The Context of Rural Economic Stress in Families with Children

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Rural communities face a unique set of constraints when supporting families and children in need. This article describes a study of childhood contexts characterized by economic and parental stress, uncertain support systems, and a shifting community environment defined by rural restructuring. Suggestions are made regarding the "fit" of public policy and community services with family diversity.

Key words: poverty, school readiness, welfare, children, families, reading accuracy

David R. Imig, Ph.D., is Professor, Department of Family and Child Ecology, 203E Human Ecology Building, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 48824-1030. Electronic mail may be sent via Internet to [email protected].

All authors are affiliated with Michigan State University. We wish to acknowledge the significant contributions made by Professor Anne Soderman, and doctoral students Barbara Wells and Patty Gross.

Poverty represents a significant loss of actual and potential human and social capital to any community. Policies designed to ameliorate poverty must be targeted to specific cohorts and take into account their differing contexts and histories. Poverty often is a transitory problem with people experiencing spells of poverty amidst periods of recovery (Bane & Ellwood 1986; Duncan, 1984). The few longitudinal studies of poverty suggest that persistent, long-term poverty is more common among rural residents, blacks, elderly, children, and family members living with female householders or with household heads without a high school education (Deavers & Hoppe, 1992).

Rural restructuring has spelled economic distress for a growing proportion of rural American children and their families. Rural restructuring has tightened job opportunities and lowered income, benefits, and hours of work for rural women—which explains in part why having a single mother poses a greater risk for poverty for rural children (Wenk & Hardesty, 1993; Garrett, An'andu, & Ferron, 1994). For rural children the likelihood of living in poverty is quite high. In 1990, 22.9% of rural children lived in poverty compared to 20% of urban children—a substantial increase since 1973 when the rural childhood poverty rate stood at 16.6% (Sherman, 1992). Past studies suggested that the key factors accounting for this increasing vulnerability and poverty for children are a general decline in wages and real income, a decline in the effectiveness of government programs, and an increase in single parent families—particularly female-headed households (Sherman, 1992; Jensen & Eggebeen, 1992; Voydanoff, 1990).

The purpose of this study was to better understand the circumstances, contexts, and experiences of rural children and their families living in poverty. The community context and scope of the project, its design, methodology, and selected findings related to economic stress, school readiness, rural children, and their families will be described in this article. The study utilized a multi-modal methodology designed to access multi-level community data and perceptions of the experiences of children.

The Context of Rural Economic Stress

Given equivalent education, wages for rural workers are lower than for urban workers. Lower educational attainment among rural populations has compounded the problem and has been linked to the evolution of a low-wage rural manufacturing industry (Deavers & Hoppe, 1992; Adams & Duncan, 1992). Rural people with lower levels of education face a far greater risk of poverty than do others. They have higher rates of unemployment, underemployment, and longer spells of poverty (Lichter, Cornwell, & Eggebeen, 1993; Lichter & Eggebeen, 1993).

Economic pressure from low income and high debt has been theoretically and empirically linked to psychological distress. Types of psychological distress found among rural poor adults include depression, anxiety, lack of motivation, and dejection (Lorenz, Conger, Montague, & Wickrama, 1993; Voydanoff, 1990). Level of poverty is a direct indicator of quality of life and—for children and youth—is related directly to developmental discrepancy, school failure, unemployability, substance abuse, crime, and psychological problems such as depression and low self esteem. Poverty has been found to foster chronic stress and poor mental health among families. Poor children are more likely to have reported behavior and conduct problems, low self esteem, and emotional problems. The absence of hope or prospects for economic improvement deepen the emotional costs of poverty (Huston, 1991).

The Negotiation of a Community-University Research Partnership

Initially, this project was titled a study of rural poverty. But the involved communities did not perceive themselves or—more importantly—did not wish to be labeled as places of poverty. Therefore, a shared vision around which to construct the project and gain entrance into the community had to be identified and negotiated. The establishment of this university-community partnership relied on a facilitator known to both the university and community—the Land Grant Cooperative Extension Service (CES). The investigators contacted the county CES staff, introduced the "vision" of the project, and asked if they would be interested in being involved. The CES staff agreed to bring the prospective partners together to determine if there was the potential for future collaboration.

The project team was invited to a community meeting focusing on the needs of children and families. While community members were pleased that there was a large proportion of students entering their educational system with exceptional skills and good health, their concern focused on a growing proportion of children arriving at school unprepared to begin their education. These children did not have the demonstrated skills and abilities that are more commonly referred to as "school readiness" (Boyer, 1993). In addition, community leaders were also concerned about the absence of affordable child care, recreation, availability of social services, and—paradoxically—the low level of utilization of available social services for children among some families in need. Subsequently, school readiness was among those community needs given highest priority. The project researchers agreed that the study of school readiness was an important research objective and reasoned that it would be a conceptually important proxy for poverty and a strategic entrance-point into the community.

Obviously, partners in any relationship are interested in establishing a quid pro quo (something for something). The researchers wanted community access and cooperation. The community leaders expressed a desire to understand and improve school readiness and to demonstrate to the community that they, their representatives, "could deliver." The project agreed with the community leaders to assess the reading levels of all first graders in the school system, to identify a faculty member skilled in reading assessment, to conduct and pay for the actual assessment, and to conduct support training for school teachers and staff. The community representatives agreed to cooperate with the project to accomplish its objectives. The project involved and employed community residents when and where possible.

SCOPE AND DESIGN OF THE STUDY

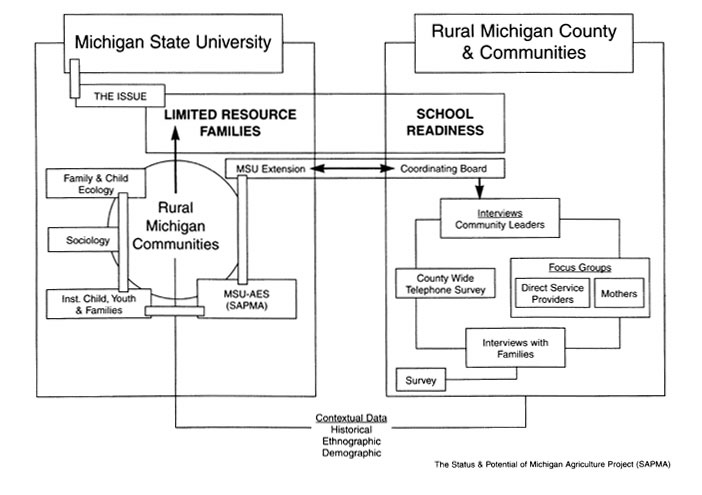

This project represented a unique collaboration of institutional, community, and family partners. Involved were two academic departments (Family and Child Ecology; Sociology), two university institutes (Institute for Children, Youth and Families; Institute for Public Policy and Social Research), one research unit (Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station), one outreach unit (MSU Extension), an academic unit from a local university, 17 community agencies and selected staff, and numerous families (see Figure 1).

SAMPLE DEMOGRAPHICS

Of the 30 families who were interviewed, 24 were currently married (16 first marriages, 8 remarriages), 3 were divorced, 1 was widowed, and 2 were separated. For the 16 first marriages, the length of marriage was 10.9 years, and for the 8 remarriages was 6.0 years. The average age of both adult males and females was 34 to 35 years. The adult females, on average, had completed 12.45 years of school; and the males had completed 12.91 years of school. Mean total family income ranged from $25,000 to $30,000. Sixteen of the adult females were employed full-time, working 36 to 37 hours per week and averaging approximately $10.00 per hour. Of the remaining 14 adult females, 3 worked part-time, 3 were unemployed, 7 stayed at home full-time, and 1 was disabled. Twenty-two of the adult male spouses/partners were employed full-time, working 42 to 43 hours per week and averaging $11.00 to $12.00 per hour. Two were employed part-time (28.5 hours per week; $6.00 per hour). Of the 30 families in this phase of the study, 5 families were classified as farm families.

Stress and Poverty

Rural mothers' lives are characterized by high levels of stress—economic, personal, social, and familial. In the focus groups and interviews, the mothers and service providers identified patterns which indicated that everyday experiences were a struggle. These are the hidden injuries of class. The many ways that subjects' everyday experiences differed from middle-class experiences provides a rich description of how economic restructuring is debilitating to families:

- "My husband has got a job making five bucks an hour. And that's it. He is working 50 to 60 hours a week, plus we have food stamps and Medicaid, and so we are just sneaking by. Plus I've got grants and loans to go to school." —Married mother of two.

- "The guys they hunt all, you know, if there is hunting season, fishing season, they are out there doing it and it is not because it is just a sport, it is because that's how they keep their families fed. You know, that's, that's how you make sure there is meat on the table and fresh vegetables." —Single mother of two.

- "I hold four jobs right now, two full times and two part times." —Mother interviewed.

- "We have a home, we have five children, I baby sit part time, my husband works, he says he has four jobs." (She thinks he really has only three jobs.) —Mother interviewed.

These strategies are restricted by poor job prospects and depressed economic forecasts for employment in small rural communities. For the most part, the only perceived job opportunities are factories, and part-time service jobs in retail or eateries: "If you're looking for a full-time job, forget it, there aren't very many of them out there and if there is one open it's because you knew somebody that knew somebody that could get you in." This comment is consistent with recent labor market analyses indicating that four out of five new jobs in rural markets are in the service industry. The available full-time factory jobs are considered locally to be inappropriate for most women. They are dirty, require hard physical work, and require long hours. Yet the most limiting factor of factory jobs is the required overtime. These mothers have tenuous and expensive child-care situations that block their ability and flexibility to work overtime: "Most of them you have to work too many hours. I couldn't work there because I couldn't afford day care for the hours that I would have to be there because they are really busy."

The above issues all are related to restructuring as well as to the entrenched paternalistic employment in rural markets. Required overtime and part-time hours are both strategies used by employers to limit personnel costs in terms of benefits and income. Local business leaders present a contradictory stance. They criticize the local schools for failure to insure a strong pool of skilled workers and bemoan the out-migration of that labor, yet their local plants do not provide wages adequate to support young families and the social reproduction of young labor in rural areas. Women often feel fortunate to have jobs and lack a sense of capacity to insure a positive work experience. For example, a woman who works in a family-owned factory describes her situation: "Well, my problem is that most of the people I work with are men and ... it's rough when you have to deal with sexual harassment and things like that." Stress is exacerbated by the sense that as they try to improve their economic status through available employment options, the poor mothers perceive a necessary trade-off of sacrificing the quality of mothering through less time with children, lower quality of interaction, lack of supervision, and less time for domestic chores. One mother talked about how her studying to improve her employment opportunities impacted her child: "My son, my smallest, youngest son, he['s] having a lot of problems in the school and then like too, with me going to school all of the time, and coming home and studying, I have very little time to work with him, so, I just don't think he gets what he needs, develop the skills that he needs."

A common assumption is that rural poverty is not as serious as urban poverty because farms and farm families are somehow immune from poverty and that families can self-provision (Sherman, 1992). Rural restructuring in the agricultural industry has led to a higher rate of family poverty among farm families. In the rural school districts in this study, half the children from farms qualify for free or reduced school-lunch programs.

Household Strategies for Children's Needs

Interview questions explored how families went about meeting the needs of their children. We asked such questions as, "Do you ever find it hard to buy the things that your child needs?" and "How do you get things that your child wants?" One of the basic dilemmas reported by parents irrespective of income level was how to maintain a financial balance that differentiated needs and wants while taking into account financial constraints, household management, and the needs of other family members.

Some parents indicated that their children went without and that they did not buy for them if the money was not available: "If we don't have the money for it, ... we don't buy it." Other parents shifted money from other bills, borrowed money, or used credit to meet their children's needs: "I wish I could just go buy them but I can't. He needs shoes, let's see, well, if I skimp on this bill maybe we can get his shoes in 2 weeks and I can just make up the bill next month." A third general strategy was to sacrifice. A fourth was to set priorities, save for what you want, and when possible have a child use their own money. A fifth strategy was to seek out other resources such as the informal economy, social service programs, and overtime work, or to ask other parents for extra help.

A mother of three children who was currently receiving public assistance explained how she had to make hard choices. The issue for her was not between wants or needs, but which of their basic needs should a parent meet first: "Winter is coming on, I've got to have money for heat. Not having a phone is a problem. At this time I just can't afford even a phone bill as low as 40 bucks." This same mother later commented on social pressures that create desires and her feelings of anti-commercialism: "A lot of times we just have to tell the kids we can't afford it. You have to go without. You have to keep kids away from TV commercials, because they want to go to McDonald's every week or Burger King, because of the toys or whatever, and we just don't get a lot of wants. We don't go to movies, we wait for them to come out on video. We take advantage of the library." One mother commented on how she feels about these decisions: "I don't want to say I want my children to have the best, but I would like to be able to buy her better things than she has. You can buy the same amount of clothes, good quality clothes from K-Mart as you can from Hudson's. It is just more or less the name. I want to say that I buy the best that I can afford. That's what I try to tell my children. I can't help it what everybody else has, we buy what we can afford." Mothers are very aware of the social pressure to acquire material things. One mother felt that living in a rural area provided some protection from such pressures: "Material things don't mean so much. I think up here in a rural area people might not have the best jobs, or drive the best cars. If you walk through that trailer park, that is a perfect example of how half of the kids that my children go to school with live. We don't have the best clothes, we don't have the best of everything, but most of the time basically everybody is happy. Because we don't have the pressure of hurry up and buy this, buy that. You know."

Parenting and School Readiness

An important focus of this project was to study the capacity of rural children to successfully engage in formal education. School readiness requires a home context and parental interaction that serve to nurture the developmental potentials of children and establish the skills necessary to effectively participate in formal learning processes. Equally critical are schools that are ready for the children—irrespective of the child's developmental status.

THE FOUR PARADIGMS OF PARENTING

It is not particularly profound to suggest that families parent differently. The challenge for professionals is to develop models of parenting that recognize the core differences of parenting styles and allow for respondents to describe their unique stylistic configurations. The scale used in this study to assess parenting style was a modified version of the Family Regime Assessment Scale - FRAS (Imig & Phillips, 1992). This scale, based on the works of Kantor and Lehr (1975) and Constantine (1986), identifies four epistemological approaches to parenting: Closed, Random, Open, and Synchronous. The Closed family system is group-oriented, hierarchially structured, normatively traditional, uses reward-punishment sanction strategies, is dominated by constancy feedback and strategies designed to maintain continuity, resist change, achieve closure, and maintain the status quo. The Random family fosters individuality, autonomy, and independence. Exploratory in character, this laterally structured system emphasizes strategies incorporating variety feedback and spontaneity intended to facilitate and capitalize on the dynamics of change. The Open family requires equality among family members which integrates individual and group interests. The open system synthesizes constancy and variety feedback to achieve an evolving and emerging state of fluid adaptability integrating the past, present, and future. In the Synchronous family system, the rules and truth emerge from timeless processes implicitly embedded in the integration of experience, context, and environment. Although each system member may select a different path, they all ultimately converge and arrive at the same understandings, insights, and ways of knowing.

PARENTING STYLES

When considering global parenting styles, the majority of the 28 families parented using a predominately Open (N=15) or Open related style (N=9). Of the remaining four families, three families manifested divergent parenting styles (one Random, one Closed, one Synchronous), and a Closed-Random combination completed the sample. The parents of farm versus non-farm children were notably similar. The vast majority of all parents in the sample tended to favor a form of parent-child interaction characterized by discussion, adaptability, flexibility, and agreement; and—if anything—these Open-styled parenting attributes were most typified by farm families.

All parents tended to emphasize the importance of hard work and to value and respect the possessions and belongings that may be acquired because of such efforts. Parents emphasized the importance of using and scheduling time in a flexible and adaptable manner, being caring to each other in a genuine and playful manner, and believed that most anything was possible when the family, valuing personal strengths, worked together as a group. Among the more subtle distinctions were that farm families were distinguished from non-farm families (a) by their emphasis on getting important things done through discussion and agreement rather than by telling their children what to do; (b) by emphasizing the importance of observing and listening as a way of "making sense" out of what they experienced; and (c) by being dynamic and enthusiastic as opposed to easy going as an approach to life. All parents believed that their children should have wide latitude on the expression of questions and ideas, but farm more than non-farm families expected that differences and conflict generated by this "open expression" of ideas needed to be resolved.

READING ACCURACY

One measure of a child's likelihood to successfully engage in formal educational processes is reading accuracy. Most simply, reading accuracy is a child's capacity to correctly read developmentally appropriate words in story format without error. Five errors per 100 words would be a reading accuracy score of 95; 50 errors per 100 words would be a score of 50—and so on. Of interest in this study were the attributes of parenting that are associated with reading accuracy scores. For the 28 children sampled, reading accuracy scores ranged from 11 to 98 with an average (mean) score of 67.65. Reading accuracy scores for farm children were slightly lower (57.4) than for non-farm children (69.9). This difference was not statistically significant. A systematic comparison of parenting styles and attributes for children with high vs. low reading accuracy scores did not result in the identification of any significant or meaningful associations.

Discussion and Implications

Analysis and interpretation of the quantitative and qualitative data generously provided by the rural limited-resource families and community service providers participating in this study depicts a context for children that is characterized by economic uncertainty and parental stress. Limited-resource families, in particular, face seemingly (to them) overwhelming demands generated by the dynamic and uncertain nature of their employment, their children's schooling, and the changing community agencies, organizations, and services upon which they depend. The experience of everyday life for many limited-resource families is so diversified—given multiple jobs, disconnected community services, uncertain child care, and limited personal coping skills—that their lives can best be described as a "patchwork." Transportation and housing plays a particularly critical role for families trying to improve their quality of life. The better paying jobs are often only available at some distance outside of the immediate community and county. Those children with families fortunate to have access to reliable transportation and extended child care have a chance at well being, while those children with less fortunate family circumstances seem to be at considerable disadvantage. Families caught in chronic stress and ambiguity and seemingly unable to gain a sense of mastery as they encounter their community create an immediate context for their child that impedes their development of a positive sense of self esteem.

Rural communities face a unique set of constraints when trying to assist and support limited-resource families. While service providers in urban communities may have high case load ratios, those providers in rural areas have case loads spread out over extended distances. Many informal groups that have historically provided for limited-resource families are simply running out of supplies (i.e., food pantries, surplus clothing) due to increasing demand. Availability of specialized services for children is often limited in rural communities because of the sheer lack of numbers to justify commitment of resources. As communities attempt to establish centralized and wrap-around services, they encounter increased costs in reaching and maintaining contact with those families most in need.

The aspect of the study examining parenting styles and reading accuracy has both specific and general implications. Specifically, the findings confirmed both the relative effectiveness and ineffectiveness of any particular parenting style as associated with children's reading accuracy. It appears that there is not one "best" way to parent children given the desired goal of enhancing reading accuracy in an effort to maximize a child's readiness for school. While it is always important that parents do everything within their capacity to "prepare" their children for the challenges of formal education, it is equally critical that schools are prepared to accept and engage children in a manner which stylistically "fits" with the child's family. This finding is also true for the delivery and provision of community services to limited-resource families. Given the vast diversity of family styles and circumstances, any community is particularly challenged to "fit" families in need.

This study—albeit limited—presents an understanding of the context of rural poverty. The economic, personal, and family stresses experienced by children living in families of poverty were described. A variety of coping strategies—ranging from amazing to mundane—were described by families as they dealt with their changing circumstances. Many of these families were experiencing the negative impact of rural restructuring. The challenge is to better understand the many faces and contexts of poverty and to continually consider the balance of intended and unintended consequences of economic and social reform as impacting those most in need—our children.

References

Adams, T. K., & Duncan, G. J. (1992). Long-term poverty in rural areas. In C. M. Duncan (Ed.), Rural poverty in America (pp. 63-93). New York: Auburn House.

Bane, M. J., & Ellwood, D. T. (1986). Slipping into and out of poverty: The dynamics of spells. Journal of Human Resources, 21(1), 1-23.

Boyer, E. (1993). Ready to learn: A mandate for the nation. Young Children. March, 54-57.

Constantine, L. L. (1986). Family paradigms. New York: Guilford.

Deavers, K., & Hoppe, R. (1992). Overview of the rural poor in the 1980's. In C. M. Duncan (Ed.), Rural poverty in America (pp. 3-20). New York: Auburn House.

Duncan, G. (1984). Years of poverty, years of plenty: The changing economic fortunes of American workers and families. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Garrett, P., Anandu, N., & Ferron,J. (1994). Is rural residency a risk factor for childhood poverty? Rural Sociology, 59 (1), 66-83.

Huston, A. C. (1991). Children in poverty: Developmental and policy issues. In A. C. Huston (Ed.), Children in poverty: Child development and public policy (pp. 1-22). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Imig, D. R., & Phillips, R. G. (1992). Operationalizing paradigmatic family theory: The Family Regime Assessment Scale (FRAS). Family Science Review, 5(3), 1-18.

Jensen, L. & Eggebeen, D. (1992). Child poverty and the changing rural family. Rural Sociology, 57(2), 151-172.

Kantor, D., & Lehr, W. (1975). Inside The Family. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lichter, D., Cornwell, G., & Eggebeen, D. (1993). Harvesting human capital: Family structure and education among rural youth. Rural Sociology, 58(1), 55-75.

Lichter, D. T. & Eggebeen, D. J. (1993). Rich kids, poor kids: Changing income inequality among American children. Social Forces, 71(3), 761-780.

Lorenz, F. O., Conger, R., Montague, R., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (1993). Economic conditions, spouse support, and psychological distress of rural husbands and wives. Rural Sociology, 58(2), 247-268.

Sherman, A. (1992). Falling by the wayside: Children in rural America. Children's Defense Fund: Washington, D.C.

Voydanoff, P. (1990). Economic distress and family relations: A review of the eighties. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 1099-1115.

Wenk, D. A., & Hardesty, C. (1993). The effects of rural-to-urban migration on the poverty status of youth in the 1980s. Rural Sociology, 58(1), 76-92.