Witnessing Death: The Circulation of Lu Xun’s Postmortem Image[1]

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

At 5:25, early on the morning of October 19, 1936, the influential writer Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881–1936) passed away in his home in Shanghai.[2] His friends recorded this painful moment in different ways, such as sketches, woodblock prints, a film, and a death mask. Some of the images most widely circulated immediately after Lu Xun’s death, however, were his postmortem photographs, which were published in multiple newspapers and inspired other forms of image production. In this paper, I argue that images of Lu Xun’s death gradually transformed from a bond connecting the living and the dead to a politicized icon through its trans-medial circulation. This transformation exemplifies an increasingly sophisticated and diverse understanding and manipulation of photographic images in 1930s China.

The postmortem photo of Lu Xun is an important part of the history of the interaction between images of death and print media. According to Cai Tao, Lu Xun’s death and funeral served as a site of competition among various media: Photography was timelier and more journalistic, he argues, and thus was superior to other forms such as sketches and woodblock prints.[3] Building on Cai’s argument, I examine Lu Xun’s postmortem photos, and show how their iconic and indexical immediacy to the moment of Lu Xun’s death made them the dominant device of mourning and commemoration. Moreover, because images of death were considered inauspicious taboos in traditional China, the wide circulation of his postmortem image epitomizes a fundamental change in people’s understanding of the function of photography in early-twentieth-century China.

In the context of Lu Xun’s death, I evaluate how postmortem photos functioned in both private and public spheres, why they were circulated, and how assorted publications and trans-medial circulations changed their meanings and functions. To do so, I examine similarities and differences in the use of photos in Lu Xun’s lifetime and after his death, within his private social circle and in the public realm. I pay attention to how photos were exchanged among friends, getting reproduced in newspapers and resonating with other forms of postmortem images such as prints, paintings, and death masks. I also contextualize the photographic circulation in the cosmopolitan reality of Shanghai in 1936, the year of Lu Xun’s death, in terms of the influence from Europe and America, the Soviet Union, and the approaching Sino-Japanese War. The postmortem photos announced the death of Lu Xun as well as the birth of an image whose life began the moment the shutter button was pressed and continued throughout time and place, evolving and engendering new meanings.

1. Photography in Lu Xun’s Lifetime

Before jumping into the moment of Lu Xun’s death and talking about how artistic, political, and cultural figures used and interpreted his image, I want to discuss how Lu Xun understood and circulated his own photos. Based on his discussion of photos and his use of photography in daily life, I argue that he considered photography to be an important tool in self-fashioning and social networking, resonating with the communitive mourning channeled by his own postmortem images.

When talking about Lu Xun and photography, one must mention his famous essay “On Photography and Related Matters” (論照相之類, Lun zhaoxiang zhilei).[4] In it, he seems to be criticizing both people who are afraid of photography and those who are too eager to embrace this technology. He sarcastically comments on the belief of people in “S City” that the “foreign devils” used “pickled eyes” as materials for photography, and notes that some refused to take photos for fear that their “spirit could be stolen by the camera.”[5] He then recalls his childhood memory of seeing photos of Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 (1823–1901) and other Qing officials in a studio, criticizing how the new technology was “used to transmit outdated messages.”[6] Lu Xun also comments on images of cultural figures, Chinese and non-Chinese, including the famous photo of Mei Lanfang 梅蘭芳 (1894–1961) cross-dressing.[7] He points out that while photos of Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910), Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906), and other famous Western writers and artists bear “traces of tragic suffering and bitter struggle, none were as manifestly ‘good’ as the Celestial Maiden [Mei Lanfang].”[8] Although his tone is (and always has been) intentionally ambiguous, avoiding any direct criticism or praise, his relatively positive attitude toward these tragic and bitter photos of Western writers is visible.

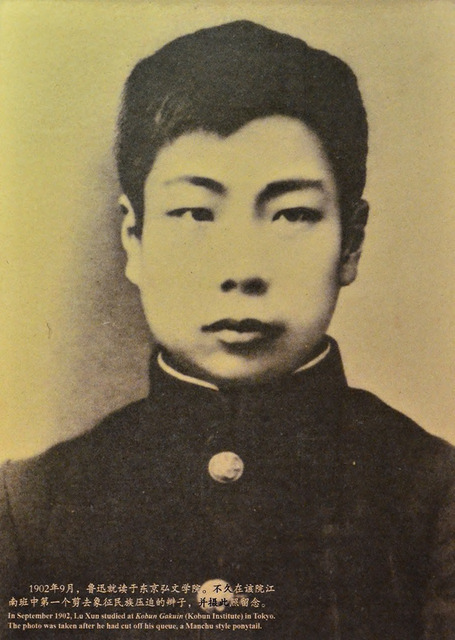

Because Lu Xun considers that a photo shows people the character of its subject matter, it is reasonable to speculate that he would believe that his own photo, when viewed in private or in public, is a powerful tool to construct identity and express ideas.[9] One of Lu Xun’s photos widely discussed by Lu Xun scholars and art historians was taken when he cut off his queue in Tokyo in 1903 (figure 1).[10] Its revolutionary message, as well as the poem inscribed on the back of the photo, has attracted scholarly commentary by Wu Hung, Eileen J. Cheng, and Eva Shan Chou.[11] Here, however, I want to focus on another detail about this photo: Lu Xun sent this image to his friend Xu Shoushang 許壽裳 (1883–1948) as an expression of friendship. Thus, this inscribed picture serves as an example of Lu Xun’s use of photography for both self-fashioning and social networking.[12]

Fig. 1. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun after cutting off his queue, 1903. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.

Fig. 1. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun after cutting off his queue, 1903. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.This approach was not Lu Xun’s invention.[13] Painters in premodern China often exchanged portraits and paintings of their dwellings with inscriptions. In the early twentieth century, many elites used photography as a convenient substitute for paintings and added a modern twist on the traditional practice. As Richard Kent points out, besides echoing the nineteenth-century Western practice of carte de visite, the act of inscribing a photographic portrait as a gesture of friendship is a part of a “long tradition of conjoining images and text” in China.[14] Calligraphic inscription, traditionally regarded as an extension of a literate individual’s presence, and the photographic image bearing the likeness of the sitter invested the portrait “with a certain emotional authority or resonance.”[15] Kang Youwei 康有為 (1858–1927), for example, once inscribed his photo on the frame and gave it as a gift to Qu Hongji 瞿鸿禨 (1850–1918) in 1917 (figure 2).[16] The modernist poet Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1897–1931) inscribed and gave his own photo to Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962).[17]

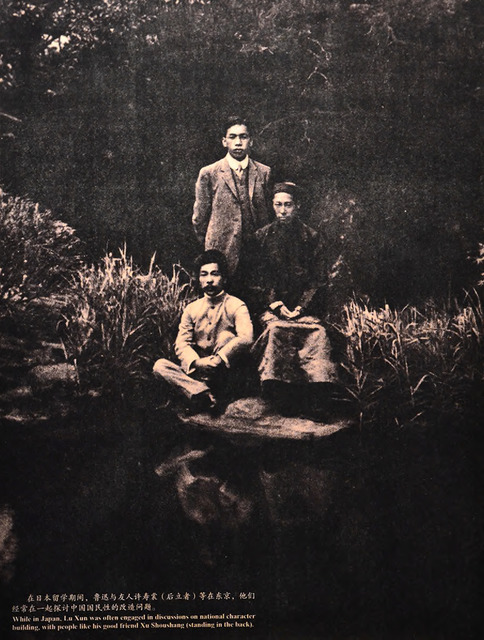

Lu Xun, as one of the cultural elites in modern China, had used photos in a similar fashion. His use of them as a token of friendship can be seen in his photo with Xu Shoushang and Jiang Yizhi 蔣抑卮 (1874–1940), taken in Tokyo in early 1909 (figure 3). In this photo, Lu Xun sits in the front, with Jiang sitting behind him and Xu standing behind both of them. Their artificial pose forms a stable triangle, reminding us of late Qing paintings such as Ren Bonian’s 任伯年 (1840–1896) painting titled Picture of Three Friends 三友圖 (Sanyou tu, 1884). What is more, Lu Xun’s seated pose, holding one leg up with both of his arms, resembles that of Ren Bonian in the Picture of Three Friends.[18] Although there is no evidence that Lu Xun (or the photographer) received direct inspiration from this painting, what matters is that the photo is within the general trend of intermedial interaction between photography and other image production that existed both in China and Japan since the late nineteenth century.[19] On the one hand, visual conventions of paintings influenced photos; on the other hand (as the Okumura Hiroshi oil painting discussed later in this paper shows; see figure 13), photographic portraiture influenced painters’ works as well.

![Fig. 2. Photographer unknown [Powkee Studio], Portrait of Kang Youwei, inscribed as a gift from Kang to Qu Hongji, 1917, courtesy of Shanghai Library. Fig. 2. Photographer unknown [Powkee Studio], Portrait of Kang Youwei, inscribed as a gift from Kang to Qu Hongji, 1917, courtesy of Shanghai Library.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0009.204-00000002-ic.jpg) Fig. 2. Photographer unknown [Powkee Studio], Portrait of Kang Youwei, inscribed as a gift from Kang to Qu Hongji, 1917, courtesy of Shanghai Library.

Fig. 2. Photographer unknown [Powkee Studio], Portrait of Kang Youwei, inscribed as a gift from Kang to Qu Hongji, 1917, courtesy of Shanghai Library. Fig. 3. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun, Xu Shoushang and Jiang Zhiyi in Tokyo, 1909. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.

Fig. 3. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun, Xu Shoushang and Jiang Zhiyi in Tokyo, 1909. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.Besides the intermediality between photography and other forms of image, Lu Xun was consciously manipulating photography, text, and their trans-medial interactions to generate new meanings. In his essay “Mr. Fujino” [藤野先生, Tengye xiansheng], based on his experience as a medical student in Sendai, Lu Xun recounts that his anatomy teacher, Mr. Fujino, gave a photo of himself to Lu Xun. However, Fujino later said that he did not recall giving this young Chinese student a photo.[20] This contradiction between Lu Xun’s essay and Fujino’s memory can be interpreted, as Cheng argues, as a fictionalization of detail for a “more compelling story.”[21] Lu Xun’s specific choice of a photo as a medium of friendship further reveals both a common practice at that time and Lu Xun’s own belief that photography could express and maintain personal connections.

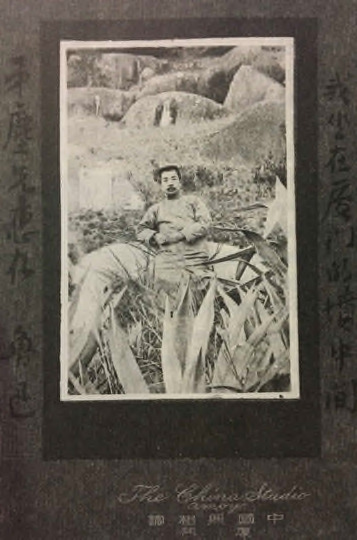

Photography continued to serve an important role in Lu Xun’s self-fashioning and networking after he left Japan. A 1927 photo shows him in the middle of a graveyard in Xiamen (figure 4).[22] On the frame is Lu Xun’s inscription, similar to those on photos of Kang Youwei and Xu Zhimo: “I am sitting amid graves in Xiamen. For Mr. Tingqian. Lu Xun.”[23] This photo was taken on January 2, 1927, after he published his essay collection Graves 墳 (Fen, 1926). Lu Xun’s choice of the graveyard as background echoes what he writes in the preface to the essay collection, “[S]ome people pay homage to the imperial tombs; and others meditate on forsaken graves.”[24] In his countless discussions of the topic, for Lu Xun death marks the truth of the ephemeral nature of life and an attack on hypocrisy.[25] He even created an illustration for his essay collection Graves — a tombstone inscribed with his name “Lu Xun” [魯迅] and “grave” [墳] — with an owl, an inauspicious symbol of death in China, perched on top (figure 5). By representing it in text, illustration, and photography, Lu Xun played with the idea of “death,” which fascinated him throughout his life. [26]

Fig. 4. The China Studio (Amoy), Lu Xun among graves in Xiamen, 1927. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.

Fig. 4. The China Studio (Amoy), Lu Xun among graves in Xiamen, 1927. Shanghai Lu Xun Museum, photo by Yichun Xu.2. Visualizing Death

Compared with a normal portrait, which entails the active engagement of both the subject and the photographer, in postmortem photos the subject (here, Lu Xun) has lost all the agency. However, considering Lu Xun’s active involvement with the art world and his public and private influence, it is not surprising that his death generated a dense visuality of images of him. Ranging from earlier formats such as paintings and prints to the latest technologies of photography, Lu Xun’s postmortem image was passed down in different ways, among which his photograph was the most widely circulated in the immediate few days after his death.

Going back to the early morning of October 19, 1936, a Japanese bookstore owner, Uchiyama Kanzō內山完造 (1885–1959), was one of the first to learn about the death of Lu Xun.[27] He soon sent out messengers by car to Lu Xun’s friends, including the Japanese writer Kaji Wataru鹿地亘 (1903–1982), the Chinese writer Huang Yuan 黃源 (1906–2003), and Xiao Jun 肖軍 (1907–1988).[28] Telephones, radios, telegrams, and the news media soon spread the word from Lu Xun’s personal circle to a broader sphere of interest, and from Shanghai to other cities within and outside China. Cao Juren 曹聚仁 (1900–1972) received the news via a phone call on the morning of the nineteenth.[29] Zheng Zhenduo鄭振鐸 (1898–1958) learned from a newspaper that “Chinese Gorky passed away today at five in the morning.”[30] Mao Dun茅盾 (1896–1981), who might have been in Wuzhen working on his novel at that time, received a telegram from his wife in the afternoon of the nineteenth.[31] The news also reached people in Hong Kong, Japan, Thailand, and the Philippines.[32]

Artists engaged in “a relay of postmortem image production” that contributed to the circulation of the news.[33] Cao Bai 曹白 (1914–2007), Li Qun 力群 (1912–2012), Huang Xinbo 黃新波 (1916–1980), and Chen Yanqiao 陳煙橋 (1911–1970) hurried to Lu Xun’s home, where they drew sketches of him. At two in the afternoon, Mingxing Film Company 明星電影公司 (Mingxing dianying gongsi) learned the news and sent Ouyang Yuqian 歐陽予倩 (1889–1962), Cheng Bugao 程步高 (1898–1966), and Yao Xinnong 姚莘農 (1905–1991) to film the moment.[34]

Meanwhile, the young photographer Sha Fei 沙飛 (1912–1950) received a phone call from the painter Situ Qiao 司徒喬 (1902–1958) about Lu Xun’s death, after which he went to Lu Xun’s home and took several photos.[35] Sha Fei, originally named Situ Chuan 司徒傳, was a member of Situ Qiao’s extended family.[36] In the beginning of the 1930s, he started practicing photography as a hobby and took many tourist photos during his honeymoon.[37] He made his debut as a fine-art photographer in 1935 at the Black and White Photography Society (Heibai yingshe 黑白影社), using his alternative name Situ Huai 司徒懷 (or H. Szeto). He then switched to a documentary approach and became a photojournalist. He had admired Lu Xun, whom he had met at a woodcut exhibition on October 8, 1936. At the exhibition, he took a series of photos of Lu Xun chatting with young woodcut artists (figures 6–8). Only eleven days after the exhibition, Sha Fei took the best-known postmortem photos of Lu Xun.

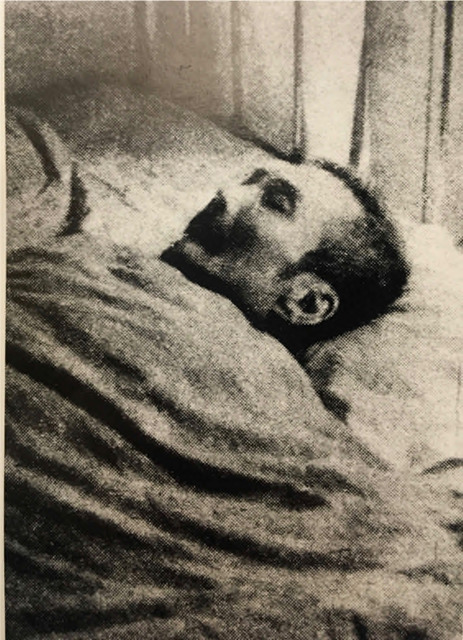

At least two of Sha Fei’s photos taken immediately after Lu Xun’s death were published in the print media. The first was taken from the head of the bed with Lu Xun’s face dominant and central in the frame (figure 9). For the second photo, Sha Fei zoomed out, showing Lu Xun’s face in the lower-left corner and including a part of his desk in the background (figure 10). The first shows details of Lu Xun’s face, such as his wrinkles, raised cheekbones, and closed eyes, whereas the bedroom photo showing the desk offers more information on when and where the image was taken, as well as highlighting Lu Xun’s social standing by showing the desk where he might have spent most of his time writing. There are other postmortem photos of Lu Xun whose creators remain unknown (figures 11 and 12),[38] but all of the photos are striking in their simplicity. Unlike contemporary photographic portraits, there was no “book or scroll” or “very large timepiece,” both features Lu Xun had criticized in his essay on photography.[39] Actually, Lu Xun might have been very happy with his postmortem photos by Sha Fei, as they all bear “traces of tragic suffering and bitter struggle,” like the photos of the great writers he mentioned in his essay.[40]

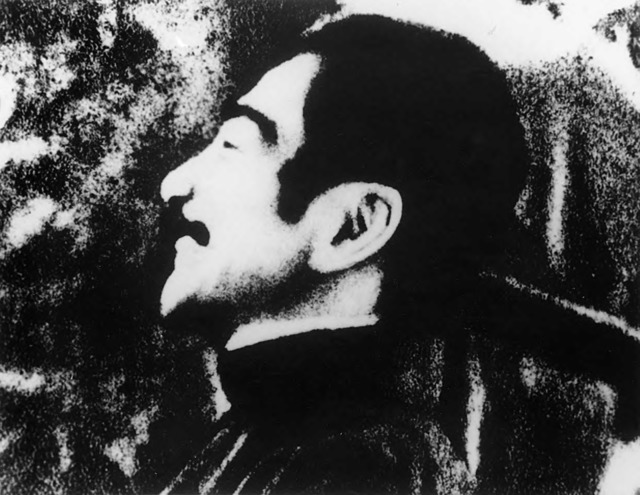

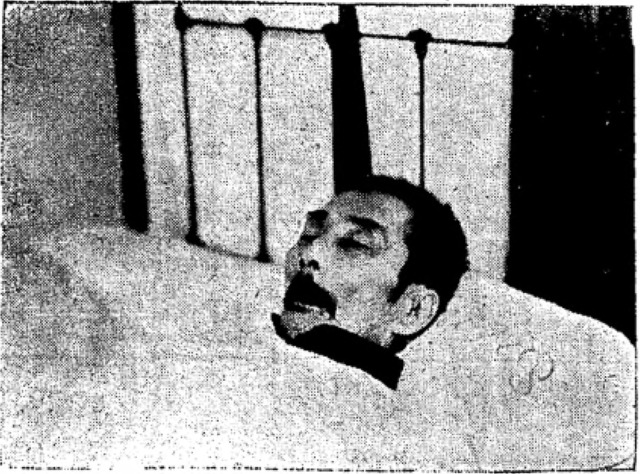

Fig. 11. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun’s postmortem photo, October 19, 1936, Shanhai nichinichi shinbun, October 20, 1936, evening, pg. 2. The III Library of the University of Tokyo.According to Wang Yan, this photo was not taken by Sha Fei.

Fig. 11. Photographer unknown, Lu Xun’s postmortem photo, October 19, 1936, Shanhai nichinichi shinbun, October 20, 1936, evening, pg. 2. The III Library of the University of Tokyo.According to Wang Yan, this photo was not taken by Sha Fei. Fig. 12. Lu Xun’s postmortem photo, October 19, 1936, Sha Fei sheying quanji (Beijing: Changcheng chubanshe, 2005), 38.According to Wang Yan, she later discovered that this photo was not taken by Sha Fei.

Fig. 12. Lu Xun’s postmortem photo, October 19, 1936, Sha Fei sheying quanji (Beijing: Changcheng chubanshe, 2005), 38.According to Wang Yan, she later discovered that this photo was not taken by Sha Fei.The circulation of these postmortem images was also important. Both photos and woodblock prints of Lu Xun’s portrait were reproduced in multiple publications. Considering Lu Xun’s fundamental role in the development of modern printmaking in China and the economical nature of printmaking, it is not surprising that woodblock printers actively engaged in the production of images of mourning for Lu Xun. However, the photos played a more significant role in the first few days after his death given their journalistic immediacy. Among the relevant newspapers and pictorials, at least twenty-one published Lu Xun’s photos from October 19 to the end of 1936, including at least twelve that published Lu Xun’s postmortem photos. The photos did not circulate only in news media; they were also disseminated in private. In a gathering of the Black and White Photography Society, Sha Fei gave many people copies of Lu Xun’s postmortem photos.[41] In this context, the photos became a medium of group memorization as well as a medium of friendship for young artists with similar artistic ideals.

Among these postmortem photos, the mostly widely circulated images were the close-ups. On October 20, one day after Lu Xun’s death, the most influential early newspaper in Shanghai, Shenbao申報 (Shanghai Journal), published an article with three images, one of which was Lu Xun’s close-up postmortem photo.[42] The leftist journal Zhongliu 中流 (Midstream) used Sha Fei’s close-up photo as its cover.[43] Many other journals published close-up photos, such as Xibei Feng 西北風 (Northwestern Wind) and Nüzi Yuekan女子月刊 (The Ladies’ Monthly).[44]

Whereas the bedroom photo shows more contextual information and might work better for documenting a historical moment, the close-ups have a conflicting anachronistic nature — they remind us of the moment of death, but also keep an eternal copy of the likeness of the deceased. Time becomes specific and general, momentary and eternal at the same time: The photo constantly brings the past to the present and brings back the memory of Lu Xun’s death to the viewer.

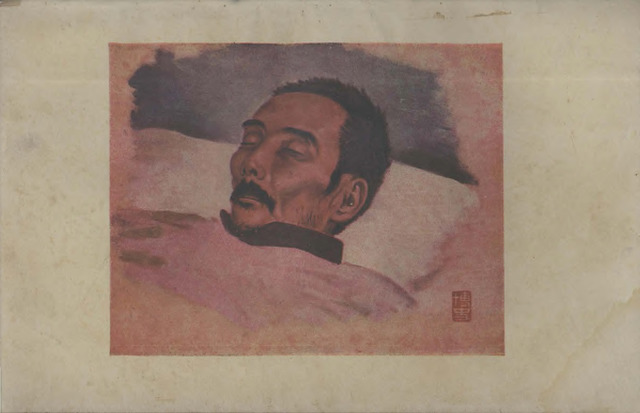

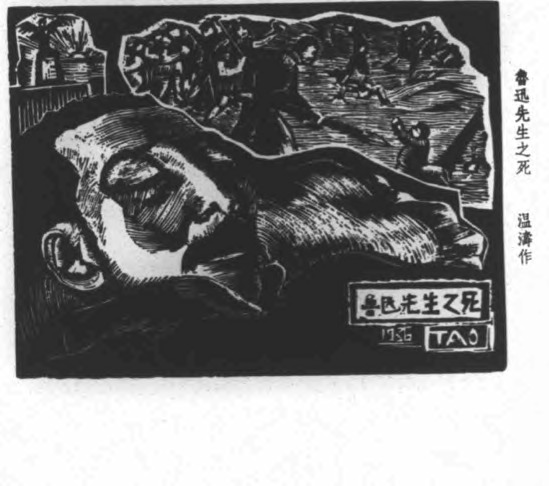

The postmortem photos not only circulated as they were made originally and in news media but were also transformed. For example, Yiwen 譯文 (Translation), a journal Lu Xun was contributing to until the last days of his life, published a three-color print of an oil painting by a Japanese, Western-style painter, Okumura Hiroshi 奥村博史 (1889–1964); see figure 13.[45] This painting was modeled after a photo reproduced in the Japanese-language newspaper Shanhai Nichinichi Shinbun 上海日日新聞 (Shanghai Daily News); see figure 11. Compared with the newspaper photos, the oil painting omits details of the bed and focuses on the bony face of Lu Xun with its traces of suffering. With the photographic image’s indexicality and the spirit captured with the artist’s eye and brush, the oil painting became an ideal for commemoration and collection — Yiwen produced cards with reproductions of it; those who wanted to have a copy for memorialization could purchase a card at a price of three fen分.[46] Five days after Yiwen’s publication of Okumura’s painting, on November 10, Guangming光明 (Light) published a woodblock print by an artist named Wen Tao溫濤 (figure 14).[47] It remains unknown whether Wen modeled the print after a photo, but the visual resemblance of the print to the close-ups is undeniable.

Fig. 13. Okumura Hiroshi, Mr. Lu Xun who has Fallen Asleep Forever, Yiwen 2, no. 3, November 5, 1936, pg. 6.

Fig. 13. Okumura Hiroshi, Mr. Lu Xun who has Fallen Asleep Forever, Yiwen 2, no. 3, November 5, 1936, pg. 6. Fig. 14. Wen Tao, Death of Mr. Lu Xun, woodblock print, Guangming 1, no. 11, November 10, 1936, pg. 1.

Fig. 14. Wen Tao, Death of Mr. Lu Xun, woodblock print, Guangming 1, no. 11, November 10, 1936, pg. 1.How can we explain the popularity of these postmortem photos? One obvious reason for it is that photography provided a fast process of faithful pictorial reproduction, and thus played an important role in bringing the photographer’s personal witness into the public realm. Another reason, I argue, is that the postmortem photo connects viewers both metaphorically and physically to the deceased at the moment of death. Metaphorically, every photographic portrait can be imagined as giving postmortem life to the deceased and anticipating the future death of the living.[48] As Barthes says about the 1865 photo of Lewis Payne taken before he was executed, photography claims simultaneously that “this will be and this has been.”[49]

A number of writers have noticed the close connection between the photo and the death mask, revealing the physical connection between photography and the deceased.[50] The practice of making death masks can be traced back to ancient Roman funerary rites. A death mask functions as an aid to create memorial sculptures that are “commemorative and naturalistic,” rather than idealizing marble busts. This tradition passed on through the centuries and expanded across continents.[51]

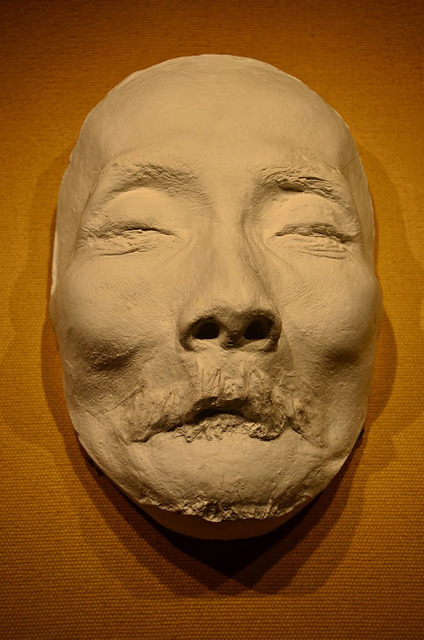

On the day of Lu Xun’s death, a Japanese dentist, Okuda Kyōka奥田杏花 (dates unknown), brought plaster to Lu Xun’s home and made a mold for the death mask. Lu Xun’s son, Zhou Haiying周海嬰 (1929–2011), gives a vivid description of the process:

I remember a Japanese sculptor who came and made a [mold for the] death mask. He first applied a thin layer of Vaseline on a piece of cloth, and then applied wet plaster on the face [of my father]. He gently smoothed the plaster and covered it with the cloth. After the plaster was dry, he took off the mold. When he examined the mold, I saw much of my father’s mustache was stuck to the mold. I was very uncomfortable, feeling that the hair was pulled from my own body.[52]

The resulting death mask is now on display in the Shanghai Lu Xun Museum (figure 15). It has been valued like a relic of Lu Xun, especially with the hairs pulled out from him.

To make a death mask, one needs to apply the plaster onto the face of the deceased; the resulting mold keeps both an indexical (it has a physical connection to the deceased) and iconic (it bears the likeness of the deceased) association with the deceased.[53] From this perspective, we understand the significance of the death mask in the mourning of the dead in that it functions “as an attempt to hold on to the person” the moment when he or she is no longer with the living, [54] in both a physical sense and a visual one.

It is not difficult to see why postmortem photography has a similar connection to death as the death mask does, when we consider they have similar production procedures — the light becomes the medium between the negative and the deceased, as well as the proof of the postmortem photography’s physical indexicality to the deceased. As Kaplan comments, “The molding and impressing of the embalmed face in wax gives way to the molding and manipulation of light cast upon the body of the photographic subject.”[55] What is more, photography is different from the death mask because it is challenging for the latter to be circulated and mass produced. During the age of prosperous print culture, photography became a powerful medium of memorializing the dead as it circulated easily and enabled more people to take part in the process of mourning.

3. Contextualizing Death

If postmortem photos were so meaningful in the memorization of the dead, why were Lu Xun’s photos among the earliest examples despite the fact that photography came into China almost one hundred years earlier? To answer this question, it is important to notice how Lu Xun’s postmortem photos contrast with Chinese people’s earlier ancestor portrait practices, which first originated from ancestor worship and then were remodeled into Confucian filial piety. A traditional ancestor portrait in China can be painted from life or after death. In either case, it depicts the deceased in “full-length, customarily in a rigidly frontal and symmetrical pose seated in a chair, and wearing formal, highly decorated clothing . . . with a somber forward gaze and impassive mouth.”[56] On rare occasions, death was represented directly for reporting and raising public awareness. For example, the illustrated volume A Man of Iron’s Tears for Jiangnan江南鐵淚圖 (Jiangnan tielei tu), published by Yu Zhi余治 (1809–1874), depicts tragic scenes of death in Jiangnan as a result of the Taiping wars, in order to inspire donations to help refugees.[57] As photography became popular in China, pictures of the deceased became prominent features of funerals and even appeared on gravestones. However, they always follow the tradition of showing the deceased as alive by choosing photos taken in the individual’s lifetime.

Approaching the twentieth century, images of death started to appear in public more regularly in China. Three factors contributed to this trend: the influence of Western culture, the advent of the illustrated press, and the Soviet revolutionary imagery practice. In Europe and America, representing the moment of death is long-held tradition that can be traced back to memento mori, a Christian practice of reflecting on mortality.[58] Representing the death of the rich and powerful started in the fifteenth century, as an indication of rising individualism and secularism. In accordance with the tradition of representing death for mourning, as soon as photography was popularized, people in Europe and America started to take photos of the deceased. Advertisements by photographers offering postmortem images can be found in 1846.[59] Western photographers also became the first to record death in China. In 1900 and 1901, for example, journals in Europe and America started publishing photos of the public execution of Chinese criminals.[60]

Although photography reached China soon after the announcement of daguerreotype, in 1839,[61] Chinese people rarely used postmortem photos for mourning. Rather, the early examples of published postmortem photos were mostly for journalism and political propaganda, following the tradition of Yu Zhi’s print.[62] According to Claire Roberts, one of the earliest postmortem photos published in newspapers is of the Nanchang magistrate Jiang Zhaotang 江召棠 (?–1906), who died in a conflict with a French missionary.[63] Despite the missionary’s claim that this was a suicide, the camera takes a perspective that clearly shows the wound on Jiang’s neck as evidence of a murder: “We invite everyone to look at it. Does suicide look like this?”[64] Gu Zheng studied the postmortem photos of Song Jiaoren宋教仁 (1882–1913), which were published in newspapers after Song was assassinated.[65] Both Minlibao 民立報 and The True Record 真相畫報 (Zhenxiang huabao) juxtaposed two postmortem photos of Song Jiaoren, one clothed and one naked. The decision to remove Song’s clothes and focus on his wound shows the photographer’s manipulation of the photographic image of death in order to raise public rage and blame the cruel assassination.

A related contribution to the increasing appearance of death in public is the increasing influence of the illustrated press within China. In the early twentieth century, the half-tone reproduction process, a technology invented in the late nineteenth century for reproducing photos onto newsprint, was transported to China, and now images could be shown in newspapers.[66] As early as 1879, Shenbao published more than ten thousand prints of the former U.S. president Ulysses Grant (1822–1885) during his visit in China.[67]

Lu Xun’s postmortem photos might be among the earliest examples of pictures circulated in China not for the purpose of condemning violence and instead for the mixed purpose of mourning and reporting. This shift may be related to the Soviet practice of memorialization of public figures. The noted Soviet writer Maxim Gorky (1868–1936) died on June 18, 1936, four months before Lu Xun’s death. Just as did revolutionary figures in the Soviet Union, such as Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Gorky received the highest level of commemoration and enjoyed a wide media exposure — people circulated postmortem photos and published memorial articles internationally. His death also caused great grief in China, and his postmortem photo was reproduced in the Chinese media (figure 16).[68] This image has in common with Lu Xun’s close-up framing and a simple background. They both show the deceased in bed, with eyes closed, as if in a deep sleep.

Fig. 16. Photographer unknown, Reproduction of Gorky’s postmortem photo, Yiwen, no. 5, July 16, 1936, pg. 6.

Fig. 16. Photographer unknown, Reproduction of Gorky’s postmortem photo, Yiwen, no. 5, July 16, 1936, pg. 6.There is abundant evidence that this media exposure of Gorky’s postmortem image influenced the mourning of Lu Xun in China. On the day of Lu Xun’s death, people had already started to associate him with Gorky. The connection was at first a spontaneous response from a variety of individuals and publications. The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury 大美晩報 (Ta Mei Wan Pao, Damei wanbao), an influential English-language newspaper in Shanghai managed by American editors and known for its anti-Japanese stance,[69] was among the first to relate Lu Xun’s death with Gorky’s.[70] Following The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury, on October 25, Qingdao shibao 青島時報 (Qingdao Times) published an article detailing the Russian people’s response to Gorky’s death and advocating that Chinese should mourn Lu Xun in a similar fashion.[71] Huabei ribao 華北日報 (North China Daily) also published two articles, on November 1 and 2, titled “Lu Xun and Gorky,” commenting on the similarities of these two writers.[72]

4. Politicizing Death

In addition to the photos taken on the day of Lu Xun’s death, a group of pictures were taken at his funeral. One of these is a close-up of Lu Xun in the coffin taken by Sha Fei (figure 17). Despite the blurred reproduction, the writer Wu Sihong 吳似鴻 (1907–1990), in her memoir, gives a vivid description of the appearance of Lu Xun: “slept tranquilly,” with “glossy” hair, “as if he was much younger.”[73] Only later did she learn that people had put makeup on Lu Xun to cover up his poor complexion, the result of tuberculosis.[74] As I will show in this section, these photos did not have the same indexical immediacy and personal quality as had the first group. However, they demonstrate the process of politicizing the image of Lu Xun.

Fig. 17. Sha Fei, Lu Xun at the Wanguo Funeral Parlor, October 20 or 21, 1936, courtesy of Wang Yan.

Fig. 17. Sha Fei, Lu Xun at the Wanguo Funeral Parlor, October 20 or 21, 1936, courtesy of Wang Yan.Lu Xun’s funeral took place when the Japanese military was a source of threat.[75] The Communist Party was looking for opportunities to forge a united front against Japan with the Nationalist Party. Despite his critical attitude toward revolution,[76] Lu Xun had empathized with the revolutionary cause and was very influential with his left-wing followers.[77] The increasing threat from Japan and tension between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party led many to believe that Lu Xun’s death was a key chance to reconstruct Lu Xun’s legacy and use it for different political purposes.[78]

This tense political context helps explain why the funeral was so grandiose despite Lu Xun’s own wishes that his next of kin “quickly put the body in the coffin and bury it at once” without “any commemorative activities.”[79] It is highly possible that Lu Xun’s funeral was part of the political movement in order to force Chiang Kai-shek to work with the Communist Party.[80] According to the memoir by Hu Ziying’s 胡子嬰 (1907–1982), many believed that Lu Xun’s funeral should be held as a funeral for the people — it should be a public ceremony rather than the private event envisioned by Lu Xun before he passed away.[81]

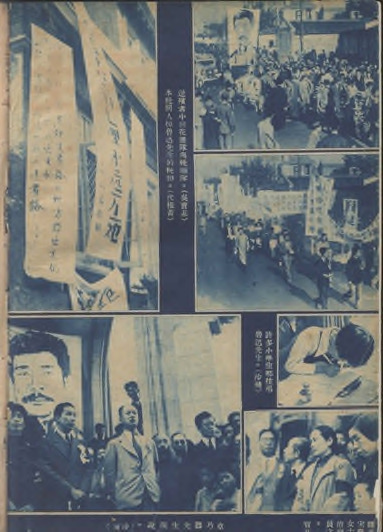

A Lu Xun Funeral Committee 魯迅治喪委員會 (Lu Xun zhisang weiyuanhui) was established on October 19, soon after Lu Xun’s death, with a mix of his relatives and friends as well as political activists.[82] On the afternoon of that day, Lu Xun’s body was sent to the Wanguo Funeral Parlor 萬國殯儀館 (Wanguo binyiguan).[83] The Funeral Committee published obituaries in different news media, announcing the death of Lu Xun and stating that the public could view his body from 10:00 to 17:00 on October 20.[84] The viewing at the funeral parlor was well choreographed. Upon entering, visitors would see several desks on both sides; they would sign in at one desk and then go to the other to have a staff member tie on a black cloth as a symbol of mourning. With the guidance of staff, visitors would walk into the inner chamber from the north door in orderly lines. They would stop in front of the deceased for a second, then walk around in a U-shape, and finally leave through the south door.[85] Forty-four hundred sixty-two people and forty-six groups visited the parlor that day.[86]

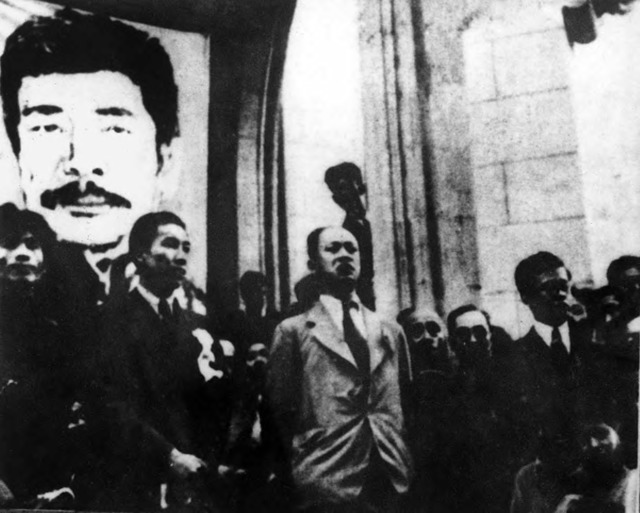

According to the record in JNJ, at 15:00 on October 21, Lu Xun’s body was placed in the coffin. At 13:50 on the 22nd, thirty people carried the coffin and loaded it into a car to be moved to the Wanguo Public Cemetery 萬國公墓 (Wanguo gongmu).[87] The funeral procession arrived at the cemetery at around 16:30 and people held a mourning ceremony there. During the procession, a large ink portrait of Lu Xun, painted by Situ Qiao, was displayed (figure 18).[88] Cai Yuanpei, Shen Junru, Song Qingling, Uchiyama, and many others spoke to the gathering against the threat of being assassinated by the KMT. People used a cloth with calligraphy reading “National Spirit” 民族魂 (Minzuhun), written by Shen Junru, to cover Lu Xun’s coffin, which was then buried.[89]

Fig. 18. Sha Fei, A photo of Lu Xun’s funeral, showing Lu Xun’s ink portrait by Situ Qiao, October 22, 1936, courtesy of Wang Yan.

Fig. 18. Sha Fei, A photo of Lu Xun’s funeral, showing Lu Xun’s ink portrait by Situ Qiao, October 22, 1936, courtesy of Wang Yan.Both Life Weekly生活星期刊 (Shenghuo Xingqikan) and The Young Companion 良友 (Liangyou) published a series of photos recording scenes during the funeral. Whereas Life Weekly was a leftist magazine edited by the famous revolutionary journalist Zou Taofen鄒韜奮 (1895–1944), The Young Companion was less political and known for being “significantly non-partisan.”[90] These different political stances led to different choices of photos and arrangement.

The Young Companion published images of Lu Xun’s funeral on several pages, accompanying reports of Chiang Kai-shek’s fiftieth-birthday celebration (figure 19).[91] On the two pages of reports on Lu Xun’s funeral, the photos — with bilingual captions — were organized into two groups, divided by the title “The Funeral of the Literary Giant, Mr. Lu Xun” and a portrait of him.[92] The upper photos record the process of the funeral: pictures of writers carrying Lu Xun’s coffin, people marching in the street, and important guests, such as Song Qingling, Cai Yuanpei, and Zhang Naiqi 張乃器 (1897–1977). One of the photos shows people carrying banners with slogans. Although most of the slogans are illegible, two words, “Minzu” 民族 (nation) and “Zhonghua” 中華 (China), stand out. The photos in the lower section are of people of all walks of life paying homage. The first pair of photos, one of three males reading the calligraphy on the banner and one of two females wearing Qipao, show that both genders were present; the second pair — one with a little girl and one with an adult male signing their names in the guestbook — represent all ages.

![Fig. 19. China Mourns Over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer, The Young Companion, no. 121, October 1936, pg. 12. Fig. 19. China Mourns Over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer, The Young Companion, no. 121, October 1936, pg. 12.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0009.204-00000019-ic.jpg) Fig. 19. China Mourns Over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer, The Young Companion, no. 121, October 1936, pg. 12.

Fig. 19. China Mourns Over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer, The Young Companion, no. 121, October 1936, pg. 12.Whereas the Young Companion’s emphasis on diversity and such words as “nation” and “China” provides an image of unified people mourning Lu Xun as a nonpartisan “literary giant,” the editors of Life Weekly placed slogans with more radical messages most prominently, intending to turn Lu Xun into a “revolutionary hero”[93] (figure 20). The largest photo on the page, in the upper left, shows a close-up of two banners made by writers of the journal. The right banner, with its first few characters blurred and illegible, has the last four characters “never dies” 永远不死 (yongyuan busi). The left one is a creative borrowing from Lu Xun’s analogy of the road in “My Old Home” 故鄉 (Guxiang): “hope cannot be said to exist, nor can it be said not to exist. It is just like roads across the earth. For actually the earth had no roads to begin with, but when many pass one way, a road is made.”[94] Another photo is of people marching in the street and carrying banners. The one in the front reads “Du Fu embraces the sorrow of the hungry and the suffering; Li He devotes heart and soul [to the people]” 杜少陵愴懷饑溺,李長吉嘔出心肝 (Du Shaoling chuanghuai jini, Li Changji ouchu xingan). It compares Lu Xun to the Tang poets Du Fu 杜甫 (712–770) and Li He 李賀 (790–816), both known for their compassion for the people and criticism of the government.

Fig. 20. Wu Baoji, Shen Zhenhuang, Sha Fei, Photos published in Life Weekly 1, no. 22, November 1, 1936, pg. 1.

Fig. 20. Wu Baoji, Shen Zhenhuang, Sha Fei, Photos published in Life Weekly 1, no. 22, November 1, 1936, pg. 1.Throughout the process of image production and circulation, that of Lu Xun spread from an intimate circle of friends to a broad public, and transformed him from someone the viewer knew to someone unknown.[95] As the circulation grew wider, people with different agendas added “makeup” to the face of Lu Xun and viewers had to increasingly rely on text and other information to understand Lu Xun, thus marking a detachment of the real Lu Xun from his public image. Wu Hung conceptualizes the relationship between a subject and its public image based on four operations: magnifying, substituting, masking, and detachment.[96] If Wu Sihong’s observation of the makeup on Lu Xun resonates with what Wu Hung calls “masking,” idealizing Lu Xun’s face (see again figure 17), the large ink portrait in the funeral procession is both substituting and magnifying him, representing the deceased writer as a living heroic figure (see again figure 18). The media representation of Lu Xun’s funeral with edited information shows a further detachment of his image from himself — he became a nonpartisan literary giant or a revolutionary martyr, despite the fact that he endorsed neither a personal cult nor revolutionary martyrdom (figures 19 and 20).

This detachment continued with the party-sponsored exhibitions on Lu Xun after 1949, followed by the establishment of Lu Xun Memorial Halls in Shanghai, Beijing, Shaoxing, and many other cities.[97] Throughout the Mao era, Lu Xun was canonized as a leftist martyr in the historical narrative dominated by the Communist Party. In the post-Mao era, with increasing influence from consumer culture, Shaoxing even opened a theme park featuring Lu Xun and characters from his novels. Lu Xun’s images were now turned a commodity of nostalgic recollection.[98]

5. Conclusion

Recent scholarship has noted that the history of photography in China is not as simple as the encounter between Western technology and Eastern tradition. The moment of Lu Xun’s death and the circulation of its visual products illuminates the historical complexity of photography in China, as well as the philosophical complexity of photography in general. By zooming in on this historical moment, we observe struggles and compromises emerging from the surface of the circulated photographic images — between personal emotion and political agendas, vernacular practice and international influences, and the private use and public perception of photography. The wide circulation of Lu Xun’s postmortem images also reveals the flexible nature of photography, with its iconic and indexical connection to death, enabling photography to be a powerful medium that channels journalism, the mourning of death, and political propaganda in the early twentieth century.

Yiwen Liu is a PhD candidate studying modern Chinese art history at The Ohio State University. She is currently completing her dissertation on department store exhibition spaces in Republican Shanghai.

This article was inspired by Kirk A. Denton’s seminar on Lu Xun, Gu Zheng’s lecture at OSU, and Namiko Kunimoto’s seminar on photography theory. Many thanks go to my adviser, Julia F. Andrews, for her thoughtful suggestions at various stages in the writing of this article. I would also like to thank Sha Fei’s daughter, Wang Yan, the University of Pennsylvania, III Library of the University of Tokyo, and Yichun Xu for their generous help. Any errors are my own.

Xu Shoushang许寿裳, “Lu Xun xiansheng nianpu” 鲁迅先生年谱 [Chronology of Mr. Lu Xun], in Lu Xun Xiansheng jinian ji (鲁迅先生纪念集 [Mr. Lu Xun: A Memorial] (Shanghai: Wenhua shenghuo chubanshe, 1937 [reprinted in 1979]), 10. I will use JNJ as an abbreviation for Lu Xun Xiansheng jinian ji.

Cai Tao 蔡涛, “Lu Xun zangli zhong de Sha Fei he Situ Qiao — Jianlun zhanqian Zhongguo xiandai yishu de meijie jingzheng xianxiang” 鲁迅葬礼中的沙飞和司徒乔—兼论战前中国现代艺术的媒介竞争现象 [Sha Fei and Situ Qiao in the Funeral of Lu Xun — On the Media Competition in the Modern Art of Prewar China], Wenyi lilun yu piping, no. 5 (2017): 139.

Lu Xun, “On Photography and Related Matters,” in Jottings Under Lamplight, eds. Eileen J. Cheng and Kirk A. Denton, trans. Kirk A. Denton (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2017), 262–69.

Eileen J. Cheng, “Performing the Revolutionary: Lu Xun and the Meiji Discourse on Masculinity,” in Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 27, no. 1 (2015): 1–43.

For more discussion of Lu Xun’s comment on Mei Lanfang’s photo and his distaste for cross-dressing, see Eileen J. Cheng, Literary Remains: Death, Trauma, and Lu Xun's Refusal to Mourn (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press: 2013), 102–107.

Cheng comments that Lu Xun not only actively used photos to show his ideal of masculinity, but that the change of his self-fashioning in photos also reflects his changing views of revolution. See Cheng, “Performing the Revolutionary: Lu Xun and the Meiji Discourse on Masculinity.”

Lu Xun, born Zhou Shuren 周樹人, first used his famous pen name, “Lu Xun,” in 1918.

Wu Hung, Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China (London: Reaktion Books, 2016), 111–15. Eileen J. Cheng, “Performing the Revolutionary: Lu Xun and the Meiji Discourse on Masculinity, in Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 27, no. 1 (2015): 1–43. Eva Shan Chou, “‘A Story about Hair’: A Curious Mirror of Lu Xun’s Pre-Republican Years,” in The Journal of Asian Studies 66, no. 2 (2007): 421–59. Eva Shan Chou, Memory, Violence, Queues: Lu Xun Interprets China (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Association for Asian Studies, 2012).

Cheng has written on this aspect of the photo “as a token of friendship exchanged between male literati to solidify their affective ties.” See Eileen J. Cheng, “Performing the Revolutionary: Lu Xun and the Meiji Discourse on Masculinity,” 1.

For example, late-Qing artists such as Ren Bonian 任伯年 would paint portraits for friends as an intimate practice. See Roberta Wue, Art Worlds Artists, Images, and Audiences in Late Nineteenth-Century Shanghai (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, HKU, 2015), 164.

Richard K. Kent, “Inscribed Photographic Portraits: Commemoration and Self-Fashioning in Republican-Period China,” in Portraiture and Early Studio Photography in China and Japan, eds., Luke Gartlan and Roberta Wue (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 117, 127.

See Yi Gu, “Powkee and the Era of Large Studios,” in Portraiture and Early Studio Photography in China and Japan, 64.

Based on the facial features, the one on the right might be Ren Bonian. Although the inscription on the painting describes Jintang as facing left and Ren Bonian facing right, it is difficult to know which direction the inscription was referring to.

Scholars have recently been aware of the intermedial exchange between photography and other forms of image production in the early history of photography in Japan and China. Besides the aforementioned study of the use of inscription on photography examined by Kent, the artistic value of photography was based largely on the ideals of painting. See Kent, “Inscribed Portraits;” and Kerry Ross, Photography for Everyone: The Cultural Lives of Cameras and Consumers in Early Twentieth-Century Japan (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2015), 129–66. Studies have also shown how photography influenced the production of prints and paintings. According to Sebastian Dobson, the intermedial connection between photography and other media in Japan can be traced back to Japanese printmakers who used photography in their work in the 1870s. According to Claire Roberts, as early as the late nineteenth century, Chinese artists such as Ren Xiong and Lamqua have been influenced by photography as a new way of seeing and created paintings with both the likeness and spirit of the subject. See Sebastian Dobson, “Guiding the Sitter,” in Portraiture and Early Studio Photography in China and Japan, 90; and Claire Roberts, “Chinese Ideas of Likeness: Photography, Painting, and Intermediality,” in Portraiture and Early Studio Photography in China and Japan, 97–116.

Eileen J. Cheng, “‘In Search of New Voices from Alien Lands:’ Lu Xun, Cultural Exchange, and the Myth of Sino-Japanese Friendship,” in Journal of Asian Studies 73, no. 3 (2014): 609.

Huang Qiaosheng黃乔生, Lu Xun xiangzhuan 鲁迅像传 [The Visual Biography of Lu Xun], (Guiyang: Guizhou renmin chubanshe, 2013), 150.

Reproductions without the inscription are also extant in different publications, proving that multiple copies of the same photo exist. See Zhou Haiying周海婴, Shanghai Luxun Culture Foundation, 上海鲁迅文化发展中心, Lu Xun jiating daxiangbu鲁迅家庭大相簿 [The Photo of Lu Xun’s Family] (Beijing: Tongxin chubanshe, 2005), 34.

Lu Xun, “Preface to Graves,” in Jottings Under Lamplight, trans. Theodore Huters (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2017), 29–30.

For example, in his famous poem “Lilun” [立論, Argument], in Wild Grass野草 (Yecao, 1925), he states that at the birth of a newborn baby, the only truth is that the child is going to die, yet that is the most unwelcome comment.

Cheng, Literary Remains, 2. Lu Xun’s early experience as a medical student might also have influenced his attitude about death.

The Shanghai incident on January 28, 1936, destroyed telephone lines in the Hongkou and Zhabei areas. Despite that, Lu Xun’s widow, Xu Guangping 許廣平 (1898–1968), sent out a messenger to the Uchiyama Bookstore and told him the news. Yiqun以羣, “Yi Lu Xun xiansheng” 憶魯迅先生 [In Memory of Mr. Lu Xun], in JNJ, 3/90.

Uchiyama Kanzō, “Yi Lu Xun xiansheng” 憶魯迅先生 [In Memory of Mr. Lu Xun], in JNJ, 2/4. Huang Yuan, “Lu Xun xiansheng” 魯迅先生 [Mr. Lu Xun], in JNJ, 3/106–107.

Cao Juren, “Lu Xun xiansheng” 魯迅先生 [Mr. Lu Xun], in JNJ, 4/57.

Zheng Zhenduo, “Yongzai de wenqing”永在的溫情 [Everlasting Warmth], in JNJ, 1/89.

Maodun, “Xieyu beitongzhong” 寫於悲痛中 [Writing in Pains], in JNJ, 1/99.

For example, Zhujiang ribao and Gangbao, two newspapers in Hong Kong, reported the death of Lu Xun on October 20. Huaqiao ribao, in Thailand, reported the news on October 22. See JNJ, 2/13.

Cai Tao, “Lu Xun zangli zhong de Sha Fei he Situ Qiao,” 135.

Ke Ling科靈, “Wentan juxing de yunluo”文壇巨星的隕落 [The Fall of a Literary Giant], Shenbao (October 20, 1936): 11. I have not been able to locate the film.

Wang Yan 王雁, Wode fuqin Sha Fei 我的父亲沙飞 [My Father H. Szeto] (Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2005), 58.

Eliza Ho and Sha Fei, Art, Documentary, and Propaganda in Wartime China: The Photography of Sha Fei (Columbus: East Asian Studies Center, Ohio State University, 2009), 6.

Sha Fei’s career coincided with the popularization of cameras and the growth of both amateur and professional photographers, as point-and-shoot cameras became readily available and personal cameras became more affordable. According to the biography of Sha Fei, he obtained a fortune of five hundred yuan to purchase a professional camera around 1933 or 1934. See Cai Zie蔡子谔, Sha Fei zhuan: Zhongguo geming xinwen sheying diyiren 沙飞传:中国革命新闻摄影第一人 [Biography of Sha Fei] (Beijing: Zhongguo wenlian chubanshe, 2002), 49. The camera that Sha Fei was using was likely similar to a Leica III, which cost 370 yuan and was one of the latest cameras available in Shanghai in 1933, according to an advertisement on Sheying huabao. See “Sheying shichang” 攝影市場 [Photography Market], Sheying huabao vol. 9, no, 35 (1933): 24.

According to Sha Fei’s daughter, Wang Yan, the close-up and the bedroom photos are the only two that she believes to be Sha Fei’s images. Wang Yan, email message to the author December 4, 2018.

Lu Xun, “On Photography and Related Matters,” 265. The trend of taking photographic portraits with elaborate props and backdrops was a way of self-fashioning and inseparable from commercial photography studios, popular between 1890 and 1920, until its decline with the rise of amateur art photography. These studios offered clients an opportunity to “express their fascination with elite literati cultural tradition” as well as with Western and Japanese culture. See Gu, “Powkee and the Era of Large Studios,” 59–76.

“Woguo wentan juzi Lu Xun zuochen shishi” 我國文壇巨子魯迅昨晨逝世 [The Literary Giant of Our Country, Lu Xun, Passed Away Yesterday Morning], Shenbao (October 20, 1936): 9. The other two photos are of Lu Xun’s study room and of Lu Xun’s wife, Xu Guangping, and their son, Zhou Haiying.

Zhongliu 1, no. 5 (November 15, 1936): cover. Zhongliu was founded on September 5, 1936, with Lu Xun as one of its main contributors. Within the same journal is a sketch by Li Qun, together with the bedroom photo.

Xibeifeng, no. 11 (November 5, 1936): 31. Nüzi yuekan 4, no. 11 (November 11, 1936): 50.

Okumura Hiroshi, “Changmianle de Lu Xun xiansheng” 長眠了的魯迅先生 [Mr. Lu Xun Who Has Fallen Asleep Forever], Yiwen, 2, no.3, (November 5, 1936): 5–6.

Ibid., 5. This painting was later reproduced in black and white ten years after Lu Xun’s death, in Wenyi Chunqiu, 1946. See Wenyi Chunqiu 3, no.4 (1946): 1.

Wen Tao, “Lu Xun xiansheng zhisi” [魯迅先生之死, Death of Mr. Lu Xun], Guangming 1, no. 11 (November 10, 1936): 1.

Carlos Rojas, “Abandoned Cities Seen Anew: Reflections on Spatial Specificity and Temporal Transience,” in Photographies East, ed. Rosalind C. Morris (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2009), 207.

Roland Barthes and Geoff Dyer, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 96. Compared with Lewis Payne’s photo, those of Lu Xun’s death offer only one message — He has died. Thus, Lu Xun’s postmortem photos force us to witness death directly without any sort of buffer, tying photography closer to death.

For example, Andre Bazin writes that photographic preservation was a “practice of embalming the dead.” See Andre Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Film Quarterly 13 (4): 4. And Susan Sontag comments on the photograph’s nature not only as an image but also as a trace, “like a footprint or a death mask.” Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Doubleday, 1977), 154. For more discussion on the connection between photography and death masks, see Louis Kaplan, “Photograph/Death Mask: Jean-Luc Nancy’s Recasting of the Photographic Image,” in Journal of Visual Culture 9, no. 1 (April 2010): 45–62; Marcia Pointon, “Casts, Imprints, and the Deathliness of Things: Artifacts at the Edge,” in The Art Bulletin 96. 2 (2014): 170–95; and Patrick R. Crowley, "Roman Death Masks and the Metaphorics of the Negative," in Grey Room (2016): 64-103.

See Marcia Pointon, “Casts, Imprints, and the Deathliness of Things: Artifacts at the Edge,” 171.

Zhou Haiying 周海婴, “Chonghui Shanghai yi tongnian” 重回上海忆童年 [Returning to Shanghai and Recalling my Childhood], in Lu Xun huiyilu 鲁迅回忆录 [Memories of Lu Xun] (Beijing: Beijing chubanshe, 1999), 1271, translated by author.

For concepts of iconic and indexical, see Charles S. Peirce, “Logic as Semiotic: What Is a Sign?” in The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings, vol. 2, 1893–1913 (Bloomington: Indiana University Pres, 1998), 4–10.

Marcia Pointon, “Casts, Imprints, and the Deathliness of Things: Artifacts at the Edge,” 173.

Jiyun shanren 寄雲山人 (Yu Zhi), Jiangnan tielei tu (Taibei: Guangwen shuju, 1974). For a discussion of this print, see Tobie S Meyer-Fong, What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2013).

Nigel Llewellyn and the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual, c. 1500–c. 1800 (London: Published in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum by Reaktion Books, 1991), 9–10. One of the best-known examples of memento mori in Western art history can be seen in the lower section of Masaccio’s fresco The Holy Trinity (1425).

For example, A. J. Beal’s Daguerreian Portrait Gallery in New York published an advertisement in The East in 1846 claiming that “Beal will go in or out of the city to take the sick or the dead.” The advertisement was reproduced in Floyd Rinhart and Marion Rinhart, The American Daguerreotype (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1981), 300.

James L. Hevia, “The Photography Complex: Exposing Boxer-Era China (1900–1901), Making Civilization,” in Photographies East, 79–120.

The earliest-dated photographs of China and Chinese people are taken by a French photographer, Jules Itier, in 1844. See Claire Roberts, “Chinese Ideas of Likeness: Photography, Painting, and Intermediality,” 101. One of the earliest Chinese photographers was Zou Boqi 鄒伯奇 (1819–1869). See Oliver Moore, “Zou Boqi on Vision and Photography in Nineteenth-Century China,” in The Human Tradition in Modern China, eds. Kenneth J. Hammond and Kristin Stapleton (Lanham, Md., 2008), 33–53.

For mourning, it was unprecedented to show a postmortem photo. For example, after Sun Yensen’s death, there was only a photo of Sun’s lifetime and of the funerary, with no close-up of the deceased. See Pictorial Weekly of the Eastern Times 圖畫時報 (March 22, 1925): 1; and Kuowen Weekly國聞月刊 (March 22, 1935): 5, 10.

Claire Roberts, Photography and China (London: Reaktion Books, 2013), 55.

Gu Zheng, “Between Journalism and Propaganda: The Assassination of Song Jiaoren in Minglibao,” paper presented at ICS lecture, Columbus, Ohio, October 27, 2017.

Rudolf G. Wagner, “Joining the Global Imaginaire: The Shanghai Illustrated Newspaper Dianshizhai huabao,” in Joining the Global Public: Word, Image, and City in Early Chinese Newspapers, 1870–1910, ed. Rudolf G. Wagner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), 120.

At least one journal published Gorky’s postmortem photo: Yiwen 1, no. 5 (July 16, 1936): 6.

Yong Volz and Chin-Chuan Lee, "Semi-colonialism and Journalistic Sphere of Influence,” in Journalism Studies (2011), 12 (5): 562, 569.

Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury (October 19, 1936). Cited by JNJ.

See “Sulian aidao Gaoerji, women dui Lu Xun yeyao zheyang aidao” 蘇聯哀悼高爾基,我們對魯迅也要這樣哀悼 [We should mourn Lu Xun like Russians mourn Gorky], Qingdao shibao (October 25, 1936): 11.

“Lu Xun yu Gaoerji” 魯迅與高爾基 [Lu Xun and Gorky], Huabei ribao (November 1, 1936): 12, and (November 2, 1936): 12. Holm points out that left-wing movements in different countries, among them the United States and Germany, shared the tendency to take certain writers as their “figurehead, model, and hero,” related to the “vulgar Marxism” and the Soviet work style developed in the 1920s and 1930s. He argues that the Soviet cult of Gorky and the cult of Lu Xun in China had the same essence — taking a writer as “a living example of the progress from independent progressive and public-minded citizen to committed Communist and revolutionary.” See David Holm, “Lu Xun in the Period 1936–1949: The Making of a Chinese Gorki,” in Lu Xun and His Legacy, ed. Leo Ou-fan Lee (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 157.

Wu Sihong, “Guanyu Lu Xun xiansheng de pianduan huiyi” 关于鲁迅先生的片段回忆 [Pieces of Memories about Mr. Lu Xun], in Lu Xun huiyilu, 3/1408.

David Holm, “Lu Xun in the Period 1936–1949: The Making of a Chinese Gorki,” 153. It is almost needless to mention the outbreak of full-scale fighting in Shanghai in August of the year following Lu Xun’s death.

See Wang Binbin’s analysis of some of Lu Xun’s essays and personal letters written in the 1930s, Wang Bingbing 王彬彬, “Zuowei yichang zhengzhi yundong de Lu Xun sangshi” 作为一场政治运动的鲁迅丧事 [Lu Xun’s Funeral as a Political Movement], Lu Xun neiwai 鲁迅内外 [About Lu Xun] (Nanjing: Nanjing daxue chubanshe, 2013), 183–85.

Lee discusses Lu Xun’s changing attitude toward the revolution and revolutionary literature after 1927. See Leo Ou-fan Lee, “Literature on the Eve of Revolution: Reflections on Lu Xun’s Leftist Years, 1927–1936,” in Modern China 2, no. 3 (1976): 277–326.

Lu Xun, “Death,” in Jottings Under Lamplight, trans. Eileen J. Cheng, 66.

Wang Bingbing, “Zuowei yichang zhengzhi yundong de Lu Xun sangshi,” 179–93.

Hu Ziying, “Huiyi yierjiu dao qiqi Shanghai kangrijiuwang yundong de fazhan” 回忆‘一二·九’到 ‘七·七’上海抗日救亡运动的发展 [Recalling the Development of the Anti-Japanese Movement in Shanghai from the December 9th Movement to the Marco Polo Bridge Incident], in Yierjiu yihou Shanghai jiuguohui shiliao xuanji 一二·九以后上海救国会史料选辑 [Selected Historical Sources of National Salvation Association since the December 9th Movement], ed. Shanghai shiwei dangshi ziliao zhengji weiyuanhui (Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexueyuan chubanshe, 1987), 394.

The funeral committee as announced publicly consisted of Cai Yuanpei蔡元培(1868–1940), Uchiyama Kanzō, Song Qingling宋慶齡(1893–1981), Agnes Smedley, Shen Junru沈鈞儒(1875–1963), Xiao San蕭三 (1896–1983), Cao Jinghua曹靖華 (1897–1987), Xu Shoushang, Mao Dun, Hu Yuzhi 胡愈之(1896–1986), Hu Feng胡風 (1902–1985), Zhou Zuoren周作人(1885–1967), and Zhou Jianren周建人(1888–1984). See the list in the preliminaries of JNJ. According to Feng Xuefeng’s talk at the Lu Xun Museum in 1972, he arrived at Lu Xun’s home thirty minutes after Lu Xun’s death. Song Qingling arrived after receiving Feng’s phone call. She contacted a lawyer named Shen Junru and asked him to buy a tomb for Lu Xun. Feng then discussed the arrangements with Lu Xun’s widow, Xu Guangping, and made a list of people on the Lu Xun Funeral Committee (Lu Xun Zhisang weiyuanhui). Mao was originally included in the list but only Shanhai Nichinichi Shinbum was able to publish the list with Mao’s name in it. See Feng Xuefeng, “Zai Beijing Lu Xun bowuguan de tanhua” 在北京魯迅博物館的談話 [Lecture at the Beijing Lu Xun Museum] (1972), in Lu Xun huiyilu, 2/992–93.

It was the first commercial funeral parlor in Shanghai built by an American businessman, in 1924. See Natacha Aveline-Dubach, Invisible Population — The Place of the Dead in East Asian Megacities (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2012), 74–97,

Wanguo gongmu, built in 1909, was the first Chinese commercial cemetery in Shanghai. Natacha Aveline-Dubach, Invisible Population, 75. On the twentieth anniversary of his death, Lu Xun’s body was ceremoniously moved to Hongkou Park. See Kirk A. Denton, Exhibiting the Past: Historical Memory and the Politics of Museums in Postsocialist China (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2014), 181.

Feng Yimei冯伊嵋,Weiwancheng de hua未完成的画 [An Unfinished Painting] (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1978), 72.

Wu Sihong, “Guanyu Lu Xun xiansheng de pianduan huiyi,” 3/1414.

Paul G. Pickowicz, Kuiyi Shen, and Yingjin Zhang, “Introduction, Liangyou, Popular Print Media, and Visual Culture in Republican Shanghai,” in Liangyou, Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926–1945, eds. Paul Pickowicz, Kuiyi Shen, and Yingjin Zhang (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 1.

See “The Fiftieth Birthday of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek (Special),” in The Young Companion, no. 121 (October 1936): 2–6. “China Mourns over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer,” The Young Companion, no. 121 (October 1936): 12.

The English title is “China Mourns over the Death of Lu-Sun [sic], the Writer.” The Chinese title literally translates as “The Funeral of the Literary Giant, Mr. Lu Xun 一代文豪魯迅先生之喪 [Yidai wenhao Lu Xun xiansheng zhi sang].”

See the photos published in Life Weekly, 1, no. 22 (November 1, 1936): 1.

Lu Xun, Lu Xun: Selected Works, trans. Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1985), 1/101.

Kent points out that without text, a portrait’s subject has a kind of “ambiguous, unstable nature” throughout time. See Kent, “Inscribed Photographic Portraits,” 117–118, 123.

Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), 81.