Motivated Reasoning and Persuading Faculty Change in Teaching

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Many faculty members demonstrate unwavering resistance to adopting research-based instructional strategies. This phenomenon commonly fits with motivated reasoning, whereby a person feels threatened by persuasion to change, leading to overtly defensive and sometimes disruptive behaviors and refusal. Changing away from established practices may challenge one’s self-identity and values as an effective teacher and triggers arguments intended to invalidate research-based alternatives. Faculty who are motivated to reject consensus best practices may impede the implementation of these practices across entire departments or institutions. Motivated reasoning and its underlying cognitive processes are explained by self-determination theory, which leads to predictions of faculty behaviors and suggesting more effective persuasion approaches by educational developers. Change conversations need to preserve the basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (especially within affinity groups) in order to succeed. Importantly, persuasive argumentation with data or authoritative viewpoints, which succeeds with many faculty who electively attend educational-development programs, will predictably have limited success with faculty who respond with motivated reasoning.

Keywords: motivated reasoning, faculty change, faculty development, self-determination theory

Introduction

Many authors (e.g., Bok, 2006; Halpern & Hakel, 2003; Tagg, 2012) comment on the lagging adoption of research-based instructional strategies (RBIS; Henderson et al., 2012), particularly in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields that benefit from decades of discipline-based education research (Lund & Stains, 2015; National Research Council, 2012; Seymour, 2001; Wieman & Gilbert, 2015). Implementing RBIS practices commonly replaces traditional classroom lectures with carefully designed active-learning strategies based on research consensus (Freeman et al., 2014). This consensus is sufficiently strong so that Nobel Laureate Carl Wieman (2014) stated that “any college or university that is teaching its STEM courses by traditional lectures is providing an inferior education to its students” ( p. 8320).

Slow implementation of widely disseminated RBIS invokes assessments of adoption barriers (e.g., Brownell & Tanner, 2012; Henderson et al., 2011; Henderson & Dancy, 2007; Nelson, 2010; Tagg, 2012). This issue is particularly important for educational developers who create RBIS-dissemination activities with the expectation that faculty will adopt these practices and generate improved learning outcomes comparable to those reported in the research literature. From an implementation science perspective, however, there is a large gap between the dissemination of innovative teaching approaches and their incorporation into teaching practice with sufficient fidelity to improve learning (Smith & Stark, 2018).

Persuasion is the critical bridge of the dissemination-to-practice gap (Smith & Stark, 2018). Persuasion ideally proceeds whereby each piece of acquired information is weighed appropriately with existing information so that attitudes are updated like a running tally. A result is the assumption that faculty will adopt RBIS when presented with compelling data (Freeman et al., 2014) or authoritative endorsement (Wieman, 2014). However, this assumption is challenged by observations on the spreading of innovative ideas and methods (Rogers, 2003) and particularly in educational development programs where leading with innovation-supporting data was unfruitful (Andrews & Lemons, 2015; Wieman, 2017). People change attitudes (and behaviors) because they are persuaded that a different point of view is superior to the one they currently hold. It is rare that all evidence pertinent to a decision is unambiguously certain. The stronger the personal expectation that a preferred hypothesis is true, the greater the likelihood that a person will interpret ambiguous data as consistent with that desired hypothesis (Sarewitz, 2004; Trope & Liberman, 1996). Rather than simply ignoring data or choosing nonparticipation in change initiatives, a person may actively resist change efforts, as shown by sample quotes in Table 1.

|

Statements in Table 1 illustrate a refusal behavior called motivated reasoning. Motivated reasoning describes evaluating new information—data, logical arguments, credibility of information sources—to conform with existing values and perceptions of truth rather than forming an accurate, consensus-based belief (Kahan, 2014). The concept received considerable attention in the 1990s, following the foundational work of Kunda (1990), and gathered renewed attention in analyses of low public acceptance of scientific consensus regarding climate change (Hamilton, 2011; Kahan, 2014; Kraft et al., 2015) and of political polarization on many issues (Hart & Nisbet, 2012; Kahan, 2016; Taber & Lodge, 2006).

The purposes of this paper are to (a) help faculty developers recognize motivated reasoning; (b) explain the processes that constitute motivated reasoning; (c) propose a theoretical foundation from self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) to explain its cause; and (d) propose educational development strategies, requiring testing, that may attenuate this very resilient and commonly disruptive behavior. I posit that educational development workshops, seminars, learning communities, and consultations primarily attract people who seek reinforcement of teaching practices or who are open to learning better ways of teaching. Other individuals are unlikely to seek out these opportunities because they reject the discordance between their teaching beliefs and accepted practices or perceive unacceptable risks if they change, hence the adage that educational developers “preach to the choir.”

Nonetheless, the “non-choir” members may negatively impact dissemination and implementation of research-based pedagogy. First, developers encounter the non-choir at broadly focused or compulsory events such as departmental meetings, new-faculty orientation, and required trainings, where the resulting defensive arguments, such as in Table 1, disrupt or derail developers’ objectives. Second, faculty develop their teaching practices more through their own learning and teaching experiences along with peer interactions in the workplace than by formal development programs (Andrews et al., 2016; Hativa, 1997; Knight et al., 2006; Lund & Stains, 2015; Oleson & Hora, 2013; Smith & Stark, 2018; Stark & Smith, 2016). Faculty persuaded to use RBIS may, as a result, feel challenged by colleagues holding strong contrary views (Ginns et al., 2010), which erodes adoption or persistence with RBIS. Therefore, the likelihood, causes, and responses to motivated reasoning should be appreciated by both developers and faculty to support dissemination and implementation of RBIS.

Motivated Reasoning

Foundational Concepts and Key Examples

Motivated reasoning has not, based on literature review, been explicitly studied among higher-education faculty. Thus, essential concepts for understanding the phenomenon require transfer from research in psychology and political science. Importantly, this research documents a common human behavior without suggesting how to persuade those who exhibit this behavior. Therefore, this article explores alternative persuasion strategies rooted in understanding the underlying processes for motivated reasoning and a proposed theoretical explanation.

Early studies illustrate the classic features of motivated reasoning. Lord et al. (1979) told participants to read two articles on the deterrent efficacy of capital punishment and then evaluate whether the research supported either side of the death penalty debate. One article concluded that capital punishment deterred murder, whereas the other concluded that capital punishment was an antideterrent. The participants, both capital punishment proponents and opponents, rated how convincing each study was. Methodology and quality of the evidence were rated highly if the study confirmed the subject’s beliefs. Conversely, the article reporting disconfirming results was evaluated as unconvincing. In other words, opposite evaluations of the same research resulted from whether the study confirmed or disconfirmed the subject’s prior beliefs. During interviews, the participants focused on discrediting the methodology of the disconfirming study as the rational justification for discarding its conclusions. In addition, more effort was expended on criticizing the disconfirming paper than supporting the confirming one.

In another study, Kunda (1987) assigned female and male participants to read an adaptation of a peer-reviewed medical journal article concluding that women, but not men, who drank three or more cups of coffee per day for more than one year were at risk for painful precancerous breast cysts. When surveyed about the evidence and arguments in the paper, men accepted the conclusion, regardless of their caffeine consumption. Women who consumed fewer than three cups of coffee daily also accepted the link between caffeine consumption and the disease. However, women who consumed more caffeine were, as a group, less convinced by the study and identified perceived weaknesses in study design as the reason for discounting the validity of the argument.

In coining the term motivated reasoning, Kunda (1990) tested the thesis that when encountering a persuasive argument, individuals make reasoned rational judgments, but in doing so, they are biased to satisfy a goal based in their needs, hopes, beliefs, and values and to defend that goal. In the context of the faculty statements in Table 1, motivated reasoning is revealed by a perceived threat to individual values and identity as a teacher. To accept evidence favoring alternative pedagogical practices would mean acknowledging that one is not a highly effective teacher or, even, that one’s past practices have been discriminatory or otherwise harmful (Nelson, 2010).

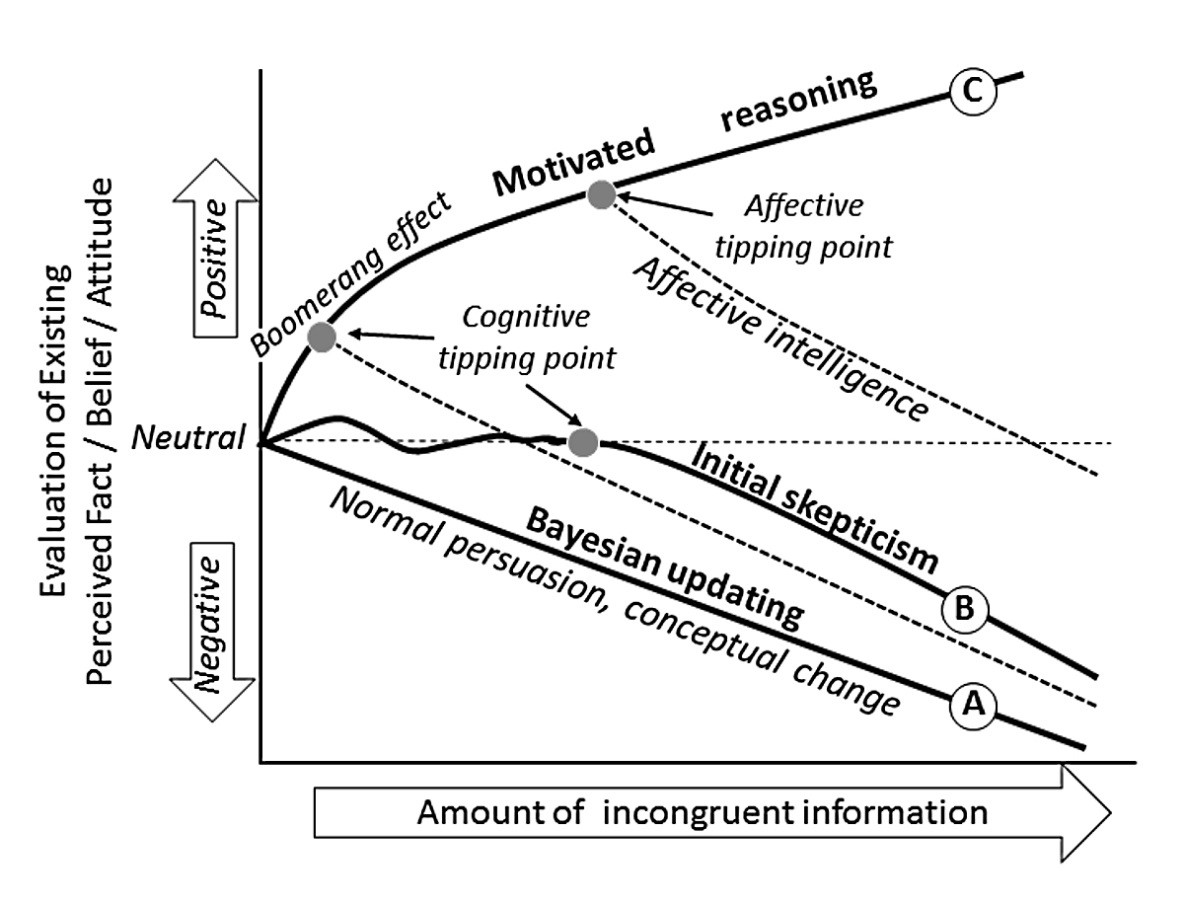

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram of Attitude Change as a Consequence of Receiving Increasing Amounts of Information That Is Incongruent with an Existing Perceived Fact, Belief, and/or Attitude Note. Path A illustrates continual Bayesian updating as the new information is accepted and the previous state is increasingly viewed as incorrect (negative evaluation). Path B illustrates one possible expression of initial skepticism with little change from the previous state that then changes by Bayesian updating. Path C represents motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990) whereby the existing state paradoxically strengthens in the face of incongruent information. Although the argument attending the incongruent information was intended to generate a negative evaluation of the present state, there is a boomerang effect (Hart & Nisbet, 2012) whereby the evaluation becomes more positive. Dashed lines show potential transitions to Bayesian updating caused either by overwhelming anxiety in the face of increasing incongruency (affective tipping point of Redlawsk et al., 2010) or by a cognitive tipping point, also seen in path B, caused by deeper processing of the new information that elaborates on testing the existing and alternative hypotheses. Cognitive tipping points are affected not only by the strength of persuasive argumentation but also, especially along path C, by reducing threats that diminish defensiveness and improve rational thought.

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram of Attitude Change as a Consequence of Receiving Increasing Amounts of Information That Is Incongruent with an Existing Perceived Fact, Belief, and/or Attitude Note. Path A illustrates continual Bayesian updating as the new information is accepted and the previous state is increasingly viewed as incorrect (negative evaluation). Path B illustrates one possible expression of initial skepticism with little change from the previous state that then changes by Bayesian updating. Path C represents motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990) whereby the existing state paradoxically strengthens in the face of incongruent information. Although the argument attending the incongruent information was intended to generate a negative evaluation of the present state, there is a boomerang effect (Hart & Nisbet, 2012) whereby the evaluation becomes more positive. Dashed lines show potential transitions to Bayesian updating caused either by overwhelming anxiety in the face of increasing incongruency (affective tipping point of Redlawsk et al., 2010) or by a cognitive tipping point, also seen in path B, caused by deeper processing of the new information that elaborates on testing the existing and alternative hypotheses. Cognitive tipping points are affected not only by the strength of persuasive argumentation but also, especially along path C, by reducing threats that diminish defensiveness and improve rational thought.Why is a person not persuaded to change their mind when presented with compelling evidence? Figure 1 summarizes alternative reactions to challenges to existing belief or understanding. Bayesian updating is the traditional method of analyzing rational thought involving the evaluation of new information. One has a prior factual belief and then encounters new, contrary evidence. Evaluating the evidence leads to a revised, updated belief that weakens the original belief (Figure 1, path A). If, however, that new evidence is evaluated based on prior belief or the perceived negative consequences of believing the new evidence, then an external factor intervenes and the weighting of the new evidence is biased rather than set by the strength of the evidence alone. This non-Bayesian updating is motivated reasoning (Figure 1, path C; Kahan, 2016). Notably, this phenomenon differs from well-known confirmation bias, which is the tendency to unwittingly see what one wants to see, to focus on information that directly supports one’s favored hypotheses (Nickerson, 1998). With confirmation bias there is a tendency to ignore contrary information, whereas motivated reasoning includes purposeful, defensive activity to discredit contrary evidence (Kunda, 1990; Table 1).

For example, a faculty member may believe that lecturing is the most effective mode for STEM instruction. New, incongruent evidence (e.g., the meta-analysis by Freeman et al., 2014) is presented, and the recipient is asked to accept that structured active learning is a superior instructional practice. However, the prior belief that lecturing is superior along with incongruent evidence that threatens one’s values as a teacher can lead to rejecting the benefits of active learning and strengthen perceptions of the importance of lecture instruction.

Notably, motivated reasoning differs from harboring misconceptions, which negates the effectiveness of conceptual change interventions. Conceptual change describes the rejection of prior understanding in favor of a new mental model (Hynd, 2001) and resembles path A in Figure 1. Refutation through oral or written discourse is the most researched conceptual change strategy (Hynd, 2001; Kendeou et al., 2014; Kowalski & Taylor, 2011; Sinatra & Broughton, 2011). Refutation induces cognitive dissonance by drawing simultaneous attention to the consensus explanation and the shortcomings of previously held misconceptions to trigger formation of a new mental model to resolve that dissonance. However, with motivated reasoning, counterattitudinal information engages attention for the purpose of dismissal and counterargument to preserve current beliefs as a resolution to dissonance rather than willingness to accept the consensus alternative. Refutational tones, such as Wieman’s (2014) statement, arouse defensiveness and argument using motivated reasoning rather than fostering discard of existing beliefs to accept another concept, even if the person clearly understands that concept (cf. Sinatra et al., 2003).

Along all paths shown in Figure 1, people rationally justify their decision, although their memory search may only retrieve beliefs and rules that support a desired conclusion (Kunda & Sinclair, 1999). Consider quote 3 in Table 1, in which the speaker does not recall alternative evidence that they have recently seen. Motivated reasoning includes biased selection of rules for evaluating evidence, which includes attacking the methods by which the challenged evidence was acquired (e.g., Kunda, 1987; Lord et al., 1979). Motivated reasoning is a natural reasoning adaptation suited to promote existing self-interest, and it is not a cognitive deficiency (Kahan, 2013; Lord et al., 1979).

The emotional nature of many comments instigated by motivated reasoning as shown in Table 1 invites uncritical comparison to dual-process theories in psychology popularized by Kahneman (2013). Specifically, motivated reasoning may be inappropriately attributed to the “thinking fast” System 1 processes that yield rapid, intuitive, and default heuristic responses that do not require working memory. However, motivated reasoning responses such as those in Table 1 and in the Lord et al. (1979) and Kunda (1987) studies demonstrate argumentation that requires the deliberate, logical thought of the “thinking slow” System 2.

Motivated reasoning focuses on argumentative justification of beliefs or actions. So, contradictory information is not evaluated for validity but is seen from the start as something to rebut. The rebuttal focus means that educational developers may not succeed when arguing with data or authoritative sources. Instead, a so-called boomerang effect occurs (Hart & Nisbet, 2012; Figure 1), in which a message produces the opposite effect from what was intended (e.g., Table 1, quotes 1 and 2). If eventually persuaded of the validity of new information, people may then deny the implications, as seen when instructors accept the validity of data in the context of a published study but deny its relevancy to their teaching (e.g., Table 1, quotes 1 and 5).

Motivated reasoning may include activation of stereotypes and misattributions that would not otherwise be used in judgment (Kunda & Sinclair, 1999). Some faculty invoke stereotypes about students of particular socioeconomic or racial/ethnic groups or generalize about “today's students” being “less prepared and lazy” as the motivations to defend their way of teaching (perhaps evidenced in Table 1, quotes 1 and 2). Kahan (2014) added the observation that researchers are only considered experts if they uphold the person’s existing belief. Therefore, even the credibility of an advocate for an alternative viewpoint can be disputed by motivated reasoning (e.g., reference to “so-called experts” in Table 1, quote 4).

Motivated reasoning is an act of refusal, an overtly defensive stance against new information, regardless of its logical strength (Munro & Stansbury, 2009). Refusal should not be confused with resistance, which may include healthy skepticism toward the new evidence but with openness to a critical evaluation that may lead to acceptance through deep processing of both previously held and newly presented knowledge (Figure 1, path B). Resistant thinking is more accessible to traditional forms of persuasion with evidence, whereas refusal leads to debating evidence that threatens current values or beliefs. This is the difference between someone who is skeptical of evidence for changing teaching practice versus someone who denies and argues against that evidence.

Component Processes of Motivated Reasoning

The largely descriptive literature on motivated reasoning provides little understanding of the reasoning processes that are important for change agent persuasion strategies. The processes underlying motivated reasoning among faculty are potentially found in other concepts regarding the psychology of change and persuasion (Table 2). Most of this research makes little or no explicit reference to motivated reasoning but adds to the basis for seeking a theoretical explanation for the behavior. The concepts summarized below explain the pathways in Figure 1 when faculty consider new knowledge about teaching and learning.

| Concept | Explanation | Expression in motivated reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Theory of basic values | Each individual holds a hierarchically ranked set of universal values | Motivated reasoning favored by prioritization of self-enhancement and conservation values |

| Homogeneous social networks | Attitudes strengthened, less susceptible to persuasion within valued social groups | Attitudes conform to those of respected colleagues and friends |

| Identity-protective reasoning | Reasoning with the norms of a professional domain may not extend beyond that domain | Critical reasoning is not applied uniformly to hypothesis testing if one hypothesis threatens identity |

| Regulatory fit theory | Pursuit of a goal is sustained when an individual’s promotion or prevention regulatory orientation fits the means to attain the goal | When considering a proposed goal that is contrary to belief, a prevention orientation is most likely, if there is any engagement at all |

| Cognitive closure | Desire to acquire definite, confident knowledge quickly and permanently | One will more readily find reason to preserve an existing attitude than to reopen to consideration of information that challenges that attitude |

| Affective tipping point | Persistent information delivery that is incongruent with beliefs causes anxiety that eventually triggers an accuracy goal | Motivated reasoning may eventually lead to an affective intelligence change in attitude |

| Goal-directed hypothesis testing | Asymmetric thresholds for accepting/rejecting favored or alternative hypotheses leads to rational but biased hypothesis testing | Changing attitudes through scrutiny of evidence is challenged by low threshold to accept favored hypothesis and a low threshold to reject an alternative |

Expression of Values

Values are desirable goals that motivate actions and attitudes toward newly received information (Schwartz, 2012) and are foundational to motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990). When received information is contrary to a desired value-based goal, an individual may simply avoid it (confirmation bias) or may, using motivated reasoning, evaluate it as bad and illegitimate.

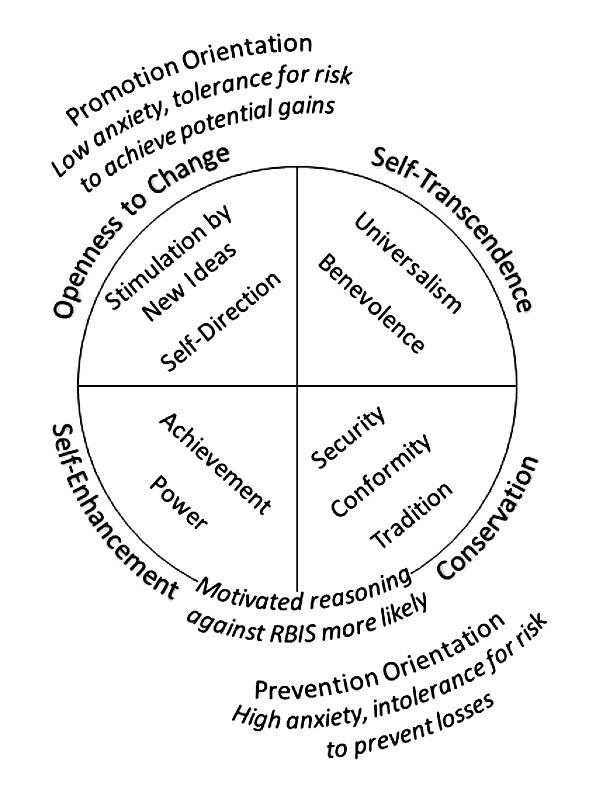

Strongest value conflict arises along two conceptual axes (Figure 2; Schwartz, 2012). Conservation values contrast with openness to change values, and self-transcendence values are incongruent with self-enhancement values. Self-enhancement and conservation values cause anxiety and motivate actions to protect against threat by preventing losses that are recognized as motivated reasoning (Figure 2). In contrast, openness to change and self-transcendence are relatively free from anxiety and motivate actions of self-expansion and growth.

Figure 2. Connecting Primary Values and Regulatory FitNote. Conservation or self-enhancement primary values (Schwartz, 2012) are more likely to activate defensiveness against persuasion to change teaching approaches in comparison to openness to change and self-transcendence values. This defensiveness may be expressed as motivated reasoning. Regulatory fit (Higgins, 2000) may relate to these values, with promotion orientation more likely related to openness to change, and perhaps self-transcendence, with prevention orientation more strongly related to conservation, and possibly self-enhancement, values.

Figure 2. Connecting Primary Values and Regulatory FitNote. Conservation or self-enhancement primary values (Schwartz, 2012) are more likely to activate defensiveness against persuasion to change teaching approaches in comparison to openness to change and self-transcendence values. This defensiveness may be expressed as motivated reasoning. Regulatory fit (Higgins, 2000) may relate to these values, with promotion orientation more likely related to openness to change, and perhaps self-transcendence, with prevention orientation more strongly related to conservation, and possibly self-enhancement, values.Although not explicitly tested, motivated reasoning behaviors among faculty resisting change are most readily explained (cf., Epley & Gilovich, 2016) by their prioritizing security, conforming, and achievement (Figure 2), where achievement is viewed in terms of the perception that academia places higher value on research than teaching. Nonetheless, Schwartz’s surveys across cultures show highest priorities for benevolence, universalism, and self-direction values. Therefore, endorsement of RBIS would likely benefit from efforts to enhance individuals’ priority for these more broadly perceived values, which would prioritize egalitarian learner outcomes (e.g., Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Haak et al., 2011) through self-directed exploration and incorporation of new teaching practices.

Preserving Affinity Groups and Identity

Attitudes are strengthened and less susceptible to persuasion when we are surrounded by people who hold views congruent to our own. If a faculty member affiliates with colleagues who share conservation values about teaching, then motivated reasoning to refuse RBIS is more likely. Research on motivated reasoning in debates surrounding controversial social and political issues draws attention to the importance of formal or informal membership in a group that shares beliefs and values (Kahan, 2013, 2014). Motivated reasoning preserves affinity to those from whom a person draws emotional or material support, which may include faculty colleagues who share a belief in the efficacy of teacher-centered instruction and deny the RBIS evidence.

Conversely, attitudes are weakened and vulnerable to change when a social network includes people who are viewed as important but who hold different views (Levitan & Visser, 2009). If some faculty adopt RBIS, then the infusion of alternative ideas into a socially important departmental network may increase the possibility of persuasion, especially if departmental pro-RBIS opinion leaders (Andrews et al., 2016; Rogers, 2003; Smith & Stark, 2018) are otherwise viewed as important and respected because of seniority or other accomplishments, such as in research. Therefore, social networks unique to each department or individual may strongly influence change in teaching beliefs and practices.

Resistance to teaching changes may also relate to protection of a professional identity as a disciplinary expert. For comparison, Kahan et al. (2016) found different applications of motivated reasoning among judges, lawyers, law students, and the general public when presented case information about polarizing political issues. Judges and lawyers did not exhibit motivated reasoning toward one side of these cases, whereas the law students and the general public did. However, when presented information unrelated to legal judgments, motivated reasoning was evident across all four groups. The authors concluded that professional judgments are resistant to bias because of domain-specific, identity-protective reasoning, but people may pursue value-based refusal outside of that professional domain. Therefore, university faculty who are skilled in critical thinking within their disciplinary domain may still demonstrate motivated reasoning against adopting RBIS. Given limited professional background or identity as teachers (Brownell & Tanner, 2012; Herckis, 2018), they do not use their discipline-based judgment processes when evaluating best practices in teaching.

Maintaining Cognitive Closure

Persuasion to change teachers’ approaches depends on their cognitive-closure status regarding teaching. Cognitive closure (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996) is a desire to acquire definite, confident knowledge based both on urgency (a desire to reach closure on this state quickly) and permanence (the desire to maintain that knowledge without needing to reconsider it). Belief crystallization occurs when urgent seizing of knowledge ends, and the existing knowledge is permanently frozen as accepted fact. Once closure to an idea (e.g., RBIS) occurs, it is psychologically difficult to unfreeze and add relevant knowledge. People are more open to persuasion prior to crystallization, perhaps even with uncritical analysis of the evidence, because a persuasive argument hastens desired closure. However, once past the crystallization point, the same well-constructed arguments are met with motivated rebuttal and counterarguments intended to retain the permanence of closure.

From the cognitive closure standpoint, motivated reasoning is not an initial disposition but arises after crystallization is reached. Some faculty members may remain open longer to ideas related to their generally better rewarded disciplinary research than to their teaching. By contrast, these faculty seek closure on teaching approaches very early and resist unfreezing later on. This speaks to the potential efficacy of introducing information about RBIS in programs that prepare future and new faculty to satisfy a need for closure about teaching knowledge and skills early in their careers.

Closure is also driven by a desire to reduce ambivalence, that is, the extent to which a person holds both positive and negative views of a concept even though preferring only one (Clark et al., 2008). If there is high ambivalence, then an argument of any quality that supports the preferred view is judged as more persuasive because it quickly reduces ambivalence. At the same time, Clark et al. (2008) discovered that if current opinion is neither strongly positive nor negative (i.e., ambivalence is low), a person pays more attention to strong arguments, even if they are contrary to the slightly preferred view. Motivated reasoning against teaching change, therefore, is heightened by a high ambivalence belief for conserving current crystallized practice. Shifting a view about approaches to teaching may be more successful if ambivalence for this opinion is low. A teacher with low ambivalence opinions of traditional teaching methods may experience cognitive dissonance that generates further seizing, rather than rejection, of information when confronting a strong argument against those methods.

Selecting a Promotion or Prevention Orientation to Change

If a faculty member facing new information about RBIS feels that the status quo of their teaching approach is secure, then there is a choice between not risking change that may cause a loss and risking change to seek a potential gain above the current, stable situation. This choice is explained by regulatory fit theory as the distinction between a prevention and promotion orientation (Table 3; Cesario et al., 2008; Higgins, 2000; Molden & Higgins, 2005; Molden et al., 2008). The promotion-oriented teacher learning about RBIS tolerates risk and eagerly considers interventions that are pitched as likely to generate gains for their students and, hence, advance their image as a teacher. The prevention-oriented colleague responds vigilantly and skeptically to RBIS advocacy because of anxiety regarding risks to their comfortable status quo. Promotion versus prevention orientation may relate to values that foster open-mindedness and growth versus conservation (Figure 2).

| Orientation | Focus | Outcomes | Strategy | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion | Presence/absence of positive outcomes (hopes, aspirations) that nurture oneself or others; maximum standards for ideal growth | Gains (preferred) or nongains | Eager: Focus on hits with some tolerance of misses; willingness to consider all plausible hypotheses; persistence; openness to improvement feedback | Faculty member willing to take risks to seek a positive outcome for learners and enhance self-image as a teacher |

| Prevention | Presence/absence of negative outcomes (duties, obligations) that protect the security of oneself or others; minimum standards to avoid deficits | Loss or nonloss (preferred) | Vigilance: Low tolerance of misses (attention to avoiding mistakes); consider only most probable hypothesis; anxiety when things do not go well | Faculty member willing to work within their comfort zone to ensure that learner outcomes and self-image as a teacher do not deteriorate |

Relevant to educational development is the observation that people act to address prevention concerns before promotion concerns (Molden et al., 2008). Self-preservation and conservation values may, therefore, draw to an educational development program those teachers seeking to avoid the anxiety of increased student failures in their courses even if they deny the efficacy of RBIS. Tapping into this prevention orientation may motivate the elaborative processing of evidence that leads the teacher to modify teaching practices. Successful engagement with this faculty member may be more effective by trying to activate a prevention orientation even though the program was designed to foster an eager promotion orientation. Therefore, development efforts may benefit from incorporating both orientations. Focusing as Wieman (2014) does on reducing failure rates through use of RBIS may help with conservation, prevention-oriented faculty, whereas focusing on the very substantial average gains in conceptual mastery through use of RBIS, as Hake (1998) does, may help with open-to-change, promotion-oriented teachers.

Changing Thresholds for Accepting and Rejecting Hypotheses

Fundamentally, persuasion in faculty development asks people to test the hypothesis that a different instructional approach (e.g., RBIS) is better than what they experienced as learners, practice as instructors, or both (Oleson & Hora, 2013). A new hypothesis may conflict with one or more hypotheses that a person already holds as likely to be true.

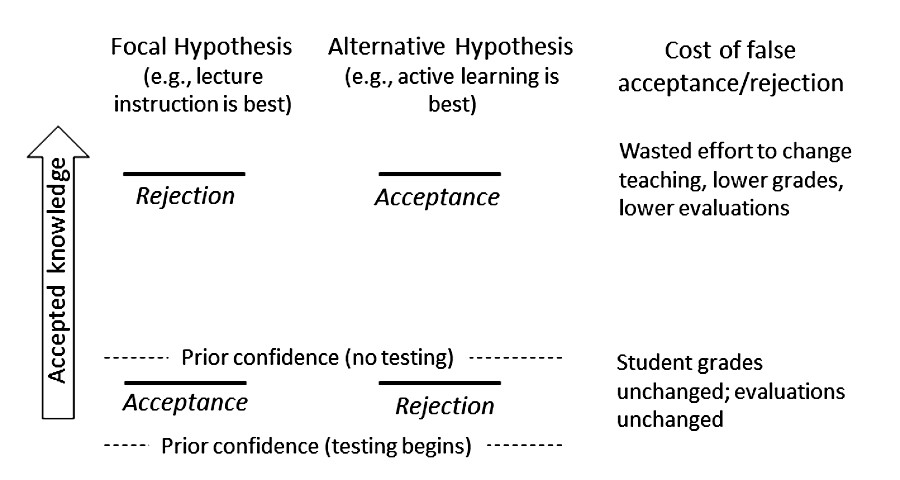

Hypothesis testing is driven by two confidence thresholds (Trope & Liberman, 1996): an acceptance threshold that the hypothesis is likely true and a rejection threshold that it is likely false (Figure 3). Errors, with accompanying cognitive, emotional, and perhaps material costs occur when falsely rejecting a correct hypothesis or falsely accepting an incorrect hypothesis. The acceptance threshold for a hypothesis is lower when the false-acceptance cost is low. Likewise, if the false-rejection cost is low, then the rejection threshold is also low. Prior confidence—which describes the person’s faith in the hypothesis based on prior experience—dictates that testing only occurs if the minimum thresholds of both acceptance and rejection are not yet met (Figure 3), implying a feeling of uncertainty that would benefit from closure (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996). Hypothesis testing persists only until a threshold is reached. An individual’s assessed costs of false acceptance and false rejection are almost always different, which sets different thresholds for either accepting or rejecting a hypothesis (Trope & Liberman, 1996). A desirable focal hypothesis will likely have more lenient acceptance criteria and more stringent rejection criteria (Figure 3). Epley and Gilovich (2016) concluded that when considering a desirable hypothesis, a person will likely ask, “Can I believe this?” In contrast, when considering a proposition one would prefer not to be true, the tendency is to ask “Must I believe this?” In most cases, some evidence exists for even the weakest argument, to support the “Can I?” conclusion, and some contradictory evidence almost always exists for the strongest hypothesis, allowing easy dismissal by application of the “Must I?” standard. These contrasting evidentiary standards influence reasoning.

Figure 3. Applying Hypothesis Testing to Changes in TeachingNote. Hypothesis testing involves a rational bias that is associated with asymmetric thresholds for acceptance and rejection for competing hypotheses (Trope & Liberman, 1996 ). The diagram illustrates the testing of a preferred focal hypothesis of lecture as a superior teaching strategy alongside an alternative hypothesis stating the efficacy of active learning. Notice the asymmetric thresholds for accepting and rejecting each hypothesis. Hypothesis testing occurs only if the current confidence in accepted knowledge is below all thresholds. Potential perceptions of cost of falsely, and mistakenly, rejecting the active-learning hypothesis and parallel erroneous acceptance of a lecture-instruction hypothesis are shown.

Figure 3. Applying Hypothesis Testing to Changes in TeachingNote. Hypothesis testing involves a rational bias that is associated with asymmetric thresholds for acceptance and rejection for competing hypotheses (Trope & Liberman, 1996 ). The diagram illustrates the testing of a preferred focal hypothesis of lecture as a superior teaching strategy alongside an alternative hypothesis stating the efficacy of active learning. Notice the asymmetric thresholds for accepting and rejecting each hypothesis. Hypothesis testing occurs only if the current confidence in accepted knowledge is below all thresholds. Potential perceptions of cost of falsely, and mistakenly, rejecting the active-learning hypothesis and parallel erroneous acceptance of a lecture-instruction hypothesis are shown. The essential conclusion of the Trope and Liberman (1996) model is that a desire to avoid errors motivates hypothesis testing, such that reasoning along all of the paths in Figure 1 are the same, only the decision criteria (thresholds and costs) differ. Therefore, the outcome of motivated reasoning is entirely logical and rational, based on careful consideration of error costs and confidence thresholds. What differs among subjects representing the paths in Figure 1 are the costs of rejection versus acceptance of a new hypothesis that sets different confidence thresholds. From a persuasion standpoint, Trope and Liberman’s model requires faculty developers to look empathetically at these costs from the perspective of each faculty member and realize that a person focuses on a hypothesis with low acceptance costs that is desirable to present practice. Such a faculty member will not explicitly consider the merits of an alternative hypothesis unless the cost of false acceptance of the focal hypothesis can be increased, the cost of false rejection decreased, or both (Figure 3).

A faculty member may recall occasions when students did not attend a lecture, did not pay attention during lecture, performed poorly on exams, and provided negative teaching evaluations—all of which might lessen the rejection threshold of a focal hypothesis of the superiority of lecture and appear to open opportunities for persuasion. Or this experience may draw attention to the greater likelihood of an additional hypothesis, which Trope and Liberman (1996) call a “third variable interpretation,” that resists rejection of the preferred hypothesis and maintains the status quo. For example, the negative past experiences may be attributed to a student variable, such as poor work ethic or poor preparation for college, rather than the appropriateness of lecture instruction.

Activating Tipping Points

Pathway B and the dashed paths in Figure 1 imply that it is possible to shift a person toward Bayesian updating. The affective tipping point (Figure 1) is reached only when a significant amount of incongruent information exists to cause excessive anxiety that triggers change (Redlawsk et al., 2010). This happens when affective intelligence (Marcus & MacKuen, 1993) intervenes as new information is incongruent with existing beliefs, and the increasing threat to those beliefs generates an attitude change. Motivated reasoning does not involve Bayesian updating; instead, incongruent information is scrutinized for the purpose of rebutting it and strengthening current attitudes. Affective intelligence is a contrary process in which delayed Bayesian updating occurs because incongruent information eventually is scrutinized for the purpose of accuracy in order to decrease anxiety. Importantly, decisions are choices made at points in time, but evaluation is an ongoing process, so that affective intelligence can intervene and reverse motivated reasoning.

A high acceptance threshold for a new hypothesis is a natural asymmetric decision-making approach. Therefore, a teacher may initially appear resistant, leading to the premature judgment of motivated reasoning by an educational developer and other program participants. They need increasing information to reach a cognitive tipping point where there is sufficient dissonance to unfreeze knowledge acquisition about teaching and testing of the new hypothesis and its alternatives—not increasing anxiety to reach the affective tipping point—until the acceptance threshold is reached and accuracy is sought (Figure 1, path B). This is not a motivated reasoning pathway, but it requires patient, empathetic engagement by the developer to avoid disengagement by the initially skeptical faculty member.

Figure 1 also includes a potential cognitive tipping point along the motivated reasoning pathway. This hypothetical reversal of reasoning requires diminishing defensiveness to consideration of RBIS by approaches suggested above: activating values that favor change; avoiding threats to affinity groups and identity and nurturing networks with opinion leaders; using an existing prevention orientation before expecting eager promotion and risk; and decreasing the rejection threshold for a desirable hypothesis that is targeted for change so that resolution of cognitive dissonance shifts toward unfreezing closure and seizing new information.

Theoretical Basis for Motivated Reasoning and Persuading Change

From the earliest work of Kunda (1990), motivated reasoning has been described as a ubiquitous human behavior at the motivation-cognition interface, but a theoretical basis for that behavior and how it might change has received little attention. Establishing a theoretical framework is important because theory has predictive power for designing change interventions. As is apparent from the foregoing discussion, motivated reasoning activates individual values, anxiety, need for closure, tolerance for risk, self-image, identity, and relationships to those with common views that are part of hypothesis testing and decision-making. These are all aspects of individual well-being that are critical to learning and change and, therefore, well-being should be central to the theoretical foundation for explaining and responding to motivated reasoning.

The attitudes and behaviors illustrated by motivated reasoning and contrasting promotion-orientation pathways to personal change are explained by self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017). The core of SDT rests in the natural tendency toward flourishing and growth that depend on three interrelated psychological needs: Competence refers to the need to be effective by exercising one’s capacities to seek out and master challenges. Relatedness is the need to establish bonds with others. Autonomy describes the need to experience behavior as emanating from within so as to engage in learning with an internal locus of causality, a sense of freedom, and making choices.

Essential to the explanatory power of SDT in many fields is the importance of activities and success motivations that originate within the self rather than through external demands or the expectations of others. Positive perception of the psychological needs, especially autonomy, correlates with teachers’ pursuit of professional development and innovation (Gorozidis & Papaioannou, 2014) and with their selection of innovative instructional approaches (Stupnisky et al., 2018). Environments that generate well-being for growth and change must be competency supporting (versus overly challenging, inconsistent, discouraging), relationally supportive (and not impersonal or rejecting), and autonomy supportive (rather than controlling). SDT asserts that intrinsically motivated activities are inherently pleasant and enjoyable. Extrinsically motivated activities lie along a spectrum of increasing degrees of internal regulation and agency correlated with increasing support of autonomy, relatedness, and competency. Self-direction values, which are highly regarded by most people (Schwartz, 2012), are supported by internal regulation of decisions and actions.

Competence may be threatened by advocacy to pursue RBIS. A teacher may feel incompetent to execute unfamiliar strategies or have low self-efficacy and confidence to execute these changes. Without developing competence, a faculty member is unlikely to try an innovation or, if willing to try, will likely use a growth-limiting prevention orientation rather than a promotion approach (Higgins, 2000). Advocacy for RBIS may push a faculty member to innovate too quickly toward an “ideal state” that is beyond their zone of feasible innovation (Rogan & Anderson, 2011), leading to frustration. From a hypothesis-testing perspective (Trope & Liberman, 1996), there is a high acceptance cost for an RBIS alternative in place of current teaching practice because of challenges to teaching competency. The rejection threshold, therefore, is low, and preservation of self-worth leads to justification of current practice that is exhibited as motivated reasoning.

The relatedness need can be threatened in at least two ways by RBIS advocacy. First, changing to RBIS may threaten relatedness to peer or professional groups who value teaching less than scholarship, defend traditional ways of teaching that worked for them, and/or evaluate teaching performance differently than education researchers and educational developers (c.f., Kahan, 2012, 2013; Kahan et al., 2016). Hence, emotional and material support from others—friends, research colleagues, senior leaders in a department—are central to personal well-being. Therefore, rational rejection of change, evident by motivated reasoning, can be an individual judgment intended to enhance valued relationships (Haidt, 2001). A second threat is to the relationship with students, potentially reflected in poorer ratings of teaching that result from low-fidelity (incompetent) implementation (Smith & Herckis, 2018), learner motivation to reject a new teaching approach, or both. This threat exhibits the interrelationship of competency and relatedness needs for well-being.

Autonomy is a critical element of faculty well-being that can be threatened by even the best educational development intentions. Haidt (2001) argued for a coherence motive in motivated reasoning whereby a threat to a constructed view of oneself causes anxiety that one seeks to avoid through a biasing defense. If a faculty member self-identifies as an effective teacher, then it is possible that the manner in which RBIS is presented will trigger the boomerang effect as a defensive action against a threat to the instructor’s identity and self-worth (Trevors et al., 2016). To accept a refutation argument intended to persuade change in practice would mean rejecting a valued aspect of self-concept. Thus, refutation triggers an ego-protective response to restore a sense of self-worth (well-being) that undermines the refutation and strengthens the original belief that benefits from greater internal regulation. If change does occur at an affective tipping point (Figure 1), one can question if the prerequisite anxiety promoted well-being and growth. Regulatory fit during pursuit of a goal requires that a faculty member “feel right” about the approaches used to encourage achievement of a new goal (Cesario et al., 2008). A contrasting misfit occurs if one perceives the advocacy of RBIS as controlling rather than appealing to autonomous choice. Those with a promotion orientation are more strongly motivated to pursue a goal because the more valuable the goal, the higher the expectation of success to pursue the goal (Cesario et al., 2008). The goal for achievement and self-advancement means that the feel-right effect of promotion or prevention orientation is the endorsement and internal acceptance that accompanies autonomy in SDT.

Autonomy also explains the tendency for faculty to prefer their own teaching innovations, or those within their affinity group, to externally tested RBIS (Andrews & Lemons, 2015; Henderson, 2005; Herckis, 2018). While this phenomenon may not lead to motivated reasoning refusal, it does urge caution about leading with data to advocate change without invoking instructors’ current practices. Those existing practices link to individual beliefs and values, including the belief that they, and their teaching peers, already have the knowledge to improve their teaching.

Essential to persuading the use of RBIS is the motivation and internally regulated well-being of the faculty member who learns about innovative teaching and the extrinsically motivated challenges to adopt these innovations. These challenges relate to characteristics of higher education, such as multiple responsibilities, unbalanced reward systems for faculty, and unfamiliarity with teaching and learning scholarship in comparison to disciplinary knowledge (Svinicki, 2017).

Through the SDT lens, motivated reasoning is understood as preservation and pursuit of well-being through psychological needs. Persuading attitudinal change requires supporting those needs. Some of these needs and threats to autonomy exist beyond the educational development program and relate to professional learning in the workplace and institutional support that the developer must nurture (Lund & Stains, 2015; Smith & Stark, 2018). Self-determined well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017) is sustained through an autonomy-supportive, competency-supportive, and relational-supportive climate for professional growth as a teacher. Change expectations to extend beyond current teaching practice must remain within the zone of feasible innovation (Rogan & Anderson, 2011) so as not to injure autonomy and competence needs.

Persuasion in the Presence of Motivated Reasoning

Based on SDT, persuasion requires reducing threats to psychological needs that then permits deep processing of new information, either to avoid boomerang effects or to create cognitive tipping points (Figure 1). Conservation attitudes, cognitive closure, prevention orientation, and high rejection thresholds for current practice may, however, preclude persuasion. Despite abundant research on motivated reasoning, there are few studies that address persuasion processes that potentially change these attitudes. The few existing studies have the challenge of operational validity because they primarily involved controlled experiments rather than authentic learning and professional development contexts. This limited research does, however, allow inferences of potential change strategies, more likely useful in individual or small -group consultations than in workshops.

Consider the Opposite

Lord et al. (1984) extended the Lord et al. (1979) study documenting motivated reasoning regarding arguments for and against capital punishment. The participants were asked if they would make the same negative evaluations of the methodology had the study produced results compatible with their opinion on the issue. The difference in these evaluations was diminished substantially, and perceptions of the methodological quality of the prodeterrence study actually reversed (i.e., opponents of the death penalty rated a study supporting capital punishment higher than did the proponents). The authors concluded that initial beliefs persevere unless a person is required to consider the opposite and construct their own causal explanations of evidence that would be contrary to the arguments used to form their initial beliefs.

The consider-the-opposite intervention at a faculty development event might ask attendees to discuss the methodology of a pro-RBIS study (e.g., Freeman et al., 2014) independent of the conclusions, followed by discussion of the believability of the results. As a self-directed activity, considering the opposite retains the autonomy and supports the competence of the faculty learner. This approach is also consistent with Vosniadou’s (2001) view that effective persuasion requires explicitly considering conflicting points of view and not only contemplating one-sided arguments.

A related approach that I use solicits anonymous responses to a question regarding acceptance of research on alternative pedagogies to current practice followed by an activity in which small groups of faculty analyze data from motivated reasoning studies in various social, health, political, and scientific contexts (e.g., Hamilton, 2011; Kardash & Scholes, 1995; Koehler, 1993; Kunda, 1987; Lord et al., 1979). Applying the critical reasoning of their scholarly disciplines (c.f., identity-protective reasoning; Kahan et al., 2016), faculty correctly recognize the biases of the subjects in these studies. Then the participants are asked to self-examine and discuss how they may apply similar biases in their approaches to research about teaching, which typically surfaces statements about being more open-minded.

Solution Aversion

In studying politically motivated reasoning, Campbell and Kay (2014) proposed that self-preservation responses may be triggered not by a fear of the problem but by the fear of the solution. For instance, Republicans were more likely to agree with climate science in the context of free market–friendly solutions to reduce global warming than in the context of restrictive emissions policies. By analogy, educational developers should seek out if faculty motivation to discount RBIS relates most strongly to (a) threats to their self-image as a teacher or (b) averting the risks of the proposed solution, which might include expenditure of effort and time that is not valued either individually, within affinity groups, or institutionally. Acknowledging these latter risks through small, reversible solutions (e.g., use of think-pair-share or peer instruction, use of formative assessment) is more likely to engage a prevention orientation for change as a first step, and incrementally changing within the zone of feasible innovation may be more successful than starting with an argument for the essential need to change instruction. A focus on diminishing threats to instructors’ well-being supports their autonomy and competence.

Causal Argument

Persuasive discourse is commonly structured around arguments that are either anecdotal (cases, narratives), noncausal (statistical summary purporting to show a generalizable relationship), or causal (explanation of the cause of the effect) (Hoeken, 2001). The relative effectiveness of these argument types to changing attitudes or mental models are debatable because of variations in experimental design and few head-to-head studies of the approaches (Hornikx, 2005). Nonetheless, anecdotal arguments are viewed as least persuasive, and causal arguments are probably superior to noncausal ones. Refutation of misconceptions is commonly approached with statistical data presentations intended to provoke dissonance with a held belief or mental model. To be convincing, however, there must be a cause that explains the view to be adopted (Kardash & Scholes, 1995). Of particular relevance to persuasion when encountering motivated reasoning is the study by Slusher and Anderson (1996), who showed that causal arguments were more persuasive than statistical arguments in changing beliefs about the connection of HIV to AIDS, which was a controversial and polarizing topic at that time.

Noncausal arguments can readily open the door for motivated interpretation of the same data for a different outcome (Sarewitz, 2004). For example, one can attempt to persuade faculty of the importance of RBIS by citing the results of Freeman et al. (2014), who concluded that, on average, failure rates in introductory STEM courses increase by more than 50% under traditional lecture conditions compared with active learning approaches. However, it is also notable that in a quarter of the analyzed studies, the failure rates differed by no more than 5 percentage points or were higher in the active learning courses, which may lead a faculty member to argue that their costs of changing are unjustified by the research. Instead, using principles from psychology and learning sciences to argue from a causal standpoint may be more persuasive than trying to impress the audience with data. This practice is more likely to build competence through better understanding of why an RBIS approach works and how to implement it with fidelity (Smith, 2015; Stains & Vickrey, 2017).

Self-Affirmation

Viewing the boomerang effect (Figure 1) as an ego-protecting response to arguments that threaten one’s self-image leads to the suggestion by Trevors et al. (2016) that self-affirmation interventions would attenuate this effect. Steele (1988) established self-affirmation theory to explain that any threat to a person’s self-system of attributes, values, roles, beliefs, or identities disrupts one’s perception of self-worth, leading to defensive reactions or external attributions. Importantly, the converse is also true: self-affirming an important element of the self-system that is not directly threatened strengthens self-worth and mitigates against perceived threats. Self-affirming interventions, in which a person states values or attributes that make them a good person, lift psychological barriers to change both by lessening the perceived threat and curtailing defensive responses (Cohen & Sherman, 2014).

Given that motivated reasoning against RBIS may arise in response to threats to self-value and identity as a teacher, then biased reasoning and response may be alleviated if self-image and self-worth are bolstered ahead of encountering the threat. In cases of politically motivated reasoning, Nyhan and Reifler (2017) concluded that self-affirmation works to reduce the threat posed by attitude-inconsistent facts by strengthening an individual’s self-worth, thus allowing more thorough consideration of the evidence. Positive self-image also favors a promotion orientation rather than a prevention orientation to self-regulation of change processes (Bullens et al., 2014). Similar priming exercises, asking people to describe their hopes and aspirations in life, increases adoption of a promotion regulatory focus (Higgins, 2000). From the SDT perspective, self-affirmation enhances one’s sense of competence and autonomy and strengthens relationships with those in one’s close, value-sharing affinity groups.

Despite many recorded successes of self-affirmation exercises—increased openness to opposing political reviews, enhanced willingness to adopt health-promoting behaviors, diminished physiological reactions to stress, greater resilience to stereotype threat, higher academic achievement (Cohen & Sherman, 2014)—the untested application to educational development for adoption of RBIS is complicated. Subjects must not know the intention of the self-affirmation intervention or else the effect is negated (Silverman et al., 2013; Steele & Liu, 1983). Therefore, asking workshop participants to write about how they value themselves as a teacher would be methodologically unsound. Asking them to write about values that they live by, to self-assess strengths, or to participate in a values card sort activity (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) would be appropriate. Nonetheless, conducting a seemingly off-task activity may be off-putting to participants even though the facilitator expects a passive benefit to upcoming activities by diminishing threats to well-being and self-image that trigger motivated reasoning responses. Alternatively, these approaches may work as subliminal icebreakers in longer events, such as new faculty orientation and full-day or multi-day events. To the extent that universalism, benevolence, self-direction, and openness to change values emerge (Schwartz, 2012; Figure 2), it may be possible to then connect these self-identified values to the benefits of adopting RBIS.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivated reasoning arises from threatened psychological needs that are foundational to SDT, which draws attention to the therapeutic style of motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI developed empirically as a psychotherapy intervention, and SDT later became viewed as a theoretical model for explaining MI effectiveness (Markland et al., 2005; Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006). MI is advocated as an approach for educational development consultations with faculty (Talgar et al., 2015).

MI is a change conversation rooted in the common appearance of ambivalence: wanting and not wanting to change at the same time, seeing reasons to do so and not to do so (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). It is possible that faculty who refute or resist RBIS are ambivalent (see discussions on cognitive closure). They may possess positive attitudes about active learning that are, for instance, based on their own learning experiences or application in seminar or experiential courses that they teach. Nonetheless, they simultaneously hold negative attitudes generated from the additional effort to implement RBIS in large-enrollment courses, lack of affinity with a peer group that values RBIS in introductory courses, and/or poor teaching ratings. Therefore, their overall view is against active learning but with sufficient positive views about it as to be ambivalent.

The MI conversation elicits from the subject a greater amount of change talk than sustain talk for maintaining the status quo. MI is not a rigid method; rather, it is a person-centered spirit of conversation that seeks to have the subject strive toward a change strategy that works for them. This spirit is represented by (a) a partnership through exploring and supporting rather than persuasive argument; (b) accepting what the person brings shown through empathy, affirmation (accentuate the positive in what a person is doing), and autonomy; (c) compassionate commitment to pursue the best interests of the person; and (d) evoking the strengths, rather than deficits, of the person to succeed. MI honors the person’s autonomy, builds a new relationship with the facilitator while honoring those that exist, and utlizes the person’s competent strengths; thus, the connection with SDT.

In the context of this article, MI is a one-on-one conversation in which an educational developer avoids drawing on their expertise to provide answers to the person’s dilemma but rather draws out solutions offered by that person and awaits request for expert guidance. MI moves the developer from a directing communication style (provider of information, instruction, advice on how to change) to a follower style (listening, seeking to understand, evoking change talk). People trust their own opinions more than the opinions of others, particularly those outside an affinity group, which likely does not include educational developers in the case of a faculty member who is highly skeptical of or denies the efficacy of RBIS. Therefore, the focus of MI is to listen, empathize, and elucidate change through the talk of the faculty member while also building a relationship that leads to greater trust in the sought-after advice of the developer.

Ambivalence is critical to this approach because MI cannot manufacture motivation that does not already exist, even if admixed with resistance or refusal to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). There must exist some discrepancy between an unmet goal and the current status quo. Sometimes discrepancy must be instilled through conversation that reveals what the person is dissatisfied with (e.g., teaching ratings, student grades) and what they might consider changing (e.g., some aspect of teaching). If ambivalence does not exist and cannot be instilled, then MI approaches will not succeed.

Conclusions

Successful implementation of disseminated best practices in teaching requires persuasive strengthening and, commonly, changing attitudes that are rooted in individual values and those of peer and professional groups to which a faculty member holds an affinity. Educational developers usually encounter faculty members who are open to learning about RBIS and are willing to test focal RBIS hypotheses with relatively high rejection thresholds. Nonetheless, developers also encounter faculty who not only resist change but are overtly defensive of current practice and critical of evidence for RBIS alternatives. These faculty may also present barriers for RBIS implementation efforts by their colleagues through lack of departmental support.

Motivated reasoning to reject adoption of RBIS is a rational, logical, reasoned response to perceived threats to values, beliefs, and well-being, and it is not a cognitive deficiency. Standard approaches to persuasion that assume Bayesian updating and knowledge restructuring when confronting pro-RBIS data will not be successful when a person has reached cognitive closure on teaching methods; sets high rejection thresholds for a favored hypothesis along with high acceptance thresholds for alternatives; and perceives threats to autonomy, competence, relatedness, and personal identity and self-worth as a teacher. The multifaceted nature of motivated reasoning is well known from psychology and political science research, as is the herein proposed theoretical grounding in self-determination theory. Virtually unknown are the persuasive interventions for these circumstances. Designing workshops and planning consultations within the framework of self-determination theory that purposefully support faculty members’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness should decrease resistance and refusal. Using more inclusive forms of persuasion (e.g., causal), evoking participants’ values and perceived threats, triggering discipline-valued reasoning skills, providing for self-affirmation, and empathizing while listening rather than telling will likely be more successful than arguing with facts about student learning and expert urgency to change teaching practices.

In addition, it is critically important to remember that everyone applies motivated reasoning. Educational developers should self-reflect on their potential uncritical biases in favor of the instructional practices that they advocate. A change agent should always expect to benefit from postponing closure and constantly re-examine evidence and conflicting hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

My thinking about this topic benefited from conversations over several years with many people but most appreciatively with Craig Nelson, George Rehrey, and Anton Tolman. The manuscript benefited greatly from reviews by Judith Balacs Tomasson, Robert Giebitz, Craig Nelson, Aurora Pun, Lindsey White, and the journal’s reviewers and editors.

Biography

Gary A. Smith is Associate Dean of Continuous Professional Learning at the School of Medicine, and Professor in Organization, Information, and Learning Sciences at the University of New Mexico. He has directed educational development programs on both the main campus and the School of Medicine at the University of New Mexico

References

- Andrews, T. C., Conaway, E. P., Zhao, J., & Dolan, E. L. (2016). Colleagues as change agents: How department networks and opinion leaders influence teaching at a single research university. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(2), ar15. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-08-0170

- Andrews, T. C., & Lemons, P. P. (2015). It’s personal: Biology instructors prioritize personal evidence over empirical evidence in teaching decisions. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(1), ar7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-05-0084

- Bok, D. (2006). Our underachieving colleges: A candid look at how much students learn and why they should be learning more. Princeton University Press.

- Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and . . . tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163

- Bullens, L., van Harreveld, F., Förster, J., & Higgins, T. E. (2014). How decision reversibility affects motivation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 835–849. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033581

- Campbell, T. H., & Kay, A. C. (2014). Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 809–824. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037963

- Cesario, J., Higgins, E. T., & Scholer, A. A. (2008). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Basic principles and remaining questions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00055.x

- Clark, J. K., Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2008). Attitudinal ambivalence and message-based persuasion: Motivated processing of proattitudinal information and avoidance of counterattitudinal information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(4), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207312527

- Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137

- Eddy, S. L., & Hogan, K. A. (2014). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

- Epley, N., & Gilovich, T. (2016). The mechanics of motivated reasoning. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.133

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

- Ginns, P., Kitay, J., & Prosser, M. (2010). Transfer of academic staff learning in a research-intensive university. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562511003740783

- Gorozidis, G., & Papaioannou, A. G. (2014). Teachers’ motivation to participate in training and to implement innovations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.12.001

- Haak, D. C., HilleRisLambers, J., Pitre, E., & Freeman, S. (2011). Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology. Science, 332(6034), 1213–1216. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204820

- Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814

- Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.18809

- Halpern, D. F., & Hakel, M. D. (2003). Applying the science of learning to the university and beyond: Teaching for long-term retention and transfer. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 35(4), 36–41.

- Hamilton, L. C. (2011). Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change, 104(2), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9957-8

- Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211416646

- Hativa, N. (1997). Teaching in a research university: Professors’ conceptions, practices, and disciplinary differences [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL, United States.

- Henderson, C. (2005). The challenges of instructional change under the best of circumstances: A case study of one college physics instructor. American Journal of Physics, 73(8), 778. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1927547

- Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

- Henderson, C., & Dancy, M. H. (2007). Barriers to the use of research-based instructional strategies: The dual role of individual and situational characteristics. Physical Review Special Topics—Physics Education Research, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.3.020102

- Henderson, C., Dancy, M., & Niewiadomska-Bugaj, M. (2012). Use of research-based instructional strategies in introductory physics: Where do faculty leave the innovation-decision process? Physical Review Special Topics—Physics Education Research, 8(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.8.020104

- Herckis, L. (2018). Cultivating practice: Ensuring continuity, acknowledging change. Practicing Anthropology, 40(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.17730/0888-4552.40.1.43

- Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1217Hoeken, H. (2001). Anecdotal, statistical, and causal evidence: Their perceived and actual persuasiveness. Argumentation, 15, 425–437.

- Hornikx, J. (2005). A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies in Communication Sciences, 5(1), 205–216.

- Hynd, C. R. (2001). Refutational texts and the change process. International Journal of Educational Research, 35(7–8), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00010-1

- Kahan, D. M. (2012). Cultural cognition as a conception of the cultural theory of risk. In S. Roeser, R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, & M. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of risk theory: Epistemology, decision theory, ethics and social implications of risk (pp. 725–759). Springer.

- Kahan, D. M. (2013). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2182588

- Kahan, D. M. (2014). Making climate-science communication evidence-based: All the way down. In D. A. Crow & M. T. Boykoff (Eds.), Culture, politics and climate change (pp. 203–221). Routledge.

- Kahan, D. M. (2016). The politically motivated reasoning paradigm, part 1: What politically motivated reasoning is and how to measure it. In R. A. Scott, S. M. Kosslyn, & M. Buchman (Eds.), Emerging trends in social and behavioral sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0417

- Kahan, D. M., Hoffman, D., Evans, D., Devins, N., Lucci, E., & Cheng, K. (2016). “Ideology” or “situation sense”? An experimental investigation of motivated reasoning and professional judgment. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 164(2), 349–439.

- Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kardash, C. M., & Scholes, R. J. (1995). Effects of preexisting beliefs and repeated readings on belief change, comprehension, and recall of persuasive text. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20(2), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1995.1013

- Kendeou, P., Walsh, E. K., Smith, E. R., & O’Brien, E. J. (2014). Knowledge revision processes in refutation texts. Discourse Processes, 51(5–6), 374–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.913961

- Knight, P., Tait, J., & Yorke, M. (2006). The professional learning of teachers in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680786

- Koehler, J. J. (1993). The influence of prior beliefs on scientific judgments of evidence quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 56(1), 28–55. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1993.1044

- Kowalski, P., & Taylor, A. K. (2011). Effectiveness of refutational teaching for high- and low-achieving students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(1), 79–90.

- Kraft, P. W., Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2015). Why people “don’t trust the evidence”: Motivated reasoning and scientific beliefs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214554758

- Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing.” Psychological Review, 103(2), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.103.2.263

- Kunda, Z. (1987). Motivated inference: Self-serving generation and evaluation of causal theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.53.4.636

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

- Kunda, Z., & Sinclair, L. (1999). Motivated reasoning with stereotypes: Activation, application, and inhibition. Psychological Inquiry, 10(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1001_2

- Levitan, L. C., & Visser, P. S. (2009). Social network composition and attitude strength: Exploring the dynamics within newly formed social networks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(5), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.06.001

- Lord, C. G., Lepper, M. R., & Preston, E. (1984). Considering the opposite: A corrective strategy for social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1231–1243. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1231

- Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.37.11.2098

- Lund, T. J., & Stains, M. (2015). The importance of context: an exploration of factors influencing the adoption of student-centered teaching among chemistry, biology, and physics faculty. International Journal of STEM Education, 2(13). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-015-0026-8

- Marcus, G. E., & MacKuen, M. (1993). Anxiety, enthusiasm, and the vote: The emotional underpinnings of learning and involvement during presidential campaigns. The American Political Science Review, 87(3), 672–685. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938743