| Author: | Jennifer Way |

| Title: | The House Whitefield Lovell Built: Materializing Ethnicity in Spaces of Art Display |

| Publication info: | Ann Arbor, MI: MPublishing, University of Michigan Library Winter 2002 |

| Rights/Permissions: |

This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information. |

| Source: | The House Whitefield Lovell Built: Materializing Ethnicity in Spaces of Art Display Jennifer Way vol. 3, no. 2, Winter 2002 |

| Article Type: | Essay |

| URL: | http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.pid9999.0003.205 |

The House Whitfield Lovell Built: Materializing Ethnicity in Spaces of Art Display

All images courtesy of the artist and D.C. Moore Gallery. For full citation information click on the thumbnail of each image.

University of North Texas Art Gallery

Since Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House appeared as a book based on an article published in Fortune magazine in 1946, middle-class domestic structures and spaces, and activities occurring in relation to them, have supplied authors and artists with a wealth of themes for creative exploration. [1]In a novel called House (1985) author Tracy Kidder updated the postwar tale of blunders set in motion as Mr. Blandings attempted to maintain control over the complicated process of designing and constructing a home for his family. Chiefly, Kidder shifted the focus from execution gone awry to a nuanced, socio-psychological account of how building a home reveals as well as modifies the identities of individuals involved. A more recent project focused less on personality than it highlighted what we expect to happen, or not, in domestic spaces. This was Home" (1960) with a capital H," a normally functioning house located in Southeast London that exhibited fifty works of art to the public (Millard 58). Another art project dissolved signs of domestic life into a representation publicized intensely by the art world and mass media, followed by its erasure. The original Victorian, terraced building in East London that furnished the starting point for the project was cast in concrete in 1993 by sculptor Rachel Whiteread. The process of casting destroyed the building and a year later, the concrete cast was bulldozed. Today, House exists as a photograph only.

After mid-century, the appearance of homes in and as visual art has served especially as occasion to treat middle-class family life as a melodrama inflected by forces of capitalism, mass culture, gender, and other discourses shaping and shaped by power. Think of the American artist Jim Dine, arms folded tightly over his barrel-shaped chest, staring sternly from and looming tall over the corner of a house" he fashioned in 1960 in lower Manhattan as a temporary installation comprised of thick layers of the detritus of consumer culture (Kaprow #68). Consider the life-size installation called Kitchen, (1995) replete with appliances, furniture, even water in the sink, an apple pie in the oven and debris in a dustpan, the entirety of the surfaces of which artist Liza Lou spent five years beading painstakingly, with the result that every facet of Kitchen glittered spectacularly.

Some of these examples occurred as text, others as three-dimensional installations, and most appeared in places other than a museum or gallery proper. Although all promoted domesticity as a subject of continued interest to the humanities and arts, none interrogated how the theme or kind of domesticity, for instance, specified by class or geographic location, or how textual or visual representations concerned with domesticity might be used to identify and critique techniques the art world tends to employ in presenting its products, including the meaning and significance accorded these techniques. In contrast, Whispers from the Walls, an installation that Manhattan-based artist, Whitfield Lovell, created in the University of North Texas Art Gallery in 1999, reconstituted evidence of everyday life experienced at the economic level of near-subsistence, seemingly without luxuries of time or materials, such as opportunity to obsess over the potential surfaces have to sparkle. [2] Furthermore, the presentation and domestic content of Whispers from the Walls 's representations of southern vernacular life directly illuminated the mythologies that maintain a tradition of repressing cultural difference in spaces of art display.

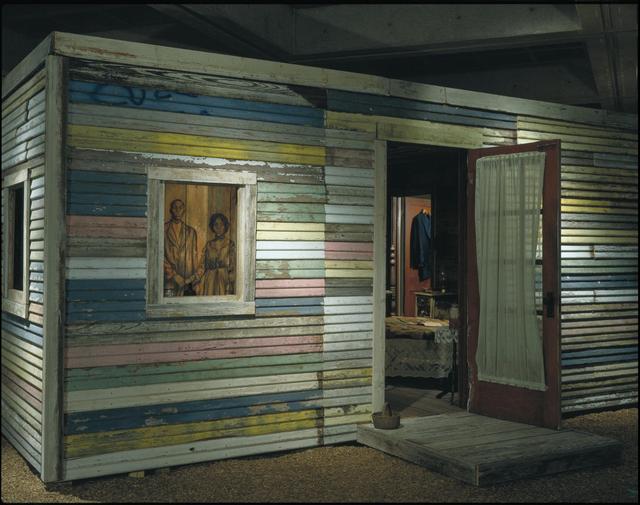

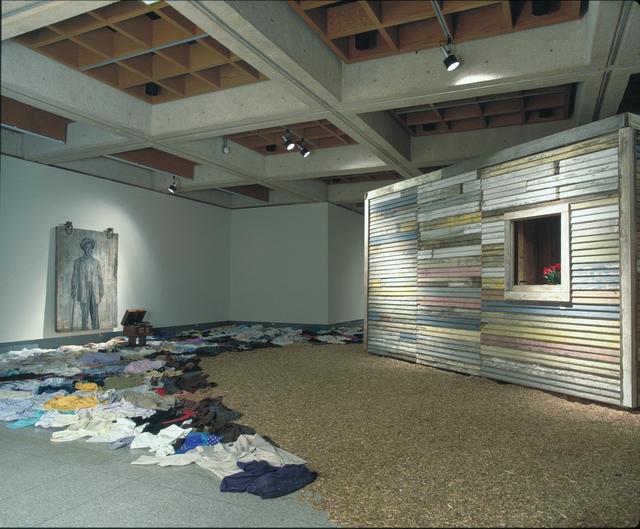

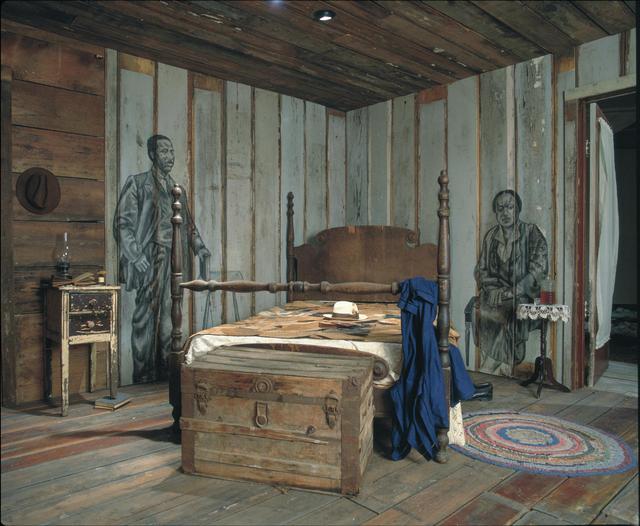

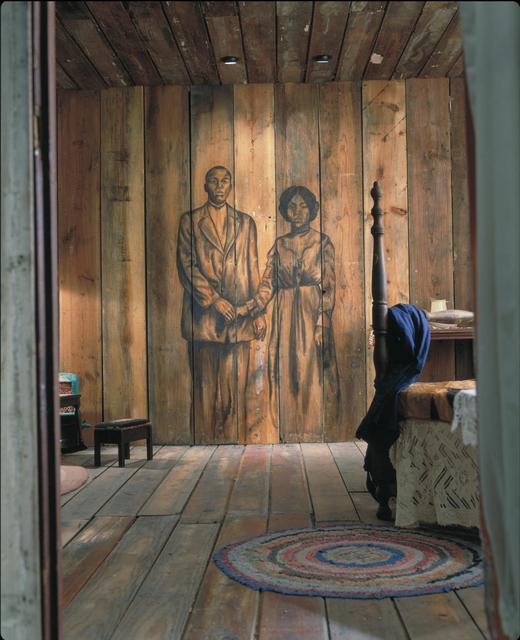

The installation featured a four-wall, one-room house built to scale from fragments of buildings that once framed the everyday lives of African-American individuals in north Texas. Lovell furnished the house he located in the center of the gallery with items representing what a family working crops might have possessed and used daily in the 1920s. Thanks to a concealed audio player, inside the house visitors heard voices speaking softly. Nearby, an old phonograph scratched out Rising River Blues. Conversation and music repeated. From roughly two thousand photographs he examined at the Texas African-American Photography Archive in Dallas, Texas, Lovell selected about one hundred to be photocopied. As he drew well-dressed men and women on the inner walls of the house, Lovell referred to the early twentieth-century, family album-type, black and white images. Life-size figures he rendered in charcoal appeared to stand quietly and stare straight ahead. Lovell positioned the figures so that windows and doorways framed and mirrors reflected them. His sensitivity to material and metaphorical connections born of location and looking cultivated a series of glances exchanged between the figures and visitors, across space and time. Lovell covered the gallery floor with mulch manufactured by the City of Denton. Next to this he spread hundreds of articles of clothing on which visitors stepped as they crossed the front of the gallery to reach, enter, and walk through the house.

We would argue," wrote Isaac Julien and Kobena Mercer in Screen, 1988, that critical theories are just beginning to recognize and reckon with the kinds of complexity inherent in the culturally constructed nature of ethnic identities, and the implication this has for the analysis of representational practices" (3). More than a decade later, how much wiser are we to the ways academia and other institutions concerned with visual culture maintain or disable mythologies that inform their representational practices and thus participate in the construction, analysis, and reproduction of ethnicity and ethnic identities? In examining art history survey texts, for example, Kymberly Pinder remarked, I consider [my] critique to be less about the pedagogical discourse surrounding the survey and more about black representation in our visual culture and the potential of academic debate to mediate it" (533).

Certainly mythologies mediate representations issuing from institutions of higher learning and fine art. In the Fifties, Roland Barthes defined them as narratives through which dominant groups speak what sustains their power, and others hear and accept as common sense, normalcy, and naturalness (112, 129, 143). Could whispers, a mode of speech barely audible, negotiate successfully the status and power long associated with spaces of art display, and so make audible mythologies they maintain and to which they otherwise contribute? For example, how did Whispers from the Walls materialize traditions of and operations by which such mythologies squelch references to ethnicity in gallery and museum spaces?

In what follows, as I address these questions, it may strike some readers as odd that I begin by emphasizing essays by Kenneth Clark and Brian O'Doherty, two individuals whose lives and careers probably intersected rarely, if at all. [3] Nevertheless, and despite that the twenty-two years separating Clark's The Ideal Museum" and O'Doherty's Inside the White Cube, Part 1: Notes on Gallery Space" just about spans a generation (the essays are now forty-seven and twenty-five years old, respectively), the importance of the themes and mode of analysis of each essay extends to the present day. Of even greater significance are the ways we can profit from the dialogue engendered by reading the essays in relation to one another. Therefore, I rehearse Inside the White Cube" as a means to access and, especially, to provide a provocative critique of what The Ideal Museum" presumed about some of the ways that modern gallery and museum spaces produce and maintain power. As a preamble requisite to demonstrating how Whispers from the Walls employed black representation" critically, I reconstitute this theme I perceive to link O'Doherty's essay to Clark's. In the place O'Doherty described pejoratively as a white cube" and chamber of aesthetics," and which Clark more or less celebrated as a work of art, Whispers from the Walls charged southern vernacular life with illuminating a tradition of repressing cultural difference. I especially emphasize the ways in which the presentation and domestic content of Lovell's installation materialized mythologies that tend to divert attention from or eliminate references to ethnicity in spaces of art display.

Dimensions of Mythology in Spaces of Art Display

In The Ideal Museum," Kenneth Clark described the museum as an esteemed cultural space:

Roland Barthes's discussion of mythology can elucidate some of Clark's claims. Barthes tells us that mythology is a system of communication based on signification. It consists of ideas-in-form" that transform history into nature." Indeed, mythology is a loss of the historical quality of things." It abolish[es] the complexity of human acts, giv[ing] them the simplicity of essences." Mythology produces depoliticized speech" (112, 129, 143). Mythology dispenses with historical qualities and reduces complexity to essence as it represents the world as a place without contradictions because it is without depth, a world wide open and wallowing in the evident, it establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves" (143). Mythological dimensions of the museum as described by Clark include that the museum unite[s] so many conflicting claims" —sanctity, classical values, snobbery, pedantry, ethnological curiosity—without addressing any in their individual specificity and relational complexity. Also, as sites of art display, the museum and the gallery assume the identity and status of art, thereby suppressing distinction and staving contradiction between the container and the contained. Brian O'Doherty explained, The sacramental nature of the space becomes clear, and so does one of the great projective laws of modernism: as modernism gets older, context becomes content" (Inside the White Cube" 25). Clark thought the museum and gallery themselves become works of art that are (and can only be?) artificial creations."

In some ways thinking very much like Barthes, O'Doherty claimed that although galleries have power, they subtract the visible proof of and means by which it operates:

One result, O'Doherty insisted, is that what occurs inside galleries enjoys autonomy from daily life. O'Doherty proposed that galleries share this tendency to redirect attention from the everyday. Like the architecture of the church...courtroom [and]... the experimental laboratory," (Inside the White Cube" 24) galleries privilege isolation and specialization, thereby cultivating a repetition of a closed system of values." (Inside the White Cube" 24). The point recalls Barthes understanding mythology as that which organizes the world" and establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves" (143).

Clark and O'Doherty alluded to techniques capable of investing spaces of art display with importance while obscuring social realities that establish and nourish their authority. What traditions of thought and practice inform this kind of power, which encompasses two and three dimensions, in that the interior spaces of galleries and museums function as both space and image? We have now reached a point," O'Doherty surmised, where we see not the art but the space first.... An image comes to mind of a white, ideal space that, more than any single picture, may be the archetypal image of 20th-Century art" (Inside the White Cube" 24). What accounts for an environment having white walls as its predominant feature and enduring as the ideal space for presenting art, so ideal, in fact, that the environment endures in the manner of an archetype to which we become so accustomed, that the environment seems remarkable only when qualified?

In reconstituting meanings that architects and designers associated with white-walled spaces in early twentieth-century Europe and the United States, art historian Mark Wigley concluded:

Typically in an art gallery, broad expanses of unarticulated white or near white surfaces catalyze visitors' experiences of sanctity, formality, and mystique. Wigley expounded:

In spite of its vulnerability, whiteness has long succeeded in imbuing galleries and museums with an aura of power. Visitors who expect, even desire, to confront art disengaged visually and materially from everyday life are rewarded by the efficacy of galleries and museums in offering art in an all white environment, the whiteness of which—like paintings that modernists deemed successful—does not represent, but rather, embodies something. In this case, the whiteness characteristic of gallery and museum walls embodies utopia—no place, yet a perfect place (McEvilley 8). Not surprisingly, spaces of art appearing to elude marks of the quotidian and evidence of process and change prompted Clark and O'Doherty to associate galleries and museums with religious architecture. O'Doherty wrote:

Of course, the outside world is there, inside galleries and museums. However, the interior spaces of galleries and museums transpose traces of daily life into attributes of utopia. This reflex corresponds to the work (the artifying") that spaces of art display perform on art therein. To wit, it is now impossible to paint up an exhibition without surveying the space like a health inspector, taking into account the esthetics of the wall which will inevitably 'artify' the work in a way that frequently diffuses its intentions" (Inside the White Cube" 30). Moreover, the aspect of fantasy and obsession Wigley attributed to white walls, O'Doherty leavened with chic," which flavors the white cube" with taste and the condition of being fashionable (Inside the White Cube" 24). Chic hints of a market-driven economy, wherein difference between products (including works of art), even between older and new versions, masquerades as newness (Farschou 234-56). Interestingly, before O'Doherty perceived that the quality of chic" tethered gallery and museum spaces to a system of values responsive to economic activity, which belies the autonomy these spaces (and their champions) insist distinguishes their concerns and wares from cultures and economies of daily life, Clark's language betrayed how spaces of art display appearing to lack signs of history actually failed to silence echoes of past and contemporary events:

To be sure, O'Doherty, too, proposed that galleries effect transformations. Specifically, art and space change: Gradually, the gallery was infiltrated with consciousness. Its walls became ground, its floor a pedestal, its corners vortices, its ceiling a frozen sky. The white cube became art-in-potency, its enclosed space an alchemical medium" (The Gallery as a Gesture" 87). For Clark, parameters for what whiteness embodies resulted from spaces of art display executing magical alterations that unwittingly hint of political economic systems shaping a world beyond the gallery and museum. This discourse has had a long tradition of treating difference as a distinction that separates and sometimes contrasts white from not white—known also as colored." Clark referred to the discourse as a clearing, in other words, an ordering that comes from curators whose activity in the white cube" manifests parallels with imperialism, especially because one result of curation is the civilization of sounds that gallery visitors would hear otherwise as cacophony animating a jungle." Critic Thomas McEvilley detected in the white walls of gallery and museum space an agency having the capacity to remove color from historical representation: The white cube was a transitional device that attempted to bleach out the past and at the same time control the future by appealing to supposedly transcendental modes of presence and power" (11).

David Batchelor consolidated historical associations linking whiteness, order, imperialism, and erasure under the term chromophobia," by which he meant a fear of contamination and corruption by something that is unknown or appears unknowable." As the other to the higher values of Western culture," color, Batchelor maintained, has long signified a foreign body—usually the feminine, the oriental, the primitive, the infantile, the vulgar, the queer or the pathological." Color is subjected to extreme prejudice in Western culture. For the most part, this prejudice has remained unchecked and passed unnoticed." The result has been a repression of color in the designed and built environment (22-3). Mark Wigley concurs:

Materializing Mythologies

Expectations that white surfaces make the best environment in which to display art is something that many, although certainly not all, professors of studio art maintain today. In critiques, students learn that white walls are necessary for presenting their finished projects. Whiteness embodies lack of color, as in, lack of that which might detract or distract attention from student work. In addition, because whiteness materializes the nothingness requisite to beginning a process of making something from nothing, for class assignments, many professors ask their students to draw, paint, or print on a white page, board, or canvas ground." The point is that in myriad situations at institutions of higher learning, art students come to realize that individuals they perceive as having authority in the (art) academy privilege whiteness as the basis from and on which creativity takes shape and then faces a public. Whiteness activates art ontologically—the conditions of something being art, and demonstrates and reinforces it epistemologically—how to know what is art.

Whitfield Lovell guided students in changing the white walls of the University of North Texas Art Gallery. For one thing, he instructed them to paint the walls gray, the temperature and value of which he considered carefully. During the last week of his residency, tables inside the gallery held sample paint charts that Lovell examined carefully to determine which value of gray might work best. He was treating the whiteness of walls as a feature traditional to twentieth-century galleries that he wished to qualify. In addition, he ordered track lights turned away from the walls to highlight the center of the gallery. Together, Lovell and the students were engaging by nullifying certain material conditions—white walls, lights trained on areas of white walls where art might hang. Countless studio classrooms and student art projects, as well as art world spaces, privilege these conditions in the name of academic and professional practice, tradition, and common sense. Yet, it is possible to understand the art world's privileging of white surface as an example of the art world maintaining a technique of control—a white surface makes distinctions, draws lines, classifies, making certain things stand out as other, rendering them as other, so that they can be patronized or removed" (Wigley 361-2). The technique responds and contributes to shaping cultural and social meanings, and thus it participates in a more widespread effort to manage chromophobia.

To build the house Lovell purchased peeling pink, green, yellow, and gray clapboard walls salvaged from homes in north Texas. Two doors and the framework for two windows came from a house slated for demolition. Lovell said the fragments have a certain kind of beauty" that moved him. Moreover, it was how walls, doors, and window frames signified history in the faded aspect of their multiple colors and in their stains and cracks that appealed to him. Lovell suggested that to get rid of objects exemplifying history of use would be tantamount to losing memories. (Lovell, Lecture to Seminar in Museum Education).

Compare the history Lovell espied in fragments of clapboard walls, to salient features of an art gallery as enumerated by O'Doherty: Unshadowed, white, clean, artificial, the space is devoted to the technology of esthetics. Works of art are mounted, hung, scattered for study. Their ungrubby surfaces are untouched by time and its vicissitudes. Art exists in a kind of eternity of display..." (Inside the White Cube" 25). Along with their colors and signs of wear, the use and memory Lovell associated with the fragments defied the ungrubby surfaces...untouched by time and its vicissitudes" that visitors expected would characterize a space devoted to the presentation of art at the University of North Texas. In fact, Whispers from the Walls provoked awareness that the gallery, house, and also the tableaux Lovell staged around the gallery shared some features while, at the same time, they seemed curious, different, even strange in relation to one another.

Darkened gray walls lacking illumination coaxed visitors to shift attention the art world trains them to direct to the white walls of a gallery to worn, clapboard panels articulating the modest dimensions of a small house. On three gallery walls Lovell installed a tableau consisting of life size images of men and women he drew in charcoal on found fragments of a wall. In front of two Lovell placed old chairs, which he surrounded with clothing he arranged carefully on the floor. Electric lights recessed in the gallery ceiling highlighted each tableau dramatically, and so called attention to other lights of similar brightness in the gallery, chiefly those trained on the house and its contents. The way Lovell deployed lights and sited the house so that its corners pointed to the center of three gallery walls may have prompted visitors to consider what else the tableaux shared with the house, such as physical similarity in the architectural fragments, the drawing style Lovell used to render figures on walls inside the house and for each tableau, and that neither walls of the house nor the fragments of walls comprising the tableaux displayed the expanse of whiteness and negligible texture typical of an art gallery.

Since Lovell worked with materials, objects, and a space existing already, that is, a white cube"—the University of North Texas Art Gallery, his activity invites consideration as consumption, a cultural use that yields, even makes possible, the production of new meaning and significance from the world as we find it. John Storey explains:

Particularly as theorized by Michel de Certeau, the concept of cultural consumption has great potential to open for questioning and ultimately clarifying both Lovell's process as an artist and that to which Whispers from the Walls aspired.

For example, much of what became Whispers from the Walls, Lovell acquired in and around Denton, Texas in the form of consumer goods that had been used up, discarded, then revalorized by vendors at flea markets and antique and second-hand stores as commodities having a status ranging from outright junk to a find." In using what one finds or confronts, de Certeau stated that the individual manifests traditions and expectations thereof: The imposed knowledge and symbolisms becomes manipulated by practitioners who have not produced them." In so proceeding, between the person (who uses [ready-made products]) and these products (indexes of the 'order' which is imposed on him), there is a gap of varying proportions opened by the use that he makes of them" (31-2). Of what did the practice and techniques of using" ready-made materials, objects, and a space consist, and what significance did they hold for Lovell, for visitors, including faculty, staff and students of the academic institution in which Lovell built and displayed his installation, and for art and cultural historians who study and write about Whispers from the Walls, and those who use" their academic accounts? Also, how can the concept of manipulation by practitioners who have not produced them" articulate the use that many visitors to Whispers from the Walls made of some very concrete gaps?

After all, walls of the house did not insist visitors experience only one of their surfaces. Nor did they obscure a sense of the selves and locations of visitors, as Mark Wigley remarked about white walls:

Instead, aged, colorful, and varied in their texture, the fragments of clapboard walls that Lovell chose as his material, he embellished with doors facilitating movement in, through, and around. Thus, walls of the house collaborated with the walls of the gallery in marking boundaries and charging space as passage, as they opened for consideration what histories visitors anticipated walls in a gallery would bear.

The installation achieved a lively hybridity of traditions, genres, forms, voices, and questions consisting of examples from high modernism (white cube"), genres of visual and designed arts (such as drawing, architecture, and photography), new forms of creative expression (installation as an artistic form), the material culture of everyday life (utensils, furniture, and clothing), mass entertainment (a musical recording), resources specific to Denton, Texas (a particular kind of mulch), participation (visitors on and inside the work"), and themes in literature (for instance, from Daughters of the Dust [1999], a novel by Julie Dash that I discuss below), and Cultural Studies (representational practices, consumption as a set of productive acts, ethnicity, and African-American history). We might even conclude that the hybrid dimension of Whispers from the Walls possessed an ethnicity related to the artist, who is African-American; therefore, it could prove key in revealing what the identity of the artist contributed to the significance of his work. As Paul Gilroy proposed, The living, non-traditional tradition of black vernacular self-fashioning, culture-making play and antiphonic communal conversation is complex and complicated by its historic relationship to the convert public worlds of a subaltern modernity" (13).

However, in the future we will need to study more carefully than the purview of this essay permits, exactly how and with what kinds of results theoretical models for making sense of practices involving use and reuse afford opportunity to address gaps between users situated in various and sometimes overlapping locations" of culture, society, and economy, and between histories of kinds of making use (for instance, how canonically sanctioned practices of modernism and postmodernism relate to techniques of self-fashioning and culture-making, such as communal, and subaltern, to which Gilroy referred). In this way, we will be better equipped to elucidate how works of art and visual culture motivate what is ready-made to expose and modify power in spaces of artistic activity, gallery, and home alike.

The significance of domestic walls and spaces

Lovell focused on the 1920s as some African-American individuals lived it in the south. Rarely do histories of art include, let alone analyze, representations relating to their experiences. [4] In fact, what art historians mean when they link African-American individuals and the 1920s points primarily to the Harlem Renaissance, a concept signifying contributions that African-American individuals residing in the Northeast United States made to an early American modernist culture. Furthermore, art historians studying the Harlem Renaissance emphasize northern as opposed to Southern realities, and urban, not rural life. [5]

Of course, the men and women whom Lovell drew on walls in the house he built in the middle of the University of North Texas Art Gallery were no longer alive. He based his drawings loosely on photographs, the material substance of which, although fragile, nevertheless lent the images a longevity and thus a potential for currency that their flesh and blood subjects lacked. Many references to African-American individuals, families, and communities creating and maintaining the combination of a wall and photographs as a vehicle for historical representation can be found in Daughters of the Dust. In this novel, a good part of which takes place in the early twentieth century, Julie Dash tells the story of Amelia Varnes, who is undertaking fieldwork on the Gullah culture of the Sea Islands in order to write her thesis and so complete her graduate degree in anthropology at Brooklyn College (30-2). The process takes Amelia to Dawtuh Island, where houses in which her family had lived for generations nourished the current one with memories of those that had passed. For example, Elizabeth, Amelia's cousin, was living in a house belonging formerly to Nana Peazant, and she coached Amelia in appreciating what made a particular wall so very important: its colorful collage of newsprint, packaging, letters, and photographs documented the history of their family and community (82-3, 86).

Whispers from the Walls offered more than a series of physical supports for displaying photographs that chronicle generations gone long ago and more recently, in that Lovell consulted old photographs of African-American men and women as a resource for his imagery. In addition, the manner in which he drew on and into the walls of the house integrated photographic-based images of African-American men and women into the very structure of domestic space. Using crumbling bits of charcoal, Lovell delicately traced figures and, wielding thicker sticks of compressed charcoal, darkened shadows and delineated costume. With chamois cloth he rubbed and blurred lines. Lovell applied charcoal on and inserted it into wooden planks, thus charging components of architectural structure with giving body" to photographic representations. [6]Upon completion, soft golden areas of the wooden planks simulated areas of light value in the black and white photographs. Together with darker passages Lovell rendered by applying charcoal heavily, the light areas helped to model the figures and create the illusion of people having three, even four dimensions, if we consider time—of the artist producing and history lived—as a dimension. Something else enlivened the drawings. Lovell implied connections between them and items he arranged in the house. A comb and brush set, a hat, a pair of shoes, a cup and saucer—Lovell placed these next to charcoal images of men and women. Behind a real table holding an open book, light, and hat, a man drawn on the wall seemed to gesture slightly as if reaching for the book.

Changes that use and time wrought in the wooden artifacts with which he constructed the house and tableaux compelled Lovell to reflect on his own memories. In this sense, he situated his work in a familial topography. To students at the University of North Texas, Lovell spoke of his fascination with stories that elder members of his family told him about their lives in South Carolina (Lovell, Lecture to Seminar in Museum Education). As a child Lovell spent time in the town of Blair in Fairfield County, located in north central South Carolina and in 1996, while on a road trip he made from Houston to New York, [7] Lovell visited members of his family still living in and around Blair, where he remembered shack-type homes and women working with garden utensils who wore large, vibrantly colored hats. However, in returning to Blair as an adult, Lovell noted many changes. Nice brick homes had replaced the shacks and to Lovell, this sounded the death of a culture. He became an inveterate collector of family photographs and recorded one of his grandmothers telling stories about them (Lovell, Lecture to Seminar in Museum Education). Lovell recalls a point during the mid-1980s when elderly members of his family began to pass away—We were losing people" (Lovell, Lecture at Student Union).

Lovell's proactive response to the vulnerability of his family's history to disappearance calls to mind In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens," the essay in which Alice Walker figured creativity as women whose lives remain unacknowledged and therefore unstudied by institutions of high culture, despite the daily ways in which the women had managed to bring together a few moments, a bit of energy, and very modest material resources from which they wrought magnificent results (238): I notice that it is only when my mother is working in her flowers that she is radiant, almost to the point of being invisible—except as Creator: hand and eye. She is involved in work her soul must have. Ordering the universe in the image of her personal conception of Beauty" (241). Interestingly, in moments of engaging with their gardens," creators do disappear—almost to the point of being invisible." At the same time, they become omnipresent. Like photographs documenting a past that Whispers from the Walls elicited and animated, artifacts and families witnessed and remained after the women whom Walker memorialized had completed their activities and eventually, their lives.

bell hooks would have likely espied a political dimension in Lovell's sensitivity to space inside the house and out. In the essay Black Vernacular" hooks writes:

In 1992 artist Rick Lowe established the not for profit organization called Project Row Houses in what he first encountered as an abandoned lot of shotgun houses built in Houston, Texas during the 1930s. [8] Scholars trace the origins of the shotgun house, consisting of a building several rooms deep but having the narrow width of only one room, to free Haitians who settled in New Orleans in the early nineteenth century, and to one-room dwellings traditional to the Yoruba in West Africa, from where Africans left to arrive in the United States as slaves. Sheryl Tucker read in the placement of shotgun houses a narrative of individual and community:

The house Lovell built had a depth of only one, not several rooms, so it did not exemplify exactly the definition of a shotgun house. Nevertheless, its width and colorful appearance resembled the shotgun house formally, thereby invoking its tradition of sheltering people who experienced dramatic change in their social status and with great resolve, forged new ways of life and community.

Undoubtedly, Lovell worked on Whispers from the Walls with awareness that a racially segregated society of the early twentieth century manufactured what a family living in the kind of house he built, owned. bell hooks reminds us that in their circumstances, photographs of family did more than visually represent history, as Dash commemorated in her novel. They nourished and toughened walls of the home with resilience. hooks notes:

Walls of the home supplied prompts for recollection, in other words, historical thinking and feeling—using these images, we connect ourselves to a recuperative, redemptive memory." They imparted clues that would sustain future activities—The walls of pictures were indeed maps guiding us through diverse journeys" (In Our Glory" 52-3). [9] In addition, they supported a form of creativity that was life affirming; images and words celebrated achievements unacknowledged in the spaces and texts of mainstream visual and literary culture. By enriching time present with intimations of the past and affirmations to realize in the future, the interiors of these homes frustrated an operation endemic to spaces of art display—the reduction of art to a place and moment disengaged from time experienced in all its complexity and inclusiveness (McEvilley 7).

Stories we make

Does the critique I argue Whispers from the Walls enacted become visible only when a gallery provides its frame? Might it take strength from other walls intended to perform as questioner, such as the Wall or Respect," a mural painted on a tavern in Chicago in 1967 by the Visual Art Workshop of the organization of Black American Culture (Donaldson 22-6)? Does an awareness of how power can shape and inhabit space tell us anything about homes resembling the house Lovell built, homes that today comprise entire neighborhoods throughout the South? Or, homes and yards in which some African-American artists produce on a long-term basis, and in which members of the art world are becoming interested? (McEvilley, The Missing Tradition" 82-3). It is important to question the nature and reach of the critical aspect of Whispers from the Walls. In response, I would like to conclude by considering the participation of the installation's visitors in exploring the culturally constructed nature of identities" (Julien and Mercer 3).

In describing spaces designated for art, Kenneth Clark linked institutions, power and language. As works of art themselves, such spaces should command the same faculties which are involved in the writing of an opera..." (83). In contrast, Whispers from the Walls mobilized languages of everyday speech, acts of looking, and accounts of personal and community experiences. The title of the installation suggested that walls say something. In fact, visitors to the installation heard soft-spoken conversation resonate through the house. Although visitors strained to catch them, words enunciated were barely comprehensible and always in the process of being lost. Outside the house, a Detrola phonograph Lovell placed on the floor turned a record round, materializing a person not present in body but voice. [10] Visitors standing on a shallow porch extending from the front door of the house looked inside, where they saw images of a man and woman on the wall opposite the door. Visitors exchanging glances with the images collapsed time past into the present, conflated photographic documentation with presence, in that Lovell based his drawing of the couple on photographs, and merged the two dimensions of a wall (and photograph) into space vitalized through sensory, visceral experience.

Lovell blended charcoal to merge with dark vertical grains and cracks of wood, tracing the contours of the figures down to the point where the wall met the floor. Curiously, the figures' lower legs and feet were not visible. The effect was that this part of their bodies descended into what visitors may have surmised were the foundations of the house. Is immobility what Lovell wished to convey—that something rooted individuals to this spot and precluded their leaving? Was Lovell alluding to their potential for movement in the house? In the latter scenario, the floor substituted (was a metonymy) for the figures' lower legs and feet. Both interpretations follow from Lovell joining image and surface (the wall), image and structure (wooden planks), and individuals to place. In addition, the house made possible another kind of joinery."

Glimpsed through its doors and windows, or from inside the colorful framework shaping the house, reflections in mirrors suggested the physical proximity of visitors to the men and women Lovell drew on the walls. For example, as they looked into a large mirror balanced atop a bureau, visitors saw themselves adjacent to individuals with whom they would have had little chance to interface otherwise, since the photographs Lovell used as a resource for his drawings represented people long dead. Aptly, then, the reflections could stimulate visitors to think about what kinds of nearness and belonging visual representations are capable of generating, and what it means to view oneself next to a face (and inside a space) that history and art history ignore. In many ways, Whispers from the Walls catalyzed the coming together of lives and experiences, the likelihood of which Barthes claimed mythology reduced.

Lovell worked similarly with clothing. Strewn with shirts, skirts, dresses, pants, nightclothes, and other garments, the perimeter of the University of North Texas Art Gallery resembled a colorful, flat pedestal marking the intersection of the plain gallery floor with the house and mulch. For visitors, differences in height (the house stood a few feet above the floor) and materials (wooden house versus fabric clothing) may have called to mind models for interpreting works of art consisting of center (house, home, family) versus periphery (yard, land, environment, nature). However, in that the clothing integrated instead of separating priorities, practices, and parts, it united, even confused the distinction between center and periphery. Furthermore, it magnified the scope of the installation's significance.

Clothing represented a sizeable population, members of which wore and may have made it. Clothing signified the activity of labor progressing through fields of cotton grown as an agricultural crop, factories transforming cotton into cloth, factories producing clothing, sites associated with the circulation of consumer goods, including the display and distribution of clothing, and places of storage and use involving owning, wearing, and discarding clothing. Among the items Lovell installed in the house were articles of clothing. People he drew on walls inside the house and on tableaux installed in the gallery had dressed up.

Where, according to O'Doherty, conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values" (Inside the White Cube" 24), Lovell buil[t], by virtue of constructing locations...a founding and joining of spaces," a producing, in terms of letting appear" (Heidegger 332). Clothing connected house and gallery while broadening its signification to encompass crop, population, and labor. Clothing worn by individuals that Lovell drew in the house and as part of tableaux invoked practices whereby visual culture and identities coincided, such as wearing one's best in a photographic studio. [11] The men sported suits and hats, and the women wore puffy, long sleeved, high collar blouses and long skirts. Their clothing related them to an American society valuing position through appearance, including the appearance of propriety. It performed architecturally by constructing bodies that housed psyches for entrance into and acceptance by a community.

Without question, Whispers from the Walls invited visitors to invest clothing with additional importance. Lovell anticipated that as they walked on and felt pants, shirts, dresses, and slips brush against their feet, visitors would rearrange the garments and thus reconfigure the appearance of the installation. Of course, visitors achieved as much when they added their reflection to those of men and women drawn on the walls. Opportunities to participate directly in, especially by altering what counted as the work of art, spoke loudly, clearly. Rather than capitulate to mythologies that organize the world" so that things appear to mean something by themselves" (Barthes 143), visitors helped to transpose a white cube" bereft of history, to a place rich with connotations of the past and evidence of activity ongoing in the present.

Unexpected visual juxtapositions of selves" living now with subjects long gone but coaxed into presence as whispers," in combination with physical contact with old clothing, solicited inquiry into the significance of being immersed in the material thickness of the past. The situation promised to shift visitors' perceptions of who comprises the past from them" to us," and provoke questions about our" vulnerability to values and choices that determine which lives and experiences history will memorialize. In addition, visitors may have been moved to take stock of their own power to establish relationships to lives long gone. Surely, this expansive line of thought challenged the status of the art gallery as a repetition of a closed system of values" predicated on isolation and specialization (Inside the White Cube" 24), especially because it interrogated, simultaneously, traditions of institutions and discourses, practices of representation, and experiences constitutive of subjectivity. Whispers from the Walls welcomed visitors to charge a host of old things having little importance for academia and institutions of the art world, as an environment fostering occasion to reconsider what stories we tell about who we are to reflect what we have learned about where we have been" (Fishkin 456), and wonder, too, at the ways spaces of art display can foster or frustrate the telling of our lives.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: The Noonday Press, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Batchelor, David. Chromophobia. London: Reaktion Books, 2000.

Clark, Kenneth. The Ideal Museum." Art News 52. 9 (January 1954): 20-31, 83-4.

Daniel, Pete. Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life since 1900. New York: Hill and Wang, 1986.

Dash, Julie. Daughters of the Dust. New York: Plume, 1999.

Daughters of the Dust. Dir. Julie Dash. Perf. Cora Lee Day, Alva Rogers, Turla Hoosier, Adisa Anderson, Kaycee Moore, Bahni Turpin. 1991

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1988.

Donaldson, Jeff. The Rise, Fall and Legacy of the Wall of Respect Movement." The International Review of African American Art 15 (1998): 22-6.

Dumenil, Lynn. Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Farschou, Gail. Obsolescence and Desire: Fashion and the Commodity Form." Postmodernism—Philosophy and The Arts. Ed. Kenneth Silverman. London: Routledge, 1990. 234-56.

Fishkin, Shelley Fisher. Interrogating 'Whiteness,' Complicating 'Blackness': Remapping American Culture." American Quarterly 47. 3 (March 1995): 428-66.

Gilroy, Paul. '...to be real' The Dissident Forms of Black Expressive Culture." Let's Get it On, The Politics of Black Performance. Ed. Catherine Ugwu. London: Institute of Contemporary Art, and Seattle: Bay Press, 1995. 12-32.

Heidegger, Martin. Building Dwelling Thinking." Martin Heidegger: Writings from Being and Time to The Task of Thinking. Ed. David Farrell Krell. New York: Harper and Row, 1977. 323-39.

Hodgins, Eric. Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946.

hooks, bell. Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice." Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press, 1995. 145-51.

——-. In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life." Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography. Ed. Deborah Willis. New York: The New Press, 1994. 43-53.

Julien, Isaac and Kobena Mercer. Introduction: De Margin and De Centre." Screen 29.4 (Fall 1988): 2-10.

Kaprow, Allan. Assemblage, Environments, and Happenings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1966.

Kidder, Tracy. House. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985.

Landsmark, Theodore. Comments on African American Contributions to American Material Life." Winterthur Portfolio 33.4 (Winter 1998): 261-82.

Lemke, Sieglinde. Primitivist Modernism: Black Culture and the Origins of Transatlantic Modernism. New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

Lovell, Whitfield. Lecture to Seminar in Museum Education. University of North Texas Art Gallery, School of Visual Arts, University of North Texas. 24 February 1999.

Lovell, Whitfield. Lecture. Student Union, University of North Texas. 3 March 1999.

McEvilley, Thomas. Introduction." Inside the White Cube, The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1999.

——. The Missing Tradition." Art in America 85 (May 1997): 78-85, 137.

Millard, Rosie. Home is where the Art Is." Arts Review [London] 51 (February 1999): 58.

O'Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube, Part I: Notes on the Gallery Space." Artforum 14 (March 1976): 24-30.

——-. The Gallery as a Gesture." Inside the White Cube, The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1999. 87-107.

Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography, Ed. Deborah Willis. New York: The New Press, 1994. 34-40.

Pinder, Kymberly. Book Reviews: Black Representation and Western Survey Textbooks." The Art Bulletin 81.3 (September 1999): 533-8.

Sekula, Allan. Reading an Archive." Blasted Allegories: An Anthology of Writings by Contemporary Artists. Ed. Brian Wallis. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art and Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987. 114-27.

Storey, John. Cultural Consumption and Everyday Life. New York: Oxford UP, 1999.

Walker, Alice. In Search of our Mothers' Gardens." In Search of our Mothers' Gardens, Womanist Prose. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983. 231-43.

Way, Jennifer. Redeeming Art World Mythologies: Working (Ex)change, or, The House Whitfield Lovell Built." The Art of Whitfield Lovell: Whispers from the Walls. Ed. Diana Block. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press, 1999. 29-41.

Wigley, Mark. White Walls, Designer Dresses, The Fashioning of Modern Architecture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995.

1. Hodgins first published his story about Mr. Blandings in Fortune 33 (April 1946). The movie version of the book, directed by H.C. Potter and starring Cary Grant and Myrna Loy, appeared in American theaters in 1948. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers who offered important questions and comments about this paper, which revises arguments that I made first in 1999, and for opportunities to present revisions in progress at the American Studies Association Conference in Detroit, 2000, and the Midwest Art History Conference in Minneapolis, 2001. I thank the School of Visual Arts at the University of North Texas for awarding me funds to attend these conferences. Also, I wish to acknowledge Diana Block, Director of the University of North Texas Art Gallery, who asked me to document Lovell's activity in Denton, as well as Whitfield Lovell, for his kindnesses and provocative, important work.

2. As a Visiting Artist at the School of Visual Arts, University of North Texas, February 3 to March 10, 1999, Whitfield Lovell worked with undergraduate and graduate studio and art education students to conceptualize, plan, and construct the installation he named Whispers from the Walls. For the most part, this activity took place inside the University of North Texas Art Gallery, which is a nondescript gallery space located on the first floor of the Art Building. The University of North Texas Art Gallery stages original and also hosts traveling exhibitions of art and visual culture. Its modest permanent collection is dispersed across faculty offices and other, chiefly administrative spaces on the main campus of University of North Texas, located in Denton, Texas, about forty minutes northwest of the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, respectively.

3. Kenneth Clark was born in Glasgow in 1903. After studying at Oxford, he worked as a Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, then as Director of the National Gallery and Surveyor of the King's Pictures. Clark chaired the War Artists' Advisory Committee. After the war, he served as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University (1947-1950) and Chairman of the Arts Council. In 1954, Clark agreed to be Chairman of the Independent Television Association. His series Civilisation first aired in 1969. He died in 1983. Brian O'Doherty was born in Ireland in 1928; he immigrated to the United States in 1957. O'Doherty has worked as a painter (under the name Patrick Ireland), performance artist, photographer, and writer, including editor of Art in America, 1971-1973.

4. Only recently have scholars begun to study "the uses and aesthetics of [African American] vernacular folk arts and crafts as historical artifacts that can elaborate on written narratives of culture" (Landsmark 262).

5. Not until World War II did the urban population of the South reach even forty percent. Until then, only about eighteen percent of people lived in urban areas (Daniel 4; see also Dumenil 161ff and 284ff). During the 1920s, discourses of primitivism generated many links between members of the art world, "African American culture," and modernism (see Lemke).

6. Lovell exchanged "noise" characteristic of surfaces of old photographs, and by "noise" I mean information extraneous to images per se, such as scratches and marks signifying the age of photographs as material objects, for the noise of wooden planks. In the latter case, noise consisted of marks of wear and age - knots, holes, cracks—characteristic of wooden planks but incidental to their structural function in the house in Whispers from the Walls.

7. During the summer of 1996, Lovell and Annette Lawrence, a member of the studio faculty at the School of Visual Arts, University of North Texas, drove from Houston, Texas, where both had participated in Project Row Houses, to New York City. Along the way they stopped at the homes of their respective families in the Carolinas.

8. In the fall of 1995, Lovell produced an installation in 2517 of Project Row Houses, located at 2500 Holman, in the Third Ward of Houston, Texas. It consisted of furniture and life size drawings of African American individuals on the walls. In fact, its subject matter, materials, and techniques anticipated Whispers from the Walls. Rick Lowe established Project Row Houses as an enterprise for commissioning artists to work in ways that speak to the history and cultural issues relevant to the African-American community, in part of an historic one and a half block site of abandoned shotgun-style houses—ten are dedicated to art, photography, and literary projects. Located in seven houses adjacent to those dedicated to art, The Young Mothers Residential Program provides transitional housing and services for young mothers and their children. In 1997, Deborah Grotfeldt formed Project Row Houses Foundation (PRHF), a non-profit organization that provides technical and financial assistance to artists and organizations involved in cultural and community development projects.

9. How does photographer and critic Allan Sekula's concept of fleeing compare with hooks's celebration of what photographs accomplished in the early twentieth century? Sekula proposed, "In retrieving a loose succession of fragmentary glimpses of the past, the spectator is fleeing into a condition of imaginary temporal and geographical mobility" (122).

10. Detrola was the largest Michigan radio manufacturer operating from 1931 until 1948. At first, in order to create the sound of voices conversing in the house, Lovell recorded himself speaking. However, the results dissatisfied him, so he asked Alva Rogers to help out. She made several tapes that, when spliced together, gave the impression of barely audible conversations taking place somewhere in the house. We may best know Rogers for her performance as Eula in Daughters of the Dust, written and directed by Julie Dash, was released to movie theaters as a full-length feature in 1992.

11. Edward Jones explores the significance of dressing up for one's photograph in "A Sunday Portrait."