Archiving the Spirit: Suda Issei’s Fushi Kaden and “Essential” Japan

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract:

This article analyzes images taken from a photo series, entitled Fushi Kaden, produced by the Japanese photographer Suda Issei (b.1940). This series does not necessarily conform to a conventional understanding of the archive in that the images are both contemporary and purposely creative. However, my central interest is not to establish whether archives are in fact curated, but to understand Fushi Kaden in relation to writing on the archive by Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. In Archive Fever, Derrida argues that the archival impulse is inherently driven by a need to affirm identity. As I will argue, Fushi Kaden represents a turn to the past by Suda in order to preserve, or uncover, an “essential” Japanese identity. This impulse reflects Suda’s condition as a modern subject who perpetually seeks self-recognition through turning to a mythical past. In The Archeology of Knowledge, Foucault contends that the archive is “the system of discursivity” in a given society that ultimately determines accepted truth-value. In this sense, I will investigate how Suda’s photographic work functions within discourses about Japanese identity, an important undertaking given that photography retains a strong, although highly contestable, cultural association with absolute “reality.”

Suda’s Archive Fever: Identity and Discourse

In Archive Fever, Jacques Derrida argues that although we commonly associate the archive with the past and usually regard such collections as a literal record, archives are also inherently concerned with the future. For Derrida, the archive “call[s] into question the coming of the future.”[1] The archive is ostensibly a particular definition of the past—however objective the archivist’s methods— and as a definition takes its meaning from an opposing concept of future. The archive is a “question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow.”[2] This point is especially important to the following discussion of Japanese photographer Suda Issei’s (b. 1940) seminal photo series, Fushi Kaden.[3]

Suda began this series in the early 1970s and published the collection as a monograph in 1978. It is an assembly of portraits and various images of domestic, rural, and traditional spaces taken during Suda’s travels throughout Japan. In the discussion that follows, I will suggest that this series represents a particular definition of the past that was also a clear expression of concern about Japan’s modern present.

Of particular relevance to my discussion is what Derrida refers to as “archive fever” or “the archive drive.”[4] Derrida conceives this drive in the context of Freud’s “death drive,” the often irrepressible urge toward self-annihilation that is an essential feature of the human psyche. Although it might be misconstrued as a literal wish for death, this fever is better understood as an urge to return to origins, to the nothingness from which each person emerges into the world. In terms of the archive, Derrida argues that this drive is at once an act of effacement and one of self-affirmation. The archive, moreover, invariably requires a substrate on which the archivist leaves her impression in the process of bringing it into being; in other words, she conceals or erases some part of that substrate.[5]

It is important to note here that by “substrate” Derrida does not mean an origin or foundation, but quite simply that which the archivist inscribes on. This is why Derrida argues that “archive fever” in fact “works to destroy the archive: on the condition of effacing but also with a view to effacing its own ‘proper’ traces—which cannot consequently be called ‘proper.’”[6] Furthermore, to inscribe oneself is to affirm identity, an act that is “first of all self-repetition, self-confirmation in a yes, yes” that as an affirmation of self-identity inherently requires a designation of “the One,” or “the Unique.”[7]

In Archive Fever, Derrida makes this point in response to the Jewish scholar Yerushalmi’s essentialist claims about Jewish identity. Derrida’s point, however, is readily applicable to any essentialist designation, including the hypostatized essential Japan that Suda attempts to recover in Fushi Kaden. In Suda’s case, we might conceive of the photographer himself as the archivist, photographing in Tokyo but also frequently traveling to Japan’s provincial areas with an eye to the creation of an archive, in this case a book of photographs, a format Derrida considers “another species of the archive.”[8] Consequently, we might consider the landscape, traditions, memories, and subjective experience belonging to the subjects whom Suda photographed as a substrate, itself an archive of sorts. This is proper to Derrida’s conception of the archive as a kind of layering of impressions that nonetheless always contains a promise, for the archivist, of access to the primordial.[9]

Michel Foucault’s conception of the archive is quite different from its classical definition as a cohesive assembly of artifacts that are seen to represent the past. He argues that contrary to a “sum of all the texts that a culture has kept upon its person as documents attesting to its own past, or as evidence of a continuing identity,” the archive is the “system of discursivity” that governs what can be said.[10] This is comparable to Derrida’s description of the archive as the domain of the “archon” (those who govern absolutely) by which society is ordered.[11] Foucault distinguishes the “historical a priori” from a classical understanding of a priori as grounds for validation. The historical a priori, for Foucault, is “a condition of reality for statements, a set of rules that “characterize a discursive practice.”[12]

Statements function within discursive systems, and as a cohesive whole these multifarious systems constitute the archive, that which ‘differentiates discourses in their multiple existence and specifies them in their own duration.’[13] In this sense, the statement is defined ‘at the outset’ by the archive which is thus ‘the system of its enuncibility.’[14] Foucault’s conception of the archive is of particular importance to the following analysis of Suda’s photographic project, Fushi Kaden, because it disrupts the central premise of capturing an originary locus for an essentialist Japanese identity. In a sense, Suda, by traveling throughout rural Japan to make his photographs, conceives of these areas as archives in a classical sense, as repositories of authentic ‘documents’—or at least the raw materials for the production thereof—to substantiate a particular statement about a mythical Japanese ‘essence.’ However, if the Fushi Kaden project is understood in terms of Foucault’s archive, we might consider this project a statement, an enunciation shaped by a broader ‘system of discursivity’ about Japanese identity.

Suda, Terayama Shuji, and a Postwar Longing for Origins

Suda Issei graduated from the Tokyo School of Photography in 1962. In 1967 he became the stage and publicity photographer for the avant-garde theater group Tenjō Sajiki. This group was headed by Terayama Shuji, an avant-garde poet, filmmaker, stage director, and occasional photographer whose surreal and often shocking theater and film work had made him a provocative and well-known public figure in the 1960s and 1970s. Of all his formative experiences, it seems Suda’s time with Tenjō Sajiki exerted the greatest influence on his subsequent photographic work. There are three themes in Terayama’s work that filtered through into many images that Suda produced. First and foremost was an interest in traditional or ‘native’ Japanese culture, specifically traditional festivals and Nō theater. Second, and related to this, was an abiding preoccupation with an essential Japan believed to be present in the rural landscape and its communities.[15] Third, both Terayama and Suda sought to give expression to the underlying mystery of daily existence through their work.

It should be noted that although Terayama’s work was an important influence on Suda, and that the work of each is characterized by shared themes, the respective styles in which both artists communicated these themes are in distinct contrast. While a confluence of traditional culture and surrealism is redolent in the imagery that each produced, because Suda’s work follows a documentary style it is markedly subtler than that of Terayama. The entirely fictional nature of Terayama’s work gives it an otherworldly feel; a disjointed world in which symbols of tradition and nationalism are mingled with highly sexualized themes and imagery. Carol Sorgenfrei has identified four distinct phases of expression in performances by Tenjō Sajiki, the first two being especially relevant to Suda’s work. In the first, between 1967 and 1969, themes of ‘rural superstition, folklore, dreams, and magic’ are mixed with highly dramatic music, lighting, ‘shocking (often vulgar or highly sexualized) imagery’ and black comedy.[16] The second phase, between late 1968 and 1970, was underpinned by a belief in the innate creativity of the common person and thus non-professionals were hired as actors. The driving motivation behind the works produced in this period was to ‘advocate personal metamorphosis through encouraging ordinary people to express themselves and to develop the capacity for imagination.’[17] Implicit in this was a rejection of the rigid structures of modern society accompanied by a yearning for an imagined premodern Japan. The third and fourth phases are perhaps less pertinent to discussion of Suda’s photographs, but involved an effort to break down the structures of traditional theater by performing in unconventional venues, and later by directly involving the audience in often confronting ways.[18]

A survey of Suda’s photographs reveals strong influences from the first two phases, in particular a preoccupation with traditional or ‘native’ culture as a subject.[19] Suda frequently seeks out people in traditional dress who are engaged in traditional performance or ceremony. The influence of the second phase is perhaps less immediately clear; however, Suda’s repeated depiction—and repetition is a fundamental feature of archive fever as Derrida conceives it—of those performing traditional culture hints at a need to uncover an essential creativity in the average person. Crucially, Suda chose to travel to rural areas and photograph ordinary people in order to fulfill this need; this reflects Terayama’s similar perception of the countryside as a last vestige of a discarded enchanted world in which remnants of premodern Japanese identity are still discernable. As Sorgenfrei has pointed out, such an attitude was not uncommon in artists of this period given the devastating aftermath of the Pacific War, American Occupation, and social upheaval that had marked the previous three decades. Many artists sought a Japanese identity ‘not totally bound to the United States’ and mourned the loss of Japanese purity.[20]

Terayama’s 1974 film Den’en ni shisu (usually translated as Cache-Cache Pastoral) evokes this sense of longing for the premodern. The film is set in an ahistorical, often disturbing, but unmistakably rural landscape infused with dark magic and superstition. A central theme in the film is a presumably autobiographical yearning for the mother figure who is embodied in both a literal sense and in the character of a neighbor’s young wife. The latter is initially a good woman who falls from grace, and in one of the final scenes sexually overpowers the young male protagonist who seems to represent Terayama himself. There are clear autobiographical overtones here, as Terayama’s own mother was a troubled character considered wanton by postwar moral standards due to her relations with American soldiers, and was often an absent figure for the young Terayama. It is therefore little surprise that Terayama’s complex feelings about his mother would become a central theme in his work.[21] Yet the film, and especially the mother figure, can also be taken as an allegory that works through ideas about Japanese identity, principally through the body of the corrupted mother figure, an innocent Japan corrupted by American influence and modernization in general. This is compounded by the ambivalent sense of attraction and repulsion the central character feels towards the mother figure as originary source, as Japan’s traditional past, and in the Freudian sense of the death drive, the yearning for self-annihilation that constitutes a search for origins.

Although the mother figure herself is largely absent from Suda’s landscape, this relation to origins that characterizes Terayama’s artistic production is also a central theme in Suda’s work. His images are peopled by seemingly ordinary, down to earth rural folk, but also dark and sinister figures that evoke a similar sense of dark enchantment as Terayama’s work. This is quite evident in Fushi Kaden. Fushi Kaden as a photo series was begun in the early 1970s and published in serial form in Camera Mainichi between 1975 and 1977, then as a complete volume in 1978. Suda created the images during his travels around Japan and especially in his ventures to the more remote areas of the archipelago. The title of the series references a classic fifteenth-century book of the same name, which translates as ‘Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style’, written by seminal Nō theater director and actor Zeami Motokiyo (c. 1363–c. 1443). The book is essentially a treatise on the craft of Nō theater, and was an important influence on Suda, who had read it ‘avidly’.[22] Suda’s appropriation of this title is a telling signifier of his intention to express a return to origins in the series. As Ryūichi Kaneko and Ivan Vartanian contend, ‘with this title, Suda declared his return to an emotional landscape that pre-dates the rise of cities.’[23]

Zeami’s Fushi Kaden and Nō: Archetypes of Japanese “Essence”

Nō theater might be considered emblematic of the principles promoted by Japanese authorities in the modern era as central to a national Japanese culture. For example, Nō was a centerpiece in the conception of Japan as a museum that, as Gennifer Weisenfeld has argued, the Japanese government sought to market to the West during the 1930s through its Nippon magazine.[24] According to Donald Keene, narrative in this form of theater is less important than its sensory aspects, and thus unlike in classical Greek plays, characters in Nō plays are not grounded in a common humanity. Instead, characters are ‘hardly more than beautiful shadows, the momentary embodiments of great emotions.’[25] The actors’ slow, meticulously studied movements also emphasize aesthetics – the audience is compelled to pay at least as much attention to these aesthetics as to the narrative unfolding before them. Moreover, Donald Richie contends that the inscrutability of the lyrics sung by the actors—often because they are in an archaic dialect not accessible to many Japanese—directs appreciation toward the style and tone of delivery and not the content (although accompanying texts were often provided to help decipher the lyrics).[26] Last, and perhaps most significant, is the limited expression available to the actor due to the traditional practice of wearing masks: the mask erases the individual identity of the performer. While it is argued that this individuality is expressed through subtleties of movement and voice, this is something perhaps only an aficionado would observe.[27] The mask thus becomes a sign, a signifier of an abstract entity.

Thus Nō theater’s intensely stylized nature promises an experience that transcends temporal existence, a fact that enabled Nō’s incorporation into the national imaginary as a signifier of an essential Japanese culture. This became particularly important after the Meiji Restoration when Nō, although initially rejected by the new regime due to its strong connection to the Tokugawa Shogunate, soon became an important exemplar of nationalistic Japanese culture for display to visiting foreign dignitaries in much the same way that opera had been shown to Japanese diplomats visiting Europe. Later, wartime governments were keen to promote Nō as a form of Japanese culture unsullied by foreign influence, to the extent that new plays were written that emphasized patriotic values.[28]Although performed widely between 1942 and 1945, these works disappeared after the war ended. In the postwar era, SCAP (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers) initially opposed the performance of Nō due to this connection to wartime propaganda. However, the genre underwent resurgence and by the mid-1960s—just before Suda commenced the Fushi Kaden photo series—performances were at ‘a high level.’[29]

Zeami’s Fushi Kaden, also known as Kadensho, was one of several texts the famous actor wrote about the craft, and the collection of these works is said to have shaped Nō into its present characteristic form. Zeami is accordingly an icon of the genre, a founding father to the extent that an unbroken hereditary line can be traced from him to the present-day Kanze School, a troupe still dedicated to Zeami’s teachings.[30]The title Fushi Kaden is commonly translated as "Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style." This treatise seeks to enable the aspiring actor to reach the apex of his abilities (Nō actors are traditionally male). This apex constitutes the full realization of the actor’s hana (flower), the cohesive manifestation of all the genre’s skills into a transcendent performance. In his foreword to the 1968 edition of Kadensho, Shūseki Hayashi contends that ‘to have hana is to have grasped the universal within the individual.’[31]

Suda’s interest in Nō theater, and what he absorbed through avid reading of Zeami’s writings on Nō, were transferred to his own Fushi Kaden project. Suda was especially interested in “native” culture, of which Nō is arguably an archetypal example, given its long history and highly preserved status. Nō is preserved in the sense that techniques and methods have been increasingly codified since the late 16th century.[32] This codification was intended to distil the essence of the genre and in turn suspends it in time, making this art form susceptible to interpretation as ahistorical, and thus contributing to a mythical and essential Japanese culture. Consequently, Nō became a reference for the modern Japanese subject in the postwar era who sought an identity independent of the United States. Yet the connection between Suda’s photographs and Nō is not entirely explicit. If this were the case Suda might have photographed Nō performances in order to further preserve what he saw. Instead, for Suda, Nō represented an impetus for discovery, to seek out some “unique” Japanese experience that seemed to be inherent in the various rituals and ceremonies he photographed in the countryside. A clear link to performance is evident in the following photographs (figs. 1 and 2):

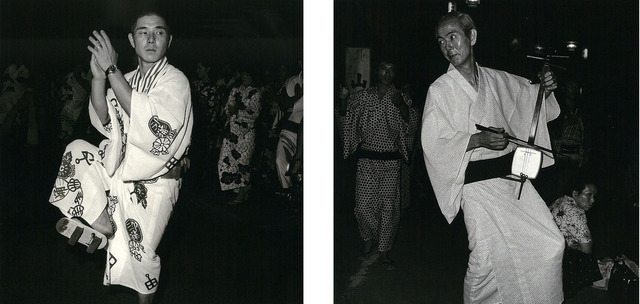

Fig. 1. (left) Gujohachiman Gifu, 1976. Plate 87 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 2. (right) Kaze no Bon Yatsuo Toyama, 1976. Plate 98 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 1. (left) Gujohachiman Gifu, 1976. Plate 87 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 2. (right) Kaze no Bon Yatsuo Toyama, 1976. Plate 98 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Removed from the highly stylized and static nature of Nō, these images nevertheless have an indirect connection to Nō in their clear depiction of traditional performance as craft in action. The intimate, snapshot feel evokes a sense of the vernacular. In the act of performance these men might be accessing the primordial Japanese experience that Nō signifies. This is suggested by the way each has been captured in an almost casual pose; traditional performance seems to come naturally to these men. In the background, this effect is enhanced by faint impressions of fellow performers also in casual poses. Both figures seem to have an easy access to an ordinary Japanese experience, and furthermore their casual demeanor makes this experience seem readily accessible to those seeking to identify as Japanese. This effect functions on a symbolic level as well: each man is captured so as to evoke a sense of the statuesque, frozen as emblems in the broader iconography of a mythical and “authentic” Japanese culture.

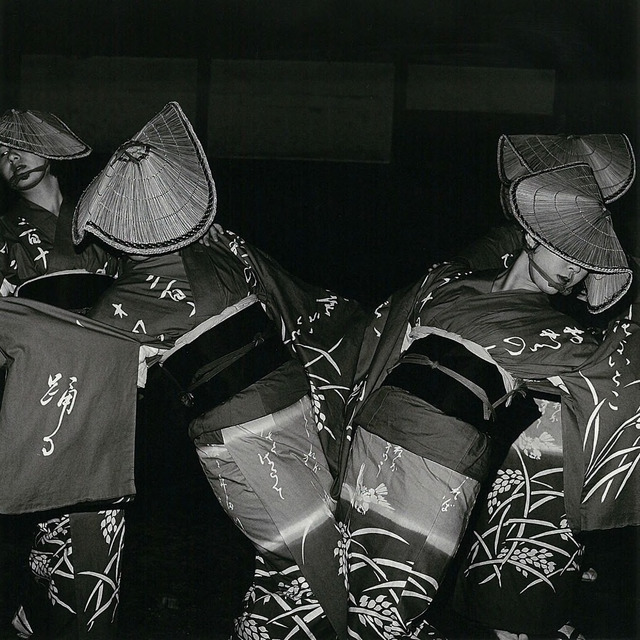

Fig. 3. Kaze no Bon Yatsuo Toyama, 1976. Plate 99 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 3. Kaze no Bon Yatsuo Toyama, 1976. Plate 99 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. A similar effect is at play in figure 3, as again the performers are captured in motion; however, the mildly distorted manner of the dancers’ poses creates an unsettling effect. Despite this, a dynamic grace is still discernable in each performer that speaks of an easy association to a “native” Japanese experience. The performers’ bodies at once merge and yet resist each other in a symmetrical pattern that transforms them into almost entirely stylized functionaries. This, in conjunction with the concealment of most of the dancers’ faces, results in an impression of anonymity. Suppressed individualism suggests an essential and particular Japanese aesthetic. Although the subjects’ costumes and the traditional performances in which they participate signify a certain historical Japan, for Suda traditional costume and performance also signify an idealized originary Japan grounded in aesthetic experience that is conceived of as being opposed to modernity.

While the above images are clearly products of specific sociopolitical and cultural circumstances in postwar Japan, Suda has nonetheless suggested a sense of native experience in two ways: first, by evoking a sense of natural association to aesthetic practice in his subjects; and second, by fashioning these same subjects into static signs that reflect a putatively timeless and uniquely Japanese aesthetic. Both effects rely on the photographer’s ability to suspend his subjects in motion, which is achieved through his use of camera flash. This is a notable choice; an alternative might have been to use a film suitable for low-lighting situations. This would have meant a more grainy appearance, higher contrast, and most likely some motion blur, all of which would have resulted in a very different impression in the images. Instead, Suda’s use of the flash, which allows him to use a fine-grained film, suggests a quest for clarity. He seeks a heightened reality in these images; having sought out subjects that in themselves point to an originary Japanese mode of being, Suda looks to go beyond this. He seeks an imagined originary moment of Japanese being, a transcendent reality that lies just beyond the reach of everyday experience, the very origin that archive production promises the archivist.

Penetrating the Surface of Modern Life

In her analysis of Naitō Masatoshi's photographs taken both in the rural isolation of Tōno and urban sprawl of Tokyo, Marilyn Ivy illustrates how Naitō’s use of flash—in conjunction with high contrast—posits an allegory of the blinding trauma of modern experience placed in stark relief to ‘evoke a dark landscape on the margins of the enlightened discourses and scenes of Japanese modernity triumphant.’[33] In Ivy’s analysis, the flash in Naito’s photographs imposes an erasure of the modern; detail is ‘bleached’ from the everyday in order to accentuate the blackness that surrounds it.[34] This ‘dark landscape’ reflects unacknowledged trauma from Japan’s past: the dark underside of modern experience in Naitō’s Tokyo images, and the dark mythology associated with Tōno through the ethnography famously conducted by Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962) in the area.[35] In contrast to Suda, Naitō employs the flash as an allegorical device to draw attention to the dark sub-terrain of modern Japan. Suda, on the other hand, employs the flash in a more literal fashion, although he inadvertently produces a similar effect to that which Ivy describes. In opposition to the high contrast, grainy expressiveness of Naitō’s images, Suda seeks absolute clarity through the use of a medium-format camera that produces negatives of relatively higher resolution, and fine-grained film processed to render a wide gamut of tonality in conjunction with his use of the flash. All of these methodological devices combine to bring the everyday of rural life into sharp relief.

Suda’s use of flash is at its most distinctive when he is photographing traditional ceremonies, such as in the above images. There are clearly some practical considerations behind this, given that many of these photographs have been taken at night and thus available light was presumably poor. Nonetheless, it might have been possible for Suda to utilize a tripod and capture these dancers at a slower shutter speed, blurring their movements and producing more fluid images – an entirely different effect. Furthermore, Suda might have elected to utilize the flash differently, for instance by using it off-camera and thus avoiding the intense, frontal illumination that often results. The two images below (figures 4 and 5) are perhaps the most striking examples of this uncompromising use of frontal flash, which produces an effect that suggests the photographer’s desire to uncover some mythical, primordial essence in the respective subjects.

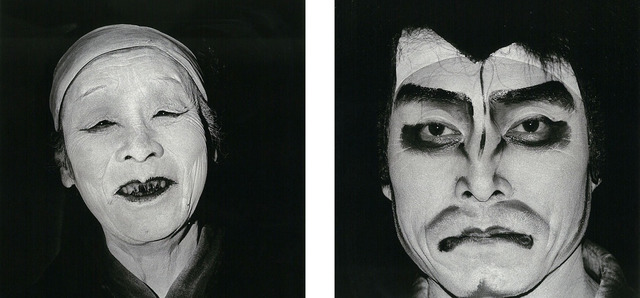

Fig. 4. (left) Yo-matsuri Chichibu Saitama, 1975. Plate 89 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 5. (right) Teppo-matsuri Ogana Chichibu Saitama, 1976. Plate 132 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 4. (left) Yo-matsuri Chichibu Saitama, 1975. Plate 89 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 5. (right) Teppo-matsuri Ogana Chichibu Saitama, 1976. Plate 132 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. The bright, penetrating light of the flash in these images exposes all of the minute surface details on the subject’s skin, so that each wrinkle and blemish is defined. The flash in these photographs also produces a similar effect to that described by Ivy in Naitō’s images, as the men’s faces are isolated against inky black backgrounds. The effect is that these faces seem to emerge unsettlingly from a darker realm of traditional Japanese mythology. Yet at the same time the sharp detail evokes the forensic view of the microscope and reflects the photographer’s penetrating gaze. Thus, somewhat paradoxically, these images simultaneously suggest tradition and modernity, or more precisely, an ahistorical past through Suda’s modern lens.

Almost the opposite seems to be happening in the photograph below (figure 6), as three girls in traditional costume are illuminated against the urban landscape:

Fig. 6. Miuramisaki Kanagawa, 1977. Plate 7 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 6. Miuramisaki Kanagawa, 1977. Plate 7 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. This image evokes an effect different from to those above in that here, Suda’s subjects are captured from farther away and appear unconscious of the photographer’s presence. This lends the image a less forensic quality, at least in a straightforward sense, as the flash has not exposed the same level of detail on the subjects’ bodies. However, there is a sense of the archive in this image, the flash seems to single out the girls as originary traces of Japan’s past by lifting them from the surface, or indeed substrate, of a modern landscape. There is a sense that the girls are captured, or collected, so as to be displayed to the viewer. Furthermore, the choice of the young girls as subjects connotes purity, and thus suggests an unsullied premodern Japanese spirit. This sense is heightened by the attire worn by the subjects, which functions as a literal sign of tradition. In combination with the seemingly casual nature of the scene, this picture suggests the archive in the sense that these girls, conceived as signifiers of the past in contrast to their modern surrounds, have been appropriated for incorporation into Suda’s collection, itself a cohesive assembly of signs, ‘a consignation’ in Derrida’s terms, which defines Japan in relation to an origin.[36]

A Taxonomy of Spirit

The impression of Suda as collector is also reflected in his use of framing and the poses in which he often captures his subjects. His choice of square format in conjunction with a tendency to centralize his subject in the frame gives his images a sense of taxonomy, especially when Fushi Kaden is viewed as a cohesive whole. The notion of photographic taxonomy is notably associated with August Sander’s series Citizens of the Twentieth Century, a large, posthumously assembled series of portraits taken in Germany in the early twentieth century. In this context, the viewer gains a sense that Suda is assembling a collection of “types” much like Sander’s. In contrast to Suda’s work, however, Sander’s was a self-acknowledged effort towards a literally objective study, a study in New Objectivity, and hence all subjects are complicit in the project, carefully posed, and fixed to the center of the frame – figuratively pinned in place. Suda is not quite so literal; he does not see ultimate reality in the temporal, objective “truth” in front of the lens but as something that is located just below the surface fabric of everyday existence and which, therefore, must be drawn out. To access this, he often seeks to almost trick the subject, to disrupt their conscious posing in order that they might reveal a deeper essential truth to the camera. Moreover, Suda’s “types” are intended to provide a composite picture of an imagined authentic Japan, or Japanese life, that has been wrenched away by the incursion of modernity and the experience of annihilation in war, rather than a straightforward taxonomy. Despite this important difference, a similarity to Sander’s work is apparent in the way the subject sometimes appears almost pinned in place, fixed to the center of the frame, such as in figures 7 and 8):

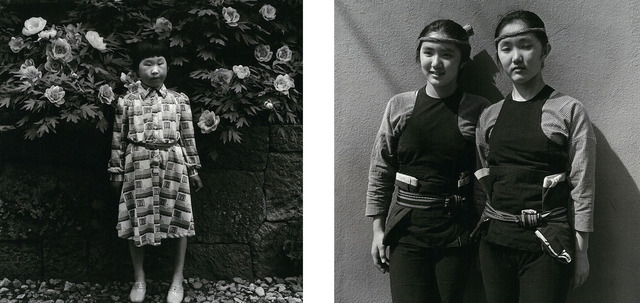

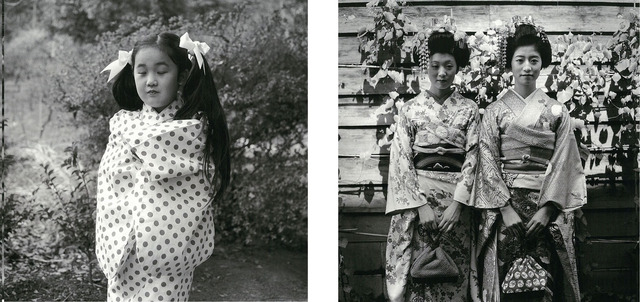

Fig. 7. (left) Botan-matsuri Myounji-Temple Shiobara Tochigi, 1976. Plate 40 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 8. (right) Sanja-matsuri Asakusa Tokyo, 1976. Plate 29 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 7. (left) Botan-matsuri Myounji-Temple Shiobara Tochigi, 1976. Plate 40 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 8. (right) Sanja-matsuri Asakusa Tokyo, 1976. Plate 29 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. This effect is particularly noticeable in figure 7, in which the young girl seems to be held in an awkward position, suggesting her discomfort at being captured in this way. Although this effect is less pronounced in figure 8, the girl in it is similarly awkwardly posed, and also emits a sense of wanting to struggle free. I should note that I do not intend here to suggest that the photographer has in anyway actually trapped these subjects, or has permanently fixed or erased their identities. Rather, I want to bring attention again to the particular way in which Suda is assembling an archive in Fushi Kaden.

In keeping with the idea of taxonomy, Suda employs other motifs to denote different types that are not necessarily classifications of character but of experience. Aside from frequently being depicted in traditional costume, the subjects are also often photographed in the context of nature, or a “natural” context, such as in figures 9 and 10:

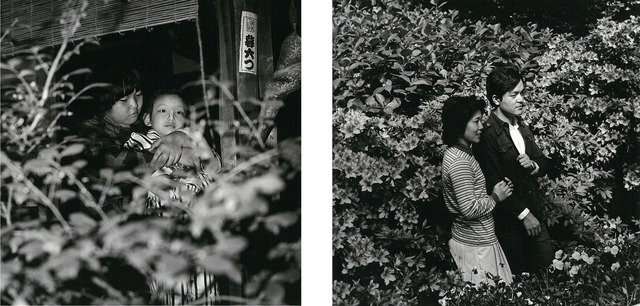

Fig. 9. (left) Sanja-matsuri Asakusa Tokyo, 1976. Plate 32 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 10. (right) Kamakura Kanagawa, 1975. Plate 38 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 9. (left) Sanja-matsuri Asakusa Tokyo, 1976. Plate 32 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 10. (right) Kamakura Kanagawa, 1975. Plate 38 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. There is a sense of voyeurism in these two images. In the left-hand photograph this is suggested by the camera’s position behind the branches in the foreground, as if the photographer is observing his subject while concealed behind the bushes. Although it is not possible to know whether this was the case, given that this image is clearly lit by flash the subjects must undoubtedly have known after the fact that they had been photographed. This sense of the photographer’s self-concealment evokes a feeling that we are viewing a rare and special phenomenon, a unique moment between the two subjects caught in their natural environment. The right-hand photograph conveys a similar sentiment in that Suda has captured a private moment between two people, although without such an apparent sense of voyeurism. And furthermore, an impression of a fleeting connectedness to nature is given in that the couple seem to have arisen from the surrounding foliage and will soon recede back into it. Although the subjects in these images are not especially premodern in appearance, both photographs nonetheless seem to record a particular intimacy of Japanese life discursively associated with a traditional and unique Japanese experience, a subjective identity distinguished by an intimate connection with nature. This is particularly so when viewed in context of the entire Fushi Kaden series; they contribute to the “consignation” of premodern Japan that Suda has assembled in the book.

The images discussed thus far might be taken as somewhat literal iterations of Suda’s quest to record the last vestiges of an originary Japanese experience. This has been largely accomplished by photographing his subjects in traditional outfits, engaged in traditional performance, and in the context of the natural environment. However, Suda also employs another especially modern perspective to expose a subterranean Japan. As discussed earlier, avant-garde theater director Terayama Shuji was an important influence on Suda, and surrealism was clearly a central influence on Terayama’s work. In Suda’s photographs, surrealist themes are reflected in the way he tries to catch his subjects off-guard, in the temporal/spatial interstices between gestures and poses. This strategy seems geared towards his desire to delve below the subjects’ everyday, conscious, façade in order to expose their subconscious experience, so that they might reveal something about an authentic Japanese essence to the photographer. This can be observed in figures 11 and 12:

Fig. 11. (left) Ume-matsuri Sankeien Yokohama Kanagawa, 1977. Plate 13 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 12. (right) Hanagasa-matsuri Obanazawa Yamagata, 1976. Plate 81 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012.

Fig. 11. (left) Ume-matsuri Sankeien Yokohama Kanagawa, 1977. Plate 13 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. Fig. 12. (right) Hanagasa-matsuri Obanazawa Yamagata, 1976. Plate 81 from Fushi Kaden, by Suda Issei. Akio Nagasawa Publishing, Tokyo, 2012. The subjects in both photographs have been caught while blinking, in the moment between one countenance and the next. This might be understood as Suda trying to draw out the individuality of the subject, the blink adding a certain human dimension to what might be otherwise somewhat staid portraits, and this may well have been his conscious intention. However, when taken in the broader context of the Fushi Kaden series, it is difficult not to also understand this particular move, or device, as an attempt to symbolize a break in the flow of the everyday, literal experience and thus suggest something deeper and subconscious. By catching his subjects off-guard in this manner Suda hopes to parenthesize the conscious individual expressions of his subject and instead suggest a more universal experience.

A Discourse with History

As illustrated earlier, a common motif in Fushi Kaden is the association of the Japanese subject to the natural world. This holds clear connotations to an historical conception of Japanese identity as grounded in the aesthetic experience of nature. As Julia Adeney Thomas has argued, this particular idea of nature became a central tenet of Japanese state political ideology in the 1930s.[37] The association of Japan with nature and aesthetics was a consequence of a rapid modernization that led to a fear for the loss of traditional life. This has been a feature of many modern societies. Because in Japan the modern was largely seen as an imported set of ideas, however, modernity also became associated with the West. This resulted in the construction of a sublime and aesthetic Japanese identity that was counterposed to a perceived cold and rational West. The most significant example of this was the Romantic movement of the 1930s—which became strongly associated with wartime ideology—that conceived Japanese essence as ahistorical and associated with nature and aesthetic beauty. In the postwar period, which saw the fabric of Japanese society change almost as completely as it did after the Meiji Restoration, modernization was again associated with the West, specifically America, and was symbolized by the often crass commercialism that was apparent in Japan.[38] Many liberal Japanese intellectuals of the 1960s became alarmed by the fast postwar economic development, and feared for the very fabric of Japanese society. This movement was ostensibly a “second coming” of earlier Japanese Romanticism. Their fear was understandable, especially given the breadth of social reform that had been ostensibly imposed by outside forces. It is, however, worth exploring the dangers of positing a timeless and “authentic” Japan in direct opposition to modernity by revisiting the path taken by first-wave Romantic ideology in the prewar and wartime eras.

The first-wave Romantics’ positing of a transcendent Japan took a dark turn in the 1930s, when politics and aesthetics merged in fascism. Alan Tansman has demonstrated how the essay “The Bridges of Japan,” written in 1936 by the prominent first-wave Romantic writer Yoshida Yojūrō, influenced a generation of young Japanese men to willingly sacrifice themselves for the nation. Tansman attributes this to Yasuda’s characterization of Japan as an ethereal and elemental force. In Yasuda’s writing, to be Japanese is to be the antithesis of austere, rational, and teleological modernity. Japanese identity is predicated on a connection to an atemporal world that cannot be grasped with rational thought: it is located within the realm of aesthetics and beauty. Tansman argues that this provides the grounds in “The Bridges of Japan” for the ‘spiritual glorification of the shedding of blood.’[39] Yasuda outlined a lack of authentic and subjective Japanese experience for his readers, a spiritual ‘void.’ He then ‘offered a way across [this void] via the bridge’.[40] The absence of Japanese subjectivity was attributed to the “loss of a mythic natural ‘condition,’ when the emperor, the gods, and the people were one.”[41] In this way, Tansman argues, Yasuda merged aesthetic and political to create ‘fascist moments’ that, while not explicitly exhorting self-sacrifice for Japan, nonetheless supplied access to an authentic Japanese experience through submitting oneself to a higher power. The ‘bridge’ was the self-sacrificing, aesthetic, political act, a melding of ‘nature and artifice’ committed in the name of a higher force embodied by the Japanese emperor. At the particular historical moment in which it appeared, “The Bridges of Japan” ultimately blurred the ‘distinctions between art and life and between subject and object, contributed to a poetics of sorrow that extolled the virtues of frailty and defeat, while colluding with a fascist ideology of violence and coercion.’[42] This encouraged ‘a vision of reality as myth,’ a myth in which Japan was destined to express its authenticity through colonial expansion.[43]

I do not intend to suggest here that Suda’s project contains any of the militaristic overtones found in Yasuda’s writing or that this work has the potential to incite violent sacrifice. Instead, I would argue that in Fushi Kaden, Suda is in many ways seeking a similar idea of Japanese essence to that extolled in Yasuda’s writing. The “real” Japan for Suda is an atemporal experience found by rejecting the hyper-modernized urban space in order to once again become close to nature, a state also closely associated with the aesthetic experience of traditional performance. However, as I have argued so far, this photo series is a product of an archive drive, or fever, that also functions in the Foucauldian sense. As an ostensible archive that makes a specific statement about Japanese identity, Fushi Kaden sits within a discursive system that—in an admittedly more extreme form—enabled a dangerous militarism to govern Japanese society in the early twentieth century. For this reason, it is important to note that the nationalistic undertones, most likely unconscious, that are latent in Fushi Kaden point to a dark period in Japanese history. Furthermore, although an effacement of subjectivity is arguably an inevitable consequence of any photographic project, by positing an idea of Japan that is ahistorical and associated with tradition, Fushi Kaden effaces the real diversity of subjective experience in Japanese society and contributes to an ongoing discourse of essentialism.

Conclusion

Thus, Fushi Kaden constitutes an archive of sorts, and in true archival spirit (as a fundamentally repetitive drive) the series is a re-articulation of an oft repeated discourse in Japanese society regarding its origins. It is ultimately an act of self-affirmation whose product functions as part of an ongoing discourse about Japanese identity. This particular discursive statement, in conjunction with the surrealist themes present in Fushi Kaden, gives the sense that a subjective Japanese experience is subterranean, almost unconscious, and somewhat paradoxically only accessible to the modern subject via modern means. Suda’s use of framing, flash, and posing all denote a specific intention to document, with optimum clarity, a Japan he feared was disappearing. He has employed modern methods and aesthetics to uncover a Japanese experience that has historically been posited as binarily opposed to modernity. In this sense, Fushi Kaden reflects the latent impulse in modernity for the archive, to construct a past against which the modern endeavor might be measured. While the clearly subjective nature of Suda’s work speaks against the process of documentation that we might normally associate with the act of archive creation, Fushi Kaden nonetheless reflects what Derrida contends is a fundamental condition of the archive: that the archive is always a look to the future rather than to the past. Archivists work with the future in mind; they assemble a range of documents into an intelligible narrative; an ultimately subjective creation intended for a future audience. Suda has assembled an intriguing range of documents of his own creation aimed at preserving a lost, or at least fast-disappearing, particular Japanese experience. A distinction might be made here between Suda and what we might consider a conventional archivist: his documents are not relics of the past but of his own creation. However, he seemed to view the subjects of his photographs as ultimately belonging to the past, despite their corporal, living presence in front of him. Although they shared Suda’s temporal reality, his principal interest in his subjects was their inherent status as belonging to a symbolic past for which Suda longed. In his missive to document Japanese particularity he simply reflects a specific condition of modernity, a turn to an imagined past in order to affirm one’s present identity.

Ross Tunney is a PhD candidate at the University of Tasmania. His research focuses on issues surrounding national identity and representation in postwar Japanese photography.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Foucault, Michel. The Archeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

- Harootunian, Harry. History's Disquiet: Modernity, Cultural Practice, and the Question of Everyday Life. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

- Hayashi, Shūseki. "Foreword." In Kadensho, 1-12. Japan: Sumiya-Shinobe Publishing Institute 1968.

- Ivy, Marilyn. "Dark Enlightenment: Naitō Masatoshi's Flash." In Photographies East: The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia, edited by Rosalind C. Morris, 229-257. London: Duke University Press, 2009.

- Keene, Donald. Nō: The Classical Theatre of Japan. Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 1975.

- Lamarque, Peter. "Expression and the Mask: The Dissolution of Personality in Noh." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 47, no. 2 (1989): 157-168.

- Nakamura, Yasuo. Noh: The Classical Theater. Translated by Don Kenny. Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1971.

- Orto, Luisa. "Suda Issei." In The History of Japanese Photography, edited by John Junkerman, 361. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Rath, Eric C. "Remembering Zeami: The Kanze School and Its Patriarch." Asian Theatre Journal 20, no. 2 (2003): 191-208.

- Richie, Donald. "Notes on the Noh." The Hudson Review 18, no. 1 (1965): 70-80.

- Ryūichi, Kaneko and Ivan Vartanian. Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and '70s. New York: Aperture, 2009.

- Sorgenfrei, Carol Fisher. Unspeakable Acts: The Avant-Garde Theatre of Terayama Shūji. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2005.

- Tansman, Alan. The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

- Thomas, Julia Adeney. Reconfiguring Modernity: Concepts of Nature in Japanese Political Ideology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Weisenfeld, Gennifer. "Touring Japan-as-Museum: Nippon and Other Japanese Imperialist Travelogues." Positions 8, no. 3 (2000): 747-793.

Notes

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans., Eric Prenowitz (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 26.

Translated as “transmission of the flower of acting style” in Luisa Orto, "Suda Issei," in The History of Japanese Photography, ed. John Junkerman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 361.

Michel Foucault, The Archeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, trans., A.M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), 129.

Kaneko Ryūichi and Ivan Vartanian, Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and '70s (New York: Aperture, 2009), 212.

Carol Fisher Sorgenfrei, Unspeakable Acts: The Avant-Garde Theatre of Terayama Shūji (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2005), 36.

In this, Suda was not alone. Other examples are the work of Domon Ken on village life and temples, Hiroshi Hamaya’s series Snow Land and Kojima Ichiro’s Tsugaru (both taken in remote northern regions of Japan) and Kimura Ihei’s photographs of traditional theater and rural life. All reflected a search for a hypostatized past ‘natural’ state of Japan.

Gennifer Weisenfeld, "Touring Japan-as-Museum: Nippon and Other Japanese Imperialist Travelogues," Positions 8, no. 3 (2000).

Donald Keene, Nō: The Classical Theatre of Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 1975), 11.

Donald Richie, "Notes on the Noh," The Hudson Review 18, no. 1 (1965), 70–71.

Peter Lamarque, "Expression and the Mask: The Dissolution of Personality in Noh." In The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 47, no. 2 (1989).

Eric C. Rath, "Remembering Zeami: The Kanze School and Its Patriarch," Asian Theatre Journal 20, no. 2 (2003).

Shūseki Hayashi, "Foreword." In Kadensho (Japan: Sumiya-Shinobe Publishing Institute, 1968), 8.

Yasuo Nakamura, Noh: The Cassical Theater, trans., Don Kenny (Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1971), 132–36.

Marilyn Ivy, "Dark Enlightenment: Naitō Masatoshi's Flash." In Photographies East: The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia, ed. Rosalind C. Morris (London: Duke University Press, 2009), 232.

Julia Adeney Thomas, Reconfiguring Modernity: Concepts of Nature in Japanese Political Ideology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

This congruence of modernity and “Americanism” can be traced back to the interwar period not only in Japan but also in Europe. See, for example, Harry Harootunian, History's Disquiet: Modernity, Cultural Practice, and the Question of Everyday Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 89–97, 119.

Alan Tansman, The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 49.