Rerouting the Modernist Visions of Horino Masao: Territorial Photography, Mass Amateurism, and Imperial Tourism

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In early 1938, the modernist photographer Horino Masao (1907–1998) embarked on a journey through Korea, then in its twenty-eighth year under Japan’s colonial rule. He thus joined a school of filmmakers, artists, and novelists who enlisted their expertise to the imperial project of visualizing Japan’s expanding territories. Horino’s trip was sponsored by the Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea, which promptly used some of his photographs for its booklets promoting imperial tourism: Impressions of Korea / Chōsen no inshō, published in March 1938, and Recent Photographs of Korean Peninsula / Hantō no kinei, published in April 1938. The following summer, he undertook another colonial voyage through areas of China that were under Japanese control. The sponsors this time were a consortium of Japanese imperial transit authorities: Mantetsu (South Manchurian Railway Company), Central China Railways, and North China Transport.

The resulting photographs attest to multiple modes of mobility that characterized photography in the era of mass communication: the mobility of Japanese intelligentsia in the colonial spaces; the mobility of photographs that were disseminated to international news services as anonymous stock images; and the mobility of modernist photographers whose output could not be contained in traditional domains of the salons, photographic magazines, and gallery exhibitions. One of the features that defined interwar modernist photography was a non-hierarchical comparison of artistic works and anonymous “practical” photographs made for medicine, advertisement, and journalism. Not surprisingly, therefore, some of the images that were disseminated anonymously as stock images of Korea also appeared in photography books published under Horino’s name.

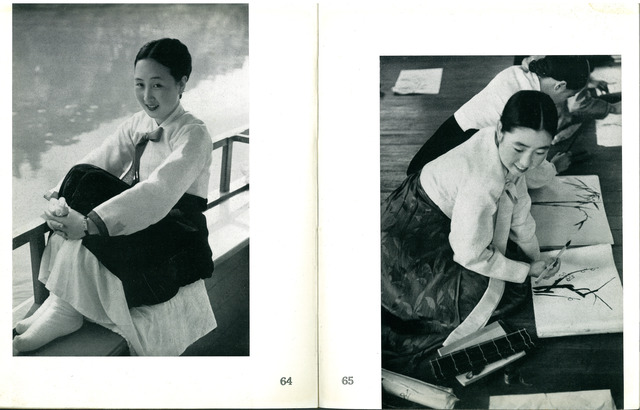

Take the photograph that shows two young women, dressed in a simple Korean dress (chima jeogori), practicing ink painting of the classical floral repertoire. The image was reproduced in multiple publications, among them Horino’s glossy monograph, Elegance of Women / Josei-bi no utsushikata (figure 1), the tourism booklet Impressions of Korea (figure 2), and the photography magazine Camera. Elegance of Women, which was published in October 1938, introduced techniques for capturing modern sensibilities embodied by one hundred female models of various ethnicities. The photograph in question appeared in a double-spread diptych alongside a portrait of another Korean woman, this one seated on a bench by a river. The glossy paper brings out subtle details, such as the elegant watch that gives a modern touch to the otherwise traditionally dressed sitter by the water, and the floral pattern woven into the fabric of the skirt worn by the painter. Also visible is the rich gradation of gray, which reveals the photographer’s attentive care to capture the gentle sunlight that bounces off the river and highlights the contours of the sitter.

Fig. 1. Horino, Masao, from Elegance of Women / Josei-bi no utsushikata,1938, Tokyo: Shinchōsha, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.

Fig. 1. Horino, Masao, from Elegance of Women / Josei-bi no utsushikata,1938, Tokyo: Shinchōsha, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao. Fig. 2. Uncredited, from Impressions of Korea / Chōsen no inshō, 1938, Osaka: Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea.

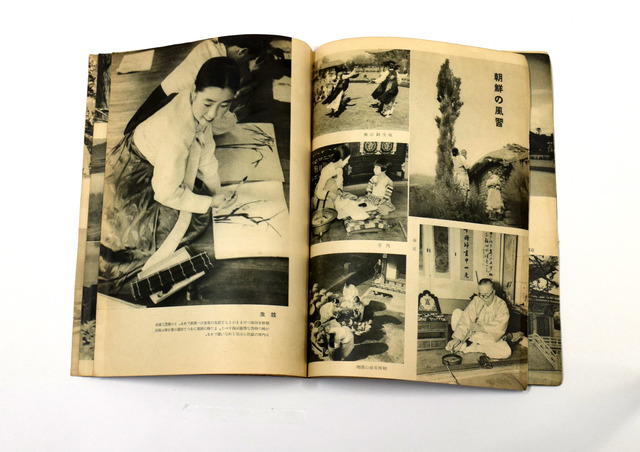

Fig. 2. Uncredited, from Impressions of Korea / Chōsen no inshō, 1938, Osaka: Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea.All such details are lost in Impressions of Korea, a mass-disseminated booklet in which the same photograph appears in a different cropping and printed on coarse paper. In the booklet, the same photograph is incorporated into a section titled “Korean customs” (chōsen no fūshū) alongside photographs displaying colonial clichés: young female entertainers performing a sword dance, a group of women gathered in a communal courtyard to make kimchi (Korean pickles), and a patriarch posing with a traditional long pipe. The photographs appear to showcase standardized scenes expected in imperial tourism.

If Elegance of Women approached modernity as a quality embodied by the subject matter, Impressions of Korea put into practice the modern promise of mass communication, of disseminating the tourist views detached from artistic intentions.

The comparison of the two contexts serves to remind us of the complex ways in which imperialism informed the development of modernist photography. Horino’s colonial voyages were one small part of the much broader dynamic that Louise Young calls a “total” form of empire building that entailed “the mass and multidimensional mobilization of domestic society: cultural, military, political, and economic.”[1] Colonial tourism had a particularly productive role in this shift, not simply by bringing Japanese intelligentsia to the colonies, but also, and more importantly, by stabilizing the otherwise incoherent spatial relation between Japan proper and the newly gained territories of Taiwan (1895–1945), Korea (1910–45), and Manchuria (1932–45).[2] By the late 1930s, tourism propaganda had become an unlikely site for modernist photographers’ experimentation. There are a few privileged examples that have generated robust discussions on this issue, such as the illustrated magazine Nippon (1934–44), produced by the collective Nippon Kōbō with Natori Yōnosuke as the editor in chief, and the colossal photo-mural Tourism Japan / Kanko Nippon, by the Bauhaus-trained designer Yamamura Iwao, exhibited at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939.[3] These examples attest to the effective ways in which the language of modernist photography was mobilized to disseminate imperial propaganda. By contrast, Horino Masao’s oeuvre demonstrates the ways in which imperial geography had already informed modernist experimentation. In the following discussion, I seek to dislocate the conventional narrative of Horino’s oeuvre, which tends to emphasize the internal logic of the artist’s modernist vision as it developed over the course of his career. Instead, this paper provides a remapping of Horino’s modernity centering on three interrelated aspects of imperial geography: expansion of colonial territories, rationalization of territories as tourist destinations, and redrawing of professional boundaries.

Rerouting the Modernist Vision of Horino Masao

In the past few decades, critical and popular interest in Horino Masao has been on the rise, helped by the improved accessibility of his critical essays and representative monographs, such as Artistic Theories of Contemporary Photography (Gendai shashin geijutsuron, 1930, reprinted in 1991) and Camera, Eye x Steel, Construction (1931, reprinted in 2005). To complete the process of putting Horino back on the map, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography held a major retrospective, titled Vision of the Modernist: The Universe of Photography of Horino Masao (March 6–May 6, 2012), which showcased 150 items divided into six phases of Horino’s short artistic career, from 1925 to 1939.[4]

As is the case with maps in general, that of interwar Japanese photography is structured around fixed coordinates: the stylistic opposition of Art Photography (geijutsushashin) and New Photography (shinkōshashin) on the one hand and the paradigm shift from an understanding of photographs as works to be exhibited in galleries to a reconceptualization of photographic images as a means of mass communication.[5] This is evident in Iizawa Kotaro’s 1991 essay, “Photography That Opens Up to Society: Pioneerism of Horino Masao,” which introduces a symbolic anecdote of young Horino sitting outside the Marunouchi Building (a large modern office building in central Tokyo) in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, selling self-printed photographs of iconic buildings.[6] The entrepreneurial efforts of directly selling the photographs in public marked a stark departure from amateur art photographers’ distinctly middle-class preference for peer-to-peer evaluation.[7] The episode embodied the spirit of the New Photography movement avant la lettre, prefiguring the charter of the International Photography Association (Kokusai Koga Kyokai, founded in 1929), objecting to separating “the film and the photograph from real society,” and the critic Ina Nobuo’s essay that urged photographers to “return to photography” in the New Photography movement’s de facto flagship journal, Koga (1932–33).[8]

The curator Kaneko Ryuichi expands on Iizawa’s observations in the catalogue essay accompanying the 2012 exhibition, but breaks down Horino’s objection to Art Photography’s premise of photography-as-art into two phases: the experimental phase (circa 1924–32) and the practical phase (circa 1932–45). The experimental phase centered on exploring new ways to see the world through what the German critic Franz Roh called the photo-eye.[9] Not unlike Roh’s collaboration with the typographer Jan Tschichold, which resulted in the influential book Foto-Auge, Horino worked closely with Itagaki Takao (1894–1966), an influential art critic who led an aesthetic movement popularly known as Kikaiha, or the Machinist School, which resulted in his breakthrough monograph, Camera, Eye x Steel, Composition (1932).

On the one hand, it is easy to see the imprint of Moholy-Nagy and other European modernists in Horino’s early works. In fact, he was involved in organizing the International Traveling Photography Exhibition from Germany (Doitsu kokusai idō shashin-ten) (Tokyo, April 13–22, 1931, and Osaka, July 1–7, 1931), scaled-down version of the International Exhibition of the German Industrial Confederation: Film and Photo, a milestone showcase of Soviet Constructivist design and the German New Vision movement led by László Moholy-Nagy, Frantz Roh, and Albert Renger-Patzsch, which had been held originally in Stuttgart in May 1929.[10] On the other hand, instead of being awestruck by the exhibition that gave the Japanese public the rare chance to see the original prints of leading European photographers alongside anonymous posters, medical and scientific photographs, and industrial designs, Horino observed the disappointing technical flaws in the work of Moholy-Nagy and his associates that he could see vividly in the original prints.[11] In Kaneko’s overview, this was not so much a criticism of Moholy-Nagy as it was a recognition that modern photography was meant to be seen in mass-reproduced print media rather than as original prints exhibited on gallery walls. This marks the transition from the experimental stage to the practical stage in Horino’s pursuit of photography’s modernity.

Kaneko locates the turning point in Horino’s oeuvre from the experimental to the practical stages in the period between October 1931 and December 1932, during which he published a dozen “graph-montage” projects in monthly magazines such as Chuo koron and Hanzai kagaku. For each project, Horino combined photographs and typographic texts spread across ten to twenty pages that gave concrete expressions to general themes such as Great Tokyo, Sumida River, and Life on the Water. In terms of appearance, “graph-montage” was a mix of photo-montage, an assemblage of multiple photographs on the single plane, and reportage photography, a form of storytelling that arranged images and texts across multiple pages. In terms of intellectual grounding, it was a cross-fertilization of New Photography’s reinterpretation of photography as a representative medium for the age of mass communication on the one hand and Social Realist interests in recording the lives of the proletariats and the sub-proletariats on the other.[12] This ambiguous ideological basis can be seen reflected in the names of critics, artists, and poets who contributed the “scenarios” for the eleven sets of graph-montage, which included the aforementioned critic Itagaki Takao, the influential theorist of mass communication Ōya Sōichi (1900–1970), and the leftist artist and theorist Murayama Tomoyoshi (1901–1977).[13]

If New Photography articulated the objection to the separation of photography and society, graph-montage pointed to practical ways of reconciling the two. It was important that graph-montage projects were addressed to mass readership via illustrated monthly magazines rather than to specialized readership via photography journals. During this period, Horino signed a part-time contract (shokutaku) with Fujingahōsha, the renowned publisher of Japan’s oldest women’s lifestyle magazine. Another key factor that made graph-montage a pivot point is Horino’s adoption of the Leica in 1932. The celebrated German small-size camera has been credited with giving professional photographers improved mobility, thus contributing to the rise of a new class of freelance photographers who would embark on long journeys for extended periods of time. Taken together, Horino’s gravitation toward monthly magazines and the use of the Leica signaled modernist photographers’ migration from the domain of galleries and photography journals to the domain of reportage photographers (hōdōshashinka) — a term Natori Yonosuke popularized on his return to Japan from Germany in 1933.

What is downplayed in Kaneko’s summary, however, is the geographical reorientation that informed this turning point. Instead of neatly mapping Horino’s works onto the existing molds of photographic history, can we open them up to the dynamic remapping of geopolitical landscapes, class relations, and professional boundaries in the turbulent decade of the 1930s?

Counter-Territorial Photography: Graph-Montage “Tamagawa-beri” (1932)

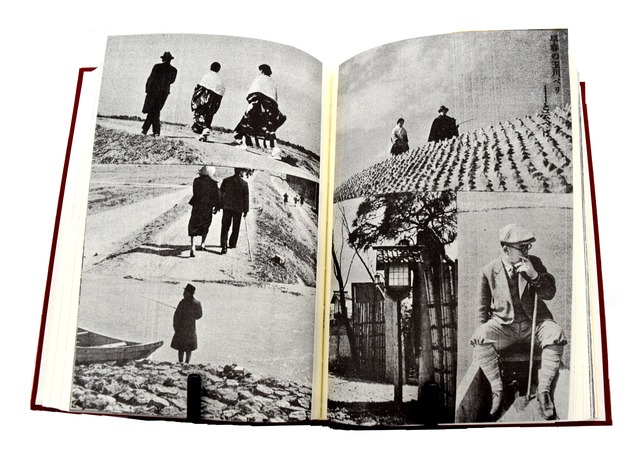

Is it simply coincidence that Korean laborers were the central theme explored in the graph-montage project Tamagawa-beri (or By the Tama River), which was a pivotal work that marked the beginning of Horino’s Leica phase, or what Kaneko called the “practical phase” in his modernist program? Published in the April–May 1932 issue of Hanzai kagaku, Tamagawa-beri consisted of forty-one pictures spread across twenty pages that provided a multilayered look at the Tama River (present-day Chōfu, in suburban Tokyo). The first four pages establish the Tama River as a typical space of bourgeois excursion: two elegantly dressed women promenading with a suited man, a pair of couples in a rowboat, and a woman with a fur shawl sitting in a taxi (figure 3). The images responded to the inlaid text on the first page, which read: “Early spring on the Tama River reminds us of . . . ” In a sense, these images functioned like an advertisement for the Leica, in that they mimic the kinds of photographs the urban affluent class might shoot with a high-end camera.[14]

Fig. 3. Kitagawa, Fuyuhiko and Masao Horino, details of Tamagawa-beri, Hanzai kagaku vol. 3. no. 6, May 1932, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.

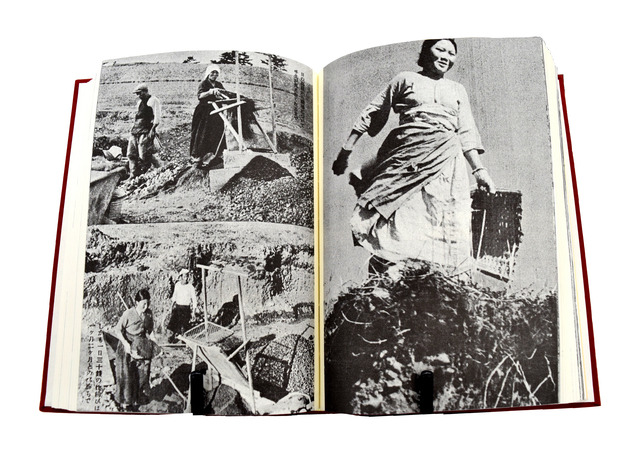

Fig. 3. Kitagawa, Fuyuhiko and Masao Horino, details of Tamagawa-beri, Hanzai kagaku vol. 3. no. 6, May 1932, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.Yet things are not what they seem. In keeping with the conventions of city symphony films and street films, Horino portrays an urban landscape that is visibly stratified. From the fifth page, the bourgeois landscape gives way to a site of labor (figure 4). The shift is announced by another text: “But there is another world here” and, further, “Koreans and Japanese [naichijin] cheerfully work together.” The introduction of Korean laborers marks the stylistic shift from hobby photographers’ sketches of the everyday to a journalistic investigation of reportage photography. The low-angle shot of a female laborer gives us an embodied sense of the photographer’s position in the landscape. The obtrusive presence of the dirt and the grass in the foreground, which takes up almost a third of the pictorial plane, gives the photograph a sense of urgency, as if this was a news photograph shot from inside the trenches. Unlike reportage photography, however, graph-montages give abstract impressions rather than concrete information.

In a smaller photograph on the subsequent page, a different female laborer stares blankly at the camera, sparking a series of unanswerable questions regarding her life, her feelings, and the power relations between the photographer and the subject. The written scenario provided by Kitagawa Fuyuhiko, a Manchuria-born leftist poet-cum-critic, overcompensates for the barred emotional access with excessive detail: They work from sunrise to sunset, on a meager daily wage of thirty sen (for a point of comparison, an issue of the magazine Hanzai kagaku was priced at sixty sen), which is often paid two months late.[15]

Fig. 4. Kitagawa, Fuyuhiko and Masao Horino, details of Tamagawa-beri, Hanzai kagaku vol. 3. no. 6, May 1932, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.

Fig. 4. Kitagawa, Fuyuhiko and Masao Horino, details of Tamagawa-beri, Hanzai kagaku vol. 3. no. 6, May 1932, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.Even though Tamagawa-beri was shot within Japan proper, it is apt to treat it as a study of imperial geography — that is to say, an organization of space in which the macro-level movement of Korean migrant laborers intersected with the micro-level movement of the urban middle class. Ultimately, Tamagawa-beri captures a dynamic landscape that is literally being transformed by the hand of colonial laborers, which in turn carves out a professional domain for reportage photographers that is cordoned off from the domain of hobby photographers.

The work of photographing a physical territory is often bound up with the rationalization of photographers’ professional territory. As Joel Snyder’s seminal study of mid-nineteenth-century American landscape photography suggests, “territorial photography” is suspended between two traditions: that of “American picturesque-sublime,” in which photography legitimizes a developer’s gaze that sees the American West as both “unspoiled innocence and an opportunity to profit from the violence of innocence,” on the one hand, and that of scientific photography, which legitimizes a rationalized technocratic gaze that “mark[s] off” the terrain as inaccessible to the public except by expert skills.[16]

Tamagawa-beri operates between these territorial claims; it registers an internal frontier where Japanese and Korean laborers work side by side to literally transform the land, but it also exercises a rationalized technocratic gaze that marks off various territories for different modes of seeing. It is significant in this context that all but one of Horino’s photo-montages were published in Hanzai kagaku (literally “Crime Science”), for which he held a position of photographer in residence with monthly assignments.[17] Promoted as an “encyclopedia of crime stories,” Hanzai kagaku strategically confused the hierarchy of news items, intermixing racy crime stories and sex journalism with features on the colonies.

If the enbon (yen-book) boom in the late 1920s expanded the reading public with drastically reduced pricing for novels, the emphasis in the 1930s was more about reconfiguration, as this was a time when newspapers, magazines, and the radio competed to provide mass communication following the Mukden Incident, or the Japanese Imperial Army’s self-orchestrated “assault” that catalyzed the occupation of Manchuria in September 1931.[18] For instance, subscribers to Hanzai kagaku would have encountered the Korean laborers in Tamagawa-beri in the opening pages of the May 1, 1932, issue, right after the article “Only 50 yen for a Round Trip: A New World of Manchuria-Mongolia” (Tatta 50-en de ōfuku: shintenchi Man-mō e), which closed the April 15, 1932, special issue on Manchuria and Mongolia. Although it is doubtful that readers would have used this article literally to plan a Manchuria-Mongolia journey given that most such trips were planned by groups (schools, companies, and cultural associations) rather than individuals, it was nevertheless presented as a realistic possibility as fifty yen, roughly a month’s wage for young middle-class professionals, would have been within the horizon of possibility for some readers.[19]

Snyder’s concept of territorial photography actually applies in an inverse way to Horino’s case. In Snyder’s study, Timothy O’Sullivan’s “astonishing, often alienating, at times gruesome” depiction of the American West is interpreted as a gesture that claims the land as an exclusive territory reserved for “modern science and its attendant professionals.” To quote his expression:

[This] marked the beginning of an era — one in which we still live — in which expert skills provide the sole means of access to what was once held to be part of our common inheritance.[20]

In Horino’s case, however, the territorial claim does not derive from the concerns of separating specialist photographic knowledge from common forms of knowledge; it derives instead from the ethos of totalizing, that is to say, of prioritizing rationalization at the cost of skilled professionals’ territorial interests. Take, for example, his 1934 essay reflecting on his fifth solo exhibition, which showcased his studies using the Leica. In addition to the expected mentions of what one could do with it — taking intimate shots of urban subjects without arousing suspicion or flexibly making enlargements from customized 35 mm film adapted from cine-film — he astutely positions the Leica’s technical innovations in the broader context of what he calls “Kodak work”: that is, the rationalization of photography by means of taking skills away from the hands of consumer-photographers. In practical terms, he urges the readers to outsource laboratory work and embrace a division of labor. On the surface, Horino’s essay was consistent with his previous position in critiquing accomplished amateur photographers’ tendency to privilege expertise and artisanal control over the entire process of shooting, developing, and printing their works.

Paradoxically, however, by aggressively pushing for a rationalization of photography, Horino carved out a professional territory for himself as the spokesperson of the silent class of photographers that we might call mass amateurs (amateur photographers who are defined more by their use of mass-disseminated photographic magazines rather than by regional camera clubs).

Colonial voyages further bolstered Horino’s counter-territorial interventions to usurp the roles traditionally played by amateur masters, namely, of publishing technical guides aimed at mass amateurs.[21] Upon his return from colonial journeys, he published books such as Correct Exposure and Photographing / Tadashii roshutsu to utshikata (July 1938), My Photographic Techniques / Watashi no shashinjutsu (September 1939), and The First Step in Leica / Raika no dai-ippo (May 1940). In The First Step in Leica, for example, he excoriates amateur masters who are “trained in greenhouse environments” who busily apply themselves to visualize preconceived ideas with carefully selected equipment, staying safely within their specialized fields. Although his critique of amateur masters for misguiding the rest of the amateur class was consistent with New Photography’s repudiation of Art Photography in the early 1930s, it was now presented as a populist voice fully backed by the culture of mass mobilization. For example, he follows up on the seemingly oppositional advice that more photographers venture out of Japan if only to experience the technological superiority of German and American film over inferior Japanese domestic brands with a sharp criticism of “amateur leaders who blindly praise domestic products.”[22]

Imperial Tourism: The Kisaeng School

The confluence of imperial geography and rationalization of photography that I have explored above found a fuller expression in Horino’s journeys in the colonies. Although this is not the right place to discuss the richly intertwined histories of modern tourism and imperialism in Japan, it is helpful to make two general observations. The first has to do with the highly politicized origin of Thomas Cook–style mass tourism in the country, which took the form of Asahi Shimbun’s “Korea-Manchuria Tour” (Senman-shuyu) in 1908 and rode the wave of patriotic sentiment invested in the battle sites of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).[23] To be sure, it was the business of attracting Western visitors to Japan for financial and diplomatic purposes that motivated the foundation of governmental and civil institutions such as the Japan Tourism Bureau (1912–41), the Board of Tourist Industry (1930–42), and KBS (the predecessor to the Japan Foundation, 1934–72). By the 1930s, however, the Japan Tourism Bureau had a growing network of offices in Manchuria and the Board of Tourist Industry sponsored promotional films, poster campaigns, and photography contests that sought to bolster the Japanese interest in visiting the colonies.

The second observation has to do with the significant roles photographic media played in democratizing the tourist gaze, enabling the masses to attain the vantage point of imperial tourists. Given that neither international nor domestic legal structures could permanently and consistently define the relationship between Japan proper and the newly gained territories of Taiwan (1895–1945), Korea (1910–45), and Manchukuo (1932–45), the task of making the “empire” imaginable as a coherent whole fell on the intellectuals and the cultural workers.[24] In a creative solution to bolster the propaganda campaign in the wake of the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, in the summer of 1937, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs actively solicited amateur photographers for images to be disseminated to international press agencies.[25] Articles in photographic magazines soon started to question the conventional boundary between the professional and the amateur in wartime. The New Photography pioneer Kanamaru Shigene, for example, excoriated professional photographers who passed blanket judgments on amateur photographers, defending the latter for their potential to produce socially conscious works (shakaisei o motsu shashin sakuhin) and calling on the government to provide guidance for them rather than suppress their expressions.[26]

This returns us to the images of the young Korean women with which I opened this essay, although this time my focus will be on the sociohistorical contexts surrounding the subject matter: the Kisaeng. Contemporary tourism brochures described the Kisaeng as the equivalent of Japan’s Geisha. As scholars have pointed out, there is a parallel between the Western gaze on the Geisha and the Japanese gaze on the Kisaeng, both of which function as abstract gendered signifiers of colonial hierarchical relations.[27] Drinking with Kisaeng was not only a popular activity for male Japanese tourists visiting colonial Korea, but also a recurrent motif in textual and visual representations of imperial tourism.[28] It is crucial to note this in order to consider the ways in which Horino’s photographs affirmed and nuanced the colonial stereotypes.

The photography critic Toda Masako offers an incisive reading of the Kisaeng as a perfect (if provocative) model for Horino’s monograph Elegance of Women. To trace her argument, she first identifies josei-bi (literally, “feminine-aesthetics”) as Horino’s artistic interest in the late 1930s, and defines the term as a variant of the more familiar modernist compounds such as kōsei-bi (composition aesthetics), kikai-bi (machine aesthetics), and toshi-bi (city aesthetics). Notably, this aesthetic term is included in the Japanese title for Horino’s monograph Josei-bi no utsushikata / Elegance of Women (literally, how to capture feminine aesthetics). Like his earlier series on monumental industrial structures, which were aimed at discovering a new way of seeing in the machine era, his selection of one hundred female models carried a similar mandate of exploring a new vision. If his exploration of machine aesthetics was clearly inspired by the works of the German New Vision school, his exploration of feminine aesthetics was inspired by Japan’s cultural hybridity (among the models are Caucasian women in Asian-themed dresses, Chinese women in modern Chinese dresses, and Japanese women in Western swimwear).

As Toda reminds us, the monograph was published at the same time that Horino had been disseminating the “Japanese girl in business” series through international press services. The series showcased female professionals in various workplaces: as telephone operators, bus conductors, and film-studio employees. Although Horino’s models are invariably young, athletic, and cheerful — that is, entirely normative by today’s standards — there was a counter-territorial impulse underlining the photographic project of evenly presenting all professions regardless of their social statuses: “the model in the swimsuit, the actress, the dancer, the geisha, and the tea-house girl.”[29] It is not surprising, therefore, that the photographs of Kisaeng in training were included in Elegance of Women or that they showed no sign of licentiousness: just another example of modern female professionals.

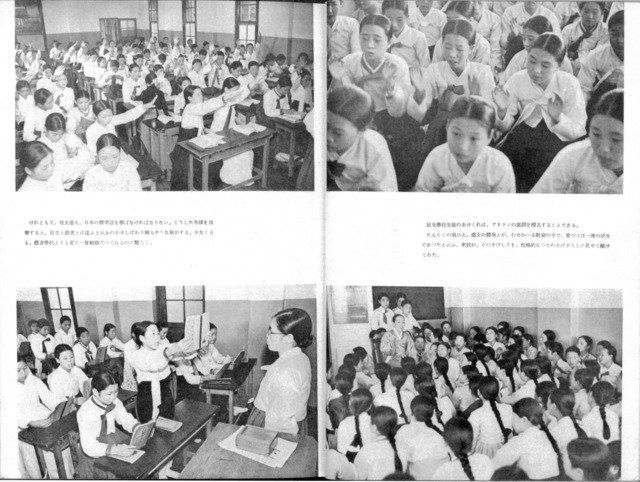

Even though I find Toda’s reading persuasive, her analysis overlooks the fact that Kisaeng had already been a highly iconic motif in tourism visual culture and that Horino was far from unique in emphasizing the profession’s modernity. To shift the focus, we can turn to an alternative presentation of the photograph found in “Kisaeng School” (Kīsen gakkō), a feature that appeared in the December 1938 issue of Camera (figure 5). The feature consists of eleven annotated photographs organized (in a much neater manner than the graph-montage) across eight pages. Sparing the exceptional instance in which a caption, presumably written by Horino, describes “stifling body odor of maidens mixed with the smell of garlic,” which gives away the colonialist and gendered nature of the encounter, the overwhelming emphasis remains on the highly structured curriculum of the school. The text on the corresponding page of the spread thus observes: “It is striking that the school is even more organized than the Geisha schools in Japan.” It is difficult not to notice the clichés of tourism literature being recycled in this feature.

In his analysis of the representation of Kisaeng in audiovisual popular culture, the historian Taylor Atkins describes the multiple roles Kisaeng under Japanese colonial rule played as transmitters of Korean traditional arts, as multilingual performers of Japanese and foreign popular songs, and as licensed sex workers.[30] On the one hand, the institution of Kisaeng was seen as a tradition inherited from the Joseon Dynasty and was fetishized as a remnant of the regime that the Japanese usurped. On the other hand, Kisaeng was a modern institution, fully regulated under the “kenban” licensing system, grafted from Meiji Japan’s highly problematic kōshō system, or the licensed prostitution system.[31]

Fig. 5. Masao Horino, from Kisaeng School/Kīsen gakkō, Camera vol. 19. no. 10, October 1938, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.

Fig. 5. Masao Horino, from Kisaeng School/Kīsen gakkō, Camera vol. 19. no. 10, October 1938, Tokyo, © Eiko Horino, courtesy of the Estate of Horino Masao.Out of a dozen or so licensed Kisaeng businesses, Pyongyang’s incorporated Kijō Kenban stood out for its media visibility, not least for the famous “Kisaeng school” it ran, in which some three hundred adolescent girls were trained in a modern curriculum. The Kisaeng School symbolizes the duplicitous nature of the Japanese perception of Kisaeng in general. Travel essays typically emphasized the bright, young, and talented students in the school with no mention of the profession’s traditional association with prostitution. Take, for example, the radio program titled “Scenes from Kisaeng School,” broadcast from Pyongyang on May 23, 1937, which essentially treated it as a modern professional training school, featuring commentaries provided by the teachers and covering evening classes for dance, popular songs, Japanese, and calligraphy.[32] What is interesting in Horino’s photographs is not so much their difference from the colonial clichés, but rather the ways in which they fit his broader vision for modernist photography. Consistent with Atkins’ broader claim that the Japanese colonial discourse of Korea involved a projection of its own unstable position in modernity, we can find a parallel between Horino’s description of the modern, systematized curriculum of Pyongyang’s Kisaeng School and his career-long campaign to rationalize the work of photographers.

If the spectacles of young, active, and cheerful women photographed by Horino cannot help but appear liberating, it is worth keeping in mind that his celebration of new women, liberated from the patriarchal order, was predicated on their reintegration into the imperial workforce. Needless to say, Horino’s campaign for rationalization happened against the backdrop of the broader program of total mobilization (sōdōin-taisei) that was legally implemented in April 1938, just months following Horino’s journey to Korea. As the labor historian Yutaka Nishinarita reminds us, total mobilization, which the Konoe Fumimaro government drafted soon after committing Japan to a total war in China in the summer of 1937, was an expansive program to procure a labor force that rolled out in multiple phases: recruitment of Korean laborers for key industries in 1937, mobilization of students for patriotic duties in 1938, which was initially limited to school recesses, and the integration of women through associations in 1938.[33]

The modern women Horino celebrated fed into the campaign of mass mobilization; his journey in the colonies was part of the mobilization of the intelligentsia.

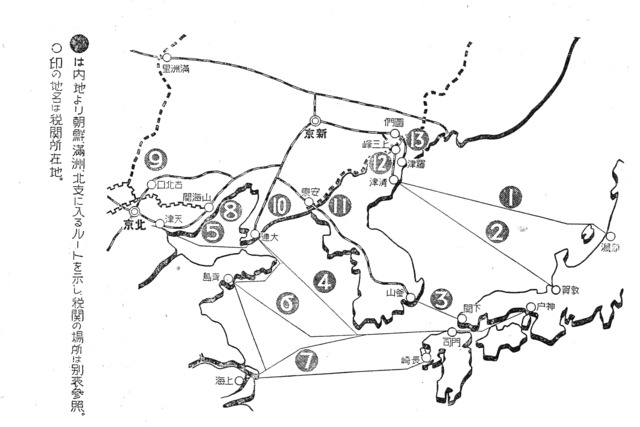

Fig. 6. An illustrated map from Masao Horino, Tairiku e satsuei-ryokōsuru hitotachini, Camera Art 12. 3: 791, September 1940, Tokyo.

Fig. 6. An illustrated map from Masao Horino, Tairiku e satsuei-ryokōsuru hitotachini, Camera Art 12. 3: 791, September 1940, Tokyo.As a final observation, it is important to note the slippages that existed between the two objectives that I have subsumed under the term counter-territorial photography: that is, the objective to transform a land into a territory and the objective to rationalize photography by delegitimizing the expertise of amateur masters. This slippage can be seen clearly in a customized map Horino made for an article entitled “For Those Embarking on a Continental Photography Trip,” which offered a highly detail account of his ten-month journey in Manchuria, North China, and Mongolia and reads as a travel essay and a “how-to” guide in one (figure 6).[34] The map shows the customs and checkpoints that travelers exiting Japan proper inevitably pass through. Even though one of the tourism booklets that published Horino’s photographs opens with an emphatic claim that traveling to Korea should no longer be seen as a “long distant travel abroad [ . . . ] for residents of Kyushu, Korea is closer to travel to than Tokyo or Osaka,” such an illusion of proximity, convenience, and interconnectedness is dispelled by Horino’s map. On the one hand, this map appears to contain a kernel of resistance against the imaginary of an interconnected empire. He repeatedly reminds readers not to confuse continental trips (from naichi, or “inner territory,” to the colonial gaichi, or “external territories”) with domestic trips, offering insider tips on filling out export forms for their cameras, on convincing custom officers of the necessity of multiple cameras (it is best to avoid carrying two identical cameras even with different lenses), and on procuring films where the product lineup is different from how it is in Japan proper. On the other hand, the borderful map of the empire in effect consolidated the new professional demarcations of photographers under the slogan of mass mobilization. For example, he follows up on the seemingly oppositional advice that more photographers venture out of Japan if only to experience the technological superiority of German and American films over Japanese domestic brands with a sharp criticism of “amateur leaders who blindly praise domestic products.”[35] The article thus privileged the objective of courting the mass amateurs’ trust and deposing the amateur leaders at the cost of visualizing a stable, interconnected, and coherent imperial territory.

Conclusion

It is apt to end this essay with a reminder of the gap that had always existed between the modernist visions of Horino and his contemporaries and the reality of wartime Japan. Consider the fact that Horino spent the latter half of WWII in Shanghai, employed by the Army News Service Commission, for which his tasks were primarily bureaucratic with little opportunity for producing work as a photographer.[36] Was this the logical endpoint of modern rationalization that mobilized amateur and professional photographers alike in the service of mass society? Granted, Horino’s predicament in Shanghai might have been more the result of the wartime shortage of photographic supplies than of the photographer’s philosophy. As I have discussed in this essay, however, historically contingent factors such as Japan’s imperial expansionism and the total mobilization of imperial subjects were far from external to Horino’s works, but were instead constitutive factors informing his practices in the early 1930s.

Building on the growing body of scholarship on Horino, this essay has highlighted the active roles imperial geography played in the key turnings points of his oeuvre. Because of the consistency with which Horino pursued his vision for reforming photography as a rational, modern, and socially relevant medium for mass communication, his works provided an opportune case study to question the dominant view of modern art in which exigencies of total war forced artists to suspend their modernist expressions. Drawing on existing scholarship on graph-montage, which has emphasized the experimental dimension of the work that brought together two of Horino’s objectives —to open up “new visions” with photography and to reinvent photography as means of mass communication — I have argued that such experiments did not take place in a political vacuum; they took place in contingent historical contexts I subsume under imperial geography. Borrowing the notion of “territorial photography” from Joel Snyder, I further discussed how the work of visualizing imperial geography was interrelated with new territorial claims made for photography. I elaborated on this interrelation by turning to Horino’s photographs shot in the colonial spaces. For Horino and his contemporaries, there was little contradiction between exploring photography’s potential as a modern medium and enlisting their expertise for building, visualizing, and legitimizing the Japanese empire.

Shota Tsai Ogawa teaches film studies at Nagoya University in Japan and writes on the impact of mass migration on photography and film, and vice versa, with a particular focus on the Korean immigrants in imperial to post-imperial Japan. His writings have appeared in Screen, Japan Focus, InVisible Culture and Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema.

Research for this paper was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17H06734 and University of Chicago CEAS Japan, China and Korean Studies Library, Travel Grants.

Bibliography

- Arima, Manabu. “1930–1940 nendai no nihon ni okeru bunkahyosho no naka no ‘chōsenjin.’” Nikkan rekishi kyodo kenkyuhokokusho: dai 3 bunkakaihen. Edited by Nikkanrekishikyōdōkenkyuīnkai. Tokyo: Nikkanbunkakōryushukai, 2010, 195–218.

- Ariyama, Teruo. Kaigaikankōryokō no tanjō. Tokyo: Yoshikawa hirobumikan, 2002.

- Baba, Nobuhiko. “Toshinojidai o kakenuketa zasshi ‘Hanzai kagaku’ no yakuwari.” Hanzai kagaku: dai-4-kai haibon (Tokyo: Fuji shuppan, 2008), 7–35.

- Gosho, Heinosuke. “Leica Model D.” In Foto Times 11:1 (January 1939): 22–26.

- Hikotaro, Ichikawa, Masao Horino, Rodorufu Foru, Masaharu Fukuda, Masao Takakuwa, and Kunio Kitano. “Shashin-gaikō zadankai.” In Camera 19:12 (December 1938): 575–84.

- Horino, Masao. “Shinkō geijutsu shashin no hyougenkeishiki.” Nihonshashinkai nenkan. Tokyo: Shashinkikaisha, 1932, E1–E16.

- ———. “Soviet no shashin.” Hanzai kagaku, zōkan: Roshia osorubeshi. Tokyo: Bukyōsha, 1932: 173–83.

- ———. “Daigokai kojinshashinten ni saishite.” In Shashin geppō 39:3 (1934): 293–304.

- ———. Josei-bi no utsushikata / Elegance of Women. Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1938.

- ———. “Tairiku e satsuei-ryokōsuru hitotachini.” In Camera Art 12:3 (September 1940): 789–93.

- ———. Manmōkaitakudan no kaisō. Tokyo: Horino-Yoko-kai-jimukyoku, 1993.

- ———. “Jo ni kaete.” In Kamera, me x tetsu, kosei / Camera, Eye x Steel, Composition. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2005, 28.

- Iizawa, Kōtarō. Shashin ni kaere: Kōga no jidai. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1988.

- ———. “Shakai ni hirakareta shashin: Horino Masao no senkusei.” In Nihon no shashinka Horino Masao. Edited by Shigeichi Nagano, Kōtaro Iizawa, and Naoyuki Kinoshita. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1991, 3–6.

- Kanamaru, Shigene. “Amachua narabini shokugyōshashinka.” In Camera Art 12:3 (September 1940): 254–55.

- Kaneko, Ryuichi. “Gurafu-Montaju no seiritsu.” In Modanizumu/Nashonarizumu. Edited by Toshiharu Omuka and Tsutomu Mizusawa. Tokyo: Serika shobo, 2003, 156–77.

- ———. “Biography of Horino Masao.” Vision of the Modernist: The Universe of Photography of Horino Masao. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2015, 3–10.

- Kawamura, Minato. Kīsen: Mono iu hana. Tokyo: Sakuhinsha, 2001.

- Koda, Yuri. Shashin ‘Geijutsu’ tono kyōmen ni: shashinshi 1910 nendai-70 nendai / Photography, Interfacing “Art”: History of Photography from the 1910s to the 1970s. Tokyo: Seikyusha, 2006.

- Lee, Insuk. “Convention and Innovation: The Lives and Cultural Legacy of the Kisaeng in Colonial Korea.” In Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 23:1 (June 2010): 71–97.

- McDonald, Kate. Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017.

- Nishinarita, Yutaka. Rōdōryoku-dōin to kyōseirenkō. Tokyo: Yamakawashuppan, 2009.Shukan Asahi ed. Nedanshinenpyō: Meiji, Taishō, Shōwa. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1986.

- Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea. Impressions of Korea / Chōsen no inshō. Osaka: Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea, 1938.

- ———. Hantō no kinei / Recent Photographs of Korean Peninsula. Osaka: Railway Bureau of the Government-General of Korea, 1938.

- Ross, Kerry. Photography for Everyone: The Cultural Lives of Cameras and Consumers in Early-Twentieth-Century Japan. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015.

- Snyder, Joel. “Territorial Photography.” In Landscape and Power. Edited by W. J. T. Mitchell. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2002, 175–201.

- Takeba, Joe. “Ishokusareta kaigashugi / Transplanted Pictorialism.” In Ikyō no modanizumu: manshushashinzenshi / The Development of Japanese Modern Photography in Manchukuo, Joe Takeba ed. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2017.

- Toda, Masako. “‘Josei-bi’ kara tairisuku e no michinori / The Path from ‘Feminine-aesthetics’ to the Continent.” In Vision of the Modernist: The Universe of Photography of Horino Masao. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2015, 22–31.

- Weisenfeld, Gennifer. “Touring Japan-as-Museum: Nippon and Other Japanese Imperialist Travelogues.” In Positions: Asia Critique 8:3 (Winter 2000): 747–97.

- Young, Louise. Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998, 55–114.

Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 13.

The difference between formal colonies such as Korea and Taiwan on the one hand and the puppet regime of Manchuria is well known. But even for Korea, the word colony was sparingly used, and the dichotomy of Japan proper (naichi) and the outside territory (gaichi) was not consistently maintained. For a study of the unstable imperial geography and the roles tourism played in stabilizing the otherwise unstable statuses of imperial Japan’s territories, see Kate McDonald, Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017), 1–2.

For a study of Nippon as “both an attempt by state-sanctioned representatives of the Japanese empire at self-representation and an invocation to the Western viewer to colonize the country through a kind of tourist gaze,” see Gennifer Weisenfeld, “Touring Japan-as-Museum: Nippon and Other Japanese Imperialist Travelogues,” in Positions 8: 3 (Winter 2000), 750. For a study of Tourism Japan / Kanko Nippon, see Yamamoto Sae, Senjika no banpaku to “Nihon” no hyosho / Expos in Wartime and the Representation of “Japan” (Tokyo: Moriwasha, 2012).

Unlike his contemporaries, such as Kimura Ihei, Natori Yonosuke, and Kanamaru Shigene, who continued their influential careers as photographers and theorists after Japan’s defeat in WWII, Horino focused on managing Minicam, a portable strobe-light flash manufacturer he founded in 1949. Horino Masao, “Chosha ryakureki,” Manmō-kaitakudan no kaisō (Tokyo: Horino Yoko kinen shin'yōkai jimukyoku, 1993), 125.

Art Photography and New Photography are not symmetrical terms in that the former was retroactively defined by the latter as shorthand for the clichéd works of bourgeois amateur photographers who typically used gum bichromate or bromoil processes to give their prints painterly textures. Although amateur masters such as Nojima Yasuzō, Fuchigami Hakuyō, and Fukuhara Shinzō are conventionally categorized as leaders of Art Photography, recent reassessments of their works have underscored their constant negotiation between the tenets of l’art pour l’art and the kind of utilitarian view of photography celebrated in New Photography. See, for example, Yuri Koda, Shashin, “Geijutsu” tono kyōmen ni: shashinshi 1910 nendai-70 nendai / Photography, Interfacing “Art”: History of Photography from the 1910s to the 1970s (Tokyo: Seikyusha, 2006), and Takeba Joe, ed., Ikyō no modanizumu: manshushashinzenshi / The Development of Japanese Modern Photography in Manchukuo (Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai, 2017).

Ryuichi Kaneko, “Biography of Horino Masao,” in Vision of the Modernist: The Universe of Photography of Horino Masao (Tokyo: Kokusho-kankōkai, 2015), 4.

Kōtarō Iizawa, “Shakai ni hirakareta shashin: Horino Masao no senkusei,” in Nihon no shashinka Horino Masao, edited by Shigeichi Nagano, Kōtaro Iizawa, and Naoyuki Kinoshita (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1991), 3.

Horino’s entry on New Photography for an almanac gives us an indication of the wide range of German-language publications he had read and commented on, such as Moholy-Nagy’s influential Painting, Photography, Film (1925), Franz Roh’s Foto-Auge (1929), and Renger-Patsche’s Die Welt Ist Schon (1929). See Masao Horino, “Shinkō geijutsu shashin no hyougenkeishiki,” Nihonshashinkai nenkan (Tokyo: Shashinkikaisha, 1932), E1–E16.

By the 1920s, artists and photographers in Japan had a more or less contemporaneous access to trends in Europe not only via publications, but also through individuals returning from prolonged overseas stays. A case in point is the avant-garde playwright Murayama Tomoyoshi, who was able to use his connections with the artistic milieu in Germany in order to realize the exhibition. Horino was involved in the organization through the International Photography Association. See Kōtarō Iizawa, Shashin ni kaere: Kōga no jidai (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1988), 56.

For his comments on Moholy-Nagy, see Masao Horino, “Jo ni kaete,” in Camera, Eye x Steel, Composition (Tokyo: Kokusho kankokai, 2005), 28. For his comments on Russian posters, see “Soviet no shashin,” in Hanzai Kagaku, zōkan: Roshia osorubeshi (Tokyo: Bukyōsha, 1932), 173–83.

For a thorough overview of “graph-montage,” See Ryuichi Kaneko, “Gurafu-Montaju no seiritsu,” in Modanizumu/Nashonarizumu, edited by Toshiharu Omuka and Tsutomu Mizusawa (Tokyo: Serika shobo, 2003), 156–77.

For an example of a high-end hobby photographer’s view of Leica Model D, see the film director Gosho Heinosuke, “Leica Model D,” in Foto Times 11:1 (January 1939): 22–26.

An interesting use of this work is found in the History Museum of J-Koreans in Tokyo where visitors encounter a blow-up of a few of Horino’s photographs from Tamagawa-beri alongside a diorama reconstructing the work site on Tama River. The caption and the museum catalog interprets the work as a rare exposition of the harsh labor conditions for colonial Korean laborers and credits it to Kitagawa rather than Horino.

Joel Snyder, “Territorial Photography,” in Landscape and Power, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2002), 175–201.

Masao Horino, “Daigokai kojinshashinten ni saishite.” In Shashin geppō 39:3 (1934): 299.

For a detailed account of the mass media’s active role in fueling the war fever of the 1930s, see Young 1998, 55–114. For yen-bon’s impact on the reading population in the 1920s and the magazine readership in the 1930s, see Baba Nobuhiko, “Toshinojidai o kakenuketa zasshi ‘Hanzai Kagaku’ no yakuwari,” Hanzai Kagaku: dai-4-kai haibon (Tokyo: Fuji shuppan, 2008), 7–35.

The starting monthly salary for primary-school teachers in 1931 was 45–50 yen; the same for police officers in 1935 was 45 yen. See Shukan Asahi, ed., Nedanshinenpyō: Meiji, Taishō, Shōwa (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun, 1986), 92.

Masao Horino, “Tairiku e satsuei-ryokōsuru hitotachini,” in Camera Art 12:3 (September 1940): 791–93.

Teruo Ariyama, Kaigaikankōryokō no tanjō (Tokyo: Yoshikawa hirobumikan, 2002), 17–88.

The difference between formal colonies such as Korea and Taiwan and the puppet regime of Manchuria is well known. But even for Korea, the word colony was used sparingly, and the dichotomy of Japan proper (naichi) and the outside territory (gaichi) was not consistently maintained. For a study of the unstable imperial geography and the role tourism played to stabilizing the otherwise unstable statuses of imperial Japan’s territories, see Kate McDonald, Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017), 1–2.

Hikotaro Ichikawa, et al., “Shashin-gaikō zadankai,” in Camera 19:12 (December 1938): 575–84.

Shigemine Kanamaru, “Amachua narabini shokugyōshashinka,” in Camera Art 12:3 (September 1940): 254–55.

See, for example, Taylor Atkins, Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910–1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 176.

For the discussions on illustrated albums such as Chōsenjin bijinhōkan (Encyclopedia of Korean Beauties), published in 1918 by the head of colonial Seoul’s daily Keijo shinbun, and Kijōkīsenshashinchō (Photography Book of Kijō Kisaeng), published by Pyongyang Kisaeng organization (date unknown), see Kawamura 2001, 125–30, 142–47.

Masako Toda, “‘Josei-bi’ kara tairiku e no michinori / The Path from ‘Feminine-aesthetics’ to the Continent,” in Vision of the Modernist: The Universe of Photography of Horino Masao (Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2015), 26.

“Kīsen gakkō fukei,” in Asahi Shimbun, May 23, 1937, morning edition, 20.

Yutaka Nishinarita, Rōdōryoku-dōin to kyōseirenkō (Tokyo: Yamakawashuppan, 2009).

Masao Horino, “Tairiku e satsuei-ryokōsuru hitotachini,” in Camera Art 12: 3 (September 1940): 791–93.