Early Twentieth-Century Art Photography in China: Adopting, Domesticating, and Embracing the Foreign

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

An understanding of fine-art photography as it developed in China during the first decades of the twentieth century is still in an initial stage―especially among historians of Western photography who are interested in the transnational spread of the medium.[1] Moreover, historians of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Chinese visual culture are only beginning to acquire a clearer sense of how photography came to be viewed as a medium possessing expressive potential that transcends commercial or practical applications.[2]

As appreciation of that potential developed, photography increasingly attracted an active group of practitioners and champions, and, in the process, reflected many of the overarching aspirations and anxieties of the period’s intellectuals and artists as they sought to transform China into a modern nation capable of standing up both to Western colonizing powers and to Japan. Photography, as a consequence, became one more facet of a larger political and cultural quest to forge and assert a national identity during a period of intense upheaval.

As the title suggests, my aim in this essay is to offer a few comments on what―straightforwardly enough―one might label “Early Chinese Art Photography” and to explore a number of questions prompted by this category of photographs created very much in response to global trends that shaped the medium and which serious photographers in China avidly followed. Aside from the sheer utility of a national and geographic label, might it cause the historian―regardless of his or her nationality―to presume distinct qualities that set apart this body of photographs from those produced elsewhere (in Europe, the United States, Japan) and whose makers similarly declared to be artistic as opposed to commercial? Or, especially because photography as an image-making technology that originated outside of China and was one more feature of the complex of Western modernity embraced and inevitably reshaped by the Chinese, is it a category that, in reality, constitutes an inescapably hybrid cultural phenomenon, as the second half of my title implies? Can Republican-period art photography be well understood only when consistently seen with reference to outside sources as well as the indigenous factors that shaped its emerging character?

To be sure, the process of photography’s adoption by ranks of Chinese practitioners had been flourishing in cities for more than half a century before the concerted effort to promote what its proponents called artistic photography (meishu sheying 美術摄影 or yishu sheying 藝術摄影).[3] The movement among a rapidly growing number of amateur―as opposed to professional―photographers in China to advance the cause of photography as a fine art did not gain momentum until the early 1920s, several decades after this had occurred in Europe and in the United States, and after it had taken place in Japan.[4] The intensifying interest at this time in photography’s artistic potential reflects its complex reception by educated, often reformist-minded Chinese intellectuals. These individuals, many of whom had studied abroad, saw in this foreign-born medium one more means by which they might reposition themselves in relation both to an inherited but problematic tradition and to a “new epoch” (xin shidai 新時代), albeit one fraught with conflict and disorienting tensions.[5] Often mediated through contact with Japan, the effort to embrace Western aesthetic approaches and theories in other mediums occurred during one of the most tumultuous periods in Chinese history and was one facet of a broader, almost cataclysmic cultural shift in the wake of the demise of the Manchu-established Qing dynasty, which had ruled since the mid-seventeenth century and had ended disastrously in 1911.[6]

In the waning years of the Qing dynasty and especially after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95, neo-traditionalist leaders of early reform movements such as Liang Qichao 粱啓超 (1873–1929) called for a defining of “national character” (guoxing 國性) that was grounded in tradition and yet, when realized individually and institutionally, would eradicate endemic weakness and restore the true, still vital Chinese norms of social relationships.[7] Liang also argued, however idealistically, that the renovation of society required a revolution in the arts.[8] That nexus between political reform and the embrace of new modes of art became only stronger during the Republican period (1912–49), finding its most effective advocate in the statesman and educator Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培 (1868–1940). Cai, upon his return from the study of philosophy and art history in Germany, first assumed the position of minister of education and later became president of Beijing University. In Cai Yuanpei’s view, the Kantian ideal of cultivating a capacity for aesthetic response and the love of beauty could foster individual rectitude and undergird a positive and collective transformation of society.[9]

The neo-traditionalists’ efforts may have met with failure, but they paved the way for the more far-reaching influence of the subsequent political and literary “May Fourth Movement” of 1919. The name refers to the spontaneous but large student demonstrations on that day in Beijing at Tiananmen (precursor to the now better-known, more massive Tiananmen demonstration of 1989). It was a demonstration that erupted in response to the news that a then politically powerful clique, representing China at the Paris Peace Conference, had accepted agreements made in secret, thereby enabling Japan to keep its jurisdiction over territory in Shandong province that had been controlled by Germany. The sense that China had again been humiliated triggered the vehement student reaction. As Benjamin Schwartz writes, “Because May Four as an incident occurred at a time when major developments in politics, thought and society were already under way, it was neither a beginning nor a culmination, even though its name is now used to cover an era [1919–25].”[10]

Designating this span of years, the May Fourth Movement has become almost synonymous with an “iconoclastic” uprising against not only the stranglehold of moribund tradition but also the correlated championing of vernacular language (baihua 白話) in literature and all public discourse—as opposed to the archaic language of classical Chinese (wenyan 文言).[11] Moreover, as Leo Ou-fan Lee has pointed out, proponents of the vernacular, among them Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962), “argued that the subject matter of new literature should be broadened to include people in all walks of life and that on-the-spot observations and personal experience . . . should be the prerequisite for writing.”[12]

![Fig. 1: Fang Wenhuai 方文槐 (active 1930s) [or Fang Wenyang 方文揚? or Fang Wenyuan 方文源?], Untitled [Rainy Evening in Shanghai], ca. early 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection. Fig. 1: Fang Wenhuai 方文槐 (active 1930s) [or Fang Wenyang 方文揚? or Fang Wenyuan 方文源?], Untitled [Rainy Evening in Shanghai], ca. early 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000001-ic.jpg) Fig. 1: Fang Wenhuai 方文槐 (active 1930s) [or Fang Wenyang 方文揚? or Fang Wenyuan 方文源?], Untitled [Rainy Evening in Shanghai], ca. early 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection.

Fig. 1: Fang Wenhuai 方文槐 (active 1930s) [or Fang Wenyang 方文揚? or Fang Wenyuan 方文源?], Untitled [Rainy Evening in Shanghai], ca. early 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection. ![Fig. 2: Chen Rentao 陳仁濤 (active 1930s), Rain [Shanghai] 雨, 1933. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 7 (July 1933). Fig. 2: Chen Rentao 陳仁濤 (active 1930s), Rain [Shanghai] 雨, 1933. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 7 (July 1933).](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000002-ic.jpg) Fig. 2: Chen Rentao 陳仁濤 (active 1930s), Rain [Shanghai] 雨, 1933. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 7 (July 1933).

Fig. 2: Chen Rentao 陳仁濤 (active 1930s), Rain [Shanghai] 雨, 1933. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 7 (July 1933). The enunciation and spread of such an advocacy for realism in literature clearly had relevance for all the arts as well. Although Hu Shi never addressed any art other than literature, his critical position seems almost an invitation to photographers to engage in urban street photography―something that, as seen in examples by Fang Wenhuai 方文槐 (active late 1920s–30s) [fig. 1] and Chen Rentao 陳仁濤 (active 1930s) [fig. 2], would not happen until the early and mid-1930s in Shanghai, especially when the Leica, the Contax, and other handheld cameras became available.[13]

The kind of realism advocated in literature by the May Fourth reformers, one suspects, must have struck a chord with those same members of the intellectual elite who had become fascinated by photography. Indeed, an enthusiasm for amateur fine-art photography on the campus of Beijing University arose shortly after the official endorsement of vernacular-language reform by the Ministry of Education in 1921. However, just as the acceptance of the vernacular language as a medium for both practical communication and serious literary expression required leading intellectuals to support its cause, photography as a medium widely regarded for artistic expression required persuasive, influential advocates.

Fig. 3: Members of the Beijing Guangshe 北京光社 (Beijing Light Society), ca. 1928-29 (Liu Bannong is 2nd from right). From Zhongguo Sheying shi (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe,1987; Repr. Taipei: Sheying jia chubanshe, 1990), 153.

Fig. 3: Members of the Beijing Guangshe 北京光社 (Beijing Light Society), ca. 1928-29 (Liu Bannong is 2nd from right). From Zhongguo Sheying shi (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe,1987; Repr. Taipei: Sheying jia chubanshe, 1990), 153. Liu Bannong: Advocate for Photography as Art

One of those advocates was Liu Bannong 劉半農 (1891–1934). Linguist, short-story writer, poet, and, because of his strong support of the use of vernacular language, member of the May Fourth Movement, Liu earned a degree in linguistics from the Sorbonne in 1925 and returned to teach at Beijing University.[14] As a teenager Liu had acquired a rudimentary knowledge of photography, and he developed a passionate interest in it while studying in Paris. After assuming the position at Beijing University, Liu became one of the most active members of the Beijing Guangshe 北京光社 (the Beijing Light Society) [fig. 3], which had been formed in 1923 under the name Yishu xiezhen yanjiuhui 藝術寫真硏究會 (Research Association for Art Photography). By 1924 the group, which at its peak numbered about twenty members, had begun to organize yearly exhibitions that attracted as many as five thousand visitors and in the press occasioned considerable critical discussion about photography’s artistic merits (or lack thereof).[15]

Such debate may have spurred Liu Bannong, in 1927, to publish Bannong tanying 半農談影 (Bannong’s Comments on Photography), the earliest sustained discussion of photography as a fine art in China. Significantly, Liu uses critical terms drawn from the aesthetic discourse about traditional Chinese painting to argue that photography could be an expressive medium and not simply a means to copy whatever might be in front of the camera’s lens. The following passage illuminates how, in framing critical issues, Liu looks to a well-established theoretical model but renovates it, as it were, to make it apt for the new medium of photography:

Photography can be divided into two primary categories: the first category is that which copies [the subject]; the second is that which records [the subject] but does not merely copy it. . . .

Concerning the first category, one must consider the term “copies” in a way that is alive and not dead to its connotations. For instance, to render precisely and without the slightest change a page of ancient calligraphy or a famous painting is to “copy” it. If one photographs an ancient relic or artifact clearly and without distortion, one is copying it. The most important aim in copying is clarity. . . . Thus the term “to render accurately” (xiezhen 寫真) is most apt to use in reference to this category.

Then should the kind [of photography] that does not merely copy be termed “unrealistic” or “unreal”? If one wants to make that claim, I can respond. For my meaning may be summed up by the term “expressive” (xieyi 寫意; literally: “writing or sketching ideas”). . . . [“Expressive”] refers to the photographer using the camera as a vehicle to reveal his inner world of emotions (yijing 意境). . . . When we look at this kind of photograph, we often do not care what the photographer photographed. Rather, based upon our affective response, we experience the photographer’s inner, emotional world. [16]

By using such critical terms as xiezhen 寫真 and xieyi 寫意, Liu deliberately invokes an aesthetic dichotomy that had been articulated by scholar-artists from the late eleventh century onward. Su Shi (1037–1101) 稣軾, the great Northern Song–dynasty poet, calligrapher, and amateur painter, used the term xiezhen 寫真 to refer to “the depiction of details of surface,” which could detract from what he regarded as true painting.[17] Although Su did not specifically use the term xieyi 寫意, he did advocate the expression of the painter’s “mind” or “ideas” (yi 意), thus laying the foundation for the kind of painting practiced by scholars (later known as wenren hua 文人畫), which eschewed the detailed naturalism of professional and court painters. Liu Bannong, in trying to promote consideration of photography as an expressive art, could not have been more astute from a rhetorical standpoint than in this implicit reference to the pivotal period when painting was being elevated by Su Shi and members of his circle to assume an equal place alongside poetry and calligraphy as an art of self-cultivation.

During the fourteenth century, scholar-painters of the Yuan dynasty began to use the term xieyi 寫意 to distinguish their painting, which was often highly calligraphic, personally expressive, and accompanied by inscriptions, from that of professionals who were forced to paint in a manner that conformed to their patrons’ requirements.[18] By the early twentieth century, the use of xieyi 寫意 had become essentially shorthand for any artist who wanted to indicate that he was not obligated to consider commercial pressures―whether or not this was true.[19] Liu pointedly adopted such terms to make the case that the kind of photography he and the other members of the Guangshe (the Beijing Light Society) practiced was qualitatively different from that produced for purely informational or commercial purposes or by professional studios restricted by the demands of their clients.

![Fig. 4: Wang Mengshu 汪孟舒 (active 1920s), The Spirit of Yunlin’s [Ni Zan’s] Painting 雲林畫意, ca. 1927. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library. Fig. 4: Wang Mengshu 汪孟舒 (active 1920s), The Spirit of Yunlin’s [Ni Zan’s] Painting 雲林畫意, ca. 1927. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000004-ic.jpg) Fig. 4: Wang Mengshu 汪孟舒 (active 1920s), The Spirit of Yunlin’s [Ni Zan’s] Painting 雲林畫意, ca. 1927. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library.

Fig. 4: Wang Mengshu 汪孟舒 (active 1920s), The Spirit of Yunlin’s [Ni Zan’s] Painting 雲林畫意, ca. 1927. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library. ![Fig. 5: Chen Wanli 陳萬里 (1892-1969), After Ni Yunlin’s [Ni Zan]Small Landscape of Pines & Rocks (On the Path at Panshan to the East of Beijing) 仿倪雲林松石小景 (京東盤山道中), ca. 1919-1924. Gelatin silver print. From Chen Wanli, Da Feng ji (Great Wind Collection), Courtesy of Chen Shen. Fig. 5: Chen Wanli 陳萬里 (1892-1969), After Ni Yunlin’s [Ni Zan]Small Landscape of Pines & Rocks (On the Path at Panshan to the East of Beijing) 仿倪雲林松石小景 (京東盤山道中), ca. 1919-1924. Gelatin silver print. From Chen Wanli, Da Feng ji (Great Wind Collection), Courtesy of Chen Shen.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000005-ic.jpg) Fig. 5: Chen Wanli 陳萬里 (1892-1969), After Ni Yunlin’s [Ni Zan]Small Landscape of Pines & Rocks (On the Path at Panshan to the East of Beijing) 仿倪雲林松石小景 (京東盤山道中), ca. 1919-1924. Gelatin silver print. From Chen Wanli, Da Feng ji (Great Wind Collection), Courtesy of Chen Shen.

Fig. 5: Chen Wanli 陳萬里 (1892-1969), After Ni Yunlin’s [Ni Zan]Small Landscape of Pines & Rocks (On the Path at Panshan to the East of Beijing) 仿倪雲林松石小景 (京東盤山道中), ca. 1919-1924. Gelatin silver print. From Chen Wanli, Da Feng ji (Great Wind Collection), Courtesy of Chen Shen. Given that Liu applied this kind of aesthetic discourse to photography, it comes as almost no surprise that at least two members of the Beijing Light Society, Wang Mengshu 汪孟舒 (active late 1920s) and Chen Wanli 陳萬里 (1892–1969),[20] made photographs that allude to the fourteenth-century scholar-painter Ni Zan 倪瓉 (1301–1374), one of the four great masters of the Yuan dynasty and much associated with the expressive ideal of xieyi [figs. 4 and 5]. Indeed, the titles Wang and Chen gave to their pictures refer to Ni by his sobriquet, Yunlin 雲林 (Cloud Forest).

Ni Zan, a scholar and aesthete who was forced for decades to live as a floating wanderer on a houseboat as he fled from the reach of Mongol rule, became famous for his spare, abstract, calligraphic compositions that rehearsed again and again the theme of an unpeopled realm of reclusion [fig. 6].[21] In the centuries after Ni’s death, the manner became increasingly formulaic but was widely imitated by later scholar-artists, as exemplified by the seventeenth-century artist Cheng Jiasui’s 程嘉燧 (1565–1643) Pavilion in an Autumn Grove, from 1630 [fig. 7].[22]

Fig. 6: Ni Zan 倪瓉 (1301-1374), The Rongxi Studio 容膝齋圖軸, 1372. Hanging scroll, ink on paper. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Fig. 6: Ni Zan 倪瓉 (1301-1374), The Rongxi Studio 容膝齋圖軸, 1372. Hanging scroll, ink on paper. National Palace Museum, Taipei.  Fig. 7: Cheng Jiasui 程嘉燧 (1565-1643), Pavilion in an Autumn Grove, 1630. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Gift of Arthur M. Sackler (S1987.0212).

Fig. 7: Cheng Jiasui 程嘉燧 (1565-1643), Pavilion in an Autumn Grove, 1630. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Gift of Arthur M. Sackler (S1987.0212). Centuries later, for photographers such as Wang Mengshu and Chen Wanli, the “Ni Zan mode” afforded immediate indication of a seriousness of purpose, however burdened these slight pictures may seem to later viewers. Wang’s picture especially echoes the most stripped-down version of Ni’s late practice[23] and its subsequent rendition by other seventeenth-century artists, among them Zheng Min 鄭旼 (active in the latter half of the seventeenth century).[24] But one also wonders whether Wang or Chen, despite the pictures’ titles, which so avow each man’s indebtedness to Ni Zan, had seen examples of minimalist landscapes done by either Western or Japanese pictorialist photographers, who favored the elimination of distracting detail for the sake of dreamy mood and atmospheric effect.[25]

International Pictorialism and the Chinese Amateur Photographer

There is no question that by the early 1930s European photographic publications such as Das deutsche Lichtbild (the German Annual of Photography) and the British annual Photograms of the Year were in circulation in Shanghai, though determining which ones were available in Beijing during the late 1920s requires a further search for scattered clues.[26] Nevertheless, the impact that international pictorialism exerted on amateur Chinese photographers is unmistakable. Liu Bannong undoubtedly encountered it while studying in Paris (and briefly in London), and it is possible that he returned with French and British photographic publications featuring pictorialist works. Indeed, two of the three editions of Bannong tanying (Bannong’s Comments on Photography) that I have seen include a small selection of landscape and genre scenes by obscure French and British pictorialist photographers.

Fig. 8: Liu Bannong 劉半農 (1891-1934), The Dance 舞, 1926. Gelatin silver print. From Zhongguo Sheying shi (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe,1987; Repr. Taipei: Sheying jia chubanshe, 1990), 192.

Fig. 8: Liu Bannong 劉半農 (1891-1934), The Dance 舞, 1926. Gelatin silver print. From Zhongguo Sheying shi (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe,1987; Repr. Taipei: Sheying jia chubanshe, 1990), 192.  Fig. 9: Liu Bannong 劉半農, Slanting Rays of Sun 夕照

照, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Beijing Guangshe nianjian, No. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library.

Fig. 9: Liu Bannong 劉半農, Slanting Rays of Sun 夕照

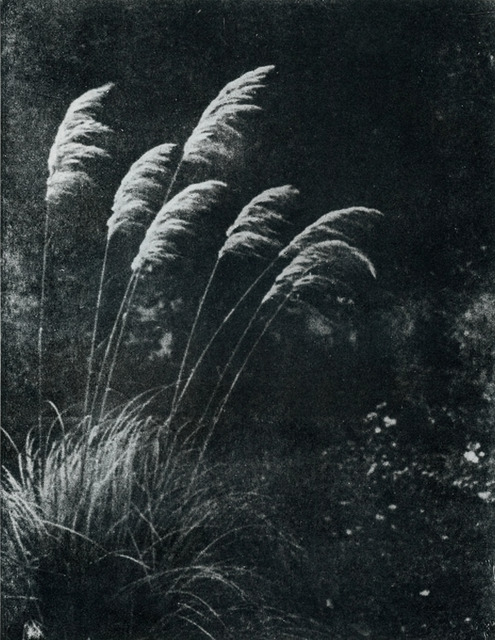

照, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Beijing Guangshe nianjian, No. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Municipal Library. Liu’s own photographs, as evidenced by those published in the two Guangshe (Beijing Light Society) annuals, adhere to a pictorialist aesthetic in their interest in mood and in the patterned effect of last light [figs. 8 and 9].[27] Unlike Wang Mengshu and Chen Wanli, who relied on rather lofty allusions to give their images consequence beyond what is pictured, Liu is daring and allows the changing light itself to direct his lens toward somewhat pedestrian subject matter—grasses or relatively nondescript architecture, for example. In framing such subjects, he asserts their significance because of an emotional response he has felt and wants to communicate to viewers who might also respond―that is, if we are to see his pictures as consonant with his theory.

Fig. 10: Liu Bannong 劉半農, Stillness 靜, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Beijing Guangshe nianjian, No. 2 (1929).

Fig. 10: Liu Bannong 劉半農, Stillness 靜, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Beijing Guangshe nianjian, No. 2 (1929).  Fig. 11: Liu Bannong 劉半農, All Heading into the Light 齊 向光明中去, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe nianjian, No. 2 (1929).

Fig. 11: Liu Bannong 劉半農, All Heading into the Light 齊 向光明中去, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe nianjian, No. 2 (1929). The selection of Liu’s photographs that appear in the second annual, although one cannot assume that they date from a year later, reflects an interest in combining landscape and genre scenes, as seen in his study of boats moored along the shore and in his view, beyond brightly sunlit water, of boats in the distance ferrying passengers [figs. 10 and 11]. In these two images Liu has framed a motif—boats on the water—that had an enduring history not only in painting but also in nineteenth-century Chinese photography (whether the pictures were made by Westerners or by Chinese photographers); indeed, boats on the water became one of the most popular subjects, and inevitably something of a cliché, among amateur photographers throughout the 1930s.[28] Often Chinese photographers, for example the prominent Shanghai commercial artist and amateur photographer Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔 (1896–1989) in a mid-1930s photograph of boats on a diagonal stretch of river [fig. 12], employ this subject in order to make what seems a deliberate reference to its long history as a motif in poetry and in traditional painting, as seen in an album leaf by the Ming-dynasty painter Qiu Ying 仇英 (1494–1552) [fig. 13].[29]

![Fig. 12: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔 (1896-1989), Untitled [Boats on the River], ca. 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection. Fig. 12: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔 (1896-1989), Untitled [Boats on the River], ca. 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000012-ic.jpg) Fig. 12: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔 (1896-1989), Untitled [Boats on the River], ca. 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection.

Fig. 12: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔 (1896-1989), Untitled [Boats on the River], ca. 1930s. Gelatin silver print. Private Collection.  Fig. 13: Qiu Ying 仇英 (1494-1552), from Six Scenes in Song & Yuan Styles 臨宋元六景, no. 1 (detail). Album of six leaves, ink & colors on silk. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Fig. 13: Qiu Ying 仇英 (1494-1552), from Six Scenes in Song & Yuan Styles 臨宋元六景, no. 1 (detail). Album of six leaves, ink & colors on silk. National Palace Museum, Taipei. Given the remarks quoted above, however, Liu may have been far less interested—if at all―in referring to a model from traditional Chinese painting in these pictures; rather, it seems he sought to capture either the geometry of perceived pattern or the gorgeous effect of shimmering light on a body of water—qualities of image that the camera, conjoining realism and poetic perception, could render with compelling effect. For similar reasons, the subject was also a magnet for many Western photographers whom we now group under the label of pictorialism and who worked several decades before their Chinese counterparts.[30]

Because of Liu’s support of the use of vernacular language, one suspects that he would have been less enthusiastic about a type of photography that, although expressive in a rarefied way, deliberately referred to scholarly models from indigenous painting. Indeed, in the coda to Bannong tanying (Bannong’s Comments on Photography), Liu makes a statement that comes surprisingly close to a modernist position:

Many people believe that photography imitates painting. This truly is a big mistake. At least I, for one, am unwilling to advocate such a thing. This is because painting is painting and photography is photography. Although the two share some similarities, each has its own special qualities and in reality cannot imitate the other. If one were to say that the aim of photography is to imitate painting, it would be better just to study painting.[31]

In the end, Liu never addresses which models—if any—Chinese photographers should follow, but like other May Fourth reformers, he appears to stress the value of self-expression and direct engagement with experience. Moreover, in accord with Hu Shi and other May Fourth writers, Liu brought a nationalist fervor to his championing of photography, arguing that it could be one more means for the assertion of a new and national identity. In his 1928 preface to the Beijing Light Society’s second annual, published the following year, Liu vehemently articulates this ideal:

[When] I consider photography—this thing—no matter if others respect it as an art or revile it as nothing more than a dog’s fart, as [something] we are already doing; thus always we should not forget that there’s a self [involved with it] and, even more so, we should not forget that we are Chinese. Every day we may hold up reverently Kodak’s “Monthly” or the British Annual, or the American Annual or even the “small devils’” [Liu is referring to the Japanese] Annual, and consider these as the originators of the craft we practice and therefore in this or that way imitate them, modeling ourselves after them until our hair turns white and piles of photographs fill up large trunks. Isn’t that good enough? However, in my view, [such an approach] doesn’t lead to anything. We need to use the camera to express fully our own personalities and the distinctive sentiments and refinements of the Chinese people [zhongguoren teyoude qingqu yu yundiao 中國人特有的情趣與韵凋], thus enabling our works to establish their own kind of character different from that of other countries. Only then will our efforts not have been wasted and we will not have given uselessly our money to Kodak and Agfa.[32]

Despite expressions of such nationalist fervor, many of the photographs produced by members of the Beijing Light Society and those of subsequent societies in Shanghai, to which the center of photographic activity shifted at the end of the 1920s, reflect either an outright but adroit mimicking of international pictorialism or a blending of it with subject matter drawn from traditional Chinese painting. Both strategies served to domesticate and, to varying degrees, produce a creative response to a foreign style. Based on what was produced by the early amateur photographers in Beijing, we might identify two subsets under the category of early Chinese art photography: “Transplanted International Pictorialism” and “Chinese-Inflected Pictorialism,” the latter exemplified by Chen Wanli’s and Wang Mengshu’s photographs discussed above.

Perhaps even more than Liu’s pictures, an example of transplanted international pictorialism is Sun Zhongkuan’s 孫仲寛 Winter Stream, which appeared in the Beijing Light Society’s first annual, published in 1928 [fig. 14]. Sun’s picture suggests he had seen and learned from Western (or Japanese) pictorialist photographers who experimented with stark landscape compositions that became almost abstract studies of plane and line.

Fig. 14: Sun Zhongkuan 孫仲寛 (active 1920s), Winter Stream 寒溪. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Muncipal Library.

Fig. 14: Sun Zhongkuan 孫仲寛 (active 1920s), Winter Stream 寒溪. Gelatin silver print. From Guangshe Nianjian (Annual of the Beijing Light Society), no. 1 (1928). Courtesy of the Shanghai Muncipal Library.  Fig. 15: Gustav E.B. Trinks (1871-1967), Colored Shadows (Farbige Schatten), 1902. Photogravure. Courtesy of Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg.

Fig. 15: Gustav E.B. Trinks (1871-1967), Colored Shadows (Farbige Schatten), 1902. Photogravure. Courtesy of Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. In Europe and the United States, this kind of pictorialist approach to landscape, as noted by historians of Western photography, was informed by the widespread Japonisme of the period.[33] In China, as art photographers in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai responded to international pictorialist photography, a similar interest in spare, almost abstract pictorial design that had its roots in Japanese woodblock prints appears in photographs. This phenomenon constitutes another aspect of the complex ways in which Chinese visual culture, beginning well before the Republican period, reflected Japanese models―whether directly or obliquely and whether or not it was acknowledged―or reflected, as in this instance, a melding of Japanese and Western precedent.[34] Sun Zhongkuan’s Winter Stream, like Hamburg-based Gustav E. B. Trinks’s (1871–1967) perhaps technically more accomplished Colored Shadows (Farbige Schatten) [fig. 15] from two decades earlier, in 1902, proclaims its romantic lyricism and asserts its status as an aesthetic vision.[35] That vision relies, nevertheless, on knowledge and appropriation of a foreign model.[36]

Fine Art Photography in 1930s Shanghai

When several of the most influential members of the Beijing Light Society moved southward, the group lost its momentum. Its legacy, however, laid the foundation for a succession of amateur photography societies that arose in Shanghai at a time of tremendous vitality in the visual and literary arts. Just as in Beijing during the May Fourth era, this vitality occurred in part because of intensifying upheavals in Shanghai’s social and political fabric, as intellectuals and activists demanded reform and as an expanding, well-educated middle class sought to embrace Western modernity. Photography helped fuel the construction and dissemination of what has been termed modernity’s “cultural imaginary” in Shanghai.[37]

For almost a decade, until Japan’s invasion of the city in August 1937, Shanghai gave rise to important amateur fine-art photographic groups such as the Zhonghua sheying xueshe 中華摄影學社 (the China Photographic Study Society), which formed in 1928 and was better known by its abbreviated name, Huashe 華社, and the somewhat more avant-garde Heibai yingshe 黑白影社 (the Black & White Photographic Society). Both groups, whose members were drawn more from publishing and commerce than from academe, organized well-attended exhibitions and supported the publication of magazines and exhibition catalogues. Other prominent photography magazines, such as Zhonghua Sheying Zazhi 中華摄影雜誌 (The Chinese Journal of Photography), Chenfeng 晨風 (Dawn Wind), and Feiying 飛鷹 (Flying Eagle), arose in quick succession or, in some cases, overlapped.[38] These publications showcased the work of leading amateurs: Hu Boxiang, mentioned earlier, Lang Jingshan (Long Chin-san) 郎静山 (1892–1995), Chen Chuanlin 陳傳霖 (1897–1945), Lu Shifu 盧施福 (1898–1983), Wu Zhongxing 吳中行 (1899–1976), and Jin Shisheng 金石聲 (1910–2000), names that―except perhaps for Lang Jingshan―remain virtually unknown to most historians of photography.[39] Feiying (Flying Eagle) was the last of the high-quality photography journals of the Republican era.[40] Its twentieth issue had already been printed and was ready for binding when it was destroyed in the bombing of the city by the Japanese.

Here I offer only a few generalizations about the photographs that appear in the pages of these magazines and exhibition catalogues. On the whole, one sees not only a strong continuity with but also a departure from trends apparent among the Beijing amateurs of the late 1920s. Broadly speaking (in no way is this absolute), there is a shift in Shanghai during the mid-1930s from pictures that adhere to the aesthetic values of pictorialism, or a Chinese-inflected version of it, to ones that evidence a growing awareness of that other international movement exerting an impact on all the visual arts and specifically on photography—modernism. Sometimes even the same photographer, such as Lang Jingshan, produced images that either adhered to the earlier, more conservative lyricism of pictorialism or adopted the newer visual strategies and subject matter associated with modernism [figs. 16a and b].[41] His Architectural Study of the “Grand” Cinema in Shanghai, an Art Deco building that attracted the attention of quite a few photographers, torques the frame and slices through the structure to evoke the sense of a passerby turning his or her head to look up at the imposing geometry of the theater’s façade.[42]

![Fig. 16a: Lang Jingshan 郎静山 (1892-1995), Returning Woodcutter on a Mountain Path 山徑歸樵, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 21. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui. Fig. 16a: Lang Jingshan 郎静山 (1892-1995), Returning Woodcutter on a Mountain Path 山徑歸樵, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 21. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000016-ic.jpg) Fig. 16a: Lang Jingshan 郎静山 (1892-1995), Returning Woodcutter on a Mountain Path 山徑歸樵, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 21. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui.Fig. 16b: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Architectural Study 建築 [The “Grand” Cinema, Shanghai], ca. 1935. Toned gelatin silver print. From Chenfeng (Dawn Wind), no. 10 (May, 1935).

Fig. 16a: Lang Jingshan 郎静山 (1892-1995), Returning Woodcutter on a Mountain Path 山徑歸樵, 1933. Gelatin silver print. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 21. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui.Fig. 16b: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Architectural Study 建築 [The “Grand” Cinema, Shanghai], ca. 1935. Toned gelatin silver print. From Chenfeng (Dawn Wind), no. 10 (May, 1935). ![Fig. 17: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print from combined negatives. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 31. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui. Fig. 17: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print from combined negatives. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 31. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui.](/t/tap/images/7977573.0003.204-00000017-ic.jpg) Fig. 17: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print from combined negatives. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 31. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui.

Fig. 17: Lang Jingshan 郎静山, Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks 春樹奇峰, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print from combined negatives. Source: Sheying dashi Lang Jingshan [Lang Jingshan: Master Photographer] (Beijing: Zhongguo Sheying chuban she, 2003), plate 31. Courtesy of Taipei Lang Ching-shan i-shu wen-hua fa-chan hsueh-hui. But Lang, who came from a family of successful artists, is far more famous for his photographs that imitate, often through combining two or three negatives, traditional Chinese painting—especially landscapes that echo the monumental landscape painting of the Northern Song dynasty. Thus, Lang’s Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks may serve to typify the continuation among fine-art photographers in Shanghai of the attempt to evoke aspects of Chinese painting in photographic form, whether in the expressive mode of literati painting (xieyi) or that of the more detailed naturalism (xiezhen) associated with court and professional painters [fig. 17].[43] Hu Boxiang’s photograph of boats on a river, mentioned above, and his Returning at Dusk, which captures a lone donkey rider amid a mountainous terrain, also treat subjects that had immediate associations with traditional landscape painting. The latter, because of its soft focus and apparently gold or sepia toning, especially recalls earlier Song and Yuan models [fig. 18].

Fig. 18: Hu Boxiang 胡伯 翔, Returning at Dusk 石城晚歸, ca. 1930. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi, No. 3 (August 1932), 98. Gelatin silver or gum-bichromate print.

Fig. 18: Hu Boxiang 胡伯 翔, Returning at Dusk 石城晚歸, ca. 1930. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi, No. 3 (August 1932), 98. Gelatin silver or gum-bichromate print. Hu Boxiang, however, was somewhat like Lang Jingshan in that he did not photograph in only a single manner. A successful painter of calendar pictures for the British American Tobacco Company (BAT), Hu also served as the editorial adviser to The Chinese Journal of Photography and published photographs in a number of Shanghai’s prominent illustrated periodicals. He produced photographs that are unmistakably pictorialist in character (i.e., exhibiting a soft focus) but which also, in some instances, depict subject matter not from the realm of Chinese painting.[44]

Fig. 19: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔, Threshing Wheat 打麥, ca. 1936. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 11 (June, 1936).

Fig. 19: Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔, Threshing Wheat 打麥, ca. 1936. Gelatin silver print. From Zhonghua sheying zazhi (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 11 (June, 1936). Hu’s Threshing Wheat, from the mid-1930s [fig. 19], exemplifies this other side of his photographic interests and, like Sun Zhongkuan’s Winter Stream, discussed earlier, falls into the subset I termed “transplanted international pictorialism.” Threshing Wheat’s theme of rural labor, kept at a romantic distance by Hu’s avoidance of a sharply focused lens, recalls the work of a long lineage of pictorialists that includes Peter Henry Emerson (1856–1936), whose sympathetic but still romanticized images of labor seem to be echoed in Hu’s picture.[45] Could Hu Boxiang have seen Emerson’s photographs? More than many of the other Chinese amateur photographers working in Shanghai, Hu— because of his employment with BAT—probably had extensive contact with foreigners, who might have shown or provided him with British photographic publications.[46]

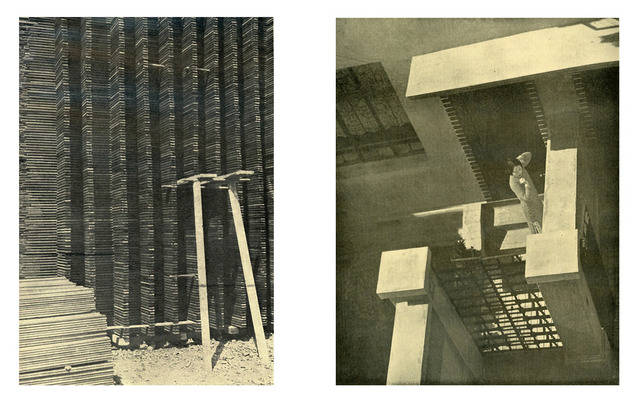

The photographic modernism that appeared in Shanghai in the mid-1930s existed alongside the continuing interest in a pictorialist aesthetic with varying degrees of reference to the tradition of Chinese painting. Indeed, certain key members of the Black & White Photographic Society wrote about their discovery of German publications such as Foto-Auge (1929), which featured the work of, among others Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), and Albert Renger-Patzsch’s (1897–1966) Die Welt ist schőn (1928).[47] Reflecting this awareness of the “new photography,” Shanghai photographers began to produce their own radically new pictures, whether self-portraits, figure studies, still lifes, or views of architecture, as seen in Shui Fuping’s 水浮萍 (active 1930s) Planks and Ye Qianyu’s 葉淺予 (1907–1995) New Residence [figs. 20a and b].

Fig. 20a: Shui Fuping 水浮萍 (active 1930s), Planks 四十六板板, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 1 (1934).Fig. 20b: Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-1995), New Residence 新居, ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 2 (1935).

Fig. 20a: Shui Fuping 水浮萍 (active 1930s), Planks 四十六板板, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 1 (1934).Fig. 20b: Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-1995), New Residence 新居, ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 2 (1935). These Shanghai photographers abandoned conventional pictorial structure—whether inspired by Chinese tradition or Western—by focusing on abstract patterns found in the everyday world or producing unexpected visual configurations achievable by manipulating the camera’s viewpoint. Their aim, like that of the European photo-modernists whose works inspired them, was to mirror a new urban and more mechanized reality, the kind of world that could also be seen to reflect China’s definite break with its stultifying imperial past.[48] In these modernist photographs, we see reflected the new Shanghai, with its factories, gas stations, steel bridges, and shop-window displays. These urban themes, which seem a universe away from pictorialist landscapes, are well examined in Luo Gusun’s 羅榖蓀 Bridge [fig. 21a] , with its dense pattern of girders that dwarf the pedestrians, and Shang Fu’s 尚甫 Melody of Lines [fig. 21b] , with its compositional structure that momentarily disorients the viewer; the photographer has tilted the camera to make more strange the sunlit-striped curbside of what is either a gas station or an automobile showroom. (In the picture’s depths, there seems to be a fancy automobile behind a large plate-glass window.)[49]

Fig. 21a: Luo Gusun 羅榖蓀 (active 1930s), Bridge 橋梁, ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 2 (1935).Fig. 21b: Shang Fu 尚甫 (active 1930s), Melody of Lines 調線, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print. From Chenfeng, no. 8 (September 1934).

Fig. 21a: Luo Gusun 羅榖蓀 (active 1930s), Bridge 橋梁, ca. 1935. Gelatin silver print. From Heibai yingji, No. 2 (1935).Fig. 21b: Shang Fu 尚甫 (active 1930s), Melody of Lines 調線, ca. 1934. Gelatin silver print. From Chenfeng, no. 8 (September 1934). Whereas Lang Jingshan merely flirted with modernism, slightly younger Chinese photographers were beginning to commit themselves to the use of the camera to record images that one might say truly support Liu Bannong’s statement that photography is categorically different from painting, a view expressed in his treatise of 1927 and which I quoted above. By participating in a worldwide movement and mimicking European models, such Chinese photographic modernists sought both self-expression and a means to convey an increasingly hybrid reality of Shanghai, with its mix of indigenous and Western elements—much as is the city today. Embracing an imported modernist spirit and viewpoint, amateur art photographers could demonstrate their own up-to-dateness and at the same time portray China’s industrial accomplishment, albeit largely concentrated in an urban setting and only in small sections of the city at that. Nevertheless, akin to Chinese pictorialist photographers such as Sun Zhongkuan and the many others whose works hewed to the Western pictorialist model, these modernists also practiced an art of appropriation.

If the historian is pressed to identify or locate distinct characteristics that separate such pictures from their European counterparts, perhaps he or she can point only to small details glimpsable within the pictures that serve as telltale markers of ethnic specificity and identifiable locale. Possibly no modernist Chinese art photographer, because of the very trajectory and emphasis of modernism itself, could create images that signal more enduring cultural values apart from those embodied by a society (at least in a city like Shanghai) increasingly fueled by industrialization and budding consumerist capitalism―especially given that the social and political reality of the Republican period was fragile and fraught with underlying urgency.[50]

Although vigorously alive with activity and promise, this brief span of years seems to have been too short for art photographers in China to produce radically distinctive approaches to this adopted but by then thoroughly established medium, one that might in turn engender appropriation by others. Now, in a far more globalized art world and when postmodern photography is so often combined with other mediums, an ascendant China may yet be―or may already be―the progenitor of transnational trends in photographic expression and meaning that ripple outward from Shanghai or Beijing or some other Chinese city.

Coda: The Case of Donald Mennie

I offer a coda to this brief consideration of Republican-period fine-art photography, which was such a complex cultural surge of adoption and appropriation, by referring to the example of Donald Mennie (1899?–1941). Mennie’s photographs also challenge tidy national and stylistic categorizations. Although pictorialist in style, they represent something of an almagam of appropriated themes and poetic references.

Mennie, who probably came from Scotland, worked first in Beijing and then, for as long as perhaps two decades, in Shanghai as the managing director of the British pharmaceutical company A.S. Watson; it seems that he lived in China for almost his entire adult life,[51] and all of his known photographs were made in China. Although next to nothing is known about his life, it is evident that as an amateur photographer, Mennie possessed immense skill (and considerable ambition), publishing in China a series of books that were illustrated with exquisite photogravures.[52] Many of the images in these books show Mennie’s unalloyed allegiance to a pictorialist aesthetic. Through his use of tipped-in “Vandyck photogravures” and his strong interest in capturing scenery little affected by modern change, it is as if Mennie was consciously emulating what John Thompson had done in China more than fifty years earlier or what Peter Henry Emerson had accomplished in England through his study of the Norfolk Broads in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

But Mennie also appears to have assimilated an appreciation of traditional Chinese painting and poetic subject matter that enables his images to compete, in their sheer evocative quality, with many of those by Lang Jingshan—arguably the most well-known practitioner of what I have termed “Chinese-inflected Pictorialism”—or by Hu Boxiang and many lesser-known Chinese photographers who published their works in Shanghai photographic periodicals and illustrated magazines. Like his Chinese counterparts, Mennie frequently trained his lens on waterways and the boats plying them. And, like Chinese photographers, Mennie sometimes quotes or alludes to lyric poetry in choosing titles for his images. His photograph entitled Ere the mist had altogether yielded to the sun (sic), which takes a line from Wordsworth’s “Point Rash-Judgment,” could easily be mistaken for one by a Chinese photographer of the period [fig. 22].[53] Indeed, Peng Wangshi’s 彭望軾 (active 1920s) photograph Stirring the Water, Breaking the Cold Stillness, whose title also likely borrows a line from a poem, corresponds to Mennie’s in both its theme and its strongly atmospheric pictorialism [fig. 23].[54]

Fig. 22: Donald Mennie (1899?-1941), Ere the mist had altogether yielded to the sun, ca. 1920s. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection.

Fig. 22: Donald Mennie (1899?-1941), Ere the mist had altogether yielded to the sun, ca. 1920s. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection.  Fig. 23: Peng Wangshi 彭望軾 (active 1920’s), Stirring the Water, Breaking the Cold Stillness 激水破寒寂. Gelatin silver print? From Tianpeng (The China Focus), vol. III, no. 1 (July 1, 1928).

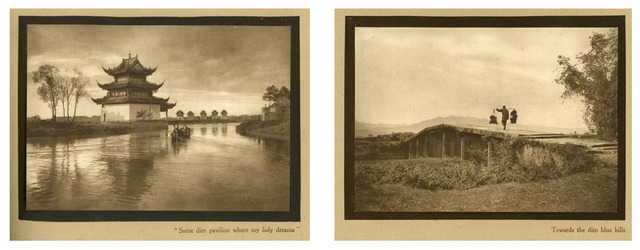

Fig. 23: Peng Wangshi 彭望軾 (active 1920’s), Stirring the Water, Breaking the Cold Stillness 激水破寒寂. Gelatin silver print? From Tianpeng (The China Focus), vol. III, no. 1 (July 1, 1928). In comparing the two and in thinking of Liu Bannong’s nationalistic, if vague, injunction in Bannong tanying (Bannong’s Comments on Photography) that Chinese photographers use the camera to express “the distinctive sentiments and refinements of the Chinese people,” one might ask: Hasn’t Mennie, a long-time resident of China who apparently was keenly responsive to a time-honored subject in Chinese painting and poetry, done that as well―even though he was not Chinese? A master of romantic scenic views, when Mennie photographed the streets of Beijing or unidentified villages of the Songjiang area (a district within present-day Shanghai), he allowed hardly a hint of the social and industrial transformation that was occurring in China to intrude upon the selected compositions—or he assiduously avoided subject matter that would have revealed such change.[55] Instead, Mennie invites the viewer to enter a lyrical vision of the Chinese countryside, the travelers passing through it, and its exotic, grand architecture of a bygone era [figs. 24a and b].

Fig. 24a: Donald Mennie, Some dim pavilion where my lady dreams. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection.Fig. 24b: Donald Mennie, Towards the dim blue hills. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection.

Fig. 24a: Donald Mennie, Some dim pavilion where my lady dreams. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection.Fig. 24b: Donald Mennie, Towards the dim blue hills. Photogravure. From Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures illustrating Chinese life and surroundings. Private Collection. Mennie’s audience, likely other foreigners in China who purchased or received his books as keepsakes, no doubt appreciated the manner in which his photographs convey a poetic aesthetic and impart to the subjects, even when ragged and toiling, a mood of timeless tranquility. Certainly nowhere to be seen is evidence of the tumultuous disintegration of the Qing dynasty and the lurching efforts to found a republic. On one level, his images reflect a colonizer’s privileged romanticism, but their aestheticism may be no more escapist than the great number of photographs produced by equally serious Chinese amateurs who, like Mennie, were inspired by international pictorialism, or the particular inflection it received in China, and eschewed any hint of modernist experimentation.

Richard K. Kent teaches Asian art history and the history of photography at Franklin & Marshall College. His current research concerns various facets of twentieth-century Chinese photography. Recent publications include “Fine Art Photography in Republican Period Shanghai: From Pictorialism to Modernism” (in Bridges to Heaven: Essays on East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong, Princeton, 2011); and “Reclaiming Documentary Photography” (in Jerome Silbergeld, Humanism in China: A Contemporary Record of Photography, catalogue to an exhibition at China Institute, New York, 2009).

Notes

I want to thank Andrea Noble, Jonathan Long, and Edward Welch, the organizers of the stimulating 2007 international conference “Locating Photography: Between the Local, the National, and the Universal,” at the Durham Centre for Advanced Photography Studies, St. John’s College, University of Durham, where I presented an earlier version of this essay. In Beijing, where I continued to do research for it, Chen Shen offered unfailing help and insight. I also thank both an anonymous reader and Sandra Matthews, the editor of this journal, for comments that helped me improve it. Judith Chien, once again, has provided astute editorial advice and I thank her. I gratefully acknowledge funding for faculty research from Franklin & Marshall College that supported this project.

To date there is a small―but now growing―number of publications on the topic. In Chinese, three key sources are surveys of photography: Hu Zhichuan 胡志川, Ma Yunzeng 馬運增, Chen Shen 陳申, Qian Zhangbiao 錢章表, and Peng Yongxiang 彭永祥, Zhongguo sheying shi: 1840–1937 中國摄影史 [History of Chinese Photography; hereafter ZGSYS] (Beijing: Zhongguo sheying chubanshe, 1987; Repr. Taipei: Sheying jia chubanshe, 1990); Huang Shaofen 黄紹芬, ed., Shanghai sheying shi 上海摄影史 [History of Photography in Shanghai; hereafter SHSYS] (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe, 1992); and Su Zhigang 宿志刚, Lin Li 林黎, et al., eds., Zhongguo sheying shilue 中国摄影史略 [Historical Outline of Chinese Photography] (Beijing: Zhongguo wenlian chubanshe, 2009). More recently, a monographic study devoted to the history of artistic photography has appeared: Chen Shen 陳申 and Xu Xijing 徐希景, Zhongguo sheying yishu shi 中国摄影艺术史 [History of Chinese Photographic Art] (Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2011).

In English, this period’s photography or select photographers are briefly mentioned in Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, “Shanghai Modern,” in Shanghai Modern 1919–1945, edited by Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker, Ken Lum, Zheng Shengtian (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2004), 39 [on Long Chin Shan {Lang Jingshan}]; Ellen Johnston Laing, Selling Happiness: Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early Twentieth-Century Shanghai (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004), 177–78 [on Hu Boxiang]; and Christopher Phillips, “The Great Transition: Artists’ Photography and Video in China,” in Christopher Phillips and Wu Hung, Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China (Chicago and New York: Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, and the International Center of Photography, 2004), 40–41. For a more in-depth study, see the author’s “Fine Art Amateur Photography in Republican-Period Shanghai: From Pictorialism to Modernism,” in Bridges to Heaven: Essays on East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong, edited by Dora C. Ching and Jerome Silbergeld (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 849–74. Most recent is the welcome addition of Claire Roberts’s Photography and China (London: Reaktion Books, 2013), which appeared after I had submitted this essay; see especially ch. 3, “China Modern,” 65–90. Chen Hsueh Sheng’s “Art Photography in China before 1949: The Continuation and Transformation of an Elite Culture” (PhD dissertation, University of Melbourne, 2010) also reached me as I made final revisions; I thank H. Tiffany Lee for bringing it to my attention.

Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak have recently argued that already by the 1880s, if not well before, there were photographers such as Liang Shitai (or See Tay, active 1870s–80s) who produced images that not only answered the needs of a client but also possessed an aesthetic dimension; see “Through a Foreign Glass: The Art and Science of Photography in Late Qing China,” in Brush and Shutter: Early Photography in China, edited by Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak (Los Angeles: the Getty Research Institute, 2011), 34.

Accomplished Chinese photographers during the late Qing period certainly looked to aspects of traditional Chinese painting to aid them in composing commercially effective portraits and landscapes. In addition, the skilled productions by such professional photographers as Lai Afong (active 1859?–1900) in Hong Kong and Liang Shitai in Tianjin arguably laid the foundation for the art photography of the Republican period. Nevertheless, the later art photographers seem to have possessed little, if any, awareness of the work of these predecessors; thus far I have found no comments by photographers of the 1920s and ’30s that offer evidence of their having looked to earlier Chinese photographers, those identified by current historians as holding the utmost importance in what now is being defined as the canon of Chinese photography. For consideration of Lai Afong and his photography in relation to that of John Thompson (1837–1921) and other Western photographers working in China, see Roberta Wue, “Picturing Hong Kong: Photography through Practice and Function,” in Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855–1910, edited by Roberta Wue (New York: Asia Society Galleries and George Braziller, 1997), esp. 37–39; and Sarah Fraser, “Chinese as Subject: Photographic Genres in the Nineteenth Century,” in Brush and Shutter, esp. 94–99.

The use of terms such as meishu sheying and yishu sheying grows out of a larger transnational and, as Aida Wong puts it, “epochal” shift in the way Chinese intellectuals at the beginning of the Republican period appropriated Japanese linguistic formulations to develop an aesthetic discourse, paralleling that which existed in the West, for the fine arts―whether painting, sculpture, architecture, or photography; see Aida Yuen Wong, Parting the Mists: Discovering Japan and the Rise of National-Style Painting in Modern China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press and the Association for Asian Studies, 2006), 35–36.

Chen Shen and Xu Xijing note the 1918 exhibition of photography at the Tianjin Museum, which may have been one of the first exhibitions of artistic photography. They surmise that not all the photographs could have been produced by photographers working for commercial studios; see Zhongguo sheying yishu shi, 79.

Leo Ou-fan Lee, “In Search of Modernity: Some Reflections on a New Mode of Consciousness in Twentieth-Century Chinese History and Literature,” in Ideas Across Cultures: Essays on Chinese Thought in Honor of Benjamin I. Schwartz, edited by Paul A. Cohen and Merle Goldman ( Cambridge and London: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1990), 110–11.

For an overview of the period and the demise of the Qing dynasty, see Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China (New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1990), especially chs. 10 and 11. For the inadequacy of the “binary” model of China versus the West in mapping the formation of Chinese modernism, see Shu-mei Shih, The Lure of the Modern: Writing Modernism in Semicolonial China, 1917–1937 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 4–5 and 140–44.

Charlotte Furth, “Intellectual Change: From the Reform Movement to the May Fourth Movement, 1895–1920,” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 12, Republican China 1912–1949, part 1, edited by John K. Fairbanks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 353. For a more recent consideration of Liang’s evolving conception of nationalism as it relates to his ideas about “new” learning and “modern historical consciousness,” see Xiaobing Tang, Global Space and the Nationalist Discourse of Modernity: The Historical Thinking of Liang Qichao (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 13–29. Joseph R. Levenson’s groundbreaking study of Liang’s changing assessment of how best to reconcile Chinese ideals with Western modernism, Liang Ch’i-ch’ao and the Mind of Modern China, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959), remains relevant.

Leo Ou-fan Lee, “Literary Trends I: The Quest for Modernity, 1895–1927,” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 12, Republican China 1912–1949, part 1, 455.

Mayching Kao, “Reforms in Education and the Beginning of the Western-Style Painting Movement in China,” revised version reprinted in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998), 153–54. See also the comments about Cai Yuanpei’s ideas and advocacy of art education in Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, The Art of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 31.

Benjamin I. Schwartz, “Themes in Intellectual History: May Fourth and After,” in the Cambridge History of China, vol. 12,), 407. Shu-mei Shih has written of the parallels “between the Meiji and May Fourth enlightenment projects”; see The Lure of the Modern, 142–43.

For overviews of the vernacular language movement, see Tse-tsung Chow, The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1960), 271–79, and Vera Schwarcz, The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 56 and 207–208.

The photograph I attribute here to Fang Wenhuai may have been made by one of his brothers, Fang Wenyang 方文揚 or Fang Wenyuan 方文源. It appears in an album of images by all three. More research is needed to determine which photographs are by whom. Fang Wenhuai, and possibly his brothers, participated in the Fudan University Photographic Society, which held at least one public exhibition in Shanghai; see Wenhua 文華, no. 6 (January 1930), 18. Chen Rentao’s photograph appeared in Zhonghua sheying zazhi 中華摄影雜誌 (The Chinese Journal of Photography), no. 7 (July 1933), 296.

Xu Ruiyue 徐瑞岳, Liu Bannong nianpu 刘半农年諩 [Liu Bannong: A Chronological Biography] (Nanjing?: Zhongguo kuangye daxue chubanshe, 1989), 13. See also Xu Ruiyue, Liu Bannong pingzhuan 刘半农评传 [Liu Bannong: A Critical Biography] (Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe, 1990), 18; and ZGSYS, 178.

Liu Bannong, Bannong tanying [Bannong’s Comments on Photography] (Shanghai: Kaiming shudian, 1934), 4th ed., 11–13. Translations of this and subsequent texts from primary sources are the author’s.

Yu-Kung Kao, “Chinese Lyric Aesthetics,” in Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting, edited by Wen C. Fong and Alfreda Murck (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991), 87.

Wen C. Fong, Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, 8th–14th Century (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), 431.

For informal painting in the xieyi mode during the Ming dynasty and its increasing commodification by the Qing period, see James Cahill, The Painter’s Practice: How Artists Lived and Worked in Traditional China (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 16–22.

Little is known about Wang Mengshu. For Chen Wanli’s biography, see ZGSYS, 177–78, SHSYS, 23–24, and its more extensive consideration in Chen and Xu, Zhongguo sheying yishu shi, 92–96.

For an account of Ni’s life and art, see James Cahill, Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yuan Dynasty, 1279–1368 (New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1976), 114–120; and Maxwell K. Hearn, “The Artist as Hero,” in Wen C. Fong and James C. Y. Watt, Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996), 311–19.

In later centuries, Ni Zan’s style exerted a significant influence on painters associated with the Anhui school of painting; see James Cahill, “Introduction,” and Julia Andrews and Haruki Yoshida, “Theoretical Foundations of the Anhui School,” in Shadows of Mt. Huang: Chinese Painting and Printing of the Anhui School, edited by James Cahill (Berkeley: University Art Museum, 1981).

The painting Remote Stream and Cold Pines, c. early 1370s, in the Beijing Palace Museum, exemplifies Ni’s reduction to only a few elements of his already spare landscape mode. In this painting, even the empty pavilion has been eliminated.

For an entry about Zheng Min by Haruki Yoshida and a reproduction of an album leaf (present collection unknown but formerly on loan to the Princeton University Art Museum) that shows an extremely minimal rendering of the Ni Zan mode, see Shadows of Mt. Huang, 123 and 124, fig. 58c.

Many writers about pictorialism note this characteristic. See Kristina Lowis, “European Pictorial Aesthetics,” in Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888–1918, edited by Phillip Prodger (St. Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 2006), 49.

See the author’s “Flying Eagle (Feiying): Jin Shisheng and the Cause of Photography in 1930s China” (飞鹰:金石声和三十年代的中国摄影事业), in Chenji: Jin Shisheng yu xiandai zhongguo sheying 陈迹: 金石声与现代中国摄影 [Relics: Jin Shisheng and Modern Chinese Photography], edited by Jin Hua (Shanghai: Tongji University Press, forthcoming); in this volume see also Wu Hung, “Photography about Photography: Jin Shisheng and His Interior Space” (关于摄影的摄影: 金石声和他的内部空间). As for foreign photographic publications available in Beijing, Liu Bannong mentions American, British, and Japanese “annuals” in his preface to the Light Society’s second annual; see the passage that I quote.

The majority of those published that are known to the author appeared in the two annuals published by the Beijing Light Society, for which Liu Bannong added prefaces, in 1928 and 1929. The first contained five photographs by Liu and the second, seven.

A particularly evocative example from the nineteenth century, though impossible to date precisely, is a leaf from an album (c. 1860s–70s) of sixty landscape views produced by the little-known Fuzhou studio Tung Hing (in present-day Mandarin: Tongxing 同興) and now in the Getty Research Institute. According to its caption, the photograph pictures Mt. Doumao in the background. In the middle distance, a blurred ribbon of river winds with a single, motionless boat moored along the shore closest to where the photographer stood; see Brush and Shutter, plate 42, 165. The photograph, an albumen print, was produced from a glass-plate negative. It typifies a kind of landscape view that, using this process, with its inherent limitations (e.g., the motion of the river’s current could not be caught clearly, nor could the atmosphere of the sky), offered abundant visual information. Such views were produced around the globe—from the American western geological survey photography to the British colonialist photography in India. The clarity of this rendering of a boat on the water, however, differs stylistically from how the later pictorialist photographers, who favored less detail and a more atmospheric effect, tended to handle the subject. I thank the anonymous reader of this article for bringing this photograph to my attention. For an example of the subject, vignetted to enhance its picturesque quality, by the British photographer William Saunders (1832–1892) from c. 1870, see Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China: Western Photographers 1861–1879 (London, Bernard Quaritch Ltd, 2010), 333; see the discussion of Saunders’s importance in this volume, 83–108.

See Qiu Ying zuopinzhan tulu 仇英作品展圖録 [Illustrated Catalogue to an Exhibition of the Paintings by Qiu Ying] (Taibei: Guoli gugong bowuyuan, 1989; rpt, 1995), 43–54.

Photographs by Peter Henry Emerson (1856–1936) and Frank Sutcliffe (1853–1941) exemplify both the interest in the theme and the recognition of its pictorial potential. For examples by other European photographers, see the pictures by Paul de Singly (Port of Dieppe, France, after 1904), Heinrich Wilhelm Müller (Fishing Boat, Blankenese, Germany [Blakeneser Fisherewer], 1898), and Gustave Marissiaux (Night in Venice, 1905), reproduced in Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888–1918, English edition edited by Phillip Prodger (London and New York: Merrell Publishers, 2006), 38, 120, and 165.

Liu Bannong, “Xu” (preface), Beijing Guangshe nianjian 北京光社年鑑 [The Beijing Light Society Annual] (Beijing: Beijing guangshe, 1929), 4–5.

For an overview of the development of fine-art photography in Japan and the response of Japanese photographers to Western pictorialism, see Kaneko Ryūichi, “The Origins and Development of Japanese Art Photography,” in Anne Wilkes Tucker, et al., The History of Japanese Photography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in Association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003), 100–13; and Karen M. Fraser, Photography and Japan (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 14–21 and 55–62. The role early Japanese art photography undoubtedly played in the development of China’s fine-art-photography movement requires study. For example, one would like to know which early Japanese photographic publications were in circulation in China. One also wonders to what extent Chinese amateur photographers in Shanghai, especially after hostilities with Japan had begun in 1932, deliberately avoided any mention of Japanese photographic precedent they had encountered. For a similar silence with regard to Japanese study of traditional Chinese painting and its impact on early-twentieth-century practitioners of guohua 國畫 (or “national-style painting”), see Aida Yuen Wong, Parting the Mists, xxiv and ch. 1.

Wong’s Parting the Mists offers a detailed and illuminating discussion of this period’s Sino-Japanese exchange with regard to both the practice of painting and the writing of histories about it. Of course, such cross-pollination had been occurring in the latter half of the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the career of Ren Bonian (1840–1896) 任伯年 and discussed pointedly in Yu-chih Lai, “Remapping Borders: Ren Bonian’s Frontier Paintings and Urban Life in 1880s Shanghai,” in the Art Bulletin, vol. 86, no. 3 (September 2004), esp. 566.

For a brief biography of Trinks, who was born in Brazil but was schooled in Germany, see Impressionist Camera, 310.

I use the term “appropriation” in its benign sense and with implicit reference to the many forms it may take in the arts; see James O. Young, Cultural Appropriation and the Arts (Malden, MA, and Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), esp. 1–9 and 157–58.

Lee, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945 (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 1999), 42 and 45–46.

See ZGSYS, 265–70. Zhonghua sheying zazhi was launched by Hu Boxiang in October 1931 and continued for eleven issues, until June 1936. Chenfeng appeared in December 1933 and concluded with its twelfth issue, in October 1935. Feiying was published by the Shanghai Guanlong Photographic Materials Company; its first issue appeared in January 1936 and its last in July 1937 (no. 19).

To identify Lang Jingshan as an “amateur” art photographer is not quite accurate. Although well educated and trained in traditional Chinese painting, in his mid-twenties Lang began working for Shanghai’s Shibao (Illustrated Times) as a news photographer. Chen and Xu state that he was China’s first photojournalist. A few years later, Lang opened a studio that specialized in portrait and advertising photography; see Zhongguo sheying yishu shi, 140.

For a more in-depth consideration of Feiying and the editors’ ambitious response to European photographic publications, see the author’s forthcoming “Flying Eagle (Feiying): Jin Shisheng and the Cause of Photography in 1930s China” (飞鹰:金石声和三十年代的中国摄影事业), in Chenji: Jin Shisheng yu xiandai zhongguo sheying 陈迹: 金石声与现代中国摄影 (Relics: Jin Shisheng and Modern Chinese Photography).

See the author’s “Fine Art Amateur Photography in Republican-Period Shanghai: From Pictorialism to Modernism,” 866–72.

The Grand Cinema was designed in 1933 by the Czech architect Ladislaus Hudec; see Lee, Shanghai Modern, 84. For elements of Art Deco design that span architecture to the graphic arts, see Ellen Johnston Laing, “Art Deco and Modernist Art in Chinese Calendar Posters,” in Visual Culture in Shanghai, 1850s–1930s, edited by Jason C. Kuo (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2007), 241–78. Entitled Lines 缐, a photograph of the theater by Ao Enhong 敖恩洪 (1909–1990) takes a similarly modernist approach; see Heibai yingji [Black & White Pictorialist], vol. 1 (Shanghai: Heibai sheying she, 1934).

Lang’s Spring Trees and Majestic Peaks seems to recall especially Fan Kuan’s 范寛 Travellers among Streams and Mountains (c. 1000) in its compositional emphasis on a strongly defined shape in the foreground that is juxtaposed, across a spatial divide, with the rugged peaks in the middle distance. Fan Kuan’s painting at the time was part of the imperial collection. When Lang produced this photograph, however, using what appear to be two different negatives, was Fan Kuan’s now iconically famous work knowable to students of Chinese painting or photography? Further research is required to determine what paintings were published as illustrations in the early surveys of Chinese art that were beginning to appear during the Republican period; for a discussion of surveys such as Pan Tianshou’s 潘天授 (1897–1971) Zhongguo huihua shi 中國繪畫史 [History of Chinese Painting], published in 1926, see Wong, Parting at the Mists, ch. 2 and esp. 41–48. For a discussion of Lang Jingshan’s photography and its evocation of themes, moods, and compositional structures found in painting, see Ch’en Pao-chen 陳葆真, “Wenrenhua de yanshen―Lang Jingshan de sheying yishu” 文人畫的延伸―郎静山的摄影藝術 (The Extension of Literati Painting―Lang Jingshan’s Photographic Art), in Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宫文物月刊 (The National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art), vol. 20, no. 10 (2003), 42–57.

For an account of Hu Boxiang’s career as a commercial artist at BAT and correspondences between his painting and photography, see Laing, Selling Happiness (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004), 176–86.

Hu’s Threshing Wheat has many similarities with Emerson’s During the Reed-Harvest, plate XXVIII in Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads (1886). This picture was one of the plates Emerson acknowledged as a product of his “ideal partnership” with the painter and his traveling companion, T. F. Goodall; see John Taylor, “Emerson and Tourism in East Anglia,” in The Old Order and the New: P. H. Emerson and Photography, 1885–1895 (Munich, Berlin, London, and New York: Prestel, 2006), 15, n. 7; for an astute consideration of Emerson and pictorialism, see Taylor’s comments in the same volume, 56–57.

It is an odd coincidence that when Hu Boxiang made Threshing Wheat, Emerson, although very old and having ceased photographing decades earlier, was still alive.

Nie Guangdi 聶光地, “Xu” (preface), Heibai yingji 黑白影集 [The Black and White Pictorialist], vol. 3 (1937), 4. For a translation of these specific remarks, see the author’s “Fine Art Amateur Photography in Republican-Period Shanghai,” 869.

The new and modern reality in Shanghai was certainly much like that in Western cities as described by Christopher Phillips: “The camera did not simply mirror the existing state of cities like New York, Paris, Berlin, or Moscow, which in reality were often still weighed down by the social and architectural legacies of the past; instead, it selectively highlighted the most dramatic elements of the emerging urban order”; see his “The Photographer in the City,” in Modernist Photography: Selections from the Daniel Cowin Collection, edited by Christopher Phillips and Vanessa Rocco (New York and Göttingen: International Center of Photography and Steidl, 2005), 11.

Luo Gusun’s photograph appeared in Heibai yingji [The Black and White Pictorialist], vol. 2 (June 1935), no. 66; Shang Wu’s in Chenfeng [Dawn Wind], no. 8 (September 1934).

For a concise narrative of Japan’s consolidation of power in China’s northeast from 1928 to 1933, a source for enormous urgency, see Spence, The Search for Modern China, 390–96.

For the most extensive, though brief, biographical comment about Mennie available to date, see Clark Worswick, “Photography in Imperial China,” in Imperial China: Photographs 1850–1912 (New York?: Penwick Publishing, 1978), 146. Mennie seems neither to have exhibited photographs nor to have participated in any photographic societies. He also seems to have had no contact with any of the prominent Shanghai amateur photographers.

Mennie, through A.S. Watson, published a series of books, some with a precise publication date and some without, throughout the 1920s. The most sumptuous of these is The Pageant of Peking (1920, with a second edition in 1921 and a third in 1922). Among other books are China, North and South (1920?); China by Land & Water (1920?); Glimpses of China: A Series of Vandyck Photogravures Illustrating Chinese Life and Surroundings (1920s?); and The Grandeur of the Gorges (1926). His photographs also illustrated Gretchen Mae Fitkin’s The Great River: The Story of a Voyage on the Yangtze Kiang (Shanghai: North China Daily News & Herald, 1922) and Elizabeth Cooper’s My Lady of the Chinese Courtyard (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1914). For information contained in this note, I am grateful to an e-mail communication (November 29, 2006) from Ms. Gillian Currie, of the National Gallery of Australia.

“Point Rash Judgment,” in Lyrical Ballads is also known by its first line “A Narrow Girdle of Rough Stones and Crags.” For a discussion of the poem and its contrite narration of an encounter between the poet and a debilitated “Peasant,” see Ron Broglio, Technologies of the Picturesque: British Art, Poetry, and Instruments, 1750–1830 (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2008), 111–16.

Mennie’s photograph, and the two others I include in this essay, appears in the above-noted Glimpses of China. Peng Wangshi’s appears in the first issue of Tianpeng 天鵬 (The China Focus), vol. III, no. 1 (July 1, 1928), after the magazine had begun to focus solely on art photography and adopted a title in English to indicate that. It is probable that the two photographs were made within five to ten years of each other.