Fostering Reasonableness: Supportive Environments for Bringing Out Our Best

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

3. The Expertise Challenge

ABSTRACT

Experts are fascinating animals. But they are fascinating in a peculiar way. They know so much and can do such remarkable things. At the same time, they can be so frustrating and, not infrequently, just plain wrong (Cerf & Navasky, 1984). An old adage states that an expert is “someone who only makes big mistakes.” This side of expertise is brilliantly exposed in Scott’s Seeing Like a State (1998). This remarkable work deals with, among other things, massive agricultural reform programs. In all of these cases, the government took the decision-making role out of the hands of local farmers and transferred it to government-sponsored experts. These programs led to massive starvation; the only exceptions were in the few countries where the central government lacked the power to impose these expert-generated schemes on the populace. While Scott’s examples are all fairly dramatic, at one time or another many of us have had frustrating interactions with experts and have witnessed the contempt that some experts can have for the public.

From a theoretical point of view, the challenge is to find an explanation that can make sense of the apparently contradictory characteristics of experts’ great competence and failures. Watching an expert solve a problem with skill and efficiency, one cannot help but feel impressed. While considerable effort has been devoted to attempts to understand this awesome competence, far less interest has been expressed in the downside of expertise, even though this aspect is equally puzzling and perhaps of even greater practical significance. In this chapter we shall attempt to deal with both sides of this coin. Further, we shall attempt to demonstrate that their causes are not unrelated.

Features of Expertise

As it turns out, expertise is not magical or the result of extraordinary ability. Nor is expertise a generic quality that some people have and others do not. In fact, we are all experts with respect to some domains. In this section we explore how expertise develops and some of its key features.

Familiarity and Representation

Perhaps the most striking factor that sets experts apart from nonexperts is their familiarity with the content in question (R. Kaplan, Chapter 2) and their related ability to make sense of areas of enormous uncertainty. Experts are asked to determine what will make a sick person well, what will make a bridge cheap but safe, what will enable a school system to teach all its charges to read. These are problems where failures are rather visible and where causation is frequently obscure. There is much unavoidable uncertainty in these problems, yet expertise helps to reduce some of the uncertainty, place problems in a larger framework, and shows a path to a viable solution.

Experts develop a highly enhanced commerce with the objects of their expertise through different means. Formal training, one route to becoming an expert, entails many different ways of enhancing familiarity often involving instruction in where to look and what to think. Such training may involve reading case studies, struggling with projects, or perhaps even dissecting the results of other experts’ failures. Beyond the formal education stage there are often apprenticeships, internships, clerkships, and the like to further extend the experts’ familiarization. In some professions fledgling experts are then expected to work in the back room, to be a part of a larger office, to acquire even more of that priceless experience. Eventually professions permit their fledgling experts out on their own to acquire further experience with someone else’s problems.

Editors’ Comment: Formal training and personal experiences are full of the multiple, varied experiences required to build mental models. These are essential components of Ginsburg’s (Chapter 9) prison education program and, in a very different domain, Gallagher’s (Chapter 8) rural capacity-building programs.

Formal training is, of course, not the only means to becoming an expert; many skills that experts acquire are not ones that they were trained in but rather ones they have gained through their own experience. For instance, multilingual service personnel often have the ability to know what language to speak to an approaching customer even though the customer has not yet said a word. How do experts become so proficient at recognizing when and how to call on their specialized knowledge?

On the one hand, experts come into contact with the topic of their expertise so frequently that their superior familiarity is hardly surprising. On the other hand, however, just being in the presence of relevant objects or relationships is no guarantee of expertise. Familiarity accrued from being a passenger may not suffice when one needs to learn to navigate around town by oneself. Dedicated bird-watchers who have long studied birds with the aid of kayaks and binoculars are often extremely limited in their capacity to recognize birdsongs. Similarly, members of a local planning board were surprisingly slow in becoming comfortable and confident with their task (Kaplan, Kaplan, & Austin, 2008).

Editors’ Comment: In other words, small experiments help us develop expertise.

Active experimentation involving prediction and correction seems to be required in developing expertise. Trying things out, learning from one’s mistakes, and being active in the process all help to build a rich mental model of what works and what does not. In many cases, such learning is imposed by one’s environment or situation. Duvall’s (Chapter 20) engagement strategies are examples of structured experimentation. The motivation to achieve something can also foster the development of expertise. When confronted with a computer problem, compare trying to make guesses about what technical support might suggest rather than relying on them to tell you what to do when something goes wrong.

The familiarity gained through formal training, personal experience, and trial and error constitutes an enormous advantage in the way an expert approaches problem solving. The problem-solving process can be thought of as a search for a path between START and GOAL. START signifies the initial framing of the problem, and this depends greatly on the concepts, or representations, that are the building blocks of our mental models. They help us break a problem down into knowable parts and identify possible paths toward a solution. GOAL refers to this ultimate solution. Experts differ from nonexperts in how they initially perceive the problem as well as in their solutions.

As a consequence of extensive experience, the experts’ mental models provide the benefits of simplicity and essence. These are powerful assets to call on in a problem-solving situation. Their effect is so pervasive that it is hardly surprising that familiarity constitutes an enormous advantage in the way an expert approaches problem solving. Let us consider some of the ways this facility is beneficial in problem solving.

Where to focus? When one first confronts a problem—whether it is a sick tree or a faltering transportation system or a house plan that does not fit the budget—there is a potentially infinite number of things one could look at. It is easy to be overwhelmed without ever taking the problem any further. Having experience with a class of problems leads to possession of a set of mental models that gets one over this initial hurdle. Being familiar with a type of problem means that one knows where to start, that one knows what to pay attention to. Here the property of simplicity is particularly crucial, since a great deal of potential noise is eliminated. One is also depending on essence in that one is able to look beyond first appearances to the aspects of the situation that are likely to be critical. Thus, START is likely to be more clearly defined, since recognition of its salient features is greatly facilitated.

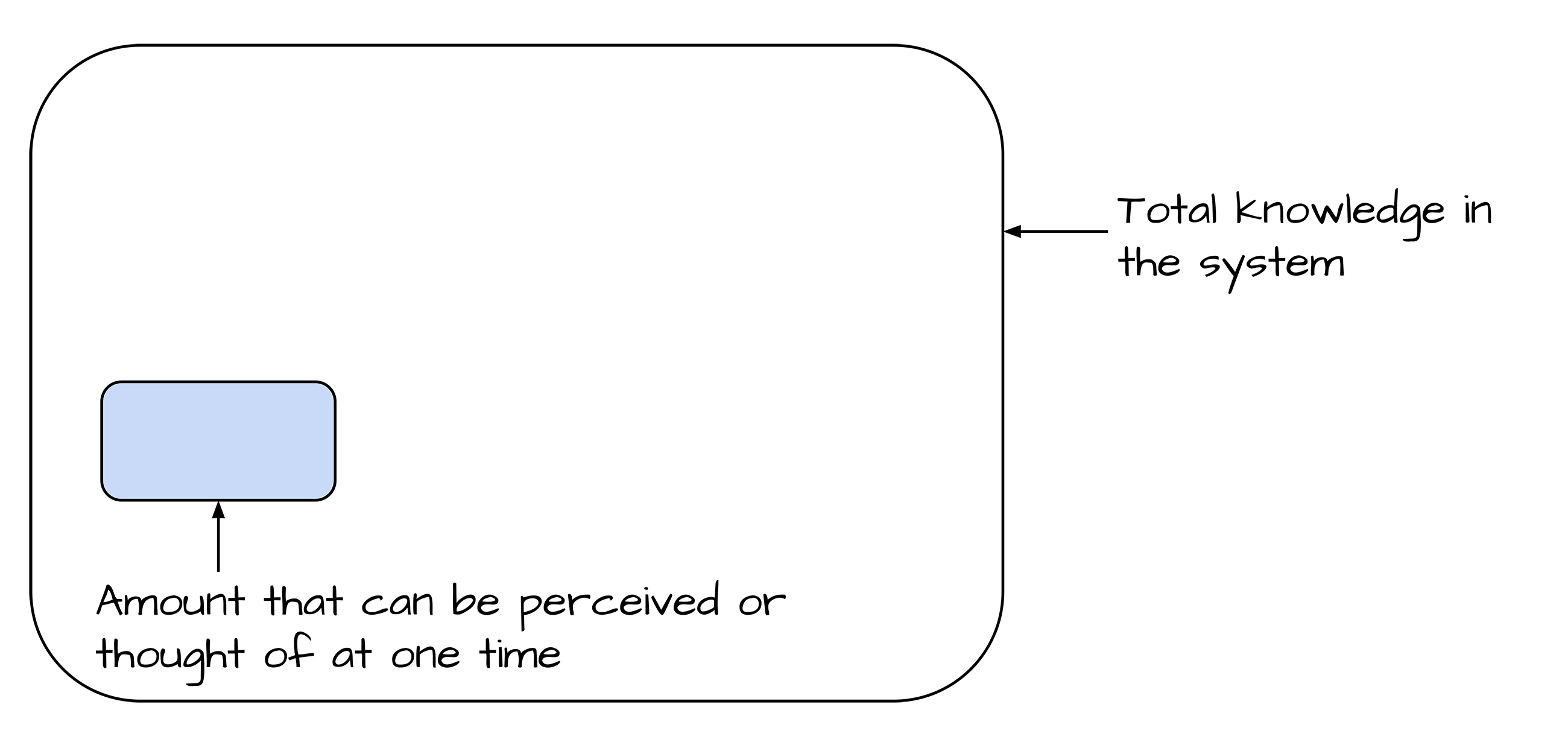

How much can one grasp at once? There are, as we have noted, a staggering number of different things going on in any given situation that might be pertinent to problem solving. So much is going on that it is unlikely that an individual can represent the situation in its entirety. The notion of “limited capacity” refers to the fact that only a small portion of all the knowledge that is stored in long-term memory can be active or in “working memory” at any particular moment. Figure 3.1 provides a graphic rendition of this state of affairs.

Source: S. Kaplan & R. Kaplan, Cognition and environment (1982, p. 165). (Reprinted with permission)

The limitation here is on how much of the system can be active at one time. This in itself does not determine how many different conceptual units—mental models or their components—can fit within that limitation. In order to answer that question, it is necessary to consider not only how many concepts comprise one’s mental models but also how compact they are.

Compactness

Most analyses of expertise emphasize that the learning process enables experts to group multiple elements so they can be treated as a unit, thus substantially reducing the burden on memory through reorganization of the elements. While such a chunking or unit-forming process is likely to occur, from our perspective the critical issue is that expertise also involves a reduction in the number of elements involved. In other words, we see the process as producing not only increased organization but compactness as well.

The coherence and greater ease of memory of these units are due both to a strengthening of connections among certain elements and a loss of other elements. A recently acquired representation is likely to be comparatively large. It would be diffuse and relatively disorganized, since the experiences on which it depends have not benefited from repetition. Clearly, not many such representations would fit within the limited capacity of the system. With increasing repetition and familiarity, however, relatively peripheral features are lost, and connections among those features that turned out to be more salient become strengthened. Thus, a well-learned representation will tend to be well organized and compact. The resulting representation, having benefited from familiarity, is more general and more economical of neural units at the same time. More of these well-learned representations would be expected to fit within the limited capacity of the system. In fact, for well-learned representations, the rule of thumb that some 5±2 units can be held in working memory at one time probably applies (Mandler 1975a, 1975b). How extensively one can represent a given situation thus depends on compactness, and compactness in turn depends on familiarity.

While the issue of whether the effect of experience is simply to better organize the elements of a representation or to actually reduce the number of elements involved might seem to be a rather technical matter of little practical importance, this is not the case. One of the hypothesized implications of increasing compactness is that experts come to possess greater channel capacity in the area of their expertise. This offers experts a substantial advantage. They can represent the situation more fully because well-learned representations are less demanding of limited capacity. The use of technical jargon takes advantage of such compactness, since for experts these labels are associated with well-learned representations. Thus, for example, the ability to recognize a seemingly arbitrary set of features (a learned perceptual capability) as aspects of “good conservation practices” (a label) achieves great cognitive economy, leaving room in working memory to examine additional aspects of the problem needing solution.

Another effect of compactness may be less advantageous. Due to the small size of the units, the number of units that can be active simultaneously, and the speed at which they operate, the mental process of the expert is far more difficult to access. It is typically automatic, intuitive, and inaccessible to consciousness. Cognitive processes also move quickly from the concrete to the abstract, thus making communication difficult with those who do not share these abstractions (e.g., the rest of us). After years of speculation about the basis of expertise, empirical progress was finally made on this intriguing topic with DeGroot’s (1965) research to determine what distinguishes the play of expert chess players from that of ordinary, though thoroughly competent, chess players. His conclusion was surprising. Master chess players used no special tricks or operations. Their patterns were exceptional in only one respect: their initial representation of the problem. In other words, the way they saw the problem gave them their advantage. DeGroot’s ingenious experiment involved asking chess players to reconstruct a pattern on a chessboard that they were allowed to view for five seconds. The master players were much better at this than were their less expert counterparts. This was true, however, only when the pattern viewed was a meaningful one, a pattern that could actually have occurred in a game. When the pattern was random, the master players completely lost their advantage. They were no better at seeing in general but were only better at seeing the patterns that matter in chess.

The key to solving a problem thus seems to lie in the way the problem is represented. One of the greatest assets of the expert is a more facile initial representation of the problem. While to novices it may seem that experts have some powerful techniques or special maneuvers at their disposal, it turns out that experts seem to depend more on facile representation and associative structures than on any special methods. Their familiarity facilitates the basic process of searching for a solution, a way to connect START and GOAL. This conclusion brings our analysis of the cognitive process full cycle. The formation of economical representations out of a diversity of overlapping experiences is a basic means of handling environmental uncertainty. This turns out to have its payoff not only in perception but in problem solving as well.

Costs and Benefits of Expertise

Being familiar with a problem domain thus has many advantages. In the area of their expertise, experts can more quickly feel comfortable in an unfamiliar situation. They possess mental models that allow them to see more readily aspects of a situation that are common to many other similar situations. They know what to look for and can grasp the problem more readily. Through more compact coding, more of the pertinent information can be represented at once. Finally, should manipulation of the parts of the problem be necessary, the experts’ familiarity provides greater facility in doing so.

There is, however, a price to be paid for all this facility and sense of confidence. The efficiency of expert problem solving depends on amply practiced perception, and such perception gains its efficiency through an astute ignoring of much that is going on. Although in some sense experts see more than the rest of us see, in another important sense they see less. This can be highly effective much of the time, but it can nevertheless create difficulties.

Sometimes solving a problem requires a new way of representing it, which in turn requires that one take in new information or see old information from a drastically different perspective. At such times, the differential sensitivity of the highly experienced observer may become a serious handicap. Decision makers and other experts are often extremely selective in the information they are willing to consider, to say nothing of information outside their expertise that they would be able to comprehend (Ingram, 1973; Ingram and Ullery, 1977; Jervis, 1973).

Editors’ Comment: This is but one example of how participation is often hampered by the nature of expertise.

Another difficulty may arise out of the very efficiency afforded by the compactness of representations. This can lead to a case of “hardening of the categories.” It is not unusual for an expert to diagnose a problem too decisively. Vast experience acquired across numerous specific instances may lead to a label being applied too hastily, leading to the decision to proceed with the “right” solution—namely, the one that has been applied numerous times in the past. Perhaps, too, this is the reason that so many parts of the country have lost their local distinctiveness. It has been the fate of many cities to see special places destroyed, as experts from out of town have been responsible for redevelopment projects.

The difficulties created by the expert’s greater facility with problem solving can be particularly disturbing in circumstances involving change. Being highly effective at picking out the crucial elements of a problem can become a handicap when what was once crucial is crucial no longer. In other words, when the nature of the problem itself changes, the expert may not be aware that all is not as it was. Another sort of change is even harder to detect and is therefore potentially more damaging. This involves a change in the larger framework. For example, a great deal of expertise about major economic activities was acquired during a time when materials and energy were cheap and their cost could be ignored. Today that framework has changed, making problem solving about issues such as farming and manufacturing entirely different. Yet many experts behave as if the implicit framework they grew up with still holds. There is little that is as frustrating as watching experts conduct business as usual while the world undergoes radical changes. It is perhaps because of this capacity to be oblivious to what is so obvious to others that an expert has been described as “someone who makes only big mistakes.” Thus, for some problems—particularly those where both START and GOAL are in the future—the nonexpert may be at least as likely to ask the right questions and find novel solutions.

While few treatises on cognition deal with the costs and benefits of expertise, concern for this issue is not new. Writing quite a long time ago, Laski (1930, p. 102) considered what he called “the limitations of the expert.” His context was foreign policy, and his message included an emphasis on the necessity of consultation with experts. Nonetheless, he was vividly aware of their limitations and articulate in his reservations:

But it is one thing to urge the need for expert consultation at every stage in making policy; it is another thing, and a very different thing, to insist that the expert’s judgment must be final. For special knowledge and the highly trained mind produce their own limitations which, in the realm of statesmanship, are of decisive importance. Expertise, it may be argued, sacrifices the insight of common sense to intensity of experience. It breeds an inability to accept new views from the very depth of its preoccupation with its own conclusions. It too often fails to see round its subjects. . . . Too often, also, it lacks humility; and this breeds in its possessors a failure in proportion which makes them fail to see the obvious which is before their noses. It has, also, a certain caste-spirit about it, so that experts tend to neglect all evidence which does not come from those who belong to ‘their own ranks.’ Above all, perhaps, and this most urgently where human problems are concerned, the expert fails to see that every judgment he makes not purely factual in nature brings with it a scheme of values which has no special validity about it. He tends to confuse the importance of his facts with the importance of what he proposes to do about them.

It might seem puzzling that the expert, who is so facile and impressive in so many ways, can also cause so much frustration. Alternatively, it might be the very strengths of the expert that are responsible. The core of expertise, as we have seen, is perceptual. While seeing things in a highly skilled fashion is quite obviously a powerful asset, it has a consequence that is often overlooked. Like the rest of us, experts do not perceive their own perception. All of us, expert and layperson alike, use perception to find out what is going on in the world around us. In other words, perceiving involves seeing the world, not seeing how we perceive. Further, we experience what we perceive as being a direct indication of that world. Therefore, what we see is what we assume is there. And since it is reality that we consider ourselves to be seeing, we also assume that any reasonable person would see the same thing.

In theory, this assumption causes little difficulty. However, if one sees the world very differently from the way others see it and counts on others to see as we do, the consequences can be unfortunate. If one is cold sober and sees an elephant grazing across the street, one expects others to see the elephant as well. If someone does not see it, it is hard to resist the thought that something must be wrong with that person. For most of us this happens rarely; for the expert it can be a common experience, leading to asserting that others are stupid or incompetent. Unfortunately, expertise is irreversible; it is rarely possible to turn the clock back and reconstruct how one saw things before becoming an expert.

Editors’ Comment: Nearly every chapter in the book provides examples of experts acting as facilitators that help nonexperts explore a problem space, including programs for forest owners to better manage their property (Bradley & Cooper, Chapter 12), rural citizens to learn civic skills (Gallagher, Chapter 8), farmers to reduce impacts of climate change (Monroe, Chapter 14), and children to design public spaces (Grese, Chapter 19).

It is apparently difficult to treat with respect people who fail to see the obvious. While the public’s perception may be limited in comparison with that of the expert, the public’s sensitivity to the condescending stance of the expert is often quite acute. The resulting negative reaction on the part of the public is sometimes taken by experts as confirming their worst suspicions. Thus begins the downward spiral that so often mars the public meeting where the experts present their findings to the “unappreciative masses.”

Fortunately, many of the potential problems of expertise can be circumvented, as shown throughout this book. To help experts (and that includes all of us in the areas of our expertise) realize the implicit dilemma of expertise, it would be useful if they were taught about the nature and hazards of expertise as part of their training to be experts so that they could better recognize and respond constructively to the struggle of the layperson to comprehend and participate. It is possible to build a mental model of the layperson even if one can’t become one again. By knowing what helps laypeople understand and contribute, such interactions could become as satisfying as they are now frustrating.

References

- Cerf, C., & Navasky, V. S. (1984). The experts speak: The definitive compendium of authoritative misinformation. New York: Villard Books.

- De Groot, A. D. (1965). Thought and choice in chess. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

- Ingram, H. M. (1973). Information channels and environmental decision making. Natural Resources Journal, 13(1), 150–169.

- Ingram, H. M., & Ullery, S. J. (1977). Public participation in environmental decision making. In R. Sewell & J. J. Coppock (Eds.), Public participation in planning. London: Wiley.

- Jervis, R. (1973). Minimizing misperception. In G. M. Bonham & M. J. Shapiro (Eds.), Thought and action in foreign policy (Proceedings of the London Conference on Cognitive Process Models of Foreign Policy). Interdisciplinary Systems Research no. 33.

- Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Austin, M. E. (2008). Factors shaping local land use decisions: Citizen planners’ perceptions and challenges. Environment and Behavior, 40, 46–71.

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1982). Cognition and environment: Functioning in an uncertain world. New York: Praeger. Republished by Ann Arbor, MI: Ulrichs Books, 1989.

- Laski, H. J. (1930, Dec.). The limitations of the expert. Harper’s Magazine, 162, 101–110.

- Mandler, G. (1975a). Memory storage and retrieval: Some limits on the research of attention and consciousness. In P. M. Rabbitt & S. Dornic (Eds.), Attention and performance, Vol. 5. London: Academic.

- Mandler, G. (1975b). Consciousness: Respectable, useful, and probably necessary. In R. L. Solso (Ed.), Information processing and cognitive psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgments

This chapter, originally titled “Expertise,” was prepared as part of a collaborative project with Leeann Fu and Mark Weaver. It incorporates substantial material from Chapter 7, “Problem Solving and Planning,” in S. Kaplan and R. Kaplan, Cognition and environment: Functioning in an uncertain world (New York: Praeger, 1982; republished in 1989). The editors have revised the chapter somewhat and have inserted references to other chapters in the book. The editors greatly appreciate the contributions to this revision by Jason Duvall, Eric Ivancich, and Anne Kearney and would like to thank Leeann Fu and Mark Weaver for their collaboration on the original version.