Piety and Power: The Theatrical Images of Empress Dowager Cixi

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Fig. 1: Xunling, 'Empress Dowager Cixi and attendants on a barge on Zhonghai Lake, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 243. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 1: Xunling, 'Empress Dowager Cixi and attendants on a barge on Zhonghai Lake, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 243. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.From the 1860s until her death in 1908, the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908) was the dominant political figure in the court of the Qing dynasty(1644 to 1911). In spite of having begun her career at court as a mid-level concubine, her keen political acumen gave her Imperial authority nearly to the end of the Qing dynasty. During the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Cixi was accused of personally encouraging the killing of foreigners and Chinese Christians, and blamed for the ensuing invasion and occupation by Western nations. In response, the Qing court initiated measures to reach out to foreign nations through personal diplomacy. Members of the diplomatic community in Beijing were invited into the palace for receptions, audiences and luncheons with Cixi, and Manchus with extensive experience overseas were appointed to assist Cixi with the confusing social contacts with Westerners. One of these foreign-raised Manchus was a young man named Xunling (c.1880–1943), the son of the former ambassador to Tokyo and Paris. Upon learning that Xunling had picked up photography while overseas, Cixi engaged him to take a series of individual portraits and elaborate group tableaux. The series, taken in 1903 and 1904, provides one of the most intimate visual representations of the inner Qing court.

The Archives of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler gallery contains 36 of Xunling’s original glass-plate negatives. What the original purpose of the photographs was is difficult to assess. Prints were hung in the palace, distributed to ministers and associates, and presented to diplomatic visitors and foreign heads of state. The six images below were chosen as an illustration of Cixi’s primary imperative to communicate her authority and solidarity with other members of the court.

By all accounts, Cixi was fascinated with the photographic process, and took an active role in directing the content and composition of each image. Certainly, the photographs reflect her personal aesthetic preferences for rich, lushly detailed display. Additionally, a close analysis of the photographs reveals a wealth of visual and textual markers that denote her religious, political, and theatrical interests and alliances.

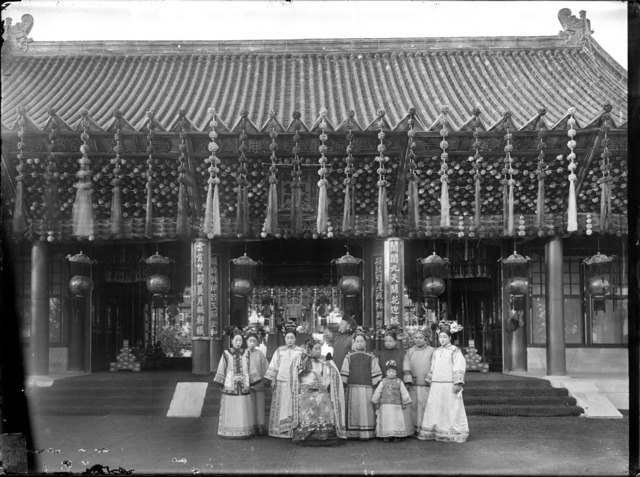

Perhaps the most enduring yet enigmatic of Cixi’s photographic portraits is the coquettish standing pose as she gazes into a mirror while placing a flower in her hair (Fig. 2). Standard interpretation suggests that she is somehow reliving her youth, when her beauty caught the eye of an emperor. A more convincing interpretation, however may be found in her enduring love of theater. In an early scene in the Ming dynasty play The Peony Pavilion (牡丹亭)the heroine Du Liniang gazes into a mirror as her attendant places a flower in her hair before descending to the garden where she receives a vision of her future lover. Images and sequences of the scene from the Kunqu (traditional opera) version of Peony Pavilion [1] are strikingly similar in pose. Theater performances were an intrinsic part of court ritual, and a pose from this favorite drama would have been readily recognizable to other members of the Qing court, along with its literary theme of longevity and permanence. In Fig. 3, Cixi is surrounded by an extensive retinue in front of Paiyunmen (排云门), the main gate of Wanshoushan (万寿山) of the Summer Palace. As in the single portrait, Cixi adopts the same pose, underscoring the importance of conveying wishes for the longevity of the Qing dynasty.

Fig. 2: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 251. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 2: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 251. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Fig. 3: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi with attendants in front of Paiyunmen, Summer Palace, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 260. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 3: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi with attendants in front of Paiyunmen, Summer Palace, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 260. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.At the farther end of the performative tableaux are the elaborately composed portraits of Cixi in the guise of Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva who embodies compassion and mercy (Figs. 4 and 5). Given that all the studio photographs had the same backdrop illustrating the Purple Bamboo Grove of Avalokitesvara, it is conceivable that these compositions were the first priority of the photography project. According to her attendant and biographer (and sister to the photographer) Der Ling, Cixi is quoted as saying:

“Whenever I have been angry, or worried over anything, by dressing up as the Goddess of Mercy it helps me to calm myself, and so play the part I represent. I can assure you that it does help me a great deal, as it makes me remember that I am looked upon as being all-merciful. By having a photograph taken of myself dressed in this costume, I shall be able to see myself as I ought to be at all times.”[2]

Fig. 4: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi in the guise of Avalokitesvara'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 245. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 4: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi in the guise of Avalokitesvara'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 245. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Fig. 5: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi in the guise of Avalokitesvara'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 246. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 5: Xunling, 'The Empress Dowager Cixi in the guise of Avalokitesvara'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 246. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.Certainly there were many imperial precedents for portraits identifying with a divinity, such as the 18th-century paintings of the Qianlong Emperor (1711–99) as Manjusri. (link: http://asia.si.edu/collections/singleObject.cfm?ObjectNumber=F2000.4)

Rather than a narcissistic expression of personal aggrandizement, such portraits were intended to display imperial piety and spiritual aspiration. Cixi's role-playing as Avalokitesvara conveys a similar devotion to a more popular, gender ambiguous deity as a means of integrating temporal and spiritual authority—a challenge all the more urgent given her status as a female head of state.

Finally, more overt theatrical subjects emerge in a series of images taken at Zhonghai (中海), one of the lakes directly west of the Forbidden City (Figs. 1 and 6). According to the archives of the Imperial Household Department, in 1903 the Empress Dowager issued a directive to the Imperial Household Department for the photo shoot:

For the 16th day of the 7th month photo shoot on Zhonghai, prepare a boat that has no sail or roofing. Fourth daughter of Yikuang shall dress up as Sudhana in a Lotus costume and a Wu- Beng. Li Lianying shall dress up as Skanda, perhaps with Skanda’s Helmet and related paraphernalia. Deling and Rongling shall play Punt Fairies. They shall have the fisherman’s bonnets and wear the costume dresses of Bai Suzhen, who is a white snake that has taken on human form. Perhaps they should also have some paraphernalia—either red or green would work. Have the Garden Department prepare two paddles for the junk, and have San Shun who works at the Imperial Household Department prepare several bamboo rods with leaves. All items must be ready for my inspection on the 8th day of the 7th month.[3]

Fig. 6: Xunling, 'Empress Dowager Cixi and attendants on a barge on Zhonghai Lake, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 265. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.

Fig. 6: Xunling, 'Empress Dowager Cixi and attendants on a barge on Zhonghai Lake, Beijing'. China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904. Glass plate negative, SC-GR 265. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives.The overall composition is a reference to the a scene from Legend of White Snake (白蛇传), a favorite popular favorite drama. Yet in addition to the costumes and props relating to the play, Cixi adds a disparate array of textual and visual elements.

On the screen behind her is a banner again proclaiming her as a manifestation of Avalokitesvara. Attached to three-legged archaic bronze vessel before her is a slip of paper with Ningshougong (宁寿宫), the palace complex built within the Forbidden City for the retirement of the Qianlong Emperor. And rising from the bronze before her is a stylized longevity character, on top of which are three characters Guangrenzi (广仁子), the Empress Dowager’s Daoist title.

The teeming assemblage of theatrical tableaux, political references, and religious titles establishes the scene as more than an outing with eunuchs and attendants in opera costumes; on the contrary, the camera served to create a calculated schematic of intersecting references to her own religious and political legitimacy within the factional environment of the final years of dynastic decline.

David Hogge is the head of the Archives of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. He is the curator of the upcoming exhibition: “Power|Play: China’s Empress Dowager”, which will be at the Sackler Gallery in Washington DC from September 24, 2011 to January 29, 2012.

Notes

Cixi was an enthusiastic supporter of theater arts, supporting both Kunqu, the traditional Chinese opera, as well as the younger form of Jingqu, or Beijing opera.

Derling, Princess. Two Years in the Forbidden City (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1911)

Translated from Wei Jiangong et al, eds. “Qingdai Baozuo” in Suoji Qinggong (Beijing: 1990)