4.4. Translation

In light of the foregoing, we can now make sense of Latour's thesis, cited in the epigraph to this chapter, that objects “interpret” one another. Insofar as all objects are operationally closed, no object can transfer a force to another object without that force being transformed in some way or another. This generates a specific set of questions when analyzing relations among entities in the world. On the one hand, in any discussion of relations among entities, we must first determine whether the receiving entity even has channels capable of receiving perturbations from the acting entity. Because substances only maintain selective relations to their environment, they are not open to all perturbations that exist in their environment. As we saw in the last section, for example, rocks, as far as we know, are indifferent to our speech. This sort of selectivity is true not only of relations of objects between different sorts, but also of relations between objects of the same sort. Many, I'm sure, have experienced and been baffled by conversations with others from very different theoretical backgrounds and orientations. In such discussions, points and claims you take for granted as obvious seem not even to be registered or noticed by the interlocutor when made. Here we have different forms of selective openness among humans in discourse.

On the other hand, in those cases where an entity is open to perturbations of a particular sort, we must nonetheless be attentive to the manner in which the entity that receives that perturbation transforms it according to its own organization. In other words, we cannot begin with the premise that the effect is already contained in the cause, but must instead be attentive to how the cause is transformed into something new and unexpected. In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan contrasts laws and causality in a way that resonates nicely with this point. [202] As Lacan remarks,

Lacan goes on to remark that,

Lacan concludes “there remains essentially in the function of the cause a certain gap”. [205] In characterizing causality in terms of a gap and something that “doesn't work”, Lacan emphasizes the manner in which the effect of a cause always contains an element of surprise or something that can't simply be deduced from the cause. Here there's a way in which the effect is always in excess of the cause. And the claim that the effect contains something in excess of the cause is the claim that the entity being affected translates the cause producing something new.

Lacan's concept of causality is deeply related to his understanding of objet a, the object-cause of desire, and the unconscious. Without going into all the details of Lacan's understanding of the unconscious, objet a, and desire, we can here make a few brief remarks as to how this is to be understood. The first point to note is that objet a is not the object desired, but the object that causes desire. In other words, the object desired can be quite different from the object-cause of desire or the objet a. The objet a is rather that gap that generates desire. Desire is the effect of objet a, and objet a is the cause of desire. Put otherwise, we can say that it is that point where the symbolic fails and that it is the explanation of the effects of this failure. To illustrate this point, take the example of someone who desires an expensive luxury car. The car is the object of desire, but not the object-cause of desire. Rather, the object-cause of the desire for the car is perhaps the gaze of others who will envy the car or attribute status to the owner of the car.

This relation can be illustrated in terms of Lacan's discourse of the master, first introduced in Seminar XVII:

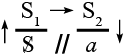

Each of Lacan's four discourses has four positions and defines a structure. [206] In the upper left position we have an agent, addressing an other in the upper right position, producing a product in the lower right position, with an unconscious truth in the lower left position.

One way of reading Lacan's discourse of the master is in terms of how signifiers relate to one another. We have a master-signifier, S1, relating to another signifier, S2, producing a remainder, a. The point is that in all speech or utterances something escapes. When we utter something, we feel as if we never quite articulate what we wish to say. Indeed, we aren't even entirely sure what we wish to say in our own speech. On the other hand, when we hear another person's utterances, we're never quite sure why they say what they say. This is the gap that lies at the heart of all discourse. One way of thinking about Lacan's discourses is as diagrams of little machines in interpersonal relations. In the diagram above, it is paradoxically the product, the failure, objet a, that keeps the discourse going. Because I never quite feel that I've articulated what I wish to say and because I'm never quite sure if I've understood what the other has said, new utterances are produced that strive to capture this allusive remainder that perpetually recedes in the discourse.

Within a psychoanalytic context, the gap by which objet a functions as the object-cause of desire can be fruitfully thought in terms of the role played by the unmarked side of a distinction as it functions in psychic systems. Put a bit differently, while the unmarked side of a distinction is not indicated by a system employing a particular distinction, this unmarked side nonetheless has effects on how the psychic system functions. In his discussion of the cause, Lacan remarks that “what the unconscious does is show us the gap through which neurosis recreates a harmony with a real”. [207] Here the unconscious is the network of unconscious signifiers, while the gap is the real. The psychoanalytic formation (the symptom) is the harmony recreated with the real.

To illustrate this point, I refer to an example from early in my own analysis years ago. During this time, I was just beginning to teach. This was back in the days when chalk was still used. Much to my dismay, I found that I was breaking multiple pieces of chalk during every class session. Indeed, this symptom was so pronounced and noticeable, that it became a running joke with my students. They even got together and left a chalk guard in my mailbox with a petition written in calligraphy imploring me to stop killing the citizens of “Chalkville” and a picture of a piece of chalk dressed in armor. Now, I found all of this quite upsetting as I felt it was undermining my authority in the classroom and revealing my incompetence. One day, in a session, I was rambling on about this little symptom. “I don't know what my problem is. I can't seem to modulate my pressure on the chalk. I try not to, but I always end up pressing too hard. Why can't I use less pressure?” And so on. As my ramble went on, my analyst, in a flat voice, intoned in a statement that was ambiguous as to whether it was a question or a statement, “pressure at the board?” “Yes”, I responded, completely missing the polysemy of his remark, “pressure at the board! I just can't keep myself from using too much pressure!” After this session, I didn't think about the discussion of the chalk at all. Two weeks later, however, I noticed that I hadn't broken any chalk for two weeks. Somehow the desire embodied in my symptom had been articulated and therefore, from the standpoint of my unconscious, I no longer had to break chalk to articulate that desire.

Now where is the objet a, desire, and the unconscious in this example? Where is the gap through which the unconscious recreates a harmony with the real? Here the objet a is very likely the gaze of my students. That gaze poses a question: what am I for them? This gaze, however, was not the object of my desire, but the cause of my desire. It was that which set the desire in motion. In his various glosses on desire, Lacan said that “desire is the desire of the Other”. This is a polysemous aphorism that has a number of different connotations. It can mean that desire desires the Other. Likewise, it can mean that our desire is not, as it were, truly our own, but rather is the Other's desire. That is, it can mean that we desire as the Other desires, as in the case of an adult who lives her life pursuing the career her parents wanted. Finally, it can mean that we desire to be desired by the Other. In this instance, my chalk breaking symptom did not seem to desire the Other (my student's here standing in the place of the Other), but rather seemed to be an articulation of their desire (or, rather, my fantasy of what they desired). Faced with the opacity or enigma of my students' desire, my unconscious sought to transform this traumatic and enigmatic desire into a specific demand or judgment: “You are not competent, you do not belong here!” In other words, through the breaking of the chalk I was perhaps unconsciously trying to satisfy my fantasy of what I took to be their demand. The breaking of the chalk at the board was both an articulation of how I was feeling (“pressured at the board”) and a potential solution to the pressure I was experiencing: “if I'm incompetent then I won't have to teach!” The unconscious recreated a harmony with the real by giving content to the enigmatic gaze of my students through the symptom of breaking the chalk.

The gap functions in a very specific way in Lacan's conception of the mechanisms of the unconscious, but we can say that Lacan also makes a broader and more profound point about the gap and the relationship between cause and effect that holds for all inter-object relations. Here we can coin the aphorism, “there is no transportation without translation”, or, alternatively, “there is no transportation without transformation”. Here we must take care not to take Lacan's notion of the gaze too literally, but the point in this connection would be that the effects of the gaze as a perturbation cannot be anticipated in advance. Rather the effect that the gaze produces is an aleatory product of the organization or virtual proper being of the system that is perturbed by the gaze. Each substance translates perturbations in its own particular way.

Here, then, we can make sense of what Latour means when he claims that objects interpret one another. To interpret is to translate, and to translate is to produce something new. As Latour remarks, “[t]o interpret something is to say it in other words. In other words, it is to translate”. [208] The translated is never identical to the original, but rather produces something different from the original. For example, if this book is some day translated into, say, German, it will very likely take on resonances that it doesn't have in English. My discussions of “existence” might be translated into Dasein. Yet the German term Dasein has connotations that English doesn't have, such as “there-being” or “here-being”. In being translated into another language a text becomes something different. Likewise, when a perturbation is received by another entity, it becomes something different. As Latour says earlier in Irreductions, “[n]othing is, by itself, the same as or different from anything else. That is, there are no equivalents, only translations”. [209] The point here is that no perturbation ever retains its identity or self-sameness when transported from one entity to another, but rather becomes something different as a consequence of being translated into information and then producing a particular local manifestation in the receiving object.

Along these lines, Latour elsewhere draws a distinction between mediators and intermediaries in Reassembling the Social. As Latour articulates this distinction,

All objects are mediators with respect to one another, transforming or translating what they receive and thereby producing something new as a result. By contrast, intermediaries merely carry a force or meaning without transforming it in any way. In this connection, we can say that the concept of intermediaries treats objects as mere vehicles of the differences contributed by another entity. In one of his most recent works, Latour drives this point home, remarking that,

Our treatment of objects in terms of autopoietic and allopoietic machines has explained just why this is the case. Insofar as all entities draw a system/environment distinction and transform perturbations into information as a function of their own internal organization, they always contribute something new to the perturbations they receive.

The concept of translation, coupled with the distinction between mediators and intermediaries has profound implications for both theory and practice. In the docile bodies chapter of Discipline and Punish, we encounter a prime example of theories and practices organized around the conceptualization of substances in terms of mere intermediaries. [212] There Foucault analyzes a disciplinary structure of power that aims to form the soldier down to the tiniest detail.

This conception of the formation of the soldier is premised on an implausible idea of causation where causes are transported from one object to another without remainder. Here the soldier is a pliable clay that can be formed however we like. Here information is conceived as something that is transported as self-identical, producing a univocal effect in the body of the soldier-to-be. What is entirely missed in such a model is the manner in which the entity receiving the perturbation transforms it according to its own organization.

In a very different context, biologist Richard Lewontin contrasts the difference between how applied biologists approach research into plants and animals and how developmental biologists in the laboratory approach plants and animals. [214] For the developmental biologist in the laboratory, a lot of research revolves around the manipulation of genes to see how they affect the phenotype. This encourages a conception of organisms in which genes are thought of as already containing the information whereby the phenotype is produced. In other words, genes are thought as a map or blueprint of the organism. By contrast, applied biologists investigating potentially new crops, test these crops for several years by growing variants of the crop in different environments or in different regions. As Lewontin notes, the crop that is eventually chosen for sale is not necessarily the crop that produces the largest yield but the one that produces the most consistent yield when grown in a variety of different regions. [215]

In Lewontin's example, we find a perfect instance of the difference between approaching the world in terms of intermediaries and approaching the world in terms of mediators. In treating information as already contained in the genes, the developmental biologist treats the organism as a mere intermediary. The blueprint is already contained within the genes and it is enough to merely manipulate the genes in a particular way to produce a particular phenotype. The point here is not that such manipulations don't produce particular phenotypes but that 1) these particular perturbations are a particular environment, and 2) in many instances environmental perturbations can produce similar transformations of phenotypes. As a consequence, we should see genes not as something that already contain information, but rather as one causal factor among others, where information is not already there, but rather where it is produced as a result of operations in the system/environment relation. In this connection, Susan Oyama calls for parity in investigating objects. As Oyama puts it, developmental systems theory (DST),

In contrast to the developmental biologist described by Lewontin, the applied biologist's investigative practice implicitly indicates parity reasoning in its approach to new crops. In growing crops in different environments and regions, the applied biologist works on the premise that genes are not blueprints already containing information, but rather are one causal factor among others that can generate very different effects at the level of the phenotype when grown under different environmental conditions.

For the applied biologist, the entity (the seeds) are full-blown mediators. Between cause and effect there is here a gap, such that the effect is unknown. That is, we don't know what phenotypes will be produced under these circumstances. By contrast, the gap between cause and effect tends to disappear in the research practices of Lewontin's developmental biologist. Lewontin's developmental biologist, of course, begins with the premise that we don't know what phenotype will be produced if we manipulate this gene. The point, however, is that through the focus on genes alone, the developmental biologist tends to create the implicit conclusion that the information is already contained in the genes. In other words, the developmental biologist creates the impression that the effect is already there, requiring only a perturbation to take place. Lewontin's applied biologist, by contrast, works from the implicit premise that the phenotype is something that is constructed and that it is constructed in a way that can't be determined from the genes alone. One and the same genotype can produce very different results when cultivated in different environments. As such, the seed is, for the applied biologist, a mediator. In short, there is no one-to-one mapping between genotype and phenotype. In this regard, we need to think the role that information plays in an object not as something that exists already in the entity, but as a cascade of events where information is simultaneously constructed and where information selects system-states. Needless to say, these selections have an impact on subsequent stages of development, playing a role in the determination of what subsequent information constructions are possible and excluding other possibilities.

Implicit assumptions about the transmissibility of information are rife in various forms of cultural studies as well. Whenever we speak of discourses, narratives, signifiers, social forces, and media as structuring reality and dominating people behind their backs, we speak as if persons were mere intermediaries or as if information can be exchanged without remainder. In other words, we ignore the manner in which systems are closed and how there is always a gap between cause and effect. Yet social systems, which are always themselves objects or substances, have a tough go of it as the objects of which these objects are composed never quite cooperate. All communication, as Lacan said, is miscommunication. And if this is the case, then it is because all systems produce their own information according to their own organization. As a consequence, every object or system is beset by its own system internal entropy as a consequence of the other objects or systems of which it is composed. Because objects are not intermediaries but rather mediators, the elements that a system constitutes never quite behave in the way the system anticipates.

The point here is that society cannot, as Latour said, be treated as an explanation but is precisely what has to be explained. [217] What is remarkable is that any stable social relations ever emerge at all. In A Sociological Theory of Communication, Loet Leydesdorff raises a similar question with respect to the self-organization of scientific discourse. How is it, we might ask, that something like a Kuhnian paradigm comes into existence? Leydesdorff proposes that first we have a field of heterogeneous communication acts, or a field that might be characterized by a high degree of entropy. Now, one of the remarkable and important features about human communication is that it is self-reflexive. That is, we can communicate about our communications or talk about our talk. At the second stage, reflexive discourse begins to set in. As Leydesdorff puts it,

With the reflexive moment of communication, distinctions and selections begin to emerge, determining a marked state or that which is selected and an unmarked state or that which is excluded. Over time, this talk about talk spreads through the community and becomes a sort of assumed background of those involved in communication, such that communications that deviate from these newly formed norms, themes, and distinctions are simply coded out as noise. In other words, a social system organizes itself and now develops its own capacity for selection at the second-order level through the manner in which talk about talk has become sedimented in those participating in the discourse.

In this way, the system thereby attains closure, both being produced by its own elements and producing its own elements. The system only comes into being from the action of those participating in the communication, but their communications begin to play a constraining role and produce new elements in the form of both new communications within the framework of the distinctions and selections produced by the system, and to produce new communicators capable of participating within that system. The production of these new elements, of course, takes place through the training of those participating in scientific discourse. The important point to keep in mind, however, is that even while such a self-organizing system comes to constitute its own elements, these elements aren't just elements. Rather, they are substances in their own right as well. As a consequence, such systems always struggle against a system-specific entropy. Communications are perpetually emerging that either diverge from the system that has emerged, or that challenge that system. In other words, the elements of the system are never simple intermediaries. Communications within the system perpetually generate surprising results as they pass through the mediators in the form of the persons participating in the discourse.

The concept of translation encourages us to engage in inquiry in a different way. Working from the premise that entities are mediators, it discourages any mode of theorizing that implicitly or explicitly treats objects as mere intermediaries such that effects are already contained within causes. As Latour suggests, all entities are treated as having greater or lesser degrees of agency by virtue of having a system-specific organization that prevents the relation between cause and effect from being treated as a simple exchange of information that inevitably produces a particular result. Likewise, in approaching entities as mediators, we are encouraged to attend to the manner in which entities produce surprising local manifestations when perturbed in particular ways and to vary the contexts in which entities are perturbed to discover what volcanic powers they have hidden within themselves. That is, we begin to investigate the manner in which substances creatively translate the world around them. In this respect, we move from the marked to the unmarked space of much contemporary thought. Rather than treating deviations from our predications as mere noise to be ignored, we instead treat these deviations as giving us insight into the way in which entities translate their world.

Notes

-

Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis,

trans. Alan Sheridan (New

York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1998) pp. 21–23.

-

Ibid., p. 22.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid., p. 21.

-

For a detailed discussion of Lacan's discourse theory, cf. Levi R. Bryant,

“Žižek's New Universe of Discourse: Politics and the Discourse of the

Capitalist,” International Journal of Žižek Studies 2.4

(2008).

-

Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis,

p. 22.

-

Latour, “Irreductions,” p. 181.

-

Ibid., p. 162.

-

Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to

Actor-Network Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) p. 39.

-

Latour, “An Attempt at Writing a 'Compositionist Manifesto'” Available at

http://www.bruno-latour.fr/articles/article/120-COMPO-MANIFESTO.pdf.

-

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the

Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995) pp. 135–169.

-

Ibid., p. 135.

-

Richard Lewontin, “Gene, Organism and Environment: A New Introduction”, in Cycles of Contingency, pp. 55–56.

-

Ibid., p. 55.

-

Susan Oyama, “Terms in Tension: What Do You Do When All the Good Words are

Taken?”, in Cycles of Contingency, pp. 182–183.

-

Latour, Reassembling the Social, p. 8.

-

Loet Leydesdorff, A Sociological Theory of Communication:

The Self-Organization of the Knowledge-Based Society (Universal

Publishers, 2003) pp. 5–6.