The University of Michigan in China

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

3. Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu: The University of Michigan’s First Chinese Students

Just 10 years after James Angell returned from his diplomatic work in China, the University of Michigan admitted its first Chinese students. In 1892, Kang Cheng (Ida Kahn) and Shi Meiyu (Mary Stone) traveled from Jiujiang on the southern shores of the Yangtze River to Ann Arbor to take the Medical School’s entrance exam. Four years later, they graduated at the top of their class and returned to China, where they opened schools, hospitals, and medical dispensaries. As China entered a period of political uncertainty at the end of the Qing dynasty, Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu became stabilizing forces in their community. They earned the respect of city elites and the poor alike, embracing a complex identity that was Chinese and Christian and Western all at the same time. They navigated among communities with startlingly different needs and expectations, from fellow missionaries and American congregations to Chinese Nationalist reformers, from government officials and military personnel to the local working poor. Over their lifetimes, Kang and Shi helped create a place of agency and independence for women in New China that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century.

A Michigan Missionary Alone in China

The story of Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu begins in Ypsilanti, Michigan, with a woman named Gertrude Howe. The daughter of a Quaker family, Howe grew up surrounded by calls to service and social justice. Her father was a staunch abolitionist, and Howe recalled her mother saying to her, “Gertrude, I want you to be something and to do something when you grow up” (Shemo 21). Although Howe enrolled in the Medical School in Ann Arbor, the calling to be a missionary interrupted her education. She joined the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) and made plans to travel to India. In the autumn of 1872, Howe made her way to Lansing, Michigan, to receive final instructions. As she gathered together with the other women of the WFMS, however, a telegram came through asking Howe to change her plans and start instead for China the next morning. Howe scrambled to consult with her family—reportedly, her mother was “aghast at this sudden change of plans,” but when the morning came, Howe left for China with her father’s blessing.

Howe and her traveling companion, Lucy Hoag, found life in Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, to be challenging in their first days. They opened a boarding school for girls, the first of its kind in the Yangtze Valley, but they had difficulty getting anyone to enroll. The city had only become an open-treaty port 10 years prior, and missionaries and foreign teachers were still treated with suspicion. Howe and Hoag “faced rumors that the real reason for their school was to collect the eyes of Chinese children for telescopes and their hearts for medicine,” and sometime during their first year in China, locals reportedly attacked and destroyed the school (Shemo 22).

Gertrude Howe as a young missionary. Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

While the school was eventually rebuilt and Howe was unharmed, it’s no surprise that she felt lonely and unmoored in Jiujiang. She “jokingly” suggested adopting a daughter to her Chinese language teacher, who took the proposition seriously. Her teacher did, in fact, know of a family with a daughter they couldn’t support. Howe stepped in and adopted Kang Aide, to whom she gave the English name Ida Kahn. Over the next decade, Howe would adopt other children, a move that let her create a family even within the strictures of the missionary community and helped her put down roots in China, where she lived until the end of her life.

One of Kang Cheng’s constant companions in the WFMS community was Shi Meiyu, the daughter of “impoverished gentry” who became language tutors for the missionaries and themselves eventually converted. Meiyu’s father, Shi Ceyu, became the first Chinese Methodist pastor in the Jiangxi province, and it was his idea to begin preparing his daughter for a career as a physician. He proposed to Howe that his daughter receive an education that would prepare her for an American medical school, and although she initially found the idea “startling,” Howe soon agreed to arrange English and science classes for Kang and Shi. Shi’s reaction to this plan is not recorded, but Kang must have been pleased:

When Aide was twelve, [Howe] had found a Chinese man who had traveled overseas and was willing to set up a marriage with his son. According to Howe’s later recollection, when she approached Aide about the match Aide “stamped her feet” and refused to marry anyone. She had decided to become a doctor, so she could “help Chinese women like the medical missionaries did.” (Shemo 34)

While contemporary medical programs such as the University of Michigan’s integrative medicine initiative find common ground between traditional and scientific medical practices, in the late 1800s, there was a considerable practical and philosophical gulf between traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine. Even America, at the end of the 19th century, was still slowly adopting Europe’s medical advances, such as germ theory. For their whole medical careers, Kang and Shi fought to normalize Western medical practices in China, and they voraciously read recent medical scholarship to keep abreast of new techniques and practices.

Education between Two Cultures: Late 19th Century

Life on the border between American and Chinese traditions made it difficult for Kang and Shi to integrate with other children their age. One issue in particular marked the two girls as different: they didn’t bind their feet. While various efforts had been made by the Qing dynasty and others to forbid foot binding, most upper-class and many middle-class girls at the end of the 19th century would still have had bound feet. Kang recalled that at one gathering,

the young girls hardly tasted their food, but looked us over from head to foot, especially our feet . . . Mrs. Stone advised me not to wear spectacles, for I attracted many remarks. I told her I was only too glad to draw attention from our feet. (Shemo 18)

In another anecdote, Shi was bullied by the other girls in the neighborhood, one of whom “barred her way to school, demanding that Meiyu bow to her own bound feet” (30). In later years, Shi Meiyu’s mother even unbound her own feet in support of her daughter, a process just as painful as the initial binding.

Howe also made sacrifices for her adopted daughter, living outside the compound that was reserved for foreign missionaries. Shi Meiyu described how, during the sweltering south-central China summers when other missionaries would retreat to foreign-only mountain resorts in Kuling, Howe chose to stay with her adopted children in “a little hut-like home in the hot foothills” (Shemo 27).

Shi Meiyu (left) and Kang Cheng as young women. Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

In 1892, when Shi was 19 and Kang was 18, they traveled to Ann Arbor to take the University of Michigan’s Medical School entrance exam. A Western university would have been, at this time, their only option: while China was beginning to reform its education policies, it would be some time yet before women could receive an equivalent medical degree. Gertrude Howe accompanied the two young women on their journey. The Chinese Exclusion Act (which had replaced the Angell Treaty) was still in effect, and Chinese travelers to the United States were often suspected of being laborers or prostitutes. When immigration officials challenged Kang and Shi, however, the two students had Howe to champion them. Howe drew on influential Methodists in Ann Arbor and contacts at the publication The Christian Advocate to help smooth the girls’ entry into the United States.

Shi Meiyu (left) and Kang Cheng as students. Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

After the rigors of immigration, Kang and Shi had to contend with the entrance exam. In those days, a college education was not a requirement for medical schooling, with the exam serving as proof of a student’s eligibility. The entrance exam covered a wide range of subjects, from US history to Latin—it’s not hard to imagine the pressure that Kang and Shi must have felt, having traveled around the world for one chance to make their career aspirations a reality, the two of them among the first Chinese girls to apply to a medical school in the entire United States. In one anecdote,

Dr. Kahn tells of the difficult entrance examinations and how when she was faced with this question on American history, “Who was the leader of the rebel forces at Gettysburg” that every bit of her cramming for those examinations had left her mind. “But wait!” she said, “Where had I read about the battle until I fairly smelled the smoke on the field and heard the cannons roar? Then everything came back in a vivid flash and I remembered reading Ida Tarbell’s ‘Life of Abraham Lincoln’ and I quickly jotted down ‘General Lee.’” (Shemo 45)

Both Kang and Shi passed their exams with high marks and began their lives at the University of Michigan.

For the first two years of school, Howe stayed in the United States, living with Kang and Shi to help ease their transition. While both women continued to excel in school, in an interview many years later, Howe recalled that “the terrible terrors of the laboratory” gave the two students sleepless nights. Shi herself said that “life in America was a different world to us and the Medical Language was a different language” (Shemo 46). In the face of such academic rigor and cultural transition, another pair of students might have clung together for support and, understandably, had difficulty engaging with the other students. Not Kang and Shi. After the first two years, Howe left them on their own to board with a woman named Mrs. Frost, who recalled them having many friends whom they would sometimes invite over for “a little Chinese feast.” The two wore American-style clothes, and in her junior year, Kang was elected as the secretary for her class (46).

Four years after being shepherded to the United States by Gertrude Howe, Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu graduated with distinction. Many accounts, in fact, place them as the top second and third students of their class (though none of the sources indicate who was second and who was third). On the day of their graduation ceremony, rather than wear a cap and gown, Kang and Shi wore traditional Chinese garments, Kang in a blue silk robe, Shi in pink. They were the first Chinese women to attend the University of Michigan, and there they were, receiving a diploma from James Angell while wearing symbols of their homeland.

Putting Down Roots at the End of the Qing Dynasty

Kang and Shi returned to Jiujiang in 1896, serving, as Howe did, with the WFMS. Howe and others suggested that the two graduates spend a few years training with established hospitals in Shanghai, but Kang and Shi rejected this plan, perhaps wanting to prove that their education had been preparation enough for the work of providing medical care. In any case, they didn’t waste much time—shortly after arriving, they opened a small medical dispensary for women. And despite concerns from the WFMS that the dispensary would have difficulty getting off the ground, three days after opening, four patients presented themselves for treatment. Soon Kang and Shi were running a thriving operation. They described one particularly difficult case in which a mother giving birth to twins had ceased labor after the delivery of the first child. The family sent for Kang and Shi, who were able to save the lives of both the mother and the second child, although the first child died. Once the mother had recovered, the family threw a feast for the two physicians and, in the evening, “[followed] them home with fireworks” (Shemo 50).

Shi Meiyu the year of her graduation, 1896. BMC Media Services records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Some of the challenges of opening a practice in Jiujiang came, in fact, not from the Chinese locals but from the missionary society. While neither Kang nor Shi took a salary for the first few years in order to repay school funding provided by the WFMS, when they did start receiving a salary, it was substantially lower than what their non-Chinese counterparts were making. But there was an even more visible inequality: they weren’t allowed to live in the nicely appointed missionary compound. The strict Chinese-foreign segregation was enforced even for Kang and Shi. In the coming years, this hypocrisy would become increasingly embarrassing for the WFMS as Kang and Shi’s prestige grew. Their very presence encouraged the missionary institution to reexamine its values and policies.

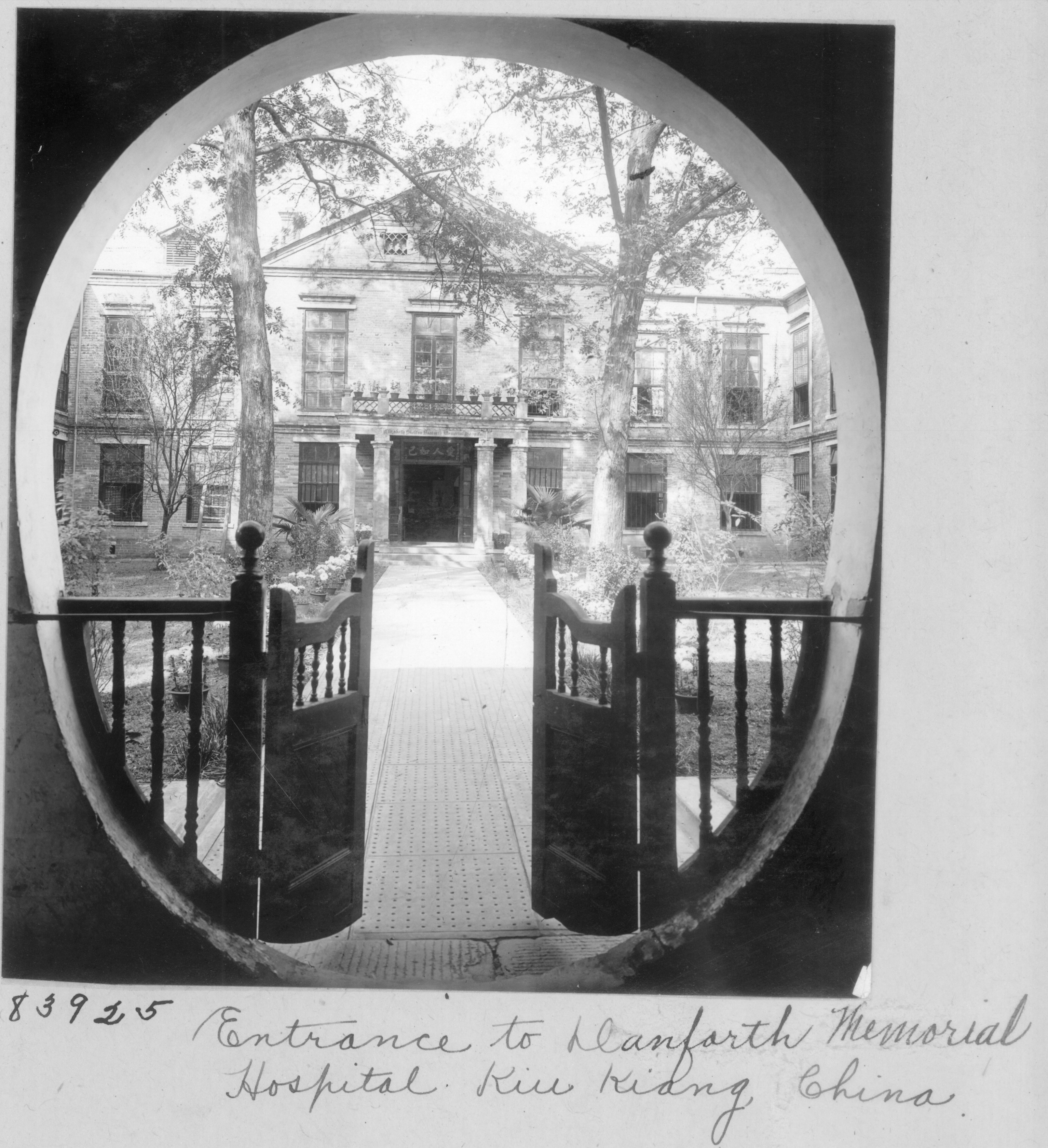

By 1898, Kang and Shi were already lobbying to expand their practice into a full-size hospital. Fundraising letters sent by Shi Meiyu described their current working conditions as “crammed full . . . fairly an oven,” and she was hoping “for signs or signals from the women of America to build our new hospital” (Shemo 61). With financial support from Dr. I. N. Danforth, a physician mentor Shi had met in Chicago, by 1900, the new building was complete, described as “airy[,] . . . plentifully supplied with comfortable verandahs” and full of modern appliances (62).

The satisfaction of opening the new hospital was short lived. When Kang and Shi returned to China in 1896, the political climate, though turbulent, welcomed them as ambitious women who might help revitalize what many saw, after the disastrous Sino-Japanese War, as a Chinese population sapped of strength. One famous scholar and reformist, Liang Qichao, even wrote an essay on Kang Cheng in which he praised her as a model of the “New Woman” of China. Just four years later, however, the Boxer Rebellion had gained enough momentum that Kang and Shi’s lives as missionaries in Jiujiang were threatened. With the slogan “Support the Qing, Destroy the Foreign,” by early 1900, Boxers began attacking and killing missionaries in northern China. The Qing government, caught between a shared antiforeign resentment with the Boxers and binding treaty agreements with those same foreign powers, was slow to condemn the attacks.

“Entrance to Danforth Memorial Hospital. Kiukiang, China.” Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

While the most violent expressions of the Boxer Rebellion remained in northern China, the movement continued to grow in central and southern China. By the summer of 1900, the threat had spread, and while the Qing governors-general remained in control of the cities, it was unclear how many officials sympathized with the Boxers. Kang and Shi’s practice, meanwhile, suffered: “Through fear our patients had dwindled away until we only had a few every day,” Shi wrote. Shortly thereafter, they were forced to abandon their new hospital entirely when the American consul ordered all women and children to leave Jiujiang. Howe, Kang, Shi, and many others boarded ships for Japan, where they would take refuge until the end of the year. Although the hospital itself remained unscathed during the uprising, Shi’s father died from wounds he sustained during an attack (Shemo 63). A letter from Kang written during this period shows her love and concern for her country:

Sometimes my heart aches so much for my people, and crying does not even relieve me, until I throw myself completely at my Savior’s feet, realizing that He also cares and will comfort His poor afflicted children everywhere. I suppose this had to come before a new China could be brought forth, but oh, at what a cost. (64)

Neither Kang nor Shi saw any conflict between their Christianity and their nationalism. And while this put them in the company of leaders such as Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, for whom Christianity was an avenue of reform and political advancement, Kang and Shi melded the two with no indication that one might diminish the other.

Diverging Paths: Shi Meiyu and Conflict with the Missionary Society

After nearly a decade of working as partners in Jiujiang, Kang and Shi’s paths diverged. A group of gentry in the province’s capital, Nanchang, invited Kang to establish a medical practice in their city. In 1903, Kang accepted their invitation, and although the two women parted on good terms, they would never again work side by side at a hospital.

Shi Meiyu remained in Jiujiang, now shouldering twice the workload. Her old mentor, Dr. Danforth, worried that the task would be too difficult alone and offered to find an American nurse who might be willing to help out. Shi refused. More important than her own health was her hospital’s autonomy as a Chinese-run institution. She felt “determined to present her hospital as a model of Chinese women developing a medical ministry without Western supervision” (Shemo 72).

The next several years would bring some significant life changes for Shi. Her sister, Anna, returned from studies in the United States to help Shi with the management of the missionary aspects of the hospital, despite having been diagnosed with tuberculosis. And the hospital continued to grow in fame, with Shi herself a draw for guests. One report mentions “one progressive official” who “wished his daughter to take a journey of 450 miles to see Dr. Stone for the inspiration she would receive.” Despite this reputation, Shi and her sister still lived outside the WFMS missionary compound in “a tiny rented native hut” (Shemo 74). In 1906, Anna succumbed to her illness. In less than a decade, Shi had lost both her father and her sister.

In the midst of this turmoil, Shi Meiyu received a blessing. Jennie Hughes, an American missionary who had fled to Jiujiang from the capital during the Boxer Rebellion, arrived to take over some of Anna’s duties, teaching classes and organizing the evangelistic outreach. Soon Jennie had moved into Shi’s house in Anna’s place, and there she would remain for the rest of her life as Shi’s companion and life partner. Dr. Danforth, meeting the couple years later in Chicago, said “the harmony—may I not say Christian love—existing between Miss Hughes and Dr. Stone is something worth going a long way to see” (75).

“In one of Dr. Stone’s wards. WFMS Hospital, Kiukiang. Danforth.” Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

Shi’s vision for Jiujiang and China wasn’t limited to the creation of a functioning hospital. While most missions taught English and religion classes, Shi started a nursing school too. At a time when infant mortality was high, Shi hoped that Western obstetrics could supplement traditional midwifery. She also trained her nurses in basic surgical skills. In the rare weeks that Shi and Jennie were away from the hospital, she had such faith in her nurses’ abilities that Shi trusted them to cover all of her ordinary duties.

The nursing program gave the women who joined agency and options. One anecdote describes a nurse, Ho Yin, who reversed traditional gender roles and supported both her fiancé and her brothers after their father passed away. Another anecdote recounts a man bringing his wife to the hospital hoping that Shi would certify the woman as mentally unstable in order to facilitate a divorce. Shi refused, and when the man abandoned his wife at the hospital, Shi offered the woman a position in the nursing school. The school and hospital became a “haven for women who needed an independent means of support,” providing an alternative to marriage and a safety net for those who needed it.

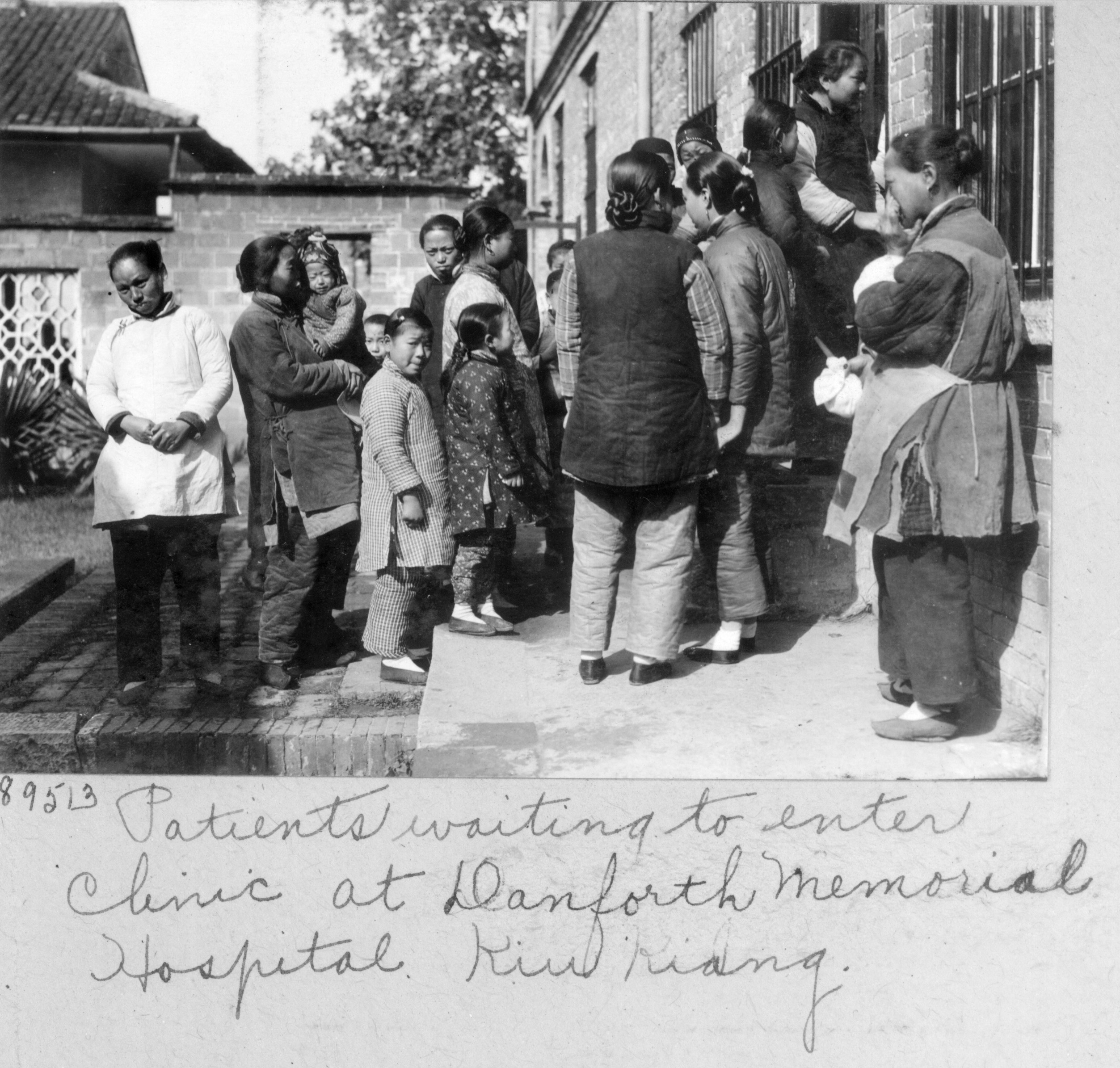

In 1906, Jennie and Shi traveled to the United States. Shi needed to have her appendix removed, but maybe even more urgently, she needed rest. She had been working at a feverish pace for more than a decade and was still reeling from the deaths of her sister and father. At the time, the Chinese Exclusion Act restricted the immigration of Chinese laborers. Entering the United States had become a nightmare for Chinese citizens; even those travelers exempted from the act often had to undergo “Kafkaesque drama” at Angel Island, where they might be interrogated by immigration officers intending to trick them into admitting that they were laborers. So when, as they landed in San Francisco, a tugboat approached their ship and the officer aboard asked for a Chinese woman named Stone, it is no surprise that Shi’s “heart was like lead” (Shemo 89). But instead of interrogating and deporting her, the officer told them that President Teddy Roosevelt himself, informed of Shi’s travel plans by the WFMS, had sent the ship for them directly.

“Patients waiting to enter clinic at Danforth Memorial Hospital. Kiukiang.” Courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church.

What began as a furlough for rest and recovery from appendicitis soon became a speaking tour of the United States. Shi and Jennie traveled across the country, speaking at colleges, churches, women’s groups, and social clubs in the hope of raising funds for their medical work. Soon Shi garnered a reputation as a charismatic, persuasive speaker. She adopted American slang, wore “a Chinese silk jacket and an American style skirt,” and spoke so passionately that “no one could resist [her] persuasive tones,” and “not once did she fail to get what she asked for” (Shemo 91–92). By the time her tour of the United States was over, Shi had raised enough money to expand the medical practice considerably and build herself and Jennie a proper house.

Their practice continued to expand in the following decade: the hospital developed its nursing program, and the mission’s Bible school for girls grew, under Jennie Hughes’s direction, to include what was essentially a full high school curriculum, one that was capable of training young women to the point of eligibility for higher education. But their practice expanded too much for the comfort of the WFMS, and by 1920, some friction developed between the group and Jennie Hughes over the kind of education students at the Bible school should receive.

This tension, combined with continued income inequality between foreign and Chinese workers, proved too much, and in the early 1920s, both Shi and Jennie resigned from the WFMS, resolving instead to create an independent mission that could live up to their ideals. After several years of fundraising, they founded the Bethel mission, a compound in Shanghai that included a hospital, a nursing school (which attracted as many as 200 students a year), a high school, and a chapel.

Here they worked until World War II. When the Japanese began bombing Shanghai in 1937, Shi Meiyu and Jennie Hughes happened to be traveling in northern China. There they received telegrams urging them to not return to Bethel but to flee instead to Hong Kong. They followed this advice and, in the end, sailed all the way from Hong Kong to Pasadena, California. Shi and Hughes would live together in the United States through the end of the war and for the rest of their lives, overseeing the reconstruction of the Bethel mission from afar. Jennie Hughes died in 1951, and Shi Meiyu followed three years later, passing away in 1954.

Kang Cheng: An Accidental Diplomat at the Birth of a New China

Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu parted ways in 1903, when Kang, on the invitation of the city elite, moved to Nanchang with Gertrude Howe in order to start a new medical practice. There Kang found a much different culture than the one she’d left behind in Jiujiang. While Nanchang was the capital of the province, it was also far less exposed to Western influence than Jiujiang, which had been a treaty port city since the middle of the 19th century. She recalled a visit to the city back in 1898 during the swelling antiforeign sentiment before the Boxer Rebellion. A crowd had surrounded her and her traveling companion, an American WFMS missionary, and while her American friend was allowed through, the crowd threw stones at Kang and taunted her with jeers of “A foreigner! A foreigner!” When she tried to enter a house to escape the barrage, she found the gate barred against her. Luckily, more sympathetic members of the crowd helped her escape (Shemo 103).

Things weren’t quite so bad when Kang returned to Nanchang in 1903. She established a small medical dispensary with funds from the local elite, and yet, for all the interest the gentry and reformists showed in Kang, there was an equal disinterest from the city’s ordinary citizens. This disparity is visible in the numbers: “In her first year, Kang saw just over 2000 patients, as opposed to the more than 12000 that Shi and her nurses treated in Jiujiang” (Shemo 109). And Kang herself gave voice to the frustration of dealing with a skeptical population:

Can you imagine your sensations if patient after patient to whom you were called were clothed in their best official garments and were then laid out . . . ready to breathe their last? That was the situation I faced in this huge old town of Nanchang simply because it had no people who believed in Western medicine. No wonder my servant said I had no talent, and I was ready to believe it too, for how could I revive these dying women? (109)

Even when the number of patients increased, Kang’s first years in Nanchang were marked with anxiety and financial troubles. Gertrude Howe and her sister gave Kang what money they could, and Kang even sold “her little stock of jewelry” to help pay for the expensive rent and the medicines she distributed daily. In a later written work, she described those years, saying, “The anxiety as well as the financial hardship was almost too much to be borne” (Shemo 110).

Gradually, however, support for Kang’s work grew among the gentry and the Methodist missionary community. Some members of the gentry purchased the land to build a hospital in addition to the dispensary—a property within the walls of Nanchang itself and the only missionary community with that distinction. And a short time later, a visiting Methodist bishop was reportedly dismayed to find a physician of such renown living inside the crowded dispensary. Returning home, the bishop diverted $5,000 to build a home nearby for Kang and Howe.

Growth came more rapidly in the 1910s. Kang and Howe, like Shi several years before, conducted a fundraising tour of the United States, and they returned to Nanchang to find their hospital completed. The revolution of 1911 and the overthrow of the Qing dynasty inspired in many citizens the hope of reform and the prospect of building a new Chinese Republic. Western ideals became in Nanchang both more familiar and more favorable. When the political philosopher, activist, and architect of the revolution Sun Yat-sen came through Nanchang in 1912, Kang had enough prestige among the elite to throw a banquet in his honor. Sun Yat-sen himself observed Kang’s work and donated some money toward the running of the hospital. In the months after receiving such a resounding seal of approval, Kang experienced a sharp upswing in the number of patients interested in her hospital.

The idealism of the 1911 revolution gave way to a period of uncertainty at the end of the decade and into the 1920s. The dream of a unified republic failed to materialize, and in its place came a long period of warlordism, during which the country fractured into provinces and cities under the control of independent leaders. Luckily for Kang, the governor of Nanchang was sympathetic to her work. Elsewhere, Nationalist sentiment continued to grow as the Guomindang (GMD; Kuomintang) Party, founded by Sun Yat-sen, sought to unify a splintered China. Foreign elements, including missionaries and Chinese Christians, were branded as imperialists. Kang found herself having to balance a series of complicated loyalties to her faith and church, to the local government and the soldiers who needed medical care, and to the GMD troops looking to end the era of warlordism.

Because of these complexities, Kang was forced to compromise, letting soldiers rest in her compounds and allowing her female nurses to treat male patients, an issue that in the past had caused friction between her and the WFMS. The pressure on her to perform under politically fraught circumstances also increased. One anecdote describes one of the highest-ranking officials in Nanchang summoning Kang to treat a member of his family. The ailing woman had already been seen by practitioners of traditional medicine, who had refused to treat her due to the severity of her illness. “The least mistake in diagnosis, and she would be dead,” wrote Kang. “Fear filled my heart.” She too was unable to make a clear diagnosis, but under pressure from the official and his family, she prescribed some medicines anyway: “I thought how incapable I was, and how little I knew! I wished I had never tried to be a doctor” (Shemo 237). Despite Kang’s reservations, the woman made a startling and rapid recovery, and thereafter Kang was trusted to treat other members of the family.

When she wasn’t directly helping the wounded, Kang offered her hospital compound as a sanctuary. Two stories high with a central courtyard, a green lawn, and a garden of fruit trees and flowers cultivated by Kang herself, the compound served as a shelter for “terror stricken women, men, and children” fleeing from the combat between warlords and the Guomindang. While soldiers looted many other homes, they left Kang’s untouched, perhaps due to her connections with the elite of Nanchang or because of her connection to a foreign mission. Despite anti-imperialist sentiments, combatants were reluctant to provoke armed responses from foreign powers. Kang flew the American flag above her hospital, saying, “You may speak all you wish of extraterritoriality, but if the ‘Stars and Stripes’ could save these poor women and children from being terror stricken, then I am glad we could borrow this protection” (Shemo 241).

Kang took extra steps toward diplomacy by inviting high-ranking officers and generals from both sides to banquets at her house so that they might have “a more favorable (or less unfavorable) view of Christianity” and “leave us alone.” Kang’s house and name became “a talisman throughout the city,” a byword for safety. When, in the autumn of 1926, the Guomindang finally took control of Nanchang, Kang retained her connections with the party. Officers still came to dinner at her house and, she hoped, “would go away feeling decidedly more friendly, and not so cocksure about the evils of Christianity” (242).

Kang Cheng, or Ida Kahn as she was known in America, during her years as a physician. Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee Records, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

The peace didn’t last. In the spring of the following year, GMD troops attacked American, British, and Japanese embassies in Nanjing. In retaliation and to provide cover for fleeing civilians, American and British destroyers fired on the city. The resentment of foreigners among Chinese soared. A month passed until Kang and Gertrude Howe (by now suffering from Alzheimer’s) woke up one morning to find their mission compound deserted. All foreign missionaries, with the exception of Howe, had arranged to leave Nanchang in secret. No one had told Kang. A servant came with a note explaining what had happened and that the plan was to have been “strictly confidential among the foreigners” (Shemo 244).

To the missionary community, Kang must not have been “American enough” to take into confidence, and the lack of trust must have felt like betrayal. Even more difficult to forgive would have been the abandonment of Howe. Knowing that Kang would never leave her adoptive mother, the American consul and other missionaries chose to leave Howe behind rather than invite Kang. Kang herself described the experience: “We woke up one morning to find that all our missionaries had left, apparently without sending one word to us. I can never describe the pain of that moment.”

Being left alone, without the protection of the foreign community, put Kang and Howe in considerable danger. Other missionary hospitals were burned and looted; “Chinese pastors suffered beatings and kidnappings” (Shemo 245). Nonetheless, Kang remained in Nanchang, and while her home was never destroyed, soldiers invaded the compound, using her lawn as a drilling yard and stripping her carefully planted garden of fruit. She was, in other words, harassed by the same Nationalist army that had once dined at her home and been treated at her hospital. Officers lectured her and her nurses, calling them “the running dogs of foreigners.” Kang’s nurses, however, refused to applaud, and Kang herself stood up to defend herself, applying Sun Yat-sen’s “Three Principles” to their medical work, arguing that “we are true Nationalists” (245).

For the next several years, even after Howe’s death in 1928, Kang protested vocally against the threat of the Chinese Communist Party, which was now taking refuge in her province, and later against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. She wrote essays calling for aid from the international community even as she struggled to maintain funding for her hospital in the embattled Jiangxi province.

By the end of 1931, Kang herself had fallen gravely ill. One missionary described cancer in the abdomen, “which had spread down into her legs until one of her thigh bones broke.” Others described liver disease and kidney failure: “It is clear that Kang was in a great deal of pain before her death” (Shemo 253). Still she managed to treat others up until the end, even being carried up and down stairs to visit patients. When Kang realized that she was dying, she called for Shi Meiyu, who came to visit one final time. The two “sang hymns and other songs they had learned as children” (254).

A Legacy of Selflessness

Their names are no longer widely known, and their stories are not widely taught. And yet Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu have left a clear legacy: in China, they introduced a whole province to Western medical practices, began a modern nursing education system that continues today, inspired reformists to imagine new roles for women as China shed its dynastic traditions, and personally tended to many thousands of the sick and injured in Jiujiang and Nanchang.

At the University of Michigan, Kang and Shi have left a lasting, if indirect, mark—they met Levi Barbour, a regent for the University, and their example inspired him to create the Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women, which will be the focus of the next chapter.

Works Cited

- Burton, Margaret E. Notable Women of Modern China. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1912. Print.

- Izant, Edwin. “Excerpts from a Talk Honoring Gertrude Howe.” Lansing, MI: Central Methodist Church, 1947. Print.

- Shemo, Connie Anne. The Chinese Medical Ministries of Kang Cheng and Shi Meiyu, 1872–1937: On a Cross-Cultural Frontier of Gender, Race, and Nation. Bethlehem: Lehigh UP, 2011. Print.