Adopted Chinese Girls’ Character Strengths from Preschool to School Age: A Longitudinal Exploratory Study

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

In the current study, we used a strength-based approach to explore post-adoption character strengths from preschool age (Time 1; M = 4.9 years, SD = 0.56) to school age (Time 2; M = 6.8 years, SD = 0.55) in a sample of girls adopted from China (N = 162). These girls were adopted from Chinese orphanages at 15.1 months on average (SD = 5.2), with 87% under 24 months at the time of adoption. They lived in 157 adoptive homes in the U.S. or Canada. Qualitative data on these girls’ best attributes were collected from the same adoptive parents at both time points. Using the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues as a conceptual framework, data were coded to identify perceived character strengths, as well as their change and continuity from Time 1 to Time 2. The coded data revealed that the most frequently described character strengths at both time points were Love, Kindness, Humor, Zest, Social Intelligence, and Creativity. These results were similar to a previously reported US sample of non-adopted young children’s character strengths, except that Zest was more common among the current sample of adopted girls. Overall, the rank order of character strength prevalence over time was highly comparable (ρ = .94), although substantial changes occurred at the individual-level. Findings from this study have implications in promoting resilience in children with pre-adoption orphanage deprivation.

Keywords: adopted Chinese children, character strengths, longitudinal study, values in action classification, virtues

In an effort to understand human strength and resilience and promote positive individual traits across the lifespan, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) called for the study of strengths and virtues. Brainstorming among leading positive psychologists, analyzing themes from a multitude of sources on positive character and virtues, and empirical investigations were subsequently carried out to create a framework known as the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues. This served as a new common vocabulary for discussing good character (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). According to Peterson and Seligman (2004), the VIA includes 24 character strengths categorized under six more broadly defined virtues, which were considered core characteristics that have been valued by moral philosophers and religious thinkers.

The character strengths are positive individual traits, psychological processes or mechanisms that are the “distinguishable routes to displaying one or another of the virtues” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; p. 13). Character strengths and virtues as proposed by the VIA serve to scientifically identify aspects of one's good "character". Individuals will have different combinations of specific character strengths and virtues that make up the overall profile of their character. A number of studies have since established that these 24 universal character strengths manifest themselves across different cultures (e.g., Biswas-Diener, 2006; Dahlsgaard, Peterson, & Seligman, 2005; Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2006). However, most research involved adult samples (e.g., Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004; Shiman, Otake, Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2006), with fewer studies focusing on the character strengths of youth (e.g., Park & Peterson, 2006a), and even less on young children (Park & Peterson, 2006b). Understanding the early development of character strength and factors that influence its development may have implications for fostering resilience, especially among children who might be at-risk for suboptimal development due to unfavorable earlier experiences (e.g., orphanage care). The current study explored the change and continuity of character strengths and virtues among girls who were adopted from China by families in the U.S. or Canada. These girls had previously lived in Chinese orphanages for a period of time. We applied the VIA framework to help identify the adopted Chinese girls’ character strengths and virtues development from preschool to school age. Our exploratory inquiry aimed to address three questions:

- What character strengths do parents report about their adopted Chinese children when their children are at preschool-age and early school-age?

- To what extent do adopted Chinese children’s character strengths change from preschool-age to early school-age?

- What is the relationship between parent, child, and/or family variables and the adopted Chinese children’s character strengths at preschool age and early school age?

Character Strengths in Children

The development of Values in Action (VIA) Classification has led to the identification of children’s character strengths. For instance, Park and Peterson (2006b) found that for children 3-9 years of age, the top 5 character strengths were Love, Creativity, Humor, Curiosity and Kindness. They also reported that for 10-17 year olds, the top 5 character strengths were Love, Creativity, Teamwork, Gratitude, and Humor (e.g., Park & Peterson, 2006a). For children under 10 years of age, researchers have usually relied on parent reports to obtain data on the children’s character strengths. As can been seen from the two studies described above, there are both differences and similarities in character strength between children in the two age groups. This might reflect both change and continuity that are typical in childhood development (Rutter & Rutter, 1993). To gain a better understanding of developmental differences and similarities over time, however, Park and Peterson (2006a; 2006b) called for studies to closely examine the development of character strengths longitudinally as a means of addressing the limitations of extant cross-sectional results.

Adjustment of Internationally Adopted Children

Despite early experiences of abandonment and varying levels of social-emotional, cognitive, and physical deprivation from orphanage care, children who were adopted internationally from different countries into Western countries appear to be relatively well-adjusted as compared to non-adopted children (see the meta-analysis by Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005). However, more severe pre-adoption deprivation (e.g., abuse in the orphanage) has been linked to less optimal post-adoption functioning in internationally adopted (IA) children (Rutter et al., 2007). As a longer period of orphanage living for a child is usually tied to an older age at adoption, in most studies age at adoption was negatively correlated with later functioning (e.g., Gunnar, van Dulmen, & the IAPT, 2007). Heterogeneity in IA children’s post-adoption adjustment, however, has also been widely documented. According to a meta-analysis of 100 studies, Juffer and van Ijzendoorn (2005) concluded that girls tend to fare better than boys. Children adopted from Asian countries (e.g., Korea) also tend to outperform IA children from other countries (e.g., Russia) in post-adoption behavioral adjustment (e.g., Merz & McCall, 2010; Odenstad, Hjern, Lindblad, Rasmussen, Vinnerljung, & Dalen, 2008) and school performance (van IJzendoorn, Juffer, & Klein Poelhuis, 2005).

Children adopted from China have several unique characteristics, including the fact that the overwhelming majority of them are girls, due to China’s one-child-per-family population control policy and Chinese culture’s male preference, and most children are born to married couples in rural China where smoking, drinking and drug use is extremely rare among women (Tan & Marfo, 2006). As a result, most of the Chinese children available for adoption do not have pre-natal drug/alcohol exposure. These characteristics may contribute to their favorable post-adoption behavioral and academic development (e.g., Tan & Marfo, 2006; Tan, 2009). Parents with preschool-age adopted Chinese girls reported that their children’s difficulties with such issues as attachment, sleep, and peer-relations were most concerning (Tan, 2010). Nevertheless, Tan and Marfo (2006) found that their sample of 695 children (517 aged between 1.5-5 years and 178 aged between 6-11 years) adopted from China had similar or lower levels of internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems (measured with the Child Behavior Checklist) when compared to U.S. normative groups. Developmentally, however, similar to non-adopted girls, there is some evidence of change in adjustment over time, with a significant increase of internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety) from preschool to school ages (Tan, 2011). Another unique finding related to this population is that Chinese girls’ age at adoption does not appear to be significantly related to behavioral adjustment, mainly due to that most of the children were adopted at a young age (e.g., Rojewski, Shapiro, & Shapiro, 2000; Tan & Marfo, 2006).

Despite that adoption itself has been considered a form of intervention (van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2006), rarely have any existing studies taken a strength-based approach to help identify sources of resilience in internationally adopted children. Instead, existing studies mostly used a deficit-based approach to examining the problematic development of IA children with early orphanage rearing (see meta-analysis by Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005). One exception was a strength-based study by Pearlmutter, Ryan, Johnson, and Groza (2008) who found children (with a mean age of 10 years old) adopted from Romania to have above average intrapersonal and affective strength. In view of the limited number of studies that have explored the character strengths of the adopted children, there is a need for a strength-based approach in studying post-adoption development. Such research might yield useful insights to help foster resilience in adopted children. In the current longitudinal analysis, we focus on the strengths and virtues of a sample of girls adopted from China at 4-5 years of age and at 6-7 years.

Method

Sample

Internet discussion groups have become a popular forum for adoptive families to communicate on all aspects of adoption-related topics. In this study, participants were recruited through these discussion groups, as well as major adoption agencies. In early 2005, through one group moderator, a recruitment letter, with an introduction of the research project by this moderator, was posted on the message board of the internet moderators’ group. The other moderators were asked to disseminate the recruitment letter to members of their respective groups. At the same time, the recruitment letter, together with the same introduction, was mailed to the directors of 10 adoption agencies in the U.S. (e.g., Chinese Children’s Adoption International, China Adoption With Love, Inc., and Alliance for Children).

Overall, the study was endorsed by 120 internet discussion groups and 6 adoption agencies. The groups included organizations associated with Chinese adoptions in general (e.g., Families with Children from China; Raising China Children), as well as groups with a more specific focus. The latter included (a) groups for families of children adopted from certain regions of China and (b) groups organized around specific developmental issues and topics, such as attachment, special needs, identity, and general post-adoption adjustment. As most families belong to more than one organization, some received information about the study simultaneously from multiple sources. Parents interested in participating in the study contacted the research program directly with information about the number of children they had adopted from China, number of biological children, age of each child, and a regular mailing address.

A total of 1,001 families from the U.S. and 91 families from other countries (e.g., Canada, Australia, and the U.K.) requested surveys. The U.S. families were from 49 states. A packet that included study instructions, consent form, demographic survey, survey on the adopted child’s pre-adoption experience, and the Child Behavior Checklist for 1.5-5 years (CBCL/1.5-5) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) or CBCL for 6-18 years (CBCL/6-18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was mailed to the adoptive parents via regular mail within two days of receiving the parents’ request. An email confirming the mailing of surveys was sent to the adoptive parents within a week thereafter. For the returned surveys, an email thanking the family was sent and for surveys that were not returned within three weeks, an email reminder was sent to the parents. A total of 852 families (about 78.1%) returned the surveys. The total number of children within these families was 1,193, of whom 1,122 (94%) were adopted from China; the rest were the biological children of the adoptive families.

Two years later in the spring of 2007 (Time 2), 780 of the 853 families (for 72 families, contact information was no longer valid) were successfully contacted for the second phase of the study (one family declined to participate without explanation). Using a similar method from Time 1, a packet containing the CBCL was sent to the 780 adoptive families. Data from 675 families (86.5%) with 1,111 children were obtained. These families had 882 adopted Chinese children and the rest were the biological children of the adoptive parents.

Data Source for the Current Analysis

In both phases of the study, the adoptive mothers were asked to “Please describe the best things about your child”. Their responses were used to identify character strengths of the adopted Chinese children. Our data gathering approach was similar to the study of young children’s personality, in which parents responded to one open-ended question about their young children (Kohnstamm, Halverson, Mervield, & Havill, 1998). Additionally, Glascoe and Dworkin (1995) suggested that parents are often the most reliable source of their children’s behaviors. In a recent study on children adopted from China, Tan (2010) successfully identified behaviors that concerned the adoptive parents most using a similar approach. Equally importantly, our method closely resembles the method used in the only other study of the VIA Classification of Character Strengths among young children by Park and Peterson (2006b).

Demographic variables were gathered using a child and family background survey at Time 1. Parents were asked to report on current marital status, presence of other children living in the home, household income, parents’ age, child’s date of birth, age at adoption, and date of data collection. Children’s chronological ages in months were calculated from their date of birth and date of data collection. They were used as predictors for the logistic regression analyses in the current analysis.

Selecting Criterion for Children in the Current Analysis

In response to the need for longitudinal studies on young children’s character strength development, we chose to study a sub-sample of adopted Chinese girls who were 4-5 years of age at Time 1 and were 6-7 years at Time 2. We were interested in the transition from preschool to school age because developmentally this is a period for adopted children to start understanding the meaning and implications of adoption (Brodzinsky, Singer, & Braff, 1984), and socially this is also a period during which children’s social context expands significantly (Selman, 1980).

From the dataset, we identified 184 children who met the age criterion. After excluding seven boys and 10 girls with missing Time 2 data, 162 girls from 157 families (i.e., five parents had two girls) aged 4-5 years (i.e., preschool ages) and 6-7 years of age (i.e., early school ages) at Time 2 were included for this analysis. The attrition appeared to be random as there was no difference in any area between the children who dropped out and those who remained. At Time 1, they were 4.9 years (SD = 0.56) on average and were 6.8 years (SD = 0.55) on average at Time 2. These girls’ average age at adoption was 15.1 months (SD= 5.2, Range= 7-55). The adoptive mothers’ average age at Time 1 was 45.2 years (SD = 5.2). Over 90% of the mothers completed at least college, and nearly 60% had a masters degree or higher. The adoptive families’ median annual household income in 2004 was $80,000 to $89,999, with only 10% of families making less than $50,000 per year. Sixty-four percent of mothers were married or living with a spouse or partner, and 69% of children had other adoptive siblings in the home.

Data Coding Procedures

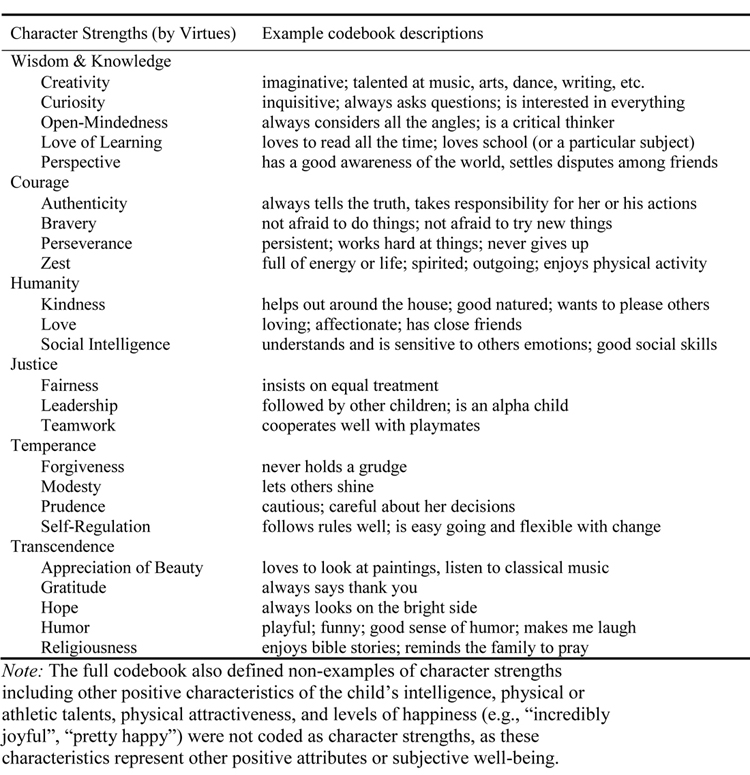

Paralleling the coding procedures used in Park and Peterson’s (2006b), we developed a codebook based on the VIA Classification’s 24 character strengths. We adopted the age-appropriate manifestations and behavioral indicators described in Park and Peterson’s study, along with the description of each strength (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and additional relevant example descriptions based on initial readings of the data. An abbreviated version of the codebook is presented in Table 1.

While conventionally two raters are involved in coding qualitative data, as was the case in Park and Peterson’s content analysis, a more stringent approach with three raters (i.e., first and second author, and an advanced graduate student) was used for the current analysis to help further validate the themes emerged from the data and ease the limitation of having relatively brief responses.

During the training session, the first author provided didactic explanations of each individual character strength code as well as group discussions to clarify meanings. All three raters then coded 15 cases for practice, followed by discussing each rater’s line of reasoning to build initial consensus. This process facilitated refining the codes and establishing reliability, particularly for the responses that were somewhat ambiguous. For example, one mother described her child as ‘charming,’ and this resulted in discrepant independent coding. Because ‘charming’ is associated with pleasing others, the codes of Kindness and Social-Intelligence were discussed as possible codes. Through group discussion, it was agreed upon that “charming” implied the ability of knowing how to please others in different situations and that charming behaviors can be displayed for purposes other than trying to be kind; thus, ‘charming’ was considered a descriptor of Social Intelligence.

Following this training session, the three raters independently coded 50 randomly selected cases. A total of 181 codes (M = 3.62 per child) were endorsed by at least one rater. Agreement on each code between any two of the three raters was fairly high (i.e., 75.1%), although the three-rater agreements were understandably lower (i.e., 58.0%). Instances in which there were discrepancies across raters were then discussed, similar to the initial try-out discussions described above, which refined the codes. The raters discussed the codes until consensus across the three raters was achieved.

Character strength codes were then grouped into the six virtues from the VIA Classification. This was done in an effort to reduce the likelihood for Type I errors during statistical analyses as it resulted in fewer numbers of statistical tests to be conducted. Specifically, character strengths data were grouped into the VIA Classification’s core virtues based on the presence or absence of any one or more character strengths associated with a virtue. Thus, similar to the character strengths, virtues were dichotomous variables, not summative scores. Specifically, the 24 character strengths were grouped in accordance with the VIA Classification’s six virtues-Wisdom and Knowledge, Courage, Humanity, Justice, Temperance, and Transcendence (see Table 1 or Table 3 for information on which character strengths comprise each of these virtues). Character strengths data were re-coded for each virtue based on the presence or absence of any one or more character strengths associated with a virtue. When none of the character strengths within a virtue category was coded for a child, the virtue was coded 0 (not present), but when one or more character strengths within a virtue category were coded for a child, the virtue category was coded a 1 (present). For example, if a child received codes for Kindness and Love, that child received a code of 1 for Humanity. A child who received a code for Love only was given a code of 1 for Humanity. Similar to the character strengths, virtues became dichotomous variables, not summative scores.

Data Analysis Plan

Frequency counts of the coded character strengths were used to determine the prevalence rates of each character strength in the sample at Time 1 and Time 2. Character strength prevalence rates at Time 1 and Time 2 were each rank ordered from lowest (1) to highest (24) and the Spearman ρ correlation analysis was used to compare the rank order profile of Time 1 to Time 2. Nonparametric statistical testing was also used to test for significant differences between prevalence rates of character strengths over time from preschool (Time 1) to school age (Time 2). Specifically, the McNemar test of marginal homogeneity was used since this test is appropriate for nominal data with matched pairs of subjects. The degree of similarity between Time 1 and Time 2 for each character strength was also analyzed through correlation analyses. Recognizing that 24 tests for the character strengths were conducted, more stringent significance levels were examined, including the use of Bonferroni corrections (.05 divided by 24). Each of the analyses described above were then also calculated for virtues.

To further reduce the likelihood of Type I errors, only the 6 broader virtues were used for further analyses to determine significant predictive relationships with additional child, parent, and/or family variables. Logistic regression rather than multiple regression was used with the virtues due to the fact that dichotomous criterion variables (i.e. presence or absence of virtues) were analyzed rather than continuous variables. To reflect several child, parent, and family variables, child’s age (at Time 1), age at adoption, household income, single or two parent household, mothers’ age, and presence or absence siblings served as the predictor variables. As a check for multicolinearity among these variables, inter-item correlations among these variables at Time 1 were found to be low, ranging from -.21 to .34, indicating sufficient independence for logistic regression.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

At Time 1, parent descriptions of the child’s strengths ranged from 2 words (e.g., “affectionate, caring”) to 101 words (M = 21.2). After each description was coded, the average number of character strengths per child was 2.93 (SD = 1.62, Range = 0-8 strengths). At Time 2, the parent descriptions range was from 3 to 96 words (M = 17.7). At Time 2, the average number of character strengths for a child was 2.94 (SD = 1.27; Range = 1-6).

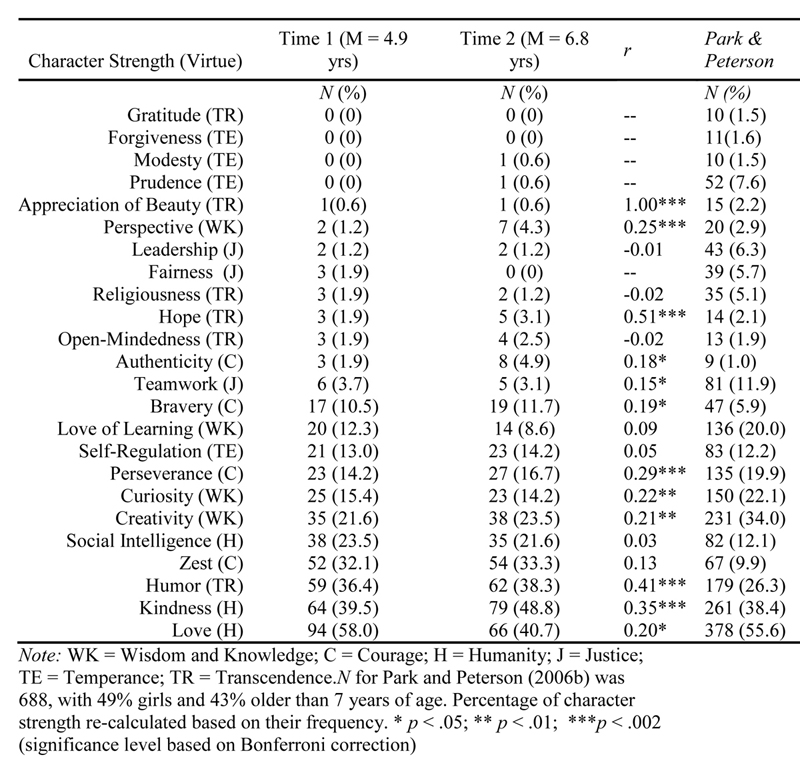

Table 2 summarizes the frequency of character strengths at Time 1 and Time 2, with the character strengths organized in ascending order based on the prevalence of the character strengths at Time 1. Considerable variability existed in the prevalence of each character strength in the sample. Thirteen of the 24 character strengths (e.g., Gratitude) at both times were found in less than 5% of the children. The remaining 11 character strengths ranged in prevalence from 10.5% (Bravery) to 58.0% (Love) at Time 1 and 8.6% (Love of Learning) to 48.8% (Kindness) at Time 2.

Although our sample includes only girls who were younger than Park and Peterson’s (2006b) sample, we included in the table the results of Park and Peterson for a rough comparison. Both similarities and differences were noted. Nonetheless, the considerable variability in frequencies at which the more prevalent character strengths were described makes the similarities and differences between samples in the rank ordering and actual frequency of character strengths more interpretable than within the rarely described character strengths that varied much less. The top two strengths at both time points, Love and Kindness, were the top two strengths among those reported in Park and Peterson’s sample. Humor was the third and fourth most prevalent character strength among the current sample and Park and Peterson’s sample, respectively. Character strengths of the Wisdom and Knowledge virtue (i.e., Love of Learning, Curiosity, and Creativity) were prevalent at lower rates among Chinese adoptees when compared to the non-adopted children, though the order of prevalence within both samples was the same (i.e., Love of Learning was less frequent than Curiosity, which was less frequent than Creativity). The most dramatic difference appeared with respect to Zest and Social Intelligence, which were much more prevalent among the adopted sample (i.e., 32.1% and 23.5% at Time 1, respectively) compared to Park and Peterson’s sample (i.e., 9.9% and 12.1%, respectively). Zest and Social Intelligence were among the top five most prevalent character strengths at both time points among the adopted sample, while only the ninth and eleventh most prevalent among Park and Peterson’s sample.

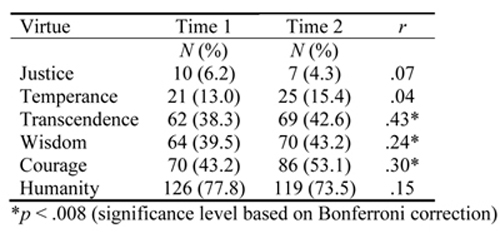

As seen in Table 3, even greater variability existed in the prevalence of each virtue in the sample, ranging from 4.3% (Justice, Time 2) to 77.8% (Humanity, Time 1). We did not include the results from Park and Peterson (2006b) in the table since they did not provide the statistics in their study.

Change and Continuity in Prevalence from Preschool to School Age

When comparing the ranked character strengths from lowest (1) to highest (24) from both time points, the Spearman ρ correlation was .94 (p < .001), indicating very high similarity in the sample’s character strength profile from Time 1 to Time 2.

Further analysis through McNemar tests of homogeneity showed that Love was the only character strength with a significant change (< .002) in prevalence over time. It decreased from being represented among 58.0 % of children at Time 1 to 40.7% of children at Time 2, χ2 (1, N = 162) = 10.72, p < .001. An increase in Kindness from 39.5% at Time 1 to 48.8% at Time 2 also approach the less stringent statistical significance (not applying a Bonferroni correction), χ 2(1, N = 162) = 3.70, p = .054. In terms of virtues, none were significant using a Bonferroni correction significance level (p < .008). Using the less stringent significance level, Courage was the only virtue that increased in prevalence from 43.2% of children at Time 1 to 53.1% of children at Time 2, χ2(1, N = 162) = 3.88, p < .05.

To determine if the same character strengths were described for the same children at both time points, we focused on the 11 character strengths that occurred within 10% or more of the sample (as there is too little variability in the rarely described character strengths).

As shown in Table 2, Kindness, Humor, and Perseverance were the only strengths that were correlated significantly when the most stringent p value was applied. With less stringent p values, there were five character strengths with moderately strong correlations (r = .19 to .29). The correlations between time points for Kindness and Humor were fairly strong (r = .35 and .41, respectively). More specifically, 64% of children with Humor as character strength at Time 1 continued to be described similarly at Time 2, and 70% of children with Kindness at Time 1 continued to be described similarly at Time 2. These results suggest both change and continuity in the children’s character strength development.

Child, Parent, and Family Variables Related to Virtues

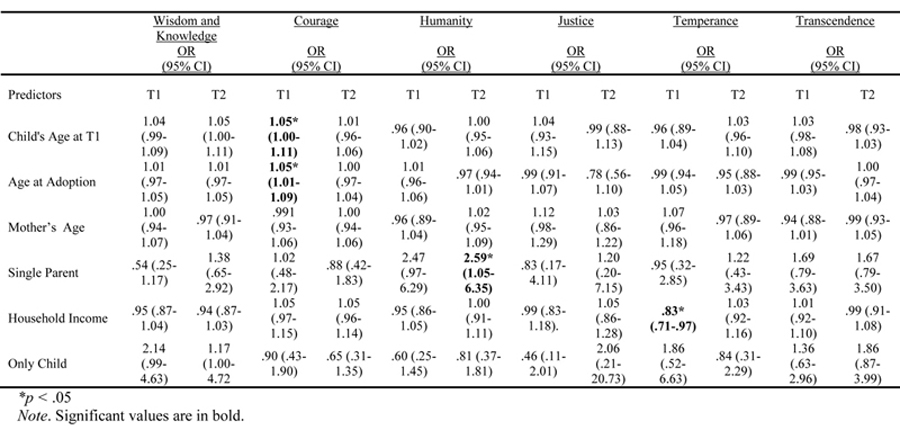

To test relationships between the (presence or absence of) virtues and child, parent, and family predictors, logistic regressions for Time 1 and Time 2 were performed with several predictors, including child’s age, age at adoption, family income, single or two parent household, mother’s age, and whether the child was the only child in the household.

As shown in Table 4, most of the variables did not have a significant impact on the odds of the virtues being present with a few exceptions. For instance, during preschool years (Time 1), the odds were higher for older children as well as children who were older at the time of adoption to show character strengths that indicated Courage. Interestingly, at Time 2, children from single parents household were about 3 times more likely than their peers from two-parent households to show character strengths that were indicative of Humanity.

Discussion

While deficit-based approaches have provided important insights in the adopted children’s post-adoption problematic adjustment, there is a need for strength-based approach in understanding adopted children’s post-adoption resilience and flourishing. To the best of our knowledge, the current study serves as the first longitudinal study of the VIA Classification among young children and the second study on internationally adopted children to primarily assess a broad spectrum of strengths.

Our study showed that at both times, the adopted Chinese girls were similar to the non-adopted children in the study by Park and Peterson (2006b) in average number of identified strengths. The adopted Chinese girls at both times also share a similar character strength profile to the children from the general population in Park and Peterson’s (2006b) study. For instance, among the 13 infrequent character strengths in our sample, 12 overlap with what was reported in Park and Peterson’s sample. At the same time, 10 of the more frequent strengths overlap between the two studies, suggesting that the adopted Chinese children were similar to the non-adopted children. Given that the adopted Chinese girls had spent some time in the orphanages, this finding is impressive and highlights the resilience of child development. Future research is needed to tap into specific mechanisms within the child and adoptive family that foster the adopted children’s resilience from pre-adoption orphanage deprivation.

However, there are indeed some differences in the prevalence of specific character strength. For instance, over 30% of the adopted Chinese girls were reported to have Zest, as compared to under 10% of the sample in the study by Park and Peterson (2006b). In an earlier study by Tan and Marfo (2006), they had speculated that a selection process might have been used by the Chinese child welfare authorities to identify babies that were mostly likely to thrive in adoptive environment. Children who exhibited characteristics that might signal Zest may have been deemed most suitable for international adoption by the Chinese authorities. Of course, more studies are warranted to help determine whether the differences might have resulted from differences in the sample’s age and gender differences or differences in earlier psychosocial experiences between our study and theirs.

Change and Continuity in Character Strengths

The longitudinal design provides good insights into both change and continuity of the adopted Chinese girls’ character strength and virtue from preschool ages to early school-ages. Results showed that most character strengths and virtues remained stable over a two-year span. There was, however, a significant decrease of Love and a significant increase of Courage. In terms of Love, it should be noted that while it decreased in frequency, it was still the second most prevalent character strength when the children were in school ages. One interpretation for this decrease could be related to parents’ greater sensitivity to establishing a loving relationship with an adopted child early in their post-adoption lives. A concern for the development of an attachment disorder, characterized as an inability to give or receive love and affection (e.g., Levy & Orlans, 2000), might initially lead adoptive parents to be particularly vigilant about their child’s expression of love. As children get older, that heightened vigilance may fade. The decrease in Love could also make sense from a developmental perspective, as the expression of love through affection for a caregiver is something that can be seen from infancy.

With increasing age and cognitive maturation, other developmentally salient strengths (e.g., learning in school) might become the focus of the adoptive parents’ descriptions. Courage, a virtue comprised of Authenticity, Bravery, Perseverance, and Zest and described as an “exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of opposition, either external or internal” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004, p. 199), appears to become more prevalent over the course of the transition from preschool to school ages. Given that these children were racially different from their parents, future research on their children’s ethnic identity formation might help shed some light into whether “Americanization” plays a role. On the other hand, virtues of Justice, Temperance, and Transcendence were endorsed at low rates across this transition, indicating they would not increase significantly until older ages.

At the individual level, some character strengths were more consistent over time than others. Humor and Kindness were the most consistent and highly correlated over time (of the 11 more prevalent strengths for which the frequency was high enough to be meaningfully interpreted), indicating a higher likelihood that humorous or kind girls in their preschool years will continue to exhibit those attributes in their early elementary school years. Most of the character strengths were either not significantly correlated or had weak positive correlations from Time 1 to Time 2, which is interesting given that the rank ordered character strength profile for the sample was so highly correlated. One speculation is that while there appear to be clear distinctions between the types of character strengths that are displayed frequently during this age range, individual children for the most part have not yet developed stable signature strengths at this young age. More research is needed to explore the malleability of one’s character strengths throughout childhood.

Another key variable to consider in adoption research is the age at which the child is adopted. Among Romanian adoptees, children adopted after 24 months were at greater risk for higher levels of problem behaviors (Meese, 2005) and lower levels of behavioral and emotional strengths (Pearlmutter et al., 2008). Nevertheless, age at adoption in this sample was only predictive for Courage, with only a relatively trivial increase in likelihood of occurrence. This finding of a lack of significant or strong associations with age at adoption was consistent with existing research (e.g., Tan & Marfo, 2006). This finding may have been influenced by the relatively young ages at adoption. Only 13% of the sample was adopted at 24 months or older.

Finally, children in single–mother households appeared to score higher on the virtue of Humanity at Time 2 than their peers in dual-parent households. According to Groze and Rosenthal (1991), adopted children may benefit from single-parent families’ relatively simple relationship structure. More research is needed to understand how family structure affects adopted children’s character strength development.

Limitations

Our study focused on trans-racially adopted Chinese girls. In the U.S., the stereotypes associated with children of Asian descent (e.g., being model minorities) has been frequently reported (e.g., Lee, 1996). Thus, our sample’s gender and racial background might have played a role in our results. It is beyond the scope of the current study to determine to what extent the very fact that these children were Chinese girls might influence the adoptive parenting, yet this issue deserves attention in future research. The results from our study might not generalize to trans-racial adoptees from a different racial background or from a domestic adoption, in-racial adoptees, or male adoptees.

Using one open-end question to gather data was a notable limitation of our study. However, similar approaches have been successfully used in many studies (e.g., Park & Peterson, 2006a, 2006b). Nevertheless, research using a more systematic approach could help learn more about the development of character strength in young children and help validate the method used in the current study. Potential biases associated with non-random, convenience sampling procedures should also be considered when evaluating the findings of the current study, despite a 78% response rate at Time 1 and 87% response rate at Time 2. These considerably high response rates for mail-based survey research may have helped mitigate biasing effects of self-selection.

Implications

Overall our study showed that the character strength profile among the current sample of adoptees remained relatively stable after transitioning from preschool age to school ages, and the profile was similar to that of a previously reported US sample of non-adopted young children. Based on this longitudinal data and comparison to the US non-adopted sample, certain character strengths appear to be ones that develop at younger ages (e.g., Love, Kindness, Humor, Zest, Social Intelligence), while others do not appear to manifest at young ages (e.g., Gratitude, Forgiveness, Modesty, Prudence).

Transitioning to school can present challenges to both adopted and non-adopted children and their parents. Examining positive characteristics of internationally adopted Chinese girls during the transition can broaden our understanding of their post-adoption development. The similarities help support some generalizable understanding of character development in young children. The differences, however, could provide some targets for building upon unique strengths. For instance, given their noticeably high prevalence of Zest and Social Intelligence, the adopted Chinese girls may benefit from educational activities that tap into these strengths.

Conclusion

China has been the leading country of the US international adoptions for a decade (US Department of State, 2011). Professionals involved with children and families will inevitably encounter many of these adoptees in their respective fields. It could prove useful to understand which strengths to expect based on a child’s developmental stage and capitalizing on their unique strengths in any efforts aimed at fostering their resilience and ability to thrive.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Biswas-Diener, R. (2006). From the equator to the North Pole: A study of Character strengths. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 293-310.

Brodzinsky, D. M., Singer, L. M., & Braff, A. M (1984). Children’s understanding of adoption. Child Development, 55, 859-878.

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 9, 209–213.

Glascoe, F. P., & Dworkin, P. H. (1995). The role of parents in the detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatrics, 95, 829-836.

Groze, V. K., & Rosenthal, J. A. (1991). Single parents and their adopted children: A psychosocial analysis. Families in Society, 72 (2), 67-77.

Gunnar, M. G., Van Dulmen, M. H. M., & The International Adoption Project Team. (2007). Behavior problems in postinstitutionalized internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 129-148.

Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), 293, 2501-2515.

Kohnstamm, G., Halverson, C., Mervielde, I., & Havill, V. (1998). Parental descriptions of child personality: Developmental antecedents of the Big Five? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lee, S. J. (1996). Unraveling the "Model Minority" Stereotypes: Listening to Asian American Youth. Teachers College Press, New York.

Levy, T., & Orlans, M. (2000). Attachment disorder as an antecedent to violence and antisocial patterns in children. In T. Levy (Ed.), Handbook of attachment interventions (pp. 1–26). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Meese, R. L. (2005). A few new children: Postinstitutionalized children of intercountry adoption. Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 157-167.

Odenstad, A., Hjern, A., Lindblad, F., Rasmussen, F., Vinnerljung, B., & Dalen, M. (2008). Does age at adoption and geographic origin matter? A national cohort study of cognitive test performance in adult inter-country adoptees. Psychological Medicine, 38, 1803-1814.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006a). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 891-909.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006b). Character strengths and happiness among young children: Content analysis of parental descriptions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 323-341.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(5), 603-619.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Character strengths in fifty-four nations and the fifty US states. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 118-129.

Pearlmutter, S., Ryan, S. D., Johnson, L.B., & Groza, V. (2008). Romanian adoptees and pre-adoptive care: A strengths perspective. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 25(2), 139-156.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rojewski, J. W., Shapiro, M. S., & Shapiro, M. (2000). Parental assessment of behavior in Chinese adoptees during early childhood. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 31(1), 79-96.

Rutter, M., Beckett, C., Castle, J., Colvert, E., Kreppner, J., Mehta, M., et al. (2007). Effects of profound early institutional deprivation: An overview of findings from a UK longitudinal study of Romanian adoptees. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4, 332-350.

Selman, R. L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. New York: Academic Press.

Shimai, S., Otake, K., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Convergence of character strengths in American and Japanese young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 311-322.

Tan, T. X., & Marfo, K. (2006). Parental ratings of behavioral adjustment in two samples of adopted Chinese girls: Age-related versus socio-emotional correlates and predictors. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 14-30.

Tan, T. X. (2009). School-age adopted Chinese girls’ behavioral adjustment, academic performance, and social skills: Longitudinal results. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(2), 244-251.

Tan, T. X. (2010). Preschool-age adopted Chinese girls’ behaviors that were most concerning to their mothers. Adoption Quarterly, 13(1), 34-49.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2006). The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 2006: Adoption as intervention: Meta-analytic evidence for massive catch-up and plasticity in physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47, 1228–1245. van IJzendoorn, M. H., Juffer, F., & Klein Poelhuis, S. W. (2005). Adoption and cognitive development: A meta-analytic comparison of adopted and nonadopted children’s IQ and school performance. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 301–316.