On the Importance of Community and Belonging

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

When looking over my students’ reflections for a course I recently taught called “Media Experiences and Digital Culture,” I was struck by how often they were pairing positive feedback about our class with a general frustration toward their other learning experiences in college:

- “The structure/flexibility of this course has honestly been a godsend during this busy quarter... I wish more professors had this style.”

- “This course was the best–structured learning experience I have had... I learned a ton, but none of it felt arduous. The culture of the class made us motivated to do work to be accountable to everyone else and ourselves for our learning, not a professor overlord.”

- “One thing I’ve unlearned is that rigid assessments, grades, and course structure promote engagement in the course. I much prefer the structure of this course... [where] you have more agency over your learning.”

- “This course has changed my perspective on how other courses are often unnecessarily burdensome on students in ways that don’t contribute to learning.”

- “For the first time in a while...I felt that I was learning just for the sake of learning and that has always been something I’ve struggled with... I can only hope that academia at large will eventually follow suit.”

My takeaway from this is that our students are seeking a different kind of learning experience than they are used to getting—that they are yearning, even desperate for more learning spaces that are based in trust, choice, connection, and belonging. They want to feel that they are part of a community, that they are being seen, trusted, respected, valued, cared for, included, and that they matter not only as students but more holistically as human beings. We know from research that fostering this sense of belonging—the idea that I matter to this community and it matters to me—is more than just a moral practice; it is also promotes student engagement and leads to deep, transformative learning.[1]

In what follows, I draw from my course “Media Experiences & Digital Culture” to reflect on a few ways I tried to cultivate community and student belonging. The course was an undergraduate seminar that explored the convergence of material culture and digital culture, focusing on the relationship between media industries, fans, and transmedia franchises in the contexts of today’s experience economy. It also opened out onto ethical questions about digital cultural production, algorithms and data surveillance, and the commodification of nature and culture as it relates to media tourism. Our learning team, comprising myself and fourteen students, made use of both physical and digital learning spaces throughout the term.

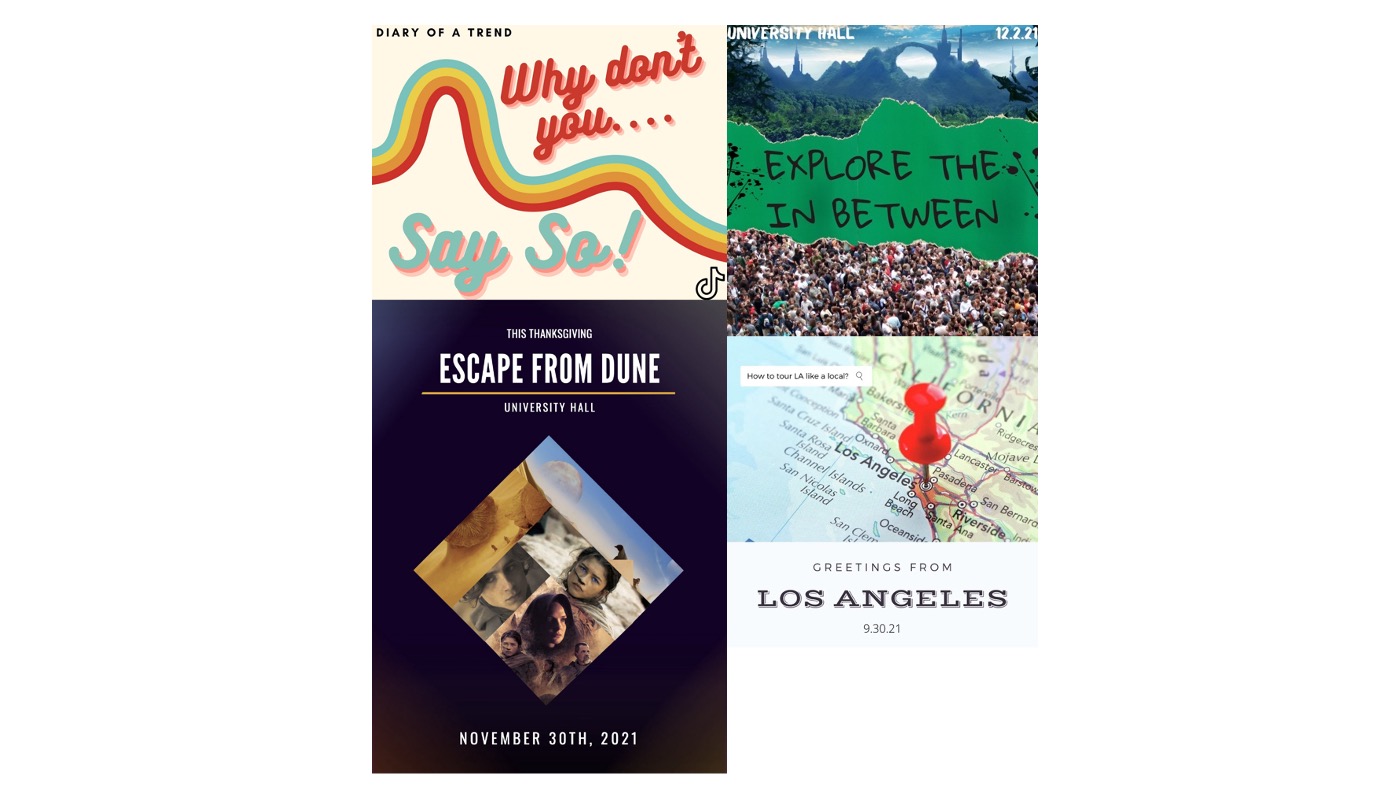

The course was ungraded in the sense that it eschewed traditional grading in favor of ongoing student reflection that culminated in a final self-evaluation and community-based assessment, where each of us acted as readers, participants, audience members, and peer reviewers for each other’s work.[2] Aside from short voice memo reading reflections that were submitted to me via Slack each week, all of our course assignments—four open-ended analyses, a final project, and a final portfolio—were presented to, experienced with, and given feedback by our learning community.[3] By inviting students to design, promote, and stage their own final projects (Figure 1), I sought to dissolve the student-teacher hierarchy by shifting coursework away from the traditionally vertical, private exchange between instructor and student toward a more horizontal, public act of contributing to our shared media diet and community conversations.

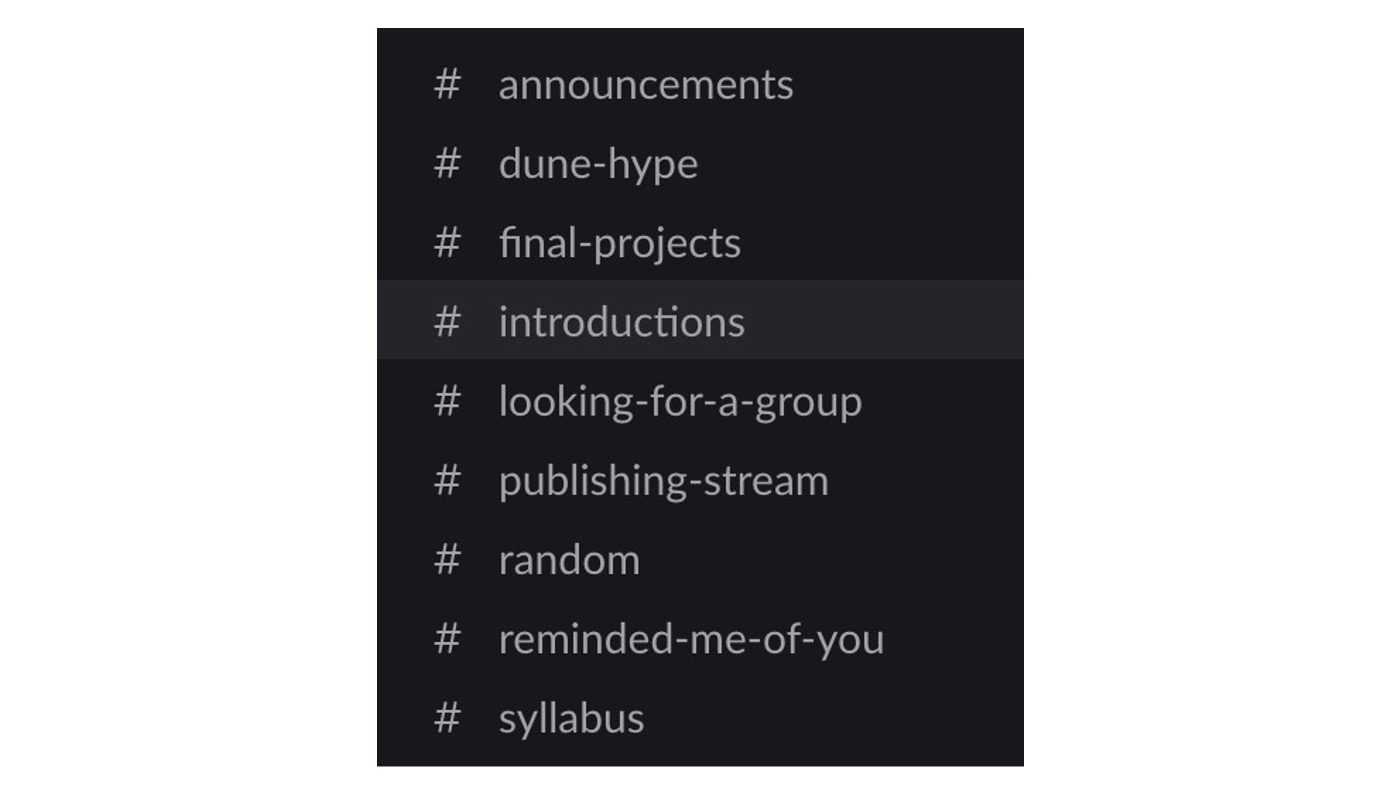

I also worked to extend our sense of community beyond the walls of the classroom, using digital tools like Padlet, Medium, Canvas, and Typeform. Our Slack workspace (Figure 2) included channels like #reminded-me-of-you, which invited students to share and build conversation around things they came across “out there” in the world that reminded them of class. Channels like #dune-hype became a space for us to share self-created memes, promotional paratexts, and collectively anticipate—and in a sense, experience fandom—leading up to our field trip to the movie’s premiere. Students recorded #introduction videos at the beginning of the term and submitted links to their work on the class #publishing-stream throughout the quarter. #Looking-for-a-group served as a community bulletin board, where students shared ideas for assignments and linked up on projects.

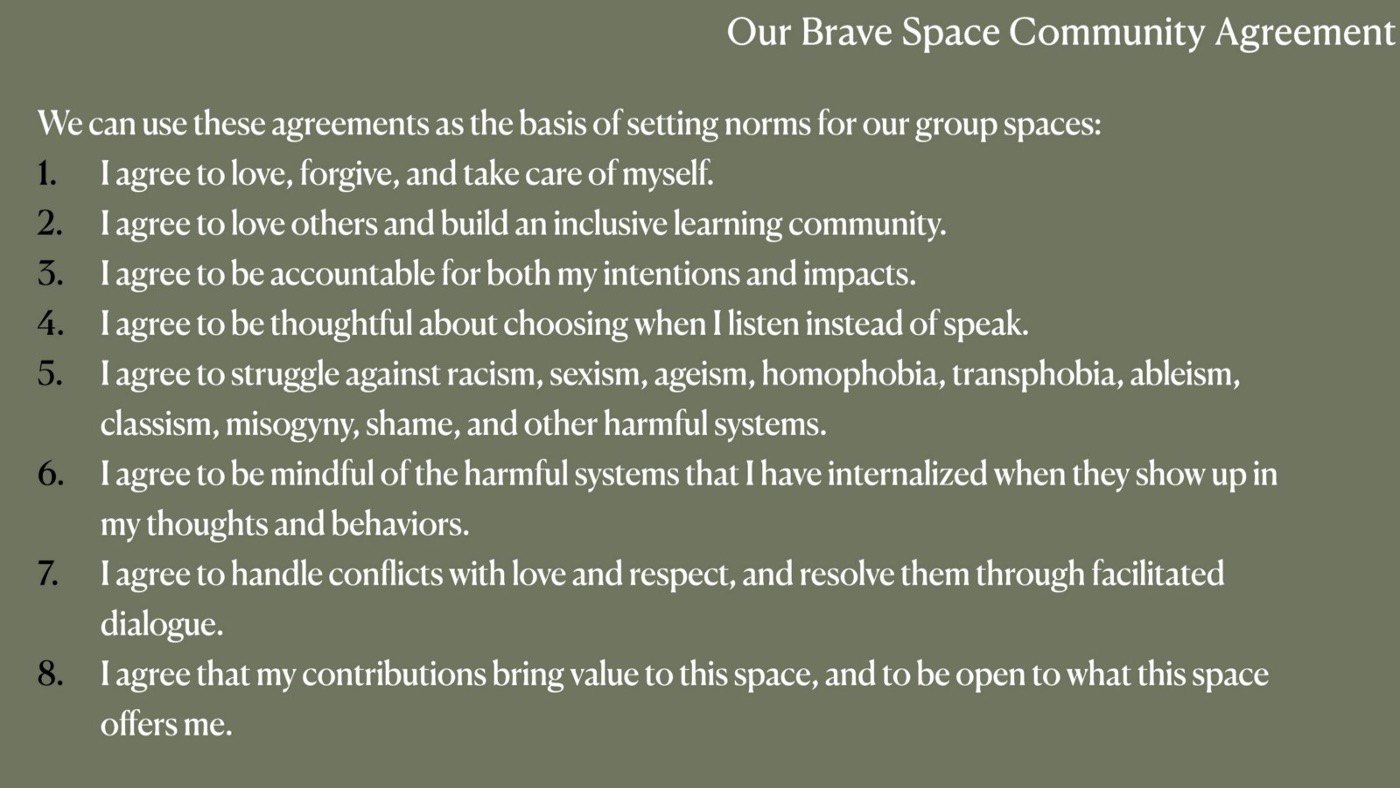

In order to establish a welcoming environment with my students, I leaned heavily on the wisdom of organizations like the Anti-Oppression Resource & Training Alliance and Brave Space Alliance, a Black-led, trans-led LGBTQ+ Center on the South Side of Chicago. These organizations offer brilliant methods for inclusive facilitation and norm setting. They challenge us to start with a simple, terrifying practice: trusting our students, and viewing them as the experts of their own learning experience. On the first day of class, I dedicated a significant amount of time to forming Brave Space Agreements (BSAs) with students. I began by asking them why we might call it a “brave space” as opposed to a “safe space.” This question invited students to critically examine the politics of safety and to be specific about what it looks and feels like to take risks in a supportive environment, to stay silent or speak up, to be vulnerable, to offer support, and so forth.[4] I then displayed a set of agreements on the projector (Figure 3), and split students into pairs. Giving them about 15 minutes, I asked folks to discuss the list and add, edit, or amplify particular statements using Padlet. Through these conversations, students amplified agreements about taking care of themselves and recognizing that they have unique, valuable contributions to make to our shared learning space. They also added words like “patient” and “trusting” to describe the learning community they sought to create. Collectively, we landed on our final version, which I then added to our syllabus. Through this activity, we fostered a sense of belonging by articulating our shared goal to create a supportive, courageous learning space, by acknowledging that what is presented in this space is genuinely open to student input and change, and by explicitly centering students’ wholeness and wellbeing. One student wrote in a reflection:

- “The attention to detail in the first class surrounding our brave space agreement and encouraging us to learn about each other through introductions was a refreshing change of pace from my typical classes. These items specifically made me feel seen and heard immediately in a space where I initially felt intimidated by the RTVF major/minors.”

Importantly, we return to these BSAs throughout the course during self-reflective course check- ins. This affords students a chance to suggest amendments and develop metacognition by reflecting on their own positionally within the community and culture we’ve established:

- “I’ve always had a lot of trouble participating in class but I have felt in the past week or two I have been able to share my thoughts without feeling super nervous. I will definitely keep improving over the quarter but I think the environment does make me feel like my work is valued.”

- “I think we’ve all done a good job respecting each other’s rules and wishes. I’ve definitely been trying to talk less and open up the floor to others. I have a problem not shutting up sometimes.”

- “...we can probably all do better as students to be more present during class—maybe listing this more explicitly in the BSA would keep ‘being present’ ... in the forefront of everyone’s minds.”

As we try on and adapt various pedagogical approaches to meet the needs of ourselves and our students, I want to echo bell hooks in saying that “learning to live in community should be a core practice” of our equity and belonging work.[5] My attempts in this particular class looked like a combination of vulnerability and horizontality, multiplicity and structured flexibility, experiential learning, community-based assessment, and metacognition through self- evaluation. One way I have tried to connect all of these concepts is to model what it looks like to be an open, excited, vulnerable learner. This has helped me transcend my fear-based mindset about having to be the “expert,” and it also suggests to students that their voices and ideas matter—that I am eager to learn from them, and from what emerges in our shared space.

Catherine Shea Sanger, “Inclusive Pedagogy and Universal Design Approaches for Diverse Learning Environments” in Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education, ed. Catherine Shea Sanger and Nancy W. Gleason (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 33; also see Terrell Strayhorn, College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students (Routledge, 2018), 3. ↑

I adapted this technique from Jesse Stommel’s “Digital Studies 101” course. Also see Asao B. Inoue, “Community-Based Assessment Pedagogy,” Assessing Writing 9 (2005), 208-238. ↑

My idea for weekly voice memo reflections was inspired by Juan Llamas-Rodriguez, “Listening to a Train of Thought: Voice Memos as Alternative to Discussion Board Posts,” Flow 27, no. 5 (2021). I also gave students the option to submit written responses each week if they felt uncomfortable or preferred working through their reactions via writing. No students chose this route, but at least making the option available afforded students another choice along their learning path. ↑

Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens, “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: Anew Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice,” in From the Art of Effective Facilitation (Stylus Publishing, 2013), 142. ↑

bell hooks, Teaching Community (New York: Routledge, 2003), 162. ↑