Fostering Reasonableness: Supportive Environments for Bringing Out Our Best

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

13. Fostering Sustainability through the Reasonable Person Model’s Role in Enhancing Attachment

Abstract

Frank Gehry’s remarks to a reporter (Heathcote, 2008) trigger questions regarding the notion of time in the design process:

We are temporary and so are all our structures. A few last through the ages with varying degrees of presence. Perhaps. . . . In the last year four of my buildings have been torn down . . . and I’ve been asked to defend them. I don’t. A building refers to its time, to the things it was responding to, the people, the place. It’s either useful or it’s not. And sometimes they’re not.

If one of the world’s great architects cannot outlive his own creations—losing four in just one recent year—what does that tell us about the pursuit of sustainable structures?

Demolition of buildings, however, is not so much a reflection that “architecture exists in a different layer of time; it is designed for the future, using the knowledge of the past but firmly in the present” (Heathcote, 2011). Developers, the more likely contributors to the fate of buildings, do not find making decisions about whether to rehabilitate, restore, repurpose, or tear down a structure to be troublesome. Demolition seems to be the default mode.

Survival analyses of building stocks are scarce, but the few extant studies are informative. Of 227 demolished buildings in Minneapolis–St. Paul, O’Connor (2004) found no significant relationship between durable materials such as concrete and steel and long service lives. Perfectly useful buildings were torn down because of changing land values (34%), lack of suitability of the building for current needs (22%), and lack of maintenance of various nonstructural components (24%). Only 8% of the buildings experienced structural failures.

Architecture may be “of its time.” However, the destruction of buildings runs counter to some key issues that relate closely to the Reasonable Person Model (RPM). In particular, in this chapter, I examine attachment and challenges in achieving sustainability in the built environment through softer factors such as land values and suitability for meeting human needs over time rather than structural failure, energy efficiency, or durability of materials. I discuss how people become attached to landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures, and I introduce an attachment matrix to help illustrate the process. It is here where we can see that attachment models, like other mental models, are simplified versions of reality and carry the inherent strengths and weaknesses of their analogical nature. We find that the essence of attachment is adaptivity over time. I describe how adverse changes to supportive environments reduce attachment and in turn limit meaningful actions and being effective. I conclude by examining the role that RPM plays in interrelationships among reasonableness, attachment, and sustainability.

Mental Models of Attachment

Attachment appears to be an important factor affecting a structure’s longevity. Anyone who has gone through the decision-making process regarding possessions when moving to a new residence after years in one place knows the intensity and complexity associated with the personal sense of attachment. We may realize that we are attached to something and then pause to wonder why. We may even pause to think about things we are not attached to or things we used to be attached to but are no longer.

Mental models of the attachment process, however incomplete and inaccessible to our everyday awareness, store the objects and events we have experienced—and our interpretations of them—allowing us to make predictions about possible outcomes:

“This isn’t working; we must change it” (exploring, tinkering).

“This isn’t working; we must start over” (with inherent implications to sustainability).

We innately craft such mental models; these inevitable creations are based in experience and repetition, both of which take time (R. Kaplan, Chapter 2). In this chapter, I posit that we effortlessly and nonconsciously become attached to environments that support our needs. I suggest that a matrix derived from form and function can be useful in explaining our attachment. This matrix also explains why we take meaningful action in caring for those environments that shelter and support us. As a result, we tinker with landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures to more closely align them with our need to (Basu, Chapter 6):

- make sense of situations,

- feel confident enough to explore solutions for poor adaptations,

- maintain a clear head, and

- undertake meaningful endeavors.

As happens with so many mental models, we are not likely aware of the reasons for our attachment and how they function in organizing our information appetites. We may or may not be able at any one time to effect desired changes in our environment as we seek the slippery, illusive alignment that defines environments to which we could become attached or are attached to. As we sense the attachment itch and are driven to scratch it, a by-product is that we create a more sustainable world.

In tinkering with environments to better fit our needs and thereby support reasonableness, we likely subconsciously deepen our relationships to environments to which we become attached and in turn steward (with resultant sustainability benefits). In this chapter I write of landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures, but I primarily employ architecture to illustrate how people nonconsciously use RPM to create and interact with environments that support human needs.

We each have our own idiosyncratic mental models—rooted in myriad individual experiences—of how landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures should look and function. These are tightly yoked to context, circumstance, setting, and other factors unique to each of us (Basu & Kaplan, Chapter 1). We are individually driven to tweak and experiment with our environments to shift them toward an internal, only inchoately envisioned future to which we think we can become attached (or more strongly attached) and that can better support our needs. Despite this individuality, we share generally similar mental models regarding which environmental contexts are supportive and adaptive.

According to Basu (Chapter 6), with time we become aware of patterns and experience sequences of thoughts, feelings, and actions such that “we learn to see what leads to what.” Our dawning awareness, Basu writes, helps us determine appropriate courses of action. As we experience more human environments and more diverse ones, we become better able to determine the essence of the patterns so that we are not misled by lesser contributing features.

Nearly thirty-five years ago, well-known architect and architectural theorist Christopher Alexander and his colleagues at the Center for Environmental Structure published in A Pattern Language the results of an epic study of archetypal solutions to recurrent problems in the built environment (Alexander, Ishikawa, & Silverstein, 1977). For example, pattern number 60, “Accessible Green” (one of the authors’ 253 patterns), likely resonates with the authors in this volume and with many readers:

People need green open spaces to go to; when they are close they use them. But if the greens are more than three minutes away, the distance overwhelms the need (p. 305).

The patterns, collectively, form a sensible language, which, as the authors say, “any person constructs for himself, in his own mind” (p. xvii). It is the ripples, and sometimes waves, that Alexander’s patterns have brought to the design arts that well illustrate the notion of mental models of desired human environments. The Alexander study provided a language to capture the ephemeral, difficult to articulate, heavily nuanced, and highly idiosyncratic sense of environments that support us in being our most reasonable selves. Again, individual patterns from a variety of people show surprisingly similarity.

No single environment can meet the needs of all people or of any one person throughout his or her life (Basu, Chapter 6). Because of this, we need to be constantly open to changing our settings so they better support our individual and collective needs. Our information-seeking curiosity means that we continually try to make sense of our experiences, connecting new information to what we already know. We tinker with solutions to problems we may be only vaguely aware of. Our needs and our environments will constantly change; similarly, the environmental expression of the most appropriate and supportive fit will need inevitable tinkering or re-creating. This pattern-making search for solutions is exemplified by the attachment matrix. This matrix offers insights into what we each likely construct as mental models of the built environment and into our inclinations to create that environment.

Form Follows Emotion: The Attachment Matrix

Emotional attachment appears to be an emergent property of people interacting with environments that please aesthetically and functionally. Commercial product designers consider emotion to be the differentiating dimension once functional demands have been met (Richardson, 2007): think VW Beetle or iPhone or iPad.

Product attachment (Richardson, 2002), a product’s “emotional afterlife,” is the Holy Grail of product design; it leads to product and brand loyalty. A consumer’s successful experiences with a product follows progressive steps (designers call it the “emotional timeline”): alignment with the product that deepens into engagement, which must be satisfied with appreciation of the product’s utility, which is followed by attachment.

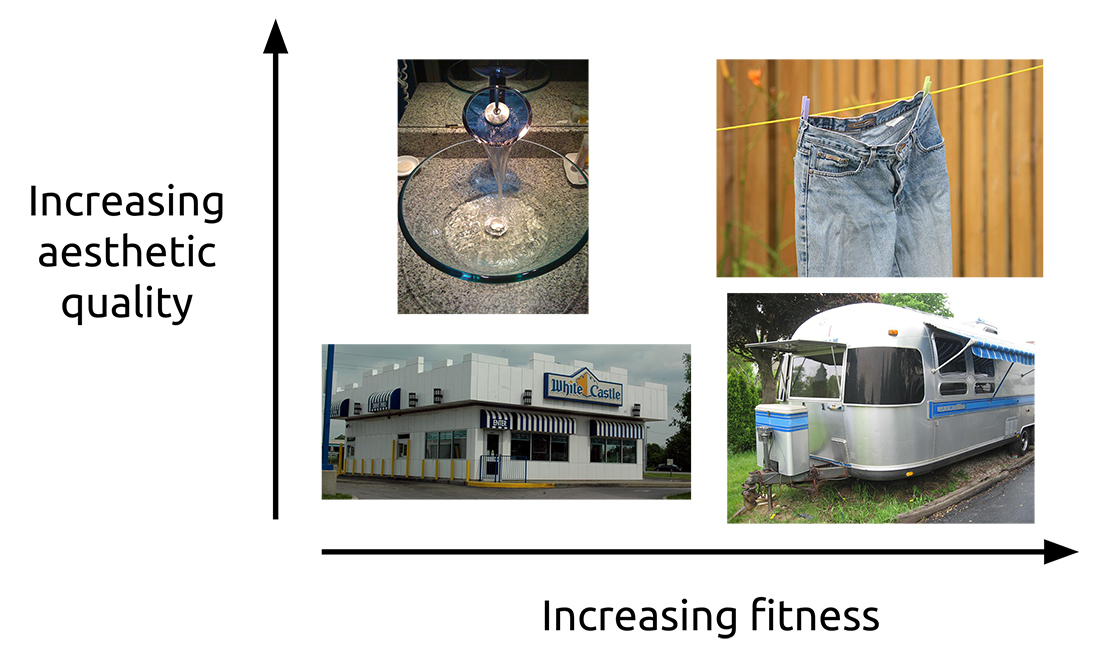

I modified this continuum to explore the partially overlapping space occupied by form and function in the built environment. I created a 2 x 2 matrix, arraying aesthetic quality (form) in the vertical dimension against fitness (function) in the horizontal (Figure 13.1). This attachment matrix facilitates envisioning the interaction between form and function as the two stimulate progressively stronger emotions. One experiences alignment when the current environment has minimal utility and merely acceptable aesthetic quality. As one becomes increasingly attracted to aesthetic properties of a landscape, space, city, or structure, one can be said to be engaged with it. While becoming increasingly pleased with an environment’s functional fitness, one experiences the satisfaction of emotional utility: a feeling not just of not being frustrated but of delighting at how something meets or exceeds one’s expectations in terms of operational performance. (When we hear people say, “This television works beautifully,” they are marveling about how far to the right the television is in the utility quadrant, not about its aesthetic quality.) When an environment pleases through its attributes of both aesthetic quality and fitness, it can be said that one has become attached to it. With attachment, one can glimpse sustainability.

To grasp attachment, consider one of its most illustrious exemplars: Levi’s blue jeans. In How Buildings Learn, Brand (1994) makes the case for jeans being the one garment in the world with “the greatest and longest popularity” (p. 11). For more than one and a half centuries, blue jeans have proved durable, elegant beyond fashion trends, and adaptable; they are revered throughout the world by people of all ages. The average American owns seven pairs (Thomas, 2005), each in a different stage of its life cycle. Usually only one pair at a time is at its peak of wearability, fit, and appearance. We all eventually learn that it is a Sisyphean task to keep that single pair we are most attached to at the peak of its life cycle. Product designers refer to jeans generically—and particularly that single favorite pair to which we become so attached—as “emotionally durable” (Chapman, 2006):

Purchased like blank canvases, jeans are worked on, sculpted and personified over time. Like a second skin they are lived in, faded and bulged by our experiences. Jeans are like familiar old friends; the character they acquire provides reflection of one’s own experiences, taking the relationship beyond user-and-used to creator-and-creature. To intensify the sense of creation further, people rip their jeans, cut them with knives, scrub them with a yard brush, bleach them and throw paint over them.

What impresses Brand most is that jeans show their age honestly. He sees blue jeans as “highly evolved design” (p. 11) with many imitators, each failing to measure up to the original. Any of us can immediately identify ersatz-aged jeans as failures. Only weeks of wear and time’s successive washings can create the precise color and texture and fit of our favorite pair of well-aged jeans, however personally ephemeral that pair’s status. In what becomes the de facto thesis of his book, Brand (p. 11) asks, “Are there blue-jean buildings among us? How does design honestly honor time?” I will return to the role that time plays in attachment.

Figure 13.2 illustrates application of the attachment matrix to everyday objects. Fast food restaurants minimally align with our expectations—that is, they “get by” in terms of appearance and provide the intended functionality. An Airstream trailer is few people’s ideas of an aesthetic treat, but its solid success over the years and its ranks of committed users attest to a superb achievement in meeting fitness expectations. The glass washbasins we now frequently encounter represent engagement well. Remember when guests were uncomfortable wrinkling the hand towels in the guest bathroom? Now they are also afraid to leave water spots on the beautiful glass bowl and therefore perhaps leave hands unwashed. So, the glass basin is the shiny must-have that thoroughly engages the senses—for now—while only minimally meeting fitness criteria. It is the equivalent of whatever a couple of people shopping are looking at when you overhear one say, “It’s lovely, honey, but would we ever use it?” Of course, finally, blue jeans reflect the twin goals of outstanding aesthetic appearance and the quintessence in fitness and comfort.

Stewardship and Caring

Consider landscapes as illustrative of the power of caring for environments for which we feel attachment. Nassauer (2007) has advanced the idea that landscapes that attract admiring affection—care—are most likely to survive. She calls landscapes whose longevity depends on human attention “culturally sustainable” (p. 365). Outstandingly beautiful landscapes tend to insist on being protected by attracting deep emotional attachment. Such landscapes are relatively rare, their scarcity in itself contributing to their high appreciation. Attractive landscapes, on the other hand, tend to display evidence of stewardship. We can find “display of care” (p. 364), as Nassauer terms it, in even the most ordinary landscapes. Through good intentions, personal pride, a work ethic, and a sense of contributing to community, people steward at least some of these landscapes (Nassauer, 2007). She observes that when landscapes are cared for (and cared about), people are less likely to “redevelop, pave, mine, or ‘improve’” (p. 365) them.

These landscape observations align with O’Connor’s (2004) findings regarding the longevity of the Twin Cities’ building stock on those occasions when adaptivity is a viable option capable of trumping changes in land value and land use. Adaptivity has a better chance of being a viable option when people care enough about the landscape, space, or structure in question to make the case for its adaptive reuse. Deeply held mental models of attachment can fuel the process of creatively and meaningfully exploring alternatives to demolition or passive tolerance.

Built environments ultimately do have limited, variable life spans. They are all subject to the vagaries of shifting contexts, land uses, land values, and tastes. How many midwestern towns have atrophied after having been bypassed by freeways? In just the past thirty years, the plaza in front of New York City’s Jacob K. Javits Federal Building has undergone implementation of three completely different designs (four if you include an interim space-holding configuration), each a product of a well-known design team, beginning with Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc. The repeated restructurings of this public space are more a reflection of ordinary people’s—the users’—dissatisfaction with designers’ intentions than of changing uses or valuation of the surroundings. A sense of attachment failed to develop with each of the first three designs, and it is too soon to tell with the latest one. With the Javits plaza, the users were not the ones to do the tinkering, but it was they who insisted that celebrated designers continue to rework the plaza design. Perhaps smaller exploratory design attempts might have yielded more satisfactory and sustainable results more quickly and with less resource consumption.

Ryan and Buxton (Chapter 11) recount the heightened sense of ownership and responsibility in Boston’s community-greened spaces. These spaces are not only well cared for but are also less vandalized than nearby public spaces, including public parks and schools. As Ryan and Buxton note, choosing to take care of an important place seems to cause users to feel effective in their immediate world.

Sheppard (2001, p. 159), in what he terms a theory of visible stewardship, furthers the notion of our liking those things

that clearly show people’s care for and attachment to a particular landscape; in other words, that we like man-modified landscapes that clearly demonstrate respect for nature in a certain place and context. This theory emphasizes not whether the landscape looks natural, or orderly, or culturally appropriate, or controlled, so much as whether it looks as though real individuals care for the land or place; people who are linked to it, rooted in it, invested in it, working in a respectful, symbiotic, and continuously vigilant manner, perhaps even from generation to generation.

In Grese’s account (Chapter 19) of the Lincoln Memorial Garden in Springfield, Illinois, tight budgets and a multidecadal time horizon created collaboration between schoolchildren and garden club members. It is not difficult to imagine the sense of ownership—and attachment—in one of today’s park volunteers saying, “When my grandmother was in the third grade, she gathered acorns for that row of burr oaks you can see on the far side of the meadow.”

Sheppard’s notion of visible stewardship resonates with the discussion of how effectiveness, in RPM terms, means seeing the bigger picture (S. Kaplan & Kaplan, 2009). Choosing actions that one thinks will be most effective is based on understanding—at some higher level—what is going on. In other words, it relies on mental models based on years of experience in diverse contexts of what does and does not work, of what does and does not feel right, and of what does and does not support one being one’s best. In the case of attachment, that awareness flows from a likely highly subconscious, inchoate, visceral appreciation of the coupled roles of beauty and functional fitness. As Christopher Alexander observes:

Things that are good have a certain kind of structure. You can’t get that structure except dynamically. Period. In nature you’ve got continuous very-small-feedback-loop adaptation going on, which is why things get to be harmonious. That’s why they have the qualities that we value. If it wasn’t for the time dimension, it wouldn’t happen. . . . You want to be able to mess around with it and progressively change it to bring it into an adapted state. . . . This kind of adaptation is a continuous process of gradually taking care. (Brand, 1994, p. 21)

Attachment Feeds Reasonableness: A Virtuous Spiral

At a global level, we have places that remain interesting and have been sustained over centuries through care—and providence. New Orleans, Amsterdam, and Venice readily come to mind, and extraordinary measures have been and probably will continue to be taken to maintain each for centuries into the future. (Whether the extent of protective measures taken or proposed is environmentally wise is another issue, not argued here.)

American planners always take inspiration from Europe’s great cities and such urban wonders as the Piazza San Marco in Venice, but they study the look, never the process. . . . Venice is a monument to a dynamic process, not to great planning. . . . The architectural harmony of the Piazza San Marco was an accident. It was built over centuries by people who were constantly worried about whether they had enough money. The Piazza San Marco was not planned by anyone. . . . Each doge made an addition that respected the one that came before. That is the essence of good urban design—respect for what came before (Brand, 1994, p. 78).

As Basu and Kaplan (Chapter 1) point out, respect for others, in this case for predecessors and their customs and traditions, is a common endeavor we revere and pursue in seeking to act meaningfully. Virtuous cycles such as those that contributed to Venice’s survival can result from attachment. Landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures that respect and acknowledge—no matter how formally—antecedent contexts and practices foster further meaningful actions, leading to continuing small experiments, many of which deepen attachment and nurture reasonableness that benefits both the present and the future. Vernacular architects do not reinvent the wheel for the sake of being innovative; they focus their scant resources on being creative with the new challenges facing them. As is the case with favorite blue jeans (de Botton, 2006, p. 183):

The architects who benefit us most may be those generous enough to lay aside their claims to genius in order to devote themselves to assembling graceful but predominantly unoriginal boxes. Architecture should have the confidence and the kindness to be a little boring. We delight in complexity to which genius has lent an appearance of simplicity. . . . An architect intent on being different may in the end prove as troubling as an over-imaginative pilot or doctor.

Secret to Attachment: Age and Adaptivity

When asked what makes a building come to be loved (and therefore sustained), Brand (1994, 23) found that people universally voice a one-word answer: age. Actually, Brand eventually discovered that it is age plus adaptivity that creates a loving attachment to buildings. Adaptivity is neither predictable nor controllable, but designers can create the conditions for its expression (Figure 13.3). Of course, for buildings to have the freedom to adapt and lend themselves to long-term tinkering, they have to be durable enough to last.

Brand (1994, 71) distinguishes between buildings that are loved (i.e., to which people have an attachment) and those that are merely admired: “Admiration is from a distance and brief, while love is up close and cumulative. New buildings should be judged not just for what they are, but for what they are capable of becoming. Old buildings should get credit for how they played their options.” Brand (p. 186) suggests that a designer should think strategically, just as a chess player does: “Favor moves that increase options; shy from moves that end well but require cutting off choices; work from strong positions that have many adjoining strong positions.”

Adaptable is not the same as flexible. Decades of experimenting with modular units and walls have not led to such structures’ proving to be superior in accommodating future users and uses. With modularity, little learning from poor decisions likely occurs. Few benefits accrue from mere tweaking. Improvement in built environments and in our mental models results from conscientiously undertaken small experiments. Designing for adaptation demands deeper thinking and context-sensitive forethought, not just sequential, low-consequence, dissatisfied tinkering.

The ability to fail small, early, and often is the essence of redundancy-fueled natural “antifragility,” as Nassim Taleb, author of the celebrated The Black Swan (2007), now terms it. Antifragile systems are not the same as merely robust systems; they become stronger through responding to disorder and uncertainty. Embracing error, being open to the emerging whole in all its evolving intricacies, discovering things that don’t work, and trying things that might not work turn occupants into active learners rather than passive victims. By being effective in this way, occupants become midwives to successful and long-lasting designs. In this context, being effective means perpetually reappraising and adjusting—”being responsive to future hindsight,” as Brand (p. 188) puts it.

Routes to Attachment

The history of Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre, built in 1889 by Louis Sullivan and his partner Dankmar Adler, encapsulates many of the themes of this chapter, including the power and efficacy of narrative (R. Kaplan, Chapter 2)—the building’s story. The theater building was designed as one of the world’s first multiuse buildings (offices, theater, hotel), suggesting that it was—from the outset—an adaptive building (echoing, logically, from Sullivan’s form following function). Its sheer size worked to its favor when the theater closed during World War II, and the structure was turned into military barracks, complete with the former stage as a bowling alley (Henning, 2008). After the war, demolition discussions were set aside because of cost.

Restoration efforts through the years met with varied but continuing successes, and the theater is today the permanent home of the Joffrey Ballet as well as host to a variety of concerts, performances, and Broadway musicals. Time worked its magic. Shortly before his death in 1959, Frank Lloyd Wright said to a group of potential benefactors the words integral to an aesthetic of care: “Be kind to this theater and it will be kind to you.” Reasonable people support those environments that enable them to act reasonably.

A truly great structure, as is the case with a truly great wine, invites attachment through its ability to reveal itself in new ways. A man who has lived in a Frank Lloyd Wright–designed home (the Reisley House, in Pleasantville, New York) for nearly sixty years says (Rubin, 2009, p. 1):

We never really thought of it in terms of America’s architectural history. It was our family home and it has been for nearly 60 years. But I feel more like a steward of this house as time goes on. When I had been living here about 20 years I realized that every day I had noticed something new. Of course, bad things happened, like in any home, but every day I have noticed something new and beautiful about it.

While enjoyment might be the primary reason for people to become attached to newly acquired products, memories—not surprisingly—become the primary reason for attachment when people have owned products for a long time. This suggests that designers should produce not only products that evoke initial sensory and aesthetic pleasure but also ones that over time facilitate the formation of associations among products, people, and places or events. The incidence and depth of memory formation is enhanced by designing products that will be used in a social context and that encourage interactions among people, bringing out the best in people.

Ryan and Buxton (Chapter 11) explain that the associations of local residents with small community-developed green spaces spread beyond recreational use. Residents—even those who do not regularly enter the spaces—spend more time on the sidewalk in front of these spaces, engage in conversations with neighbors and friends near them, and view the spaces from their cars.

Buildings’ narratives create attachment by revealing, and reveling in, history. When my siblings and I had all left home, our parents built a new smaller house on a portion of our original lot. To fit the house in, builders had to remove a shagbark hickory. My parents then made the unusual move of having the wood from the tree kiln-dried and used it to panel the den that occupied the very location where the hickory had grown. This story has stayed with the house, even with its new owners. Stories feed attachment.

Detachment Breeds Pathology and Lack of Meaningful Action or Sense of Purpose

When buildings tell the wrong kind of stories (or, perhaps worse, no stories), they can exacerbate our indifference and neglectful attitude toward the structures themselves (Saito, 2007). An exemplar is the broken windows theory for reversing a crime epidemic: “If a window is broken and left unrepaired, people walking by will conclude that no one cares and no one is in charge. Soon, more windows will be broken and the sense of anarchy will spread from the building to the street” (Gladwell, 2000, 141).

The term “solastalgia,” Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht’s (2005) neologism, combines Latin solacium (“comfort”) with Greek -algia (“pain”) to describe a feeling of despair when one’s home environment changes. Solastalgia captures the notion of homesickness that one experiences while still being at home (Zimmer, 2011).

Through his studies of rural Australians upended by local coal mining, Albrecht realized that “place pathology,” as one philosopher has called it, is not limited to immigrants. Residents can feel powerless, like victims of an injustice. They become anxious, unsettled, despairing, helpless, depressed—just as if they had been forcibly removed from their homeland. Only they hadn’t; their valley changed around them.

Similarly, solastalgia is what happens to many elderly who wish, but cannot afford, to move when their neighborhoods radically change socioeconomically, racially, ethnically, or culturally. As their social networks fray and then collapse, their detachment from connections leads to their decreasing participation in the life of the city and soon to their no longer taking care of their neighborhoods, their parks, their streets, their homes, and eventually themselves. They decline well below a point of believing that they could make any difference. Mortality risk increases as people in extreme social isolation age and do not have friends nearby to give help, check up on them, ensure that they maintain a healthy lifestyle, identify acute symptoms, or advise that they really need to see a doctor.

In a nod to what is now termed “solastalgia,” several decades ago Tony Hiss (1991, p. 68) explained:

When we change the places around us, we each of us at the same time undergo changes inside. When we talk about the benefits of design, we’re talking about two things at once—what it does to us and what it does for us; architecture does much of its work by working within people.

After all, Winston Churchill famously remarked, “We make our buildings, and afterwards, they make us” (Brand, p. 3).

Being Planned Upon

Designers who believe they know what is best for clients and users can undermine users’ sense of competency and meaningfulness and derail the prospects that users would ever become attached to their creations. The saga of the Modernist movement offers numerous examples of planning upon others, perhaps most notably by one of its most famous practitioners. Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation apartment complex in Marseilles failed in part because the childless Le Corbusier provided no places where children could escape parents and vice versa. At some point, those living in his creations took meaningful action to reclaim their residences from the tyranny of the designer. Factory workers living in Le Corbusier–designed apartment buildings commissioned by a French industrialist reacted to being planned upon by using flowered wallpaper, pitched roofs, shutters, picket fences, and lawn gnomes to adapt their settings to their needs. These were small experiments that they could get away with and that created a foundation for housing they could become attached to.

S. Kaplan (Chapter 3) describes experts’ “hardening of the categories”: their tendency to define a problem’s solution set too decisively and perhaps too early. Le Corbusier—in many ways a prototypal expert—seems to have frequently designed structures as superb answers to not quite the right questions.

As Alain de Botton (2006) observed, we ultimately do not respect structures that merely keep us dry and warm—those merely aligned to minimal fitness needs and passable aesthetic preferences, those in the lower-left quadrant of the attachment matrix. In adapting their circumstances to their mental models of what could be and how to get there, the French factory workers took small steps and acted meaningfully and effectively to become their best selves.

Ginsburg (Chapter 9), in discussing the Education Justice Project at the Danville Correctional Center in Illinois, showed how the incarcerated men, too, taught themselves how to more effectively deal with imposed constraints and challenges—in their case of long-term incarceration. They were able to overcome their diverse and complex specific backgrounds by conducting small experiments using their shared mental models of what could be. Thus, they rose above their individual and collective short- and long-term circumstances of being planned upon and feeling hemmed in by limited horizons.

Examining sustainability through the lens of attachment highlights an important challenge regarding designers’ collaborating with intended users (see Grese, Chapter 19). Just who are the intended users or “the public” when, in the gestalt of sustainability, the affected public are both those about to inhabit the created landscape, space, city, or structure as well as users thirty or fifty years from now? We need to train planners and designers to nudge the public to realize that in a sustainable world, the current designer-public team must serve as proxies for the needs of those yet unborn who will also inhabit these designs.

Interactivity That Drives Meaningful Action

Victorian-era British art critic John Ruskin said (de Botton, 2006, p. 62) that we seek two things of our buildings: to shelter us and to speak to us. When the architecture speaks a language that the users do not hear or respect, either structures get modified or users decide to start over through demolition or moving elsewhere. If we do not intend to stay in a residence long, we either do not try to listen to the language the structure speaks or we ignore it. Either way, we are unlikely to undertake modifications that could satisfy our needs. The nature of modern buildings can often seem to conspire against taking meaningful action to align them more closely with our needs. All-season thermal comfort of inhabitants too often takes a backseat to mechanical engineers’ ideas of proper building performance (e.g., windows that cannot be opened). Such buildings speak a loud and clear language of structural disrespect, of a distrust of the workers themselves. The feelings quickly become mutual, extending to designers along with their structures.

The human-building language that is heard is fundamental to reasonable people becoming effective in taking action to (re)make their environment to conform to their needs. As de Botton (2006, p. 72) noted:

What works of design and architecture talk to us about is the kind of life that would most appropriately unfold within and around them. They tell us of certain moods that they seek to encourage and sustain to their inhabitants. . . . They . . . hold out an invitation for us to be specific sorts of people. They speak of visions of happiness. . . . A feeling of beauty is a sign that we have come upon a material articulation of certain of our ideas of a good life. . . . The notion of buildings that speak helps us to place at the very center of our architectural conundrums the question of the values we want to live by—rather than merely how we want things to look. . . . Architecture can arrest transient and timid inclinations, amplify and solidify them, and thereby grant us more permanent access to a range of emotional textures which we might otherwise have experienced only accidentally and occasionally.

Building 20 was a 250,000-square-foot World War II–era timber frame structure designed in a single afternoon for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s efforts to develop radar for the war effort. The building is legendary for having been one of the most creative spaces in the world. Its vertical layout with small floors created the proximity that forced diverse scientists to interact. Longevity per se was never a goal for the building. It was designed to last only a few years, as was so much of the Manhattan Project–era infrastructure in towns such as Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. Because of the sense of impermanence, workers felt free to improvise, to manipulate the structure to fit their needs. No one really watched or asked questions or requested permission as scientists bolted equipment to the roof, knocked down walls, or cut holes through several floors to accommodate a cylinder three-stories tall. Such behavior successfully functioned over the decades only because of the inhabitants’ sense of respect for the structure—they did their modifications responsibly. This flexibility, this interactivity between user and structure, nurtured the temporary early 1940s’ building all the way to its ultimate demolition in 1998. As Molloy (2013) noted, á la Churchill, “[The scientists] improved the building and the building improved them.”

In introducing the attachment matrix, I discussed how the relationship between users and built environments can, under strong attachment, have spousal-like dimensions that involve trust, respect, and a shared language. The Building 20 workers knew when seeking approvals for modifications would be viewed as annoying and when that would be prudent, just as spouses develop a sense of such interactive behavior, spoken and unspoken. Building 20 communicated to its workers when it was okay to modify it, reassuring them subliminally that this was what it was there for.

While we do create and alter environments to better meet our needs, we also sometimes resist all change because we find the status quo effectively meeting those needs. Numerous historic neighborhoods, landscapes, and structures have been saved from demolition or severe alteration by the resolve of people taking effective action to freeze in time that to which they are attached. Their actions likely involved problem solving, experimentation, teamwork, listening, and sharing to not only make a difference and bring out their best but also to contribute to updating and refining their mental models. In growing older, we become more skilled at recognizing that pursuit or protection of the shiny and the merely functional is no longer sufficient cause for action. We pick our battles more wisely.

Editors’ Comment: Embracing error allows for making small experiments.

Just as Bradley and Cooper (Chapter 12) discovered owners of small forests becoming emboldened to more deeply explore their holdings, Brand (1994, p. 209) points out that as we gain experience and wisdom, we become more reasonable by adjusting our environment in a way that is always future-responsible—open to the emerging whole, hastening a richly mature intricacy. The process embraces error; it is eager to find things that don’t work and to try things that might not work. By failing small, early, and often, it can succeed long and large. And it turns occupants into active learners and shapers rather than passive victims. Loved buildings are the ones that work well, that suit the people in them, and that show age and history. All it takes is keeping most everything that works, most everything that is enjoyed, and much of what doesn’t get in the way and helping the rest evolve.

Reasonable Behavior, Attachment, and Sustainability

The attachment matrix can help us translate knowledge and experience into effective action. Environments that nurture attachment are more likely to support reasonableness. Environments positioned in the other corners of the matrix can be shifted toward attachment by imbuing them with greater functionality and/or aesthetic quality. Once in the attachment quadrant, sustainability becomes a stewardship-lubricated ride, not an uphill struggle. Apple has most profitably married the highly functional with the beautiful to form uniquely strong customer bonds. Creating better functional fitness in those products that are merely engaging (the shiny ones) may aid their matriculation to attachment. Consider a sterile but elegant bank lobby that is repurposed as a restaurant, complete with banquet room or wine cellar in the old vault. While delighting new users, such conversions also save on energy, materials, and landfill space.

We have seen that age and adaptivity undergird landscapes, spaces, cities, and structures to which we become attached. Attachment is also strengthened by environments that, among factors common to other chapters in this volume,

Editors’ Comment: The environments described by Petrich evoke and extend individuals’ mental models and cultural perception about place.

- have stories behind their provenance,

- set and trigger social memories, and

- interactively promote exploration and experimentation among users and other stakeholders.

Our mental models reflect our attachment, helping us evaluate the status quo and serving to help us identify environments that might be more supportive. These mental models help us assess how we could beneficially modify such environments. They can give us a directed sense of purpose and help us achieve reasonableness (Basu, Chapter 6). We rely, knowingly or not, on our mental models of attachment to feel fairly confident that chosen tinkering and puzzle solving might be effective as we undertake actions that we believe will be meaningful in creating supportive environments. Together, the three RPM domains help establish contexts for our being most reasonable and, through attachment, simultaneously contribute to a more sustainable world.

People behaving reasonably and confidently are more likely to participate with others of like mind in trying out ideas in small, incremental steps to see what works and what comes up short (Basu & Kaplan, Chapter 1). Acting meaningfully to seek and protect emotionally valued places is a natural by-product of understanding the deeper relationships that connect us to special environments and to each other.

Acknowledgments

Figure 13.2 attributions: The four photographs are all from Flickr.com and used under the Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Creative Commons licence, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode.

- The White Castle restaurant (http://farm4.staticflickr.com/3800/8896795911_f9a40f74f4_b_d.jpg) is attributed to kennethkonica.

- The glass sink (http://www.flickr.com/photos/7986902@N02/3545295091/in/photolist-6phyHr-6tgvrk-6tCZE6-6tVpSN-6x35TM-6A26gA-6EnKgf-6LMrsa-6VLYZV-6Wu1hS-78g7Q3-7nyN4a-81y7Ls-8NBYSq-9CW6cv-7z25B2-cckHhG-bBe4Ez-cwkk3u-7RYsQg-8SqkJk-dn3YcT-bfvirz-7ybbgi-7PGAPk-7PKNad-8NKZcV-aXLKJe-aXLJS2-aXLJpK-aXLKfF-aXLHiX-7TA2q2-boXA28-82T9gj-8q7gYR-anKgXM-bBkiP8-9BtASe-bq6pRY-bq6pPS-drZ6fi-bbpVTR-aCBcP1-e4AK1a-chgked-chgmoj-chgm35-chgkoN-chgkRU-chgkBm) is attributed to J. Trent Adams.

- The Airstream trailer (http://www.flickr.com/photos/galactic/515320008/sizes/l/in/photostream/) is attributed to bluelizardworld.

- The blue jeans photograph (http://www.flickr.com/photos/70571033@N00/198419430/in/photolist-iwXbE-j8BsE-kCzsq-meZkM-nrN9E-o2NAN-oJ7M6-qPHf9-tqpfs-turiz-xkhp6-yuyq1-yKfVX-zepgx-zMnUC-BvJDw-CpLfC-CUbmy-DvQDU-E4Xj6-GiBvx-Gsp2R-H41t4-JEU5P-JQraP-MiLhs-Mjj2F-MzXqb-2awE4U-2rR1CA-2vVW1R-2wpQyq-2DooxD-2FSkfB-35VKEV-3bAbeW-3yowfE-3JWadf-3VxxPm-3W3Gea-3X27QQ-44c79m-4kpnsx-4oaQvi-4od1nV-4oLKeb-4oYtu3–4qRFRt-4sVekH-4sVf8e-4sZbd1) is attributed to lifecreations.

References

- Albrecht, G. (2005). Solastalgia, a new concept in human health and identity. Philosophy Activism Nature, 3, 41–44.

- Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brand, S. (1994). How buildings learn: What happens after they’re built. New York: Penguin.

- Chapman, J. A. (2006). Emotional attachment: Developing lasting relationship with our belongings. Waste Management World. Retrieved from http://www.waste-management-world.com/index/display/article-display/273720/articles/waste-management-world/volume-7/issue-5/recycling-special/emotional-attachment-developing-lasting-relationships-with-our-belongings.html.

- de Botton, A. (2006). The architecture of happiness. New York: Pantheon.

- Gladwell, M. (2000). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Heathcote, E. (2008, July 10–11). The irreverent imperfectionist. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/83d9d9c4-4ee0-11dd-ba7c-000077b07658.html#axzz2kaDkWEFK.

- Heathcote, E. (2011, January 9). How to build heritage: What factors explain how a building’s design becomes rooted in a particular landscape? Financial Times Weekend, House & Home, p. 1. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/96643ce8-4e99-11dd-ba7c-000077b07658.html#axzz2nxhzV6W7.

- Henning, J. (2008, Sept. 6–7). Form follows function, elegantly. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB122064771323104933.

- Hiss, T. (1991, April). You are what you see. Metropolitan Home, p. 68.

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (2009). Creating a larger role for environmental psychology: The Reasonable Person Model as an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 329–339.

- Molloy, J. C. (2013, April 3). Can architecture make us more creative? ArchDaily. Retrieved from http://archdaily.com/353496.

- Nassauer, J. I. (2007). Cultural sustainability: Aligning aesthetics and ecology. In A. Carlson & S. Lintott (Eds.), Nature, aesthetics, and environmentalism: From beauty to duty (pp. 363–379). New York: Columbia University Press.

- O’Connor, J. (2004, October). Survey on actual service lives for North American buildings. Presented at Woodframe Housing Durability and Disaster Issues Conference, Las Vegas, Nevada.

- Richardson, L. S. (2002, Winter). Tasting rainbows: A look at the art and science of measuring emotional response, with a new concept for user research. DesignMind. Retrieved from [formerly http://designmind.frogdesign.com/articles/winter/tasting-rainbows.html].

- Richardson, L. S. (2007). The art and science of measuring emotion. Retrieved from www.m3design.com.

- Rubin, G. (2009, July 12). Designed for life: Buildings by the great men of architecture are still cherished as private residences. Financial Times Weekend, House & Home, p. 1.

- Saito, Y. (2007). The role of aesthetics in civic environmentalism. In A. Berleant & A. Carlson (Eds.), The aesthetics of human environments (pp. 203–218). Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview.

- Sheppard, S. R. J. (2001). Beyond visual resource management: Emerging theories of an ecological aesthetic and visible stewardship. In S. R. J. Sheppard & H. Harshaw (Eds.), Forest and landscapes: Linking ecology, sustainability (pp. 149–173). Wallingford, UK: IFRO Research Series, No. 6. CABI, CABI Publishing.

- Taleb, N. N. (2007). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable. New York: Random House.

- Thomas, L. (2005, November 10). The secret language of jeans. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/fashion/2005/11/the_secret_language_of_jeans.html.

- Zimmer, B. (2011, April 22). Eco-Speak: An Earth Day Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.visualthesaurus.com/cm/wordroutes/2828/.