news/Kingdom-Hearts-3-Ultimania-Main-Nomura-Interview-Translated-14763. ↑

Translation of Kingdom Hearts II Ultimania’s (2005) main Nomura interview, accessed at Kingdom Hearts Insider, published May 5, 2012, https://www.khinsider.com/news/Kingdom-Hearts-II-Ultimania-Main-Nomura-Interview-2553. ↑

Willie Clark, “Disney’s Many, Many Attempts at Figuring Out the Game Industry,” Polygon, August 18, 2016, https://www.polygon.com/2016/8/18/12514296/disney-game-industry-history. ↑

Clark. ↑

“Disney Interactive and Square” (emphasis added). ↑

The Walt Disney Company and Subsidiaries, Annual Report 2001, 7 (emphasis added), https://www.thewaltdisneycompany.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2001-Annual-Report.pdf. ↑

Stephen Totilo, “Thank Kingdom Hearts for Epic Mickey,” Kotaku, February 18, 2010, https://kotaku.com/thank-kingdom-hearts-for-epic-mickey-5474368. ↑

The game has a favorable weighted mean score of 85 on Metacritic, accessed April 27, 2020, https://www.metacritic.com/game/playstation-2/kingdom-hearts. ↑

Fennec Fox, “Kingdom Hearts,” GamePro, September 30, 2002, accessed September 1, 2020, http://www.gamepro.com/article/reviews/26235/kingdom-hearts, archived at Wayback Machine. ↑

David Smith, “Kingdom Hearts,” IGN, updated November 24, 2018, https://ps2.ign.com/articles/371/371125p1.html. ↑

Dom Ex Machina, “Kingdom Hearts Sold How Many?!” GamePro, April 30, 2003, accessed September 1, 2020, http://www.gamepro.com/article/news/27584/kingdom-hearts-sold-how-many, archived at Wayback Machine. ↑

Chris Winkler, “Square Back in the Black,” RPGFan, March 30, 2003, accessed September 1, 2020, https://www.rpgfan.com/news/2003/1269.html, archived at Wayback Machine. ↑

The Gummi Ship system was not well received by players in the first game, which prompted Nomura to overhaul it in Kingdom Hearts II. The new system was modeled less like a transportation system but more like a Disney theme park ride with its own story to give players a sense of accomplishment when traveling through the Gummi Ship instead of merely moving from one point to another. Tetsuya Nomura, “Interview,” 1UP.com, May 1, 2005, https://www.kh13.com/interviews/1up-com-may-2005-x-tetsuya-nomura/. ↑

Erika Doss, “Making Imagination Safe in the 1950s: Disneyland’s Fantasy Art and Architecture,” in Designing Disney’s Theme Parks: The Architecture of Reassurance, ed. Karal Ann Marling (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1997), 182. ↑

Doss, 182. ↑

In regard to the possible relationship between mukokuseki anime and modern Japanese cultural identity, famed animation director Mamoru Oshii suggests that the deliberate de-Japanizing of the characters in Japanese animation reflects attempts by the Japanese to “evade the fact that they are Japanese” and even quoted fellow director Hayao Miyazaki’s provocative statement that “the Japanese hate their own faces.” Mamoru Oshii, Ueno Toshiya, and Ito Kazunori, “Eiga to wa jitsu wa animeshon datta,” Eureka 28, no. 9 (1996): 78–80. ↑

Denis Wilson, “A Look under the Hoodie,” New York Times, December 23, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/23/opinion/23wilson.html. ↑

Kohler, Power-Up, 79. ↑

Doss, “Making Imagination Safe,” 181. ↑

Göran Isacson, comment on Kazuma Hashimoto, “Tetsuya Nomura Believes Kingdom Hearts: Dark Road Was Destined to Happen,” Siliconera, June 22, 2020, https://www.siliconera.com/tetsuya-nomura-kingdom-hearts-dark-road/. ↑

Shubhankar Parijat, “Kingdom Hearts 3 Director Told Disney He Wouldn’t Make the Game Unless He Could Use Pixar and Toy Story,” Gaming Bolt, January 6, 2019, https://gamingbolt.com/kingdom-hearts-3-director-told-disney-he-wouldnt-make-the-game-unless-he-could-use-pixar-and-toy-story. ↑

Scott Baird, “Here’s Why Kingdom Hearts 3 Excluded Final Fantasy Characters,” Screen Rant, March 25, 2019, https://screenrant.com/kingdom-hearts-3-final-fantasy-characters/. ↑

See Paolo Ruffino and Jamie Woodcock, “Game Workers and the Empire: Unionisation in the UK Video Game Industry,” Games and Culture 16, no. 3 (2021): 317–328; and Suzanne de Castell and Karen Skardzius, “Speaking in Public: What Women Say about Working in the Video Game Industry,” Television & New Media 20, no. 8 (2019): 836–847. ↑