PannaFoto Institute: Teaching Photography and Building Communities

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The first draft of this essay was written in 2016 to mark the ten-year anniversary of the PannaFoto Institute. In this updated version, I will attempt to historicize PannaFoto, including the various initiatives that occurred before its establishment. Let me begin first with a partial mapping of communities directly or tangentially involved in photography in Indonesia.

Mapping Photo Communities[1]

In a 2012 discussion, artist Agung Kurniawan (b. 1968, Jember) and writer Antariksa observed that there had been an increase in photo collectives since the late ’90s, alongside the dissolving of the divide between art and photography.[2] Writing about the rise of video art communities within the same period, Edwin Jurriëns argues that they result from the “greater freedom of speech of the post-Suharto era, the globalization of information and communication networks, and the availability of increasingly cheaper and easier to handle media production and consumption equipment.”[3] These factors have also encouraged the growth of photo communities.

In fact, the evolution of Indonesian photography can be told through the various attempts, over the decades, for practitioners to band together. This is partly the result of the lack (and inadequacy) of formal photographic education in Indonesia before 1992, compelling people to pool resources and knowledge.[4] Here, I follow Jurriëns in defining communities as “groups of people with shared artistic and social interests who work collaboratively.”[5]

The influence of salon photography, which offers the dominant definition of art photography in Indonesia, is spread through the amateur photo clubs.[6] The oldest club still in existence originated from the Preanger Amateur Fotografen Vereniging (PAF) in Bandung, which was established in 1924. In 1954, PAF was renamed Perhimpunan Amatir Fotografie.

There are, of course, other communities operating beyond the framework of salon photography. Antara (founded in 1937) and the Indonesian Press Photo Service (IPPHOS; founded in 1946) take the form of agencies that supply photographs.[7] In 1994, with the help of curator-photographer Yudhi Soerjoatmodjo (b. 1964, Jakarta), the Antara Photojournalism Gallery (GFJA) launched its photojournalistic education program. Its alumni and those who now work for the news agency make up the informal Antara “family.”

Artists from the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru and the Decenta (Design Center Association) also used photography in their practices. In 1988, the Cemeti Gallery was established in Yogyakarta, turning the city into a key node in the production of contemporary art. Despite mounting photo exhibitions and offering residency opportunities, Cemeti’s cofounder Mella Jaarsma (b. 1960, Emmeloord) seems ambivalent about its impact on Indonesian photography. Nevertheless, she remains a good companion, especially for the Ruang MES 56 members, to discuss contemporary photography.[8] In existence informally since 1994, the Yogyakarta-based Ruang MES 56 is the most visible photo collective today, due partly to the success of its senior members in the art market. It is sometimes seen as the sole exemplar of contemporary photography in Indonesia.[9]

However, Forum Fotografi Bandung (FFB), active from 1984 to the mid-’90s, preceded them in proposing new ways to approach photography. FFB was a loose grouping of students, young creatives, and photographers with diverse interests in journalism, art, and music, united then in their interest in photography.[10] They mounted exhibitions in 1986 and 1988. Among the participating artists were Ray Bachtiar (b. 1959, Bandung), Arahmaiani (b. 1961, Bandung), Marintan Sirait (b. 1960, Braunschweig), and Krisna Ncis Satmoko (b. 1963, Bandung). FFB became inactive, the result of the diverging careers of its members and the lack of a strong ideological position that would provide the rationale for them to continue working within the collective.

To add to the plethora of photo communities in Indonesia, Erik Prasetya (b. 1958, Padang), Shamow’el Rama Surya (b. 1970, Bukittinggi), and the writer Nina Masjhur in 1994 established the now-inactive Klik Fotografi study group to discuss exhibitions and photographic discourses.[11] In 1998, Yudhi and Arbain Rambey (b. 1961, Semarang) cofounded Pewarta Foto Indonesia (PFI; Indonesian Photojournalists Association), an advocacy group that protects the rights of photojournalists to take pictures in public spaces.[12] The digitization of photography facilitated the emergence of Fotografer.net (FN), an online photo forum founded in 2002 by Kristupa Saragih (1976–2017, b. Jambi) and Valens Riyadi (b. 1975, Denpasar). FN offers its followers a platform to upload images, discuss photography, and trade equipment. It was, at one point, the largest photo community in Southeast Asia — more than 460,000 members in August 2014. Its offline activities, which include workshops and photo “hunting” trips, overlap partially with the salon clubs.[13] However, its popularity among photo enthusiasts has since been eroded by the proliferation of social-media platforms.

Reformasi, Friendships, and Beginnings

Triggered by the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the Reformasi (Reformation) movement led to the downfall of Suharto a year later. Edy Purnomo (b. 1968, Ponorogo) and Ng Swan Ti (b. 1972, Malang) belong to the generation of photographers who emerged during and after the Reformasi. Edy first studied photojournalism at GFJA in 1998; Ng made the leap into professional photojournalism in 2002, attending the World Press Photo (WPP) workshop in Jakarta.

Ahmad Salman (b. 1970, Semarang), on the other hand, has been an activist since 1988. In the ’90s, he worked at the Center for Human Rights Studies (YAPUSHAM) and the Legal Aid Institute, crossing paths with Munir Said Thalib (1965–2004, b. Malang). Leading up to the Reformasi, Ahmad worked underground, supporting the students and providing intercity connections. Recalling his turn to photography, Ahmad says:

One day, my friend said to me: “You are such a political animal. You take everything so seriously. You are not like human. There’s no fun talking to you.” I took it as a warning. I borrowed a camera from a friend and suddenly I found relief. I became humanized through the frame, through the lens.[14]

In 1997, he met Erik Prasetya and joined Klik Fotografi, and Erik became his mentor. Erik’s commitment to the photo-story format left a lasting impression. In 1998, Sinartus Sosrodjojo (b. 1975, Jakarta) graduated with a degree in economics from Occidental College, Los Angeles. His heart, however, was already with photography when he saw an Associated Press (AP) photographer exhibiting his images from Latin America in school. Because of the Reformasi, his family told him to stay in America, where he started his career in photojournalism. During the 1999 election, he returned to Indonesia for two weeks and became friends with Edy, who was then a stringer for Agence France-Presse (AFP). Sensing that Indonesia would be in the media spotlight for the foreseeable future, Sosrodjojo moved back in 2000 and made decent money as a freelance photojournalist. In 2001, after the September 11 attacks, he established JiwaFoto, a commercial photo agency based in Indonesia.

Among its roster of photographers were Edy, Ahmad, Ng, Roy Rubianto (b. Jakarta), and Saša Kralj (b. 1965, Zagreb). Shamow’el Rama Surya — whose 1996 photobook Yang Kuat Yang Kalah (The Strong Ones Are the Beaten Ones) inspired the likes of Ahmad, Ng, and Edy — joined JiwaFoto later.

JiwaFoto rode the wave for a few years, serving an enviable list of international editorial clients. Their interest in photo stories came naturally. Erik’s influence seeped in through Rama and Ahmad. It had made no sense for JiwaFoto to compete with AP, AFP, or Antara, which specialize in daily-news photography. When media focus shifted to China, around 2005, Sosrodjojo expanded the business into corporate work and design, which paid very well but stressed out the operations. Crucially, it diverted them away from what they wanted to do: tell stories from a humanistic angle. JiwaFoto began to wind down in 2007.

Between 2004 and 2006, Ng, Edy, Ahmad, Rama, Roy, and two other friends founded the Rana Foundation, driven by the desire to share their experiences in photojournalism.[15] They offered simple talks and seminars, typically one-off, in schools across Jakarta.

The yayasan (foundation) started serendipitously. In 2003, Edy was walking along Kuta Beach, photographing the recovery after the Bali bombing when someone tapped his shoulder and promptly invited him to share his work with the Jurnalistik Fotografi Club (JUFOC) members at University of Muhammadiyah Malang (UMM), East Java. There, Edy met Muflikh Farid (b. 1981, Malang), then a UMM student. That invitation rekindled Edy’s interest in education. His parents are retired educators who did not want him to become a teacher because it paid badly. However, Edy has always enjoyed sharing what he knows.

Ahmad’s interest in education stems from his politics: “Politics is about humans, about their past, present, and future,” he says. “Politics is about education, the development of human potential.”[16]

Looking back, Ahmad remembers how passionate and impoverished they all were. As other Rana members drifted away, usually because of family commitments, he got closer with Edy and Ng. Although they had married by then, the couple lived without the burden of raising a child or maintaining a swanky mansion. Born into a totok Chinese family, Ng studied in a public elementary school in the desa (village area) of Malang.[17] She was already an avid reader then, even though her family believed that buying books was a waste of money. Her family was neither rich nor poor. People in her extended family led typical Chinese lives as they opened shops in Java. “Education allowed me to take a different path,” Ng says. “It helped me chase my dreams and gain different experiences from my family.”[18]

In hindsight, Ng thinks Rana was handicapped by the lack of clear roles for its members. They wanted to do everything altogether, which resulted in arguments and frustration. Despite “a lot of shouting” at Rana, however, their friendships remained intact. “In Indonesia, people can’t talk openly about their disagreements,” Ng says. “This is the thing that distinguishes us from other collectives. We are used to arguing very hard. After that, I can still go home with Edy because we do not lose sight of our bigger mission.”[19]

PannaFoto Beginnings and the Malang Return

In 2005, the WPP Foundation in Amsterdam approached Sosrodjojo to see if he was interested in facilitating a teaching module in Jakarta. In 2006, after consulting his JiwaFoto peers, they established the PannaFoto Institute. The word panna (pronounced PA-nya) means “wisdom” in Sanskrit, indicating its focus in education. There was actually no requirement to set up a yayasan. Apart from distinguishing PannaFoto from the profit-making JiwaFoto, their decision was also informed by the collective dream of owning a gallery — a dream that remains unfulfilled today.

Edy and Ahmad were then sent to Amsterdam to train as trainers. Since then, the Edy-Ahmad tandem has been the bedrock of PannaFoto’s teaching initiatives. Sosrodjojo received the same training the same year. All of them remember the two-week stint as life changing. Michael Harrison, consultant trainer with thirty years’ experience at the BBC, led the sessions, which centered on how to teach effectively. In Indonesia, teachers usually deliver content as a monologue. At the WPP, they learned about activity-based learning, the use of visuals, and the relevance of a push-pull strategy. Other than suggesting a few links, the WPP did not peddle any content.

“The WPP was mainly interested in how we could teach in our environment without resorting to a Westernized approach,” Sosrodjojo explains. “They asked us to think about what was most needed in Indonesia. We built our modules based on how our society sees photography.”[20]

Surveying the ecology then, the PannaFoto team felt that there were already many organizations offering basic photography training, including Antara’s eight-month program in Jakarta. Therefore, they decided to focus on photo stories. Publicly, their program was advertised as a photo-editing workshop. It consisted of sixteen sessions, two sessions a week, spanning two months. Among the topics covered were: how to produce a photo story, marketing, lighting and portraiture, digital workflow, and visual literacy, which was then at a very early stage. The faculty consisted of Edy, Ahmad, Sosrodjojo, and Saša Kralj, with the visiting Jan Banning (b. 1954, Almelo). They developed the content internally, based on their working experiences, consulting with peers, and sourcing for references online and offline. Ng was offered the headmaster role but she declined. Nevertheless, she was involved in designing the curriculum and was present at all the workshop sessions. In effect, she became the program manager.

Even with the WPP providing a stipend to people who joined the workshop, it was really difficult to find applicants.

“We were offering something different from Antara, something that photographers here were not used to,” Sosrodjojo recalls. “It was hard even to sell Jan Banning. If the person is not revered locally, the photo community will tend to dismiss him.”[21]

From 2006 to 2007, PannaFoto graduated two batches of students, among them Muflikh Farid, Boby Noviarto (b. 1978, Jombang), and Antonius Riva Setiawan (b. 1974, Jakarta). The latter comes from the development sector. Before the PannaFoto workshop, in 2005, Antonius attended the Photojournalism Masterclass hosted by the VII Agency. He would become a partner of PannaFoto in 2008. Mamuk Ismuntoro (b. 1975, Surabaya), who joined the workshop in 2007, believes that the experience has made him more confident in shooting photo stories, leading to his breakout work, Tanah Yang Hilang (The Lost Lands, 2006–ongoing).[22] “Before the workshop,” he said, “I shot like Rambo. Now, I shoot like a sniper.”[23]

Based in Surabaya, Mamuk started Matanesia in 2006 as a blog dedicated to photojournalism. Boby quickly came onboard. Since then, Matanesia has become a community that runs public discussions and free workshops on photojournalism, using some of the teaching materials developed by PannaFoto.

When the WPP funding ended, in 2007, PannaFoto entered a period of uncertainty. From 2008 to 2010, Sosrodjojo was a consultant for the Media Indonesia newspaper. He spent his money to maintain the PannaFoto office for a year and a half before closing it down. In the interim, Antonius ran a few workshops, crossing paths with Yoppy Pieter (b. 1984, Jakarta). Yoppy was still in the advertising industry then, learning photography and writing on the side. In 2010, he received an invitation from Antonius to join his workshop at PannaFoto. Padang-based Allan Arthur (b. 1982, Padang) also joined the class.

Meanwhile, informed by her fascination with development work and the lack of photojournalistic initiatives outside of Jakarta, in 2008 Ng returned to her hometown to set up Malang Meeting Point (Mamipo). Also a yayasan, the founding members included Ahmad, Muflikh, and designer Bobby Haryanto (b. 1972, Brebes). Despite Ng’s background in photography, Mamipo became a place for people interested in cinema and youth culture, as well as photography, to exchange ideas. It also tapped into the dissipating energy of Insomnium, which had become dormant by then.[24] Founded in 2003, Insomnium was a collective dedicated to contemporary photography and inspired by Ruang MES 56.

Mamipo enabled the education initiative of Ahmad and Ng to briefly surface through the framing of “alternative art spaces” in the 2010 exhibition, Fixer: Exhibition of Alternative Spaces & Art Groups in Indonesia. The curator was Ade Darmawan (b. 1974, Jakarta), founding member of the Ruangrupa collective in Jakarta. It was also during his time with Mamipo that Ahmad became interested in curating. And through the collective, Ng earned a fellowship to go to New York to learn more about managing nonprofit organizations.

While Muflikh handled the daily operations in Malang, the fact that Ng, Ahmad, and Bobby were based in Jakarta made it difficult to manage Mamipo. Ng was also spending her savings to keep it afloat — a stressful sacrifice, to say the least. In 2011, Mamipo lost its venue, which dealt it a deathblow. In hindsight, she believes that Mamipo tried to be a platform for too many initiatives beyond photography. Nevertheless, it has inspired newer communities to emerge, such as Walking in Ngalam. Founded in 2012, its members include Arif Furqan (b. 1989, Malang) and Ichwan Susanto (b. 1978, Banyuwangi). They organize talks, workshops, and exhibitions on street and documentary photography.

From 2009 to 2010, Mamipo initiated two editions of the Malang Sekarang! (Malang Now!) workshop, in line with its aim to provide photographic education outside of Jakarta. With Edy as the main tutor, Ichwan and former JUFOC member Radityo Widiatmojo (b. 1984, Pasuruan) benefited from the initiative.

“Edy is a big believer in using photography to address city issues, to record the now instead of imagining the nostalgic past,” Ng says. “The workshop is a chance for us to make a visual history of our environment when we are still around.”[25]

Bearing Fruit

Serendipity knocked again in 2011, when Antonius received a call from the corporate social responsibility (CSR) arm of PermataBank, asking to collaborate with PannaFoto. It led to the creation of the Permata Photojournalist Grant (PPG), which builds on the WPP workshop template.

Sosrodjojo elaborates:

PermataBank wants to tackle the quality of reporting in Indonesia, which impacts them directly. We address the photography component. The PPG is a sexy program because it touches on empowerment and education. Photography is also very visual, easy to do exhibitions. That’s why they’re attracted to it.[26]

After having clinched the project, Antonius had to move to Sri Lanka for a high-profile job opportunity. With his hands tied managing his new company, Sosrodjojo gave Ng a call. Since then, she has assumed the roles of PPG headmaster and PannaFoto’s managing director. The PannaFoto Institute has since organized nine editions of the workshop, one annually.

Despite Permata offering 7.5 million rupiah for each participant to join the PPG, it was still difficult to find applicants. On the other hand, Yoppy, Muhammad Fadli (b. 1984, Bukittinggi), Fernando Randy (b. 1988, Jakarta), and Rosa Panggabean (b. 1982, Jambi) needed no convincing.

Reflecting on the evolution from the WPP workshop, Ahmad says:

Our content has broadened in PPG. It reflects our maturity as mentors. PPG is more structured, more fun. We do not wish to clone our styles on the participants. We often challenge them: “Make a mistake and learn from it!” There is a strong understanding between Edy and me. This is stronger than having a common doctrine.[27]

The visual literacy class has also become an important part of the PPG. During the WPP workshop, it was limited to a brief introduction on the formalistic qualities of photography. Building on the earlier version, the current module offers a brief intro to gestalt psychology and semiotics. The PannaFoto team believes that with visual-literacy training, practitioners will be able to edit their work in a more logical way.

In 2012, Erasmus Huis (the Dutch Cultural Centre) in Jakarta and the Netherlands Embassy became partners of the PPG, which allowed PannaFoto to invite Kadir van Lohuizen (b. 1963, the Netherlands) from NOOR Agency to serve as its visiting mentor.[28] During the third edition, in 2013, the PPG finally recorded a spike in applicants. Since 2014, PannaFoto has also sent one successful applicant each year, selected based on merit from the alumni and current participants of the PPG, to Amsterdam for a week. During the stay, the selected participant would work on a photo story under the mentorship of van Lohuizen and attend the WPP Awards Days. This fellowship is made possible with the support of Erasmus Huis.

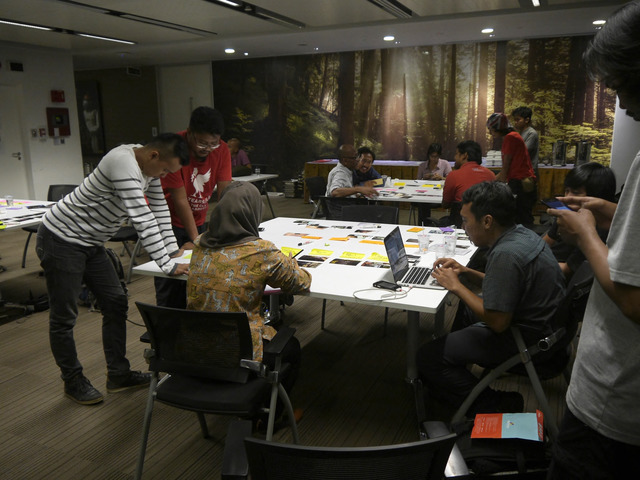

Fig. 1. 11 December 2015, Jakarta, © Zhuang Wubin, courtesy of the artist.One of PannaFoto's key initiatives is the Permata PhotoJournalist Grant (PPG), an annually-recurring 16-session workshop (two sessions per week) dedicated to the crafting of photo documentary. This is the first editing session of this year's workshop, hosted at the HQ of PermataBank, World Trade Center II, Sudirman.

Fig. 1. 11 December 2015, Jakarta, © Zhuang Wubin, courtesy of the artist.One of PannaFoto's key initiatives is the Permata PhotoJournalist Grant (PPG), an annually-recurring 16-session workshop (two sessions per week) dedicated to the crafting of photo documentary. This is the first editing session of this year's workshop, hosted at the HQ of PermataBank, World Trade Center II, Sudirman.Looking back, many of the PPG participants remember the workshop as an open space to explore different ways of using photography. In the 2011 edition, Yoppy used double-exposure film photography to create Student Brawl (2011), which evokes the mindscape of students who get into deadly fights. Fernando Randy (PPG 2012) used his background as a theater major at the Jakarta Institute of Arts (IKJ) to produce The Idol (2012). In these collaborative portraits, students are seen with their faces half-concealed by cut-outs of their favorite idols from Korea and Hollywood. “PannaFoto opened my eyes to the world of photography,” Fernando says. “I realized that contemporary photography does not have to be pretentious or fake. It can take on responsibilities.”[29]

Muhammad Fadli (PPG 2012) credits the workshop for changing the way he thinks and the way he sees things.[30] In 2014, he, Yoppy, and Bali-based Putu Sayoga (b. 1986) founded the Arka Project, a collective-agency promoting the three emerging photographers. Says Yoppy: “Arka Project and PannaFoto are not separate entities. Arka Project is inspired by PannaFoto.”[31]

Rosa Panggabean (PPG 2011), the first to win the fellowship to Amsterdam in 2014, describes the experience as “precious.” She says, “In Indonesia, we are still debating whether text or photography is more important. This debate is over in Holland. Photography is fully accepted as part of journalism.”[32]

With PPG fully entrenched in the ecology of photo initiatives in Jakarta, PannaFoto has been able to expand its other activities. Since 2013, the visual-literacy class has also become a stand-alone, one- or two-day program, benefiting the likes of curator Irma Chantily (b. 1985, Jakarta), Ridzki Noviansyah (b. Bandar Lampung), and the Surabaya-based photographer Romi Perbawa (b. 1971, Kutoarjo). The training that Edy, Ahmad, and Sosrodjojo received at the WPP Foundation on teaching pedagogy has become the template for its Training of Trainers (ToT) program, which PannaFoto started offering in 2014, benefiting educators and photographers like Kurniadi Widodo (b. 1985, Medan) from Yogyakarta and Danny Wetangterah (b. 1977) from Kupang.

Malang Sekarang! has been reconfigured into the three-day Aku dan Kotaku (Me and My City) workshop, bringing photographic education to provincial cities. After the inaugural edition in Jakarta in 2014, the three that followed in 2015 —Bukittinggi in West Sumatra; Malang in East Java; Kupang in East Nusa Tenggara — have been taught by Ng. The funding model differs for each edition, with PannaFoto and the local hosts sharing the costs. Ng does not charge for her tutoring, as she uses the traveling to understand what the photo communities outside of Jakarta need in terms of education. Aku dan Kotaku continues to be oriented toward the city. Through this framing, applicants at any competency level can pursue documentary work or something entirely personal.

Padang-based Muhammad Ridwan Anis (b. 1989, Jakarta), who joined the Bukittinggi workshop, says, “In West Sumatra, most photographers shoot only models or landscapes. PannaFoto brings something different to us. Even now, I still contact Ng online. But the personal touch is important. It is better for PannaFoto to come and teach us.”[33]

The Photobook as Method

In Indonesia today, there is an unmistakable spike in interest in photobooks. This “craze” has taken a long time to germinate. Since the JiwaFoto days, Ng, Ahmad, Edy, and Sosrodjojo have been trying to make photobooks. The result of their failed attempts is the number of unpublished dummies chucked and then forgotten in their homes. In 2008, with the support of the German Photobook Prize, Antonius initiated a long-term relationship with the Goethe-Institut Indonesia to mount photobook exhibitions.

During the first, in 2008, around one hundred books were on display, and just twenty people attended the opening. “This is why I’m grateful to have committed partners,” says Ng. “Education is a long-term investment. It is not easy to see the results immediately.”[34]

In 2011, Ahmad set up Buku Fotografi Indonesia (Photo Books Indonesia) on Facebook, and invited members to post photographs of their photobooks into the group. In effect, it has helped to crowd-source the history of photobooks in Indonesia. In that same year, photobook evangelist Markus Schaden (b. 1965, Cologne) led a workshop in Jakarta, inspiring the likes of Yoppy and the Antara photographer Fanny Octavianus (b. 1977, Purbalingga).

Since April 2012, with the support of PannaFoto, Ahmad and the late photojournalist Julian Sihombing (1959–2012, b. Jakarta) initiated a series of Kumpul Buku (Books Gathering) in Jakarta. The event incorporates a bazaar of new and used photobooks, book-signing sessions, and public forums. Visitors are encouraged to share their photobooks during the gathering. Kumpul Buku has since inspired similar events in Surabaya, Bandung, Solo, and Yogyakarta.[35] With Kumpul Buku and Photobook Club Kuala Lumpur as references, Ridzki Noviansyah and Tommy N. Armansyah (b. 1974, Bandung) cofounded the now-dormant Photobook Club-Jakarta in 2013. In its active phase, it organized regular public forums to discuss photobooks from around the world.[36]

In 2012, with the PannaFoto Institute as the publisher, Ng decided to give another shot at photobook publishing. Without financial support, she thought it would be safer to publish a book for Edy, “who has no worry about his prestige as a photographer.”[37] Ahmad and the designer Bobby Haryanto worked on it pro bono. The first print run of Passing was a tentative two hundred copies. When everything was reserved before the launch, PannaFoto made another five hundred copies for the second printing. Their initial uncertainty can be seen in the size of the photobook, which measures 16 cm by 14 cm. For the educator-photographer Radityo Widiatmojo, though, its portability is Passing’s enduring quality. While taking a breather or waiting for the train, Radityo can flip through a few photographs and transport himself into a different world.[38]

Since then, PannaFoto has published Ng’s Illusion in 2014, Mamuk’s Tanah Yang Hilang in 2014, and Yoppy’s Saujana Sumpu in 2015. The yayasan does not finance any of these photobooks. Each is financed differently — through private patronage, discounts in materials, or crowdfunding.

“We do this not for profit,” says Ng. “We want to make an artifact for Indonesian photography. This is why we keep our pricing affordable. I’m happy when people in Kupang or Makassar can look up these Indonesian photobooks and learn.”[39]

In 2014, PannaFoto organized another photobook exhibition, in Kemang, in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut Indonesia. The Japan Foundation contributed to the event with a selection of Japanese photobooks. More important, PannaFoto invited Ahmad, Kurniadi, and publisher Lans Brahmantyo (b. 1966, Surabaya) to curate twenty Indonesian photobooks for the exhibition. In this way, they have started historicizing the photobooks in Indonesia. Collaboration among the three institutions occurred again in 2016, resulting in two exhibitions.

Fig. 2. 5 November 2016, Jakarta, © Edy Purnomo, courtesy of the artist.In partnership with Goethe-Institut and Japan Foundation Jakarta, PannaFoto Institute organizes "Pameran Buku Fotografi 2016" at GoetheHaus, Jakarta. The exhibition showcases selected photobooks from Indonesia, Japan, and the annual Deutsches Fotobuchpreis (German Photobook Award) in Germany.

Fig. 2. 5 November 2016, Jakarta, © Edy Purnomo, courtesy of the artist.In partnership with Goethe-Institut and Japan Foundation Jakarta, PannaFoto Institute organizes "Pameran Buku Fotografi 2016" at GoetheHaus, Jakarta. The exhibition showcases selected photobooks from Indonesia, Japan, and the annual Deutsches Fotobuchpreis (German Photobook Award) in Germany.Small Victories[40]

My trip to Indonesia in December 2015, in preparation for this article, coincided with the 2015 Jakarta Biennale, which featured the photographs of Yoppy and Ng. This is not the first time straight photography is being featured in the biennale. At the 1993 event, the art historian Jim Supangkat (b. 1948, Makassar) had already exhibited the photographic works of Yudhi, Fendi Siregar (b. 1949, Madiun), and Tara Sosrowardoyo (b. 1952, New York). Nevertheless, it is the exception rather than the norm for documentary photography to cross into the more prestigious or commercial art events in Indonesia. Hence, the selection of Ng and Yoppy in the biennale represents a small victory.

Earlier that year, at a roundtable on photo communities in Indonesia during the inaugural Bandung Photo Showcase, participants agreed that regeneration is one of the most pressing issues they face.[41] To this end, PannaFoto has started involving younger mentors like Yoppy and Rosa in the PPG. Fernando Randy also suggests inviting people beyond photography into the fold of PannaFoto.

Ng speaks of the need to professionalize the operating roles within the yayasan, so that others can eventually take over PannaFoto. She brings leadership qualities and a focus on details to the table, but Ng works intuitively. Her emotional connection to her friends is key here. As a counterpoint, Sosrodjojo looks at PannaFoto partially as a business. This gives him a sense of detachment to ask the practical questions: Are “customers” returning to PannaFoto? On how many people have they had an impact? What if PermataBank cuts the funding for PPG?

Fig. 3. 6 July 2019, Jakarta, © Zhuang Wubin, courtesy of the artist.Sarinah shopping mall, Jakarta International Photo Festival, 2019.

Fig. 3. 6 July 2019, Jakarta, © Zhuang Wubin, courtesy of the artist.Sarinah shopping mall, Jakarta International Photo Festival, 2019.In 2019, PannaFoto mounted the inaugural Jakarta International Photo Festival (JIPFest), with the main events at the Ismail Marzuki Park (TIM) and neighboring venues in central Jakarta. It featured an open call for submission (on the theme of “Identity”), portfolio review, public talks, and workshops. The second edition of JIPFest is scheduled to open in June 2020, centred at the historic old town in North Jakarta. The festival theme is “Space” and its curatorial team consists of Sayed Asif Mahmud (Bangladesh), Kurniadi, and Ng. Not surprisingly, the increased visibility of PannaFoto due to the success of JIPFest 2019 has ruffled the feathers of some photo institutions and collectives across the country. However, if they channel their anxieties in a positive way, it might actually help to generate more critical initiatives relating to photography in Indonesia.

Here, I have tracked the evolution of PannaFoto since its inception and how it has benefited from and had an impact on other communities. However, the crossings charted here are broadly confined within the ecologies of straight and documentary photography. The art-versus-photography divide remains intact. In this sense, one of the challenges for PannaFoto is to cultivate and connect with new audiences, funding bodies, and even collectors, which will help to secure the sustainability of its various initiatives.

As a writer/curator, Zhuang Wubin focuses on the photographic practices of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. He uses the medium as a prism to explore the following trajectories: photography and Chineseness, periodicals and photobooks as sites of historiography, and photography’s entanglements with nationalism and the Cold War. Published by NUS Press, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey (2016) is his fourth book. In 2019, Zhuang received the J Dudley Johnston Award and Honorary Fellowship from the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain for that publication. The Chinese translation was published in 2019 by VOP BOOKS, Taipei.

Notes

See Zhuang Wubin, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey (Singapore: NUS Press, 2016), chapter Indonesia, for a more detailed mapping of communities in Java involved directly or indirectly with photography.

Ferdiansyah Thajib, “Living Expectations: Understanding Indonesian Contemporary Photography Through Ruang MES 56 Practices,” in Stories of a Space: Living Expectations; Understanding Indonesian Contemporary Photography Through Ruang MES 56 Practices, ed. Agung Nugroho Widhi (Jakarta: Indo Art Now, 2015), 181.

Edwin Jurriëns, “Sharing Spaces: Video Art Communities in Indonesia,” in Performing Contemporary Indonesia: Celebrating Identity, Constructing Community, eds. Barbara Hatley and Brett Hough (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2015), 98.

In 1992, the Jakarta Institute of the Arts (IKJ) launched its photography diploma program, probably the first in Indonesia.

See Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 38–49, for a history of the photo clubs in Java and how they propagate their influence through photo contests.

See Yudhi Soerjoatmodjo, Indonesian Press Photo Service (IPPHOS): Remastered Edition (Jakarta: Galeri Foto Jurnalistik Antara, 2013), for his detailed research into the Indonesian Press Photo Service.

Puthut EA, “Mella, MES 56, Metamorphosis,” in Stories of a Space: Living Expectations; Understanding Indonesian Contemporary Photography Through Ruang MES 56 Practices, ed. Agung Nugroho Widhi (Jakarta: Indo Art Now, 2015), 210–18.

Roy Voragen, curatorial essay for Deden Hendan Durahman: Amorphous Amours, exh. cat. (Kuala Lumpur: Richard Koh Fine Art, 2014), 17n3.

Sjuaibun Iljas, interview by the author, Bandung, June 11, 2013.

Erik Prasetya and Ayu Utami, Banal Aesthetics & Critical Spiritualism: A Dialogue of Photography and Literature in 13 Fragments (Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2015), 24.

Zhuang Wubin, “Revolution Photojournalism,” Grain, October 2004, 51.

See Strassler, Refracted Visions, 30–35, 62, for a brief overview of the socio-cultural context of photo “hunting” excursions in Indonesian salon photography.

Ahmad Salman, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 14, 2015.

Sinartus Sosrodjojo and other JiwaFoto photographers were not involved in Yayasan Rana.

See Mely G. Tan, “The Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia: Issue of Identity,” in Ethnic Chinese as Southeast Asians, ed. Leo Suryadinata (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1997), 42, who explains that the peranakan are “those who are of mixed descent, whose families have settled in Indonesia for at least three generations, who may have had some Chinese language school education but do not speak Chinese as the home language, and whose cultural orientation is more towards the culture of the area in which they have settled.” The term totok is used to refer to “newly arrived” Chinese families who have not been in Indonesia for more than three generations. Within the present context, due to the relative success of Suharto’s assimilation policies, most Indonesian Chinese no longer have any affinity with Chinese culture or history, further complicating the demarcation between totok and the peranakan.

Ng Swan Ti, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 13, 2015.

Sinartus Sosrodjojo, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 12, 2015.

See Zhuang Wubin, “Out of Focus: Independent Photography in East Java,” Art Monthly Australia, October 2011, 44–45, for a brief profile of Mamuk Ismuntoro’s photographic practice.

Mamuk Ismuntoro, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 15, 2015.

See Zhuang, “Out of Focus”, 45–46, for a brief history of Insomnium.

Ng Swan Ti, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 14, 2015.

More recently, the curator Jenny Smets has replaced Kadir van Lohuizen as the PPG’s visiting mentor.

Fernando Randy, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 12, 2015.

Muhammad Fadli, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 12, 2015.

Yoppy Pieter, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 12, 2015.

Rosa Panggabean, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 17, 2015.

Ridwan Muhammad, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 12, 2015.

Ahmad Salman, Facebook message to the author, July 11, 2016.

Ridzki Noviansyah, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 15, 2015.

Radityo Widiatmojo, interview by the author, Jakarta, December 16, 2015.

See Charles Esche, “Neither Forward nor Back,” in Jakarta Biennale 2015: “Maju Kena Mundur Kena: Bertindak Sekarang,” exh. cat., ed. Ardi Yunanto (Jakarta: Yayasan Jakarta Biennale, 2015), 21, in which the lead curator of the 2015 Jakarta Biennale suggests that the reason “why we keep doing things, why artists develop their projects, why people go to see them” is our collective hope for “small victories.”

See Aditya Pratama, “Roundtable Discussion: Photo Communities in Indonesia,” writing photography | se asia (blog), March 17, 2015, https://writingfoto.wordpress.com/2015/03/17/roundtable-discussion-photo-communities-in-indonesia/, for an excellent summary of the roundtable discussion. I would like to thank the Faculty of Fine Arts, Chiang Mai University, where I worked as a special visiting lecturer in 2015 for the Photographic Art Division, for supporting my return trip to Bandung.