Social Factors Predicting Women’s Consideration of Adoption

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This study examines predictors of considering adoption in a sample of 579 Midwestern women. While 40% considered adoption, only 20% took further steps to adopt. Multinomial regression was used to examine factors that predict considering adoption and taking further steps to adopt. Women’s attitudes about parenting, experience with infertility, race/ethnicity, and experience with fostering or other long-term informal child care were significant predictors of considering adoption and taking steps to adopt. Additionally, more religious women were more likely to consider adoption, but not more likely to take steps to adopt.

Keywords: adoption, adoption seeking, predictors

Although there is a great deal of discourse about adoption in the popular press (Margolis, Elkin, Nemtsova, Polier, & Lee, 2008; Katz, 2008), few empirical research studies have examined the specific predictors of adopting. It is important to note that existing research indicates a significant disconnect between people’s favorable attitudes toward adoption and actually adopting a child. Studies indicate that about 90% of people have a very or somewhat favorable attitude toward adoption (Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 1997; Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002). Additionally, over 80% of respondents also expressed agreement that parenting adoptive children can be as satisfying or more satisfying than parenting biological children (Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002), and anywhere from 25 to 40% of people say they have considered adoption themselves (Chandra, Abma, Maza, & Bachrach, 1999). However, this is in contrast to recent data showing that, among American women aged 18-44, only 1.1% had ever adopted a child and only 1.6% were currently seeking to adopt (Jones, 2008). Further, only about 2.5% of children under the age of 18 in the United States are adopted (Kreider, 2003). Consequently, while adoption is viewed as favorable by nearly all Americans, adopting a child continues to be a rather rare occurrence, experienced by relatively few individuals.

A better understanding of the influences on adoption-seeking attitudes and behaviors is especially important considering the large number of children in need of adoptive families and the importance of permanent familial relationships on healthy child development. In the United States, children may be adopted through the foster care system, privately from within the United States or internationally, or through kinship adoptions, making the actual number of children in need of adoption difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, merely taking into account the number of children in foster care who are waiting to be adopted provides ample evidence for the significant continued need for adoptive placements for children. According to recent data, an estimated 408,425 children are in foster care in the United States, and more than 107,000 of them are waiting to be adopted ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011).

In light of the apparent disconnect between attitudes and behavior regarding adoption, and in response to the number of children waiting to be adopted in the United States and elsewhere, it is important to understand the factors that affect potential adoptive parents’ consideration of adoption as well as those that influence them to move from merely considering adoption to actively pursuing the adoption of a child. A more thorough understanding of these processes is necessary to reduce barriers to adoption, and to increase the availability of adoptive families for children.

In this study, we examine factors that predict consideration of adoption by comparing three groups of women: those who have never considered adoption, those who have considered adoption but have not taken any steps beyond considering it, and those who have considered adoption and have taken steps in the adoption process ranging from talking with an adoption agency to adopting a child. Data are from a representative probability sample of women between the ages of 25 and 50 who reside in the Midwest. Previous research suggests women are more likely to consider adoption than are men (e.g. Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002). Factors examined as predictors of women’s considering and taking steps toward adopting include demographic, social, and attitudinal variables. The variables examined include age, race, marital status, income, religiosity, having given birth to a child, having experienced fertility problems, attitudes toward assisted reproductive technologies, the importance placed on parenting, whether the respondent intends to have another child, whether they have formally or informally cared for another person’s child, and whether they believe adoptive parenting is as potentially satisfying as biological parenting. A better understanding of the factors that predict or motivate adoption seeking in women can help to further explain the relationship between attitudes and behavior regarding adoption.

Attitudes Toward Adoption

Overall, research has shown that an overwhelming majority of people approve of adoption. The National Adoption Attitudes Survey indicates that 94% of Americans have a very or somewhat favorable view of adoption, and 63% have a very favorable view (Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002). The findings also show that compared to those surveyed in 1997 (Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 1997), respondents in 2002 were more likely to have a favorable view of adoption. Similar findings have been identified in studies focusing on select samples or specific types of adoption. Hollingsworth (2000a) found that 71% of people randomly selected to participate in a telephone survey approved of transracial adoption. Factors explaining approval included age, race, marital status, employment status, education, and political party affiliation. A study of college students’ attitudes also found very positive attitudes regarding adoption (Whatley, Jahangardi, Ross, & Knox, 2003). Over 90% of respondents indicated they would be willing to adopt a child if they could not have a biological child of their own.

Research regarding adoption also includes studies that examine attitudes toward placing children for adoption. For example, Daly (1994) found mixed support for adoption in a sample of 175 high school students. Although few of the adolescents said they definitely would make an adoption plan if they or their partner became pregnant, a much larger percentage indicated if a friend would get pregnant, that she should resolve the pregnancy by placing the baby for adoption. These views mirror the general societal attitude that there is a clear separation between what is desirable for others and what is desirable for oneself. As stated by Creedy (2001), it appears that both in terms of considering the adoption of a child and of considering relinquishing a child for adoption, “Adoption is at once second best and the right thing to do – for someone else” (p. 88).

In summary, there is an abundance of evidence indicating Americans’ favorable attitudes toward and acceptance of adoption. Unfortunately, there is also evidence that these attitudes are not necessarily consistent with actual behavior. In a review of the literature, Fisher (2003) reports that while Americans’ self-reported attitudes regarding adoption have become increasingly positive over the past few decades, actual adoptions, especially by nonrelatives, have declined considerably. Consequently, it seems that “adoption is a possibility that is often considered, but seldom chosen” (Fisher, 2003, p. 353).

Considering Adoption

It is important to understand the factors affecting individuals’ actual consideration of adoption as well as who ultimately completes the adoption process. Research by the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute (2002) focused on a random telephone sample of 1,416 respondents with an oversample of Blacks and Hispanics. Findings showed that about four in ten respondents had very seriously or somewhat seriously considered adopting a child at some point in their lives. Race, sex, age, and marital status were found to be significant predictors of who considers adoption. Hispanic respondents were more likely to say they had considered adoption than were Black or White respondents. Women were significantly more likely than men to report they had considered adoption and respondents who were less than 24 years of age or older than 65 were somewhat less likely to have considered adoption than were respondents in the middle age range. As expected, married respondents were more likely to have considered adoption than were never married, divorced, separated or widowed respondents. Education and income were not found to be significant predictors of consideration of adoption in this sample. As stated above, this study found that, overall, four in ten Americans have considered adoption at some point. However, research indicates that only about 1 in 50 women have actually ever applied to an adoption agency (Freundlich, 1998).

Bachrach, London, and Maza (1991) examined adoption seeking with structural and demographic variables in a national probability sample of 15 to 44 year olds. At the time of their study, the researchers estimated that about 2 million women of reproductive age had ever sought to adopt and about 200,000 were currently seeking to adopt. Adoption seeking was defined as “contact with an adoption agency or a lawyer” (p. 705). Factors shown to explain seeking to adopt for White respondents included infertility, experiencing child death or being childless, desiring more children than a woman expects to give birth to, being older, and being married. Religiosity (defined as religious participation at age 14) was not significantly related to adoption seeking nor was the respondent’s educational attainment. The researchers reported that it was more difficult to predict adoption for Black respondents in their sample. The factors explaining adoption seeking for Black respondents included having experienced child death, having been treated for infertility, having attended college, and being older (p.712-713).

Chandra et al. (1999) also examined factors that predict adoption in a sample limited to ever married women between the ages of 18 and 44. The researchers viewed adoption seeking on a continuum from simply considering adoption to actually planning to adopt and taking steps toward adoption. Results showed that over one-quarter of married women in this large, representative sample had considered adoption but only 15.9% of those considering adoption had taken any steps in the adoption process. Slightly over one percent of the women in the sample reported they were currently seeking or planning to adopt. However, only around one-half of these women had actually taken steps toward adoption. Factors explaining considering adoption included age, having no children, having impaired fecundity, having used fertility services, and having higher income. Women having taken steps in the adoption process also tended to be older in age, had no children, had impaired fertility and had used fertility services. Women currently planning to adopt had characteristics similar to the women who had taken steps in the adoption process (Chandra, et al., 1999).

In an analysis of the same data (1995 National Survey of Family Growth) utilized by Chandra et al. (1999), Hollingsworth (2000b) found inter-racial differences in the factors predicting having ever sought to adopt a child. Age, childlessness, and fecundity impairment were associated with adoption seeking among both Black women and White women. However, additional resource-related variables were also significant predictors of adoption seeking for White women, but not for Black women. These included being married, having some college education, considering religion to be very important, having received treatment for infertility, and having received assisted reproductive technology.

In a report of the findings from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, Jones (2008) reports that approximately one-third of women aged 18-44 had ever considered adoption. Of those considering adoption, about one-sixth had taken steps to adopt; of those having taken steps, about one-fourth had adopted. Consequently, although an estimated 18.5 million women had ever considered adoption, only about 0.6 million had actually adopted. Jones (2009) reported that people who had adopted were more likely to be over 30, married, and to have used infertility treatment services than people who had not adopted. In a multivariate analysis using this same survey data, Lamb (2008) examined the factors affecting adoption seeking behavior in a sample of Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women aged 18 to 44. Findings showed that being married, older, and attending religious services were significantly related to having sought adoption for non-Hispanic White women. For Hispanic women, those born in the United States, those who speak English as a primary language, and those with more household economic resources were found to be significantly more likely to have sought to adopt. For both Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women, infertility, infecundity, and use of infertility services were positively and significantly related to having sought to adopt.

Research clearly indicates that individuals and couples who are experiencing problems related to infertility are more likely to consider adoption and to complete the adoption process (Bachrach, et al., 1991; Chandra et al., 1999; Hollingsworth, 2000b; Lamb, 2008, Jones, 2009). According to one report, women who have used infertility treatment services are 10 times more likely to have adopted than women who have never received treatment for infertility (Jones, 2009). Similarly, Hollingsworth (2000b) shows that women who had been treated for infertility were five times more likely to have contacted an adoption agency or attorney than women who had not received treatment for infertility.

Not surprisingly, infertility is the most commonly given reason for deciding to adopt. According to Cudmore (2005), most heterosexual couples who choose adoption do so because of problems related to infertility. In a sample of 2,587 adoptive parents in California, researchers found that 69% of adoptive parents had adopted due to being unable to have a biological child (Berry, Barth, & Needell, 1996). Utilizing a random sample of married individuals as well as a nonrandom sample of public adoption agency applicants from a midwestern city, Bausch (2006) found infertility status to be one of the most consistent covariates of willingness to adopt. However, this study did not measure whether respondents had received treatment services for infertility.

Although the relationship between infertility and adoption is clear in the research, fewer studies have examined the process whereby people dealing with infertility move from attempting to conceive to pursuing adoption. Findings from a study of 39 infertile heterosexual couples who had adopted a child suggest that adoption was seen as a “backup plan” if infertility treatments were not successful (Daniluk & Hurtig-Mitchell, 2003). Results indicate the couples went through years of medical procedures for infertility while believing “they could always adopt” (p. 392). However, only two of the 39 couples admitted actually believing from the start that they would eventually have to face the decision to adopt. Only eight of the couples took steps in the adoption process while still undergoing fertility treatment; all of the others completed medical treatments for infertility before taking any steps toward adoption. The participants expressed a need to grieve the losses associated with not having biological children while at the same time sensing an urgency to proceed with adoption, due to their advancing age. These issues were magnified in relationships where one member of the couple was willing to consider adoption while the other member was unwilling to do so.

Williams (1992) focused on the adoption attitudes and behavior of 16 childless women and 14 of their husbands. These couples were participating in an exploratory study of parenting motivations for couples seeking in vitro fertilization (IVF). Most of the couples interviewed were doing IVF at the same time they were working on adoption plans. Overall, wives had a far more positive attitude toward adoption than did husbands. However, both of the spouses tended to view adoption as a last resort and as something to fall back on should the infertility treatments not result in the birth of a child. More recently, Turner and Nachtigall (2010) found similar results in their study of low-income immigrant Latino couples who were being treated for infertility. Virtually all of the participants expressed their steadfast desire to parent children by “natural” means, but were guardedly willing to consider adoption if faced with eventual childlessness. However, few had initiated any steps toward adoption.

Goldberg, Downing, and Richardson (2009) examined the transition from infertility to adoption in 30 lesbian and 30 heterosexual couples. All of the couples had tried to conceive before pursuing adoption and all were waiting for an adoptive placement. There is some evidence of resource factors affecting the adoption decision in these couples and consistent with previous research. The average age of the women in the study was about 38, the mean duration of relationships was about nine years, mean family income was $124,000, and the vast majority of the adopting parents (76%) had received a bachelor’s degree or above. Similar to the couples in Daniluk and Hurtig-Mitchell’s (2003) study, most had completed extensive infertility treatment procedures before deciding to stop trying to conceive and move toward adoption. Although there were many similarities between lesbian and heterosexual couples in the transition from conception to adoption, lesbian couples often perceived an easier transition, due to less relational conflict and earlier openness to adoption, with a lesser degree of commitment to having a biological child.

In general, research on infertility and adoption provides evidence that adoptive parenting is viewed as a last alternative to having biological children. Over one million Americans seek fertility treatment each year, compared to only about 60,000 who finalize adoptions of unrelated children (Nelkin & Lindee, 1995). Many couples continue with treatment for infertility indefinitely, with low probability of success and considerable expense (Fisher, 2003).

Overall, the research on considering adoption points to a significant portion of the population having considered adoption at some stage in their lives. One of the issues, however, is how considering is defined within the various studies. Much of the previous research has focused on asking respondents whether or not they have considered adoption (e.g. Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002). However, although a large proportion of the population has considered adoption, a small percentage of these individuals actually go on to adopt a child. Consequently, it is important to determine the factors or characteristics that distinguish those who actively pursue adoption from those who merely consider it as a possibility, in order to develop new strategies that encourage the actual adoption of children in need. In the present study, our approach is similar to that used by Chandra et al. (1999). Women who indicated they had considered adoption were asked if they had taken any steps in the adoption process and, if so, what they did; steps ranged from simply reading information about adoption to adopting a child. This categorization of considering adoption allows us to differentiate between women who have merely considered adoption at some point in their lives from those who are more serious about adopting a child.

Hypotheses

We examine a number of independent variables in order to determine the effects upon considering adoption. Although research on whether or not people consider adoption has focused primarily on married respondents (e.g. Bachrach et al., 1991), we compare married respondents with those who were not married at the time of the interview. Although there is some disassociation in today’s society, parenting is still, to some extent, associated with marriage and we expect that married respondents will be more likely than unmarried respondents both to have considered adoption and to have taken steps in the process. Our hypothesis is consistent with Lamb’s (2008) findings, which show that married people are more likely to adopt than their counterparts. We also examine the effects of age on considering adoption. Women who are older have had more time to consider adoption and we expect a positive relationship between age and having considered adoption. Lamb (2008) also found that women who adopt are older than those who have not sought to adopt.

Race has been found to be an important predictor of informal parenting, fostering and adoption. Beeman (2000), Harris and Skyles (2008), and Schwartz (1992) identified race as one of the significant predictors of a child being placed in kinship care with children of color having a greater chance of being placed in kinship care than White children. Research based on data from the National Study of Family Growth (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2005) finds that Whites are more likely to adopt children who are not related to them while Blacks have a greater likelihood of adopting children who are related to them. Also, the National Adoption Attitudes Survey revealed that Hispanics were more likely to consider adoption than were Blacks or Whites (Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002). Therefore, based on previous research, we expect that White respondents will be less likely to consider adoption than respondents of other racial or ethnic groups.

Another background factor we examine is income. A number of researchers (e.g. Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, 2002; Bachrach, et al., 1991) found no differences via income or education on considering adoption. Other studies, however, show that income is positively associated with considering adoption (e.g. Chandra et al., 1999; Lamb, 2008). Adoption can be a costly pursuit and might be prohibitively expensive for people with lower levels of income. Consequently, we expect that individuals with higher family income will be more likely to consider adoption.

We are also interested in investigating the effect of religiosity on considering adoption, especially since previous research has yielded mixed results. Tyebjee (2003) found that religious beliefs were not associated with interest in adoption, and Bachrach et al. (1991) also found no effect of religiosity on considering adoption. In contrast, Lamb’s (2008) findings showed that attending religious services increased the likelihood of having sought adoption for non-Hispanic White women. Similarly, Hollingsworth (2000b) found that considering religion to be very important predicted adoption seeking for White women, but not for Black women. In their study of 2,587 adoptive parents in California, Berry et al. (1996) reported that 27% of respondents gave religious and/or humanitarian motives for adopting, even though they had no fertility problems. In a smaller sample of adoptive families (113 families from Louisiana and Texas), Belanger, Copeland, and Cheung (2008) also found that religious faith was considered by 64% of their sample to be essential to the decision to adopt. Religiosity was also significantly related to both the total number of children adopted and to the total number of children living in the home (foster, adopted, and biological). However, it should be noted that the respondents in this non-random sample were highly religious overall. In light of previous findings, we expect religion to be positively related to considering adoption in our sample of Midwestern women, the majority of whom are White.

As previously discussed, there is a significant amount of research on the effect of infertility upon adoption (e.g. Bachrach, et al., 1991; Chandra et al., 1999; Daniluk & Hurtig-Mitchell, 2003; Hollingsworth, 2000b; Williams, 1992). People experiencing infertility view adoption as one way to form a family. Lamb (2008) and others found that women with infertility problems were significantly more likely to have sought adoption than other women. We expect that women who identify themselves as someone with infertility problems are more likely to indicate they have considered adoption than their counterparts.

Although there has not been a significant amount of research on attitudes regarding the ethics of infertility treatments, we expect that women who have more ethical issues with infertility treatments (specifically assisted reproductive technologies - ART) are more likely to consider adoption than those who have fewer ethical issues with ART. Halman, Abbey and Andrews (1992) found that couples with infertility issues are more in favor of all infertility treatments than are couples without fertility problems. The exception to this was in regard to adoption, where couples experiencing infertility actually ranked adoption as less favorable than couples without infertility issues.

We also examine whether adoptive parenting is viewed as being as satisfying as biological parenting, and whether this affects women’s propensity to consider adoption. We expect that women who agree that parenting adoptive children would be as satisfying as parenting biological children are more likely to consider adoption. A study by Princeton Survey Research Associates (1997) found that 90% of those surveyed had a positive view of adoption, yet one-half of respondents indicated “that adopting is not as good as having one’s own child” (as cited in Tyebjee, 2003, p. 688). In contrast, findings from the National Adoption Attitudes Survey (2002) show that 80% of respondents agreed that “parents get as much or more satisfaction from raising adoptive children as from raising biological children” (p. 6, as cited in Fisher, 2003). Bausch (2006) found the belief that adoptive parenting is inferior to biological parenting to be significantly related to willingness to adopt at the bivariate level, but not at the multivariate level, suggesting that while respondents may view adoptive parenting as inferior, other variables (like infertility) may override those attitudes.

We also include four other variables in the analysis related to parenting: importance of parenting, having given birth to a child, intent to have another baby, and whether the woman has provided foster care or has otherwise informally parented. Women who rate parenting as more important, those who have not born a child, those who plan to add another child to their family, and those who have informally parented the children of others should be more likely to consider adoption and take steps in the process than their counterparts.

Method

Sample

The data for the present study come from telephone interviews with a representative probability sample of 579 Midwestern women ages 25-50. The data were gathered in the spring of 2002 as part of a pilot study for the National Survey of Fertility Barriers. The average length of the interviews was 35 minutes and contained items related to the respondent’s fertility history, medical and other problems with having the number of children they desired. The survey also includes measures of consequences of infertility and changes in life trajectories. Households were identified through a random-digit dialing sample and screened for the presence of a female between the ages of 25 and 50. In order to insure adequate minority representation, census tracts with forty percent or more minority populations were oversampled. The overall response rate for the study was 63%.

Measures

The dependent variable for the current study is whether the respondent ever considered adoption. In contrast to previous research, we categorize considering adoption into three ordinal categories. One category of respondents consists of those women who had never considered adoption (coded as 0). Nearly 60% of the respondents fell into this category (N=346). The second group (coded as 1) includes women who said they had considered adoption at some point but did not take any steps in the process; this group represents 20.4% percent of the respondents (N=118). The third group (coded as 2) consists of those respondents who considered adoption and took steps in the adoption process. These steps include collecting information and reading about adoption, talking to an adoption agency, placing a classified ad in the newspaper soliciting birth mothers, formally applying to an adoption agency, engaging a lawyer to make arrangements for an adoption, waiting for a placement, being in the process of adopting, or parenting an adopted child. Of the respondents, 19.8% (N=115) considered adoption and took steps in the adoption process.

We examine the effects of 12 independent variables on the dependent variable of considering adoption. Respondents’ age on her last birthday ranged from 25 to 50 with a mean of 38.33 years. Marital status was measured in two categories with “0” representing those respondents who were not married at the time of the interview and “1” representing the married respondents. Sixty-seven percent of respondents were married at the time of the interview. Race was measured through the use of three dummy variables. Respondents were categorized as White (0=no; 1=yes), Black (0=no; 1=yes) or “other” (0=no, 1=yes). Seventy-seven percent of the respondents were White, 14% were Black and 9% were “other”. Family income was measured in twelve categories ranging from less than $5,000 a year to $100,000 or more dollars per year. Religiosity is measured as the mean score of three items (How much do religious beliefs influence your daily life? How often do you pray? How close do you feel to God?). The coefficient alpha for the scale is .77 and a higher score indicates higher levels of religiosity.

Regarding infertility, respondents were asked whether or not they saw themselves as someone who has/had a fertility problem (0=no; 1=yes). Eighty-six percent of the respondents self-defined as not having any fertility problems while 14% identified themselves as having a fertility problem. Also included in the analysis is a scale measuring ethical issues with assisted reproductive technology (ART), indicated by the mean score of six items measuring attitudes toward various ART procedures (insemination with husband’s sperm, insemination with donor sperm, in vitro fertilization, donor eggs, surrogate mothering, and gestational carriers). Respondents were asked to indicate if these technologies had no, some, or serious ethical problems. The higher the score, the greater the ethical problems the respondent has with ART; the coefficient alpha for this scale is .89.

Another scale included in the analysis measures the importance placed on parenting. The scale is a mean score of five items (People without children are just as happy as those with children.; I can see a number of advantages to having no children.; Women who don’t want children are unnatural.; I feel I would be incomplete as a woman if I could not have children.; I can visualize a happy life for myself without children.). The items are scored so that a higher score on the scale indicates the respondent believes parenting is more rather than less important. The alpha for the importance of parenting scale is .68. Another measure of importance focuses on parenting adopted versus biological children: I think I would find parenting as satisfying with adopted children as with my own biological children (four ordinal categories ranging from 1= strongly disagree thru 4=strongly agree).

Other variables related to parenting included in the analysis are whether or not the respondent has previously given birth to a child (0=no; 1=yes), and whether or not the respondent intends to have a(nother) baby (0=no; 1=yes). Finally, we look at the effect of formal or informal child care on considering adoption. This variable consists of either having been a formal foster parent (2.2% of respondents) or taking care of another person’s child informally for an extended period of time (17.9% of respondents). A zero means the woman has never been a foster parent or taken care of a child informally (80.9% of respondents) and a “1” means a respondent has done one or both of these activities (19.1% of respondents).

Analysis

Because the dependent variable has three categories and we want to estimate the odds of considering adoption, multinomial regression is used for the analysis. Multinomial logistic regression is designed for use with polytomous outcome variables. This analysis model allows us to make three comparisons. We compare respondents who have considered adoption and taken steps in the process with those respondents not considering adoption, respondents who considered adoption but took no steps in the process with those respondents not considering adoption, and respondents who considered adoption and took steps with those who considered and did not take steps. Thirty-five cases with missing values on any of the variables in the analysis were excluded, reducing the sample size in the multinomial regression to 544. The missing data were not imputed as when the percent missing in the models is small (6% here) casewise deletion is unlikely to yield biased results (Allison, 2002).

Results

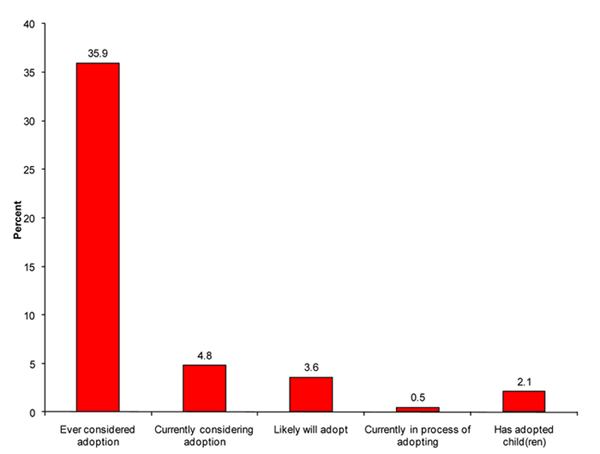

Figure 1 presents the distribution of respondents and their experience with considering adopting. Almost 36% of the respondents indicated that they had considered adopting a child at some point in their lives. About 5% of respondents reported they were currently considering adoption and 3.6% say it is somewhat or very likely they will adopt. One-half of one percent of respondents were in the process of adopting and two percent said they have an adopted child or children.

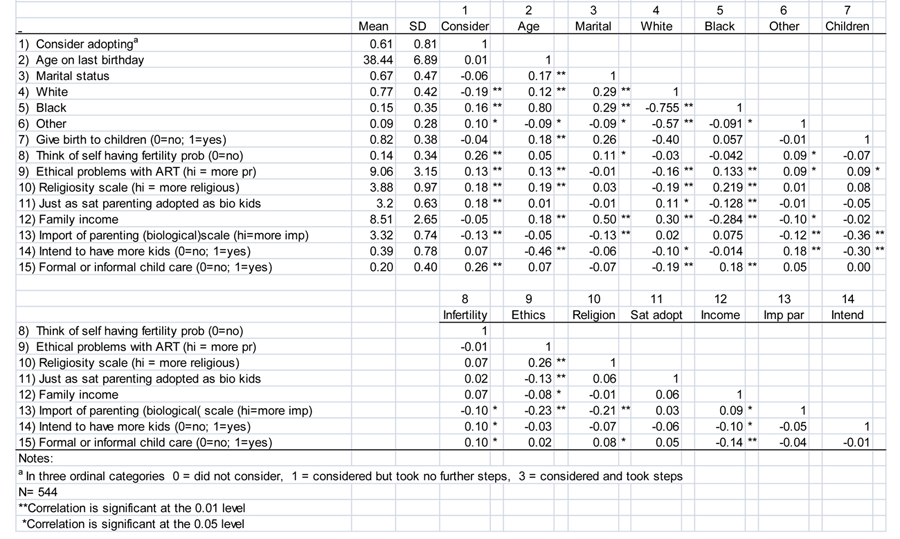

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations for all variables included in the analysis. Considering adoption was significantly correlated with race of the respondent, thinking of oneself as having a fertility problem, having more ethical problems with assisted reproductive technology, having higher levels of religiosity, believing it is just as satisfying to parent adopted children as biological children, thinking of parenting as less rather than more important, and having been a foster parent or taken care of a child for an extended period of time. Interestingly, the only background variable to have a significant correlation with considering adoption is race. Age, marital status, and family income were not significantly correlated with the dependent variable.

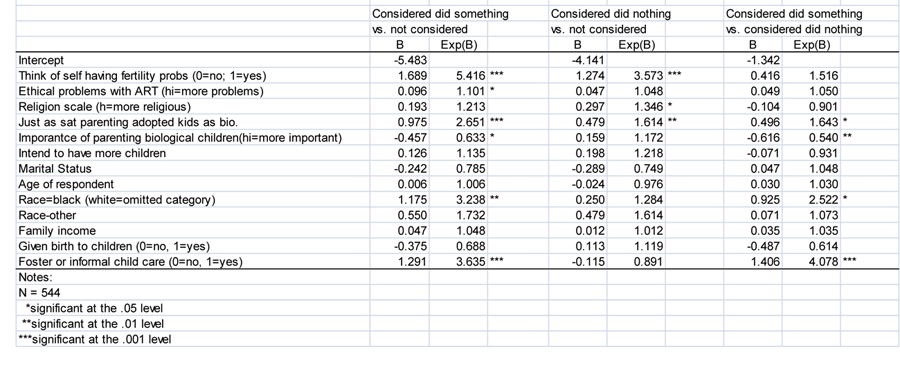

The results of the multinomial regression analysis are presented in Table 2. First, we compared those respondents who considered adoption and took steps in the process with respondents indicating they had never considered adoption. As indicated by the odds ratios, women who think of themselves as having fertility problems were five times more likely to have considered adoption and taken steps in the process as compared to women who did not think about themselves as infertile (p < .001). For each increase in the scale, those women who had ethical problems with assisted reproductive technology were 10% more likely to have considered adoption and taken steps toward adopting (p < .05). Respondents who indicated parenting adopted children is just as satisfying as parenting biological children were three times more likely to consider adoption and take steps toward the adoption process as compared to their counterparts (p < .001). Interestingly, as importance of parenting increased, women were less likely to consider adoption and take steps to adopt (p < .05). Race was a significant predictor of considering adoption and taking steps as compared to not considering adoption at all. Black women were three times more likely to consider adoption and take steps than White women (p < .01). Finally, those women who had fostered informally parented were over 3.5 times more likely to consider adoption and take steps in the process than their counterparts (p < .001).

Table 2 also presents the comparison of women who said they had considered adoption and not taken any steps in the process with those women never considering adoption. Only three of the independent variables were significantly related to considering adoption and not taking steps. Women who thought of themselves as having fertility problems were about three and one-half times more likely to consider adoption and not take any steps in the process (p < .001). Women were also 1.3 times more likely per increase in religiosity to report considering adoption but taking no steps (p < .05). Finally, women who thought parenting adopted children was just as satisfying as parenting biological children were about 1.6 times more likely to consider adoption and not take any steps as compared to those women who believe that parenting adopted children would not be as satisfying. (p < .01).

The final comparison presented in Table 2 contrasts respondents who considered adoption and took steps in the process with those respondents who considered adoption but did not take steps. Respondents indicating it would be just as satisfying to parent adopted children as birth children were 1.6 times more likely to have engaged in steps in the adoption process as compared to considering adoption but having taken no steps to adopt (p < .05). Also, as the score on importance of parenting children increased, respondents were 46 percent less likely to consider adoption and take steps (p < .01). Further, Black women were 2.5 times more likely to consider adoption and take steps in the process than were White women (p < .05). Finally, those respondents who had engaged in foster or informal parenting were four times more likely to consider adoption and take active steps toward adoption than their counterparts (p < .001).

Discussion & Conclusions

In this research, we examined predictors of considering adoption using a three category measurement: have not considered adoption, have considered adoption but taken no steps toward adopting, and have considered adoption and have taken steps in the adoption process. We found that about 36% of the respondents considered adoption, which is consistent with the findings from the Evan B Donaldson Adoption Institute (2002) study.

As expected, those women who considered adoption (but did not take any steps in the process) as compared to women who never considered adoption were more likely to see themselves as someone with infertility problems, have higher levels of religiosity, and were more likely to indicate that parenting adopted children would be just as satisfying as parenting birth children. Infertility and believing parenting adopted children to be just as satisfying as birth children were also predictors of considering adoption and taking steps in the process versus not considering adoption. In addition, those who considered adoption and took steps as compared to those who never considered adoption were more likely to have ethical problems with ART, to score higher on the importance of parenting scale, and to have experience with foster or informal parenting. Black women were significantly more likely than White women to have taken steps toward adoption versus not considering adoption.

Informal parenting experience, race, and agreeing it would be just as satisfying to parent adopted versus biological children were also predictors of actively taking steps in the adoption process as compared to those who considered adoption but did nothing. Interestingly, those women who considered adoption and took steps scored lower on the importance of parenting scale as compared to those who considered and took no steps. The items in the importance of parenting scale focused on parenting birth children. This may account for why those who took steps in the process scored lower on the importance of parenting since their focus is on parenting adopted children and not biological children.

In contrast to previous studies (Chandra et al., 1999; Jones, 2009; Lamb, 2008), resource-related variables such as age, marital status and income were not found to significantly predict consideration of adoption or adoption seeking behaviors. This could be viewed as encouraging in regard to the recruitment of adoptive homes for children. It suggests that non-married women as well as women at all income levels may be equally interested in pursuing adoption. Educating potential adoptive families about the availability of subsidized adoption and no-fee adoptions, especially in regard to the adoption of children currently in foster care, may help to increase the pool of available adoptive families. The finding that women who have provided foster care or other informal child care are significantly more likely to actively pursue adoption is also encouraging. This finding is consistent with Hollingsworth (2000b) who also found foster parenting to be related to adoption seeking for women, especially under certain circumstances such as childlessness and infertility. These results suggest support for foster-adoptive placements when pursuing permanency for children in the foster care system as well as the need for recruitment of potential foster-adoptive families. When reunification with biological parents is not possible, it is often preferable for children to be adopted by parents who are already providing foster care, rather than undergoing another placement and the accompanying experience of separation and loss (Frey, Cushing, Freundlich & Brenner, 2008).

Additionally, the results of our analysis in regard to women’s experiences with infertility provide evidence to support adoption as a viable and desired means of parenting for women with infertility problems, especially for those who may be ethically opposed to assisted reproductive technology.

The results of this study suggest that religiosity affects considering adoption, but not necessarily taking active steps toward adopting. Although the specific religious affiliation of respondents is not included in the present study, religious women in this Midwestern sample are most likely Christian. According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2009), the Midwest most closely resembles the religious composition of the overall U.S. population, which is estimated to be 78.4% Christian. Post (1997) discusses Christian theology in regard to adoption, explaining that Christianity challenges the stigma against adoption that can stem from a dominant cultural emphasis on “blood” kinship, and that Christian ethics suggest that “families can be built as well as they can be begotten” (p.151). This is consistent with our finding that women who considered adoption (but did not take steps) had higher levels of religiosity than those who had never considered adoption. Further research, however, is necessary to more fully understand why religiosity does not influence women to actively take steps toward adoption. An examination of specific religious affiliation and adoptive attitudes and behaviors may give additional insight into this process. Even among a predominantly Christian population, there may be wide variation in attitudes and beliefs concerning, for example, abortion, which might be expected to influence adoption-seeking behavior. Religious groups differ considerably in their official positions on abortion as well as the individual beliefs of their members (Hoffman & Johnson, 2005; Pew Forum, 2009). Future research on this issue may give insight into the process by which pro-adoption, anti-abortion religious values may or may not translate into adoption-seeking behaviors.

In terms of finding adoptive homes for children, our results provide support for involving churches and other religious organizations in the education and recruitment of potential adoptive families, with the goal of encouraging those who may already be considering adoption to move forward in the process. Belanger et al. (2008) conclude that religious faith may be an asset in increasing adoptions as well as in improving adoption outcomes, especially for Black children, who are disproportionately in need of adoptive homes. Further, there is evidence to suggest that when some church members proceed with the adoption of a child, others may well follow. In an example cited by Belanger et al. (2008), one church member felt called to adopt a child in need, prompting other church members to see the need and receive the required training. Consequently, since 1998, members and friends of Bennett Chapel Missionary Baptist Church have adopted 69 Black and one biracial child (Madigan, 2001 as cited in Belanger et al., 2008).

Finally, our findings suggest that the belief that biological and adoptive parenting can be equally satisfying was significantly related to both considering adoption and taking active steps toward adopting a child. These results emphasize the importance of encouraging (through research, education, storytelling, media, and other means) the belief that parenting through adoption can be just as satisfying an experience as parenting through biological means. Fisher’s (2003) review of the literature indicates that adoption might still have a distinct stigma associated with it in the dominant American culture. The stigma associated with adoption and accompanying fears regarding the process may well inhibit Americans from considering adoption and, for those who consider it, from taking steps toward adopting a child.

While this study provides a greater understanding of many of the factors that influence women’s consideration of and pursuit of adoption, additional research on the processes by which individuals and couples actively pursue adoption is needed to address some of the limitations associated with this analysis. Generalization of these findings is limited by the sample’s restriction to women from one region of the United States. Using national level data, exploring the attitudes and behaviors of men, and the inclusion of respondents’ partners, when applicable, would enhance the information presented here. Additionally, more detailed information regarding religious affiliation, beliefs, and values might provide further clarification of the relationship between religiosity and adoption-seeking attitudes and behaviors.

In addition to implications for further research, the results of this study also suggest implications for recruitment of potential adoptive families for children. Our findings suggest that recruitment efforts should encompass a range of potential adoptive parents, including a wide age range, all income levels, and both married and unmarried women. Directions for targeted recruitment efforts are also suggested by the data. The results indicate support for foster-adoptive placements as well as for an emphasis on the recruitment of foster-adoptive families, as women who fostered or otherwise provided long-term care for a child were more likely to actively pursue adoption. Recruitment efforts that increase familiarity with foster care and foster children, and that walk interested individuals through the process, may be effective in expanding the pool of adoptive parents. Further, based on these findings, adoption should also continue to be considered a viable means of parenting for women who experience infertility, especially for those who may view some assisted reproductive technologies as unfavorable. Information about the adoption process and available resources should be readily available to these women. Finally, an expansion of recruitment opportunities through religious organizations may be warranted, with emphasis on converting positive attitudes toward adoption into actual adoptions.

Raising awareness about the need for and benefits of adoption is important, and likely encourages many individuals and couples to consider adoption. However, there is a need for more emphasis on educating potential adoptive parents about the processes, the various ways to go about adopting. Findings from this and other studies can be useful in informing strategies that encourage individuals to move from considering adoption to taking steps that culminate in the actual adoption of children.

References

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage.

Bachrach, C. A.,London K. A., & Maza, P. L. (1991). On the path to adoption: Adoption seeking in the United States, 1988. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53, 705-718.

Bausch, R. S. (2006). Predicting willingness to adopt a child: A consideration of demographic and attitudinal factors. Sociological Perspectives, 49, 47-65.

Beeman, S. K. (2000). Factors affecting placement of children in kinship and nonkinship foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 22, 37-54.

Belanger, K., Copeland, S., & Cheung, M. (2008). The role of faith in adoption: Achieving positive adoption outcomes for African American children. Child Welfare, 87, 99-123.

Berry, M., Barth, R. P., & Needell, B. (1996). Preparation, support, and satisfaction of adoptive families in agency and independent adoptions. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 13, 157-183.

Chandra, A., Abma, J., Maza, P., & Bachrach, C. (1999). Adoption, adoption Seeking, and relinquishment for adoption in the United States. Advance Data, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 306, 1-16.

Creedy, K. B. (2001). Community must unite if perception of adoption is to change. Adoption Quarterly, 4, 95-101.

Cudmore, L. (2005). Becoming parents in the context of loss. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 20, 299-308.

Daly, K. J. (1994). Adolescent perceptions of adoption: Implications for resolving an unplanned pregnancy. Youth and Society, 26, 330-350.

Daniluk, J. & Hurtig-Mitchell, J. (2003). Themes of hope and healing: Infertile couples’ experiences of adoption. Journal of Counseling and Development, 81, 389-401.

Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute (1997) Benchmark Adoption Survey: Report on the Findings. (pp. 1-49), Washington D.C.: Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute.

Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute (2002) National Adoption Attitudes Survey. In E. B. D. A. Institute (Ed.). (pp. 1-48), Dublin Ohio: Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption and The Evan B. Donaldson Institute.

Fisher, A. P. (2003). Still “not quite good as having your own”? Toward a sociology of adoption. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 335-361.

Freundlich, M. (1998). Supply and demand: The forces shaping the future of infant adoption. Adoption Quarterly, 2, 13-46.

Frey, L., Cushing, G., Freundlich, M., & Brenner, E. (2008). Achieving permanency for youth in foster care: Assessing and strengthening emotional security. Child & Family Social Work, 13(2), 218-226. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2007.00539.x

Goldberg, A. E., Downing, J. B., & Richardson, H. B. (2009). The transition from infertility to adoption: Perceptions of lesbian and heterosexual couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 938-963.

Halman, L. J., Abbey, A., & Andrews, F. (1992). Attitudes about infertility interventions among fertile and infertile couples. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 191-194.

Harris, M. S., & Skyles, A. (2008). Kinship care for African American children: Disproportionate and disadvantageous. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 1013-1030.

Hoffmann, J. P., & Johnson, S. (2005). Attitudes toward abortion among religious traditions in the United States: Change or continuity? Sociology Of Religion, 66(2), 161-182.

Hollingsworth, L. D. (2000a). Sociodemographic influences in the prediction of attitudes toward transracial adoption. Families in Society, 81, 92-100.

Hollingsworth, L. D. (2000b). Who seeks to adopt a child? Findings from the National Survey of Family Growth (1995). Adoption Quarterly, 3, 1-23.

Jones, J. (2008). Adoption experiences of women and men and demand for children to adopt by women 18-44 years of age in the United States, 2002. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics, 23(27), 1-37.

Jones, J. (2009). Who adopts? Characteristics of women and men who have adopted children. NCHS Data Brief (No. 12). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Katz, J. (2008). Adoption's number mystery. The Washington Post, p. A17.

Kreider, R. M. (2003). Adopted children and stepchildren: 2000. Census 2000 Special Reports (pp. 1-22), Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce.

Lamb, K. A. (2008). Exploring adoptive motherhood: Adoption-seeking among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women. Adoption Quarterly, 11, 155-175.

Margolis, M., Elkin, M., Nemtsova, A., Polier, A., & Lee, B. J. (2008, February 4). Who will fill the empty cribs? International adoptions are on the decline, despite growing demand and an endless supply of orphans. Newsweek, 151 (5).

Mosher, W. D. & Bachrach, C. A. (1996). Understanding U.S. fertility: Continuity and change in National Survey of Family Growth, 1988-1995. Family Planning Perspectives, 28, 4-12.

Nelkin, D. & Lindee, M. S. (1995). The DNA Mystique: The Gene as a Cultural Icon. New York: Freeman.

Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. (2008) Religious Groups’ Official Positions on Abortion. Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/Abortion/Religious-Groups-Official-Positions-on-Abortion.aspx

Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. (2009) U.S. Religious Landscape Survey. Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/reports

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1-65.

Turner, D. & Nachtigall, R. D. (2010). The experience of infertility by low-income immigrant Latino couples: Attitudes toward adoption. Adoption Quarterly, 13, 18-33.

Tyebjee, Tyzoon. (2003). Attitude, interest, and motivation for adoption and foster care. Child Welfare, 82, 685-706.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2003). Adopted children and stepchildren: 2000. Census 2000 Special Reports. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved July 14, 2004 from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-6.pdf.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. (2011). Preliminary Estimates for FY 2010 as of June 2011 (18). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb.

Whatley, M., Jahangardi, J., Ross, R., & Knox, D. (2003). College student attitudes toward transracial adoption. College Student Journal, 37, 323-326.

Williams, L.S. (1992). Adoption actions and attitudes of couples seeking in vitro fertilization. Journal of Family Issues,13, 99-113.