Fostering Reasonableness: Supportive Environments for Bringing Out Our Best

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

19. Engaging People in the Design of Landscapes

Abstract

Landscape architects are often leaders in creating vital open community spaces. Early pioneers in the profession such as Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., Jens Jensen, and others sought to create public parks and gardens that would serve important social goals in providing healthful green spaces for people to use to relax and for recreation (Beveridge, 1977; Beveridge & Schuyler, 1983; Grese, 1992; Taylor, 2009). The strengths of their designs came from years of observing how the public used outdoor spaces and from their vision for creating new democratic gathering spaces for public discourse, outdoor performance, or connecting with nature. As early leaders in an evolving profession of landscape architecture, they and their contemporaries developed an expert-based model whereby designers saw themselves as providing a work of art for their clients. New York City’s Central and Prospect Parks, created by Olmsted in collaboration with Calvert Vaux, are good examples of such parks treasured today as important community spaces of urban nature.

While Jensen’s work largely followed this expert-based model, the implementation of his last major public landscape design, the Lincoln Memorial Garden, begun in 1936, required engaging many volunteers. As a project by the Springfield Garden Club and the Garden Club of Illinois, the intent was to create a living memorial to Abraham Lincoln representing the native plant communities from places where Lincoln had lived during his childhood and adult life, namely southern Indiana and central Illinois. Starting with old agricultural fields on the shores of the newly created Lake Springfield, Harriet Knudsen and the other leaders of the Springfield Garden Club engaged schoolchildren from across the region to collect acorns and worked with garden club chapters across the state of Illinois to rescue wild plants for planting in the garden spaces. The broad engagement of community members led to a heightened sense of ownership of the Lincoln Memorial Garden that has been critical to its long-term success. It is not surprising that the Lincoln Memorial Garden remains one of the best-maintained public landscapes created by Jensen during his entire career (Grese, 1992).

One of the chief problems with the “designer as expert”[1] approach is that the resultant landscapes may or may not be embraced by the public that uses them regardless of how visionary they might be as physical designs. What made the Lincoln Memorial Garden markedly different was the engagement of a broad cross section of community members in the process of implementing the design. Among the key lessons in these historical examples is that listening to people and engaging them in the creation and care of landscapes can result in their being more readily embraced by the people who ultimately use them and can ensure that the places actually endure. For a designer wanting to leave a legacy, this can be a critical motivation.

Editors’ Comment: Such processes could be thought of as creating a supportive environment.

Often, however, approaches for engaging the public in the design process are overlooked in the training of landscape architects. This may be due to the relatively short time frame of academic design studio projects, lack of clarity of who constitutes the stakeholders for certain projects, or a general feeling that engaging input from nondesigners might reduce the vibrancy of design concepts explored by students.[2] The danger, however, is that design professionals leave their academic training with the perception that engaging people is not integral to their own role as designers. This can result in public spaces designed with little regard for the people who ultimately use them or frustration by both designer and community members late in the design process when designs become mired in controversy.[3] In this chapter, I reflect on personal experience in attempting to integrate community engagement in design teaching early in the careers of landscape architecture students at the University of Michigan in the context of the Reasonable Person Model (RPM) framework.

Valuing Participation in the Design Process

The degree to which we value participation in the design process raises several key questions. Is landscape architecture more of a fine art expressing the views and values of the artist, or is it more about practical problem solving focused on expressing community values? In “Creative Risk Taking,” Stephen Krog (1983) raises the question of “whether the profession’s works are to be a service to society or a commentary on society.” While many landscape architects and site planners likely see their role more as service rather than commentary, they also aspire to use artistic skills to create places where users discover new things about themselves and their relationship to others or to nature.

A second key question relates to how and when users and stakeholders are involved in the process. Following an expert model, many designers argue that their years of experience in creating public places and observing their use substitutes for the need to get input on specific projects. They feel that they can anticipate people’s needs and reactions and that the process of public surveys, focus groups, or meetings would complicate the process and make it more costly. For these designers, making public presentations of their design ideas near the end of the process is perfectly adequate.

Others would support engaging people early and at key benchmarks throughout the process of design. Randy Hester has long argued for a design process that engages members of the community and seeks their input throughout the process (1984, 1985, 1990, 1999). He cites numerous examples where designers have worked with local communities to better understand their resources and values to create designs uniquely suited to the social and environmental ecologies of a place (Hester, 1990). From his experiments over the years in engaging the public, he has suggested twelve steps in a Community Development by Design process, distinguishing each step as contributing to a designer’s knowing and understanding of a place or about “place caring,” that is, engaging people in the act of designing and/or choosing design alternatives (Table 19.1).

There is much coherence between Hester’s model and RPM as developed by Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan (1989, 1998, 2003, 2009). RPM provides a useful framework for explaining the value of engaging the public in design decisions. As suggested by the Kaplans, people can be reasonable, like to know, want to learn new things, and hate being confused or feeling helpless. Moreover, they want to feel that they have opportunities to have input into the environments that shape their lives. RPM is composed of three main domains of informational needs: model building, meaningful action, and being effective. The model-building domain refers to the mental models that people create to help them cope with reality and understand and function in the world around them. In considering changes to the environments where people live and play, they want to know and understand those proposals and how changes might affect their lives. Designers can use their visual representation abilities as experts to help people envision the possibilities for local environments and offer their own feedback and expertise. In Hester’s model, this includes elements of each of Steps 1–8.

| Hester’s Framework | Reasonable Person Model | |||

| Step | Description | Model Building | Meaningful Action | Being Effective |

| 1 | Listening | |||

| 2 | Setting goals | |||

| 3 | Mapping and inventory | |||

| 4 | Introducing the community to itself | |||

| 5 | Getting a gestalt | |||

| 6 | Drawing anticipated activity settings | |||

| 7 | Idiosyncrasies inspire form | |||

| 8 | Developing a conceptual yardstick | |||

| 9 | Spectrum of plan | |||

| 10 | Evaluating costs and benefits | |||

| 11 | Transferring responsibility | |||

| 12 | Evaluation after construction | |||

In terms of meaningful action, people want to know that their voices will be heard, their actions will contribute to decisions, and they will be treated with respect. In Hester’s model, each of the first three steps is part of enabling meaningful ways for people to share information. An effective engagement design strategy accomplishes all of these through techniques such as public surveys, workshops, and community meetings. Sharing inventory and analysis information back with the community (Hester’s Steps 4–6) provide checkpoints to ensure that designers heard information correctly.

Finally, being effective relates to how people handle levels of information to be able to process that information and make effective decisions. In terms of a designer trying to gain public input, it becomes essential that information be shared in clear and understandable ways and not be overwhelming. More information is not necessarily helpful. What is essential is for the designer to provide a clear framework for information that enables people to make informed and effective decisions. Use of drawings, clear tables, charts, maps, and diagrams can all be tools in sharing information (Phalen 2011; Chapter 21, this volume). In Hester’s model, Steps 9–12 incorporate ways that can address this domain.

The Design Studio as a Place for Experimentation

The design studio in the landscape architecture curriculum is often a place that allows for small experiments in the teaching of design concepts and methods for exploring design ideas. It is typically taught with a format whereby students develop design skills by working on real or imaginary projects under the guidance of the instructor. As students work on design projects, their work is critiqued by the instructor and/or guest critics and then refined. Projects can last an entire term, or class work might involve several projects, each lasting several weeks or less.

In my own teaching experience, design studios have provided fertile opportunities for combining community service with active teaching of design (Grese, 1995). Over my years of teaching landscape architecture at the University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources and Environment since 1986, I have had the opportunity to work with a number of community groups in Detroit and Ann Arbor where it’s been possible to have students engage community partners as part of the process of exploring design ideas. In most cases, the input from potential users provided a richer understanding of the context for the project and how the parks or gardens we designed might serve their particular needs. Students have the chance to build skills in listening to people and making them feel that their input will contribute in meaningful ways, in communicating design alternatives in understandable ways, and in synthesizing community input as part of the design process. In this way, design projects effectively become small experiments in participatory methods.

Incorporating community-based projects into design studios does have constraints. As noted earlier, most projects last only several weeks. This means that the logistics have to be carefully planned and schedules worked out with community partners. There is not a lot of time for building credibility and trust between community members and the students involved—something that can be critical in many projects.

Editors’ Comment: Building mental models takes time. By promoting participatory processes early in a student’s career, Grese allows enough time for such models to be built.

My design studios have involved students in the first year of their design curriculum. There are both pros and cons to embedding community involvement exercises at this early stage of a student’s design training. Are the students confident and mature enough in their design skills at this stage to fully appreciate and respond to the feedback they receive from community partners? Promoting participatory processes early in students’ careers allows for the time necessary for them to develop the related mental models associated with such approaches. In addition, engaging people in the design process becomes an acceptable part of gathering input and generating design ideas rather than serving as something that is only added to special projects. Doing this helps promote a transparent process whereby young designers are more self-aware and articulate about how they can generate design ideas with and gather feedback from community members. In the next two sections I describe some of these class projects and highlight some of the opportunities they afford for the landscape architecture students as well as the participants in the projects.

Designing for Children’s Play

Many of the community engagement projects I have run in my design studios have involved working with children and the design of play spaces or gardens directed toward children, although the processes we’ve followed apply to other ages and client types. I’ve found that students are quite adept at planning activities to engage children, and children respond readily to attention by the students. In addition, before planning workshops or listening sessions with children, we have typically talked in class about characteristics of environments designed for children and shared stories of the kinds of spaces we all enjoyed in our youth. I have often used Randy Hester’s (1979) article “A Womb with a View,” which details discussions with his students, and Talbot and Frost’s (1989) article “Magical Playscapes” as a way of getting students to think about children and places special to them. The following descriptions highlight a few design studio projects engaging children as part of the design process.

Emmanuel Community Center, Detroit, Michigan (1996)

Founded in 1990 as an outreach of Emmanuel Parish and the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan, the Emmanuel Community Center provides a variety of social services and outreach to a neighborhood in Detroit and Highland Park with large numbers of Chaldean/Arab and African American residents. I learned of the center’s program through Margi Dewar, a faculty colleague in the Urban and Regional Planning Program at the University of Michigan who had previously worked with them on some urban redevelopment and planning projects. We pursued each of the three projects that the center wished for us to address by dividing the second semester design studio class into three teams. Here I’ll report only on the project involving two vacant lots that the center wanted to turn into a community-built park for teens.

The center ran two programs for teens in the community: Girl Talk and Boys to Men. Our students met several times with the teens who had already been involved in cleaning up the two vacant lots where they wanted to create their park. On the first visit, the teens gave our students a tour of the neighborhood (Figure 19.1), pointing out what they regarded as key features—homes with vicious dogs, places where the teens liked to hang out, routes they walked, etc. On the second visit, students brought model-building materials and worked with the teens in small groups to identify elements they’d like to see in the park and arrange them spatially (Figure 19.2). Key features included a space for soccer, a basketball court, an area for dancing, and a small shop area for selling snacks. They thought that the snack shop would help raise funds for the park and for activities they’d like to plan. They also wanted areas for sitting and watching the various activities as well as a high fence or other control measures for keeping out vandals. One of the teens, a sixteen-year-old female who was the oldest in the group, had helped create the neighborhood playground when she was younger and offered to serve as the “synthesizer” for the group. She took ideas generated by the other teens and combined them into a summary model. My students then took the ideas and headed back to our studios in Ann Arbor to process what we had heard and return with a set of design proposals for the teen groups.

When we returned about two weeks later with design ideas in hand, the responses by the teens provided memorable lessons in design communication. The designs that veered too far from what the consensus had been for the park were largely ignored. Stylistic graphics were also dismissed. The teens gravitated to those student drawings that showed people like themselves participating in the activities they had asked to be included in the park. Most popular of all was the design by a student who ably integrated all of the key features the teens had wanted and illustrated his design through an aerial perspective and key sections and sketches that showed a vibrant game of basketball, other teens dancing, etc. The design was simple, and the graphics were easily understood—clearly two key themes that became lessons from the project and have been shown by Phalen (Chapter 21) to be important in design communication. Another student learned a lesson about graphic representation when the teens reacted badly to the faceless, nondescript people she had included as scaled figures. Thinking quickly on her feet, she brought out colored pencils and asked the teens to “fix” the drawing. They eagerly went to work reshaping the people to look like themselves, with appropriate clothes and hair fashions, and in the process took ownership of the student’s design.

Broadway Park, Ann Arbor, Michigan (1998)

The director of the university’s Arts of Citizenship program approached me about running a joint project with a local elementary school that would combine learning about local history, natural ecosystems, and design for public engagement. This led to a two-week exercise in community engagement in my first-semester design studio class. We partnered with a second-grade teacher at a local elementary school who was very interested in engaging her class in thinking about how people had settled the Ann Arbor area. Prior to our visits to the class, the teacher had shared stories about Ann Arbor’s history and prepared the children for the exercises we would be doing in the field. I was a bit wary about working with second-graders, fearing that they might be too young to become engaged with the project, but I was quickly proven wrong.

For my design studio students, I outlined key goals for the exercise:

- Learn how to “read” a site, analyzing its key features.

- Understand the context of the site in relationship to the surrounding community and along the Huron River corridor.

- Become good listeners to the children involved in the project, stimulating their imagination as to how the site could be used as well as our own imaginations.

- Develop skills as translators/interpreters of design ideas generated together with members of the community (in this case, children from the school).

My students also had access to historical materials about the site and its history as a park. The site was a narrowed place along the Huron River where the shallow water was easy to ford. As a result, Native Americans had long used this site as a crossing for a trail running between the Ann Arbor area and Pontiac, Michigan. As the town of Ann Arbor developed, the site became the juncture between two Ann Arbor communities—”upper town,” where the university and town center were located, and “lower town,” which from its earliest days vied to become a commercial center. Ultimately the Michigan Central Railroad located along the edge of what would become Broadway Park, and throughout much of the park’s history it became known as “Hobo Park” from the temporary encampments populated by people running the rails.

We visited Broadway Park first as a class to record our own impressions and then came back with the second-graders. We created teams, pairing two to three of my students with three to five second-graders. Students prepared for visiting the park with the schoolchildren by creating simple, easy to understand maps of the park and devising activities that would help the children articulate their impressions of the site. Such maps provided an exploration opportunity for the children. When visiting the site, the second-graders were fascinated by features that were at once partly creepy and mysterious but also fascinating. They were enchanted by the underside of the bridge over the river and the idea that trolls and monsters might live there. They were particularly intrigued by a wooded nook at the east end of the park being used by a homeless man for sleeping. The children were captivated by the idea of sleeping in the woods, hanging your clothes on tree branches, and cooking outdoors, with all of its references to a Huck Finn–type fantasy.

The next week, we returned to the school to work with the same teams for generating ideas of how to improve the park. For my students, one of the key creative challenges of the project was to design exercises for engaging the children in generating design ideas. Each team came up with different approaches for encouraging the students to express themselves—one used pictures from magazines and a collage approach for exploring how activities might be grouped on the site, while another had the children draw their own images and locate them on a map. Still other teams had the children create models, using an assortment of scrap materials we brought along. While I had intended that my students would take these ideas and generate their own designs for the park, we decided to end the project with the design ideas generated by the children. Our final presentation was a sharing of the work done by each of the teams. The children by then had taken such ownership of the project that they wanted to be the presenters. One young girl in the second-grade class who had been very quiet and shy at the start clearly had become very engaged through working on the project. When it came time for her team to present, she wanted to be the spokeswoman. Later her teacher told me how surprised she was at this, because prior to this project the girl had rarely spoken up in the class. I do believe that all of us were ultimately impressed at just how articulate these second-graders could be about public spaces, by their desire to be involved and help shape a park that would be used by everyone in the community, and by the leadership role they took if given the opportunity and provided with tools for expressing themselves.

Children’s Garden for Mott Children’s Hospital and Nichols Arboretum, Ann Arbor, Michigan (2010, 2011)

This pair of projects, conducted in consecutive years, involved students in the second semester of the landscape architecture program. It grew out of a desire to create a garden space between Nichols Arboretum and the new Mott Children’s Hospital that was being built about a block away from the entrance to the arboretum. As director of Nichols Arboretum, I wanted to encourage families and staff from the hospital to use our property as a place of respite to contrast with the pressures and stress of a hospital environment. Several key administrators and family advocates from the hospital were also interested in creating outdoor play spaces that would substitute for a rooftop playground on the old hospital that was being lost by the new hospital construction.

In the first year the studio class worked entirely with staff and volunteers at the hospital—namely doctors and nurses, family program specialists, and parents who volunteered in a family support program. We had only one opportunity to meet with hospital staff and parents, but the students heard very different opinions about what would be appropriate for the children’s garden from these two groups. While the doctors involved were committed to getting children—siblings and patients where possible—outside, they were very concerned about cleanliness and children not getting wet in fountains or water-play structures. They were insistent about safety and the limitations to strenuous activities and sun exposure that many of the children might have. The staff involved in family programs at the hospital expressed a desire for activities that would enhance existing programs in music and art therapy. The parents, in turn, offered views that gave students much greater inspiration. One parent in particular spoke about children in the hospital as having had a part of their childhood taken from them. She was particularly interested in spaces and facilities that would allow children to take physical risks, albeit limited, and regain a part of their childhood. The parents were much more interested in a variety of programming options for the site and for recognizing the needs of mobile children at the hospital who might use the garden in between treatments. Students in the class clearly took the comments from these parents to heart and created a variety of alternatives for the site that would engage individual children, their families, and staff from the hospital.[4]

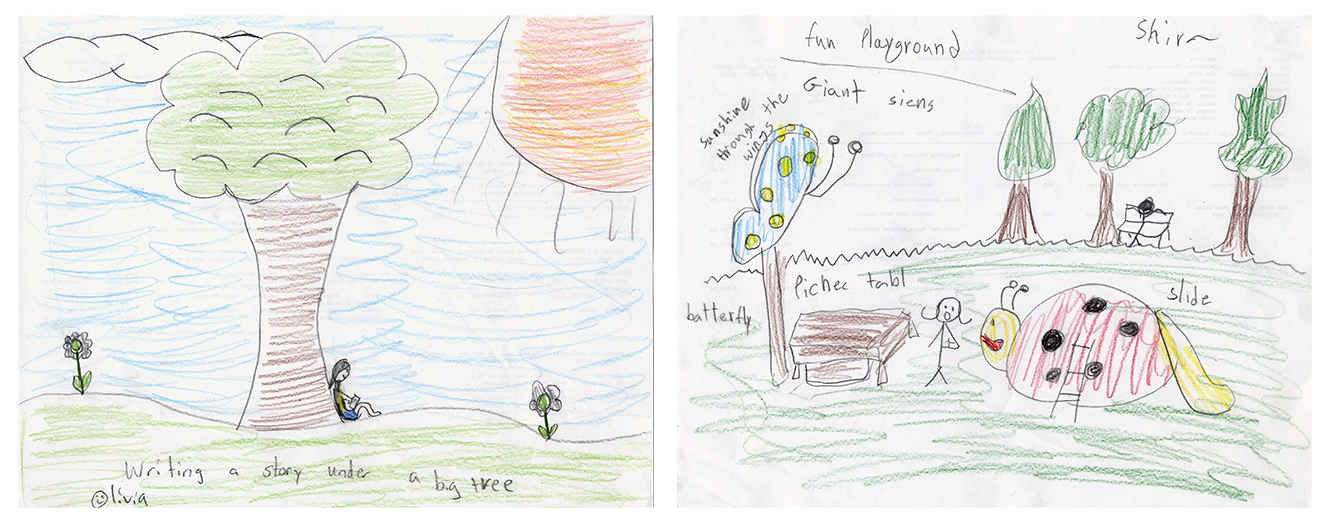

For the second year we worked with children from a nearby elementary school, including grade levels ranging from first to fifth grade, as the teachers and principal saw the exercise as a valuable way of getting children to think altruistically. The schoolchildren served as surrogates for children from the hospital, imagining what they would want to experience if they were patients at the hospital or had a brother or sister staying there. This class used a different place—a gently sloping site located between the arboretum and the main entrance to the hospital. As with the Emmanuel Community Center and Broadway Park projects described above, design students were paired with the children and planned activities that they thought would engage the children—drawings of features or environments that children would like to see included, photographs of features or spaces that children could sort through and arrange on a map of the site, and abstract three-dimensional models that children created of scrap materials.

Having the opportunity to engage these children directly resulted in a much greater range of design ideas and a strong sense of empathy for children in the hospital or for their brothers or sisters. The children’s conversations during the exercises became extremely revealing. In many classes, one or more children talked about spending time themselves in the hospital or about a sibling who had spent time there. Many of the older children, in particular, thought hard about how to make key features accessible. Tree houses where they could get up high, for instance, were immensely popular, and the idea of an extensive system of ramps excited many children. Other children wanted play spaces built into the ground—caves or “hobbit” houses. Most children included trees and flowers and features that reminded them of home. The student designs that incorporated these themes were among the most successful (Figure 19.3).

Working with Adult Stakeholders

Finding projects where there’s a defined adult constituency that can be done in the time frame of our studios has been more challenging than finding projects involving children. The following project, however, done with Glacier Hills Senior Living Community in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was an interesting exception.

Glacier Hills Senior Living Community, Ann Arbor, Michigan (1997)

The staff at Glacier Hills Senior Living Community in Ann Arbor approached me about the possibility of a landscape architecture design class assisting them with the design of a community garden space for residents. As with many senior communities, Glacier Hills recognized the importance of providing gardening activities for people’s physical and mental well-being and was interested in providing gardening spaces for residents. At the time Glacier Hills did have a small community garden space, but with mostly in-the-ground beds, many residents found these spaces difficult to use because of limitations to their strength, agility, and mobility. Our goal in the project was to suggest an alternative design for a garden space that would accommodate a range of physical abilities and gardening skills.

We began the project by holding a listening session with interested residents in early January. I divided the class into groups of two to three students who would meet with residents in small groups to learn more about their interests in gardening and the space being planned for the garden. When we arrived at Glacier Hills in the early afternoon, we found a relatively large group of residents well dressed for the meeting and patiently waiting for us in their large multipurpose room. After short introductions we broke into small groups, and students began questioning residents about their interests. It wasn’t long before the entire room was buzzing with conversation as residents reminisced about gardens they’d had in the past, shared frustrations with getting older and living in group living situations, and expressed hope about being able to use the new gardens. One woman spoke wistfully about sitting on a front porch at her old house listening to the rain on the roof. She wanted to be able to enjoy the garden in all types of weather and would enjoy a covered sitting area in the garden. One man who used the current garden to grow tomatoes thought there wasn’t much need for change. Others complained that he had taken over many of the available beds and wasn’t allowing enough space for others to get involved. Many commented on the difficulties they had in bending and lifting and expressed an interest for raised beds that would allow them to become more involved in gardening.

We went back to the design studio, talked about what we learned, and began developing conceptual designs for the new garden space. We met with residents at Glacier Hills again ten days after our first meeting and brought along the conceptual ideas students had developed. We broke into the same smaller groups that we had before, and students received enthusiastic feedback on their ideas. It was clear that talking about gardens and anticipating what the garden could be like was a highpoint in these residents’ long winter days.

In another week and a half, we returned with final drawings to share. Students set their drawings up on easels and talked with the residents who came up to view their work. Unlike our earlier visits, this time the conversations were more muted, and residents were markedly reserved in offering opinions and critique. A few of the residents commented to me how difficult it was to judge the students’ work; all the drawings were “so lovely.” When we got back to the studio, students were puzzled as to why the residents who had been so actively engaged in the first two meetings were so reticent to offer feedback on their final designs. The experience set the stage for a vibrant follow-up discussion in class about styles of drawings and strategies for sharing design ideas in ways that people felt you wanted their feedback. We decided that many of the student drawings were so precise and finely drawn that residents had been worried about hurting their feelings or that further feedback was unnecessary.[5]

Lessons from These Classroom Experiments

Each time I plan one of these participatory projects, I find that I learn something new about how to manage them as design studio exercises and how to make the experience useful for both the students in the class and our community partners. They are small experiments whereby the students and I learn about how much people like to be engaged and invited to give feedback, one of the key tenets of the RPM process. These design studio projects have become useful vehicles for students to learn firsthand how such feedback can enrich their design process.

Listening. Students learn key skills in listening to community members and in interpreting their mental models. In the projects described above, students explored a variety of techniques for hearing people’s concerns as well as their ideas for how to improve their neighborhoods or public spaces. For the project with Emmanuel Community Center, this involved taking a tour of the neighborhood with the teenagers involved with the project. In the case of Broadway Park as well as in the Mott Children’s Hospital Children’s Garden project, students were challenged to tailor maps that the children involved with the project could understand and then develop age-appropriate exercises for exploring design ideas with the children. For the community garden project with the Glacier Hills Senior Living Community, students learned skills in holding small focus groups and conducting small group brainstorming. All of these strategies for listening and recording ideas permit the students insights into the participants’ mental models (R. Kaplan, Chapter 2).

Dealing with expertise. Students also learn about the complexities that come with their role as experts in synthesizing ideas generated by listening sessions and translating them into imaginative design options. By building relationships with stakeholders early in the design process, designers can build a sense of trust that allows them freedom to advocate for ideas that might not otherwise be considered. By being involved early in the process, participants feel that their input can truly make a difference. This is especially important for groups such as children, teenagers, and elderly adults who are often not represented in many public participation efforts. In the projects discussed here, students discovered lessons about design communication and how to share their design ideas with various publics. At the same time, as the students learned the hard way in the Glacier Hills example, their expertise—that is, graphics that looked too finished—may actually make some groups feel that their input can no longer be meaningful if design decisions have already been made and thus shut down feedback. In contrast, graphic presentation techniques that show designs to be dynamic and open for continued refining may invite people to continue to be engaged. Similarly, in the teen park project with Emmanuel Community Center, students learned that inviting community members to revise or change drawings directly can help build a strong sense of involvement. These experiences help students understand that members of the public often process information differently and that design presentations can be tailored to encourage more reasoned and meaningful responses.

Fostering a sense of ownership. Finally, although these design exercises centered on the design phase of the projects, they provided strategies for beginning to transfer responsibility and ownership to community members, one of the key steps in Hester’s twelve-step process. In the teen park example, one of the girls assumed the role of synthesizer of ideas generated by other teens involved in the project. Similarly, in the Broadway Park project, the fact that the second-graders wanted to present the project designs themselves indicated a strong sense of ownership of the designs. These examples provided design students with firsthand lessons for creating meaningful roles for community members who have been involved in a community design process. Unfortunately, none of the projects described here have come to be built, allowing for the full transfer of responsibility and ownership to community members. This was not due to weaknesses in the designs or attractiveness of any of the projects but was instead due to a lack of funding or the needs of the projects being addressed in other ways.

Editors’ Comment: The adaptive approach that Grese describes is an excellent example of how small experiments can be used to improve curricula.

Adaptation and feedback. Despite these positive benefits for incorporating participatory design projects in studio classes, I’ve also learned that there can be challenges. Advance planning is critical. I’ve found the need to be flexible with my course schedule to the degree that I can to adjust the scope of a project, provide time for extra meetings if necessary, or make allowance for missing resource information when that happens. I also try to get regular feedback from students to ensure that the experience remains as valuable to them as possible. Whenever feasible, I try to engage students in planning the schedule and some of the dimensions of the project so that there’s a greater ownership of the entire process.

The most rewarding feedback is when I hear from former students that these community engagement projects shaped their perspective on design and gave them skills for working with community groups. My hope throughout all of these projects is to encourage a design process that incorporates the basic tenets of RPM, inviting members of the public to be active participants in creating supportive and environmentally sound places and communities. The creative phase of generating design ideas is far too much fun for designers not to share the process with others and broaden the range of ideas that can be considered for a particular site or a community. When designers redefine their role from that of an individual artist to one of a community facilitator who uses his or her artistic skills to give expression to community values, the resulting design solutions can be ever much richer. The end result can also be beautiful, healthful spaces that are readily embraced, supported, built, and used by members of the community.

Notes

1. Stephen Kaplan (Chapter 3) discusses the limits and benefits of expertise.

2. For further discussion of clarity, see Ivancich (Chapter 5).

3. Phalen (Chapter 21) explores processes for involving people in the design process. Petrich (Chapter 13) and Ryan and Buxton (Chapter 11) discuss the value of engagement in fostering attachment and a sense of ownership.

4. For further discussion about working with stakeholders with differing mental models, see Kearney’s (Chapter 16) discussion of the 3CM process and Hollett’s (Chapter 15) review of mediation. Monroe (Chapter 14) explores the engagement of stakeholders in natural resource management through similar sets of workshops and public meetings.

5. Duvall (Chapter 20) discusses strategies for engaging people, and Phalen (Chapter 21) reviews graphic presentation approaches that enhance engagement.

References

- Beveridge, C. E. (1977). Frederick Law Olmsted’s theory on landscape design. Nineteenth Century, 3(2), 38–43.

- Beveridge, C. E., & Schuyler, D. (Eds.). (1983). The papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Vol. 3, Creating Central Park, 1857–1861. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Grese, R. E. (1992). Jens Jensen: Maker of natural parks and gardens. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Grese, R. E. (1995). Reflections on community service learning in landscape architecture. In J. Galura and J. Howard (Eds.), Voices in dialogue (pp. 69–81). Ann Arbor: OCSL Press, University of Michigan, Office of Community Service Learning.

- Hester, R. T., Jr. (1979). A womb with a view: How spatial nostalgia affects the designer. Landscape Architecture, 69, 475–481.

- Hester, R. T., Jr. (1984). Planning neighborhood space with people. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Hester, R. T., Jr. (1985). Lifestyles and landscape: 12 steps to community development. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 75(1), 78–85.

- Hester, R. T., Jr. (1990). Community design primer. Mendocino, CA: Ridge Times Press.

- Hester, R. T., Jr. (1999). A refrain with a view. Places, 12(2), 12–25.

- Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Ryan, R. L. (1998). With people in mind: Design and management of everyday nature. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1989). The visual environment: Public participation in design and planning. Journal of Social Issues, 45(1), 59–86.

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (2003). Health, supportive environments, and the Reasonable Person Model. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1484–1489.

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (2009). Creating a larger role for environmental psychology: The Reasonable Person Model as an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 329–339.

- Krog, S. (1983). Creative risk taking. Landscape Architecture, 73(3), 70–76.

- Phalen, K. B. (2011). Evaluating approaches to participation in design: The participant’s perspective. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/86328.

- Talbot, J., & Frost, J. L. (1989). Magical playscapes. Childhood Education, 66(1), 11–19.

- Taylor, D. E. (2009). The environment and the people in American cities, 1600–1900s: Disorder, inequality and social change. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.