Prevention of Conflict in Divorcing Families: SMILE

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Continuing parental conflict and troubled parent-child relationships following divorce predict poor self-esteem in children and parents, inconsistent and ineffective discipline, and involvement of children and adolescents in alcohol and substance abuse, anti-social activity, rebellion, and run-away behavior. This article presents the evaluation results of a court-mandated, community-based conflict prevention program for families experiencing divorce. Recommendations for future program development are discussed.

Key Words: conflict, divorce, parenting, prevention, program evaluation

Anne K. Soderman, Ph.D., is Professor, Department of Family and Child Ecology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 48824.

Mona J. Ellard, M.A., is Home Economist, Michigan State University, Extension Service, Eaton County, Michigan, 48824.

Thomas S. Eveland, J.D., is Judge, 56th Judicial Circuit Court, Eaton County Courthouse, Charlotte, Michigan, 48813.

Though marital transitions continue to be a prominent family feature in the United States, there is little evidence that separating and divorcing partners are making these transitions with any greater ease. For most couples, the process continues to be an intensely negative one. For the more than one million children each year who are involved, there is documented evidence that they can be at risk (Kalter, 1987; Spigelman & Spigelman, 1991; Aro & Palosaari, 1992). On top of normal developmental tasks, these children face an additional set of tasks specific to the divorce experience. At a time when they are in greatest need of supportive parenting, their parents are often less emotionally available to them, less consistent in their parenting approach, and frequently involved in excessive bitterness with one another for at least a two-year period of time. According to studies examining both short-term and long-term effects (Wallerstein & Kelly, 1980; Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1990; Wallerstein, 1991; Zill, Morrison, & Coiro, 1993), the emotional scars of divorce can have pervasive and long-lasting consequences.

More precisely, it is the disruption in parenting that hurts children far more than the divorce itself (Hetherington, Stanley-Hagan, & Anderson, 1989; Camara & Resnick, 1989). Continuing parental conflict following divorce and resulting troubled parent-child relationships is predictive of poorer self esteem in both children and parents, inconsistent and ineffective discipline, and greater involvement of children in alcohol, substance abuse, and anti-social activity (Gullotta, 1981; Kalter, 1990; McKane, 1991).

In adolescence, there is greater rebellion, run-away behavior, and tendency to develop psychosomatic symptoms. These effects seem more pronounced for boys than for girls, with boys exhibiting more externalizing behaviors, such as conduct—disordered and aggressive behavior, and girls showing more internalizing problems, such as depression and anxious behavior (Furstenberg & Allison, 1989; Robin, 1988; Shaw, 1991; Spigelman & Spigelman, 1991). Boys appear to be more exposed to parental conflict—both before and after divorce—and are confronted with more inconsistency, negative sanctions, and opposition from parents—particularly from their mothers, who are nine times more likely to be the custodial parent. Generally, emotional adjustment of children following divorce can be predicted more strongly by postseparation family relationships, while behavior problems are more strongly related to preseparation factors.

In the larger context, some of the toughest social issues we face today are seeded significantly by these factors. For example, when children experience sleepless nights and anxiety or exhibit aggressive behavior and an inability to concentrate during school, it is predictable that they may come to constitute a good share of the school drop-out rate currently plaguing the nation. Moreover, the growing number of women and children constituting the "new poor" is fueled by the economic instability and hostility that often follow many divorces. Ninety percent of parents ordered to pay child support are fathers, and 30% still fail to pay. Of the rest who do, fewer than one half end up paying what was ordered (Meyer & Bartfield, 1996). Shaw (1991) suggested that, since women are more likely to be responsible for the primary care of children, the real income of couples who divorced tends to decrease 19.2% for men and 29.3% for women. Primary custody of children tends to be the single factor most responsible for this difference, resulting in mother-only families with children—currently the most impoverished demographic group in the U. S. (Meyer, Bartfield, Garfunkel, & Brown, 1996).

These financially-based changes impact on children's coping resources in a number of ways, including moving from the family home, changing schools, losing contact with friends, spending more time in child-care settings while mothers are working, and dealing with the custodial parent's concern over financial pressures (Emery, 1988). MacKinnon, Stoneman, and Brody (1982) have suggested that there is a psychological impact as well, in that divorced working mothers provide less cognitive and social stimulation for their children than do married non-working or married working mothers (Shaw, 1991). It seems reasonable, also, that some of these parents who are trying to adjust to a highly stressful event in their own lives are contributing to the growing incidence of child abuse.

Elkin (1985) has suggested that changes must occur in the community in order to facilitate divorce reform and humanize the divorce experience. These include developing and expanding family transition programming for adults to encourage more positive spousal adaptation and family adjustment, as well as structuring programs to help adults better understand the potential negative impact of divorce on children. School counselors and mental health professionals in communities are being encouraged to work together to develop on-school-site peer-support groups for children (Farmer, 1993). Hall, Beougher, and Wasinger (1991) maintain that informing divorcing spouses about the potential negative impacts of divorce on children can be helpful in preventing skewed family relationships and in promoting more effective post-divorce parenting. This article reports on the identification, development, and evaluation of just such a program geared toward strengthening divorcing parents' abilities to deal effectively with one another on co-parenting issues. It also focuses on the perceptions of program participants about the divorce experience and its effects on their children.

Identifying an Effective Educational Program

In response to the need to provide divorcing parents with an educational program, a collaborative effort was initiated between Michigan State University's Extension Service, judges of the 56th Judicial Circuit Court of Michigan in Eaton County, and the Eaton County Friend of the Court to identify an effective program to support transitioning parents with dependent children.

SMILE (Start Making It Liveable for Everyone), a program that was developed in 1990 by Michigan's 6th Judicial Circuit Court Judge Edward Sosnick and family law attorney Richard Victor, was chosen and adapted for Eaton County. The goals of SMILE are:

- to provide information to help parents better understand the effects of divorce on children;

- to help parents understand the needs of their children during and after the divorce process;

- to teach parents how to ease the anger and suffering of their children;

- to promote parents' ability to work with one another more effectively on parenting issues following the divorce and not to use their children to hurt one another.

Community-based psychologists were contacted to volunteer their expertise to the project and to participate in the bi-monthly programs. Educational materials were prepared through the Michigan State University Extension Service for participants attending SMILE sessions, as well as an eight-issue newsletter series focusing on a variety of issues related to the divorce process. These were mailed to program participants as a follow-up strategy to maintain ongoing support and contact. A local church provided space for the programming, and notice of the upcoming programs was shared with the media. Potential participants were notified with personal letters sent from the court requesting that they attend the two-hour session prior to being granted their divorce request.

Evaluation of the Program

While many intervention efforts, such as the SMILE program, have proven to be beneficial, most lack empirical documentation of their efficacy (Grych & Fincham, 1992). This research constituted an exploratory effort to study the effectiveness of the SMILE program relative to participants' post-program stress levels, knowledge of potential effects of divorce on children, personal coping, satisfaction with and use of potentially supportive resources, and their children's reactions to divorce.

THE SAMPLE

All parents (n = 398) who had been court-mandated to participate in the SMILE program in Eaton County during a one-year period were identified by the court and SMILE attendance records. A questionnaire, The Family Transitions Survey, along with a letter from the court asking parents to participate in the survey, were mailed to each participant.

Respondents were primarily white (95%), with 24% in their twenties, 52% in their thirties, 22% in their forties, and 2% in their fifties. Seventeen percent were experiencing divorce for a second or third time. The greatest number (68%) had high school degrees; another 14% had earned an associate's degree; 12% had bachelor's degrees; and 4% had a master's degree. On average, the respondents had 1.6 children, with 49% having children 4 years or younger, 65% with children 5 to 12 years of age, 39% with adolescents 13 to 17 years of age, and 18% with children 18 or older. Most custodial parents lived in the same town as their ex-spouses (62%), with the remainder living in the same state. Seventy-five percent of parents reported full-time employment (29% salaried); of those employed part-time, 93% were females. The majority of respondents (70%) earned $30,000 or less. Of those earning less than $15,000 per year, 79% were mothers. While mothers in the sample earned, on average, significantly less income than that reported by fathers, 70% of mothers reported exclusive physical and/or legal custody of their children. A third of the sample reported sharing joint legal and physical custody, with the remainder having other arrangements. Thirty-one percent of respondents indicated that their own parents or their spouse's parents had been divorced.

A control sample of parents (n = 291) divorcing during this same period but not participating in such a program was identified by the Clinton County Circuit Court and asked to complete the same questionnaire. Seventy-six respondents completed and returned questionnaires. Clinton County respondents were not significantly different from Eaton County respondents with respect to race, age, education, residence, employment, number and ages of children, custody, or income.

MEASURES

Five sets of study variables were included in the evaluation: Personal Stress, Parents' Perceptions of Divorce Effects on Children, Personal Coping, Support Systems/Resources, and Children's Reaction to Divorce.

To measure personal stress, respondents were asked to respond to a checklist of 29 items and to assess the extent to which each had contributed to their stress during the last two years on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Intensely Stressful to 4 = Not At All Stressful).

To tap respondents' perceptions of the effects of divorce on their children, they were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with 12 statements. Seven of the statements loaded on two different factors. The first, children's relationship with non-custodial parent, consisted of four items: (a) it is important for children to spend time with the non-custodial parent; (b) children need frequent and regular contact with both parents; (c) I want my children to think positively about their non-custodial parent; and (d) children benefit by continued contact with friends and relatives of both parents. The second factor, children's adaptation to divorce, consisted of three items: (a) things are getting worse, rather than better, for my children and me; (b) my children are doing pretty well; and (c) the hurt this divorce has caused my children is irreparable; they will probably never fully recover.

Thirteen items on a four-point scale (1 = Agree Strongly to 4 = Disagree) assessed respondents' personal coping. Four of these loaded on one factor, coping. Included were: (a) finding and working with a professional mediator prior to divorce is important; (b) getting personal/family counseling during the divorce process is helpful; (c) finding a support group following divorce can be helpful; and (d) finding continuing counseling after the divorce process is important.

Participants were asked to rate support systems and resources (including friends/neighbors, co-workers, clergy/church, SMILES program, adult support group, counselors, school system, parents or immediate family members, and SMILE newsletters) from 1 (Extremely Supportive and/or Helpful) to 4 (Not at All Supportive and/or Helpful).

To measure children's reactions to divorce, 27 items frequently cited in the literature as common reactions children have to divorce situations were included in a checklist. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they had observed these behaviors in their children on a Likert scale from 1 (frequently observed) to 4 (never observed). Three factors emerged: acting out, emotional neediness, and psychological adjustment.

Once survey questionnaires had been returned, telephone interviews were conducted with a subset of 20 respondents who were selected randomly from the 60% who indicated a willingness to participate in a personal interview. The interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were asked three open-ended questions: (a) What was the most difficult aspect of this transition, for you, for your children, for your spouse? (b) What or who offered the most support during this period, for you, for your children, for your spouse? (c) How hopeful are you about the ability of your family to stabilize in a healthy way?

RESULTS

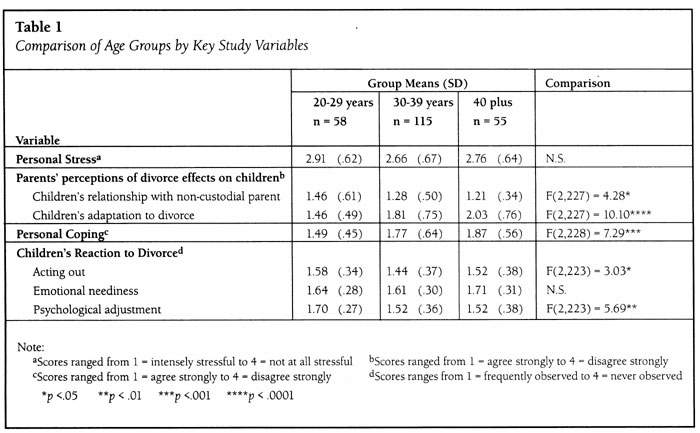

Sociodemographics. Preliminary analyses of relationships between particular demographics and key study variables failed to reveal any significance of racial/ethnic group, education, employment status, or income. Age of the respondents, however, did prove to be significantly related to several of the primary variables (see Table 1). While personal stress was not experienced differently by the various age groups, other variables were meaningful.

When measuring parents' knowledge of the importance of a child's positive relationship with the non-custodial parent, older parents (40 and older) were more likely to agree with the statements (p < .05) than the younger parents. An even stronger relationship was found in parents' perceptions of their children's ability to adapt to the family transition, with older parents the most pessimistic and younger parents most optimistic (p < .0001). Younger respondents were most likely to think that coping mechanisms such as seeking family counseling were helpful; older respondents were least likely to agree about the helpfulness of family therapy (p < .001). In reporting their children's reactions to parental divorce, parents in the group aged 30 to 39 years reported that their children were most likely to act out (p < .05). The three groups were not markedly different in citing emotional neediness in their children, but parents 30 years and older were significantly more likely than those from 20 to 29 to note problems in their children's psychological adjustment (p < .01). Gender differences, which were apparent in the two-way ANOVA used to examine group differences, can be seen in Table 2.

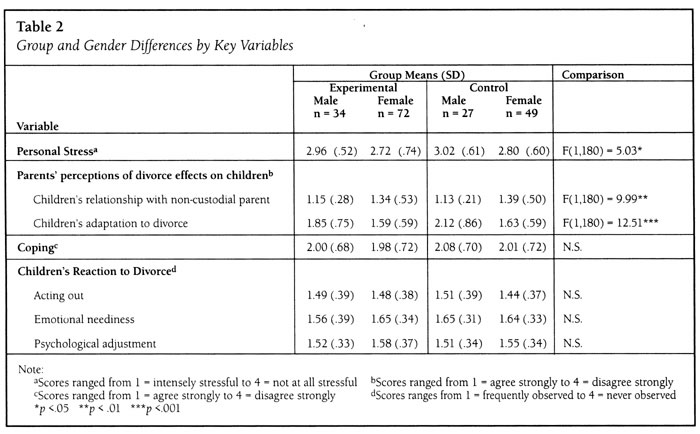

Personal stress. Analysis of the effects of gender on the factor, personal stress, revealed that females reported higher stress levels than males (p < .05) with respect to personal time available to them, household and employment responsibilities, relationships with the extended family, time with their children, and personal finances and budgeting. One of the additional items retained for separate analysis, dealing with the court system, did not prove to be statistically significant, although experimental-group participants were less likely than control-group respondents to rate the experience as stressful.

Parents' perceptions of divorce effects on children. Male respondents were significantly more likely than females to agree with the need to have children spend time with the non-custodial parent, to have frequent and regular contact with both parents, to have children think positively about their non-custodial parent, and to benefit through continued contact with friends and relatives of both parents (p < .01).

With respect to their perceptions about how well their children were doing in adapting to the divorce, men were far more optimistic about the situation (p < .001). Wives were more inclined to say that things were getting worse, rather than better, for their children and them; they disagreed more often that their children were doing well, and they were more likely than their ex-husbands to say that the hurt the divorce had caused the children was irreparable.

Personal coping. There were no notable group or gender differences with respect to personal coping. On two items that were retained separately for analysis (I feel overwhelmed and unable to cope most of the time and I find it impossible to communicate with my ex-spouse), there were group differences. SMILE participants were significantly more likely to indicate that they could communicate positively with an ex-spouse (p < .05).

Support systems/resources. Chi-square analysis of group responses did not indicate differences between the experimental and control groups on use of or satisfaction with potential resources. When respondents considered the listing of 14 separate items that might have provided a measure of support during the divorce process, they indicated that friends and neighbors were most supportive, followed by their parents or immediate family members and co-workers. Identified as least supportive were parents of their ex-spouses, their ex-spouse, and Friend of the Court.

Of participants attending the Eaton County SMILE program (experimental group only), 94.2% indicated that it had been somewhat to extremely helpful, with 30% of the sample saying the program had been extremely helpful. Only 6% indicated that it had not been helpful to them. Similarly, 91% of respondents felt the SMILE newsletters series had been helpful.

Children's reactions to divorce. Examination of group and gender differences relative to the three factors, acting out, emotional neediness, and psychological adjustment, revealed no significant differences.

Discussion

From the perspective of the 183 parents who participated in this study, those attending the SMILE program were significantly more likely to communicate positively with their ex-spouses, a primary objective of the program. No other inter-group differences were found, supporting earlier studies of other short-term programs targeted toward divorcing parents (Kramer & Washo, 1993; Buehler, Betz, Ryan, Legg, & Trotter, 1992; Stolberg & Garrison, 1985). This one finding—the ability of SMILE participants to communicate in a more positive way with an ex-spouse—is an important one, for it signals a key characteristic of families who are generally healthier and less characterized by hostility. When parents can recognize the importance of cooperation and positive communication in their interaction with one another following marital transition, the potentially negative effects of divorce conflict on children can be minimized greatly. Re-education in feelings of hurt and restoration of a sense of trust can also take place more quickly in all family members.

Other findings in this study reinforce the idea that divorce is a very personal experience for every couple and for every individual. For example, perspectives and expressed needs of older respondents were quite different than those of younger respondents. The latter were less inclined to believe that children need to maintain strong ties with both parents, while older parents felt significantly different. It is difficult to sort out the reason for these differences. It could be that the pressures of parenting are quite different for those who have young children versus those who are rearing pre-adolescents and teenagers, causing parents with older children to recognize the value of an ex-spouse as a resource in dealing with more complex behavior in children or for shouldering more of the responsibility. It may also be that older parents, for one reason of another, are simply more knowledgeable in weighing the pros and cons of a child's continued strong ties with the non-custodial parent. Also, older children have greater ability than do toddlers and infants to express their wishes about maintaining a relationship with the non-custodial parent, which may contribute to more awareness on the part of parents. Older parents were also more likely to be aware of emotional upset in their children and to be more pessimistic about their children's ability to adapt to the family rupture. Again, this may be related to an older child's increased ability to demonstrate or verbalize stressful feelings and to act out in ways that are more worrisome to parents when less easily controlled. Older children's inability to adapt to a crisis such as divorce is often manifested in lowered school achievement, expressed anger and depression, and other challenges toward the custodial parent. As a result, parents of older children may receive more pressure than those with younger children by school personnel and the justice system when socially unacceptable behaviors and academic problems tend to become more noticeable and/or severe.

Just as older and younger parents were significantly different, male and female respondents reported experiencing divorce in markedly different ways. Though females were more likely to report higher stress relative to household, financial, and time management, males were more likely to note the importance of having children develop and maintain strong ties to a non-custodial parent. Males were also less likely to report negative divorce-related outcomes for their children. Considering all of these findings together, it is felt by these researchers that the highly significant gender differences found in this study are probably more related to custody status than to gender; however, this hypothesis could not be examined statistically, since too few fathers in this study had custody. Since most of the participating fathers did not have their children on a day-to-day basis, they may have been less likely to notice the kind of worrisome behaviors in children seen by mothers. Despite child support payments to their ex-spouses, they were also less financially burdened in general and did not report experiencing the drain on their time that the women caring for children were feeling.

Conversely, women with custody had the benefit of seeing their children wholistically and to witness a multitude of everyday positive and negative behaviors that contribute to a knowing intimacy between family members that is absent for those outside the "family circle." Women in the study did not report feeling they were losing touch with their children nor the stress of struggling to be a part of their children's lives, while this was a common theme revealed in the interviews of the male participants.

Recommendations for Future Programs

Parents participating in the SMILE program expressed the need to have more information available to them for dealing with toddler and adolescent behavior. These two phases in a child's life are, on average, more challenging for parents whether or not the biological family is intact, since fairly intense individuation on the part of the child is a developmental characteristic at these times in the life span. When the separation the child is striving for naturally is made more traumatic by a parent's abrupt departure and absence, the child's ability to adapt may be more problematic. While children's age-related reactions to divorce are identified in programs such as SMILE, it is felt that a more concerted effort to provide guidelines and strategies for modifying and preventing adverse reactions particular to certain age groups should be made by presenters. In addition, pamphlets specifically geared toward reactive behaviors in toddlers, school-age children, and adolescents—and effective adult responses to such behaviors—could be made available to program participants.

Media (radio, television, newspapers) in each community should be urged to provide information to the general public that goes beyond simply highlighting the negative effects of poorly-enacted family transitions; advice about dealing with common childhood and adolescent problem behavior and helping parents decide which professional advice should be sought would also be helpful. Parenting hotlines staffed by family and child development specialists was a suggestion made by a number of participants interviewed. Hotlines were seen as a potentially vital resource in all communities, not only for divorcing parents but also for other parents, educators, and day-care providers confused about how to handle difficult and/or out-of-control behavior in developing children. A hotline would also be helpful for unanswered questions parents wanted to ask during their attendance at a structured program but were reluctant to do so because of personal embarrassment.

Seeing children only on weekends and holidays also may lead to difficulty in knowing what their changing interests are or what to do with them during visitations. Borland-Hunt (1992) suggested that even the term "visitation" creates a mind set that minimizes the parenting time and interactions of the non-custodial parent, contributing to the feeling that the divorce ends the parent-child relationship as well as the marital relationship. While the quality of time spent with parents has more significance in a child's development than any other factor, parent-child interaction for the single parent may seem strained and unnatural because there is a constant getting-acquainted-all-over-again and let's-get-ready-to-break-it-off-again component in these relationships that is missing in the custodial parent-child relationship. Dr. Doris Jonas Freed, chairwoman of the Custody Committee of the American Bar Association and an advocate for joint custody, has suggested that visiting rights are not enough to allow for satisfactory continuing contact for non-custodial parents. They tend, she noted, to become "zoo" or "movie" parents (Coy, 1982). Because single custody continues to be awarded in the majority of cases, there are a number of strategies that could be shared in programs like SMILE to help non-custodial parents and children share the kinds of experiences and interests that bolster closer relationships and communication. These include writing letters regularly (perhaps using distinctive stationery that children recognize immediately) and sharing current "nitty-gritty" information that can be used as a basis for future discussions and on-going intimacy. Some non-custodial parents and children play games via mail or send jokes, cartoons, or pictures they think one another might enjoy. They have frequent, brief telephone conversations with their children, figuring that the opportunity to talk over special moments and problems and the special dimension of hearing the other person's voice are worth any cost of the calls. They utilize such technology as inexpensive cassette tape recorders or more costly video and send messages such as reading or telling a story or poem. They take a variety of pictures of everyday events and special moments to share via the mail.

When interviewed, the study parents centered frequently on custody issues and indicated a need for more guidance in this area. Poor outcomes for families following divorce can almost be predicted when one or both parents fail(s) to make a reasonable adjustment to the custody decision. When a non-custodial parent's attitude toward loss of custody remains one of intense disappointment or anger, or the parent was unstable or a poor parent to begin with, it becomes easier to dump all parenting responsibility in the lap of the custodial parent, including financial responsibility and total child care. The result can be severe stress overload in the custodial parent due to overwhelming economic and psychological responsibility and a marked decline in any leisure time or positive social interaction. Unless a custodial parent can quickly build new support systems in friends, the extended family, or the community, the chronic stress generated in this kind of situation will eventually impact on the physical and/or mental health of the responsible parent. Parent burn-out or apathy may likely result. Moveover, custodial parents who make visitation extremely difficult for the non-custodial parent because of unresolved anger may actually promote the kind of situation just described, thereby increasing their own problems and distress levels in their children and ex-spouse. Some couples also bounce in and out of court, spending a great deal of their psychic and financial resources over continued custody disputes to maintain or alter, at all costs, the initial decision. Often, there is an effort on the part of one or both of these spouses to continue to exploit or manipulate one another even after legal dissolution of their marriage.

There are cases where it would be beneficial to re-evaluate a prior custody decision because of changing needs in various family members. Perhaps the custodial parent simply needs a rest from parenting responsibilities or needs to put more energy into a job or career than earlier. Children grow older and may find one parent more satisfactory in fulfilling their needs at a particular time. It has been suggested that when children become adolescents and are struggling to organize their own identities, it is helpful for them to be with their same-sex parent. Also, as has been previously discussed, unless a child's safety is involved because a parent has been found to be unfit or irresponsible, children can only get to know their parents intimately when they live with that parent on a daily basis, watching attitudes, values, and coping skills being put into practice. For these reasons, custodial parents need to be considerate of the child's developing needs and best interests in periodically reassessing whether or not they are able to provide the best possible environment for that child at a particular time in the family's life span (Soderman, 1984).

It is important that the situation be viewed objectively from every perspective if couples are to work themselves out of damaging patterns that evolve. As a preventive measure, discussion relative to custody conflicts should be made a regular and important part of programs such as SMILE. In addition, more research is needed to look closely at how custody decisions are being made, as well as the types of safeguards and supports that are built in for both custodial and non-custodial parents to ward off financial and psychological stress. As more fathers take on the role of the custodial parent, we can begin to gain needed information about whether the heightened stress seen in female respondents in this study is in fact, related to gender or custodial status. Whenever custody is contested, Buehler and Gerard (1995) have suggested that there should be a presumption favoring shared custody, sole physical custody to the primary caretaker, and children's substantial access to the nonresidential parent unless there is convincing evidence that this arrangement is not in the best interest of the child.

When examining respondents' stress relative to dealing with the court system, Eaton County parents were more likely to experience less frustration than those surveyed in Clinton County, though differences were not statistically significant. These differences were also apparent in the interviews. Study participants also cited the need for change in the Friend of the Court. Parents are often unaware of the significance of the term, Friend of the Court. They believe that this office should provide support for parents who are going through the process of divorce, while, in truth, the primary purpose of the Friend of the Court is to reinforce decisions of the court. A critical need for reform was suggested by parents who were interviewed. In a recent Senate subcommittee report to look at needed changes in Michigan's Friend of the Court operations (Borowski, 1994), there were five recommendations to make the court more accountable: (a) a citizen's advisory board—including parents—to be created for each Friend of the Court office; (b) the creation of a special staff position to investigate and respond to all complaints; (c) to make it a felony to knowingly file a false claim of child abuse or not to report all income when required to pay child support; (d) to require sensitivity and stress management training for Friend of the Court workers; and (e) to have all forms and brochures to explain office policies, bills and statements in "plain English." In turn, the Michigan Friend of the Court Association, made up of the heads of each of the 63 Friend of the Court offices, asked for more authority to resolve the problems they encounter daily with the system's 750,000 cases.

As was concluded in an evaluation of the Children First program, a similar intervention effort with divorcing families (Kramer & Washo, 1993), the results of this study would support the growing number of states mandating participation in such educational programs as SMILE. Statutes such as the 1990 Marriage and Dissolution Act 404.1 in Illinois that gave judges in that state the prerogative to order divorcing parents to attend educational programming may have set a healthy precedent, given the continuing high divorce rate in the United States. Though a few of the respondents interviewed in this study indicated distinct displeasure at the mandatory nature of the program, they also indicated that they probably would not have attended if they had not been ordered to do so and, subsequently, found it highly beneficial. Kramer and Washo (1993) suggested that research is needed to examine whether or not parents would volunteer to attend such programs. On the other hand, there were large numbers of participants who did not voice any objection whatsoever to the court's request; many wished that they had been able to attend the program earlier in their divorce because they may have avoided some problems if they had received the information earlier. A few of the respondents indicated that the information had caused them to rethink their decision about whether or not divorce would be the best thing for them and their children—and that such a program might, in fact, ward off the heavy numbers of divorces.

Because some parents indicated that they had wanted to ask questions but did not because there were neighbors and ex-spouses in attendance, opportunities to ask questions anonymously while attending must be built into programs such as SMILE. By simply supplying cards to those attending before they are seated, participants can write questions as they are sparked by what is being said. The cards could then be dropped into a box and reviewed quickly by presenters during the coffee break provided for participants. The procedure would provide an opportunity for program presenters to respond to the audience's major, unvoiced concerns before adjournment. Respondents also felt that programs such as SMILE ought to be offered more frequently in communities and advertised to the general public, since they believed that there might be persons in the very first stages of considering divorce who may work harder on reconstructing a poor marriage, given knowledge of the potential consequences to children when the biological family unit is permanently ruptured. They also suggested that grandparents and educators could benefit by attending such educational programs.

Implications from this study are many for both family life educators and for professionals in the judicial system. Whether or not courts make the decision to mandate participation in such programs, families who are experiencing structural transition need information that can help them make the kinds of decisions and adjustments that will result in the ability of all family members to relate to one another without conflict in the future. Divorcing parents need to have this information available to them early in the decision-making process, and some will need on-going, follow-up support. Community sources of such support should be clearly identified to program participants.

Content of conflict prevention programs such as SMILE needs to be considered carefully, since only so much information can be offered in a two-hour or four-hour block of time. Subsequent research should be undertaken to look at the short- and long-range effectiveness of the variety of formats available and the kinds of information shared with participants who attend. As the structure of these programs evolves, on-going evaluation that focuses heavily on all family members' perspectives and gains will be a necessity in the shaping of truly effective educational offerings for transitioning families.

References

Aro, H. M., (1992). Parental divorce, adolescence, and transition to young adulthood: A follow-up study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 62(3), 421-429.

Borland-Hunt, D. (1992). Visitation: Guidelines for healthier co-parenting. Michigan Family Law Journal, Special Edition, 19-21.

Borowski, G. (September 1, 1994). Plan Retools Friend of the Court. Lansing State Journal, Al, 2.

Buehler, C., Betz, P, Ryan, C. M., Legg, B. H., & Trotter, B. B. (1992). Description and evaluation of the Orientation for Divorcing Parents: Implications for post-divorce prevention programs. Family Relations, 41, 154-162.

Buchler, C., & Gerard, J. M. (1995). Divorce law in the United States: A focus on child custody. Family Relations, 44, 439-458.

Camara, K. A., & Resnick, G. (1989). Styles of conflict resolution and cooperation between divorced parents: Effects on child behavior and adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 50(4), 560-575.

Coy, P. (October 11, 1992). Joint Custody Rare in U.S. Divorce. Lansing State Journal, 3D.

Elkin, M. (1985). Plugging the hole in peoples' souls: When divorce comes. Conciliation Courts Review, 23(1), v-x.

Emery, R. E. (1988). Marriage, divorce and children's adjustment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Farmer. S. T. (1993). Support groups for children of divorce. American Journal of Family Therapy, 21(1), 40-50.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Allison, P. D. (1989). How marital dissolution affects children: Variables by age and sex. Developmental Psychology, 25, 540-549.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Nord, C. W. (1985). Parenting apart: Patterns of childrearing and marital disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47, 893-904.

Grych,J. H. & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Interventions for children of divorce: Toward greater integration of research and action. Psychological Bulletin, III:3, 434-454.

Gullotta, T. P. (Winter, 1981). Children of divorce: Easing the transition from a nuclear family. Journal of Early Adolescence, 1(4), 357-364.

Hall, C. W., Beougher, K., & Wasinger, K. (July, 1991). Divorce: Implication for services. Psychology in the Schools, 38(3), 267-275.

Hetherington, E. M., Stanley-Hagan, M., & Anderson, E. R. (1989). Marital transition: A child's perspective. American Psychologist, 44(2), 303-312.

Kalter, N. (1990). Growing up with divorce. New York: The Free Press.

Kramer, L., & Washo, C. A. (1993). Evaluation of a court-mandated prevention program for divorcing parents: The children first program. Family Relations, 42, 179-186.

MacKinnon, C. E., Stoneman, Z., & Brody, G. H. (1984). The impact of maternal employment and family form on children's sex-role stereotypes and mothers' traditional attitude. Journal of Divorce, 8, 51-60.

McKane. M. L. (1991). Split identity and children of divorce. Family and Conciliation Courts Review, 29(1), 63-72.

Meyer D. R., & Bartfield, J. (1996). Compliance with child support orders in divorce cases. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 201-212.

Robin, A. (1988). Divorce timing. In A. R. McCarthy, & P. B Peart (Eds.), Michigan PTA Parents' Answer Book. Royal Oak, MI: Bridge Communication.

Shaw, D. S. (1991). The effects of divorce on children's adjustment. Behavior Modification, 15(4), 456-485.

Soderman, A. K. (1984). Divorce and Family Stress. Extension Bulletin E-1733. East Lansing: Michigan State University Bulletin Office.

Spigelman, G., & Spigelman, A. (1991). Hostility, aggression, and anxiety levels of divorce and nondivorce children as manifested in their responses to projective tests. Journal of Personality Assessment, 56(3), 438-452.

Stolberg, A. L., & Garrison, K. M. (1985). Evaluating a primary prevention program for children of divorce. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13, 111-124.

Wallerstein, J. S. (1991). Tailoring the intervention to the child in separating and divorcing families. Family and Conciliation Courts Review, 29 (4), 448-459.

Wallerstein, J. S., & Blakeslee, S. (1989). Second chances. New York: Ticknor and Fields.

Wallerstein, J. S., & Kelly, J. (1980). Surviving the breakup. New York: Basic Books.

Zill, N., Morrison, D. R., & Coiro, M. J. (1993). Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 7(1), 91 - 103.