Gender, Space, and Objects in Divorced Families*

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

*Please address all correspondence to Dr. Michelle Janning, Associate Professor of Sociology and Assistant Dean of the Faculty, 240 Maxey Hall, Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA 99362; Phone:509-527-4952; Fax: (509) 527‐5026; Email:[email protected].

Abstract

Applying symbolic interactionism and a social constructionist perspective on gender roles, and referencing work by Belk (1988) and others on the significance of artifacts and spaces in the creation and revision of social roles during life transitions, we perform an investigation of 22 in-depth interviews with young adults whose parents divorced while they were children or adolescents. We attempt to find out how these young adults experience the presence or absence of traditional gender roles within the post-divorce family as manifest in the use and domestic space and objects. Patterns in the data reveal relatively traditional gender roles as manifest in the use of spaces and objects for mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons. Additionally, efficacy over space and objects is an important part of the post-divorce experience for children.

Key words: divorce, gender, material culture, parent-child relations, space

Scholars have conducted extensive research on the significance of divorce for children, adolescents, and young adults (e.g., Hetherington, 2002; Wallerstein, Lewis, & Blakeslee, 2000), and on how divorce differentially impacts sons and daughters, and mothers and fathers (e.g., Booth & Amato, 1994a; Furstenberg, 1990). We seek to tie this body of work to its manifestations in material culture (physical artifacts that hold social meaning in people’s lives) and home spaces by applying a symbolic interactionist approach to an analysis of in-depth interviews and surveys from 22 young adults in the Pacific Northwest whose parents divorced while they were children or adolescents. Young adulthood (late teens and early twenties) is a particularly useful developmental stage in which to ask about past divorce experiences because it is a time when identity salience and behavior patterns and roles stabilize (Needham & Austin, 2010).

Specifically, we ask the question: How do young adults whose parents divorce experience the presence or absence of traditional gender roles as manifest in the use of domestic space and objects? We presume that the collection, arrangement, and use of artifacts and spaces in adolescents’ homes reflect how families “do gender” (West & Zimmerman, 1987) and reflect perceptions of and relationships with each parent after their parents’ divorce.

Background

Gender and Family Dissolution

Gender roles, or the set of behavioral and attitudinal expectations and patterns of expression that a culture defines as desirable for men and women, and girls and boys (Andersen 20003), are socially constructed in interactions and influenced by institutional norms. Social actors “do gender” (West & Zimmerman, 1987) by enacting and displaying masculine or feminine roles in interactional processes. These roles are affected by patterned collective expectations about what it means to be feminine or masculine (Coltrane, 1998). The family is a gendered institution, such that men’s and women’s roles therein are manifest at the interactional level and are also shaped by structural forces such as labor force participation rates, cultural ideals about gender, and patriarchal relations (Andersen, 2000; Baca Zinn, Eitzen, & Wells, 2011). Therefore, despite gender being socially constructed, and thus susceptible to revision, role expectations for men and women still differ in families (Wharton, 2005).

Since it is in families, as primary socializing agents, where gender roles are first introduced, it is important to investigate how and whether different family structures may produce different types of roles. In fact, there is a large body of research on differential divorce experiences for men and women, often referred to as “his” divorce and “her” divorce. Citing increased freedom and improved standard of living for men, and decreased standard of living and isolation for women, scholars who investigate the gendered divorce experience for men and women focus primarily on economic inequality, with men’s socioeconomic status likely to be higher than women’s (Baca Zinn, Eitzen, & Wells, 2011).

Research on the gendered effects of divorce on parent-child relationship quality provides mixed findings. Some scholars suggest that mothers’ relationships with their children largely are unaffected by divorce (White, Booth, & Edwards, 1986), whereas others (Umberson, 1992) show that the mother’s decline in financial resources following a divorce may add strain to the parent-child relationship. Overall, mothers tend to maintain stronger emotional relationships with their daughters than their sons (Lawton, Silverstein, & Bengtson, 1994b), while fathers experience a general weakening of relationships with their children after divorce (Seltzer, 1994), especially with their daughters (Booth & Amato, 1994a).

The Impact of Divorce on Children’s Gender Roles and Attitudes

Researchers also discuss how and whether divorce affects children’s attitudes about men’s and women’s roles in society (Booth & Amato, 1994b; Kiecolt & Acock, 1988; McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003). Research on both single mothers’ and single fathers’ roles in post-divorce families suggests that children in these families often see models of nontraditional gender roles because both parents usually have greater simultaneous responsibilities of household chores, parenting, and providing financial security to the family than parents who are still married (Glass & Finley, 2002; Hilton, Desrochers, & Devall, 2001; Hilton & Devall, 1998; Leve & Fagot, 1997). However, despite the likelihood of divorced parents to take on nontraditional gender roles following a divorce, some research does not support the notion that children’s gender role attitudes will be directly affected by divorce (Booth & Amato 1991; Kiecolt & Acock, 1988). Other research (e.g., Russell & Ellis, 1991) suggests that children from single parent households tend to hold less traditional attitudes, especially if the single parent households are mother-headed. The effect of coming from a nontraditional family structure, therefore, may have an effect on children’s gender role attitudes, but the effect is likely to be small and dependent on the gender of the custodial parent (Patterson, 2000).

In sum, past research on gender and divorce has focused on inequalities and differences in roles between mothers and fathers, on parent-child dyad relationship quality, and on children’s attitudes about gender role expectations. It is clear from previous investigations that the effect of divorce on children’s gender roles and attitudes is complex, and that other variables may matter in this question. What is less commonly discussed are the effects of divorce on sons’ and daughters’ gender role behaviors and displays, and the inclusion of space and objects as locations for enactment of these gender roles. Because research findings are mixed, and because the inclusion of space and artifacts is missing from past research, we seek to add richness to the body of research on the relationship between divorce and gender by asking young adults about their previous and current experiences with spaces and objects in both parents’ homes.

Symbolic Interactionism: Spaces, Objects, Gender Identities, and Social Roles

Symbolic interactionism suggests social actors relate to their environments via meaning-laden symbols and interpretive interactional processes that help people learn and respond to collectively-accepted norms and ideals (Mead & Morris, 1934; Smith et al., 2009). Internal meanings, or personal interpretations of experiences, are connected to external behavior and display (Longmore, 1998) because social actors take into consideration others’ appraisal of their behaviors when enacting them (Mead & Morris, 1934). Whether and how meaning is attached to symbols depends on how social actors relate to each other and to these symbols.

There are two conceptual areas where assumptions within symbolic interactionism are applied to the divorce experience for the young adults in this project. First, objects and spaces themselves can serve as symbols of socially constructed roles, especially during transitions that occur as a result of family dissolution. Second, the construction, revision, and enactment of roles, as they are manifest in domestic spaces and objects, demonstrate the active interpretation of what is being modeled and learned regarding gender in post-divorce families.

The Significance of Space. Spaces are doubly constructed: first, by their literal physical characteristics and second, by the interpretation, understanding, and narration by their inhabitants (Soja, 1996). Werlen (1993) claims that space is a force that has a detectable and significant impact on social life. The home is a social and cultural unit that reflects and affects shared cultural understanding, family roles, and personal identity (Moore, 2000). People develop bonds with places based on length of time spent in the location, satisfaction with the space, and the amount of personal identity found within the place (Altman & Low, 1992), making home spaces logical locations for the examination of role negotiation in family transitions.

The Significance of Objects. Possessions reflect roles (Belk, 1988). Not only can objects reveal information about their owner to others, they also help the owner develop and present his or her sense of self-identity, and cope with change or transitions by maintaining consistency across time. When physical things are used as representations of roles or as a focus in identity narratives, individuals give them significant meaning (Whitmore, 2001). The accumulation of objects, such as travel mementos, photographs, or childhood belongings, can provide social actors with the ability to acquire a sense of self and therefore receive ontological proof of identity (Noble, 2004). Importantly, material objects can provide social actors with identity continuity and role clarity, particularly during life transitions. Cherished items can assist social actors as they maintain and revise roles (Kroger & Adair, 2008); further, these items can signify to others what parts of their roles are worthy of display (Traver, 2007). Therefore, a bedroom that is occupied by a child for many years may cause him or her to personally identify with the room and the objects found within it. These items contained in a bedroom may then be used by a child to cope with a transition such as divorce, and may serve as cherished (or not-so-cherished) childhood possessions for young adults reflecting back on the divorce experience.

Gender, Space, and Objects in Families. According to Childress (2004), it is important to study the territory of children, teenagers and young adults because little public or private space is deemed theirs in today’s society. Adolescents and young adults in particular construct their bedrooms to highlight spatial arrangements and possessions that reflect their developing self-concept, tastes, opinions, and beliefs. If roles are manifest in objects and physical spaces (Belk, 1988; Bengry-Howell and Griffin, 2007; Jantzen, Ostergaard, and Vieira, 2006; Kroger and Adair, 2008; Noble, 2004;Traver, 2007), there needs to be further analysis of personal space and objects as a method of evaluating this social group’s experiences. The use of objects and spaces may seem like a superficial by-product of the role negotiation involved in divorce experiences, but, in fact, objects and spaces can represent visible role enactment and often can serve as salient locations that hold meaning for people who are reflecting on life transitions, and for people who are in a developmental stage where roles are being more clearly defined.

Gender roles may be symbolized by the management and display of possessions (Pink, 2005), and activities that relate to the accumulation of material artifacts such as travel, school activities, and family rituals (Bengry-Howell & Griffin, 2007; Jantzen, Ostergaard, & Vieira, 2006, for examples). Fathers and mothers tend to differ in how they socialize their children. One result of this is that children are more likely to feel closer to, and talk about a wider range of topics with, mothers as compared with fathers (McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003). Traditionally, women are socialized to provide emotional support and maintain the aesthetic appeal and comfort of home spaces, while men are socialized to provide the economic support for the acquisition of material goods and services that the family can use and display (Madigan & Munro, 1996). Often fathers’ involvement with their children is centered on partaking in leisure time activities, such as playing video games, or on outdoor or mechanical chores (Collins & Russell, 1991; Larson, Gilman, & Richards, 1997), while mothers tend to spend their time on caregiving.

These trends also are observed in divorced families, despite the tendency for nontraditional gender roles to be associated with the creation of separate homes (Jenkins, 2009; Swinton, Freeman, & Zabriskie, 2009). Children of divorced parents frequently refer to their visiting fathers as “weekend daddy,” “McDonald daddy,” and “amusement daddy” because of the types of activities that fathers encourage for their children, and the type of objects that are used in these activities (Haugen, 2005). According to past research, then, the material manifestation of these roles for fathers tends to come in the form of vacation-like locales and objects, and for mothers it often comes in the form of creating comfortable home spaces. These roles are not universal, nor are they representative of increasing numbers of families, but a boundary does still seem to exist between mothers’ and fathers’ role expectations in families as they relate to space and objects, which is reproduced generationally even in divorced families.

Children’s Experiences. As children interact with their environment they develop a sense of value for the tasks they perform (Bussey & Bandura, 1999), such as playing with gendered toys (Pomerleau et al., 1990) or decorating a bedroom with gender-specific artifacts (Collins & Janning, 2010; Sutfin et al., 2008). Pomerleau et al. (1990) and Rheingold and Cook (1975) investigated children’s bedrooms and found that boys’ bedrooms contained more varieties of toys, more sports equipment and machines, and more animal décor items than girls’ bedrooms, while girls’ bedrooms contained more dolls and domestic toys. Additionally, the use of space differs for boys and girls, with boys having larger spaces in which to perform exploratory and physically active play, and girls having smaller spaces in which to perform play associated with the domestic realm (Jenkins, 1998). Boys and girls thus learn gender roles by interacting with gendered objects and by having access to different types and sizes of spaces. If it is the case that gender roles can be represented, and sometimes facilitated, by objects and use of space, it is important to investigate whether the use of these objects and spaces for children of divorce represents non-traditional or traditional gender roles.

The spaces that are allotted to young adults in which they can construct, alter, and present their roles are crucial terrain for sociologists interested in gender roles and familial relationships because they offer a unique window into the lives and meanings of young people. In particular, understanding how material culture functions in more than one home space can shed light on the gendered familial dynamics occurring under each parent’s roof for children of divorce. There is a paucity of research that examines gender roles in divorced families among parents and children through the lens of space and objects. Divorce provides a unique context in which to examine the material culture and spatial representation of post-divorce parent-child experiences, because it is a particularly salient life transition for anyone experiencing it. Further, whether there are differences between mothers’ and fathers’ homes, and between sons’ and daughters’ experiences, can illuminate the gendered patterns associated with divorce. We aim to explore how young adults whose parents have divorced experience the presence or absence of traditional gender roles within the family as manifest in the use of domestic space and objects.

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

The data for this research were collected as part of a larger semi-structured interview study with young adults from divorced families on how the space and objects at each parent’s home impact their identity formation, roles, and relationships. A purposive sample was used in order to interview participants who were old enough to have recollections and opinions of their childhood, and young enough that they remember clearly what it was like dividing their time between two houses as an adolescent. Eligible participants included those whose parents were divorced and who had grown up splitting their time between two parents’ homes for some time.

All participants were members of families with at least some shared custody, and spent either equal time between parents or more time with their mothers. This makes our sample relatively similar to the larger population, at least in terms of custody arrangements. Our participants, as is the case with most divorced families, experienced fluctuations in their visitation schedule as they grew up, and were gradually given more liberty to determine when and where they wanted to spend their time. In fact, each person took the first five to 15 minutes of their interview simply trying to recall and explain the particulars of their complex visitation schedules. In the years following their parents’ divorces, 20 of 22 participants spent roughly 2/3– 3/4 of their time at their mothers’ homes, while only two followed a 50-50 schedule.

All participants noted their primary residences as being located in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, or California. Most participants (19) were White, Non-Hispanic and from self-reported middle to upper classes. Seven of 22 reported religious affiliations. All participants but one had parents who divorced when they were age 11 or younger; 15 had parents who divorced when they were age 7 or younger. Twelve of 22 participants currently have stepmothers and 12 of 22 have stepfathers. All but one participant had one sibling or more, and ten had at least three siblings. All but one of the participants were part of a family with two heterosexual parents pre-divorce. In the case of the individual with two mothers, we discussed the dissolution of his parents’ partnership rather than a legal marriage. Two participants had heterosexual parents who divorced and whose mothers subsequently became involved in same-sex relationships. In these circumstances, we discussed the post-divorce home environments with their fathers at one home and their mothers with their female partners at the other home.

Twenty-two participants (9 male and 13 female; ages 18-22) were recruited from the researchers’ professional and social networks and interviewed by the second author in 2007, primarily in either the participants’ mother’s or father’s homes, or, in some cases, in a neighborhood coffee shop with a visit by the interviewer to one or both homes afterward when permitted by time and geography. Interviews lasted 1-2 hours. In some cases, participants were not comfortable allowing the interview to take place in one parent’s house because of the negative nature of that parent-child relationship. Each participant completed a short demographic survey. Pseudonyms were assigned to all participants.

Topics included in the semi-structured interviews were: living arrangements and visitation schedules over time, young adults’ personal spaces and belongings, the process of switching between homes, parental influence and involvement in participants’ spaces, interactions and relationships with parents, and familial experiences post-divorce. Participants reflected on both past and current living situations. In our findings, we make clear whether participants referred to their current or previous domestic spaces, as our interviews addressed their experiences throughout adolescence and young adulthood.

Data Analytic Technique

We implemented a classificatory filing system (Lofland & Lofland, 1984) to sort index sheets containing primary themes (Berg, 2007) for two rounds of thematic coding of interview transcripts. The first round of coding focused on the significance of space and objects in terms of young adults’ divorce experiences generally and parent-child relationship quality specifically (see Collins & Janning, 2010 and Janning, Laney, & Collins, 2010 for other research based on this and subsequent analyses). The second round of coding focused on themes relating to gender roles and parent-child dyad relationship characteristics. Nvivo (QSR International Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) software for qualitative research was used to organize the data, both in terms of establishing and organizing the aforementioned initial themes found in the data, and in terms of thematic connections. We used components of the constant comparative method (Glaser & Straus, 1967) to compare incidents in our initial thematic categories, seek themes that emerged from the transcripts, relate salient themes together, and check transcripts to include all places in the interview transcripts where these themes were present.

Findings and Discussion

Our participants’ interpretations of their bedroom spaces and objects, and their constructions of relationships with both parents after a divorce, reveal gender differences. Those patterns are complicated by the qualitative characteristics of mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son relations that are structured by post-divorce living situations.

The purpose of the children’s bedrooms when they are not at a parent’s home, and the objects and activities that are used to bond with children within homes, vary between mothers and fathers. More specifically, mothers usually preserve children’s spaces for them to come home to and fathers often use children’s spaces for purposes such as work or exercise. For children, the primary way daughters discuss objects and spaces often relates to comfort and emotional closeness to their mothers’ homes, whereas sons provide primarily utilitarian and hobby-related explanations. Additionally, efficacy over space and objects is an important part of the post-divorce experience for all of our participants, as both sons and daughters appreciate having control over their private spaces in both mother’s and father’s homes, regardless of differences in gender roles. Gender is the primary organizing variable for these findings, with mothers and daughters discussed in sequence, followed by fathers and sons. Detailed descriptions of particular parent-child dyads (e.g., mothers and daughters, fathers and sons) are discussed throughout the findings.

Mothers: Privacy and Preservation

When asked how often their parents entered their bedroom, all participants stated or suggested that their bedroom was a private domain. They frequently emphasized such words as “sacred,” “private,” and a “sanctuary” when discussing what they valued about their bedrooms. The perception about mothers seemed to suggest they are aware of the importance of privacy if that need was established. Matt explained, “My mom never goes in my room anymore...and one, it’s definitely my space, two... there are things in there that I value and that I don’t really want her to look at and she understands that.” By respecting their child’s bedroom as private, mothers demonstrate their belief in the importance of honoring a sacred space. Nearly all male and female participants were likely to say that their mothers, more than their fathers, manifest, in word and deed, an understanding of their children’s need for personal space in their bedrooms. This was true while the participants were growing up, and currently.

Despite the understanding of the need for private spaces for children by mothers, parents were sometimes allowed to enter their room to talk to or spend time with their child. Most commonly, and perhaps in contrast with the aforementioned finding relating to mothers’ respect for children’s privacy, all but a few participants reported that their mothers spent more time in this private realm with them than their fathers did. Mothers were more often than fathers invited into their children’s rooms, and these visits were most common between mothers and daughters who participated in “mother/daughter chats.” Thus, while mothers seem to be aware of respecting privacy, they are also more likely than fathers to ask permission to initiate entry and be invited to cross the boundary into children’s private spaces, especially with daughters. Perhaps one reason for this is because our participants tend to spend more time at their mother’s home and this room is more clearly delineated as solely theirs, whereas children’s rooms at their father’s home more often double as a storage room, office, or guest bedroom. This might make the bedroom seem more “public,” which may lead a father to feel like permission is not needed to enter the space. This also means the child could feel less like they have a “sacred” or “private” space at their father’s home.

Over half of the participants also stressed the importance their mothers place on preserving the child’s personal space over time. This pattern emerged both in families where the children spent more time at their mother’s home, and in families where the children divide their time equally between homes. Elizabeth elaborated, “My space in Seattle [at my mom’s] is a little more sacred, the door stays closed so the cat can’t come in but also so it’s entered a lot less frequently while I am away.” Allie also said, “My mom was really in favor of not changing the space so that we still had our space to go back to.” By preserving children’s bedrooms regardless of whether children are actually present to sleep in them, mothers, more than fathers, place importance on maintaining a personalized, child-centered, and private space for children within the home – spaces that are meant for children “to come home to” after leaving to spend time at their dad’s house, college, or other places. It may also be the case that mothers preserve their children’s spaces to preserve the salience of their own role as mothers, insofar as the preservation of domestic spaces falls under the realm of women’s gender role expectations.

Regardless of custodial arrangements, when children are away from home, mothers are perceived as more likely than fathers to preserve private spaces for children, and respect those spaces as sacred. In addition, mothers are much less inclined to change the function of a child’s room than fathers are after a divorce, regardless of whether children spend equal time with both parents or more time with the mothers. Thus, the post-divorce role that mothers perform, according to their children, is one of nurturing, devotion to children’s privacy, and preservation of children’s spaces as unchanged portions of the home.

Daughters: Relationship Memories and Mother-Connections

All of the daughters in this study chose to articulate that the rooms at their mother’s home tend to contain objects of emotional significance. When asked what items were meaningful to them at their mother’s house, daughters responded with phrases such as “pictures of friends and experiences,” “scrapbooks,” and “memory type things.” Elsa, for example, said that she prefers her mother’s home because, “I have pictures of my friends up and it feels like it’s mine.” Visual representations of relationships are featured prominently in all daughters’ bedrooms at their mothers’ houses. For example, when asked about objects of meaning at her mother’s house, Paige said, “I do like my room here even though it is cluttered, stuff is everywhere...[because] a lot of them are like memory type things.” For Paige, the memory of relationships is important, even above the cleanliness or level of comfort in her room.

Daughters espoused their desire to create a “cozy” space that reflects who they are. They tend to create these spaces more often at their mother’s homes, partially because mothers are more likely to encourage the creation of these kinds of spaces, and possibly because they spend more time at their mothers’ homes in the first place (noting that the causal relationship between custodial arrangement and preferences may be difficult to unpack). Kelsey said, “At my mom’s house I felt more comfortable, like it was totally and completely my bedroom so I could make it the way I wanted.” Similarly, Allie explained the reasons for keeping her space the same throughout college: “I pretty much like it the way that it is. I wouldn’t change anything. It’s very me and it’s something that I feel comfortable in and I’ve worked really hard with the decorations and everything to make it my own.” The daughters stressed the importance of creating a homelike space at their mother’s home, which seems to reflect the traditional notion that girls and women are “naturally” more interested in, and more expected to manage, the domestic sphere. Childhood gender socialization thus seems to instill traditional ideals, even in divorced families.

Photographs of Allie’s room (top) and Paige’s room (bottom) at their mothers’ homes

Photographs of Allie’s room (top) and Paige’s room (bottom) at their mothers’ homesDespite daughters’ inclination to focus on the display of objects in spaces that signify socio-emotional ties, this is not as evident for most of them in their father’s home. Becky explained, “Dad’s house feels a lot more intentional and my room reflects that a lot because it’s a lot more sparse.” In other words, Becky intentionally decided to leave the room sparse because that is the style of the rest of her father’s home, but that also means that it is emotionally sparse, in a way, as a result of the lack of emotion-laden objects. Elsa further echoed these sentiments: “There’s more like a hotel feeling at my dad’s house, with just all the necessary items there but nothing’s there that makes you feel like you actually belong there.” And Molly explained,

My dad’s place doesn’t really feel like home anymore, especially my room because I haven’t spent time there for so many years. My room has the same furniture and things it had when I was in middle school...I just never really took the time to redecorate because I wasn’t spending significant amounts of time there, so I think part of it is that I didn’t make it my own space; it just still looks exactly the same so it feels like it was home then, but it doesn’t...now.

Thus, while participants may treat staying at dad’s as vacation-like or filled with nostalgia for their past (a notion not dissimilar to mothers’ tendency to preserve spaces, but different in that it is not perceived as intentional by these fathers’ children), this experience carries with it a dearth of emotional ties to the objects within the space.

Photographs of Kate’s bedroom at her mother’s home (top) and father’s home (bottom)

Photographs of Kate’s bedroom at her mother’s home (top) and father’s home (bottom)For daughters, domestic spaces that are important to them tend to have objects of emotional meaning and connection to relationships. They are less likely to devote time to creating or maintaining these kinds of spaces, and less likely to think about what meaningful objects should be present in the spaces, in the bedrooms at their father’s house, however, which is unique for children whose parents divorce.

Fathers: Utility and Technology

With the exception of two participants’ fathers, both parents were perceived to respect their children’s bedrooms during times when the child is with the other parent, away at college, or with friends. However, in many of the homes after the divorce, the children’s rooms became a space also used for guests, storage, or exercise. More than half of the participants stated this transformation occurred exclusively at their father’s home. Fathers, who are more likely than mothers to be the non-custodial parent, tend to be more likely than mothers to adapt the rooms to suit more functional purposes, rather than to preserve it as their child’s private space. Becky’s home situation exemplified this finding when talking about her bedroom at her father’s home:

It was an office for...his employee, and when it wasn’t, it was a storage place. But before that it was mostly my room, but at my mom’s it’s been my room since we moved in...I think I just don’t feel like [it’s] home as much [at my dad’s because]...he took that as a sign that he could renovate my room and use it for storage for a couple of years, so that kind of just made it feel less mine, like, I don’t have any attachment to that world at all.

This example suggests that participants perceived their fathers as less likely to preserve spaces as dedicated children’s spaces. It also suggests that less personalized space can make a child feel as if she has less efficacy over her home spaces, and less connection to the “world” of her father. It is possible that some of these fathers’ spaces have been renovated to be multi-purpose because they were not custodial parents, thus rendering the decision more practical than anything else. However, it is difficult to discern whether our participants’ fathers would have been more likely to preserve their children’s bedrooms if they had a greater proportion of custody. Interviews with parents on this topic would therefore be a helpful direction for future research.

In addition to the likelihood of fathers to change the function of their children’s sleeping spaces after a divorce, they are also more likely than mothers to try to connect to their children using entertainment, leisure activities, and technology. Much like the idea of “McDonald daddy” (Haugen, 2005), over half of the fathers in this study provided leisure activities or technological items that the participants had less access to at their mother’s home. When participants were asked to describe their room or the time spent at their father’s house, the most common response included spending a large amount of time watching television. Fourteen of 22 participants stated that they watch more TV, have cable, or have a TV in their bedroom at their father’s home, as opposed to their mother’s home. Many participants recalled this situation in a positive light. Grace explained, “We had cable TV at my dad’s...so it was always a special treat to go.” The concept of “dad’s house as a treat” was further elaborated by Jeff, who said, “I watched more TV. I had my computer games over there and the video games I would play over there. I ate more less-healthy food...there were more...snacks and junk food around...” These quotes signify that time at fathers’ homes is more centered around leisure activities than time at mothers’ homes is, which is consistent with past research on fathering roles in intact families (Collins & Russell, 1991; Larson, Gilman, & Richards, 1997). The difference that divorce can make for fathers’ relationships with their children is that they may feel increased pressure to ensure that children’s visits are fun and memorable. Therefore, they may offer experiences viewed as “special treats” in order to ensure that their children view their time with their father as enjoyable and worthwhile. Often these treats take the form of technology and media.

Several participants recalled excursions and trips as means for fathers to attempt to maintain strong parent-child bonds. Adam reflected positively on his memories of staying in hotels in Seattle with his dad, or going on picnics with his dad and siblings. Similarly, Lucas, the son of two lesbian parents, identified one of his parents as “mom” and the other as “Sam,” who fills the role of a father in the same material ways as the biological fathers in this study. When Lucas was asked to describe his experience at Sam’s home, he said:

We’d go out and do fun things all the time. Like we had a boat which I like, you know, I love going out on the water so we’d go out fishing. I always liked staying over there because...it was almost like a vacation for me...we’re really healthy and stuff [at my mom’s house] and when I go over there she’d have pizza and soda and it was like “jeez!” She kinda really spoiled me.

Lucas used the term “vacation” to refer to time spent at Sam’s house, suggesting that time there is unusual, filled with leisure activities, and a break from everyday life spent at his mom’s house. Being spoiled by their fathers creates positive memories, but these are memories that are more similar to vacations or birthday parties than to everyday living with family members.

While some participants had positive recollections of leisure experiences at their father’s home, others perceived them as more negative, especially when reflecting on overall relationship quality. When John was asked what first came to mind when he imagined his room at his father’s home, he responded that “...my mom never let me have video games but my dad got me a Playstation, so sadly, I would just sit there and play video games.” Similarly, Ashley said, “we watch a lot of TV at my dad’s; he’s not the most social person, so it’s a bonding activity.” Participants, when reflecting on TV use, noted that there is a lack of interaction between the children and their fathers when television was the focus. Kate said, “At my dad’s house I would spend a lot more time in my room because I had a television there, but I didn’t really keep as much stuff there.” For these participants, the relationship with their fathers is manifest primarily in forms that make in-depth conversations or close interpersonal bonding challenging.

Fathers are thus more likely than mothers to spend time with their children via leisure and technology. Participants seemed to have mixed feelings about this, with more people discussing the benefits of such activities and tools than not, but with a few reflecting that these kinds of activities and objects signify a challenge to developing a close interpersonal bond with their fathers. This phenomenon may very well be more a result of these fathers’ tendency to connect with their children via traditional masculinity: providing economic support and engaging in physical or technological play activities. Because mothers traditionally fill an emotionally supportive parenting role, and likely did so before a divorce, nonresidential fathers may struggle when they are required to find ways to enact this role as well, unlike before a divorce. Kate explained, “He had more money so he was always willing, like, when I bought a cello, even just recently I bought a bike, so he [said,] ‘Oh yeah, I can pay for that’ and that’s...his way of being there.” Similarly, Elsa described her father: “[he’s] trying to be a dad on a physical level, like, buy me presents...”

It would be beneficial to ask fathers what their goals are when using leisure activities, technology, and gifts as tools for parent-child relationship building, especially in cases where they have limited visitation with their children, but the participants’ reactions tell us that the outcome is both positive and negative. Fathers are less likely than mothers to have been socialized to express care and concern for children in emotionally nurturing ways (McHale, Crouter, & Whiteman, 2003; Wharton, 2005). However, in these participants’ experiences, the notion that fathers’ roles are relatively traditional diverges from past research on divorced fathers’ likelihood to take on both traditionally masculine and feminine roles in their homes more than married fathers (Glass & Finley, 2002; Hilton, Desrochers, & Devall, 2001; Hilton & Devall, 1998). Thus, when compared with fathers in intact households, divorced fathers may perform more expressive roles; but when compared with mothers (as in this study), they do so less often in the form of objects and spaces. This makes these participants’ experiences similar to children in intact families.

Sons: Autonomy and Utility

Similar to daughters, the items in sons’ rooms reflect their interests and hobbies. John recollected, “When I was into rollerblading my walls were completely covered up with pictures [of rollerblading].” Sons did not differentiate the quality of experiences between their mother’s and father’s homes as much as daughters did, but they did call attention to their ability to control their bedroom spaces as an important component of the parent-child relationship. There was not as much difference in this kind of efficacy for sons between mother’s and father’s houses as there was for daughters, however. Some sons felt more of a connection to their room, and simultaneously with the parent in whose house the room was situated, if they were: 1) currently living there, 2) “designed it” themselves, or 3) if they had constructed specific objects for the room. This was the case regardless of whether it was at mom’s or dad’s. Jeff explained, “We designed [the room] together because [my dad is] a contractor and so we built it and we came up with these shelves for my books and my TV and my stereo... so that space has more of a personal flavor of me.” In this case, Jeff defined his attachment to a space by articulating that he had control over the building of that space, and that the building project involved a collaborative process between him and his father. Importantly, daughters also expressed the importance of having control of their spaces, but most often this was in terms of the decorations contained therein, rather than the construction of objects or spaces, as discussed above.

Sons seem to have a variety of experiences with their bedroom décor in their father’s home. Some reported having objects of meaning, such as pictures, while many others again described technology as the important objects. However, like many daughters, Adam reflected on the lack of notable memories at his father’s house when he said, “all the stuff [is] from my mom’s house, I don’t really have personal stuff at my dad’s.”

The majority of sons have fewer objects of emotional meaning located in their parents’ homes than daughters do, with the most notable discussion of these objects in reference to their mother’s home. Of the nine male participants, two mentioned the importance of pictures, yet they were not referred to with the reverence or level of detail that females used in their responses. Jeff placed an emphasis on the importance of objects of utility, saying, “Here I have some pictures, those have their emotional value, but not any tangible items that I can use regularly or anything like that.” In contrast to the daughters, sons appeared to refer to technology as more important than decorations with emotional meaning in their bedrooms.

Photographs of Michael’s room (top) and Toby’s room (bottom) at fathers’ homes

Photographs of Michael’s room (top) and Toby’s room (bottom) at fathers’ homesAnother participant, Ben, chose to decorate his walls only with the paraphernalia of the sports and activities in which he participated. He limited his wall decoration to objects that he described as concrete symbols of his roles, perhaps indicating an athletic, adventuresome, no-nonsense person. When asked to describe this room, he explained:

I like the word utilitarian... Because...there’s nothing around that I don’t use... everything has...a purpose, like, there’s nothing on the walls that are...hanging around for me to stare at...I have...a scuba spear, and...my lacrosse sticks are all...hanging on the walls. I have...stuff that I use you know, and my stereo’s on my dresser, and it’s not like it’s bare...there’s stuff in there...The walls aren’t that decorated. But...I don’t like having junk around, so generally, I don’t...have a lot of things on my walls.

The “junk” on “walls” he refers to are the same things on which many daughters placed weighty emphasis – photographs, maps, picture frames, drawings, paintings, etc. Alternatively, when asked about objects of importance in his room, Lucas referred to technology: “it’s got my sound system in there, my X Box... so I can watch TV, play games...” Sons’ focus on technology in their mother’s home suggests that their home spaces have a more utilitarian focus than the spaces that daughters occupy, hence representing more traditional masculinity.

Through these descriptions, it is evident that sons and daughters tend to exhibit traditional gender roles in their spaces at their mother’s home. Additionally, it is clear that daughters feel especially distanced from their father’s home, whereas sons feel satisfied with their spaces at their father’s home if they feel that they have control over the space to use it as they see fit.

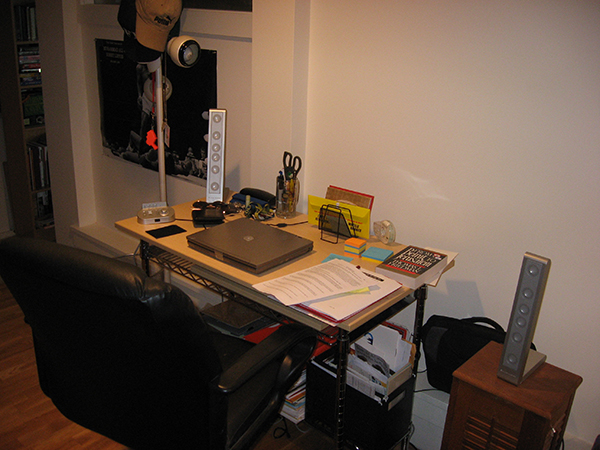

Photographs of Kate’s desk (top) and Jeff’s desk (bottom)

Photographs of Kate’s desk (top) and Jeff’s desk (bottom)Limitations

An important limitation in this study is the retrospective nature of the data. It is quite possible that the relationship quality of a particular parent-child dyad affected participants’ feelings about their spaces, and, considering the time lag between the time of divorce and the time of the interviews, this limitation could be substantial. Also, it is not possible to discern whether space and objects truly capture the relationship dynamics and roles in these families as they undergo a major life transition. While it is not possible to discern clearly whether these patterns would have been present if the families had not experienced divorce, it is possible that an adherence to relatively traditional gender roles in these young adults’ lives could signify a pattern of adherence to stable roles during a time of significant transition. Additionally, because this analysis represents an interpretation of experiences of a unique group of participants, it is important to establish trust between researchers and participants, and to ensure credibility during data collection and analysis. Because the interviewer and the primary transcript coder were of similar ages to the participants and had both gone through many of the same kinds of experiences, the trust of participants and credibility of the interpretation is present. A final limitation to this research is that there were no cases where fathers had more custody, or spent more time with their children, than mothers. Based on these same data, we found in a previous paper (Janning et al., 2010) that parent-child relationship quality and the degree of perceived parental authority are significantly associated with the amount of time a child spends with his/her parent, and also with the amount and type of personalized space they have at parents’ homes post-divorce. Thus, it appears as if custodial arrangements and relationship quality are interrelated. Future research could tease out these distinctions as they relate to gender, which we do not include here. Nonetheless, our current study’s findings reveal that regardless of differences in the quantity of time spent at either location, important themes emerge that suggest that qualitative characteristics of spaces and objects indicate important gendered patterns, and that some of these patterns seem to be specific to the divorce experience itself, rather than just to societal expectations about gender roles.

Emerging Themes

These findings reveal that, in these divorced families, young adults describe traditional gender roles in their families, among both the parents and the children, and in reflections about the divorce transition and time afterward. Although this study does not contain a comparison with young adults in intact families, the findings add complexity to past research investigating the relationship between divorce and gender attitudes. Our findings differ from research (Glass & Finley, 2002; Hilton, Desrochers, & Devall, 2001; Hilton & Devall, 1998) that suggests that parents take on increasingly non-traditional roles in creating two households after a divorce, but align with research that suggests that divorce does not necessarily cause children to hold less traditional views. Future research with a more economically diverse sample could uncover more details surrounding this pattern, as could research on the influence of stepparents on post-divorce domestic transformation. In this analysis, despite the fact that just over half of the respondents have stepparents, there was not a clear relationship between the role of stepparents and their influence on the gender roles of the respondents or their parents. However, we do suspect that the relatively high number of stepparents in this study may have fostered traditional gender roles in the blended families. Since there was another adult in the household of the opposite gender, the divorced parent was not forced to enact the traditional roles of a mother and father. Consequently, traditional gender roles continued to be modeled for their children.

After a divorce, parents’ roles are consistent with larger traditional structural gender patterns. Mothers most often preserve children’s spaces for them to come home to; fathers tend to use children’s spaces for other purposes, often for work or exercise. It is not a coincidence that the preservation of emotion-laden space is tied to women’s increased tendency to create scrapbooks and preserve photos as part of the kinship-keeping process (Chambers, 2003; Grey, 1991). The use of domestic spaces as home offices or gyms by fathers is not inconsistent with previous scholars’ findings of fatherhood ideals being wrapped up in economic provision, leisure activities, and physical strength (Kimmel, 2011). So, when parents divorce, they follow scripts about gender, which in turn affects how their children feel about the spaces they create in separate homes. Adherence to aesthetic transformation in the domestic sphere is part of women’s roles in these young adults’ stories. Most of the participants spent a majority of their time at their mother’s home, which could suggest that time spent in a location can yield closer attachment to the spaces therein. In this case, the custodial arrangements after a divorce may have heightened the level of adherence to traditional gender roles, since many participants spent more time with their mothers.

Children have been socialized in these families to exhibit relatively traditional gender roles in their bedrooms and belongings. The tendency of daughters more than sons to discuss decoration and how photographs and objects signify important personal relationships parallels research findings about girls who choose play tasks and toys that stress nurturing and human connection over toys that stress mechanical or aggressive tasks (e.g., Pomerleau et al., 1990). Complementarily, the inclination of boys interviewed in this study to focus their narrative about relationships with parents on construction, technology, utility, and autonomy, is consistent with masculine ideals for boyhood (Kimmel, 2011). These findings suggest that gender matters in these participants’ experiences regardless of the structure of the family, but also that the particular sentiments they attach to the objects and spaces (and the construction or decoration thereof) may reveal differential parent-child relationship quality that stems from the existence of two separate homes. Thus, we find that a discussion of the relationship with either parent needs to include material culture and spatial arrangements as part of the relationship experience.

Gender differences were not as important as gender commonalities in some ways. It is clear that both sons and daughters appreciate having control over their private spaces in both mothers’ and fathers’ homes. Other research from these data reveal that the size of the spaces matters less than a child’s feeling that he/she has the ability to personalize it (Janning et al., 2010). Thus, efficacy over space and objects is clearly part of the post-divorce experience for children, regardless of gender.

In these central themes, the utility of applying symbolic interactionism becomes apparent, because objects and spaces are discussed by participants as markers of role formation and parent-child relations, and the active interpretation of objects and spaces by our participants demonstrates what is being modeled, learned, and enacted regarding gender in post-divorce families. Adolescents’ use and display of spaces and objects have a significant impact on the daily practices, habits, and visitations involved with growing up in divorced families. The objects in their rooms are symbolic of how they view themselves and also their relationship with each parent. Possessions and spaces can serve as tools for transitions in families dealing with divorce, either as elements of stability and continuity in a time of change, or as elements that symbolize how an individual social actor’s role may be changing or solidifying as a result of the family dissolution process.

There is a clear gendered interplay between material and spatial representations of children’s desires and parents’ offerings after a divorce, and many of these dynamics emerged more clearly because of a divorce. From the stories of these young adults whose parents divorced, we learn that, while it is the case that mothers tend to put effort into making home spaces comfortable and fathers tend to put effort into making home spaces fun and utilitarian, a more complex picture emerges once we add the children’s reflections on their relationships with both parents, and the gender patterns of the children, into the story. The spaces that family members occupy, as well as the objects contained therein, can tell social researchers plenty about these social actors’ experiences during family transitions such as divorce. We attempt here to uncover how domestic spaces and objects and their use are relevant for families post-divorce, and how the bedrooms and belongings of young adults whose parents have divorced are an important part of the parent-child relationship and role definition, especially in terms of gender.

References

Altman, I.,& Low, S. M. (1992). Place attachment. In I. Altman & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment: Human Behavior and Environment (pp. 1-13). New York: Plenum Press.

Andersen, M. L. (2000). Thinking about women: Sociological perspectives on sex and gender. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Baca Zinn, M. D., Eitzen, S., & Wells, B. (2011). Diversity in families, 9th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139-168.

Bengry-Howell, A., & Griffin, C. (2007). Self-made motormen: The material construction of working-class masculine identities through car modification. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(4), 439-458.

Berg, B.L. (2007). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences, 6th edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1991). The consequences of divorce for attitudes toward divorce and gender roles. Journal of Family Issues, 12(3), 306-322.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1994a). Parental marriage quality, parental divorce, and relations with parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 21-34.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1994b). Parental gender role nontraditionalism and offspring outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 865-877.

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106, 676-713.

Chambers, D. (2003). Family as Place: Family Photograph Albums and the Domestication of Public and Private Space. In J. M. Schwartz & J. R. Ryan (Eds.), Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (pp. 96-114). London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

Childress, H. (2004). Teenagers, territory, and the appropriation of space. Childhood, 11(2), 195-205.

Collins, C. & Janning, M. (2010). The stuff at Mom’s house and the stuff at Dad’s house: The material consumption of divorce for adolescents. In D. Buckingham & V. Tingstad (Eds), Childhood and Consumer Culture (pp. 163-177). Palgrave Publishers.

Collins, W. A., & Russell, G. (1991). Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review 11, 99-136.

Coltrane, S. (1998). Gender and families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1990). Divorce and the American family. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 379-403.

Glaser, B., & Straus, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Glass, J., & Finley, A. (2002). Coverage and effectiveness of family workplace response policies. Human Resource Management Review, 12(3), 313-337.

Grey, C. (1991). Theories of relativity. In J. Spence & P. Holland (Eds.), Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography (pp. 106-116). London: Virago Press.

Haugen, G. M. D. (2005). Relations between money and love in post divorce families. Childhood, 12, 507-526.

Hetherington, E. M. (2002). Marriage and divorce American style. American Prospect (April 8), 62-63.

Hilton, J. M., Desrochers, S., Devall, E. L. (2001). Comparison of role demands, relationships, and child functioning in single-mother, single-father, and intact families. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 35, 29-56.

Hilton, J. M., & Devall, E. L. (1998). Comparison of parenting and children’s behavior in single-mother, single-father, and intact families. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage 29, 23-54.

Janning, M., Laney, J., & Collins, C. (2010). Spatial and temporal arrangements, parental authority, and young adults’ post-divorce experiences. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage 51, 413-427.

Jantzen, C., Ostergaard, P., & Sucena Vieira, C. M. (2006). Becoming a “woman to the backbone”: Lingerie consumption and the experience of feminine identity. Journal of Consumer Culture 6(2), 177-202.

Jenkins, H. (1998). ["Complete freedom of movement"]: Video games as gendered play spaces. In H. Jenkins & J. Cassell (Eds.), From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games (pp. 262-297). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jenkins, J. (2009). With one eye on the clock: Non-resident dads’ time use, work and leisure with their children. In T. Kay (Ed.), Fathering through sport and leisure (pp. 88-105). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kiecolt, K. J., & Acock, A. C. (1988). The long-term effects of family structure on gender role attitudes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 709-717.

Kimmel, M. (2011). The gendered society, 4th ed. New York and Oxford: Oxford UP.

Kroger, J., & Adair, V. (2008). Symbolic meanings of valued personal objects in identity transitions. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 8(1), 5-24.

Larson, R., Gillman, S., & Richards, M. H. (1997). Divergent experiences of family leisure: Fathers, mothers, and young adolescents. Journal of Leisure Research 29(1), 78-97.

Lawton, L., Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (1994b). Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family 56, 57-68.

Leve, L., & Fagot, B. I. (1997). Gender-role socialization and discipline processes in one and two-parent families. Sex Roles 36, 1-21.

Lofland, J.A., & Lofland, L.H. (1984). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Longmore, M. A. (1998). Symbolic interactionism and the study of sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 35, 44–57.

Madigan, R., & Munro, M. (1996). House beautiful: Style and consumption in the home. Sociology 30(1), 41-57.

McHale, S., Crouter, A. C., & Whiteman, S. D. (2003). The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Development 12, 124-148.

Mead, G. H., & Morris, C. W. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moore, J. (2000). Placing home in context. Journal of Environmental Psychology 20, 207-217.

Needham, B. L., & Austin, E. L. (2010). Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39, 1189-1198.

Noble, G. (2004). Accumulating being. International Journal of Cultural Studies 7(2), 233-256.

Patterson, C. J. (2000). Family relationships of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1052-1069.

Pink, S. (2004). Home truths: Gender, domestic objects, and everyday life. New York: Berg.

Pomerleau, A., Bolduc, D., Malcuit, G., & Cossette, L. (1990). Pink or blue: Environmental gender stereotypes in the first two years of life. Sex Roles 22, 359-367.

Rheingold, H. L., & Cook, K. V. (1975). The contents of boys’ and girls’ rooms as an index of parents’ behavior. Child Development 46, 459-463.

Russell, C. N. & Ellis, J. B. (1991). Sex-role development in single parent households. Social Behavior and Personality, 19, 5-9.

Seltzer, J. A. (1994). Consequences of marital dissolution for children. Annual Review of Sociology 20, 235-66.

Smith, S. R., Hamon, R. R., Ingoldsby, B. B.,& Miller, J. E. (2009). Exploring family theories, 2nd ed. New York and Oxford: Oxford UP.

Soja, E. W. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Sutfin, E., Fulcher, M., Bowles, R. P., & Patterson, C. J. (2008). How lesbian and heterosexual parents convey attitudes about gender to their children: The role of gendered environments. Sex Roles 58, 501-513.

Swinton, A. T., Freeman, P. A., & Zabriskie, R. B. (2009). Divorce and recreation: Non-resident fathers’ leisure during parenting time with their children. In T. Kay (Ed.), Fathering through sport and leisure (pp. 145-163). New York, NY: Routledge.

Traver, A. E. (2007). Home(land) décor: China adoptive parents’ consumption of Chinese cultural objects for display in their homes. Qualitative Sociology 30(3), 201-220.

Umberson, D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family 51, 845-872.

Wallerstein, J. S., Lewis, J. M., & Blakeslee, S. (2000). The unexpected legacy of divorce: A 25 year landmark study. New York: Hyperion.

Werlen, B. (1993). Society action and space: An alternative human geography. London, England: Routledge.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society 1(2), 125-151.

Wharton, A. (2005). The Sociology of gender: An introduction to theory and research. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

White, L. K., Booth, A.,& Edwards, J. N. (1986). Children and marital happiness. Journal of Family Issues 7, 131-147.

Whitmore, H. (2001). Value that marketing cannot manufacture: Cherished possessions as links to identity and wisdom. Generations 25(3), 57-64.