The University of Michigan in China

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

4. The Barbour Scholars

In 1917, some 20 years after the graduation of Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu, the University of Michigan (U-M) made its first formal overtures of welcome to women from Asian countries with the Barbour Scholarship. Founded and funded by Levi Lewis Barbour, a graduate of U-M and a regent for the University, the scholarship invited qualified women to study at Michigan and then return to their home countries enriched with their newly acquired knowledge. As Barbour himself put it in a letter to U-M President Harry Burns Hutchins in 1919, the idea of the scholarship “was to bring girls from the Orient, giving them an Occidental education, and let them take back whatever they found good, and assimilate the blessings among the people from which they might come.”

To date, more than 700 women from India to Turkey to China have come to the University of Michigan supported by either the Barbour Scholarship or (for advanced degrees) the Barbour Fellowship. In the early years of the program, women from China made up the majority of the scholarship recipients. For many of these women, the Barbour Scholarship proved to be a springboard into positions of power and authority at home in China, making space for women in traditionally male-dominated institutions. While there are too many such examples to cover in a single chapter or book, this chapter will tell the story of Levi Barbour and two of the most impressive leaders—Ding Maoying (Ting Me-Iung) and Wu Yifang—who owed their success in medical and educational institutions in part to Barbour’s philanthropy.

Levi Barbour attended the University of Michigan during its fledgling years. Born in 1840 in Monroe, Michigan, Barbour received a BA in 1863 and a law degree two years later. From the earliest years of his career, Barbour seems to have been oriented toward charity and social justice. After passing the bar exam and marrying Ann Arbor local Harriet Hooper, Barbour settled in Detroit as a junior partner at a law firm in 1866. Barbour worked hard to develop the city, playing “a leading role in the purchase of Belle Isle for the park system.” He also “organized a secular agency, the Association of Charities, a forerunner of the United Way, and served as its first president” (Faerber 20).

But of all the social issues that concerned Barbour, the accessibility of college education was perhaps the most important to him. In 1897, a decade after Angell returned from China and the year after Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu’s graduation from the University of Michigan, Barbour published an essay called “College Training for Professional Men.” Tellingly, the essay opens with this line: “I can fancy but one broader or more important topic of discussion before an audience of college men than this, and that would be ‘College Training for Everybody’” (Barbour 1). Later, Barbour wrote that he hoped college education would someday be as universal and accessible as primary school—a core value that inspired much of his philanthropic work.

The struggle to allow women to attend the University of Michigan must have been fresh in Barbour’s mind. As a student himself in the mid-1860s, female students would have been allowed to receive a co-ed high school education but not participate in university classes. In 1858, a committee of regents produced a divided report on the appropriateness of higher education for women, and while then president Henry Philip Tappan “strongly approved of higher education for young women . . . he advocated for separate facilities and curricula,” believing that “women were physically and intellectually incapable of competing with men in the college environment” (Faerber 5). It wasn’t until 1870 that, prodded by the state legislature, U-M changed its policies and admitted its first female student.

Portrait of Levi L. Barbour. Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

When Barbour began his first term as regent at the end of the 19th century, it’s no surprise that he and President Angell became close friends as well as colleagues. Both men shared a belief in women’s suffrage and in the importance of making a university education accessible to women. Barbour “worked closely with President Angell in enthusiastically implementing the Board’s policy admitting women to the University with equal privileges,” and together they established the University’s first dean of women position, filled by Dr. Eliza Mosher. During these years, Barbour made a gift of land in Detroit to the University, the sale of which was used to build the Barbour Gymnasium, a center for women’s activities on campus.

Although it took several years after his 1913 tour of Asia to get the scholarship officially off the ground, Barbour wasted no time in implementing the principles of the fund. In 1914, he invited two Japanese women to study in the United States. Barbour payed their expenses, hired tutors, and even housed them in his own home for their first few months. By 1917, after several years’ worth of preparation with President Hutchins, a formal proposal to the board of regents, and a donation of some $55,000, the Barbour Scholarship was officially implemented. That year, one Gladys Ding Chen from China became the first official Barbour Scholar.

From 1917 until his death eight years later, Barbour shepherded the program. He doubled the endowment, helped manage and revise the program’s policies, and gifted several rental properties to the University so that the program might be self-sustaining (Faerber 23). When he learned that one student had contracted tuberculosis due to inadequate living conditions, Barbour built a new residence hall for women on campus. Named after his mother, a lifelong role model for Levi, the Betsy Barbour House still stands on Ann Arbor’s central campus today. When Barbour passed away in 1925, he left the furniture from his own household to the Betsy Barbour Residence Hall and the entirety of his homestead to the scholarship program.

Levi Barbour devoted himself to the cause of making education accessible to everyone, particularly women. As I’ll explore in the rest of the chapter, Barbour’s investment in the ability and promise of Chinese women has paid immense dividends.

Ding Maoying: Hospital Director, Aid Worker, and National Representative

One such Michigan graduate was Ding Maoying. Ding attended the University of Michigan twice, receiving a medical degree in 1920 and returning eight years later for a Barbour Fellowship. Over the course of her career, Ding became a director of the Tianjin Women’s Hospital, the head of the Chinese delegation to the Pan-Pacific Women’s Conference in Honolulu, and the author of one of the earliest books on prenatal care for mothers in China.

Gathering of Chinese students at a Barbour program ball. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Professor Frank L. Huntley (left), secretary of the Barbour program beginning in 1946, with his wife (center) and Chiang Kai-shek, generalissimo of the Nationalist forces in China. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

The story of Ding’s extraordinary career begins at the McTyeire Missionary School in Shanghai. There she met Tsao Li Tsuin, a student several years older, who became a mentor and friend and encouraged Ding’s interest in medicine. Soon this friendship—and Ding’s future—was tested. Rather than allow his daughter to complete her education, Ding’s father had betrothed her to “a sickly, older friend of his” (Ting). Sources differ on how she escaped. Some say she ran to the missionaries for help, while her great-niece Evelyn Kay Ting thinks it more likely that her friend Tsao Li Tsuin helped her escape. Either way, Ding fled marriage and made her way to America.

Portrait of Ding Maoying. Alumni Association Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

In the United States, Ding finished her undergraduate degree at Mount Holyoke College before enrolling in the University of Michigan Medical School. During her time in Ann Arbor, Ding began to exchange letters with Dr. Abby Turner, an instructor from Mount Holyoke who would go on to become a lifelong correspondent and confidant. These letters survive today, and they provide windows into Ding’s experiences as a student in America and as a doctor in China. Ding described, for example, taking a summer course in experimental physiology with one Dr. Cope, who devoted “his whole time to students.” Ding wrote that she thought that it was “just as good a course as you can get in this country.” She also enjoyed Ann Arbor in the summertime: “There are many beautiful shady trees. There are good many places for long walks and recreation. Barbour gymnasium is opened to all summer school students. There is a small swim pool and many showers” (letter ca. 1919–1920).

But as much as Ding immersed herself in her studies at Michigan, her home country was never far from her mind. As she wrote in 1919, a year before her graduation,

I will do what is the best for my people in China. There are few who are fortunate as I to be able to study abroad. There are many physicians in China who have no business to be. After my years training I ought be able to do some thing for my people. Dr. Tsao wants me to help her. After all the only thing I want to do is to give my whole self to my country. (Letter 1919)

Envelope of a letter Ding sent to Dr. Abby Turner. Courtesy of Donna Albino, http:// www.mtholyoke .edu/ ~dalbino.

Dr. Tsao, Ding’s old friend from the McTyeire Missionary School, was now herself a practicing physician. When Ding graduated with an MD in 1920, she spent two years interning in hospitals and gaining practical experience; in 1922, after nearly a decade abroad, Ding returned home to China. The poverty and war of the early 1920s, a result of the period of warlordism that followed the fall of the Qing dynasty, must have been a surprise. “There is fighting in [the] northern part of Chi-li,” Ding wrote. “We people have nothing to do with it. These war-lords will eventually kill themselves. That will be the salvation of China. I am happy that I took a training home to help my people” (June 1922). And Ding was able to reunite with her father, despite her disruption of the betrothal that he had arranged. “My father was so proud of me,” she wrote in the same letter. “It certainly was a happy homecoming.”

Unfortunately, this happiness was not to last even as long as the summer. On August 11, 1922, Ding prepared to take her friend Dr. Tsao out for dinner. But as Li Tsuin Tsao started to dress, she complained of a headache. “She suffered only five minutes and went sound asleep until her last breath,” Ding wrote. Dr. Tsao died of a cerebral hemorrhage just three days later. With Dr. Tsao’s sister having also passed away just weeks before, Ding was left alone in Tianjin: “Within three weeks, two of my best friends left me . . . Everything is like a dream to me now” (September 1922).

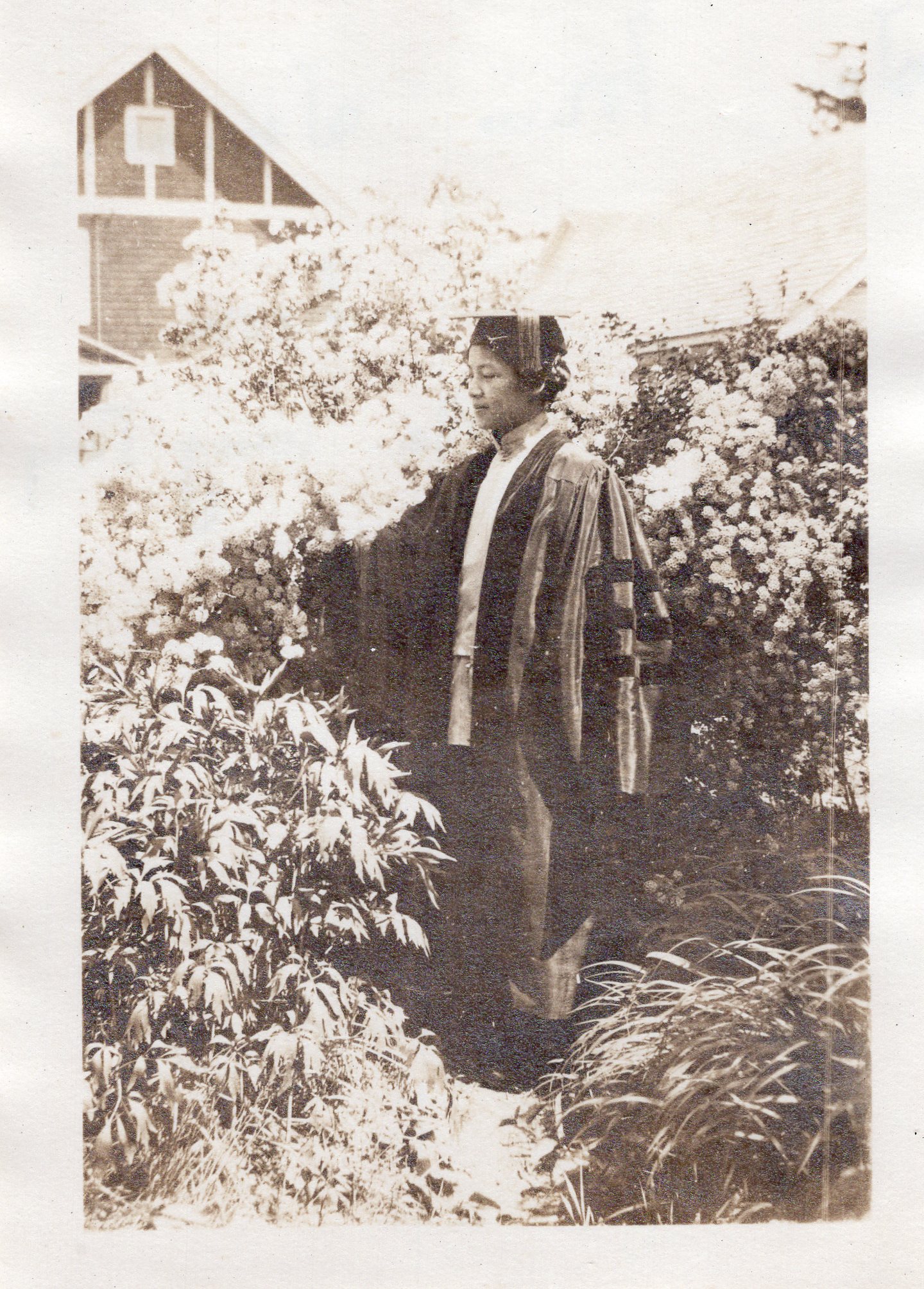

Ding Maoying in Ann Arbor, ready to graduate in 1920. Courtesy of Donna Albino, http:// www .mtholyoke .edu/ ~dalbino.

The heavy workload at the Peiyang Women’s Hospital in Tianjin, however, gave Ding no time to grieve. With Dr. Tsao gone, much of the workload and authority fell on Ding. “Work is too heavy for a young doctor,” Ding wrote. “I would like to have enough more time to read up my cases. I did my own laboratory work also. Since the death of Dr. Tsao I had to have charge of hospital account” (September 1922). The crossed-out enough is particularly poignant—Ding, so overwhelmed by work, wished only for more time, not enough time. In the same letter, she gives some sense of the particulars of her burden: “Within three months I have seen three thousand patients at clinic, delivered forty five babies, operated ten times, made sixty calls outside.” No wonder that Ding longed for the comparatively easygoing life at Michigan just two years before: “I miss my college life. I would give anything if I could just get away for a good walk in the woods” (September 1922).

Ding in her back yard in Tianjin, 1922. Courtesy of Donna Albino, http:// www .mtholyoke .edu/~dalbino.

Nonetheless, Ding felt it was her duty to carry on Dr. Tsao’s “unfinished task,” as she called it. Ding was forced to deal with the challenges of being in a position of authority while still so young: “It is the hospital management that tries my temper. Being young in experience I often would not know how to deal with people” (December 1922). For the next eight years, Ding persevered and built up the hospital, hiring additional doctors and nurses, sending others to America for training, and expanding the hospital’s technical capacities. Armed conflict among Nationalists, Communists, and local warlords was a perpetual concern. In the winter of 1924, Ding wrote that civilians “would not dare to be on [the] streets at night in October and November” and that “militarists and their soldiers have made us their slaves” (December 1924). Ding’s father turned 60 this same year, and her busy schedule and the long travel time (30 hours by train) were not the only reasons she chose not to visit: “Trains are loaded with soldiers, and anything might happen to a woman.”

The end of the 1920s brought some relief from her duties. First came an invitation to be a delegate at the first Pan-Pacific Women’s Conference in Honolulu. “One of the leading international women’s social movements of the twentieth century,” organizers from the United States, Australia, and New Zealand brought together women from across the globe to promote “inter-cultural exchange” and “inter-racial friendship” (Paisley 2). Ding at first refused the invitation—Dr. Mary Stone (Shi Meiyu) had also been invited, and Ding “want[ed] Dr. Stone to represent Chinese women doctors” (April 1928). In the end, however, it was Ding who attended the conference and advanced the reputation and independence of China. When Eleanor Hinder, an Australian woman who had worked in Shanghai with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), suggested that the following year’s conference be held in Shanghai, Ding rebuffed her. “If the next conference is going to be held in China,” Ding said, “the invitation should be from Chinese women.” This was “reportedly an electrifying declaration that the time had come when Chinese women would speak for themselves” (Lake 51).

Ding returned to China after the conference only briefly—in 1929, four years after Levi Barbour’s death, she was awarded a Barbour Fellowship, a postgraduate research grant at the University of Michigan. Returning to Ann Arbor provided some much-needed time for rest and recovery. During her year-long fellowship, she had the freedom to study as much as she pleased and to attend “good lectures and fine concerts.” “I am really having a most joyful time,” she wrote once the fall semester had gotten under way (November 1929). Much of her work during the Barbour Fellowship focused on writing a book for mothers in China who needed access to modern obstetric advice. The book was “well received by parents here. Many have expressed that this is just the book they need for care of their children. . . . Every mother gets a copy before she leaves this hospital” (January 1935). In the book’s acknowledgments is a dedication to Levi Barbour and his “foresight and generosity.”

Soon after the second printing of Ding’s book, the mayor of Tianjin chose Ding to be the director of the Tianjin Infant Asylum, which housed approximately 100 unwanted girls. “This is the first time in the history of Tientsin [Tianjin] to have a woman in a government position,” Ding wrote. “The mayor of the city wanted a woman to take this work as he said it is a woman’s job” (July 1935). The men, clearly, had not been doing an adequate job:

You have no idea what a poor sanitary condition the home was in. . . . The home had a man doctor who did nothing but took his monthly salary as his side dish. Politics is politics everywhere in the world . . . I cannot begin to tell you what sweeping I have done these past two months. I cleared the place of useless men and women who were good for nothing. I actually fired thirty nine people within these two months. (July 1935)

Ding had come a long way from the nervous graduate forced to take command at the Peiyang Hospital. Here she was comfortably in command. In just the first few months of her leadership, Ding tore down an old, inadequate building and ordered a new one built; organized a class for nursemaids; battled the spread of contagious illness among the residents; and devised new diets for the children. She began to teach the older girls to take care of the younger ones: “I am trying to make this institution like a home,” she wrote, and one is inclined to believe Ding when she said, “Everybody in the city of Tientsin is happy over the fact that I have been chosen to reorganize this institution” (July 1935).

Ding (center) with her Barbour cohort, 1930. Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Despite Ding’s pleasure at the progress she was making at the hospital and at the asylum, the threat of armed conflict hovered over all her work and is omnipresent in her letters to Miss Turner. Tianjin in northeastern China had long been a key port, valued by the foreign powers that controlled large concessions in the city for its direct line of sight to the capital, Beijing, little more than 100 kilometers inland. A site of much conflict, the Boxers had seized partial control of Tianjin during the rebellion at the end of the 19th century. Now, as Ding tried to shore up the city’s educational and medical infrastructure, the threat from an aggressive Japan loomed over her. Writing at the end of 1935, Ding predicted, “Soon or late Japan will press China into war,” before describing being called in for questioning by a Japanese spy (October 1935).

Ding’s prediction came true. The Second Sino-Japanese War began in early July 1937, and by the end of the month, Tianjin was under fire. Warplanes bombed some of the city’s most important sites, burning Nankai University to the ground and blowing up the police station, which was “very near the hospital” (August 1937). Ding did her best to move her patients, many of whom were “on the point of a nervous breakdown,” by ambulance to other locations. Ding herself, however, stayed put, feeling “duty bound” to stay with her hospital (August 1937). Later that year, Ding was able to pass a letter to Miss Turner through an American friend, which meant it was uncensored by the Japanese government. The letter describes further aerial strikes against the city, her hospital being rocked by bombs, and moving patients to the basement: “We are not afraid to die . . . but how long will our nerves last we do not know” (September 1937). Ding addressed Miss Turner in the letter, and through her the rest of the world: “We do not ask the world for anything but a chance to live peacefully by ourselves and harmoniously with others.”

After June 1938, there is an eight-month gap between letters. In March 1939, she wrote a letter to Miss Turner that referred to a mutual friend who had informed her of “events here.” She followed this up with an ominous line: “I am thankful that as a child I was brought up strictly and simply and accustomed to many small privations” (March 1939). More of the story emerges in later letters—Ding and a nephew were detained for 19 days in prison by the occupying Japanese army. No reason was given for the arrest, though Ding was questioned about her political affiliations: “I won my battle. They could find nothing and they had to give me freedom . . . I am not interested in political affairs at all” (April 1939). A note from Ding’s great-niece Evelyn Kay in the Mount Holyoke archive relates an anecdote from Ding’s nephew: apparently Ding “persisted on flying the American Flag on her car during the occupation and landed both of them in Japanese Prison.”

The Japanese occupation of China continued through the end of World War II. During this time, Ding ministered to thousands of refugees, relocated to Shanghai, gave birth to a baby girl, and survived being buried in rubble by an airstrike. After a year of silence in her correspondence with Miss Turner, Ding described the experience:

Soon the buzzing of the heavy bombers and the crackling of the anti-aircrafts were covered up by a series of the whizzing of the descending bombs and the shaking explosions, following one of which I felt myself torn from Ray and thrown into the middle of the room face downward, and the house had come crashing down on me. Instinctively I had thrown up my left arm so that my head came to rest upon it thus leaving a breathing space. The dust was so thick that it was hard to breathe . . . I was not in the least frightened and had wished I were a strong man to have the strength to lift up the load on my back so that I could breathe better. The truth was I could not even move a hair. Within half an hour under the guidance of my voice they dug me out without a scratch to speak of, only a large bruise over my left hip bone where I was hit by a beam. . . . Indeed, it was a real good fortune of a misfortune! For there were only six layers of floors and ceilings on top of me; the roof of this room had not caved in nor had the walls fallen. There could have been so many “if’s,” only one of which could change my year of silence into many years. (June 1941)

Ding spent her postwar years in China working as the chairman of the International Relief Committee. But restoring health and order to Tianjin was not easy; in the wake of the Japanese occupation, the civil war between the Communists and Nationalists reignited. Ding’s letters at the end of the 1940s bemoan the loss of rights—freedom of speech, freedom of religion—as the Communists came to power. In her great-niece’s recollection, in 1950, Ding left everything behind “when it became apparent that her American education was a danger to her friends” (Ting). She crossed the border into Hong Kong and from there flew to the United Kingdom. Ding sent several letters to Miss Turner from England, writing about the welcome peace and quiet, about her hope that the US Embassy would let her into America, and about her fears for her own country.

In the end, Ding did make it back to America, where she spent two more decades serving as a physician and an instructor. Ding’s is a remarkable story. For her, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Fellowship were springboards into a position of authority in China, where she ran hospitals, rebuilt the Tianjin Infant Asylum, chaired the International Relief Committee, and represented her country at international conferences. During some of China’s most tumultuous and difficult years, Ding Maoying became a pillar of leadership and support for the cities in which she lived.

Wu Yifang: China’s First Female College President

Like Ding Maoying, Wu Yifang studied at the University of Michigan as one of the early Barbour Scholars. She, like Ding, found herself vaulted into a leadership position as a young woman: at 35 years old, having just graduated with an advanced degree in entomology, Wu was selected to be the president of Jinling (Ginling) College in Nanjing, making her the first ever woman in China’s history to hold the office. Wu became president at the end of the 1920s, which meant that she was soon to be responsible for keeping the college intact and its students safe during China’s civil war and the Japanese invasion. Like Ding Maoying, who was working in the same period in northern China, Wu in the south rose to the occasion in spectacular fashion.

Wu Yifang (center) with two classmates at the University of Michigan. A. Grace Edmonds scrapbooks, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Wu Yifang was born in 1893 on the cusp of massive social change in China. As the third of four children in a relatively upper-class family, Wu’s feet were bound as a young girl, although they were later unbound. And while her family had once been known for its scholars—her great-grandfather and grandfather had both passed the national civil service examination at the highest ranks—her father had “passed only the lowest level.” With her family’s fortune dwindling, “Wu’s father reluctantly purchased a low-level official job with the help of family connections” (Waelchli 52). Despite the family’s financial hardship, Wu Yifang and her older sister, Yifen, managed to get an education. Yifen, in particular, is noted to have been “very much interested” in education. When their parents refused to send them to the new girls’ school in Hangzhou, “Yifen, desperate to attend school, attempted suicide.” This was enough to persuade their parents, and in the spring of 1904, the two girls, 15 and 11 years old, “took an eleven-day journey by sedan chair, houseboat and steamer to Hangzhou” to attend school (53).

The children had five years to enjoy their education before tragedy struck. In 1909, they received a message calling them home. Their father, it turned out, “had been persuaded to use government finances in two business schemes. When these failed and he was asked to account for the funds, he committed suicide.” This began a string of tragedies that shattered the family. Wu Yifang and her sister left school and moved with the rest of the family to Shanghai, where they lived with an uncle. Two years later, Wu’s older brother committed suicide as his father had, “drowning himself in the river.” Her mother, already ill, died soon after. And on the night of her mother’s funeral, Wu’s older sister, faced with the overwhelming task of caring for her siblings alone, committed suicide herself. Wu, now just 18 years old, had “lost her three closest relatives within a month” (Waelchli 55).

In the years that followed, Wu Yifang leaned on her uncle, Chen Shutong, who encouraged her to continue her education. In fact, “according to one of Wu’s former students who knew her well,” Wu Yifang also “contemplated suicide after the deaths of her family members,” and it was partly due to her uncle’s support and encouragement that she survived her grief (Waelchli 56). In the winter of 1916, Wu enrolled in the recently opened Jinling College, and it was there that she truly began to recover from her family’s dissolution. As Wu remarked in a tribute to a friend, Zee Yuh-tsung,

When I entered Jinling, I had suffered deep sorrow from a family tragedy. . . . In Jinling it was Yuh-tsung’s Christian Life and her loving sympathy for me that uplifted me out of self-imposed isolation. Gradually I understood the real meaning of life and learned to aim at a worthy life purpose. (57)

As a college student, Wu Yifang displayed a natural bent toward leadership. She organized a student government association in which she served as chairwoman and then president of her senior class; she also “push[ed] for more student autonomy,” intent on showing “that students were capable of enforcing dormitory rules and other regulations themselves” (Waelchli 58). But perhaps even more important, the students at Jinling College imagined for themselves a position of agency in China more generally. In a class skit, Wu Yifang played an upper-class lady who decided to give gifts to the poor instead of her wealthy friends; in another skit, the four class presidents “gave a presentation depicting Jinling women as a light going out to China.” The college students were not shy about putting these ideals into practice, opening a “half-day school for illiterate girls” and starting a “Sunday school for neighborhood children” (60).

Upon graduating from Jinling with a bachelor’s degree, Wu Yifang applied for and received a Barbour Scholarship at the University of Michigan. For the next six years, she worked through master’s and PhD programs in entomology, teaching classes to undergraduates and continuing her own research as a graduate student. But in 1927, before Wu had even finished her doctorate program, she received word that the Jinling College Committee (GCC), a governing board made up of representatives from American missionaries and colleges, had elected her to be Jinling’s next president. She would be the first Chinese woman to ever hold such a post—the position was hers, if she wanted it.

While Wu had made a name for herself as both a diligent scholar and a willing leader, electing someone not yet out of a doctorate program with no administrative experience was still an unorthodox decision. And in fact, the GCC would not have made such a decision if not for pressure from the Nationalist government to place Chinese citizens at high levels of Western-run institutions. Antiforeign and anti-imperialist sentiment came to a head during the “Nanjing Incident,” in which several Western men, including the vice president of the University of Nanjing, were killed by roving bands of southern soldiers. When one such mob came to Jinling’s campus with “slogans like ‘Kill the Foreigners,’” Jinling’s foreign faculty hid in an attic while the Chinese faculty led the soldiers on a “wild goose chase around the buildings” (Waelchli 100). While Jinling’s foreign faculty managed to flee Nanjing safely, this proved to be a turning point in the college’s administration, even when the faculty eventually returned to the city. After the violence died down, it became clear that Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang government meant to enforce the regulation about Chinese leadership in local institutions, and the GCC got down to the business of electing a Chinese president.

Wu Yifang (top row, fourth from left) with her Barbour cohort, 1925. Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Wu Yifang with Mrs. George Nichols. Anne Louise Welch Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

For Wu herself, though, the decision to accept the position was a difficult one. While Wu had planned to return to Jinling as a professor of biology, accepting the leadership of the whole institution was a much more fearsome proposition. Writing to a member of the GCC, Wu said,

I learned of the possibility of being called to fill an important position during this transition period, and I had to face the fact that I am not the least bit prepared for such a task. I never expected to go into administrative work and always wanted to teach along my own line of Biology. I thought over the situation carefully and told Mrs. New frankly that even if circumstances should turn out to be such that I ought—duty toward Jinling—to accept the position, it will be just temporary, only for this sudden and short period of transition. If conditions should become such that no great change is necessary, or if the Board of Control should succeed in finding some other person for the position, I would be only too glad to serve G.C. as a teaching faculty. (Waelchli 111–112)

Despite Wu Yifang’s misgivings, she returned to China in the summer of 1928 and seemed to fall naturally into the role of Jinling College’s president. That autumn, she gave an inauguration speech that was “beautiful and moving” and filled the students with pride in their “young, pretty president.” Her first months reassured the GCC that they had made a good decision: “More and more I am coming to have respect for and confidence in her judgment and ability . . . I think she has already won the confidence of her faculty.” The former president of Jinling, Matilda Thurston, who had been unceremoniously ousted from her position, wrote that because of Wu Yifang’s capability, “my heart is at rest about Jinling” (Waelchli 119).

Wu earned the confidence and satisfaction of Jinling’s old guard by resolving a crisis that arose “less than a month” into her tenure: “A general wanted to commandeer the campus as temporary headquarters for Shanxi warlord Yan Xishan” (Waelchli 120–121). Luckily, Wu was able to use political contacts to resolve the situation, asking an old school friend’s husband to make an appeal to the foreign minister (121).

For the next decade, Wu Yifang became an increasingly public figure, both internationally and at home in China. Almost as soon as she was elected, Wu began to be asked to speak at conferences. In 1929, she traveled to Japan as a delegate at the Institute of Pacific Relations; four years later, she represented China at the International Women’s Congress in Chicago, and while in America, she “visited thirty-three cities and spoke over two hundred times” (Waelchli 139). Wu joined and led several Christian associations in China, including the National Christian Council, which elected her as chairwoman in 1935. In just a few short years, Wu had gone from studying biology as a graduate student at the University of Michigan to being one of the most famous women in China: “By the early 1940s, she was so well known by certain groups in America that she was sometimes referred to as the second most important woman in China, behind Soong Mei-ling,” wife of Chiang Kai-shek, head of the Nationalist government (138).

In fact, despite Jinling’s troubles with Nationalist troops and some early “misgivings” on Wu’s part about Chiang Kai-shek’s leadership, by the 1930s, Wu Yifang “supported Chiang and became good friends with his wife, Soong Mei-ling.” Wu began to receive social invitations from the Chiangs, and at several national conferences and dinners, they were seated together. In the winter of 1934, Jinling College invited Chiang and his wife to a “baccalaureate service,” where the generalissimo “gave a short talk.” In 1936, Zhang Xueliang, “the Young Marshall”—a military ally and confidant of Chiang Kai-shek—betrayed Chiang, kidnapping him to be used as a bargaining chip with the increasingly powerful Communist Party. Wu, hearing the news, “went immediately to see Soong Mei-ling.” Jinling canceled its holiday plans, and Wu is said to have taken Chiang’s kidnapping “so personally that it was almost impossible to carry on her work”; when “Chiang was released, Wu personally informed the faculty and students” (Waelchli 143).

Wu Yifang’s position as the president of Jinling College—one of the only accredited colleges for women in China and the only woman to hold such an office—placed her squarely on the national and international stage. And although she came to the position with little formal leadership experience, Wu seems to have inhabited her new role with grace and ease, charming even the highest levels of China’s leadership. However, the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) was perhaps the greatest test of Wu Yifang’s capacity for leadership. As the Japanese army pushed through China’s northeastern coast and prepared to invade southern China, Wu dedicated herself to guiding her college and her country through the conflict. Wu ran the Chinese Women’s Association for War Relief alongside Soong Mei-ling, contributed to a Christian organization for war relief, comforted and guided her students through the first air raids over Nanjing, and advised her foreign faculty on whether to leave the city. All in all, she was, as a colleague described her, a “great and fearless general” and “solid rock through and through” (Waelchli 172–173).

As the war escalated, however, the government ordered universities in the Nanjing area to close. Jinling shut down all classes and dismissed the faculty and staff except for a skeleton crew of an “emergency committee” and opened several smaller provisional branches farther inland. Some of Jinling’s Western faculty, against the advice of the consulate, remained in Nanjing and “deflected requests for use of the buildings to keep them in reserve for civilian relief efforts” (Waelchli 171). By the end of the first year of the war, the invasion of Nanjing was all but imminent, and Wu’s colleagues and the GCC begged her to leave the city. That December, Wu gave in, boarding a British vessel due to leave Nanjing: “Wu had gotten out of Nanjing just in time; shipping on that part of the Yangtse river came to a halt shortly thereafter” (175).

Leaving her college and her colleagues alone in a city under fire felt to Wu like running away, even though she continued to manage Jinling from a provisional outpost in Wuchang. As Wu sailed away from her all-but-fallen city, she was struck by a deep sense of guilt—as she called it, “the most agonizing experience I had. . . . On the boat I did not have any peace, thinking of the small committee I left behind to take charge, and thinking of all the large number of people who could not get away” (Waelchli 174). No sooner had Wu set sail than she reconsidered her decision to close the school. Perhaps, as she wrote in transit, it was up to her to “follow the hard course . . . I for one am ready to go if and when the college is to start work” (175).

It is a good thing that Wu was unable to turn back: she set sail on one of the last barges out of the city on December 1. Eleven days later, on December 12, “General Tang Shengzhi, charged with defending the city, abruptly left Nanjing” (Waelchli 176). In the days that followed, Japanese soldiers poured into the city, “engaging in an orgy of violence including rape, looting, arson, and killing” now known as the Rape of Nanking. As this trauma unfolded, Jinling College became a refuge for hundreds, then thousands of women and children fleeing the terror in the rest of the city. The emergency committee hung American flags on the walls of the campus in an effort to deter Japanese soldiers, and when that didn’t work, one woman, Minnie Vautrin, ran across the campus challenging marauding soldiers, doing her best to be a shield for the refugees within.

In the later days of the war, Wu Yifang led Jinling College from its new home in the city of Chengdu. There was an unending list of practical problems to solve: attracting qualified students, finding new faculty, funding the school, and supplying students with food as prices surged. And yet Wu still found time to continue her larger political efforts. In addition to her war relief work, Wu was elected to the Kuomintang’s parliamentary body, the People’s Political Council (PPC), where she eventually was chosen to belong to the five-person presidium that also included Generalissimo Chiang (Waelchli 233). Not only was she 1 of only 10 women in the whole 200-person PPC; she was the only woman on the elite presidium. Just as she had quickly won over the faculty of Jinling as a new president, Wu Yifang was soon recognized as one of the most valuable members of the presidium: “Local newspapers deemed her the best presiding officer . . . Capable [and] hard working, . . . [she] dealt with motions in a closely reasoned and well-argued fashion” (233–234).

As a cap on an already remarkable career, in 1945, Wu was chosen to be one of the nine Chinese delegates (again the only woman) sent to the San Francisco Conference to establish the United Nations charter. Despite health troubles and mounting work at Jinling, Wu accepted the offer. She saw China’s position among the UN’s permanent members, the “Big Five” nations, as another step along the road toward a unified country and a representative government. In the face of continued conflict between the Chinese Communist Party and the Nationalist government, Wu saw that China had more work yet to do:

China as one of the “Five” must build up herself [and] develop a strong democracy and industrialize in order to support our moral stand on respecting international law and justice. I see a great future for our country, but it depends upon how our government and people will respond. (Waelchli 251)

Wu Yifang spent the rest of her life helping China do this work. She ran Jinling College through the end of China’s civil war; through the reconstruction of the campus in Nanjing; through the country’s transition to Communism and concerns about political reprisals; through the growing anti-American sentiment that threatened Jinling’s foreign faculty and, by 1951, forced them to resign en masse; and through Jinling’s eventual merger with the University of Nanjing.

Beloved by her students and colleagues and by local and national politicians, and with few critics recorded anywhere, Wu Yifang seems to have been an ideal leader. She worked only for the well-being of her students and fellow citizens; for example, she voluntarily turned over extra income from speaking engagements to Jinling College. Wu had the gift of seeing the best in any situation, of working flexibly in many political contexts. And yet, somehow, Wu Yifang never lost her critical edge: over the years, she spoke and wrote critically of any policy—American, Nationalist, or Communist—that seemed likely to be harmful to her beloved college and country.

Barbour’s Legacy

It is a testament to Levi Barbour’s generosity and foresight—and to the large number of ambitious, brilliant Chinese women who sought an education during an era when doing so was far outside the norm—that there are far more worthy Barbour Scholars to discuss than can possibly fit in one chapter or one book. Wu and Ding are just two of hundreds of noteworthy Barbour Scholars, including Lucy Wang, who became president of Hwa Nan College soon after Wu was elected at Jinling, or the famous playwright Li Man-Kuei. The accomplishments of the Barbour Scholars are so great that they deserve a book unto themselves.

Works Cited

- Barbour, Levi L. College Training for Professional Men. Lansing, MI: R. Smith, 1897. Print.

- Barry, Sara, and Jennifer Grow. “To Boldly Go.” Alumnae Quarterly, Spring 2015. Web. <http://alumnae.mtholyoke.edu/blog/to-boldly-go/>.

- Bordin, Ruth B. “Levi Lewis Barbour: Benefactor of University of Michigan Women.” Michigan Quarterly Review 2 (1963): 36. Print.

- Ding, Maoying. “Letters to Abby Turner, 1915–1950.” Me-Iung Ding Letters. Web. 15 Nov. 2016. <https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~dalbino/letters/mting.html>.

- Faerber, Karen Irene. “The Levi L. Barbour Scholarship for Asian Women.” Master’s thesis, Eastern Michigan U, 16 Nov. 1994. Print.

- Lake, Marilyn. “The ILO, Australia, and the Asia-Pacific Region.” The ILO from Geneva to the Pacific Rim: West Meets East. Ed. Jill Jensen. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. Print.

- Paisley, Fiona. Glamour in the Pacific: Cultural Internationalism and Race Politics in the Women’s Pan-Pacific. Honolulu: U of Hawaii P, 2009. Print.

- Semenza, Nevada. “China’s Great Need for Women Leadership Finds Its Answer in the Halls of Jinling, Cathay’s Edition of America’s Smith College.” China Press, 22 July 1931. Print.

- Ting, Evelyn Kay. “Me-Iung Ting x1916.” Web. 15 Nov. 2016. <https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~dalbino/letters/women/mting.html>.

- Waelchli, Mary Jo. “Abundant Life: Matilda Thurston, Wu Yifang and Jinling College, 1915–1951.” Order no. 3059344, Ohio State U, 2002. Print.

- Xiong, Rosalinda. Jinling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship. Singapore: Rosalinda Xiong, 2016. Print.