Landscape Photography, Infrastructure, and Armed Conflict in a Chinese Travel Anthology from 1935: The Case of Dongnan lansheng

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

During the 1930s, a great number of travel-related texts and images were published in China; they were printed in specialized journals, pictorials, newspapers, anthologies of travel writing, and photobooks. The most sumptuous of these publications was a book titled Dongnan lansheng in Chinese (In Search of the Southeast in English). Edited by a Southeastern Transportation Tour Propaganda Committee and sponsored by the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province, it was part of a public-relations campaign that promoted the completion of highways and a railroad in the southeastern provinces. The achievements of modern engineering are, however, not extensively covered in the book; instead, it is an anthology of travelogues and poetry, richly illustrated with a few paintings and numerous photographs. The texts and images were contributed by renowned authors, painters, and photographers.

This article examines how the photographs in Dongnan lansheng negotiate the tasks the book aims to fulfill — to promote travel on modern roads, to map the scenic sites of formerly remote regions, and to convey both the movement of travel and the conventions of Chinese landscape imagery in the medium of photography. I will analyze how the editors arranged the photographs in sequences that suggest the movement of travel through the landscape, assigning various and discontinuous speeds and different temporalities to different places. They thus shaped their readership — presumably educated, wealthy, and male urbanites — into a collective subject whose experience of movement through the landscape forms the main narrative of the book. Moments of violence and anxiety are erased from this narrative, but resurface in one of the travelogues and a photograph.

In February 1934, the Shanghai newspaper Shenbao reported that Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) had given the order to prepare a “Southeastern Infrastructure Tour.” The objective was to speed up the construction of new and the extension of existing highways that linked the five provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Anhui, and Jiangxi, in order to “further cultural progress, the development of transportation, the flourishing of trade, the convenience for the military, the defense against bandits, and the enhancement of public security.”[1] Road construction had a high priority on the political agenda of the Nanjing government, and progressed at a rapid pace.[2] The Southeastern Infrastructure Tour was supposed to commemorate the completion of construction work by the end of June of that same year, and to include exhibitions of local produce and customs, educational material on road safety, and visits to places famous for their scenic beauty, such as Yandangshan, in Zhejiang Province, and Huqiu (Tiger Hill), in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province.[3] Apparently construction work did not progress with the expected speed; the tour was postponed until October.[4] But because natural disasters struck the southeastern provinces, the preparations for the tour were suspended in September 1934 in order to concentrate efforts on relief aid.[5]

Although the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour was never realized, more than one hundred writers, editors, photographers, and painters had already traveled the tour routes at government expense before it was canceled.[6] Shenbao reported repeatedly on the travel activities undertaken in preparation of the tour.[7] In June, for example, readers were informed that the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province had invited a group of photographers from Shanghai to visit Huangshan, a mountain in Anhui Province famous for its beauty, to take pictures to be included in a travel guide to the five southeastern provinces.[8] This publication was mentioned again one month later, in an article announcing the opening of an exhibition with works by young authors and artists that had been solicited in preparation for the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour.[9] Despite the suspension of the actual tour, work on the book proceeded, and it was published in March 1935 under the title Dongnan lansheng 東南攬勝 (“Searching Out Scenic Sites in the Southeast”), and with the English title In Search of the Southeast.

The Chinese and English prefaces to Dongnan lansheng suggest that Zeng Yangfu (曾養甫, 1898–1969), the head of the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province, was the driving force behind the project.[10] During his tenure as head of the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province, from 1931 to 1935, he was responsible for two major infrastructure projects of the Nanjing Decade (1928–37): the construction of the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Railway (Zhe-Gan tielu), completed in 1937, and of the Qiantang River Bridge, between 1934 and 1937.[11] These two projects played a key role in considerations of military defense, especially in light of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, in 1931, and of armed conflicts with Communist forces, as Zeng Yangfu stressed in several speeches and articles on construction politics.[12] A second objective was economic development. In Zeng’s preface to Dongnan lansheng, he claims that the book’s main aims were to praise the newly constructed roads and railways and to inspire tourism.[13]

The imprint names a Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Propaganda Group (Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui xuanchuan zu) as the editorial entity of Dongnan lansheng. The high political profile of the publication is reflected in the names of the members of the Board of Editors listed in the imprint, which read like a Who’s Who of the political, intellectual, and artistic circles of the Shanghai-Hangzhou-Nanjing region. The person listed first is Ye Gongchuo 葉恭綽 (1881–1968), a member of the National Economic Council, former minister of transportation, and renowned calligrapher, who was involved in a wide range of official and unofficial cultural activities;[14] the second is Xu Shiying 許世英 (1873–1964), head of the Relief Commission and a former minister, who in the context of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour initiated the development of Huangshan as a major tourist destination.[15] Among the other members of the board of editors were academics, writers, and painters, among them editors of the magazine Shidai (The Modern Miscellany).[16] The collaboration of the political sphere with the burgeoning tourism sector in this book project is also reflected in the choice of the two editors in chief and their areas of expertise: Jiang Jiamei 江家瑂 served as secretary at the Zhejiang Construction Bureau, and Zhao Junhao 趙君豪 (1900–?) was the editor in chief of China’s major travel magazine, Lüxing Zazhi (The China Traveler).[17]

Travel and tourism were thriving topics in Chinese popular media of the Republican period. Lüxing Zazhi, published by the China Travel Service, was devoted almost entirely to travel reportage and literary travelogues; it also featured one of the earliest reports on the Southeastern Transportation Tour.[18] The country’s most widely read pictorial, Liangyou (The Young Companion), regularly featured spreads about the famous scenic sites of China, as well as on the construction sites of railways, highways, and the Qiantang River Bridge.[19] The editors of Liangyou also published lavishly produced bilingual Chinese-English photographic atlases of China. The first was Zhongguo daguan, or The Living China: A Pictorial Record 1930, which introduced the readership to the country in chapters on various themes, such as arts, politics, and military affairs, as well as scenic sites.[20] The second publication, Zhonghua jingxiang: Quanguo sheying zongji, or China as She Is: A Comprehensive Album,[21] to be briefly discussed later in this essay, was devoted almost exclusively to scenic sites. Texts and photographs previously published in Lüxing zazhi, Liangyou, and several other magazines and in travel-related anthologies and photobooks were included in Dongnan lansheng, as were works by authors and artists invited on the Southeastern Transportation Tour and submissions for the related exhibition held in Shanghai in the summer of 1934. In fact, Dongnan lansheng can be described as the high-end product of a veritable publication campaign.

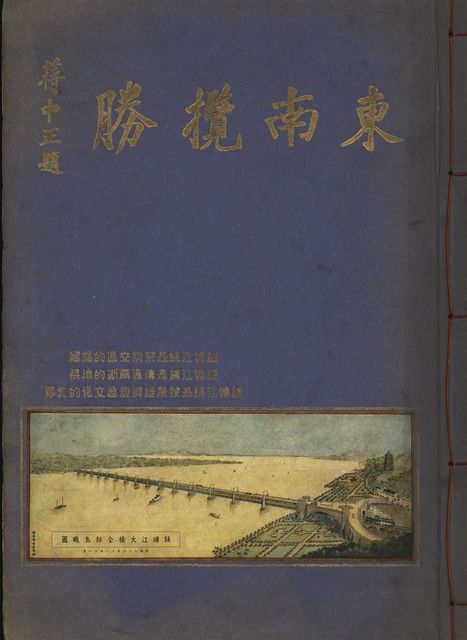

Fig. 1. Cover of Dongnan lansheng (1935), with title calligraphy in the hand of Jiang Jieshi and a design drawing of the Qiantang River Bridge (under construction 1934–37). Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 1. Cover of Dongnan lansheng (1935), with title calligraphy in the hand of Jiang Jieshi and a design drawing of the Qiantang River Bridge (under construction 1934–37). Courtesy Shanghai Library.The political prestige of the infrastructure projects promoted by Dongnan lansheng manifests itself most clearly and prominently on the cover (figure 1): The title was brushed by Jiang Jieshi and printed in gold on the dark blue linen cover; the lower part shows a design drawing of the Qiantang River Bridge, still under construction at the time. This cover image of a monumental engineering project is, however, not representative of the book, in which direct references to infrastructural modernization are remarkably scarce.

In this regard, Dongnan lansheng and related publications from Republican China differ markedly from other, comparable campaigns to promote modern means of transportation, such as the sponsoring of photographers and early filmmakers by railway companies in the United States during the nineteenth century,[22] the publications about the Black and Yellow Cruises by car, which were organized by Citroën in the late 1920s and early 1930s and led across Central Africa and Central Asia, respectively,[23] and, to a lesser extent, in Japanese photobooks on Manchuria.[24] Whereas these publications showcase the engines of modernity very prominently, photographs of trains, cars, roads, and bridges are conspicuously underrepresented in Dongnan lansheng. Instead, the overwhelming majority of the photographs show landscapes untouched by modern infrastructure. Likewise, only a small amount of the texts describe highways, railroads, or bridges in a straightforward way.

Instead, the means of transportation form the structural basis for what at first sight seems to be an engagement with much older cultural practices: Dongnan lansheng is primarily an anthology of travelogues and poetry. These are complemented by photographic and painted images, scholarly introductions on the geography of the province, medicinal herbs originating there, and the history of Huangshan.

A book project that is linked to the highest echelons of the Nationalist government, to the highly symbolic enterprise of national reconstruction originating with Sun Zhongshan,[25] and to military defense but assembles texts that pertain mostly to premodern literary genres, the majority being poems, and illustrates these with landscape paintings and photographs seems to present a paradox. In this essay, I will discuss how Dongnan lansheng straddles its apparently diverging ambitions: to propagate modern transportation and to cater to traditional genres and formats of travel culture. The visual impression of the book is dominated by photography; this circumstance is also accorded in the editors’ note and explained as resulting from the difficulty of reproducing paintings.[26] But, as I will argue, the editors carefully orchestrated the photographs and the accompanying texts throughout the book, and employed the specific qualities of the photographic medium to reconcile its potentially conflicting goals.

Moreover, the book not only reconciles conflicting aims, but it also obliquely addresses the armed conflicts that constituted an important factor in its inception. As stated earlier, the new roads and railways were to serve “the convenience for the military, the defense against bandits, and the enhancement of public security.”[27] These conflicts were suppressed by the narratives of elite travel in Dongnan lansheng, but, as I will show, they surface in a travelogue by Yu Dafu郁達夫 (1896–1945) and in an accompanying photograph.

Moving through the Landscape and Directing the Gaze

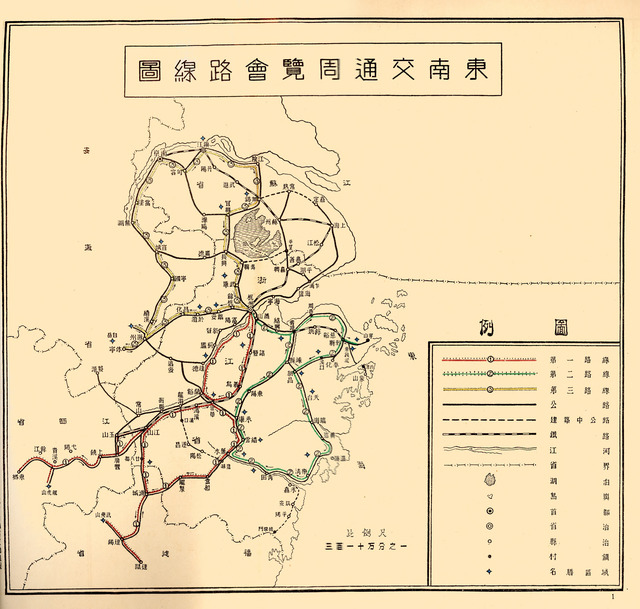

Fig. 2. “Map of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Routes,” Dongnan lansheng (1935), “General Introduction,” page 1. Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 2. “Map of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Routes,” Dongnan lansheng (1935), “General Introduction,” page 1. Courtesy Shanghai Library.According to the English preface, by Ye Qiuyuan 葉秋原 (1907–1948), the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province “invited people of repute to come to Chekiang to visit various places of interest and beauty. They were requested to write travelogues and poems, and to photograph and paint scenic spots along the route travelled.”[28] These people were organized in groups that traveled along one of the routes that are charted in a map in the opening section of Dongnan lansheng (figure 2).[29] The map shows three itineraries, all beginning and ending in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang Province, and indicates famous sites along the routes.

The first tour led south to Wuyishan, in Fujian Province, then into Jiangxi and back to Hangzhou along the Fuchun River. Tour two first headed west to Huangshan, in Anhui Province, then north to Nanjing and back along the Taihu. The third tour explored the eastern part of Zhejiang and its coastal region. In the subsequent chapters of Dongnan Lansheng, however, these basically circular routes are split up into more linear sequences that are linked to the course of roads and railways. The chapters have titles such as “Along the Nanjing–Hangzhou Highway and the Taihu Region,” “Along the Hangzhou–Huizhou Highway,” and “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, the Hangzhou–Guangfeng Highway, and the Fuchun River.” The logic of the tours is thus transformed into the image of a network of roads extending from Hangzhou, the political center of the province.

Although the separate parts of the book are named after highways, these remain largely unmentioned. They run underneath, however, as a thread that guides the experience of travel, as the texts and images are arranged in the sequence of travel along the itineraries indicated by the chapter titles. With few exceptions, the titles of the poems, travelogues, and images refer to specific places — the famous sites in the Southeast that readers were encouraged to seek out. These sites are for the most part not built structures but instead natural landscape formations: rocky cliffs, caves, waterfalls, mountain paths, streams, and rivers. They are grouped according to what might be called scenic areas, and these in turn are in most cases defined by mountains, such as Moganshan, Tianmushan, Beishan (North Mountain), Tiantaishan, and Yandangshan. The landscape of Zhejiang serves as the ground on which long-established practices of elite travel and related forms of literature, visual culture, and aesthetic appreciation could be reconceived under the conditions of modern means of transportation, image-making techniques, and academic fields.

The aestheticizing nature of the landscape representations is underscored by another structure in the book that intersects and interweaves with this grouping around specific mountains and, to a lesser degree, rivers. The texts and illustrations also follow a topical sequence; in the chapter on the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, for example, a sequence on mountain streams is followed by one on caves, another on mountain passes, and one on rivers. Within these topical sequences, texts with similar or even identical titles by different authors are assembled and complemented by photographs of related motifs and equally similar titles.

One of the most obvious instances of this editorial principle is a sequence of pages approximately in the middle of the chapter on the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad (figures 3–6). It begins with a page with two poems and one photograph bearing more or less the same title, “On the Way to North Mountain.” These are followed by photographs that seem to have been taken along the way; another poem, with the title “Setting out for North Mountain by Dawn”; and then a travelogue describing the visit to the Three Caves on North Mountain. This last text marks the beginning of a topical sequence focusing on the caves.

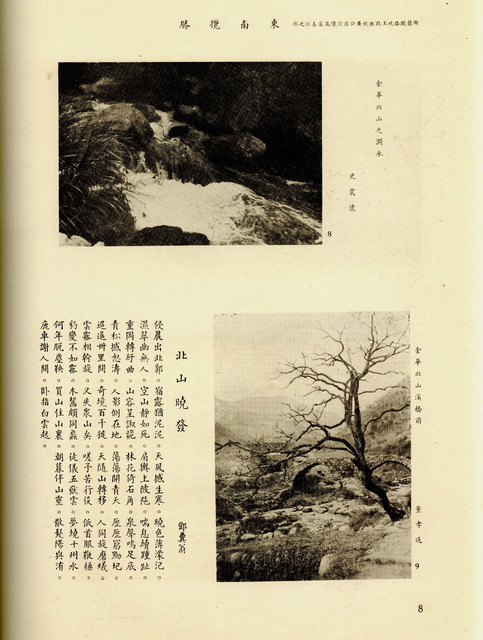

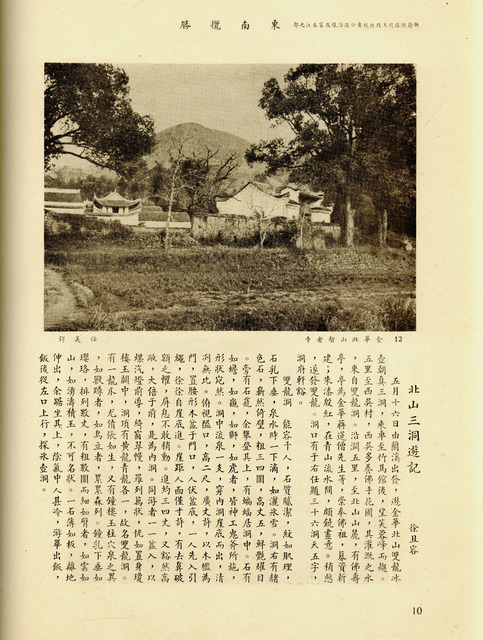

Fig. 3. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, the Hangzhou–Guangfeng Highway, and the Fuchun River,” page 7, with a photograph by Zeng Shirong, “On the Way to North Mountain,” and poems by Tang Erhe, “On the Road to North Mountain,” and Shen Yiliu, “On the Way to North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 3. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, the Hangzhou–Guangfeng Highway, and the Fuchun River,” page 7, with a photograph by Zeng Shirong, “On the Way to North Mountain,” and poems by Tang Erhe, “On the Road to North Mountain,” and Shen Yiliu, “On the Way to North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library. Fig. 4. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 8, with photographs by Shi Zhenhuai, “Creek in North Mountain, Jinhua,” and Dong Xiaoyi, “In front of the Bridge of North Mountain Stream, Jinhua,” and a poem by Deng Fenweng, “Setting out for North Mountain by Dawn.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

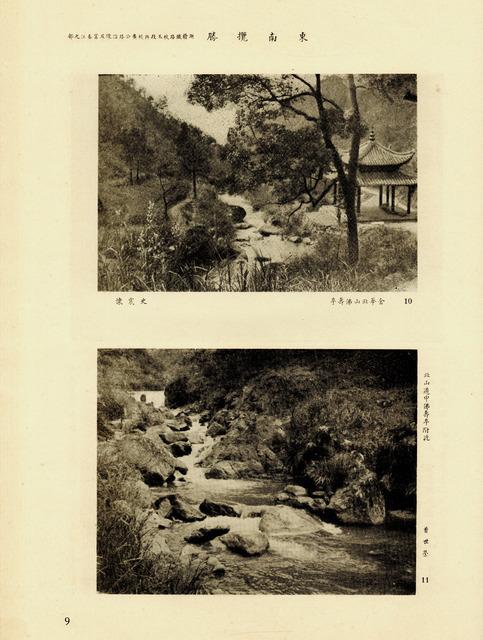

Fig. 4. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 8, with photographs by Shi Zhenhuai, “Creek in North Mountain, Jinhua,” and Dong Xiaoyi, “In front of the Bridge of North Mountain Stream, Jinhua,” and a poem by Deng Fenweng, “Setting out for North Mountain by Dawn.” Courtesy Shanghai Library. Fig. 5. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 9, with photographs by Shi Zhenhuai, “Buddha Longevity Pavilion at North Mountain, Jinhua,” and Zeng Shirong, “Near Buddha Longevity Pavilion on the Road to North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 5. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 9, with photographs by Shi Zhenhuai, “Buddha Longevity Pavilion at North Mountain, Jinhua,” and Zeng Shirong, “Near Buddha Longevity Pavilion on the Road to North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library. Fig. 6. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 10, with a photograph by Ren Mei’e, “Zhizhe Temple at North Mountain, Jinhua,” and the opening section of a travelogue by Xu Qierong, “Visiting the Three Caves at North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 6. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 10, with a photograph by Ren Mei’e, “Zhizhe Temple at North Mountain, Jinhua,” and the opening section of a travelogue by Xu Qierong, “Visiting the Three Caves at North Mountain.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.The poems are written in classical style, and in their content follow the conventions of classical landscape poetry as well. “On the Road to North Mountain” (“Beishan tu zhong” 北山途中), by Tang Erhe 湯爾和 (1878–1940),[30] a seven-syllable jueju,[31] is typical in this regard:

| 泉聲嵐氣雨無窮。 | Sounds of springs and mist from hills, rains without end |

| 身在清湘畫稿中 | Finding myself in a painting by Qingxiang[32] |

| 最愛滿山烏桕樹 | What I love most are mountains covered with tallow trees |

| 秋深映照滿溪紅 | In deep autumn they are mirrored, the streams all in red |

Site specificity is achieved by way of the title and through learned allusions, in this case the red leaves of the tallow trees, which are characteristic of the region and also mentioned in the second poem on the page, “On the Way to North Mountain” (“Beishan dao zhong” 北山道中), by Shen Yiliu 沈軼劉 (1898–1993). Both poems describe the subjective experience of being in a place. They respond to or create images that encapsulate certain characteristics of an environment, such as the flora, the topography, historical events that took place there, or the weather conditions.

This practice of place-related landscape poetry played an important role in the Chinese culture of travel; Richard Strassberg has remarked with regard to inscriptions engraved at certain sites that through this textualization, a place “became significant and was mapped onto an itinerary for other travelers.”[33] The poems in Dongnan lansheng equally serve to render the landscape coded and recognizable. They make the journey along the routes meaningful (an aspect of particular importance for formerly remote mountain or border regions such as those crossed by the new railway) or they enhance the importance of already well-known places by adding cultural layers on them and by directing the aesthetic response of future travelers.

The corresponding sequence of photographs, however, serves a different purpose (figures 3–6). In their captions, the photographs of mountain roads, rushing streams, small bridges, and pavilions are mapped onto the route with topographical precision, combining Pictorialism with documentation.[34] By way of the editorial arrangement within the book, they become a sequence that unfolds from the beginning of the road that runs along the banks of a stream into the depth of the photo and then ascends the mountain along the courses of streams that similarly lead the viewer’s gaze into the depth of the picture and the valley. Finally, the gaze is turning around to capture the image of a roadside temple, which has already been passed by. The sequence of similar compositions showing paths and streams leading uphill suggests the movement of the traveler — the future movement that she or he is about to make along the road — and the ongoing movement of the present progressive in the case of the roadside view of a temple. They do not direct the reader/viewer/future traveler’s impressionistic response to scenery or the situation of being on the road, but rather project their gaze on the road that is yet to be traveled or from the road, in views from an oblique angle toward scenic sites that are not portrayed but instead passed by and left behind.

Taken alone, photos such as Shi Zhenhuai’s 史震懷 “Buddha Longevity Pavilion on North Mountain, Jinhua” (figure 5), which shows generic landscape elements to be found anywhere in China, create a seemingly timeless, ideal landscape that is at the same time local and generalized, as is the case with the poem by Tang Erhe quoted above. But by placing Zeng Shirong’s 曾世榮 (1899–1996) close-up view of the same stream right beneath and giving it an almost identical title, both images are bound into a sequence. By directing the gaze along the courses of roads and waterways into spatial recession, the perspectival mode of vision that is pertinent to photography[35] is emphasized, as it serves to extend a continuous line of vision from the receding lines inside the image to the viewpoint in front of it. This effect is enhanced by the absence of human figures in the majority of the photographs. Instead of identifying with the figures in the images (a viewing convention that is employed in many Chinese landscape paintings, especially those relating to the theme of travel, and which is also at work in the ink paintings reproduced in Dongnan lansheng), the reader is invited to identify with the person behind the camera — that is, with the person who is actually or imaginatively about to move into the landscape along the paths.

The sequencing of photos with similar motifs with poems and travelogues on these motifs, which forms series within the chapters, deemphasizes the single site (the sheng 勝 in Dongnan lansheng) and emphasizes the experience of moving from one to the next (the lan 攬, or searching out, in the book title). This effect is heightened by the fact that the photographs are frequently very similar, whether in motif or in composition, and often remarkably unspectacular.

Equally important for achieving this effect is that the photographs were taken by different artists; they form a sequence that does not reflect a single person’s view of the landscape but rather a collective gaze, and a collective experience of traveling along those roads and paths. Through the medium of photography, a collective subject is formed whose experience of movement through the landscape constitutes the main narrative of the book. This experience is also shared with the authors of the poems and travelogues, whose texts likewise are variations on related motifs, regardless of whether or not the artists actually took the tour together. The individual photographs were reframed and orchestrated into a coherent whole in correspondence with the poems, travelogues, and paintings.[36] Together the different artistic media prefigured for the reader/viewer the experience of traveling through the famous mountains and along the great waterways of the Southeast, and each imparted its specific mediality on this anticipatory experience.

Motorized Travel and Shifting Temporalities

The travelogues in Dongnan lansheng relay the experience of travel through detailed descriptions of visits to specific places (normally not, though, the journey that brought the authors there); of their most important topographical features and built structures, comparing the sights encountered with historical and literary records; and of the corporeal, emotional, and aesthetic reactions the locations engendered in the visitor. They foreground the scenic sites that are the destinations of travel and the reception of the landscape. The aesthetic potential of the railway and motorized travel is notably disregarded, and the convenience of travel by train or bus is noted primarily in departure and arrival times. The newly constructed railroad and highways shaped modern leisure travel, but they apparently remained disconnected from local life and sightseeing, closing off the traveler from the environment that was still moving at a walking pace.

The premodern forms of travel on which the tourists relied as soon as they disembarked from the bus or train established a continuity of experience with that of earlier travelers. This also contributed to the relative continuity with the conventions of travel writing in the texts.[37] The collective movement through the landscape conveyed by the photographs and poems is proceeding at a slow speed, as those parts of the journeys that receive extended description were undertaken on foot or by sedan chair.

A notable exception in this regard is a travelogue by the modernist writer Yu Dafu, “The Steepness of Xianxia” (Xianxia jixian 仙霞紀險).[38] This text exemplifies how Dongnan lansheng was entangled with other travel-related publications of the mid-1930s. Originally Yu’s text was one of four short chapters in a travelogue titled “Brief Account of Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang” (Zhedong jingwu jilüe 浙東景物紀略),[39] which was commissioned in 1933 by the Hangzhou Railway Bureau for a book titled Zhedong jingwu ji: Hang-Jiang tielu daoyou congshu zhi yi (Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang: An Anthology of Travel Guides to the Hangzhou-Jiangshan Railway).[40] Although much narrower in scope and less sumptuous in its production, this anthology can be regarded as a precursor to Dongnan lansheng. Around the time it was published, in December 1933, “The Steepness of Xianxia” was also printed in two sequels in Shenbao.[41]

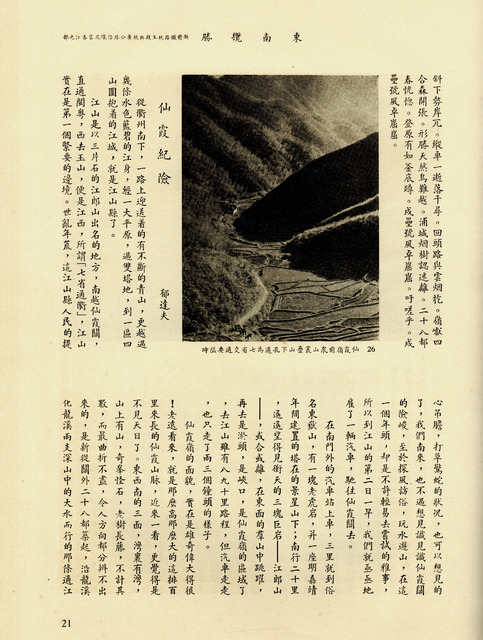

“The Steepness of Xianxia” describes an outing to Xianxialing, a mountain ridge that forms the natural border between the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangxi, and Fujian. In this prose text, written in the vernacular, the experience of motorized travel by car is brought to the fore. The perception of landscape is guided by the itinerary of the road: Yu describes geographical information on mountains seen along the road, a self-aggrandizing view over the landscape, and the speed of the car (“although we covered eighty or ninety li since leaving Jiangshan, driving in the car, it just took us something like two to three hours”). The self-confident tone gradually gives way to the loss of sense of direction as the car climbs winding mountain roads, each bend bringing different scenery into view. The climax is reached midway through the text, when the car has to drive beyond Xianxia Pass, and the author comes to the conclusion that whoever wants to “see the winding of the landscape, try out the twisting of a road, test his fate, tread the line between life and death, and go to the utmost risk has to go to Xianxialing,” especially on the new motor road.[42]

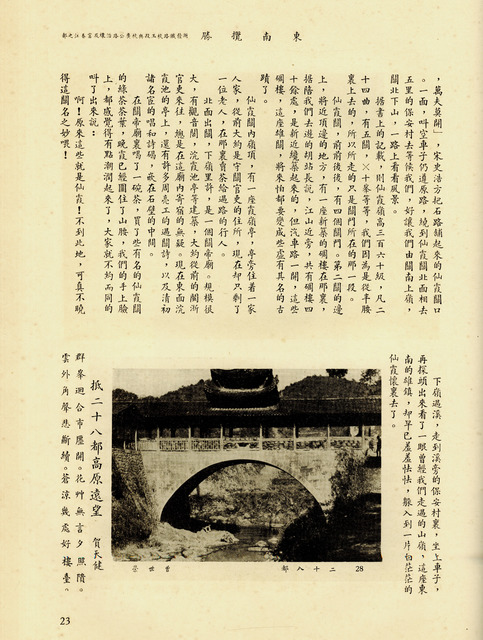

Then the narrative slows down; the group climbs back by foot over the fortified Xianxia Pass, a local guide appears, and historical information is imparted. But the visit is still dominated by the impression of modern transportation: Yu speculates that with the opening of new motor roads, the pass itself and the more than forty newly built watchtowers (diaolou 碉樓) in the vicinity will become obsolete (literally, “their names will become meaningless,” xu you qi ming 虛有其名) and turn into “ancient relics” (guji 古蹟). The report ends with the departure of the car; the traveler turns his head to take one last look at the mountain pass now hidden in clouds.[43] The movement through the landscape that structures Yu Dafu’s text, driving upward along steep mountain roads, glimpsing places of particular beauty or historical note, and glancing backward as the movement continues, corresponds closely to the arrangement of the photographs in Dongnan lansheng.

Two of the three photographs that illustrate the Dongnan lansheng edition of Yu’s text show views of valleys taken from a high vantage point, most likely from one of the steep roads leading up the mountain ridge of Xianxialing. One of them (figure 7), annotated as “The mountains below Xianxialing are dense and layered; the road at the foot of the mountains is a strategic thoroughfare connecting seven provinces,” is credited to the magazine Shidai (The Modern Miscellany) in the table of contents, but was probably taken by Chen Wanli (陳萬里, 1892–1969).[44] Chen traveled to Xianxialing with Yu Dafu,[45] and a photograph in the railroad anthology Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang that is strikingly similar to the one discussed here is attributed to him.[46] The picture was therefore probably taken during the hair-raising car ride up the ridge so vividly described in Yu’s text. The third photograph printed with Yu’s text in Dongnan lansheng, taken by Zeng Shirong, shows the monumental structure of a roofed bridge (figure 8). Although it is apparently neither the fortified mountain pass nor a diaolou, the image connects with the text, and the bridge becomes one of the unmodern structures that will be superseded by modernization and turn into an “ancient relic.” Tellingly, the photographer Zeng Shirong himself was an agent of this change: He was a railroad engineer serving at the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad Bureau.[47] Of all the authors, he contributed the second-largest number of photographs to Dongnan lansheng.[48]

Fig. 7. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 21, with a travelogue by Yu Dafu, “The Steepness of Xianxia,” and a photograph from Shidai magazine (by Chen Wanli?), “The Mountains below Xianxialing are Dense and Layered; the Road at the Foot of the Mountains Is a Strategic Thoroughfare Connecting Seven Provinces.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 7. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 21, with a travelogue by Yu Dafu, “The Steepness of Xianxia,” and a photograph from Shidai magazine (by Chen Wanli?), “The Mountains below Xianxialing are Dense and Layered; the Road at the Foot of the Mountains Is a Strategic Thoroughfare Connecting Seven Provinces.” Courtesy Shanghai Library. Fig. 8. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 23, with a travelogue by Yu Dafu, “The Steepness of Xianxia,” a photograph by Zeng Shirong, “Ershibadu,” and a poem by He Tianjian, “Arriving at the Plateau of Ershibadu and Gazing into the Distance.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 8. Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad . . .,” page 23, with a travelogue by Yu Dafu, “The Steepness of Xianxia,” a photograph by Zeng Shirong, “Ershibadu,” and a poem by He Tianjian, “Arriving at the Plateau of Ershibadu and Gazing into the Distance.” Courtesy Shanghai Library.But the picture is more complicated than it appears at first sight. A comparison of the editions of “The Steepness of Xianxia” in Dongnan lansheng and Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang with the version printed in the newspaper Shenbao shows that a significant portion of Yu’s text was omitted in the two government-sponsored books. The Shenbao version contains the account of an abortive visit to Ershibadu, a village just south of Xianxia Pass. The travelers find it deserted, inhabited by only a few traumatized and ghostlike figures refusing to speak[49] and soldiers. One of the soldiers informs them that the village had been deserted for more than a year, and that there had been (unspecified) rumors the night before. Deeply frightened, Yu and his fellow travelers decline the offer of a meal and leave immediately.[50] Probably this passage was omitted in Dongnan lansheng and Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang because its evocation of armed conflict was detrimental to the two books’ propagandistic aims of praising the beauty of the Zhejiang landscape and encouraging travel there. This suppressed conflict is, however, not entirely eliminated; it resurfaces in Zeng Shirong’s photograph of the roofed bridge.

One Photograph and Two Views of a Roofed Bridge

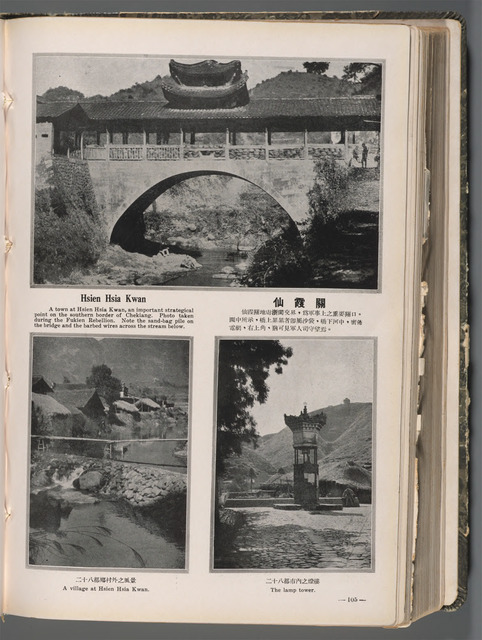

Zeng Shirong’s photograph, titled “Ershibadu” in Dongnan lansheng, had been published earlier, albeit anonymously (figure 9). It dominates a page dedicated to the Xianxia Pass in another monumental publication, China as She Is: A Comprehensive Album, published by the Liangyou Publishing House in 1934.

Fig. 9. Wu Liande, ed. China as She Is: A Comprehensive Album (Shanghai, 1934), page 105, with photographs of Xianxia Pass by anonymous photographers. Courtesy Widener Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 9. Wu Liande, ed. China as She Is: A Comprehensive Album (Shanghai, 1934), page 105, with photographs of Xianxia Pass by anonymous photographers. Courtesy Widener Library, Harvard University.China as She Is is at the same time more comprehensive and more condensed than Dongnan lansheng. It is based on the collaboration of six editors and four photographers.[51] According to the foreword, the photographs reproduced are the result of an extensive tour by a selected group from the Liangyou staff through every province of China. The tour was widely publicized in the Liangyou pictorial, and photographs taken during the journey were reproduced in several issues. For the “comprehensive album” that China as She Is claims to be in its subtitle, the choice of illustrations followed a standardized scheme in form and content. In the foreword, the editors claim for themselves “a purely objective standard” and as their aim “exposition and interpretation — not propaganda.”[52] Accordingly, the authors’ names for the single photographs are not given and their individuality is suppressed.

The book is structured according to provinces, and although some of the photographs show modern cities, temple sculptures, social customs, and even roads, the vast majority are of landscapes — namely, the famous mountains and big rivers of the provinces. A maximum of nine pages (accorded to the capital city of Nanjing) and more often one page was allocated to chosen places within each province; two to four photographs were printed on each page, with brief captions in Chinese and English. Thus the most representative sites and the most representative views of those sites were selected, standardized, and reinforced, and the information that was deemed most relevant was filtered.[53]

In China as She Is, the photo of the roofed bridge becomes the representative image of Xianxia Pass, with two photographs of the village of Ershibadu printed below (figure 9). Consistent with the practice throughout the atlas, no author is named. However, the caption gives some information that links it to the discomforting account of the visit to Ershibadu in Yu Dafu’s travelogue. Because the English caption is an abbreviated version of the Chinese text, I translate the latter here:

Xianxia Pass is on the border of Zhejiang and Fujian Provinces; it is an important strategic point. As can be seen in the image, sandbags are piled up on the bridge, and across the river there is a dense array of electrical wires. In the upper right corner, soldiers can be seen standing guard.[54]

The English caption gives the additional information that the photograph was taken at the time of the Fujian Rebellion.[55] During this uprising, which lasted from November 20, 1933, to January 22, 1934, Fujian Province declared its independence from the Nanjing government and a Revolutionary People’s Government was formed.[56] In the quick suppression of the rebellion, the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad played a crucial role, as it enabled the central government to swiftly dispatch soldiers to the Zhejiang–Fujian border,[57] which is formed by Xianxialing. The railroad thus fulfilled the strategic task that was a major objective behind its construction, and its effectiveness is indirectly demonstrated by the photograph.

The caption in China as She Is also gives the historical background of Yu Dafu’s anecdote about the deserted village, in which he vividly describes war-inflicted bleakness, but does not mention which conflict actually caused the situation. In fact, Yu’s visit must have more or less coincided with the beginning of the Fujian Rebellion.[58] The “rumors” mentioned by the soldier in his account apparently referred to that incident. The year before, in September 1932, nearby Pucheng had been occupied by Communist forces; according to a report in Shenbao, military units were sent to Ershibadu to protect the Zhejiang border.[59] This explains why Ershibadu had already been deserted, as Yu was told by the soldier.

In Dongnan lansheng, the same photograph is reproduced in smaller scale and without any further information; because any hint of military conflict is excised from the text, the electrical wires, sandbags, and soldiers might easily be overlooked. Instead, the imposing structure of the roofed bridge appears to be one of those infrastructural elements that are about to become superfluous with the advent of motorized travel and will soon turn into “ancient relics,” according to Yu Dafu’s statement on the same page.[60] In China as She Is, the image refers to a specific historical moment during the Fujian Rebellion and the site’s strategic role therein; in Dongnan lansheng, it becomes a glimpse into a past that is about to vanish as the movement that produces the image will pass by the building, spatially and temporally. With these two framings of the photograph, the transformation of the landscape by modern infrastructure and by the speed of engineered transportation is doubly projected onto the bridge: as an effect brought about by armed conflict and as an effect of modernization that turns the bridge into a relic of the past.

Monuments and Movement

This difference in the framing of Zeng Shirong’s image is symptomatic of the editorial approaches underlying the two publications. Both books are presented as the result of a collective experience. In China as She Is, even the authorship of the photographs is collectivized; in Dongnan lansheng, it is through the arrangement of topical/geographical sequences and the mapping of texts and image titles onto shared itineraries that the collective authorship is formed. But whereas in China as She Is the photographs are claimed to be objective documentations of the most representative sights (in turn, of the most representative sites) of each province, in Dongnan lansheng very similar pictures are used to convey the subjective experience of traveling through the landscape.

Thierry de Duve’s differentiation between “snapshot” and “time exposure” in what he calls the “paradox of photography” is helpful here to conceptualize the different functions of the photographs in the two books. De Duve describes two ways of perceiving a photograph, either as snapshot/event or as time exposure/picture, which “coexist in our perception of any photograph. . . . [T]hey set up a paradox, which resolves in an unresolved oscillation of our psychological responses toward the photograph.”[61] The snapshot refers to life as “process, evolution, diachrony”; the time exposure “deals with an imaginary life that is autonomous, discontinuous, and reversible, because this life has no location other than the surface of the photograph.”[62] He assigns different modes of temporality to the respective aspects of the photographic paradox:

[W]e can describe [the photographic paradox] as a double branching of temporality: (1) in the snapshot, the present tense, as hypothetical model of temporality, would annihilate itself through splitting: always too early to see the event occur at the surface, and always too late to witness its happening in reality; and (2) in the time exposure, the past tense, as hypothetical model, would freeze in a sort of infinitive, and offer itself as the empty form of all potential tenses. [63]

Although de Duve uses the length of exposure to define the constituents of the paradox, he also argues that they exist in our perception of any photograph, regardless of the actual exposure time. The temporality assigned to a photograph is also determined by exterior factors, most notably during the moment of reception.

In Zeng Shirong’s photo of the bridge at Xianxia Pass, the branching of temporality is an effect of the different framings in the respective publications: In China as She Is, the bridge becomes a monument, and the past moment of the Fujian Rebellion is halted in what Thierry de Duve has described as “time exposure.” The “process, evolution, diachrony,” which he identifies in the snapshot, is at work in the sequential arrangement of photos along the roads, valleys, and streams of Zhejiang in Dongnan lansheng. Their temporality becomes fluid in the latter case by their insertion into a narrative of travel and movement.

The temporal fluidity in the photographic illustrations in Dongnan lansheng becomes most obvious in the chapter “Along the Hangzhou-Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, the Hangzhou–Guangfeng Highway, and the Fuchun River.” As described above, the sequencing of photos with similar motifs together with poems and travelogues and the ensuing direction of the gaze along the courses of roads and waterways invite the reader to identify with the person behind the camera. The effect is similar to the subjective viewpoint exemplified by the tracking or traveling shot in film, where the camera mounted on a vehicle embodies the eye of the driver/passenger moving through the landscape.[64]

Annette Deeken has observed that images of roads and railroad tracks are frequently read as stills from a traveling shot, as the viewer projects her or his experience of movement onto them.[65] Dongnan lansheng contains one picture that combines such a mobilized image with the experience of spectatorship in a straightforward way. This image is not one of the regular illustrations showing the landscapes of Zhejiang; it is one of the advertisements that are also in the book, a page-size ad for the Ciné-Kodak Eight, an 8 mm camera (figure 10). The image shows a group of people, apparently Americans, gazing at a windowlike screen displaying snow-clad mountains.[66] Because the image represents a film still of a traveling shot, it is mobilized by the onlooker, similar to what Deeken describes for photos of railroad tracks. The accompanying text states that “if you want to keep the famous sites you visited, nothing is better than shooting your own film.” Paradoxically for a photobook, out of the numerous advertisements in Dongnan lansheng that are related to travel and image making — by international corporations such as Shell, Dunlop, Agfa, and Kodak as well as by domestic travel, telephone, banking, and printing companies — the one that seems to best capture the intention of the editors is this one for an apparatus producing moving images.

Fig. 10. Advertisement for the Ciné-Kodak Eight, an 8 mm camera, in Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Nanjing–Hangzhou Highway and the Taihu,” between pages 4 and 5. Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 10. Advertisement for the Ciné-Kodak Eight, an 8 mm camera, in Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Nanjing–Hangzhou Highway and the Taihu,” between pages 4 and 5. Courtesy Shanghai Library. Fig. 11. Gong Zhuxian, “The Great Buddha at the Great Buddha Temple, Nine Visitors in His Palms,” Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Fuzhou Highway and the Shanghai–Lin’an Highway,” page 15. Courtesy Shanghai Library.

Fig. 11. Gong Zhuxian, “The Great Buddha at the Great Buddha Temple, Nine Visitors in His Palms,” Dongnan lansheng (1935), “Along the Hangzhou–Fuzhou Highway and the Shanghai–Lin’an Highway,” page 15. Courtesy Shanghai Library.The experience of being in a place and actually exploring a scenic site is not absent in Dongnan lansheng. As discussed above, the poems and travelogues describe in classical style the aesthetic, emotional, and physical responses to the climbs onto mountains, views from peaks, descents into caves, and boating tours on rivers. Most of the ink paintings also refer to the act of viewing through the inclusion of sightseeing travelers, and so do several of the photographs. Although the majority of the photographs are uninhabited, at the moment of arrival at a specific destination the authors are shown enjoying the waves on the shores of Taihu, descending into caves, posing on the palms of the Great Buddha of Xinchang (figure 11), or inside an ancient bronze cauldron (huo 鑊).

These personalized moments of experiencing the landscape and ancient monuments are only punctuating the book before the journey through the pages continues. However, the self-confident manner in which the authors pose on the Buddha’s palms conveys a hedonistic attitude that can be seen as one element tying together the characteristics of the book that I have earlier described as forming a paradox: the modernizing rationale underlying the state-sponsored infrastructure projects and the seemingly traditional formats of its texts and images. These potentially conflicting aspects are reconciled in the editorial arrangement of the photographs. In the visual narrative unfolding on the pages of Dongnan lansheng in the medium of photography, the ultimate goal is travel itself, the movement along the new roads and railways built by the Construction Bureau of Zhejiang Province, and sightseeing at the places reached by these roads. Readers are invited to identify themselves with the authors and photographers traveling along mountain paths, driving across the ridges of Xianxialing, and climbing on monuments from a bygone era.

The intended reader of Dongnan lansheng was educated, well-to-do, a Shanghai or Hangzhou resident, male, modern, and elitist. He would not be distracted by the imminent military conflicts that precipitated road construction, but instead would concentrate on speeding past or reveling in the beauty of Southeast China’s mountains and waters.

Juliane Noth is a research associate at the Institute of East Asian Art History, Heidelberg University. She is the author of Landschaft und Revolution: Die Malerei von Shi Lu (2009) and coeditor of several volumes, and has published widely on the art and visual culture of Republican and socialist China. She recently completed the manuscript for her second book, In Search of the Chinese Landscape: Ink Painting, Travel, and Transmedial Practice, 1928–1936.

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the conference “Portable Landscapes,” at Durham University in July 2015, and in the panel “Mediating Landscapes in Modern and Contemporary China,” at the AAS Annual Conference 2017 in Toronto. Special thanks go to my fellow panelists, Paola Iovene, Catherine Stuer, Yi Gu, and Anup Grewal, for inspiring discussions and intellectual input.

Notes

“Jiang Weiyuanzhang ling choubei Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui” 蔣委員長令籌備東南交通周覽會 (Council Chairman Jiang gives order to prepare a Southeastern Infrastructure Tour), Shenbao, February 18, 1934: 13.

On road construction under the auspices of the NEC, see William C. Kirby, “Engineering China: Birth of the Developmental State, 1928–1937,” in Becoming Chinese: Passages to Modernity and Beyond, ed. Wen-hsin Yeh (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2000), 145–46; Jürgen Osterhammel, “‘Technical Co-operation’ Between the League of Nations and China,” in Modern Asian Studies 13, no. 4 (1979): 674–75; on road construction in Zhejiang Province, see Noel R. Miner, “Chekiang: The Nationalists’ Effort in Agrarian Reform and Construction, 1927–1937” (PhD diss., Stanford University, 1973), 233–43.

“Jiang Weiyuanzhang ling choubei Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui”; “Jiaotong anquan yundong: Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui bennian liuyue zhong juxing” 交通安全運動:東南交通周覽會本年六月中舉行 (Traffic Security Campaign: The Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Will Take Place This Year in June), Shenbao, February 22, 1934: 12.

By late April 1934, the tour was announced for autumn, now with a duration of one month; “Jiang ling Zeng Yangfu zhuban Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui” 蔣令曾養甫主辦東南交通周覽會 (Jiang gives order to Zeng Yangfu to organize the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour), Shenbao, April 26, 1934: 9. In early May, the start of the tour was scheduled for October 10, the National Day of the Republic; “Zhe Jianting choubei Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui” 浙建廰籌備東南交通周覽會 (The Zhejiang Construction Bureau prepares the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour), Shenbao, May 8, 1934: 7.

“Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui zanhuan juxing” 東南交通周覽會暫緩舉行 (The Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Is Temporally Suspended), Shenbao, September 2, 1934: 12.

“Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui chou yin Dongnan lansheng” 東南交通周覽會籌印《東南攬勝》 (The Southeastern Infrastructure Tour prepares to print In Search of the Southeast), Shenbao, August 23, 1934: 12.

“Wu Zhihui deng you Tianmushan” 吳稚暉等游天目山 (Wu Zhihui and others visit Tianmushan), Shenbao, April 1, 1934: 11; “Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui xingcheng” 東南交通周覽會行程 (The Itinerary of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour), Shenbao, April 6, 1934: 7.

“Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui Huangshan sheying jiang kai zhanlanhui” 東南交通周覽會黃山攝影將開展覽會 (An Upcoming Exhibition of Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Huangshan Photography), Shenbao, June 27, 1934: 13.

“Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui zuori zhanlan chengji zai Baxianqiao Qingnianhui jiu lou” 東南交通周覽會昨日展覽成績在八仙橋青年會九樓 (An Exhibition of the Southeastern Infrastructure Tour Opened Yesterday at the Youth League at Baxianqiao), Shenbao, July 20, 1934: 11.

Zeng Yangfu 曾養甫, “Xu” 序 (Preface), in Dongnan lansheng 東南攬勝 (In Search of the Southeast), ed. Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui xuanchuan zu (Quanguo jingji weiyuanhui Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui, 1935), unpaginated; Y. Weitan Yih (Ye Qiuyuan葉秋原), “In Search of the Southeast,” ibid., unpaginated. According to a Shenbao report, Jiang Jieshi had personally entrusted Zeng with the organization of the tour; “Jiang Weiyuanzhang ling choubei Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui,” 13.

The Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railway was the core infrastructural project realized in Zhejiang by the nationalist government during the Nanjing decade. It was initiated by Zhang Renjie 張人傑 (1877–1950) during his tenure as governor of Zhejiang, from 1928 to 1930, and linked the Shanghai–Hangzhou Railway with one of the country’s main lines, the Hankou–Guangzhou line. Its first section, from the southern bank of the Qiantangjiang near Hangzhou (which is located north of the river) to Lanxi, was built between 1930 and 1932; the second section, from Jinhua to Yushan across the Jiangxi border, opened for traffic two years later. The connection between Yushan and Nanchang was completed in 1935. The Qiantangjiang Bridge, constructed between 1934 and 1937, had two tiers, one for motor traffic and one for the railroad. With its completion, the Shanghai–Hangzhou line and the Zhejiang–Jiangxi line were connected. The bridge survived for only three months after its opening, in September 1937; it was destroyed to prevent Japanese troops from crossing the Qiantang River in December and reopened only in 1947. Miner, “Chekiang,” 243–55; Ding Xianyong, “Firedrake: Local Society and Train Transport in Zhejiang Province in the 1930s,” in Transfers 3, no. 3 (2013): 32–33; Xiao Hui 曉輝, “Zeng Yangfu yu Qiantangjiang daqiao” 曾養甫與錢塘江大橋 (Zeng Yangfu and the Qiantang River Bridge), Wenshi chunqiu (All about literature and history), no. 3 (1999): 73.

Zeng, “Zhe sheng jianshe dangqian zhi liang da renwu” 浙省建設當前之兩大任務 (Two Major Tasks in the Current Construction of Zhejiang Province), Zhejiang sheng jianshe yuekan (Zhejiang Province Construction Monthly) 5, no. 9 (1932): 4–5; idem, “Jiansheting zhi zeren” 建設廳之責任 (The Responsibilities of the Bureau of Construction), Zhejiang sheng jianshe yuekan 5, no. 8 (1932): 3–4; idem, “Zhejiang jianshe shiye zhi huigu jiqi zhanwang” 浙江建設事業之回顧及其展望 (Reconstructing Zhejiang: Past and Future), Shishi yuebao (Historical Facts Monthly) 12, no. 1 (1935): 90–92; Ding, “Firedrake,” 33.

Kuiyi Shen, “Scholar, Official, and Artist Ye Gongchuo,” in Elegant Gathering: The Yeh Family Collection, exhibition catalogue (San Francisco: Asian Art Museum Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture, 2006), 21–33.

Miriam Gross, “Flights of Fancy from a Sedan Chair: Marketing Tourism in Republican China, 1927–1937,” Twentieth-Century China 36, no. 2 (July 2011): 135–37.

The full list of names: Ye Gongchuo, Xu Shiying, Huang Yanpei, Jiang Weiqiao, Xia Jingguan, Huang Binhong, Lin Yutang, Yu Dafu, Pan Guangdan, Wang Jiyuan, Quan Zenggu, Shao Xunmei, Jiang Xiaopeng, Wang Yachen, Yu Jianhua, Chen Wanli, Hong Shen, Zhao Shuyong, Ye Qiuyuan, Guo Butao, Ye Qianyu, Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhenyu, and Wang Yingbin. Among these, Huang Yanpei, Huang Binhong Yu Dafu, Yu Jianhua, Chen Wanli, and Guo Butao contributed text to the book. Ye Qianyu, Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhenyu, Shao Xunmei, and Lin Yutang were editors of Shidai; see Shen, “A Modern Showcase: Shidai (Modern Miscellany) in 1930s Shanghai,” Yishuxue Yanjiu (Journal of Art Studies) 12 (2013): 129–70.

On Lüxing Zazhi, see Madeleine Yue Dong, “Shanghai’s China Traveler,” in Everyday Modernity in China, eds. Madeleine Yue Dong and Joshua L. Goldstein (Seattle and London: Washington University Press, 2006), 195–226; Wang Shuliang, et al., Zhongguo xiandai lüyou shi, 127–39.

Zhao Shuyong 趙叔雍, “Di yi xian youlan riji” 第一線遊覽日記 (Diary of Travels Along the First Route), Lüxing Zazhi (The China Traveler) 8, no. 7 (1934): 5–23; no. 8 (1934): 23–39.

Wuhan Xinwen Sheyingshe 武漢新聞攝影社 (Wuhan Press Photography Society), “Hubei gonglu jianshe jinkuang. Highway construction in Hupeh,” in Liangyou 102 (1935): 34–35; Huang Jianhao, photographer, “Nanbei jiaotong de mingmai. Linking North and South of China with a Railway,” in Liangyou 118 (1936): 40–41; “Jiji gangong xingzhu zhi Qiantangjiang da tieqiao. Construction Work on the Great Bridge Spanning the Chien-tang River in Rapid Progress,” in Liangyou 121 (1936): 32–33.

Wu Liande 伍聯德 et al., eds., Zhongguo daguan: Tuhua nianjian 1930 中國大觀:圖畫年鑑 (The Living China. A Pictorial Record 1930) (Shanghai: The Liang You Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., 1930).

Wu Liande, ed., Zhonghua jingxiang: Quanguo sheying zongji 中華景象:全國攝影總集 (China as She Is: A Comprehensive Album) (Shanghai: The Liang You Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., 1934).

Lynne Kirby, Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), 21–24, 36–42; Susan Danly, “Introduction,” in The Railroad in American Art: Representations of Technological Change, eds. Susan Danly and Leo Marx (Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 1988), 5–8.

Georges-Marie Haardt and Louis Audouin-Dubreuil, La Croisière Noire: Expédition Citroën Centre-Afrique (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1927); Georges LeFèvre, La Croisière Jaune: Expédition Citroën Centre-Asie. Troisième Mission Haardt-Audouin-Dubreuil (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1933).

One important agency for Japanese imperialism in Manchuria was the Southern Manchurian Railway Company; photobooks on Manchuria typically contrast depictions of traditional lifestyles with images of railroads, aircraft, and steamships representative of (Japanese) modernity — for example, in Kimura Ihee 木村伊兵衛, Ōdō rakudo 王道楽土 (Tokyo: Arusu, 1943). For an overview on such photobooks, see Martin Parr and Wassink Lundgren, eds., The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present, exhibition catalogue (New York: Aperture, 2015). See also Kari Shepherdson Scott, “Conflicting Politics and Contesting Borders: Exhibiting (Japanese) Manchuria at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933–34,” in Journal of Asian Studies 74, no. 3 (August 2015), 539–64.

Kirby, “Engineering China,” 138; Miner, “Chekiang,” 230–31; Sabine Dabringhaus, Territorialer Nationalismus in China: Historisch-geographisches Denken, 1900–1949 (Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2006), 195–96.

“Liyan” 例言 (Introduction), in Dongnan lansheng, unpaginated. The editors specifically refer to the difficulties in reproducing long handscrolls and large-size canvases.

“Jiang Weiyuanzhang ling choubei Dongnan jiaotong zhoulanhui,” 13.

Dongnan lansheng, “Zhe-Gan tielu Hang-Yu duan yu Hang-Guang gonglu yanxian ji Fuchunjiang zhi bu” 浙贛鐵路杭玉段與杭廣公路沿線及富春江支部 (Along the Hangzhou–Yushan Section of the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Railroad, the Hangzhou–Guangfeng Highway, and the Fuchun River), 7.

Cf. Richard Bodman and Shirleen S. Wong, “Shih,” in The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, vol. 1, ed. William Nienhauser, Jr. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 688, on the structure of jueju poems and the expression of landscape.

Richard E. Strassberg, Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1994), 6.

On pictorialist photography in Republican China, see Richard K. Kent, “Early Twentieth-Century Art Photography in China: Adopting, Domesticating, and Embracing the Foreign,” in Trans Asia Photography Review 3, no. 2 (2013), accessed September 8, 2015, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7977573.0003.204; and idem., “Fine Art Photography in Republican Period Shanghai: From Pictorialism to Modernism,” in Bridges to Heaven: Essays in East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong, vol. 2, eds. Jerome Silbergeld, et al. (Princeton: P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, in association with Princeton University Press, 2011), 849–74.

See, for example, Peter Galassi, Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography, exhibition catalogue (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1981), 12.

In a similar vein, Timothy J. Shea has recently discussed how the concept of “art photography” was popularized in the late 1920s and early 1930s through the framings in Liangyou; Shea, “Re-framing the Ordinary: The Place and Time of ‘Art Photography’ in Liangyou, 1926–1930,” in Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926–1945, eds. Paul G. Pickowicz, et al. (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013), 45–67, esp. 46–51.

For a comprehensive discussion of the youji genre, see Marion Eggert, Vom Sinn des Reisens. Chinesische Reiseschriften vom 16. bis zum frühen 19. Jahrhundert (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2004).

Yu Dafu 郁達夫, “Xianxia jixian” 仙霞紀險 [The Steepness of Xianxia] in Dongnan lansheng, “Zhe-Gan tielu . . . zhi bu,” 21–23. Much has been written on Yu Dafu as a major modern Chinese writer, with a focus on his fictional and autobiographical works; among recent English-language studies are Kirk A. Denton, “Romantic Sentiment and the Problem of the Subject: Yu Dafu,” in The Columbia Companion to Modern East Asian Literature, ed. Joshua Mostow (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 378–84; Lydia Liu, Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture, and Translated Modernity, 1900–1937 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995), 143–49; Janet Ng, The Experience of Modernity: Chinese Autobiography of the Early Twentieth Century (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003), 69–69; Shu-mei Shih, The Lure of the Modern: Writing Modernism in Semi-Colonial China, 1917–1937 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2001), 115–23; for a discussion of Yu’s travel writing, see Zhu Defa 朱德發, Zhongguo xiandai jiyou wenxue shi 中國現代紀遊文學史 (A History of Modern Chinese Travel Writing) (Jinan: Shandong Youyi chubanshe, 1990), 165–80.

“Brief Account of Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang” has been anthologized in various collections of Yu’s travel writings, beginning with Jihen chuchu 屐痕處處 (Scattered Traces of My Wooden Sandals) in 1934. Cf. Yu Dafu youji ji 郁達夫遊記 (Collected Travelogues of Yu Dafu) (Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin chubanshe, 1982), 49.

Yu, “Zhedong jingwu jilüe” 浙東景物紀略 (Brief Account of Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang), in Zhedong jingwu ji. Hang-Jiang tielu daoyou congshu zhi yi 浙東景物紀 杭江鐵路導遊叢書之一 (Accounts of Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang: An Anthology of Travel Guides to the Hangzhou–Jiangshan Railway) (Hangzhou: Tielu ju, 1933), 31–49.

Yu, “Xianxia jixian,” Shenbao, Ziyoutan, December 13, 1933: 15, and December 14, 1933: 17.

Yu, “Xianxia jixian,” in Dongnan lansheng, “Zhe-Gan tielu . . . zhi bu,” 22.

Chen Wanli was one of the most prominent and influential amateur photographers in Republican China; Chen Shen 陳申 and Xu Xijing 徐希景, Zhongguo sheying yishushi 中國攝影藝術史 (A History of Chinese Photography) (Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2011), 171–80.

Yu, “Xianxia jixian (xu)” 仙霞紀險(續), Shenbao, Ziyoutan, December 14, 1933: 17.

Chen Wanli’s photograph in the 1933 publication bears the title “Looking South from Xianxialing.”

“Zeng Shirong” 曾世榮, www.huaxia.com, accessed October 7, 2015, http://search.huaxia.com/s.jsp?iDocId=501088.

Not less significantly, the most images were contributed by Ren Mei’e 任美鍔 (1913–2008), a former student of geography who was still in his early twenties at the time of the publication of Dongnan lansheng; he earned a doctorate from the University of Glasgow in 1939 and later became one of China’s most eminent geographers (Inka Bianca Hausherr, Die Entwicklung der chinesischen Geographie im 20. Jahrhundert: ein disziplingeschichtlicher Überblick [Bremen: Universität Bremen, Institut für Geographie, 2003], 30).

Yu, “Xianxia jixian (xu),” Shenbao, December 14, 1933: 17; Yu, “Zhedong jingwu jilüe,” in Yu Dafu zuopin jingdian 郁達夫作品經典 (Selected Works of Yu Dafu), 4 vols., ed. Yang Zhansheng (Beijing: Zhongguo huaqiao chubanshe, 1998), vol. 3, 265.

This claim is contradicted by the photograph of the roofed bridge taken by Zeng Shirong, who was not listed among the contributors of China as She Is.

The chapters on each province begin with an overview of the geography, population, local products, communications and major cities.

On the Fujian Rebellion, see Lloyd Eastman, The Abortive Revolution: China under Nationalist Rule, 1927–1937, 3rd edition (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 1990), 85–139.

Another travelogue by Yu Dafu, “Itineraries of a Short Journey Along the Hangzhou–Jiangshan Line,” was also published in the Hangzhou Railway Bureau publication Scenic Sites in Eastern Zhejiang. Describing the first part of the journey ultimately leading to Ershibadu, it is in the form of a diary and dated November 9 to 15, 1933. The last entry is thus just five days before the outbreak of the Fujian Rebellion, on November 20. Yu, “Hang-Jiang xiaoli jicheng” 杭江小歷紀程, in Yu Dafu zuopin jingdian, vol. 3, 236–54.

“Minfei gongxian Pucheng, Zhe sheng bianfang gaoji 閩匪攻陷浦城浙省邊防吿急,” Shenbao, September 26, 1932: 4.

Yu, “Xianxia jixian,” in Dongnan lansheng, “Zhe-Gan tielu . . . zhi bu,” 23.

Thierry de Duve, “Time Exposure and Snapshot: The Photograph as Paradox,” in Photography Theory, The Art Seminar, ed. James Elkins (New York and London: Routledge, 2007), 109–110.

Tom Gunning, “Traveling Shots: Von der Verpflichtung des Kinos, uns von Ort zu Ort zu bringen,” in Traveling Shots: Film als Kaleidoskop von Reiseerfahrungen, eds. Winfried Pauleit, et al. (Berlin: Bertz + Fischer, 2007), 21–27; Annette Deeken, “Travelling: mehr als eine Kameratechnik,” in Bildtheorie und Film, eds. Thomas Koebner and Thomas Meder with Fabienne Liptay (München: edition text + kritik, 2006), 297–315.

This choice of motif was not accidental; it was tailored to the travel theme of Dongnan lansheng; an advertisement for the Ciné-Kodak Eight in Liangyou shows the spectators watching a self-recorded match of American football (Liangyou 101 (1935), 54).