4. The Interior of Objects

4.1. The Closure of Objects

In chapter 2, I argued that, far from being a paradox, the very essence of objects consists in simultaneously withdrawing and self-othering. If objects simultaneously withdraw and are self-othering, then this is because, on the one hand, substances never directly manifest themselves in the world while, on the other hand, they perpetually alienate themselves in qualities and states as a consequence of their own internal dynamics and the exo-relations they enter into with other objects. In the last chapter, I analyzed the self-othering of objects in terms of the relationship between the perpetually and necessarily withdrawn virtual proper being of objects and the local manifestations of objects that take place through the internal dynamics of substance and the exo-relations they enter into with other objects. The claim that substances withdraw from one another suggests that it is impossible for objects to directly encounter one another. If this is the case, then this raises the question of how objects relate to one another or how we are to think the interior of objects with respect to other objects.

In this chapter, I will discuss the manner in which one entity, to use Whithead's vocabulary, “prehends” another entity, producing what Graham Harman has called “sensuous objects” on the interior of a real entity. Here “prehension” refers to the manner in which one entity grasps or relates to another entity. Whitehead carefully distinguishes between the subject that prehends (what I call a substance or object), what is prehended (another substance or object), and how that other substance is prehended. In this chapter, I focus on the first and third dimension of prehension in terms of autopoietic systems theory. In underlining the “how” of how one substance prehends another entity, Whitehead implicitly captures the sense in which entities or substances withdraw from one another insofar as no entity encounters another entity in terms of how that entity itself is, but rather every entity reworks “data” issuing from other entities in terms of the prehending substance's own unique organization. However, the position I develop here diverges markedly from Whitehead's own ontology in rejecting the thesis that in “the analysis of an actual entity [...] into its most concrete elements” the entity is disclosed in its most concrete elements “to be a concrescence of prehensions”. [151] While substances do indeed prehend other entities, substances must exist, it is argued, for these prehensions to take place. In other words, I seek to maintain a much stronger distinction between the subject/substance doing the prehending and the how of prehensions than the one Whitehead seems to suggest in his thesis that substances are a concrescence of prehensions. Part of this distinction was already developed in the last chapter with respect to the endo-structure of objects or their being as multiplicities. While prehensions can, as we will see, lead to the modification of the endo-structure of objects, the point throughout my analysis of inter-object relations is that objects must have a structure for the “how” of prehensions to take place at all and that this endo-structure constitutes the substantiality of objects.

It is to this issue that I now turn by drawing on the resources of autopoietic systems theory as developed by Maturana, Varela, and especially Niklas Luhmann. At the outset, it is important to note that my thesis is not that all objects are autopoietic machines. In their early founding essay, “Autopoiesis: The Organization of the Living”, Maturana and Varela distinguish between autopoietic machines and allopoietic machines. [152] Later I will explain the distinction between these two types of objects in greater detail, but for the moment it is sufficient to note that when Maturana and Varela refer to autopoietic machines, they are referring to living objects, while when they refer to allopoietic machines they are referring to non-living objects. Luhmann expands the domain of the autopoietic beyond living organisms to include social systems within the purview of autopoiesis, but for the moment this rough and ready distinction is sufficient for our purposes. With a few qualifications, I accept Maturana and Varela's distinction between autopoietic and allopoietic machines. However, if the work of Luhmann is so vital to this project, then this is because he ontologizes autopoietic systems, treating them as real entities, whereas Maturana and Varela advocate a radical constructivism that treats autopoietic systems as constructed by an observer. As Luhmann writes at the beginning of the first chapter of the sublime Social Systems, “[t]he following considerations assume that there are systems. Thus they do not begin with epistemological doubt”. [153] For Luhmann, systems are really existing objects in the world. I believe that I have shown in the first chapter why, following Roy Bhaskar, this supposition is warranted.

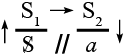

Additionally, it might come as a surprise to enlist a thinker like Niklas Luhmann in defense of object-oriented ontology. In essays like “Identity—What or How?” Luhmann levels a substantial critique against the very idea of ontology. There Luhmann remarks that “ontology is understood to be a certain form of observing and describing, to wit, that form that consists of the distinction between being and nonbeing”. [154] A moment later, Luhmann goes on to remark that “[a]mong the consequences of an ontological dissection of the world, one that differentiates being and nonbeing is this one: that the identity of what is [des Seienden] must be presupposed”. [155] I will discuss Luhmann's concept of distinction in more detail in the next section. Here what is to be noted is the manner in which Luhmann deconstructs ontology. Luhmann's point is that a particular distinction precedes the identity of an entity, such that the identity of an entity is an effect of the distinction that allows for observation, not a substantial reality that precedes observation. To understand Luhmann's point we must refer back to Spencer-Brown's calculus of forms. Spencer-Brown opens Laws of Forms with the thesis that indication is only possible on the basis of a prior distinction. As Spencer-Brown writes, “[w]e take as given the idea of distinction and the idea of indication, and that we cannot make an indication without drawing a distinction”. [156] An indication might be, for example, a reference to anything in the world. Spencer-Brown's point is that any indication requires a distinction if the indication is to be made. A distinction cleaves a space in two, defining an outside and an inside. For example, we can imagine a piece of paper populated by a plurality of x's. We draw a circle on this paper (the distinction), and can now indicate x's within the circle and x's outside of the circle. Every distinction thus contains a marked and an unmarked space. The marked space is what falls within the distinction (in this instance, what is inside the circle), while the unmarked space is everything else. This unity of marked and unmarked space generated by a distinction is what Spencer-Brown calls a “form”. There's a very real sense in which distinction is “transcendental” with respect to indication. Form is the condition under which indication is possible. As a consequence, the indicated does not precede the distinction, but is the condition under which the indicated comes into being for the system drawing the distinction. The point, of course, is that while distinctions or forms obey rigorous laws once made, the founding distinction itself is contingent in that other distinctions could have always been made.

By analyzing ontology in terms of how its indications are possible through a prior distinction, Luhman, in effect, deconstructs the grounding premise upon which ontology, as he understands it, is based. By tracing ontology back to the being/non-being distinction upon which it becomes possible to observe beings as identical, Luhmann effectively shows how this distinction is contingent such that identity is no longer the ground of being but an effect of a distinction that enables observation. The point, then, is that insofar as distinctions are contingent, they can be drawn otherwise, producing other objects as effects. As a consequence, objects become not autonomous substances that exist in their own right, but rather what Heinz von Foester called “Eigenvalues”. [157] As von Foester articulates the concept,

In other words, the object is not something that exists substantially in its own right, but is rather something that is constructed by the cognizing system through the production of stable equilibria in perception that can be returned to again and again. Elsewhere, Gotthard Bechmann and Nico Stehr sum up this line of thought when they remark that Luhman “describes the old European style of thought as concerned with the identification of the unity underlying diversity [...] Ontology refers to a world existing objectively in separation from subjects aware of it, capable of unambiguous linguistic representation”. [159] It is precisely this model of being that Luhmann challenges.

What we have here is a variant of the epistemic fallacy and actualism as discussed in the first chapter. In treating objects as Eigenvalues, Luhmann conflates substances with what substances are for a particular observing system. However, he cannot coherently get by without the category of substance. Although Luhmann everywhere focuses on epistemological issues, he requires the existence of systems in order to launch these epistemological inquiries. These systems are characterized by unity, autonomy, and endurance, which are precisely the marks of substance. As a consequence, it is necessary to distinguish between substances as such and what other substances are for a substance. Here onticology and object-oriented philosophy encounters an unexpected ally in the anti-realism of autopoietic theory and Luhmann's autopoietic systems theory in particular. Insofar as Luhmann's systems are characterized by autonomy, they avoid the holism of relationism and therefore present us with a picture of the universe that is parceled or composed of units. As I argued, following Graham Harman, in the last chapter, objects are characterized by withdrawal such that they never directly encounter one another. In their account of how systems always encounter other systems in terms of their own organization, Luhmann and autopoietic theory provide onticology and object-oriented philosophy with powerful conceptual tools for fleshing out the concept of withdrawal. The sort of ontological realism Bechmann and Stehr rightly denounce only pertains to those accounts of substance premised on presence. Yet where substances perpetually withdraw from other substances and from themselves such that they are characterized by closure, we encounter an ontology adequate to the critique of ontotheology and the metaphysics of presence.

What interests me in autopoietic systems theory is not so much its account of life or society, as its account of operational closure. As Maturana and Varela elsewhere define it, “their identity [the identity of autopoietic machines] is specified by a network of dynamic processes whose effects do not leave that network”. [160] The concept of operational closure as it applies to autopoietic machines embodies two key claims: First, the claim is that the operations of an autopoietic system refer only to themselves and are products of the system itself. For example, if, as Luhmann has argued, social systems are composed entirely of communications, if communications are the elements that compose social systems, then communications refer only to other communications and never anything outside of themselves. Here communication is not something that takes place between systems but is strictly something that takes place in a system. Another way of putting this would be to say that a system cannot communicate with its environment and an environment cannot communicate with a system.

Second, the claim is that autopoietic systems are closed in on themselves, that they do not relate directly to an environment, that they do not receive information from an environment. As a consequence, it follows that information is not something that pre-exists an autopoietic machine, waiting out there in the world to be found. To be sure, objects outside an autopoietic machine can perturb or irritate an autopoietic machine, but this perturbation or irritation does not, in and of itself, constitute information for the system being perturbed. Rather, any information value the perturbation takes on is constituted strictly by the distinctions belonging to the organization of the autopoietic machine itself. As I argue in what follows, this closure of machines or objects in terms of perturbations is not unique to autopoietic machines, but to both autopoietic machines and allopoietic machines. Both autopoietic and allopoietic machines possess only selective relations to the world around them, such that both self-referentially constitute that to which they're open. Thus, while allopoietic machines do not reproduce themselves through their own operations as is the case with autopoietic machines, allopoietic machines nonetheless constitute the way in which they are open to other entities in the world.

In “Autopoiesis: The Organization of the Living”, Maturana and Varela argue that “[a]n autopoietic machine

The unity of a system is what I call the system's “endo-consistency”, its virtual proper being, or a multiplicity. As unities, systems, whether allopoietic or autopoietic, are substances. Autopoietic machines, systems, or substances are unique in that not only are they unities, not only are they operationally closed to the rest of the world, but they also constitute their own elements. As Luhmann puts it elsewhere, “[i]n contrast to what ordinary language and conceptual tradition suggest, the unity of an element [...] is not ontically pre-given. Instead, the element is constituted as a unity only by the system that enlists it as an element to use it in relations”. [162]

Perhaps no one has gone further in formalizing, radicalizing, and developing the implications of autpoietic systems theory than Luhmann in his autopoietic sociological theory. Although I will here discuss elements of Luhmann's sociological theory, it should be borne in mind that my main aim is to outline the general features of autopoietic and allopoietic systems, rather than to focus on Luhmann's conception of society as an autopoietic system. Before proceeding, it is important to note that there are significant differences between how Maturana and Varela think autopoietic systems, and how Luhmann thinks them. For Maturana and Varela, autopoietic machines are homeostatic in character. “Autopoietic machines are homeostatic machines”. [163] That is, they are systems that attempt to maintain a particular equilibrium across time. By contrast, Luhmann's autopoietic machines, at least in the case of meaning systems, are inherently characterized by unrest. “[W]e begin, without attempting reductive 'explanation,' from the fundamental situation of basal instability (with a resulting 'temporalized' complexity) and assert that all meaning systems, be they psychic or social, are characterized by such instability”. [164] In a communication system, for example, the system aims not simply at maintaining equilibrium or homeostasis, but rather it is always necessary to find something new to say if the system is to continue to exist. Consider, for example, a conversation. Were the participants in the conversation to simply keep repeating themselves, the conversation would cease. It's necessary to find something new to say for the conversation, as a system, to continue its existence. Indeed, Luhmann will remark that both absence and remaining unchanged can therefore function as impetuses for change. As Luhmann remarks,

The key problem for any autopoietic system is how to get from one element to another in the order of time. Every autopoietic system is challenged by entropy and must find ways of staving off a collapse into entropy or disorganized complexity. The elements of autopoietic machines within the Luhmannian framework are events. As events, they disappear as soon as they occur. As a consequence, every autopoietic machine faces the problem of how it can reproduce itself or generate new elements from moment to moment. Confronted with an absence of change, that absence of change itself becomes the instigator of new events or elements in the ongoing autopoiesis of the system. Only through the production of subsequent elements or events is the autopoietic machine able to persist or continue existing. It is for this reason that meaning systems, at least, must necessarily be basally unstable. Here it should be noted that the substance of autopoietic systems resides not in the materiality of its parts—these parts can be and are replaced while the substance continues to exist—but rather by virtue of their structure or organization which I have referred to as multiplicities or the “endo-structure” of substances.

In arguing that the elements that compose autopoietic systems are not ontically pre-given, it is argued that these elements are not themselves substances, but rather only exist for the endo-consistency of the substance or multiplicity that constitutes them. The point is not that nothing exists apart from a system—everything must be built out of other things as Aristotle observed—but rather that what constitutes an element for a system does not pre-exist the system that constitutes or constructs it. Luhmann observes that we “must distinguish between the environment of a system and systems in the environment of this system”. [166] If the distinction between the environment of a system and systems in the environment of a system is crucial, then this is because the former refers to how one substance encounters other substances in the world through its own closure and organization, while the latter refers to actually existing systems or substances that would exist regardless of whether or not the system encountering them existed. These actually existing systems, whether autopoietic or allopoietic themselves, can and do serve as material through which systems constitute their elements.

In his sociological systems theory, Luhmann develops the closure of systems to dramatic effect. For autopoietic systems theory

Insofar as onticology maintains that substances are fully autonomous, it parts ways with Luhmann in the thesis that substances or systems cannot exist independently of an environment. Nonetheless, onticology also recognizes that many systems would produce less than ideal local manifestations were they separated from an environment of exo-relations with other entities of a particular sort. A cat, for instance, is unable to exercise all sorts of powers of acting in the absence of oxygen. The important point here is that the distinction between system and environment is self-referential. Although this distinction refers to two domains (system and environment), the distinction itself originates from one of these domains: the system. The distinction between system and environment is a distinction drawn by each system. This is not only one of the origins of the operational closure of systems, but is also a condition for the autonomy of systems as individual and independent substances.

In the case of autopoietic machines, the distinction between system and environment emerges “because for each system the environment is more complex than the system itself”. [168] As a consequence, “[t]here is [...] no point-for-point correspondence between system and environment”. [169] Were there a point-for-point correspondence between system and environment, there would be no distinction between systems and their environments. Moreover, this would require systems to respond or react to every event that takes place in their environment, thereby overburdening the system. Consequently, one way of thinking about autopoietic systems or substances is as strategies of selection or continuance within an environment that they are unable to completely anticipate and which they are certainly unable to dominate or master by virtue of the greater complexity that each environment possesses when compared to the complexity of systems.

A similar point holds with respect to the elements that systems produce or constitute. In the case of elements composing the endo-consistency of a multiplicity or system, these elements only exist in relation to one another. “Just as there are no systems without environments or environments without systems, there are no elements without relational connections or relations without elements”. [170] Here we must carefully distinguish between substances and elements. Elements are always elements for a substance. They only exist as elements within the endo-structure or endo-composition of a system and do not, as we have seen, have any independent ontological existence of their own. Substances, by contrast, always enjoy an autonomous ontological existence in their own right, and therefore only exist in relations that are external to them. That is, substances are capable of breaking with their relations and entering into new relations, or of existing completely without relations at all. With an increase in the complexity of a system or the number of elements it must maintain to exist, special problems emerge. As Luhmann observes, “when the number of elements that must be held together in a system or for a system as its environment increases, one very quickly encounters a threshold where it is no longer possible to relate every element with every other element”. [171]

Three interesting consequences follow from this endo-complexity of systems. First, insofar as it is not possible to feasibly connect every element of the system to every other element, it follows that systems must maintain selective relations among their elements, such that, they “[omit] other equally conceivable relations [among elements]”. [172] These selective relations among elements are thus strategies for contending with an environment that is always more complex than the system itself. Luhmann emphasizes the contingency of these relations and the manner in which they involve risk. However, second, because not every element relates to every other element in a complex system, but rather relations are contingent strategies for contending with the environment, it follows that “very different kinds of systems can be formed out of a substratum of very similar units”. [173] In other words, when speaking about the virtual proper being of an object or a multiplicity, it is not so much the substance's elements that constitute their substantiality, but rather how their elements are organized or related. It is for this reason that I speak of “endo-relations” in relation to the endo-consistency of the virtual proper being of an object. Finally, third, because systems constitute their own elements it follows that “systems of a higher (emergent) order can possess less complexity than systems of a lower order because they determine the unity and number of elements that compose them”, [174] along with the relations among these elements.

One paradoxical feature of the system/environment distinction at the heart of any system, whether autopoietic or allopoietic, is that this distinction is not a distinction between two entities in their own right, but is rather a distinction that arises from one side of the distinction. In short, it is the system itself that “draws” the distinction between system and environment. As Luhmann remarks, “[t]he environment receives its unity through the system and only in relation to the system”. [175] An environment is thus an environment only for the interior of an object or substance. Two consequences follow from this: First, the environment is not a container of substances or systems that precedes the existence of substances or systems. There is no environment “as such” existing out there in the world. Put otherwise, there is no pre-established or pre-given environment to which a system must “adapt”. Rather, we have as many environments as there are substances in the universe, without it being possible to claim that all of these systems are contained in a single environment. As Timothy Morton puts it in a very different context, “[t]here is no environment as such. It's all 'distinct organic beings.'” [176] The environment is not a container lying there present at hand, awaiting the system to adapt to it. Rather, there are as many environments as there are systems, and the environment is nothing more than other systems that in turn “draw” their own system/environment distinctions. As we will see in chapter six, this leads to the conclusion that the world does not exist. Second, the distinction between system and environment is, as a consequence, paradoxical and self-referential. Insofar as the distinction between system and environment is a distinction “made” by the system, this distinction is also self-referential or a distinction belonging to the system itself. As we will see in a moment, this has significant consequences for how systems or substances relate to other entities.

To illustrate these points, take the example of the humble tardigrade. The tardigrade is a microscopic multicellular organism with eight legs, two eyes, and antennae and which looks somewhat like an alien pig. The tardigrade is particularly interesting because it is capable of surviving extreme variations of heat and cold without dying. Thus, for example, it can be subjected to extremely high temperatures such as those that occur when a meteor enters the Earth's atmosphere. When this occurs, all the water in the tardigrade’s body steams away and it withdraws its legs into its trunk, becoming a hard pellet that appears to be dead. However, if water is introduced back into the tardigrade's environment, the tardigrade plumps back up and is walking around again within a few hours as if nothing happened. Returning to some themes of the first chapter, it is highly unlikely that substances like cats or humans belong to the environment of the tardigrade. As a microscopic organism, it perhaps crawls in and out of the different fissures in the skin and bodies of larger scale organisms, completely unaware that such organisms even exist. Nor, we can say, do these larger scale organisms function as that to which the tardigrade must adapt. The point is not that these larger scale organisms don't exist or that tardigrades get to decide what exists and what does not exist. To claim this, one would be confusing the environment of a system with systems or substances in a system's environment. Rather, the point is that substances maintain only selective relationships to their environment.

The self-referentiality of the system/environment distinction is one of the meanings of operational closure, and is common to both allopoietic substances and autopoietic substances alike. It is a common feature of all substances that they are one and all closed to the world, relating to systems in their environment only through their own distinctions or organization. As a consequence of this closure, systems or substances only relate to themselves. Put differently, while substances can enter into exo-relations with other substances, they only do so on their own terms and with respect to their own organization.

Luhmann draws startling conclusions from this thesis in his analysis of society. If societies are autopoietic systems or substances, and if autopoietic substances both constitute their own elements and are operationally closed, then it follows that humans are not a part of society. Luhmann's conception of society is thus radically at odds with that found in the humanist tradition. As Luhmann writes,

Here it is important to note that, far from denying the existence of humans, Luhmann is defending their existence. Were we to claim that humans are products or effects of society as Althusser, for example, does in his essay on the ideological state apparatus and elsewhere, we would be conflating the existence of humans with that of elements in the system of society. However, just as societies are operationally closed systems, so too are humans. “If one views human beings as part of the environment of society (instead of as part of society itself), this changes the premises of all traditional questions, including those of classical humanism”. [178]

Humans belong not to society, but rather the environment of society. Paradoxically, then, humans are outside of society. For Luhmann, society, by contrast, consists of communications and nothing but communications. And insofar as humans belong to the environment of society, they do not participate in society. As Luhmann puts it elsewhere, “one could say that the environment of the social system cannot communicate with society”. [179] Likewise, systems or substances cannot communicate with their environments. If this is the case, then it is because systems only relate to themselves and “[i]nformation is [...] a purely system-internal quality. There is no transference of information from the environment into the system”. [180] Put a bit differently, systems or substances communicate only with themselves. If, then, society is not composed of persons or humans, what is it composed of? As Luhman remarks, “[i]n the end, it is always people, individuals, subjects who act or communicate. I would like to assert in the face of this that only communication can communicate and that what we understand as “action” can be generated only in such a network of communication”. [181] The elements that compose society consist of nothing but communications and the production of new communications in responses to communications. It is not persons that communicate, but rather communications that communicate.

To be clear, Luhmann is not advancing the absurd thesis that societies can exist without humans. Social systems are autonomous from humans, they are distinct substances in their own right, but they require the perturbations or irritations of humans in order to come into existence. As Luhmann puts it in Social Systems,

How, then, are we to understand this jaw droppingly counter-intuitive thesis that humans do not belong to society and that they are incapable of communication insofar as only communications communicate? Elsewhere Hans-Georg Moeller explains this point well:

Minds are operationally closed with respect to brains. Minds relate to themselves through thought alone, whereas brains relate to one another through electro-chemical reactions alone. Neither of these systems knows anything of the other. Likewise, the communications of society are operationally closed with respect to minds such that communications can respond only to communications. In each of these cases we have systems and their environments.

To illustrate Luhmann's thesis, I turn to the simple example of a humble dialogue. For the last few years I have been fortunate to have the friendship of my colleague Carlton Clark, a rhetorician at the institution where I teach. Within a Luhmannian framework, this dialogue is not a communication between two systems (Clark and myself), but rather is a system in its own right. In this respect, Clark and I belong not to the system of this dialogue, but to the environment of this dialogue. We are outside the system constituted by this dialogue insofar as neither of us have access to the thoughts or neural system of the other. What communicates in this dialogue is thus neither Clark, nor myself, but rather communications. Moreover, this dialogue continually makes self-references (references to events that are within the dialogue and communications that have been made in the past of the dialogue) and other-references (references to the environment of the dialogue). In other words, the dialogue is organized around what is internal to the dialogue itself, to the system that has emerged over time, and to what is outside the dialogue or in the environment of the dialogue constituted by the dialogue itself. An event that has taken place at the college, for example, is treated as belonging to the environment of the dialogue, as outside the dialogue, while it can also become a topic within the dialogue that is related to according to the meaning-schema that the dialogue has developed over time. Over the course of this lengthy dialogue, the dialogue as a system has evolved its own distinctions, themes, topics, and ways of handling these themes and topics. Some of these topics and themes include rhetoric, teaching, philosophy, family, college politics, politics, and so on. The distinctions inhabiting the dialogue are the implicit ways in which these themes and topics are handled or the meaning schema that regulate the dialogue. Events in the environment of the dialogue can perturb or irritate the dialogue, providing stimuli for new communicative events. For example, a new book can be published that becomes a stimulus for the production of new communications within the system. However, the publication of this new book does not enter the dialogue qua book, but is integrated into the dialogue according to the distinctions and organization of the dialogue itself. In this respect, the dialogue is an entity itself that constitutes its own elements (the communication events that take place within it) and that is something Clark and I are bound up in without being parts or elements within the dialogue. Just as Meno is not himself an element in Plato's dialogue Meno, Clark and Bryant are not elements in this dialogue.

From our discussion of the operational closure of autopoietic objects, we have thus learned four important features of the nature of objects. First and foremost, objects relate only to themselves and never to their environment. Here it is as if the universe were populated by solipsists, Aristotle's First Cause, Unmoved Mover, Leibnizian monads, or, as Harman has put it, vacuums. Second, every substance or system is organized around a distinction between system and environment that the system itself draws. As a consequence, this distinction between substance and environment is self-referential. Third, autopoietic substances, in contrast to allopoietic substances, constitute their own elements or perpetually reproduce themselves through themselves or their own activities. In the case of autopoietic substances, the elements composing the autopoietic substance constitute one another and are constituted by one another. Finally, substances are such that we can have substances nested within substances, while these substances nested within substances nonetheless belong to the environment of the substance within which they are nested. This is the case, for example, with societies. Humans are nested within societies but do not belong to the social system but rather the environment of the social system. In many respects, humans are the matter upon which social systems draw to construct themselves insofar as they constantly perturb social systems, without the humans being the ones doing the constructing. Instead, it is communication that constructs communications. To see this point, think of the way in which our intentions get entangled in communications. We make, for example, a claim that contradicts some claim we made in the past and the subsequent communication that follows points out this contradiction, regulating, as it were, our subsequent communications. We find an analogous case of substances nested within substances with respect to the relationship between cells and the body. Each cell is its own closed autopoietic system, yet the body employs cells in the construction of itself through its own autopoietic processes. Here we encounter, once again, the strange mereology of onticology and object-oriented philosophy where objects can be nested in other objects while nonetheless remaining independent or autonomous of those objects within which they are nested. This mereology destroys organic conceptions of both society and the universe, where all substances are thought of as parts of an organic whole.

One important consequence that follows from the operational closure of substances is that this closure renders unilateral control of one substance by another substance impossible. As Luhmann puts it,

In this context, Luhmann is speaking of subsystems of a system and how they relate to one another. Because each subsystem of a system is itself founded on an operationally closed, self-referential system/environment distinction, one subsystem of the social system cannot control another subsystem of the social system. For example, the political subsystem cannot control the economic subsystem because each subsystem relates to its own environment in its own unique way as a function of its peculiar organization. The economic subsystem of the social system, for example, encounters perturbations from the political subsystem of the social system in terms of economics. What holds for subsystems within a larger system holds equally and even more so for relations between different systems or substances. Each substance interacts with other substances in terms of its own peculiar organization. As a consequence, there can be no unilateral transfer of actions from one system to another system, such that the content or nature of the initiating system or substance's action is maintained as identical. As we will see later in the next chapter, this requires us to rethink relations of constraint between substances in what Timothy Morton has called “meshes” or networks of substances.

4.2. Interactions Between Objects

If, then, objects or substances are operationally closed, if they only relate to themselves, how do objects interact? While substances are closed to one another, they can nonetheless perturb or irritate one another. And in perturbing or irritating one another, information is produced by the system that is perturbed or irritated. However, here we must proceed with caution, for information is not something that exists out there in the environment waiting to be received or detected. Moreover, information is not something that is exchanged between systems. Often we think of information as something that is transmitted from a sender to a receiver. The question here becomes that of how it is possible for the receiver to decode the information received as identical to the information transmitted. However, insofar as substances are closed in the sense discussed in the last section, it follows that there can be no question of information as exchange. Rather, information is purely system-specific, exists only within a particular system or substance, and exists only for that system or substance. In short, there is no pre-existent information. Instead, information is constructed by systems. As Luhmann remarks, “above all what is usually called 'information' are purely internal achievements. There is no information that moves from without to within a system”. [185] Elsewhere, Luhmann remarks that “[i]nformation is an internal change of state, a self-produced aspect of communicative events and not something that exists in the environment of the system”. [186] Consequently, information is a transformation of perturbations of an object into information within a system.

This point can be illustrated with respect to my relationship with my cats. When my cat rubs against me or jumps on my lap these events constitute perturbations for me. However, as a system I translate these perturbations into information, registering them as signs of affection. In response, I pet my cat to show my affection. By contrast, my cats might merely be seeking warmth or marking me with their scent so as to establish territory. The point here is that no identity of shared information need be present for this interaction to take place and maintain itself. My cat and I are perhaps occupied with each other for entirely different reasons, completely unaware that we have different reasons, yet an interaction and communication still takes place.

However, two points must be made here: first, substances are not capable of being perturbed in any old way. My eyes, for example, are not capable of being perturbed by infrared light. Dogs and cats, as I understand it, have a very limited range of color vision. Neutrinos pass straight through most things on the planet Earth. Rocks, as far as I know, are unable to see color at all. Electric eels sense the world through various electric signals, whereas cats very likely have no sense of what it would be like to experience the world in such terms. Consequently, all substances, whether allopoietic or autopoietic, are only selectively open to the world. Second, and in a closely related vein, not all perturbations are transformed into information. In the next section we will see that allopoietic machines and autopoietic machines relate to information events in very different ways. In the case of autopoietic machines, however, it is always possible for perturbations to which a system is open to nonetheless produce no event of information such that the perturbation is coded merely as background noise. As I am writing this, for example, my three-year-old daughter is dancing about the room, yet I scarcely notice her at the moment.

Information is thus not something that exists in the world independent of the systems that “experience” it, but is rather constituted by the systems that “experience” it. Nonetheless, this constitution does not issue entirely from the system constituting the information itself. Information is, as it were, a genuine event that befalls a substance or happens to a substance. The perturbations that function as the ground for the production of information can issue from either the environment or transformations in the system itself, but they are always events that must take place for information production to occur. Following Gregory Bateson, Luhmann treats information as a difference that makes a difference. [187] If information is a difference that makes a difference then this is because it selects system-states. As Luhmann writes, “[b]y information we mean an event that selects system states. This is possible only for structures that delimit and presort possibilities. Information presupposes structure, yet is not itself a structure, but rather an event that actualizes the use of structures”. [188] Information is thus not so much a property of substances themselves, but is rather something that occurs within substances. In “Pathologies of Epistemology”, Bateson articulates this point nicely. As Bateson writes,

- The system shall operate with and upon differences.

- The system shall consist of closed loops or networks of pathways along which differences and transforms of differences shall be transmitted (What is transmitted on a neuron is not an impulse, it is news of a difference.)

- Many events within the system shall be energized by the respondent part rather than by impact from the triggering part.

- The system shall show self-correctiveness in the direction of runaway. Self- correctiveness implies trial and error. [189]

Elsewhere, Bateson remarks that differences are “brought about by the sort of 'thing' that gets onto the map from the territory”. [190] Here we can think of map and territory as system and environment, where the territory is always more complex than the map. Bateson's point seems to be that difference is not an identical unit that is transmitted from one thing to another—for example, from one neuron to another—but rather is a perturbation or irritation that is then transformed into information by the receiving entity. As such, information is constituted by the systems receiving the differences. Situated within the context of the thing-schema developed in chapter three, information, as that event that selects system states, actualizes virtual potentials belonging to the virtual proper being of an object, which are then deployed to produce local manifestations.

Later Luhmann will remark that “information is nothing more than an event that brings about a connection between differences”. [191] Although Luhmann does not develop his thesis in this way, we can characterize the linkage of difference that events of information generate in terms of three dimensions. First, information differentially links an object to itself in a relation between the withdrawn virtual proper being of the object and its local manifestations. Here we encounter the process by which local manifestations take place within an object; or rather, the process of self-othering and withdrawal characteristic of every object whether that object be autopoietic or allopoietic. Through the selection of a system state, information affects a self-othering in the object whereby the virtual dimension of the object simultaneously withdraws and a quality is produced. These information events can take place both internally or as a result of external interactions of the object with other objects. Second, events of information link difference to difference through the linkage of perturbations to information. Perturbations are never identical to information precisely because information is object-specific, whereas the same perturbation can affect a variety of different objects while producing very different information for each object perturbed. Finally, third, events of information link difference to difference through a linkage of different withdrawn objects to one another. No object directly encounters another object precisely because all objects are operationally closed. As a consequence, no object is capable of representing another object or of functioning as a pure carrier of the perturbations issued from another object. This is because objects always transform or translate perturbations. Nonetheless, information links the different to the different in a substance-specific manner wherever substances relate to one another.

Because information is not a property of a substance, but rather an event that befalls or happens to a substance and which selects a system state, “[i]nformation [...] always involves some element of surprise”. [192] For this reason, information plays a key role in the evolution and development of autopoietic systems, contributing to the formation of new forms of organization within existing autopoietic substances. Insofar as information selects object-states it always carries an element of surprise. As Luhmann puts it,

Here whether or not a bit of information functions as information depends on the preceding object-state of the substance in question. If, after hearing that the value of the dollar has fallen, I shift to another news channel and hear the same thing once again, this bit of information has lost its status as information because it no longer selects a new cognitive state within my mental system. However, if I hear this bit of information a week or month later it can once again become information by virtue of how it contrasts with my preceding mental state. The value of the dollar has fallen again. And if this information selects a system state, this might be in the form—were I an investor—of not selling stocks at this particular time by virtue of the fact that I won't get a good return on my sale.

In order for information to take place as an event within a system it is thus necessary for distinctions to be operative within the system. As we will recall from the last section, indication can only occur based on a prior distinction that cleaves a space into a marked and unmarked space the unity of which Spencer-Brown refers to as a “form”. Information is a sort of indication that an environment “forces”, as it were, on a system. For example, when I awoke early this morning I saw that it was raining. Certainly I didn't conjure this weather state into existence through my own whim. However, for this weather state to function as information, there had to be a prior distinction at work in my cognitive system. Perhaps this distinction consists of something like the distinction between precipitation (marked state) and non-precipitation (non-marked state). It will be noted that this distinction doesn't tell me in advance what states exist in my environment. It doesn't tell me in advance whether the precipitation will be a torrential downpour, snow, sleet, a drizzle or whether the day is sunny or overcast. Nonetheless, for cognitive and communication substances, it is the distinction that allows for any of these states, and many others besides, to take on significance. Here the environment selects how this distinction will be actualized or filled with content, yet the prior distinction predelineates what environmental states can serve this function for the system.

There are a variety of ways in which such events select system-states. Not only do such events actualize the operative distinction in a particular way (“it's a heavy downpour!”), but they also play a role in subsequent operations of the system. For example, upon seeing that it is raining, I now conclude that I don't need to water my garden for the next couple of days, that I need to bring an umbrella if I go out, and that I need to dress in a particular way to keep warm and dry. In short, the information leads to subsequent events within the system.

Here it is important to note that the subsequent events that take place within the system are not of a determinate nature but could unfold in a variety of different ways. This is especially true of systems organized around meaning such as psychic systems and social communications systems. As Luhmann argues,

Here, in his discussion of “experience”, we encounter Luhmann's basic concept of meaning. Meaning is the unity of a difference between actuality and potentiality. Each actualized meaning simultaneously refers beyond itself to other meanings that could have been actualized. For example, while I conclude that since I am going out I must carry an umbrella, this actualization still refers beyond itself to the possibility of staying in. The phenomenon of meaning is such that while it actualizes a meaning, the negated or excluded alternatives remain, even though under the sign of negation. This is one reason every meaning has an air of contingency about it. Every meaning is haunted by the other potential meanings it has excluded. And this, incidentally, is why ultimate foundations are impossible within philosophy. Insofar as meaning is the unity of a difference between actuality and potentiality, every ground that purports to function as the final ground nonetheless refers beyond itself to other excluded potentials that could have functioned as grounds.

This account of meaning provides us with the means of distinguishing between information and meaning. As Luhmann writes,

Information is an event that reduces uncertainty within a system by selecting a state based on a prior distinction (“what will the weather be like today?” “it's raining!”). Meaning, by contrast, maintains the unity of a difference between an actualized given and other potentialities or possibilities.

Because information is premised on a prior distinction that allows events in the environment to take on information value, it follows that systems, in their relation to other objects, always contain blind spots. What we get here is a sort of object-specific transcendental illusion produced as a result of its closure. As Luhmann remarks in Ecological Communication, “one could say that a system can see only what it can see. It cannot see what it cannot. Moreover, it cannot see that it cannot see this. For the system this is something concealed 'behind' the horizon that, for it, has no 'behind'“. [196] If systems can only see what they can see, cannot see what they cannot see, and cannot see that they cannot see this, then this is because any relation to the world is premised on system-specific distinctions that arise from the system itself. As a consequence of this, Luhmann elsewhere remarks that, “[t]he conclusion to be drawn from this is that the connection with the reality of the external world is established by the blind spot of the cognitive operation. Reality is what one does not perceive when one perceives it”. [197]

If reality is what one does not perceive when one perceives it, then this is because (1) objects do not relate directly to other objects, but rather relate to other objects only through their own distinctions, and (2) because objects do not themselves register the distinctions that allow them to relate to other objects in this way. Objects are thus withdrawn in a dual sense. On the one hand, objects are withdrawn from other objects in that they never directly encounter these other objects, but rather transform these perturbations into information according to their own organization. On the other hand, objects are withdrawn even from themselves as the distinction through which operations are possible, the endo-structure of objects, withdraw into the background, as it were, in the course of operations. When I note that it is raining, the distinction between precipitation and non-precipitation is not there before me for my cognitive system, but is rather used or employed by my cognitive system.

The transcendental illusion thus generated by the manner in which objects relate to one another is one in which the states “experienced” by a system are treated as other objects themselves, rather than system-specific entities generated by the organization of the object itself. In other words, the object treats the world it “experiences” as reality simpliciter, rather than as system-states produced by its own organization. Here it is important to note that the foregoing analysis does not require us to follow Luhmann or Spencer-Brown in the thesis that such system-states are produced by binary distinctions. All that is required is that these states be produced as a consequence of an object's endo-structure or virtual proper being. It could be that binary distinctions are only operative in “more advanced” objects such as cognitive systems and communication systems, with other systems simply having an endo-structure composed of networks of relations defining a particular organization that can only be perturbed in various ways along the lines described by Bateson in terms of a transmission (or better yet, production) of differences. It could be that “more advanced” systems are non-linear networks of this sort as well. What is important is not whether or not information is produced through binary distinctions, but rather that information is a product of the organization of the system in question, not a transfer of information as self-identical from one object to another.

Between Luhmann's account of how systems relate to the world and Graham Harman's object-oriented ontology, we find remarkable points of overlap. Like Harman's objects, Luhmann's systems are autonomous individuals that are closed and independent of other systems. In his most recent work, Harman has argued that all objects are quadruple in their structure. [198] Without going into all the details of his account of objects, Harman distinguishes between real objects and real qualities, and sensuous objects and sensuous qualities. Here we must proceed with caution, for Harman's sensuous objects 1) do not refer solely to objects that are merely fictional, and 2) are not restricted to humans and animals alone. Rather, all objects, whether animate or inanimate, relate to other objects not as real objects, but as sensuous objects. Evoking a sort of quasi-Lacanianism, we can say that “a sensuous object is an object for another object”. Sensuous objects are not the real object itself, but are, rather, what objects are for other objects. In this respect, sensuous objects are very similar to Luhmann's information events and system-states.

Unlike real objects, Harman's sensuous objects exist only on the interior of a real object. These sensuous objects can arise both from the interior of the real object that encounters them or from other real objects. In Prince of Networks, Harman gives the examples of “Monster X” and a friend’s cat that he is taking care of. [199] Monster X is a monster that Harman generates through his imagination and whose qualities he refuses to share with us (he assures us that this is the most fearsome and frightening monster ever imagined). Now, unlike a real object, Monster X only exists in the interior of Harman's imagination, is not withdrawn, and ceases to exist when he falls asleep at night or ceases thinking about it. Monster X is capable of acting on Harman through a sort of auto-affection of Harman by Harman, but it is not an object out there in the world that is capable of being perturbed by other objects. The case is similar with the cat Harman was taking care of when writing about Monster X. The cat is, of course, a real entity out there in the world that is an “autonomous force unleashed in Harman's apartment” regardless of whether he is aware of its activities. However, for Harman, the cat is also a sensuous object that exists on the interior of Harman. Like Monster X, the cat qua sensuous object ceases to exist when Harman ceases to think about it or when he goes to sleep. However, unlike Monster X, the cat qua real object continues to be an autonomous force unleashed in the world even when he ceases to think about it.

In this context, the important point to take away from Harman's quadruple objects is that objects only ever relate to other objects through sensuous objects. No object ever encounters another object as a real object. If we translate Harman's thesis into Luhmannian terms, we can say that systems or real objects only ever encounter other objects as information and system-states. Harman's fearsome Monster X would be an example of a system-state. Monster X is not an event produced within a system as a consequence of a perturbation from the environment, but rather is a meaning-event that Harman produced on his own. By contrast, Harman's friend's cat is a combination of information and meanings. When the cat perturbs him in a particular way, the cat functions as information, selecting a particular system-state within Harman. Various thoughts Harman might have about the cat would be meaning-events produced by Harman. Yet in both cases, what we have are purely internal system states that differ from whatever other objects might happen to be in the environment. As a consequence, we only ever encounter other objects as sensuous objects rather than real objects, such that we are both withdrawn from these real objects and they are withdrawn from us.

4.3. Autopoietic and Allopoietic Objects

Returning to the themes of the last chapter, we can now situate the functioning of systems with respect to how they produce and respond to information in terms of virtual proper being and local manifestation. As I observed in 4.1, Maturana and Varela distinguish between autopoietic and allopoietic machines. Autopoietic machines are machines or objects that produce their own elements and “strive” to maintain their organization across time. Our bodies, for example, heal when they are cut. The key feature of autopoietic machines is that they produce themselves. Not only do autopoietic machines constitute their own elements, but they paradoxically constitute their own elements through interactions among their elements. By contrast, allopoietic machines are machines produced by something else. Generally the domain of allopoietic machines refers to inanimate objects. Here it's worth noting that the distinction between autopoietic objects and allopoietic objects is not a hard and fast or absolute distinction, but is probably a distinction that involves a variety of gradations or intermediaries.

Despite the differences between allopoietic machines and autopoietic machines, I want to argue that both undergo actualizations through information and both involve system/environment distinctions that constitute their relations to other objects. Here a major difference between autopoietic machines and allopoietic machines would be that allopoietic machines can only undergo actualization through information, whereas autopoietic machines can both be actualized in a particular way through information and can actualize themselves in particular ways through ongoing operations internal to their being. Here it might appear strange to speak of information in relation to allopoietic or inanimate objects. However, we must recall that information is neither meaning, nor is information a message exchanged between objects. Rather, as we have seen, information is a difference that makes the difference or an event that selects a system state. In this regard, there is no reason to restrict information to autopoietic objects, for such events take place within allopoietic objects as well.

Before proceeding to discuss the differences between how these two types of objects relate to information, it is important to make some points regarding the system/environment distinction as it is deployed in autopoietic theory. Maturana, Varela, and Luhmann tend to speak of the distinction between system and environment as a distinction that systems draw such that this distinction allows systems to observe their environment. In my view, these are conventions that should be abandoned, or rather, that should be evoked in highly system-specific contexts. Rather than claiming that systems draw distinctions between themselves and their environment—implying that there's a homunculus that does the drawing—we should instead say that systems are their distinction or form. Here it will be recalled that “form”, as Spencer-Brown understands it, is the unity of the marked and unmarked space produced by a distinction. The distinction that generates the marked and unmarked space is, of course, self-referential in the sense that it belongs to one side of the distinction: the system. Insofar as objects are autonomous and independent, they are necessarily self-referential in that their separation from the environment is produced by the object itself. It is the distinction between system and environment that both constitutes the closure of objects and their particular form of openness to other objects. In the case of more “advanced” systems like cognitive systems, social systems, and perhaps some computers, we get the ability to actively draw distinctions and follow through their consequences or what subsequent operations they generate, but in many other instances it's unlikely that systems have any real freedom in how the distinction between system and environment is constituted.

Likewise, rather than claiming that systems observe their environment through their distinctions, we should instead claim that objects interact with other systems through their distinctions. The emphasis on observation, in my view, is one of the greatest drawbacks of various strains of autopoietic theory. Observation implies a distinction between self-reference or reference to internal states of the system and other-reference or references to the environment. The distinction between self-reference and other-reference, in its turn, requires a doubling of the distinction between system and environment within the system itself. That is, systems that distinguish between self-reference and other-reference are systems where the distinction between system and environment re-enters the system that draws this distinction so that the distinction between system and environment can itself be observed. In other words, self-reference and other-reference requires a self-referential operation whereby the system observes how it observes and thereby distinguishes between what arises from within the system itself and what comes from without. Rather than simply undergoing a perturbation, I now treat this perturbation as something that issues from the environment and register that this perturbation comes from the environment. This doubling of the system/environment distinction is a necessary condition for observation.

In their discussions of autopoietic theory, Maturana and Varela often evoke cells as a prime example of autopoietic systems. However, this example, above all, indicates just why we should not talk about the self-referential distinction upon which any system or object is founded in terms of observation. Although cells cannot exist without a boundary between system and environment that is constituted self-referentially by the cell itself, it is misleading to suggest that there's any meaningful sense in which cells observe their environment or make other-references to the world independent of them. To be sure, cells interact with their environment and are, like any other system, perturbed by their environment, but there's no meaningful sense in which they refer to their environment. To suggest otherwise is to imply that entities like cells operate according to meaning. Rather than speaking in terms of observation and other-reference, both of which are far too epistemological and cognitive in their connotations, we should instead speak in terms of how systems are selectively open to their environment and how they interact with their environment. Other-reference and observation, rather, seems to be something that only emerges with more complicated systems such as tardigrades, frogs, and perhaps certain computer systems.

The term “information” is fortunate in that it contains within itself a certain productive polysemy that allows it to resonate in a variety of ways. In addition to treating information as an event that selects system states, we can also read the term “information” avant la lettre to play on the more literal connotations of the term. When we break information into its units, we can say that information refers to what is in formation. Here information refers to the genesis of local manifestations as ongoing processes rather than as fixed identities. The identity of objects is not fixed, but is rather a dynamic and ongoing identity that is in formation. While there is indeed an identity to the object, in the sense that it has a virtual endo-structure that persists across time, this identity is always manifesting itself in a variety of ways. Similarly, we can also read information as “in-form-ation”. Here information does not refer to the ongoing genesis and openness of objects—that which is “in formation”—but rather refers to the manner in which objects take on new form or come to embody new form with their actualizations in local manifestations. Returning to the distinction I drew between the topology of objects and the geometry of objects in the last chapter, information as in-form-ation here refers to the transition that takes place within an object from the domain of virtual proper being and the potentialities populating virtual proper being to the geometric actualization of a form or quality in an object. In other words, in-form-ation refers to the local manifestation of an object embodied in a specific quality.

In both allopoietic and autopoitic systems, information is an event that makes a difference by selecting a system-state. However, information functions in very different, yet related, ways in the case of allopoietic and autopoietic systems. In both cases, information is non-linear and system-specific, existing only for the system in question and as a function of the organization or endo-structure of the object. In saying that information is non-linear, my point is that it is an effect of the endo-structure of the object as it relates to its environment and how this endo-structure resonates within the field of differential relations that define that structure. Information is not in the environment, but is a product of the system perturbed by its environment. In the case of allopoietic systems, information functions to actualize a degree in the phase-space of the virtual proper being of the substance, leading to the actualization of a particular quality in a local manifestation.

Here the point I wish to make is so basic as to appear trivial. However, this point has important consequences for how we analyze allopoietic objects in the world. When an allopoietic object is perturbed in a particular way, it produces an actuality proper to the endo-structure of its being. One and the same perturbation can produce very different local manifestations in different allopoietic objects. Thus, for example, water behaves differently than rocks when hit by another object or heated up. When water is heated up, it locally manifests itself in the quality of boiling. When a rock is heated up, heat is distributed throughout the rock. When water is hit by another object, it produces waves. When a rock is hit by another object, it begins to roll and perhaps vibrates.

These are obvious and familiar points about the objects that populate our world. We all recognize, even if only implicitly, that different objects or different types of substances respond differently to one and the same perturbation. However, while this is an obvious point, it is nonetheless a point that needs to be accounted for. It is precisely this which the concepts of virtual proper being, local manifestation, and information attempt to account for. When an allopoietic object is perturbed in a particular way, information is produced as a consequence of how the object in question is organized. This information, in turn, selects a system-state which actualizes a potentiality in the virtual proper being of the object in the form of a particular quality or local manifestation.

Now, there are two important points worth making here. First, as in the case of autopoietic objects, allopoietic objects are only selectively open to their environments. Many events can occur in the environment of an object without all of these events being capable of perturbing the object and thereby being transformed into information. While rocks, for example, are certainly open to sound waves, they are not, as far as I know, open to signifiers. Uluru or Ayers Rock, for example, is in-different to its title as Uluru or any special legal status it is given. It does not get offended when a stranger that has never heard of it fails to refer to it by its proper name, it doesn't answer to its proper name, nor does it likely worry itself over any sacred or legal preferences it might gain through being Uluru. Here reference to Uluru's in-difference to its name should be taken quite literally as signifying that Uluru's name cannot select system-states within Uluru. Uluru is entirely closed with respect to its name.

Lest one conclude that this sort of closure to its name is merely a feature of the difference between culture and nature, I offer an example of (non)relations between completely natural beings as well. Neutrinos are extremely small elementary particles that travel close to the speed of light. Because neutrinos are electrically neutral, they pass through most matter completely undisturbed and without disturbing that matter. This causes, of course, massive problems in the detection of neutrinos as most detection devices we might use to detect them cannot be perturbed by them due to the electric neutrality of the neutrino. Here the neutrino is a perfect example of a strongly closed entity that cannot be perturbed by other entities and that cannot perturb many other entities. Between the indifference of Urulu to its proper name and the indifference of neutrinos to most other entities, there's a difference in degree rather than kind. While it is important to recognize that most inanimate objects cannot answer to their name (computers are quickly calling this generalization into question), there is no reason to treat culture as a special domain or distinct realm unlike material interactions. In both cases, the issue is one of how entities are selectively open to their environment.

The second consequence that follows from treating allopoietic objects in terms of self-referential system/environment distinctions that are only selectively open to their environment is that allopoietic objects cannot be treated as bundles of qualities. Qualities are results of how allopoietic objects are actualized by their perturbations. They are things that objects can do, but they do not define the proper being of objects which consists of powers. As I tried to show in my discussion of Bhaskar in the first chapter, objects can be “out of phase” with the events they're capable of producing. When situated in terms of qualities, this means that objects can exist, they can be there in the world, either in a dormant state where they produce no qualities of a particular sort, or in a state where, due to the intervention of other generative mechanisms or objects they produce exo-qualities that inhibit the production of particular qualities of which the object is capable.

The key point not to be missed is that the qualities of an object are variable. Every object, allopoietic or autopoietic, is capable of a variety of different local manifestations. And we can say that perhaps every object is capable of producing an infinite number of different properties. This is among the reasons that we cannot treat objects as bundles of qualities. Qualities are products of how allopoietic objects are perturbed, how those perturbations are transformed into information, and how that information selects system-states producing local manifestations.

The question that emerges here is that of why, if objects cannot be equated with their qualities, we have such a persistent tendency to reduce objects to their qualities. I think there are two basic reasons for this. The first has to do with the type of objects we are. Like all objects, we are operationally closed and relate to the world only through the distinctions that regulate our openness to the world. These distinctions, like all distinctions, have a marked and an unmarked space, such that the unmarked space becomes invisible or disappears. In the case of our perceptual world, one operative distinction seems to be the distinction between identity and change. Here identity functions as the marked state, while change functions as the unmarked state. If this schema plays such an important role in our experience of the world, then this is because, as Bergson observed long ago, our perception is geared towards action and our ability to act on other objects. Since action requires a more or less stable platform to take place, change and difference is thrown over into the unmarked side of the distinction governing our perception and cognition. When I go to grab my beloved coffee mug, I register it not as a series of variations or different local manifestations, but as a blue coffee mug. I register my mug in this way even when the lights are out and the mug is no longer blue. Here the blueness of the mug functions as a marker for returning to the mug. “Oh, there's my mug!”

However, while the manner in which we translate objects plays a role in our tendency to treat objects as bundles of qualities, there are object-centered reasons for this tendency as well. While objects are, in principle, independent of their relations, objects are only ever encountered in and among relations to other objects. Terrestrial existence is such that these relations are more or less stable and enduring. The consequence of this is that allopoietic objects tend to be perturbed by other objects in their environment in more or less constant ways. Insofar as objects are perturbed in more or less constant ways by other objects in their environment, they tend to have fairly stable and ongoing local manifestations. As a consequence, the volcanic powers objects have folded within them remain largely hidden from view.

I refer to networks of exo-relations like this as “regimes of attraction”. Regimes of attraction are networks of fairly stable exo-relations among objects that tend to produce stable and repetitive local manifestations among the objects within the regime of attraction. Within a regime of attraction, causal relations can be bi-directional or symmetrical or uni-directional or asymmetrical. Bi-directional causation is a circular relation in which two or more entities reciprocally perturb one another in response to each other. Like fireflies signaling to one another, one lightning bug lights up and another lights up in response, leading the first to light up again. Similarly, one object perturbs another, producing an act in the second object that in turn perturbs the first object that started the sequence. As a consequence of these sorts of relations, we get constant local manifestations. The moon’s gravity affects the earth and the earth's gravity affects the moon. Likewise, we can have uni-lateral or asymmetrical relations of perturbation that bring about a largely constant state in an object.

Fire is a particularly good example for illustrating the idea of regimes of attraction. In its terrestrial manifestation, fire behaves in relatively predictable ways. It leaps up towards the sky and is characterized by pointed tongues of flame that dance and oscillate. As a consequence, we are led to think of this sort of behavior (these qualities) as constituting the essence of fire. However, in outer space, fire behaves more like water, rolling over things in waves, expanding everywhere like liquid on the surface of a table. In its terrestrial manifestation, fire behaves this way because of the gravity of the earth. Here fire exists within a particular regime of attraction that leads to very specific local manifestations. When situated in different regimes of attraction, fire behaves in a very different way.

The concept of regimes of attraction is of central importance to onticology and has profound implications for how we think about epistemology or inquiry. The concept of regimes of attraction entails that it is not enough for inquiry to merely gaze at objects to “know” them, but rather that we must vary the environments of objects or their exo-relations to discover the powers hidden within objects. Knowledge of an object does not reside in a list of qualities possessed by objects, but rather in a diagram of the powers hidden within objects. However, in order to form a diagram of an object we have to vary the exo-relations of an object to determine that of which it is capable. And here, of course, the point is that knowledge is gained not by representing, but, as Aristotle suggested in a different context in the Nicomachean Ethics, by doing. In the case of Aristotle, this doing consists of repeated actions so as to produce habits or dispositions of action. In the case of other forms of knowledge, by contrast, this doing consists in acting upon objects to see what they do under these conditions.