Photographic Praxis in China, 1930s–1980s: A Conversation with Chen Shuxia, Shi Zhimin, and Zhou Dengyan about Shi Shaohua and the Friday Salon

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

In September 2018, two photography exhibitions — Epic Through Shi Shaohua’s Lens, curated by Shi Zhimin and Zhou Dengyan, and A Home for Photography Learning: The Friday Salon, 1977–1980, curated by Chen Shuxia — opened successively in the National Art Museum of China and Taikang Space in Beijing. The exhibition about the photographer and high-ranking official Shi Shaohua in the most prestigious state art museum was in striking contrast with an exhibition on an amateur photo group in a not-for-profit, privately funded art space. The subjects of both shows, Shi Shaohua as a prominent official in the photography community of the People’s Republic of China and the Friday Salon as a nonofficial photo group active in private space, seemingly have an oppositional status but they somehow share similar treatment in Chinese photography history. For various reasons, the histories of both subjects have not been studied in great detail in the history of Chinese photography. Both exhibitions were the first attempt to present comprehensively these missing histories.

In the following conversation among Chen Shuxia, Shi Zhimin, and Zhou Dengyan, we learn about the making of the exhibitions and histories of both subjects, revealing the official and unofficial channels for image circulation in China between the 1930s and 1980s. The discussion also suggests reasons for the lack of research on such subjects and current pressing issues in the field of photographic history in China.

The Exhibitions: Making and Breaking “Typicality”

Zhou: Epic Through Shi Shaohua's Lens was a retrospective of Shi Shaohua (1918–1998), a pioneer photographer of the Eighth Route Army and a photography tutor at the Communist-led anti-Japanese base areas in North China. He became a cadre of the Party and served as deputy director of the Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial 晋察冀画报 from 1943 to 1948.[1] Except for being harshly persecuted in the first three years of the Cultural Revolution, Shi remained a leading figure in the Chinese photography community from 1949 to 1978. Over the past three decades, however, his name has seldom been mentioned in the historical narratives of photography in China, largely ascribed to his dramatically changed fortunes during the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath. As Shi Shaohua’s second solo show (the first one was in 1962), the exhibition we curated highlighted the photographer’s professional path from the years of the War of Resistance Against Japan (1937–45) to the early 1980s.

The exhibition began with a chronicle of Shi’s brief biography, illustrated with seventeen portraits of the artist and his colleagues from 1937 to 1995. The spectator was then guided to the museum’s main hall, which featured Shi’s best-known works. On the dark red wall of the main hall also hung the exhibition’s largest print, a 100 cm by 437 cm reproduction of a group portrait, in which one hundred and four acclaimed photographers from all over the country, included Shi, gathered in Beijing on December 22, 1956, right after their attendance of the founding conference of the China Photography Society中国摄影学会 (renamed China Photographers Association中国摄影家协会 in 1980). The fact that Shi was elected chair of the society during this conference was not the only reason for giving this document such a large format. We also considered it as a visual trace to bring the audience back to this “hundred flowers” moment in the history of Chinese photography.

Fig. 1. Museum installation of the group portrait of the China Photography Society’s first members. Photo by Shi Zhimin.

Fig. 1. Museum installation of the group portrait of the China Photography Society’s first members. Photo by Shi Zhimin.The majority of Shi’s work was structured chronologically and thematically in two galleries located on the main hall’s left and right wings. The left gallery highlighted four series taken during the War of Resistance: “The Yanlingdui Guerrillas,” “The Tunnel Warfare,” “Captain Dolan Visits Jizhong,” and “The Japanese People’s Emancipation League.” As spectators walked from the main hall to this gallery, they were given a broader context of where Shi’s famous photographs originally came from. The right gallery consisted of Shi’s lesser-known works, from 1946 to 1949, such as documentation of the Jin-Cha-Ji cinema team’s first sound film postproduction process, photographs of everyday life and training in the Jin-Cha-Ji military-political school, and the Chinese delegation’s participation in the World Peace Congress in Prague and activities after their return. Post-1949 works were displayed in the corridor gallery that connected the two wings, featuring the People’s Republic’s founding ceremony, portraits of cultural celebrities, and stage photographs of the famous “eight model plays” (yangbanxi 样板戏) during the Cultural Revolution. Archival materials such as contemporaneous working correspondences, manuscripts, and publications were also displayed to provide the spectator a sense of Shi’s working conditions.

Fig. 2. The museum's main hall features twelve of Shi's best-known works. The second one from the left, entitled Chairman Mao and Two Little Soldiers, was supposed to appear in the exhibition poster but was replaced by Two Little Brigades, the second image from the right.

Fig. 2. The museum's main hall features twelve of Shi's best-known works. The second one from the left, entitled Chairman Mao and Two Little Soldiers, was supposed to appear in the exhibition poster but was replaced by Two Little Brigades, the second image from the right.Chen: You just mentioned “four series” in displaying Shi’s photographic work taken during World War II. In your essay for the exhibition publication you also discuss Shi’s serial photographs and his concept of “typicality” (dianxingxing 典型性). Did his serial photography projects contribute in constructing this “typicality”?

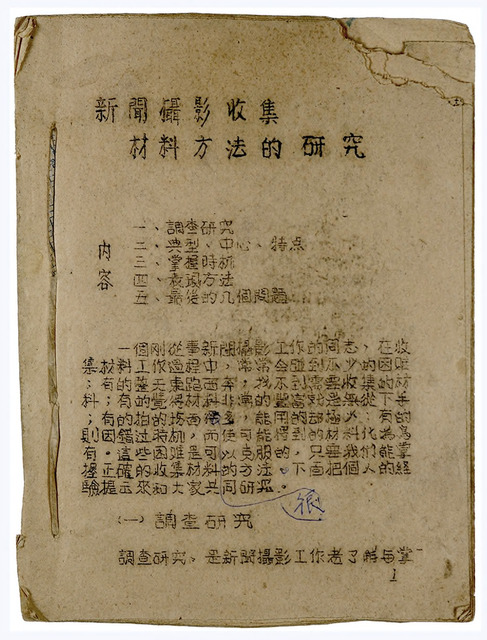

Zhou: Yes, exactly. Shi defined what was “the typical” (dianxing 典型) and provided a set of working methods in his lecture notes, The Study of Methods of Collecting Materials for Photo-Reportage (Xinwen sheying shouji cailiao fangfa de yanjiu 新闻摄影收集材料方法的研究), printed in 1944. “The typical” was derived from the Leftist literary conception of “typicality,” which dominated Leftist literary discussions in the early 1930s. But Shi’s appropriation was pragmatic. He echoed the Party’s direction for a “mass line” in cultural work and showed the particular influence of Mao Zedong’s instruction to Party cadres. “Mass line” was the Party’s organizational and leadership methodology developed by Mao. To apply this method in work, a Party cadre must not be self-absorbed but rather learn from and rely on the revolutionary grassroots. By investigating the real conditions of the local masses and participating in their struggles, the cadre would establish a close relationship with the people and orient organizational tactics to enforce the Party’s resulting polices. In my doctoral dissertation, I found Shi’s theory of “the typical” very useful for interpreting Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial’s editorial strategy, but whether that was also exemplary in his photography practice remained unresolved.[2] Curating this exhibition provided me with a positive answer. For example, some images of his Yanlingdui guerrillas have become an icon of China’s War of Resistance experience. What had been ignored was that those images came from Shi’s six visits to the guerrillas in three years, documenting their growth from local goose-hunters to a detachment of the Eighth Route Army. In the gallery, we displayed twenty-five photographs of this subject and juxtaposed the widely circulated ones with previously unpublished images. More are shown in the forthcoming photobook from the National Art Museum’s series, Images of China: 20th-Century Chinese Photography Masters — Shi Shaohua.

Fig. 4. Cover page of The Study of Methods of Collecting Materials for Photo-Reportage, lecture notes by Shi Shaohua. Preserved by Li Feng (1929–2016), scanned by Shi Zhimin in 2009. Courtesy of Shi Zhimin.

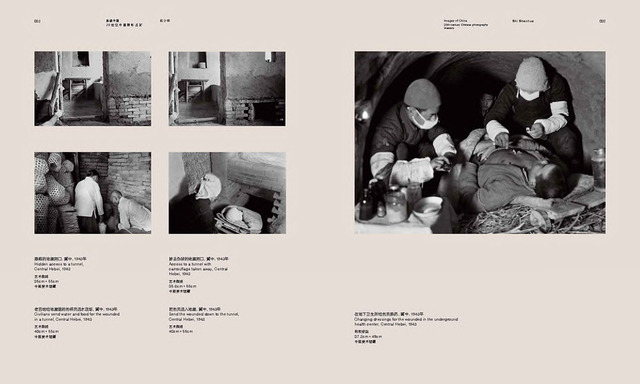

Fig. 4. Cover page of The Study of Methods of Collecting Materials for Photo-Reportage, lecture notes by Shi Shaohua. Preserved by Li Feng (1929–2016), scanned by Shi Zhimin in 2009. Courtesy of Shi Zhimin. Fig. 6. Facing pages from the photobook associated with the exhibition juxtapose a well-known image of Shi’s Tunnel Warfare (right) and previously unpublished, rarely circulated images (left). These images were on display in the exhibition. Courtesy of China Photographic Publishing House.

Fig. 6. Facing pages from the photobook associated with the exhibition juxtapose a well-known image of Shi’s Tunnel Warfare (right) and previously unpublished, rarely circulated images (left). These images were on display in the exhibition. Courtesy of China Photographic Publishing House.Chen: It’s quite well known now that Shi Shaohua organized one of the earliest photography training classes in the Communist Jin-Cha-Ji border area. Why were these classes organized and how were students selected?

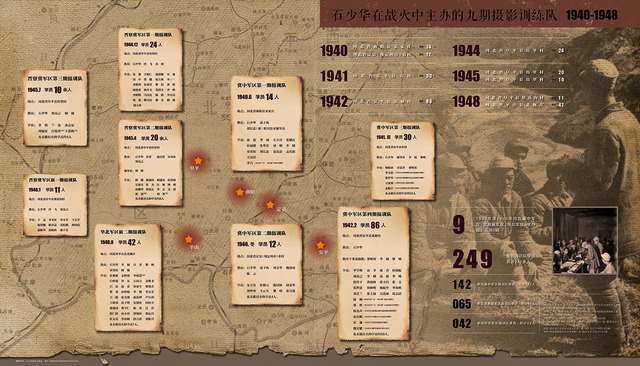

Zhou: The goal of photography training was to establish a photographic network for war mobilization at the geographically disconnected Jin-Cha-Ji border encircled by the enemy. Students were selected from various combat units and grassroots propaganda cadres. Literacy was desired but basically they were thankful for even a primary school graduate, for that counted as “intellectual” in rural North China at the time. Combat experience was another key requirement, because survival was not easy, let alone to study and work under frequent Japanese attacks and annihilation campaigns. It is interesting to note that despite the extreme scarcity of cameras, photographic supplies, and references, Shi was supported by his colleagues who taught literature, literary theory, fine art, and lighting principles to the students, in addition to Shi’s photography instruction. The program usually lasted two to three months from learning the basics through outdoor practice. After training, the students would return to their own troops to carry out photography work.

Fig. 7. A chart used in the exhibition to summarize nine photography training classes held by Shi Shaohua between 1942 and 1948 in Central and North Hebei. Class location, duration, and number and names of the faculty and students are stated in each square. Designed by Guo Meng, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.

Fig. 7. A chart used in the exhibition to summarize nine photography training classes held by Shi Shaohua between 1942 and 1948 in Central and North Hebei. Class location, duration, and number and names of the faculty and students are stated in each square. Designed by Guo Meng, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.Zhou: One significant aspect of Shi Shaohua’s manner of working was to exhaust the subject matter preordained by the Party. This is evident for many other professional photographers working for official agencies in China during the 1950s to the late 1970s. Such an approach might be considered rigid, if compared to the amateur practices toward the end of the 1970s. I think the exhibition of the Friday Salon you curated was a case in point. How did you organize materials in this exhibition?

Chen: This exhibition presented the short history of an amateur photography workshop, now known as the Friday Salon, which was conceived in the home of Chi Xiaoning (1955–2007), located in a residential compound for staff of the Beijing Film Studio, around 1977 to 1980. It demonstrated the free photography education and voluntary participation between an older generation of intellectuals and a younger generation of photography enthusiasts immediately after the Cultural Revolution.

The exhibition consisted of three main sections in two galleries. The small gallery showed works by Di Yuancang (1926–2003), Chi Xiaoning, and Zhang Lan (1948–1993), who were the key organizers of the group. Di Yuancang started teaching at Chi Xiaoning’s home in the summer of 1978 and became their main mentor. Zhang Lan was a bit older than the other students and had started practicing photography in the late 1960s. Chi Xiaoning was the one who initiated this workshop and at the time was a cinematography assistant at the Beijing Film Studio. This gallery was dedicated to three of them, to commemorate them as a great teacher and dear friends.

Fig. 8. A Home for Photography Learning: The Friday Salon, 1977–1980, Taikang Space, 2018, courtesy of Taikang Space.

Fig. 8. A Home for Photography Learning: The Friday Salon, 1977–1980, Taikang Space, 2018, courtesy of Taikang Space.The second gallery showed mainly selected works by the twenty-one members of the salon, which was divided into five categories: portraiture, landscape, xiaopin photography[3], photos showing social concerns, and experiments. Photographs and other documents of their trips to the villages and mountains on the outskirts of Beijing were also shown. The exhibit also contained many archival materials, such as Di Yuancang’s lecture manuscripts and diaries from 1977 to 1979, students’ notebooks and diaries, handmade photo albums, reference books, cameras, and examples of the enlargers and slide projectors they made during that time, all of which provided details of their practice and material conditions at the time.

Zhou: As an unofficially operated photographic study group that emerged immediately after the Cultural Revolution, I assume that both teachers and students might take different directions away from the “typical” aesthetic criteria promoted by the state. Did you discover conscious rejections or intentional distinctions from the established values in the group’s teaching and learning practices?

Chen: Absolutely. Being one of the few who introduced Western photography to Chinese readers after 1949, Di Yuancang had played a vital role in this. Before the Cultural Revolution, he had been an editor for major pictorials and photography magazines in China, such as Photography Network (sheyingwang 摄影网), Nationality Pictorial (minzu huabao 民族画报), and Chinese Photography (zhongguo sheying 中国摄影), and was an alternate member for the first council of the China Photography Society when it was established in 1956. You can find him in the first group photo of the society shown in Shi Shaohua’s exhibition. If Di’s introduction of Western photography to China before the Cultural Revolution was mainly to provide cadres with references to what had been done in the West, his voluntary teaching of a younger generation of photograph enthusiasts, around the launch of the economic reform and opening-up policy in 1978, was a way to build an alternative discourse when the situation allowed. The alternative discourse Di sought to build distanced itself from the discourse of “typicality” by bringing back the self-expressive quality of photography.

Zhou: Where did Di source his materials on foreign photography, and how did these circulate after the Cultural Revolution?

Chen: Di was assigned to work as a special-effects photographer at the Beijing Science and Education Film Studio in 1977 and he personally didn’t want to go back and work for the China Photography Society, which was in the process of resuming its operation under its new name, the China Photographers Association. However, he still had good connections with some individuals within the association, such as Wang Fatang. I think most of the materials he used for his classes at Chi Xiaoning’s home were from the society. The society had subscribed to foreign periodicals and catalogues, which were available only for internal use, some only for high-level officials. Such materials were called internal reference materials (neibu cankaoziliao 内部参考资料), and they sometimes had different-colored covers, such as gray or yellow, to differentiate levels of access. Di also asked his students to help reproduce these materials for the classes. The exhibition featured an enlarger Fan Shengping used to print such photos for Di. Lü Xiaozhong’s notebook was also full of rephotographed materials, mainly foreign photographs copied from Di’s original materials, which were on display in the exhibition too.

Zhou: What kind of foreign photography did Di teach?

Chen: Di mainly introduced works produced between the 1920s and 1970s, from European or American photographers, but also some from Japan. Sometimes he would have a class introducing one photographer. For example, one class focused on the French photographer Robert Doisneau and introduced his famous The Kiss by the Hotel de Ville (1950). Di Yuancang’s classes, being free to amateurs, were very special and extremely valuable at a time when not many books and classes were available for younger photography enthusiasts.

Zhou: What did the students think about the photography Di Yuancang taught? How was their practice influenced?

Chen: Apart from teaching Western photography, Di examined photography in a wider field of art and associated it with other national and Western art categories, such as ink painting, music, and poetry, thus expanding the students’ cultural and artistic understanding and presenting photography as a medium of self-expression. He also invited artists such as Qian Shaowu and Shao Bolin to teach fine art. Di emphasized the importance of expressing one’s feelings through photographing. Compared to the dominant style of official photography, which emphasized “typicality” largely to serve political purposes, Di’s advocacy of self-expression was new and refreshing for students who had just gone through the stifling Cultural Revolution. Their opinions and emotions were embedded in their images, through diverse styles and approaches. For example, Lü Xiaozhong’s Shidu Poplar (1978) captured the sun’s rays lighting up a poplar forest, a landscape filled with personal pleasure instead of grand mountains and rivers arousing shared patriotic feeling toward the motherland.

Compared to those of other Salon members, Chi Xiaoning’s works have a strong humanistic approach concerned with social reality and the people. He photographed the events leading up to the “April Fifth Tiananmen Incident,” in 1976, when people gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn Premier Zhou Enlai. Chi, who was standing on the Monument to the People's Heroes in the middle of the square, photographed the surging crowd from west to east, attempting to document a panoramic view of the square by collaging a series of prints together. A year later, Chi was in the square again for the first anniversary of Zhou’s death, this time with Li Tian. In contrast to Chi’s panoramic approach on the event in the square a year ago, Li took a close-up shot of the delicate flowers on the wreath laid for Zhou, which quietly depicted his lyrical expression amid a less tense public event.

On the other hand, there were photographers such as Sun Qingqing, who chose literati subjects such as bamboo and cherry blossoms, in reference to Chinese ink painting, even applying his seal to finished prints, blurring the line between photography and painting.

Zhou: Portrait photography seemed to be a popular genre among these students. I also found in the exhibition that some of the portraits indicated some visual similarity with photographs of exemplary workers, peasants, and soldiers created before the Cultural Revolution. What do you think?

Chen: The popularity of portraiture among these students could be influenced by their teacher Di Yuancang, who excelled at taking portraits and taught portrait photography at Chi’s home. Abandoning the “red, bright, and shining” (hong, guang, liang 红、光、亮) policy of the Cultural Revolution, they returned to classical lighting methods, applying different lighting ratios to express the character of the sitter. In Yu Genquan’s works, we could see he used a very dramatic dark tone to show the deep contemplation of the sitter, while in another portrait of a young actress, he used the classical bright lighting to create a pleasant feeling.

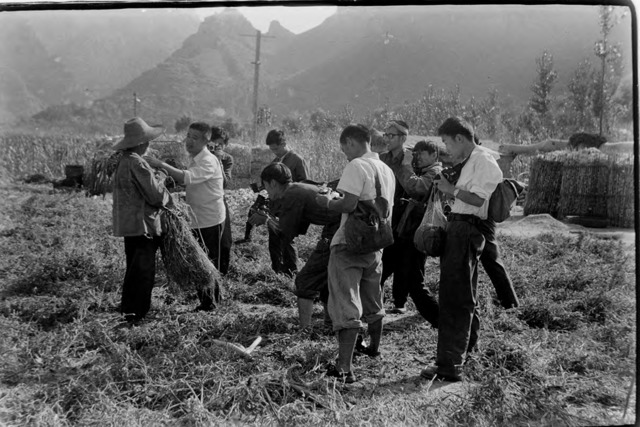

There might have been some unconscious references to the official socialist realist style. Di Yuancang’s portrait of a farmer, who was asked to pose for a photography exercise during their trip to Shidu on October 1, 1978, could be an example. Di posed this “model” farmer holding a big sheaf of harvested wheat over his shoulder in the middle of a field, surrounded by the students with their cameras in the ready position. Using a low angle to make the figure look nobler and more heroic was also a common technique for socialist realist portraiture, so I find this image intriguing, seemingly showing a paradox. From this photo, one feels socialist realist style was, to some extent, unconsciously internalized.

Fig. 16. Di Yuncang posing the farmer “model” in Shidu, Beijing, 1978. Photographed by Lü Xiaozhong, courtesy of Lü Xiaozhong.

Fig. 16. Di Yuncang posing the farmer “model” in Shidu, Beijing, 1978. Photographed by Lü Xiaozhong, courtesy of Lü Xiaozhong.Exhibitions as a Means of Circulation

Chen: In wartime China, particularly in the Communist-controlled areas, apart from training soldiers to be war journalists, images were circulated to ordinary people for purposes of propaganda. How did the CCP propagate its ideology to local people through image circulation?

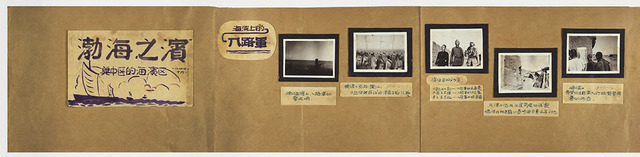

Zhou: In wartime Jin-Cha-Ji, exhibitions were a major means for image circulation at the grassroots level. And there were primarily two kinds: One was to show in public spaces, such as the bazaar, mass gatherings for holiday celebrations, military recruitment, and outdoor sporting events. The other was small-scaled mobile exhibitions, for which the troop-based photographer usually played the role of curator, designer, and “narrator.” Titles may have been given and very brief captions were added as a prompt for their interpretation. This foldable and movable format enabled the photographer to reach grassroots soldiers who were constant moving for military purposes. Both kinds of exhibitions aimed at mass mobilization, to bolster the spirit of resistance, to raise local literacy, and to spread information on the Party’s political, economic, and social agendas among soldiers, merchants, landlords, and peasants.

Shi: The photographs for exhibition in Jin-Cha-Ji were quite small. Working conditions for photographic technicians were extremely hard in wartime rural North China. They did not have electricity or running water. They usually made contact prints using sunlight. Exposure times relied entirely on experience. The small photographs were then glued onto a large piece of paper for exhibition.

Fig. 18. Part of a mobile photography exhibition entitled Bohai Seashore in Central Hebei, dated October 1944. Preserved by Gu Di, former clerk of Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial. The whole piece contains eighteen photographs, the majority of which have been identified as taken by Shi Shaohua, from his Yanlingdui series. Courtesy of Gu Di.

Fig. 18. Part of a mobile photography exhibition entitled Bohai Seashore in Central Hebei, dated October 1944. Preserved by Gu Di, former clerk of Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial. The whole piece contains eighteen photographs, the majority of which have been identified as taken by Shi Shaohua, from his Yanlingdui series. Courtesy of Gu Di.Chen: Shi Shaohua exhibited his works of the Yanlingdui Guerrillas in 1945, didn’t he?

Zhou: Yes. He recalled this in the essay about his experience at Baiyangdian Lake. It was a time when Baiyangdian was already firmly controlled by the Communists. Unfortunately, little detail was given except that the villagers were very excited to see themselves and their neighbours in photographs. This is understandable, as the camera was still a rare thing; for the local peasants, to be photographed was still an event.

Figs. 19, 20. Shi Shaohua, The Yanlingdui Detachment of the Eight Route Army in the Bohai Sea, Central Hebei, 1944. Whereas the image on the left had been widely circulated, the one on the right was published for the first time in the retrospective exhibition, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.

Figs. 19, 20. Shi Shaohua, The Yanlingdui Detachment of the Eight Route Army in the Bohai Sea, Central Hebei, 1944. Whereas the image on the left had been widely circulated, the one on the right was published for the first time in the retrospective exhibition, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.Chen: Some “typicalized” images of the Yanlingdui Guerrillas series were well circulated as his trademark. I also notice some famous stage photographs of model plays during the Cultural Revolution in the exhibition catalogue. I was surprised because I didn’t know Shi was the photographer. They might have a wider circulation and have received higher popularity than the Yanlingdui images. Do you know about the production and circulation of these stage images?

Shi: My father took the stage photographs of the model plays in 1969–70. It was a very short-term practice. In late 1968, Mao’s wife Jiang Qing encountered great difficulties in promoting the model plays through the mediums of photography and film. Suddenly she thought of my father, who had been her photography teacher. About the same time, Premier Zhou Enlai received an anonymous letter requesting the rehabilitation of Shi Shaohua. My father was then “liberated” and put in charge of the Cinema Industry Collaboration Instructing Team 电影工业协作指导小组, a completely new organ of the Cultural Group of the State Council 国务院文化组, which existed from 1970 to 1975 and functioned as the Ministry of Culture, which had earlier been dissolved. He was responsible for the recovery and improvement of industrial research and production into film and photography. In 1970 he became too busy with various cultural activities and foreign affairs and the assignment was passed to other photographers in the Xinhua News Agency.

Chen: In the exhibition catalogue, I saw a stage photograph taken by Shi in 1942, for the famous play Sunrise. It would be interesting to compare this with his photographs of the model plays.

Shi: The most significant difference between the two is not the shooting style, but rather the subject, the style of theatrical performance. If we use the same shooting angle to take a still of two model plays, Chicago and Cats, for example, the visual results will definitely be different. The photographer is not the play’s director, and a still is a faithful presentation of the performance, rather than a subjective creation. The heroes in the model play are meant to be gao (高, lofty), da (大, glorious), and quan (全, complete). That leaves very limited space for a photographer’s creation.

Fig. 21 (left). Shi Shaohua, stage photograph of Sunrise performed by the Front Line Troupe 火线剧社, Central Hebei, 1941, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.Fig. 22 (right). Shi Shaohua, stage photograph of the revolutionary Peking opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, Beijing, 1970, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.

Fig. 21 (left). Shi Shaohua, stage photograph of Sunrise performed by the Front Line Troupe 火线剧社, Central Hebei, 1941, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.Fig. 22 (right). Shi Shaohua, stage photograph of the revolutionary Peking opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, Beijing, 1970, courtesy of Shi Zhimin.Zhou: The production and circulation of Shi Shaohua’s work was officially approved and opened to a public audience from the very beginning. By contrast, the production and circulation of the works by the Friday Salon was private, independent, and based on close interpersonal relationships. What kinds of exhibitions did they carry out?

Chen: If holding exhibitions was an efficient way to circulate images for political purposes, it was also an efficient way to circulate images for knowledge sharing. Holding informal photo-sharing sessions and internal exhibitions were important methods for the Friday Salon to discuss their own works and learn from one another. The only internal exhibition was held on the night of January 12, 1979. At a time when few public institutions hosted exhibitions for nonofficial amateur art practice, a private home remained the perfect venue. Each student contributed five or six works for this exhibition. Photos were pinned on thin strings hung on the walls in the living room of Chi’s home. Unfortunately, no images of the exhibition appear to have been taken, apparently due to the dim lighting.

In the Friday Salon exhibition, some of the photos were presented in the same format as this internal exhibition of 1979 — pinned to wires on the wall — in order to partially re-create this scene, further contextualized by exhibiting furniture from the 1970s, to re-create a homelike space.

Zhou: Did Wang Zhiping and Li Xiaobin, the cofounders of the April Photo Society, discover the works of the Friday Salon through this internal exhibition at Chi Xiaoning’s home?

Chen: Yes. When Wang Zhiping and Li Xiaobin were looking for more participants for the first April Photo Society exhibition, Nature, Society, and Man, Li learned from Chi Xiaoning that there would be an internal exhibition held at his home. Wang and Li went to see it and invited Salon members to be part of their show. Most members of the Friday Salon participated in the Nature, Society, and Man exhibitions between 1979 and 1981, and by joining the April Photo Society,[4] the Friday Salon was able to emerge from a private to a public space. In this way, their photographs were circulated not just among themselves but also in public.

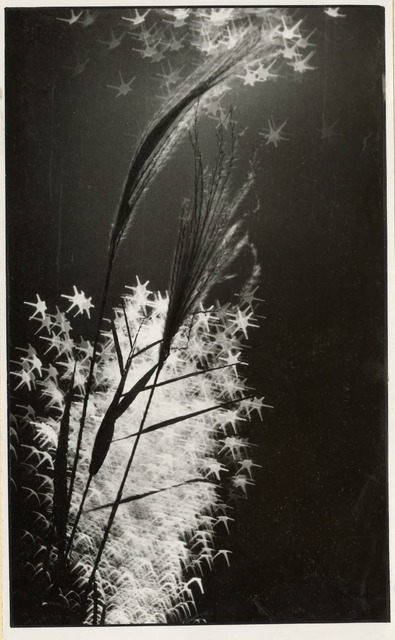

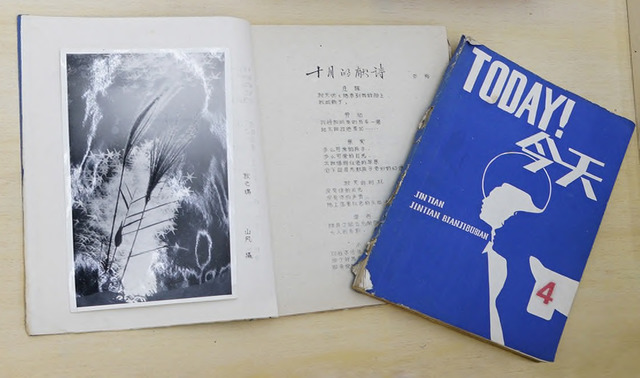

After the launch of the economic reform and opening-up policy, more and more informal art groups emerged in Beijing, such as the poetry magazine Today and the Stars group. There were personal connections between some key members of these groups. For example, Chi Xiaoning was a friend of Bei Dao, a founding member of Today, and of Huang Rui, a founding member of both Today and the Stars. Photographs were circulated within this personal network too. For example, Zhang Lan’s The Soul of Autumn — picturing two reeds against sparkling water — was first shown in the Friday Salon’s internal exhibition, but it was soon featured in the second issue of Today (February 1979), published under the pseudonym “Shan Feng.” In its fourth issue, in June 1979, Zhang wrote a review of his own photo, this time using the pseudonym “Gong Chang.” The Soul of Autumn was exhibited in the first Nature, Society, and Man, in April 1979, too.

Fig. 23. Zhang Lan’s The Soul of Autumn (fig. 23) was first published in the second issue of Today magazine; in the fourth issue, in 1979, an article reviewed this photo (fig. 24). Courtesy of Cheng Xin.

Fig. 23. Zhang Lan’s The Soul of Autumn (fig. 23) was first published in the second issue of Today magazine; in the fourth issue, in 1979, an article reviewed this photo (fig. 24). Courtesy of Cheng Xin. Fig. 24. Zhang Lan’s The Soul of Autumn (fig. 23) was first published in the second issue of Today magazine; in the fourth issue, in 1979, an article reviewed this photo (fig. 24). Courtesy of Cheng Xin.

Fig. 24. Zhang Lan’s The Soul of Autumn (fig. 23) was first published in the second issue of Today magazine; in the fourth issue, in 1979, an article reviewed this photo (fig. 24). Courtesy of Cheng Xin.Issues of Current Research in the Field of Photography History in China

Zhou: Over the past decade, scholars who have taken photography in China as an object of study have first had to confront the scarcity of primary sources. Our exhibitions were no exceptions. What challenges did you face?

Chen: The availability of archival materials is vital for any historical research, and accordingly the lack of research on the Friday Salon has largely been the result of the unavailability of such materials; it has been mentioned only as part of the April Photo Society. In the course of my doctoral research, I spent the first four years traveling to Beijing at least once or twice a year, to conduct interviews with Friday Salon members and collect materials directly from them.

Chen: Zhimin, given that Shi Shaohua is your father, have you had better access to his archival materials?

Shi: A bit better — at least I know where to look for his materials. All the photographs and documentary materials in the retrospective exhibition came from our private collection, a self-funded project started around 2005. We collect works, writings, and activities by Shi Shaohua as well as resources about the photographic publications and agencies with which he was associated. I’ve worked primarily on collecting and digitalizing prints, negatives, and documentary materials. Dengyan joined in 2005 and tried to categorize and research the digitalized materials. Part of our collection came from my father’s study and part from auctions, secondhand bookstores, my father’s former colleagues, and institutional archives. I understand more about my father through this archiving process. After visiting the exhibition, many professional audience members expressed that they didn’t know Shi was such a productive photographer.

Zhou: Another time-consuming job for us was the composing and editing of Shi’s biography. Shi didn’t leave many autobiographical texts, and information about his activities during the Cultural Revolution is extremely rare. The exhibited biography was a result of painstakingly weaving together scattered sources from newspapers, magazines, books, memoirs, original interviews, and various kinds of internally circulated material. Through this process, we were also able to correct factual mistakes and assess anecdotal evidence in previous literature, which I think will be useful for further studies.

The present exhibition manifested Shi’s contribution to the Chinese collective memory of national independence and socialist revolution in visual form. But his role as an indigenous theorist of photography and a chief executive of the national photographic network in Mao’s era has yet to be fully explored. The difficulty lies mostly in the accessibility of new archival resources. For example, most of his post-1949 photographic works were archived in the Xinhua News Agency, where he served as the director of its photography department for about three decades and as its vice president for two decades. However, neither his unpublished photographic works nor his “file” (dang’an, a permanent dossier recording his career performance and political attitudes) is allowed to be seen, even when requested by his sons. Researchers currently have to rely on publications and original interviews with his former colleagues. When this institutional archive might open to the public remains unknown, but we believe that the accessibility of new archival resources would deepen our understanding not only of this photographer, but also of photography and history in Mao’s China.

Chen: It’s interesting to consider such difficulty researching even prominent figures like Shi Shuahua, whose dang’an is classified by the state, even though the interest in his works and life is relatively high. Comparatively, interest in the Friday Salon is lacking in part because of the general lack of recognition for the value of amateur practice in China. I feel that researchers have often been trapped in a convention of researching big-name artists, so interest in the less spectacular but still historically significant events has remained minimal. I think this tendency relates to a lack of interdisciplinarity in the field of photography history in China.

I’m interested in how friendship and intergenerational support helped form “home study workshops” — a unique social phenomenon that emerged around the mid-1970s — which created an alternative and promising career path that they proactively sought for themselves. Photography, for the members of the Friday Salon, was a technique to master for a better future when opportunities were often doomed due to their “black” family backgrounds.[5]

Beyond individual collecting and research, institutional support is very important for the young but growing field of photography history in China. In my case, Taikang Space’s continuing interest in scholarly research on Chinese photography history has provided a solid and supportive institutional platform to bring such research to the public.

Zhou: I strongly agree! The appearance of these two exhibitions in Beijing points to two emerging but important engagements in contemporary curatorial practice in China. First, there’s a conscious consensus of independent curators and institutional agents returning to a history of Chinese photography in its own right. Although these two exhibitions focused on two distinctive historical moments, they shared the idea of taking a turning point in the history of photography in China as a lever to interrogate broader established historical narratives and assumptions. Second, the relationship between independent researchers and art institutions is closer than ever, but at the same time provisional and unstable, in collecting and studying photography in China. I have to admit that without an official sponsor, our decade-long research on Shi Shaohua would not have had the opportunity to be shown to the public in the form of a photographic exhibition.[6] Of course, negotiation and compromise accompanied the entire curating process, most obvious in the extremely short exhibition period and the displacement of Chairman Mao’s image for the exhibition poster. But constraint made the curatorial experience more challenging and interesting, didn’t it? Given the fact that a public museum dedicated to photography has yet to come in China, I believe such exhibitions help draw institutional attention to the archiving and researching of photography and history in China.

Authors’ Note: The authors would like to thank Olivier Krischer for his useful comments and encouragement.

Chen Shuxia is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University, with a research focus on Chinese photography and artist groups in China. She was the recipient of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Greater China Research grant 2014. Chen is the Curator of China Gallery, the Chau Chak Wing Museum, the University of Sydney. Contact: [email protected]

Zhou Dengyan is an assistant professor at Beijing Film Academy. She holds a PhD in Art History from Binghamton University. Her writings have appeared in Trans Asia Photography Review, photographies, British Art Studies, OSMOS, Chinese Photographers and other journals. She is also the editor of Quanguo sheying yishu zhanlan bangongshi koushu shiliao ji [A History of “The National Photographic Art Exhibition Office”: Reminiscences and Documentary Materials 1972–1978] (Hong Kong: Shanghai Press, 2015). Contact: [email protected]

Shi Zhimin is an independent photographer, curator, and photographic historian. He received an MFA in photography from Brooklyn College in 1991 and has recently focused on Chinese photography archiving. One of his publications is the three-volume Jin-Cha-Ji huabao wenxian quanji [A Comprehensive Documentary Collection of Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial] (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe, 2015). Contact: [email protected]

Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial was the first photographic magazine published by the Communist Party in the Jin-Cha-Ji border region of rural North China. From its founding in 1942 to its expansion and renaming as North China Pictorial in 1948, the Pictorial functioned not only as the Party’s most important photographic agency of wartime mobilization, but also, and more significantly, as a crucial actor in shaping new conceptions of pictorial realism and new regulations of photographic practice. For an archival reproduction of the Pictorial, see Shi, Zhimin ed., “Jin-Cha-Ji huabao wenxian quanji” [A Comprehensive Documentary Collection of the Jin-Cha-Ji Pictorial], volumes 1, 2, and 3 (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe, 2015). For a discussion of the Pictorial and the shaping of the CCP’s photography network, see Zhou, Dengyan, “The Language of “Photography,” in China: A Genealogy of Conceptual Frames from Sheying to Xinwen Sheying and Sheying Yishu (PhD diss., Art History Department, Binghamton University, 2016), 80–111.

For a detailed examination of Shi’s theory of “the typical,” see Zhou, Dengyan, “Shi Shaohua de sheying shijian: 1932–1945 nian de chuangzuo yu lilun tansuo” [Shi Shaohua and His Photographic Practice: Practical and Theoretical Experimentation Between 1932 and 1945], Zhongguo sheying jia [Chinese Photographers], no. 9 (2018), 60–69.

Xiaopin means little or short work in literature, theater, ink painting, and photography, for works that are informal, spontaneous, interesting, compared to grander narratives. See Chen, Shuxia, “Departing from Socialist Realism: April Photo Society, 1979–1981,” in Tap Review 1 (2017). Accessed 2 February 2018. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0008.103/—departing-from-socialist-realism-april-photo-society-1979?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

April Photo Society was an amateur photography group that was active from 1979 to 1981 in Beijing. The group annually held an exhibition titled Nature, Society, and Man — the first few public photo exhibitions held by unofficial photography practitioners. See Chen, Shuxia, “Departing from Socialist Realism: April Photo Society, 1979–1981,” in Tap Review 1 (2017). Accessed 2 February 2018. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0008.103/—departing-from-socialist-realism-april-photo-society-1979?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

Mao Zedong categorized five groups of people as enemies of the Cultural Revolution. They were landlords, rich farmers, counterrevolutionaries, bad influencers, and the rightists. Parents of most members of the Friday Salon were intellectuals and some of them were labeled as rightists.

This exhibition was incorporated into the National Art Museum’s National Art Collection and Donation program, and was sponsored by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.