Surface Tension: Hong Kong Photographs in Wei Leng Tay’s Abridge Project

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In 2018, Wei Leng Tay began a new project and returned to Hong Kong to start the familiar process of interviewing the subjects she proposed to video and photograph, this time working more with an older generation of southern Chinese migrants, many of whom had swum or hiked illegally, in the 1950s and 1960s, to the quasi-mythical safe haven of the British colony. On the same trip, she took video of her bus trip along the newly completed Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, the world’s longest sea bridge, a 55-km-long stilted highway. Tay was interested in the intersection of these migrant histories with a huge infrastructural construction that seemed to formalize the contentious political, economic, and social integration of Hong Kong to Mainland China.

During a follow-up trip, in 2019, the Hong Kong protests, opposing a proposed extradition bill to Mainland China, intensified. Tay felt uneasy about recording the faces of her informants, many of whom told tales of escaping hardship, uncertainty, even persecution in Maoist China, memories that were also increasingly woven into the conflict unfolding on the streets. Her sensitivity to the role of images was heightened amid the massive circulation of protest photographs and videos, which sought to define the public understanding of the frontline.

“It made me think of the kind of photographs that I’ve been taking for the last decade,” she said. “For a lot of them, you don’t see those kinds of images anymore. Like the photographs that I’ve taken of the Hong Kong families: The kind of places that I would photograph them, it’s like daily life. It’s looking at the ways that people would go about, you know; how they were living with different layers of history in their own homes, or things like that. That seems, not flippant, but unimportant at this point, when images are being used, or instrumentalized for something else. It feels a bit indulgent to be doing that. Thinking about it, it’s also because I was using medium-format film, and right now that feels archaic because digital photography has moved so quickly.”[1]

Unwilling or unable to picture the people she interviewed, she grappled with how and what to photograph, if anything, while becoming increasingly sensitive to the mediation of the conflict through the images streamed onto her mobile phone. The relationship between her previously film-based practice and the predominance of digital photography in her work prompted further exploration of the photographs she had previously taken, their form and context, how such intentionality could change from the contemporary vantage point.

“I moved to digital for my own work at the end of 2015,” she said, “because I was in Pakistan, for a residency, and they wanted something at the end of it. It was quite a pragmatic decision to use my digital camera, because they couldn’t process the scans in time. But when you have stepped into digital, to move back into film again becomes very difficult, in the sense that there has to be a good reason.”[2]

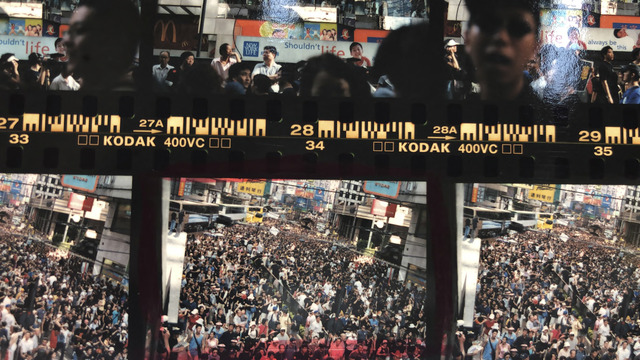

These questions, about the role of photographs in documenting Hong Kong today and her own long period of photographing on the “archaic” medium of film in this place, led her to start producing a set of images based on re-photographing, with her phone, her earlier slides and contact sheets. Her earlier images, on 35 mm and medium-format slide film, were made across a decade and a half in which post-Handover Hong Kong grappled with social crises such as SARS (Fig. 1), as well as persistent political challenges, among them the first large-scale public protests, against the proposed anti-subversion bill, Article 23 (1 July 2003) (Fig. 2)

Fig. 1. Wei Leng Tay, A boy at Repulse Bay beach during SARS, 2003. Kodak E100VS slide, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

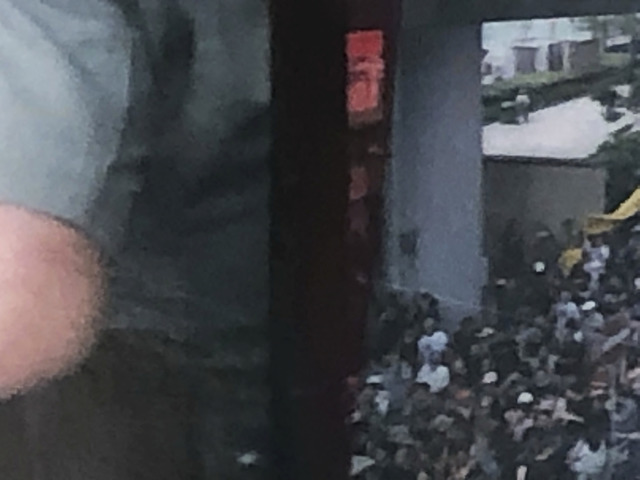

Fig. 1. Wei Leng Tay, A boy at Repulse Bay beach during SARS, 2003. Kodak E100VS slide, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 2. Wei Leng Tay, Article 23 protest, Causeway Bay, 1/7/2003. Contact sheet, Kodak 400VC negative, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 28.125x50cm, edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

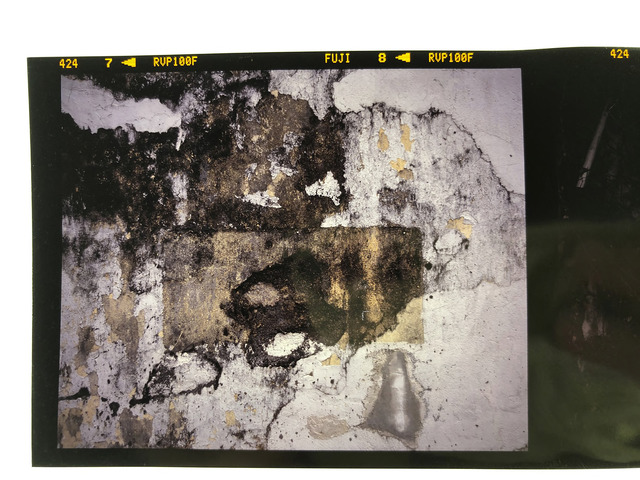

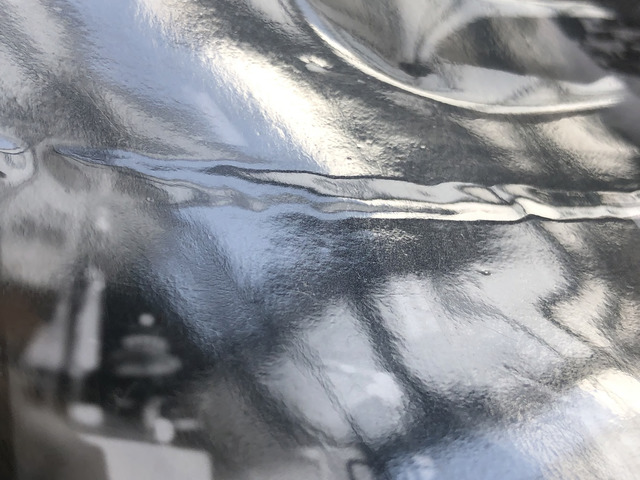

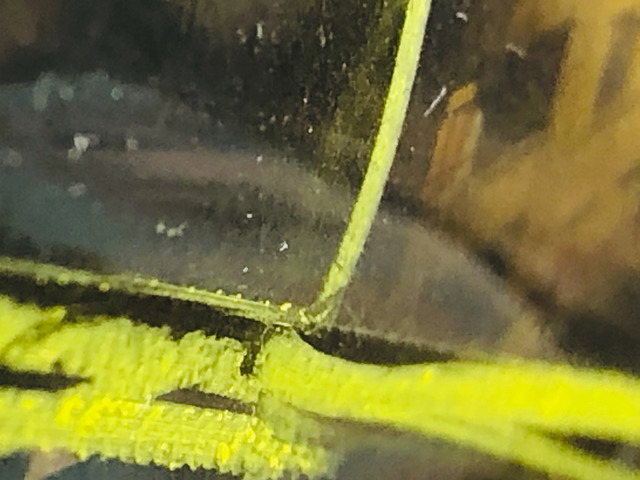

Fig. 2. Wei Leng Tay, Article 23 protest, Causeway Bay, 1/7/2003. Contact sheet, Kodak 400VC negative, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 28.125x50cm, edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.For this set of photographic prints, which forms one part of her upcoming Abridge exhibition project, Tay has been re-photographing whole or partial images of slides and contact sheets, sometimes the space between negative frames (Fig. 10), or photographs of the slides on a lightbox or window (Fig. 9), or pictured through a warped, reflective negative sleeve (Fig. 5) The result is often visually layered, manipulating translucent and reflective surfaces to distort and reimagine the images as objects, artifacts, or perhaps remnants. Tay then attempts to make each image into a finished “good print,” using specific sizes of archival digital paper. This pseudo-systematic formal exploration chafes against the limitations of the iPhone (Fig. 8) creating complex parallels to the ongoing interview process with Mainland migrants, tangentially expressing the complexity of Hong Kong identity and, perhaps for the first time, her own position in that landscape.

Fig. 3. Wei Leng Tay, Kai Yuen Lane missing sign, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 3. Wei Leng Tay, Kai Yuen Lane missing sign, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 4. Wei Leng Tay, Barney Cheng fashion show, 2001. Fuji RMS slide, 35mm, 2020. Archival pigment print, 60x80cm (23.62x31.50 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 4. Wei Leng Tay, Barney Cheng fashion show, 2001. Fuji RMS slide, 35mm, 2020. Archival pigment print, 60x80cm (23.62x31.50 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 5. Wei Leng Tay, Causeway Bay, 2001. Contact sheet, Kodak Tri-X 400, 120mm, 2020.Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 5. Wei Leng Tay, Causeway Bay, 2001. Contact sheet, Kodak Tri-X 400, 120mm, 2020.Archival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 6. Wei Leng Tay, Ming Yuen West Street, 2010, Kodak E100VS slideArchival pigment print, 45x60cm (17.72x23.62 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 6. Wei Leng Tay, Ming Yuen West Street, 2010, Kodak E100VS slideArchival pigment print, 45x60cm (17.72x23.62 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 7. Wei Leng Tay, Ming Yuen West Street, 2010, Kodak E100VS slideArchival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

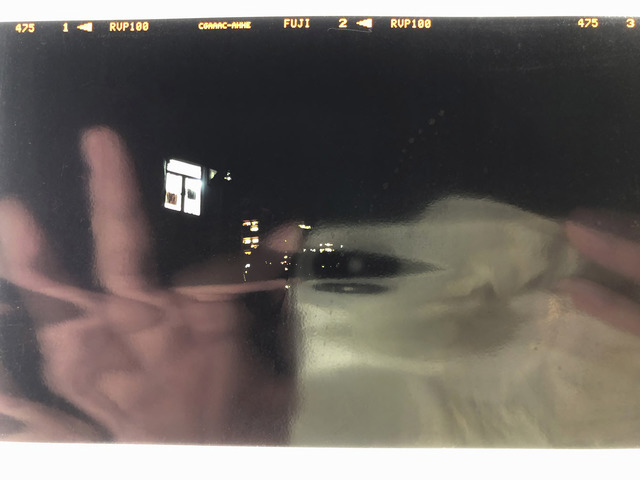

Fig. 7. Wei Leng Tay, Ming Yuen West Street, 2010, Kodak E100VS slideArchival pigment print, 75x100cm (29.53x39.37 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 8. Wei Leng Tay, View from Kai Yuen Street, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 90x120cm (35.43x47.24 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 8. Wei Leng Tay, View from Kai Yuen Street, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 90x120cm (35.43x47.24 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 9. Wei Leng Tay, Neighbor at Upper Kai Yuen Lane, 2009. Kodak E100VS slide, 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 37.5x50cm(14.76x19.69 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 9. Wei Leng Tay, Neighbor at Upper Kai Yuen Lane, 2009. Kodak E100VS slide, 120mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 37.5x50cm(14.76x19.69 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist. Fig. 10. Wei Leng Tay, Article 23 protest, Causeway Bay, 1/7/2003. Contact sheet, Kodak 400VC negative, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 45x60cm (17.72x23.62 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.

Fig. 10. Wei Leng Tay, Article 23 protest, Causeway Bay, 1/7/2003. Contact sheet, Kodak 400VC negative, 35mm, 2019. Archival pigment print, 45x60cm (17.72x23.62 inches), edition of 5, © Wei Leng Tay, courtesy the artist.“Stories of the past never catch up with the ever-vanishing present,” observed the Hong Kong writer P. K. Leung.[3] While based on photographs with specific referents, some personal some societal, Tay’s apparent abstractions in fact reinstate the objecthood of these images, their existence in a particular time and place. As their aspiration to inform is denied, they ironically assume a new materiality, in the present flux, rightly reflecting a past as only so many fragmentary glimpses, which can no longer be readily wrought into a nostalgic whole.

Olivier Krischer has edited, co-edited and authored publications including Zhang Peili: from Painting to Video (2019), the special issue ‘Asian Art Research in Australia and New Zealand: Past, Present and Future’, Australia & New Zealand Journal of Art (2016, with S. Whiteman), Asia through Art and Anthropology: Cultural Translation Across Borders (2013, with F. Nakamura, M. Perkins), and was previously managing editor of ArtAsiaPacific magazine in Hong Kong (2011-2012). His curatorial projects include Zhang Peili: from Painting to Video (2016, co-curated with Kim Machan), Weileng Tay: ‘The Other Shore’ (2016), and Between: Picturing 1950-60s Taiwan (2015). He is currently acting director of The University of Sydney China Studies Centre.