Thematic Analysis of the Experiences of Wives Who Stay with Husbands who Transition Male-to-Female*

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

*Please address all correspondence to Dr. Gary H. Bischof, Department of Counselor Education and Counseling Psychology, Western Michigan University, WMU-CECP Dept., Mail Stop 5226, 1903 West Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5226;Phone:269-387-5108;Fax:269-387-5090;Email: [email protected].

Abstract

The transgender literature dealing with couple and family dynamics is limited. Married couples with a transgender partner who wish to remain together have minimal information available and few models about how this type of transition might be negotiated. This qualitative study analyzed fourteen cases of the wives of male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals from Virginia Erhardt’s 2007 book, Head over Heels: Wives Who Stay with Cross-Dressers and Transsexuals. The authors used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to identify and organize key themes in the experiences of wives who stayed with MTF transsexual partners. Themes clustered in three main areas: 1) Intrapersonal, 2) Couple Relationship, and 3) Family and Social Relationships. Conclusions from this study and implications for human service professionals are offered.

Key words: couple, couple therapy, male-to-female, transgender, transsexual

Gender Identity Disorder (GID), the clinical condition characterized by a pervasive feeling that one was born the wrong sex and the desire to live as other than the gender that was biologically assigned, affects about 1 in 12,000 to 45,000 natal males and 1 in 30,000 to 100,000 natal females (White & Ettner, 2004). Recently, as a new version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V; the official compilation of mental health diagnoses) was being drafted, many called for this diagnosis to be removed as a mental health disorder, thereby depathologizing what many advocates consider to be a variation of gender identity. Of the genetic males who enter treatment, approximately 50% are either married or have been married, and about 70% have children (White & Ettner, 2004). Genetic females with GID are typically less likely to enter marriages with males, and are also less likely to have children (White & Ettner, 2004). Overall, awareness of transsexuals has increased in society and transgender persons have taken a more prominent place in the LGBT community, though they are still among some of the most marginalized in American society (Lev, 2004).

Transgender literature dealing with couple and family dynamics is limited. In fact, in 2004 Arlene Lev noted a scarcity of professional information on the treatment and support of the families of transgender individuals, and the marriage and family literature is essentially silent on this issue. She further reports that little discussion exists on the needs of committed partners, and the possibility of transitioning within supportive families is rarely suggested. Clinicians who work with transgender individuals often receive calls for support from partners and family members. Lev also noted a subtle homophobia that underlies an assumption that families or marriages cannot survive gender transition and that early guidelines for married transsexuals called for them to divorce before gender reassignment treatment or surgeries were possible. Much of the literature emphasizes the negative aspects (e.g., depression, family issues, job/career challenges) of transitioning on couples and families; yet, there are potential positive aspects and strengths (e.g., being more true to self, resiliency, positive personality changes) of these couples that should be highlighted (Israel, 2004). Unfortunately, couples who wish to remain together have little information available and few models as to how this type of transition might be negotiated (Cohen, Padilla, & Aravena, 2006). This current study aims to address this gap in the literature by examining the dynamics of couples who have stayed together.

Although limited, there is a growing literature specifically focused on couple relationships related to transgenderism. For example, Samons (2009) identified factors (e.g., thorough assessment of the individuals and the relationship, information about wives’ common fears, strategies for coming out, and the broad range of normal sexual behavior) that should be taken into account by a therapist when approaching this work, and stressed the importance of involving the partner of the transgender person early in the process of therapy. Another article focused on the disclosure event within the lifespan, considering the disclosure experience in the context of sexual orientation, ethnicity and cultural/lifestyle factors (Nuttbrock et al., 2009). In terms of the couple relationship, Nuttbrock and associates (2009) emphasize the importance of the timing of the disclosure of one’s transgender identity to one’s partner and the implication of this on the long-term prognosis for the relationship, with better outcomes when one’s gender identity is revealed in the early stages of a relationship. Coolhart (2007) provides an overview of transgender couple and family issues for marriage and family therapists, and notes the importance of assessing couple and family dynamics and actively including partners and family members in the therapeutic process.

Others also have described the lack of attention in the literature and clinical practice to the loved ones of transgender individuals and offer strategies for sensitively and effectively including partners or family members in the counseling process. Bockting, Knudson, and Goldberg (2007) note the increased presentation in community settings of transgender individuals and their loved ones. These authors provide a protocol for community treatment that is guided by three principles: a transgender-affirmative approach, client-centered care, and a commitment to harm reduction. Israel (2005) describes how the lack of family support negatively affects outcomes and that having one supportive family member can garner a successful transition. Malpas (2006) discusses the shift from a sense of “otherness” between partners to creating a supportive alliance over time. Raj (2008) offers a Trans-formative Therapeutic Model that supports the partner in conjunction with the transgender loved one as a cohesive and dynamic systemic unit. The importance of validating emotions, increasing social support, and providing accurate information also is emphasized by Zamboni (2006).

Finally, the Association for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Issues in Counseling (ALGBTIC, 2009), a division of the American Counseling Association, has produced competency guidelines for clinical work with transgender clients that include some attention to couple issues. These guidelines include: creating a welcoming and affirming environment for transgender individuals and their loved ones, assessing and appropriately intervening in family/partner relationships, and being aware of gaps in the literature and research regarding understanding the experiences of and assisting transgender individuals and family members.

Deciding upon the proper language and pronouns to use when discussing gender variance can be complicated. Several authors have written about different ways to describe individuals who do not fit into the traditional Western binary gender model. Girshick (2008) discussed the social construction of gender by exploring the Native American term two-spirit. Two-spirit people are accepted as “individuals whose gender presentation and gender roles do not match their physical body” (Girshick, 2008, p. 22). She contrasts the acceptance of two-spirit people in Native American culture to European persecution of such individuals and forcing two-spirit people to present as their biological sex. Lev (2004) and Coolhart, Provancher, Hager, and Wang (2008) provide specific recommendations for inclusive language when discussing gender variance. Lev (2004) describes transsexuals as individuals whose “issues are decidedly different from other gender-variant people because of their expressed need to physically alter their bodies surgically...” (p. 6). Following her and others’ recommendations, the MTF transsexuals are referred to as “MTF partners,” “transwomen,” or transsexual partner in this paper. Coolhart and associates (2008) advocate for using pronouns which reflect the client’s preferred gender while recognizing the fluid nature of gender expression and focus on understanding “how the client is currently expressing and making sense of gender” (p. 309). In the discussion of themes and patterns found in Erhardt’s narratives we have used the name and gender pronouns preferred by the MTF partner. Male pronouns have been retained in quoted material from Erhardt’s book and other sources.

Research Question

The primary research question guiding this exploration involved identifying key elements of the experiences of wives who stay with their MTF transsexual partners, with particular attention to the psychological and relational aspects of these wives’ experiences.

Methods

Background of Cases

Virginia Erhardt, a clinical psychologist and gender specialist, provides an important view into the experiences of wives coping with their MTF partners’ gender variance in her 2007 book, Head over Heels: Wives Who Stay with Cross-Dressers and Transsexuals. Her book is a collection of narratives written in collaboration with thirty women whose partners identify as cross-dressers, transgenderists, and male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals. The first-person narratives range in length from two to 10 pages, and describe the individual journey of the natal female partner, as well as the simultaneous journey of the couple. One unique element of Head Over Heels is the way in which the manuscript is presented. Each woman shares, in her own style, the details of her unique experiences in the process of coming to terms with her husband’s transgender identity and what that means for the couple. Erhardt provides introductory chapters defining the concepts involved and offers commentary on each case. Erhardt’s contributions might be helpful to both the clinician and the couple as she provides validation and acknowledgement of the challenges experienced, while employing her clinical experience to identify where and how counseling might have been useful. Head over Heels offers a frank look at the reality of couples dealing with this major transition.

This current study included fourteen of Erhardt’s cases, those that identified more clearly as MTF transsexuals, as opposed to cross dressers. It should be acknowledged that not all of these cases are clearly identified, as many men gradually transition and may spend a period of time cross-dressing prior to identifying as a MTF transsexual. Others may desire a gender transition, but have not taken any steps to do so. The 14 MTF transsexuals were living at least in some contexts as a female and had begun some form of gender transitioning.

The 14 couples were married at the time the narratives were written. Seven couples had been married for 20 years or more, and of these couples five were married over 30 years. Three couples were married for 10-20 years, and four were married for less than 10 years. For one couple, both partners had been in a prior heterosexual marriage. One woman reported she planned to divorce when Erhardt conducted a follow-up, but the case was included in the book and in the analyses here. Unfortunately, Erhardt does not report the race or ethnicity of these cases.

Eight couples reported being in stable marriages and being happy or very happy, and described themselves as being best friends or soul mates. Five couples were less certain about the future of their marriage, though all wanted to remain together, and they worried about how the relationship might change as the transition continues. Some wives reported worrying about their MTF partners becoming attracted to men. A final couple remained together, but functioned more separately, living separate lives, with separate bedrooms and bathrooms, and related to each other as good friends.

Data Analysis

Four researchers were involved in this project: one university professor in a graduate counseling and counseling psychology department, one counseling psychology doctoral student, and two couple and family counseling master’s students. Research involved analyzing fourteen cases of wives who stayed with transsexual partners published in Erhardt’s 2007 book Head over Heels. Researchers read the MTF cases and identified preliminary issues. A within-case analysis (Creswell, 1998) was conducted on each case and a preliminary chart was developed to record commonly occurring themes in the experiences of the wives of MTF transsexuals. The organizing chart was modified until all key themes were included and a saturation point was reached (Creswell, 1998).

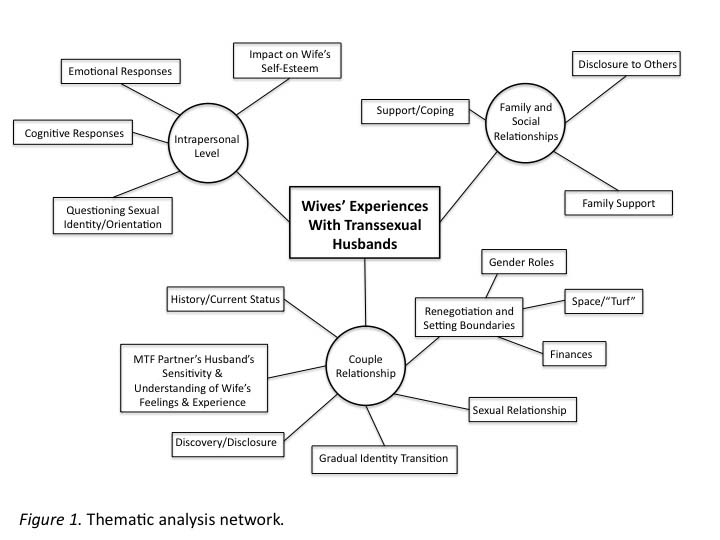

The next step of data analysis involved cross-case analyses of issues identified from the within case analyses and identification of themes, using thematic analysis as the primary qualitative research method (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis provides a flexible and useful tool to identify and organize key themes from qualitative data. The team of researchers analyzed the main issues across cases, and using consensual decision making, came up with key themes in the experiences of wives who stay with MTF transsexual partners. These themes were then organized in a thematic analysis network (Attride-Stirling, 2001; Braun & Clarke), illustrated in a diagram of the themes in a coherent manner (See Figure 1). The research team identified three major areas under which the themes clustered. These were: 1) Intrapersonal, which included cognitive and affective responses, reactions to the partner’s disclosure/discovery, impact upon the wife’s self-esteem, and the questioning of one’s sexual orientation; 2) Couple Relationship, including the process of disclosure/discovery, the MTF partners’ sensitivity to the wives’ feelings and experiences, their sexual relationship, a gradual process of transitioning, and renegotiation and boundary setting in their overall relationship; and 3) Family and Social Relationships, which involved sources of support and coping, relationships with immediate and extended family members, and disclosure to others, such as friends and co-workers/supervisors. Each of these areas is described below. These analyses and findings extend Erhardt’s presentation of these cases by focusing specifically on the transsexual cases and by conducting a formal qualitative thematic analysis that goes beyond some informal summary remarks in the conclusion of her book.

Rather than report on the specific numbers for each theme or sub-theme the method we chose to present the findings was to divide the numerical values into ranges that could be described with words so that the research report would reflect the qualitative nature of the study and flow smoothly. The ranges chosen were: 11-13—Most; 7-10—Many; 4-6—Several; 2-3—Few/Some; 1—One.

Findings

Intrapersonal Level

The main theme of the Interpersonal Level has to do with internal processes for the wives. These include emotional and cognitive processes. Wives’ narratives also spoke to the impact of their partners’ gender identity upon self-esteem and questions that arose for many about their own sexual orientation.

Emotional Responses. A wide range of emotional responses for the wives was evident in the stories of these couples. In the early stages of learning about their transgender partners many wives expressed feelings of shock, resentment, and anger. One wife “resented having an unwanted secret and its results, such as not being able to welcome our children to jump into bed with us... because daddy was wearing a nighty” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 192). Erhardt comments that those who are not told of their partner’s gender variance early in the relationship commonly experience “shock, disbelief, revulsion, fear, shame, and a sense of betrayal, and once the initial shock wears off, hurt, rage, fear, anxiety, shame, and a sense of abandonment may prevail” (p. 207). Some wives were fearful about violence occurring against their families and feared how families and friends would react to their partner's new gender identity.

Some wives likened their emotional process to that of grief and loss, and experienced stages similar to those identified by Kubler-Ross (1969), such as shock, numbness, denial, anger, and sadness. Several experienced depression, at least for a time. Others expressed that after the initial revelation, they experienced being on an “emotional rollercoaster” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 129). Some encouraged their partners to cross dress and transition, and were pleased to see their partners happier and being more true to themselves. After the initial emotional reactions of the wives, those who stayed were often are able to move from acquiescence to a place of tolerance, and ultimately many fully accept their MTF partner.

Cognitive Responses. The wives profiled in Erhardt’s (2007) book also displayed a range of cognitive responses. Almost all of the wives expressed some initial confusion or worries upon learning of their partner’s gender variance. Most of them worried about the reactions of others, wondered what their marriage would look like in the future, and questioned their own sexual orientation. Overall, the wives’ stories as told by Erhardt give a glimpse into a range of thought patterns reflecting worry, fearful thoughts, confusion, and eventually tolerance/acceptance. Most were concerned with what others might think and how the community would perceive them. Some women worried about their jobs and a few believed they were in physical danger. Many wives had to adapt to the loss of a traditional marriage and were unsure of how to create a new model. A lack of good models contributed to the confusion experienced by almost all of the women in understanding their partner’s gender issues. Most women did not fully understand the implications of their partner’s gender variance and believed cross-dressing was only a phase. For example, one mistakenly thought “that dressing up in women’s clothes was all that he would need to do to make him happy—that and my love and support” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 136). One wife lost respect for her MTF partner and did not believe the gender confusion was a serious issue.

After the initial confusion and adjustments, nearly every wife considered existential dilemmas and their self-reflections led to their becoming more self-aware. Learning of the MTF partner’s gender identity prompted almost all of the women to reflect upon their beliefs on the meanings of love, companionship, and intimacy. Some women considered their partners to be courageous for sharing their gender variance and a few women used humor to help cope with the changes. Almost all of the women made conscious decisions to be receptive to their partner’s needs and remain open to new experiences. For example, one wife tries “not be resentful, seeing it as just like a...medical catastrophe” that other couples might face (Erhardt, 2007, p. 132). Many of the women said they experienced profound personal growth and some said they now lead richer lives.

Impact on Wife’s Self-Esteem. Many wives spoke about the discovery or revelation of their MTF partner’s transgender identity as being a blow to their self-esteem. For some this was temporary and for others it was more persistent. One reported her self-esteem was “none, zilch, zip, nada!” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 132), while another noted she felt as if she had depended upon her partner for her self-esteem and had “gone back to feeling like a stupid, ugly, fat failure” (Erhardt, p. 125). Likewise, others reported their self-esteem as women being tied to the man in their lives, so the transitioning and lack of a man greatly impacted self-esteem. A few reported a history of chronic low self-esteem, which was exacerbated by transgender issues. Some blamed themselves, wondering if they could have done more or loved more to prevent their partner’s changing gender identity. Others experienced feeling threatened by or jealous of their partner’s newfound femininity and of their partner getting compliments about her feminine appearance. It seemed as though some wives called into question their own femininity in comparison to their partners’.

For some, the impact on self-esteem was influenced by a history of childhood sexual abuse, previous traumas, or life cycle issues coinciding with the coming out of their partner as transsexual. For one wife, the disclosure of her MTF partner’s gender identity coincided with her own menopause, and she noted that the issues associated with menopause, such as her changing status as a woman and mood swings, made it more challenging to cope with the revelation. The death of one wife’s mother occurred around the same time as her MTF partner’s disclosure, and she noted, “grieving the loss of my mother and my husband as I had known him, dealing with the cross-dressing...was a struggle that kept getting more difficult” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 113).

While many wives described initial challenges to their self-esteem and identity, many worked through these issues and used the experience to do some soul searching and redefining of themselves. Several noted it was helpful to establish their own personal goals, which helped their self-esteem and image strengthen over time.

Questioning Sexual Identity/Orientation. The changing nature of their partner’s gender identity led many wives to question their own sexual identity or orientation. Many of the wives experienced personal struggles with their own sexual identity. For a few of them, their partners’ gender transitions and struggles with sexual orientation lead them to question or challenge their own sexual orientation. Many wondered what the implications were for being attracted to their MTF partners as women. The wives who began to wonder if they too were gay or bisexual often tested themselves by looking at other women and attempting to view them in a sexual way. Of all the women who engaged in this behavior, none of them reported finding other women arousing. One woman reported that she alone had not pondered the issue of her own sexual orientation, but was prompted to when asked by her therapist if she was bisexual. This led to questioning by the woman, but she ultimately identified as heterosexual. One wife stated, “I didn’t have any internal strife about what it might mean about my own sexual orientation. In bed I was just reacting, and the experience was positive” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 170). Several resisted being labeled in terms of their sexual orientation, and described their attraction toward their individual partner, suggesting an orientation toward a specific person rather than to an entire gender.

Questioning one’s sexual orientation was not limited to only those wives who identified as heterosexual. In a couple of the cases, the wife identified as bisexual well before her MTF partner’s transition. For these bisexual women, they still questioned their own sexuality. One noted that, ultimately, there was an improvement in relating sexually to her partner and determined that they were in love regardless of appearances. The bisexual wives seemed to have an overall more relaxed and accepting view of their partners’ transitions and changing gender identity.

Couple Relationship

The main theme of the Couple Relationship deals with key dynamics in the dyad of the couple relationship. Sub-themes in this area include the nature of the discovery or disclosure of the MTF’s gender identity, the transgender partner’s sensitivity and understanding of the wife’s experiences, and the couple’s sexual relationship. Couples also dealt with the gradual nature of the transition and renegotiated boundaries as the gender transition evolved.

Discovery/Disclosure. The way in which the wife became aware of her partner’s gender identity can be grouped into two categories: self-disclosure or accidental discovery. In a large majority of cases reviewed, the MTF partner disclosed the gender variance to the natal female partner. Accidental discovery by the natal female occurred in only a few of the cases reviewed. Further exploration into these two categories reveals additional variety.

Regarding self-disclosure, some of the men tried to explain their gender dysphoria before marriage while others had been married several years before discussing their confusion. In about half of the cases, disclosure occurred while the couple was dating. Most of these disclosures took place in a casual setting, such as over dinner or during some other outing. The women who were told were generally supportive, yet confused. Most admit to not fully understanding the depth of their partner’s gender variance. The natal men who disclosed their gender identity after marriage had been married an average of six years, while one had been married 31 years before fully discussing the gender identity. As opposed to the casual nature of disclosure among the dating couples, discussing gender variance was a more serious and formal topic for the married couples. One wife related, “[He] told me that he had felt all his life that he was really female... [and] begged me to forgive him for having misled me” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 161). Common to all self-disclosures was a gradual progression from identification as a cross-dresser to identification as a transsexual.

Examination of the cases where the transwoman’s gender variance was accidentally discovered also reveals variety. In one instance, guilt and embarrassment led the MTF partner to set up a scenario in order to be caught, rather than bring up the subject directly. For the other couples, the discovery of female attire and makeup belonging to the transwoman precipitated discussion of her gender identity issues. One wife was suspicious of her MTF partner’s actions and searched personal belongings and the house for evidence of an affair, while another wife accidentally found her partner’s makeup. For these couples, the discovery event was disturbing and was accompanied by more distress compared to the reactions of the women whose partners had self-disclosed.

Transwomen’s Sensitivity & Understanding of Wife’s Feelings & Experience. In addition to how the MTF partner’s gender identity was revealed or discovered, another key theme to emerge that seemed to impact wives’ experiences was the transwoman’s sensitivity to the wife’s feelings and an appreciation for the adjustments involved with this redefining experience. Wives expressed a need to share decisions about the pace of the transition, not feel pushed, and typically to take the transition slowly. Wives needed to be understood and for their MTF partners to empathize with their feelings. In some cases this stance ran counter to the transgender partner’s excitement to pursue what had been anticipated for some time. Wives reported some acknowledgement by their transitioning partners that the transition was “changing the rules” and that this was “not what she had signed on for;” yet, some wives did not believe their partners really “got it.” Others felt supported by their transsexual partners and the couple shared feelings openly.

Some transwomen were inattentive to their wives’ needs, such as the wives’ needs to feel desired and to be involved in transitioning decisions; thus, making the transition more difficult for the wives. Some wives complained about unilateral decisions by their transsexual partner. For example, one transwoman revealed her gender identity to co-workers without the wife’s knowledge, eroding trust in their relationship and leaving the wife feeling little control in the process. Several wives spoke about the central position their partner’s transitioning took in the relationship, with everything seeming to revolve around the transwoman’s emerging gender identity, leaving little room for the wives’ range of emotions. Some felt as if their transsexual partner was “self-centered” and was going through a self-indulgent second adolescence. Alternatively, some MTF partners tempered their own joy and excitement out of sensitivity to their wives, and recognized that wives were greatly impacted by their gender transitioning.

Sexual Relationship. For the majority of the couples interviewed by Erhardt (2007), there was a change noted in their sexual relationship. Many of the transgender partners took female hormones as a component of their transition process, noticeably impacting their libidos. For most, this impact resulted in a decreased sex drive, or, for others, a complete lack of desire for sex. Many of the couples now have celibate relationships, which has lead to frustration for some, but a comfortable situation for others. Some couples saw celibacy as a necessary step for staying in the relationship, as was the case with one wife, who shared, “We chose to give up our sex life and stay in our relationship as ‘soul mates,’ since we had established a very special, comfortable relationship that neither was willing to give up” (Erhardt,p.151).

Several of the wives, regardless of their own sexual orientation, voiced concerns that their partners would begin to desire other people, specifically men. This concern was validated for some, as a few of the transsexual partners did express feelings of attraction towards men.

A couple of the natal females expressed hope for their sexual relationship with their partners, and willingness to be flexible on the terms of the relationship. One explained, “Now we have entered a new phase of our relationship. We can’t have the sexual relationship I crave on my terms, so we must redefine the terms. I’m looking at intimacy in a new way. Intimacy is what two people make it” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 159).

Gradual Identity Transition. The most important trend to note in the process of identity transition for the transsexual partners is the gradual nature of the change. While some altered the speed or nature of their transitions to accommodate the comfort levels of the natal female partner, most reported that changes seemed to build upon one another. For a few of the transsexual partners, their gender identity issues began in childhood. One described feeling different since nine years old, while one transwoman’s gender identity could be traced back even further, “He told me that he remembered having dressed in women’s clothes since kindergarten, and that he had suffered pain, guilt, shame, and self-exile for as long as he could remember” (Erhardt, 2007, p.161).

For most of the MTF partners, their female identity experimentation began with cross-dressing. The gradual nature of transitioning is embodied in this fact, as many would cross-dress in the privacy of their homes, but present as males in public, until building up the confidence to present as female full-time.

Nearly all of the transsexual partners had engaged in some type of feminizing procedure, though some were against any type of treatment or changes. These procedures included growing out hair and nails, having facial or body electrolysis, taking hormones or testosterone blockers and having breast implants or feminizing facial surgery. The final stages of physical transformation for many of the transsexual partners involved sexual reassignment surgery (SRS). While some were still in the stages of considering or planning for surgery, most had engaged in SRS procedures. Most of the participants currently identify as transsexual, while one described herself being biologically male, but wired with a female brain. In addition to the physical changes made, some transsexuals also had their names legally changed.

The identity transition of the transsexual partners was not easy on the natal female partner, as a number of them discussed being threatened by their partner’s newfound femininity. This was especially true regarding the attention the transsexual partner received, from other men, other women, or, in some cases, from salespeople while shopping. Conversely, some couples reported that they enjoyed the identity transition process and their relationship was growing stronger as a result. As one wife reported, “In terms of the transition process, and decisions we will make as we get further into it, we have made a conscious, joint decision to remain open-minded and not to overly prescribe the outcome” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 146).

Renegotiation and Setting Boundaries. Another dynamic for several couples involved the setting of boundaries around the transwoman’s femme presentation and negotiating issues such as finances, physical space, and gender roles. For example, one wife stated, “While the kids were around, Gregg was still Gregg. Only while they were at school could Gregg become Linda” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 182). In addition to placing boundaries around sharing information with children, others had limits about whether or how they might present in public as a couple with the MTF partner dressed in femme. Other wives expressed a need for limits in the bedroom, and some were uncomfortable with their partners cross-dressing as part of their sexual activities. For many, placing such limits and taking small steps allowed wives to feel more comfortable with their partners’ new gender identity.

Some wives expressed having money issues, with their spouses wanting to purge old wardrobes, buy new clothes or makeup, and receive feminizing procedures. Turf and physical space issues arose for some around topics such as sharing of clothes, use of bathrooms and make-up, and staking out certain areas of the home, such as “my kitchen” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 197). One couple, who functioned more as friends and roommates, negotiated separate bedrooms and bathrooms.

Shifts in gender roles and power dynamics were seen in some cases, wherein some wives felt as if they had to take on more stereotypical male roles and assume more traditional masculine duties around the home. One wife stated, “In my marriage, I play the role of the traditional husband, and my male-to-female transsexual spouse plays the role of the wife” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 179).

Family and Social Relationships

The final main theme of Family and Social Relationships extends beyond the couple dyad to include relationships with children, extended family members, friends, and others. Sub-themes include family support, disclosure of the transgender identity to others and sources of support and coping.

Family Support. Family support for the couples profiled in Erhardt’s (2007) book is varied. While the majority of couples received at least partial support from their families, one couple was rejected by their family, and two others have kept their gender identity a secret. In all cases, the couple’s children were more likely to be supportive than extended family, and younger children are more accepting than adult children. Fathers were generally slower to accept their son’s transitioning, and in some cases this was made more difficult if the transwoman was an only son. Although the father of one MTF transsexual gradually accepted his son's new gender identity, he at one point stated, “that out of five kids, only one was male, and now it looks like even that Y chromosome didn't take!” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 145). Closer examination of family support reveals a range of reactions.

Of the couples who received some support from family, about half were totally accepted. All of the couples who received total support had young children or grandchildren who accepted and supported the changes. These couples reported being surprised at how easily the youngsters adapted to the change of their father or grandfather and the subsequent feelings of relief from no longer hiding secrets. One couple’s teenage sons, “showed a great deal of compassion for their dad...[and] knew that he would always be there for them no matter what his outer appearance might be” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 130). After telling her sons, this wife “was surprised that telling our children gave me a feeling of relief. No more lies, and I no longer had to hide my feelings” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 130). Most of these couples were also surprised at the support their children received from classmates and school personnel who were aware of the changing family dynamics.

While some couples received total family support, others received mixed support. Most of these couples had adult children and large extended families. It was common for some of the children to accept their father’s changes and some siblings and cousins were accepting while others were uncomfortable with the cross-dressing or transsexualism. All of the couples who received partial support deliberately chose those extended family members whom they would tell. Also common to the couples receiving partial support was acceptance that grew over time. In one case, family support changed over a decade from cut-off to almost total acceptance.

Although most couples in Erhardt’s book had some family support, three couples were not supported by their families. One couple was rejected by extended family after the transwoman discussed her gender variance with her mother and sister. Their reaction prompted the couple to stop coming out to other family and friends. In the other two cases, the couples decided their extended family would not understand and kept their gender identity issues private. For one of these couples, the wife knows her two adult sons are aware of their father’s cross-dressing but they refuse to discuss it. Common to the secret-keeping couples, hiding the truth was a burden and an added source of stress.

Disclosure to Others. Another important area noted in these stories involved disclosing the MTF partner’s gender identity to others outside the family. This typically involved the workplace, friends, and religious organizations. This was an area over which many wives chose to exert some control and as noted above, when MTF partners disclosed to others without the wife’s knowledge or consent, trust suffered in the relationship. Disclosure to work supervisors and co-workers was generally done cautiously, often after testing the waters and becoming aware of policies related to gender identity discrimination. Many wives worried about a loss of income or loss of their MTF partner’s employment that might be associated with workplace disclosure. In one case, the transsexual partner was self-employed and found that her business was the first place she began to present as a woman.

Reactions from friends varied, with some being supportive, while others expressed support but remained more distant. Some friendships ended as a result of the revelation, and some wives spoke of the pain of losing close friendships. As was true for the emerging identity of the transsexual partner, and of the wife’s need to pace the transition process, disclosing to others typically occurred gradually. For example, one MTF started by cross dressing on the deck, then worked her way down the driveway, and eventually progressed to the store, work, and attending daily activities. Being selective about who was told and disclosing to those who were most likely to be supportive were common. One wife preferred to live secretly in a “stealth mode” (Erhardt, 2007, p. 164). Since not all family and friends were supportive of the gender transition, some couples turned to support groups and transgender communities. Through these organizations, many couples gained new friends and met others in similar situations.

Support/Coping. Several helpful means of support and coping strategies were identified by the wives. Some wives attended transgender conferences (e.g., Southern Comfort, SPICE) or participated in on-line chat rooms along with their transsexual partners. Several had mostly supportive family and friends and derived considerable support from the transgender community. Most did reading about transgenderism. Many participated in online and local support groups, such as PFLAG, and more specific transgender support groups such as Transfamily and Tri-Ess. One couple shared that since joining their support groups, they were able to “act like their true selves” and gained insight about themselves, their relationship, and concerns. Individual and/or couple therapy were used by many. Church was a source of support and acceptance for some, though even churches that had affirmative gay and lesbian programs typically did not have specific transgender supports.

Coping strategies employed by the wives included journaling, poetry, talking with friends and family members, and maintaining a good sense of humor. Interestingly, shopping together was mentioned by several as a new couple activity, and some found this to be a bonus that could be shared with their transitioning partner who had showed little interest in shopping previously. While many wives found support in family and friends, some friends and family members were not supportive, and became distant or in some cases, relationships were cut off. A couple wives found little support from others and remained very socially isolated.

Discussions and Implications

The narratives presented in Erhardt’s book (2007) provide keen insights into the experiences of wives who stay with transsexual partners. This study identified key elements of those experiences regarding intrapersonal dynamics, couple relationships, and family and other social relationships. While the major life transition for this unique form of couple does not come without challenges, it is inspiring to learn of their ability to work through these issues and strengthen their relationships. The findings from this exploration add to the limited but growing literature that addresses couple and family relationships of transgender individuals.

The study endeavored to identify the key elements of the experiences of wives who stay with their MTF transsexual partners, with particular attention to the psychological and relational aspects of these wives’ experiences. Findings from this study are consistent with several of the factors identified by Samons (2009) as important for couple therapy with MTF transsexuals and their partners. For example, the finding that a common reaction for wives is that “this was not what they signed on for” is similar to Samons’ point that the wife often feels as if the rules have changed and various issues may need to be negotiated, also noted in the findings of this study. Samons also notes the importance of communication skills and sensitivity of the transsexual partner for the wife’s feelings, both important findings from this study. Consistent with other literature (Coolhart, 2007; Israel, 2004, 2005, Zamboni, 2006), the current study supports the notion that while there are often significant issues to work through, with commitment and open communication, couples can negotiate this major transition and as a result strengthen their relationships.

The first author is currently conducting a study of couples with at least one transsexual partner. This qualitative study includes both MTF and FTM transsexuals and explores the perspectives of both partners. While preliminary, the initial findings from this ongoing study are consistent with those presented above, especially for those couples who were married/partnered pre-transition. The significance of the discovery/disclosure process, typical emotional and cognitive responses of the non-transgender partner, pacing and negotiation of the transition and disclosure to others, and maintaining a perspective on the overall relationship are consistent themes across the two studies.

The findings from the current study also might be considered in light of Lev’s (2004) Family Emergence stages that address typical stages of adjustment for the partners and family members of transgender persons. The four stages are: 1) Discovery & Disclosure, 2) Turmoil, 3) Negotiation, and 4) Finding Balance. Considering the summary of the themes and sub-themes in Figure 1, one can note the similarity in language between at least two of Lev’s stages, Discovery & Disclosure and Negotiation, and key themes from this study, Discovery/Disclosure and Renegotiation and Setting Boundaries. Many of the intense emotional and cognitive responses and the impact upon the wife’s self esteem fit well in Lev’s Turmoil stage. Lev’s Finding Balance stage is reflected in findings from this current study about how the relationship can be maintained and strengthened and personal growth can take place for both partners.

A limitation of this investigation is that it relied upon published narratives. Future studies might develop specific research questions and gather data directly from couples and families using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Erhardt’s (2007) narratives are limited to the wife’s perspective, which is commendable given the previous lack of attention in the professional literature to the partners of transsexuals. Future inquiries would do well to include both partners’ perspectives and also to explore the impact of gender transitioning on children and extended family relationships. Erhardt does not report on the race or ethnicity of the women in her book, but future work is encouraged to address race and ethnicity and might intentionally study racial or ethnic minority transsexuals and partners, who face multiple minority status. Finally, this study only considered MTF transsexuals. Much less is written about FTM transsexuals, particularly about their remaining in committed relationships through the transition process, yet this warrants further exploration.

Implications for Helping Professionals

Helping professionals who work with couples or families should gain knowledge about this unique form of couple. Clinicians should be familiar with the latest version of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association’s Standards of Care that have been developed for gender identity disorders and serve as guidelines for determining readiness for hormonal treatment or SRS (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2001). Normalizing the gradual process of the evolution of the transsexual partner’s gender identity is recommended, as many move through cross-dressing to identifying as a MTF transsexual to actual transitioning. It would be helpful to create space and validation for a range of emotions for both partners, which at times may be quite different. For example, the transsexual partner may be feeling exhilarated and free, whereas the other partner may feel overwhelmed and depressed. Samons (2009) identifies a “flood stage” during which, after a long period of suppression, MTF partners feel as if they can never spend enough time in femme and may be self-focused and not think through the implications of their transition plans on the marriage.

Helping the couple negotiate the timing of transitional steps and decide when to inform children, extended family, friends, or others are valuable services a helping professional could provide. An emphasis should be placed upon shared decision-making and respect for the views of all involved. Given the need for the wife to feel some control over the process and to take into consideration the range of feelings of both partners, one should advise against unilateral transitioning or disclosure decisions by the transsexual partner. Indeed, Samons (2009, p. 157) emphasizes, “[The wife] will need time to come to terms with changes this means for her own life. When she is allowed this time, she may be able to make peace with it.” It would also be helpful to normalize the wife’s questioning of her own sexual identity or sexual orientation and the feelings associated with the choice of a partner who identifies as transsexual. Facilitating candid discussion of the couple’s physical and sexual intimacy and allowing for a range of possible outcomes for the couple is also recommended.

A systemic perspective can be useful in order to assess and intervene to support the relationship if the partners desire to stay together. The use of genograms, assessment of immediate and extended family relationship dynamics and other support networks, evaluation of the relationship quality overall and the timing and nature of the discovery/revelation, and inquiring about the role of religion or spirituality can all be valuable in gathering a complete picture and identifying constraints and sources of strength for the couple (Coolhart, 2007; Samons, 2009)

The experiences of many of the couples in Erhardt’s (2007) book suggest the value of the use of support groups and online networks, especially early on in the process. According to Samons (2009), these supports can:

help him take a clear look at the reality of his gender identity and the costs and benefits of the various ways of living with it, ...and for the wife, finding that she is not alone and having the support and role modeling of other wives who have chosen to stay in transgender marriages can be life altering. (p. 161)

Many of these couples spoke about the strength of their friendship, even when the sexual part of their relationship became less important. Focusing upon nurturing the marital friendship is advised and one could draw on the work of Gottman and colleagues (1999; 2006) for strategies. The transsexual partner’s emerging identity and transitioning process can become a central focus for the couple. It is important to keep this in perspective, and celebrate other areas of strength for the couple and family so that the transition process is not overshadowing everything else. The non-transgender partner should be encouraged to explore avenues for personal growth and self-development, as several wives in this study found that to be helpful. Helping professionals can find a healthy balance between providing support for potential challenges and instilling hope that couples are able to navigate this major transition and can become closer and grow together in the process.

References

Association for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Issues in Counseling (2009). Competencies for counseling with transgender clients. Alexandria, VA: Author. (available at:[http://www.algbtic.org])

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1, 385-405.

Bockting, W. O., Knudson, G., & Goldberg, J. M. (2007). Counseling and mental health care for transgender adults and loved ones. International Journal of Transgenderism, 9(3), 35-82.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Cohen, H. L., Padilla, Y. C., & Aravena, V. C. (2006). Psychosocial support for families of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. In D. F. Morrow & L. Messinger (Eds.) Sexual orientation and gender expression in social work practice: Working with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people (pp. 262-283). New York: Columbia University Press.

Coolhart, D. (2007, May/June). Transgender in family therapy. Family Therapy Magazine, 36-42.

Coolhart, D., Provancher, N., Hager., & Wang, M-N. (2008). Recommending transsexual clients for gender transition: A therapeutic tool for assessing readiness. Journal of GBLT Family Studies, 4(3), 301-324.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Erhardt, V. (2007). Head over heels: Wives who stay with cross-dressers and transsexuals. New York: Haworth Press.

Girshick, L. (2008). Transgender voices: Beyond women and men. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

Gottman, J. M., Gottman, J. S., & DeClaire, J. (2006). 10 lessons to transform your marriage. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Gottman, J., & Silver, N. (1999). The seven principles for making marriage work. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Israel, G. E., (2004). Supporting transgender and sex reassignment issues: Couple and family dynamics. In J. J. Bigner& J. L. Wetchler (Eds.), Relationship therapy with same-sex couples (pp. 53-63). New York: Haworth Press.

Israel, G. E. (2005). Translove: Transgender persons and their families. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 1, 53-67.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

Lev, A. I. (2004). Transgender emergence: Therapeutic guidelines for working with gender variant people and their families. New York: Haworth Clinical Practice Press.

Malpas, J. (2006). From otherness to alliance: Transgender couples in therapy. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 2(3/4), 183-206.

Nuttbrock, L., A, Bockting, W., Hwahng, S., Rosenblum, A., Mason, M, Macri, M, & Becker, J. (2009). Gender identity affirmation among male-to-female transgender persons: A life course analysis across types of relationships and cultural/lifestyle factors. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 24, 108-125.

Raj, R. (2008). Transforming couples and families: A trans-formative therapeutic model for working with the loved-ones of gender-divergent youth and trans-identified adults. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 4(2), 133-163.

Samons, S.L. (2009). Can this marriage be saved? Addressing male-to-female transgender issues in couples therapy. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 24, 152-162.

White, T., & Ettner, R. (2004). Disclosure, risks, and protective factors for children whose parents are undergoing a gender transition. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 8, 129-145.

World Professional Association for Transgender Health (2001). The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association’s Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders, Sixth version. Retrieved from:[http://www.wpath.org/]

Zamboni, B.D. (2006). Therapeutic considerations in working with the family, friends, and partners of transgendered individuals. Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 14, 174-179.