Coming of Age: Teaching and Learning Popular Music in Academia

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Popular Music Pedagogy: A Look Into Curricular Possibilities

The aim of this chapter is to share pedagogical possibilities for popular music curriculum in middle and high school music classrooms. To this end, I will share my own ideas and those of my students drawn from an undergraduate course at Oakland University—“Teaching Music in the Twenty-First Century II”—that focuses on digitally based projects and popular music. This class comes at the end of the methods coursework that includes elementary, choral, and instrumental methods as well as music for learners with exceptionalities.

Context Of The Classroom

All the methods courses in our program (as well as classes in educational psychology and music education philosophy) share a constructivist approach.[1] This student-centered approach that values musical problem solving, learner agency and autonomy, and hands-on mindful collaborative experiences is central to the ways we interact with students and how we prepare preservice teachers to interact with their future students. This section does not aim to be an exhaustive description of constructivism; however, it will provide a brief overview of constructivism, highlighting characteristics that will inform the examples provided in the following sections.

Constructivism

Constructivism, a vision of how people learn, values the notion that people must construct their own understanding of their world and their role in it. Not a method but rather a theoretical frame for human learning and interaction (Fosnot, 2005), constructivists posit that learning must be experiential with meaning making as a synergistic interplay of thinking, doing, and social interaction in holistic contexts: “The theory describes knowledge not as truths to be transmitted or discovered, but as emergent, developmental, nonobjective, viable constructed explanations by humans engaged in meaning-making in cultural and social communities of discourse . . . A constructivist view of learning suggests an approach to teaching that gives learners the opportunity for concrete, contextually meaningful experience through which they can search for patterns; raise questions; and model, interpret, and defend strategies and ideas” (p. ix).

A Vygotskian scholar, Smidt (2009) suggests that “we are all the sum total of our experiences and our interactions with the people and the ideas and the cultural tools we encounter throughout our lives” (p. 10) and that “for Vygotsky, all learning was social” (p. 14): “He meant social in the sense that ideas and concepts are often mediated by more experienced learners; that learning takes place in a context which may well be social in origin; that learning builds on previous learning; and that learning takes place primarily through cultural and psychological tools” (p. 15).

Bruner (1966; Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976) is credited with coining the term “scaffolding”—that is, the many ways learners are supported in their learning by more experienced others.

Agency

Learners of all ages and in every capacity must have a sense of agency—that is, the “ability to make things happen in [their] immediate environment” (Smidt, 2009, p. 2). Fostering agency in the classroom might occur when a learner senses that her active engagement and “musical say” (Davis, 2011) will inform her own—and contribute to her peers’—process and outcomes. Wiggins (2015, 2016) writes extensively regarding musical agency, or the ways that learner agency plays out in music classrooms or communities: “Learning requires initiative and intent on the part of the learner. To be willing and able to enter a learning situation, learners must have a sense of personal agency—that is, a belief in themselves, a sense that they have the capacity to engage, initiate and intentionally influence their life circumstances (Bandura, 2006) . . . They must believe their ideas will be valued” (Wiggins, 2015, p. 22).

It is a process to learn to support students’ agency. Most of us have experienced more directed and less collaborative styles of teaching and learning in our own schooling. For this course, an explicit study of student-centered practices in our projects included the unpacking of constructivist ideas so that we can better reflect, design, and assess our own progress as constructivist preservice teachers and teacher educators. We affirm this goal: “When the classroom environment in which students spend so much of their day is organized so that student-to-student interaction is encouraged, cooperation is valued, assignments and materials are interdisciplinary, and students’ freedom to chase their own ideas is abundant, students are more likely to take risks and approach assignments with a willingness to accept challenges to their current understandings. Such teacher role models and environmental conditions honor students as emerging thinkers” (Brooks & Brooks, 1993/1999, p. 10; emphasis added).

Application of Theory to Practice

For the purposes of this chapter, I will focus on key characteristics of constructivism that were salient in this course and that are demonstrated in the examples that follow.

Opportunities for choice that support learners’ interests will enable students to connect to and creatively invest in a new learning experience. Agency is fostered when students can choose their topic and their means of musical expression within a framework of curricular goals. Student-centered schooling takes “its cues from young people’s interests, concerns, and questions” (Zemelman, Daniels, & Hyde, 2005, p. 12). The nature of this dual approach—developing a rigorous curriculum while creating a space for choice and expression—was often discussed throughout the university course and supported by Brooks (2002) and Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde (2005). They challenged us to find essential questions that could support developing physical skills, conceptual understanding, and the taking of risks and promote collaborative and creative thinking: “Knowledge depends on questions, and the process of coming to ‘really know’ something entails revisiting the essential concept in new settings, under new conditions, and with the parameters often enough to challenge one’s own thinking” (Brooks, 2002, p. 20). In considering the design of lesson plans or units, we revisit musical dimensions through new parameters of digital projects and popular musics (here, for their expression in a school setting) that challenge learners to stretch musical boundaries or skillsets in new ways—to “help students connect their current ideas with new ones” (p. xi). Opportunities for choice in these contexts allow learners to take the lead as the “more knowledgeable other” and to find ways to make “acute discriminations and broad connections” in a new context (Reimer, 2003).

Students will enter and make meaning socially through their shared experiences and individually through the lens of their unique prior experiences and worldviews: “Our prior life experiences frames our view of the world and, in many ways, determines how we will choose to act and react in new experiences. This provides the basis for multiple perspective—that each of us understands the world a bit differently because we interpret new experience through the frame of our prior experience” (Wiggins, 2015, p. 8). As teachers honor students’ prior experiences and create opportunities for students to expand and develop musical interests and ideas, a sense of agency and musical independence can thrive.

A constructivist vision of learning honors the notion that “all knowledge is socially constructed. Social interaction is an essential ingredient of the learning process,” with scaffolding at the core of peer and/or teacher interaction (Wiggins, 2015, p. 14). Collaborative projects allow students to better understand the contributions of others and might enhance the sense of musical community in the classroom, much like the ensemble experience: “In a genuinely democratic classroom, children learn to negotiate conflicts so they work together more effectively and appreciate one another’s differences. They learn that they are part of a larger community, that they can gain from it, and that they must also sometimes give to it” (Zemelman, Daniels, & Hyde, 2005, p. 20).

Because learning is socially and individually constructed, students must have opportunities to construct their own understanding. Characteristics of these experiences include the following:

- People are best able to construct understanding when new information is presented in a holistic context—one that enables them to understand how parts connect to the whole.

- Learners need to understand the goals of the experience and have sufficient grounding in the processes and understandings necessary to achieve the goals.

- The ideal learning/teaching experience enables learners to engage in the solution of authentic problems, rooted in authentic contexts. Good problems are structured in ways that enable learners to find and seek solutions to new problems. Problems for learning should be designed in ways that will provide multiple points of entry and invite multiple solutions—and the various solutions should be considered and valued for their uniqueness, creativity, and originality. (Wiggins, 2015, p. 25)

The notion of musical problem solving is at the core of our pedagogical approach in this course and across the coursework in our teacher education program. Preservice teachers experience musical problem solving in their university methods courses and are expected to design musical problems for their future students. Rather than interacting with a teacher for what to do or how to be musical, learners themselves engage with musical ideas and processes that will develop their own musicianship (Blair, 2009).

Curricular Possibilities

The ideas noted previously are central to the course “Teaching Music in the Twenty-First Century II.” Together, the students and I focus on innovative practice for middle and high school musicians within digital and popular music contexts. The preservice teachers are challenged to create a space where their future music students can discover ideas and stretch boundaries with a freedom to pursue musical projects with a wide range of choices yet still provide the groundwork and scaffolding that will enable student success. Preservice teachers are encouraged to explore big ideas and essential questions while getting to the details needed to support specific musical problems and contexts. We reconsider musical experiences in contexts that are meaningful and relevant with pedagogical goals that foster a collaborative social environment.

Brooks’s (2002) Schooling for Life: Reclaiming the Essence of Learning urges students to question the nature of learner choice/agency within a curricular frame, with goals that include immediate skills and understandings but that might reach beyond to more essential questions. Brooks suggests, “A good education . . . is a system of opportunities for students through which they build the foundational skills of an intellectual, ethical, aesthetic, and physically fit life that they can both use in the present day . . . and transfer to their future” (p. 13).

As with most methods classes, exemplary models are presented with full classroom engagement followed by discussion to unpack the pedagogical strategies demonstrated explicitly and implicitly. Instruction is proposed as a bridge that connects previous experiences with new experiences, allowing students to function successfully within their “Zones of Proximal Development” (Vygotsky, 1978), where students perform—with support—on the outer boundaries of felt zones of competence and confidence. Dewey (1916) offers insight to this delicate instructional balance: “A large part of the art of instruction lies in making the difficulty of new problems large enough to challenge thought, and small enough so that, in addition to the confusion naturally attending the novel elements, there shall be luminous familiar spots from which helpful suggestions may spring” (p. 157).

As noted previously, this course aims to explore ways to study popular music for its own value and to pursue a pedagogy that values a fluid blend of formal and informal ways of learning and expressing musical ideas. To support these ideas and to explore models, the preservice teachers consider the work of Allsup (2011), Davis (2005), Green (2005), Ruthmann (2007), and Williams (2014) to broaden their pedagogical landscape. Students have also had the opportunity to attend a Little Kids Rock[2] workshop as part of another course.

Thus the preservice teachers are required to design extended general music units for middle or high school students that include the musical processes of listening, performing, and creating while learning themselves how to balance learner choice with musical outcomes. The course provides a series of projects that inherently foster a continuum of choice within a curricular frame. Class projects include creating

- a “musical journey” in any digital format to share their musical histories;

- a group iPad cover of a popular song;

- a GarageBand recording and composition project;

- a lesson to scaffold any part of producing a cover or GarageBand project;

- a flipped lesson[3] to support any of the lessons already created;[4]

- a popular music unit that can draw on a wide range of musical ideas and skills (for example, riffs and hooks, sampling, mash-ups, style, covers, dance genres, harmony/chords, genre crossing/blending, multimedia, YouTube artists [Postmodern Jukebox, Boyce Avenue, Pomplamoose], and so on); and[5]

- an interdisciplinary unit that includes another arts discipline (students read Barrett, 2001; Wiggins, 2001; Wiggins, 2015).

The following curricular examples demonstrate some of these ideas. The characteristics of constructivism noted earlier are evident here in the musical problem solving, opportunities for choice and learner autonomy within a scaffolded pedagogical environment, collaborative and creative thinking, and experiential learning within a space that honors multiple perspectives and entry points. We hope these examples will offer ideas for curricular possibilities for the unique students in your own classrooms.

“Mas que Nada”: Listening, Performing, and Creating in a Popular Music Context

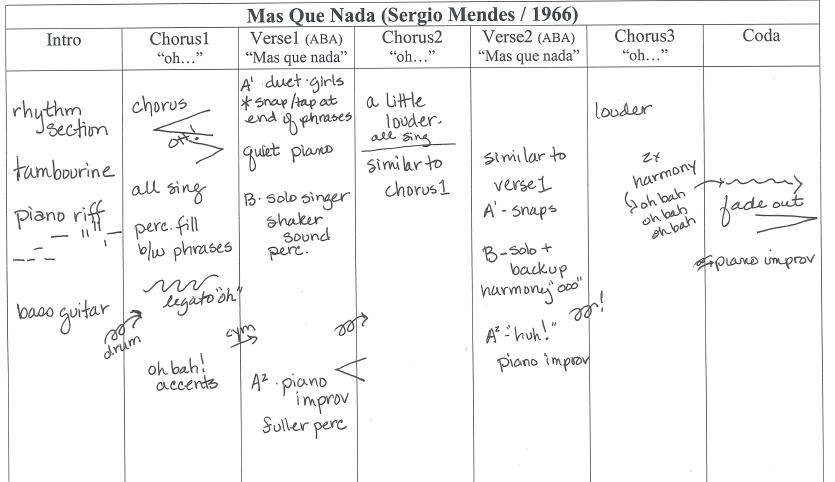

I created this set of lessons as a workshop for International Society for Music Education (ISME; VanderLinde, 2014) using “Mas que Nada” by Jorge Ben Jor (http://jorgebenjor.com.br/novo/) and popularized by Sergio Mendes (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qK631u3d_n8). We begin with the Mendes version because it is closer to the sound world of popular music and provides a closer schema connection for young learners (Dewey’s “luminous familiar spot,” 1916). The lessons begin with melodic contour in order to scaffold students as they figure out the differences between the singable verse and chorus, followed by a form chart that organizes the verses, choruses, intro, bridge, and coda. A “what else do you hear?” chart (Wiggins, 2015, pp. 173–181) extends the musical problem so that students can learn to listen and collaboratively describe (in their own words, providing for multiple entry points) what they hear and how it informs the form (see Figure 1).

Students then continue listening to other examples of this piece: the original by Jorge Ben Jor (http://jorgebenjor.com.br/novo/), followed by covers by Al Jarreau (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-gyskWUty4) and Dizzy Gillespie (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zeOt8WzGEAU), all of whom bring their own musical strengths to their renditions and adjust the form slightly—which, of course, students are asked to “figure out,” along with the requisite “what else do you hear?” The final listening example is performed again by Sergio Mendes some forty years later, this time joined by the Black Eyed Peas (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tfa6fRjPlUE). The form is doubled, and students are asked to figure out the expanded form and describe what the Black Eyed Peas contribute to this version (see Figure 2).

Form chart for “Mas que Nada,” performed by Sergio Mendes.

Completed chart demonstrates typical student comments.

By now, the students have moved from an initial inquiry of melody and form to include a wide array of musical dimensions (see Figure 3).

Finally,[6] students are invited to use the ideas of these composers, arrangers, and performers—and to draw on their own musical strengths—to work collaboratively to create a cover of “Mas que Nada.”[7] An alternative assignment could offer students the opportunity to create a digital cover in GarageBand or to use a riff from one of the versions as a sampling project.[8]

Allison Vernon: Scaffolding a Cover Project

Making covers is a popular project in many music courses, but I (Allison) wondered how we could scaffold that experience for students who have little or no knowledge of the musical concepts behind a song. Starting with the goal in mind (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), I knew I wanted students to be at a level of competence with the technology and the musical concepts that would enable them to create their own covers or even record an original composition. The final project at the end of this unit would give the students ample opportunities to make creative decisions for themselves and to choose what medium they would want to use.

In an ideal classroom, each student would have access to her or his own iPad or keyboard. After sufficient experience with melody and an introduction to the concept of chords, the students would listen to a piece of music that has limited chords but with changes that are easy to hear. Sam Smith’s song “Stay with Me” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pB-5XG-DbAA) meets these qualifications and is a popular song that most students would know.

In the first lesson, the students’ goal is to create their own lead sheet. They would work in pairs with a copy of the lyrics and notate where they hear chord changes. Then, using the smart keyboard function in GarageBand, they will figure out which chords fit into each spot. The smart keyboard function is ideal because the chords are easy to hear under the keyboard setting and there are limited options, so the students still must do some listening work to figure out which chord fits where, but there are not so many options that they will feel overwhelmed.

After completing the lead sheets, the students will have an opportunity to create their own cover of “Stay with Me,” which would have been used previously to discuss melody; it has an easily singable range and only uses notes in the diatonic scale. For this part of the unit, their choices are limited to specific musical apps on the iPad. GarageBand is highly recommended for ease of use, but other apps[9] such as WI Orchestra, Progression, Chordica, and so on can be used to create the harmony section. Students should also employ percussion apps and their voices to add the percussion and melody.[10]

The final aspect of the unit comes with many more opportunities for choice, supporting learner agency as students develop skills and become more confident in their abilities. The goal of the final project is to allow students some creative license with a musical composition (either a cover or their own composition) and then record their piece into GarageBand.

To efficiently scaffold their experience with recording into GarageBand, I will use a flipped lesson. Students will watch a short presentation on how to edit the chords in smart instruments and then record a chord progression as homework and upload it to the class SoundCloud page (http://soundcloud.com).

Once the students have some actual experience recording in GarageBand, they are prepared to create their own recording. I like this project because students who have experience singing or playing an instrument can use those skills, but students who have little or no experience with either of those mediums can use the iPads to create a composition that is equally meaningful and relevant.[11] This unit allows students to express their own musical voice within guided parameters with a final goal that is achievable with the appropriate scaffolding by the educator.

Alexander Walker: Popular Music That Explores Social Justice

In this unit, students will explore several examples of popular music that reflect a particular social justice stance. The students uncover and discuss uniquely musical features of the music and examine the historical/cultural situation in which the music arose. Ultimately, they will determine how the two are connected. The unit starts out using the iconic American musical artifact “We Shall Overcome.” It begins with the class listening several times to the original Pete Seeger recording (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJUkOLGLgwg), discussing initial reactions, and constructing a form diagram (verse, chorus, etc.).

Next, the students will read a brief Library of Congress article (see Appendix A) about the song and its unique place in American history, specifically during the civil rights movement. Students will also watch a video of Joan Baez singing the song at the 1963 march on Washington (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3VhgJC2M1Y). Discussion should address the musical, lyrical, and other features of the song that made it so popular, viewed through the lens of its cultural context.

To engage interactive meaning making, the students will then perform an in-class cover of the song. Students can use iPads, voices, or any instruments available, including drums or body percussion. The objective is to give students the choice—with our resources, what can/should we use?

Finally, the group watches or listens to the Diana Ross performance of the piece (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yx89KLkiIQ); students can listen while filling out a Venn diagram with similarities and differences. Class discussion can address essential questions: What is different here? What are the gains and the losses in this version? Does it change the attitude or message? How do the musical choices affect that?

In the next lesson, students will discover how contemporary popular music can reflect social issues and present them in a compelling way. This lesson utilizes the song “Americano” from Lady Gaga’s 2011 Grammy-nominated album Born This Way (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fHGKG9dyTKI).

After listening once as a class to garner initial reactions, the students use a “workalong” sheet and continue through the rest of the lesson individually using iPods, computers, or phones/headphones to listen to the music as they complete the worksheet (see Appendix A). Students are guided to identify and describe their initial reaction to the song, construct a basic form diagram, and analyze the song’s lyrics (including translations), paying attention to social issues presented. It also includes contemporary musicological research; for example, they will read a portion of an interview with the song’s producer to learn that the song was written in the days after Proposition 8 was repealed in California, which brings deeper meaning to (and explains the genesis of) many of the song’s lyrics (https://play.google.com).

Students need time for class discussion to discover each other’s opinions on the song and, more important, how everyone thinks the music and the social message work together—that is, what was the song’s purpose and does it achieve it? The teacher can mention some critical reception of the song: good beat/production, bold house/mariachi fusion, bad Spanish accent, and mediocre lyrics.

The final lesson of the unit is where the real opportunities for choice occur. The previous lessons explored musics that reflected a social stance, and students examined how exactly the music achieved that end. The logical assessment here, then, is to have students now employ those tools via a composition project. In small groups, students will compose a song in a popular style that clearly articulates a social position.

I envision this beginning by having the whole class brainstorm ideas. Students must first compose the song with lyrics, melody, and chords. The teacher provides scaffolding by reviewing the musical product thus far with the students, and then students can extend their musical ideas by producing the song in GarageBand. The song must be sung, but students can use autotune or vocal effects (especially if they are making a statement of some sort).

If the students hits a compositional “roadblock,” there are myriad examples of popular music that articulate a social position: “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan; “Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young; “A Change Is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke; “Strange Fruit” sung by Billie Holiday; “The Fear” by Lily Allen (explicit); “Primadonna Girl” by Marina & the Diamonds; “Royals” by Lorde; “Concrete Jungle” by Bob Marley; and “War” by Edwin Starr.

The teacher can offer some of these pieces, asking, “What is their message? What musical ideas do the artists use to achieve their message? Is it the style? Production? Lyrical constructs (simile, metaphor, etc.)?” Studying an exceptional musical construction in one or more of these songs could also be an intermediary lesson, revealing a compositional technique to the students.

A sharing of songs in class, on a school YouTube channel, or school radio station (with student permission) would be an appropriate culminating event.

Halla Hilborn: Music in Advertising

I (Halla) would begin the discussion of this topic by asking students to consider why music is so prevalent in advertising and to think about the different ways it is used (see Appendix B for advertising principles and commercial resources).[12] After some brainstorming and looking at examples, we would move to these categories and note the definitions for each one:

- Entertainment—engage the attention of audience (in a good or bad way)

- Example: Mountain Dew, “PuppyMonkeyBaby,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ql7uY36-LwA

- Structure/continuity—ties together images or narrative to provide continuity

- Example (images): Apple, “Save Time,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SHMbzEvxIo

- Example (narrative): Android, “Rock, Paper, Scissors,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UYxpX3N20qU

- Memorability—help audiences remember the product thereby increasing their probability to purchase

- Example: Kit Kat, “Give Me a Break,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0nkcVz1mad0

- Lyrical language—conveys a verbal message in a nonverbal way through use of poetic appeal

- Example: ASPCA, “In the Arms of an Angel,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjZ5dld2qHs

- Targeting—use of a musical style that is well liked and relatable to the product’s demographic

- Example: Chevy, “Like a Rock,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMs4X2GOZkw

- Authority establishment—expert testimony or endorsements; use of celebrities to appeal to audience

- Example: M&Ms, “Zedd and Blacc Singing in the Studio,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZELmYM0oM1E

With the scaffolding of this whole group discussion, students will now work in small groups to explore additional examples, determining the category for each. These include the following:

- Microsoft, “Women Made,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48m24w5MIkQ (structure/continuity)

- Kia, “The Truth,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjnFWcr6s3A (targeting—luxury as opera and authority establishment)

- Coca Cola, “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ib-Qiyklq-Q (memorability)

- Honda, “New Truck to Love,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogXjiFMtVyI (entertainment)

- Volkswagen, “Darth Vader,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGZNocni6zE (entertainment and continuity)

- Chrysler, “Imported from Detroit,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SKL254Y_jtc (authority establishment)

In the next lesson, we will explore the elements of advertising that are needed in a commercial. Students are asked for ideas about the kinds of things advertisers need to consider before making a television commercial. Explain that for every product, the commercial should

- have developed and organized a clear concept,

- know the target audience, and

- make an impression.

Every ad should also follow the attention, interest, desire, and action (AIDA) model (see Appendix B). Students will reassemble into their small groups from the previous lesson and watch some of the videos. As they are watching, ask the students to think and discuss how the commercial uses the advertising principles described previously, answering questions such as “What is the concept?” “Who is the target audience?” “How does this make an impression?” and “What purpose did the music serve in the commercial?” After each video, students will share their ideas with the class.

Next, students will watch the videos again and describe the songs used in the commercials with musical terms—for example, how the elements of texture, mode, melody, dynamics, tempo, mood, and style play a role in the overall message the commercial is trying to convey. As the discussion progresses, state that studies show consumers associate the major mode with pleasant and happy feelings and that faster tempos make consumers feel positive.

Here are some additional videos to use:

- Oreo, “WonderFilled,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFsZ6BO4LU0

- Hyundai, “First Date,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-R_483zeVF8

- Pepsi, “Monks,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Br0panORnWU

In the next lesson, students will work again in small groups, with each student having a classroom iPad with GarageBand on it. Explain that students will compose the music to accompany the Coca Cola “Catch” commercial (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2nBBMbjS8w). Remind them to consider both the roles of advertising and the ways that musical dimensions will play a role in expressing their ideas. Have the video playing continuously (silently) in the classroom while the students are working.

Once students are finished, each group will share their composition for the commercial. Allow the class to discuss how the group’s composition utilized music and advertising concepts. Finally, after all groups have finished presenting, play the commercial with the original music and have students discuss the musical concepts that the original utilized.

After this activity, students can take on the project of creating their own commercial, either individually or in small groups. The students will need to create a product and idea for the commercial. They can do this using iMovie and still images or by filming their own commercial. Next, they would have to either compose music to accompany the commercial or use a preexisting song and edit it to match the flow of the commercial. Students would then need to answer what purpose the music serves in the commercial, how they utilized advertising principles, and how the metadimensions of the music enhanced the commercial.

Vivian Ellsworth: How We Experience, Understand, and Express Conflict; the Story of Romeo and Juliet in Music, Literature, Theatre, and Dance

To begin this set of lessons, note that students should have experience with form, texture charts, icons (graphic representations of music), mapping, Noteflight (http://www.noteflight.com), and GarageBand and be able to create schema maps and/or lists of musical dimensions. It will be necessary to ask a lot of questions to involve and support students in making the connections across the arts for intentionally scaffolded meaning making.

Students will be assessed in three main areas during this unit:

- Discussion participation. Students will ask questions and/or make comments verbally or in writing. As part of our discussion, we will be making a list (or schema map) of ways that writers, musicians, and choreographers create music to express conflict (through words, text, rhythm, timbre, instrumentation, motives, lighting, dynamics, repetition, etc.).

- Understanding of musical examples. Students will demonstrate this by completing the following:

- Create a map of Prokofiev’s “Montagues and Capulets.”

- Create an iconic representation of a repeated rhythmic or melodic motive from Bernstein’s “Mambo.”

- Create a texture chart for a movement from Nino Rota’s Romeo and Juliet soundtrack.

- Create a form chart for Michael Jackson’s “Beat It.”

- Creation of a soundtrack. With a partner, using Noteflight or GarageBand, students will make a one-minute segment of one of the following:

- fight scene in Zefferelli’s Romeo and Juliet

- Dance of the Montagues and Capulets (Prokofiev—ballet)

- rumble or dance from West Side Story

- Michael Jackson’s “Beat It”

The goal and objective of the first lesson is to get the students thinking about and listening for the ways authors, composers, and artists show conflict. Before we listen to or discuss any of the music, we look at specific lines from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and talk about Shakespeare himself. Examples can include act one, scene one to think about the foreshadowing that occurs there and act three, scene one for the rising tension of the fight. We will then do the following:

- Watch the ballet clip of a dance where the feuding families, the Montagues and the Capulets, are gathered. Do you feel conflict in this music? Do you see conflict or tension? How are the dancers moving? Can you tell from the dance how they feel about the other people in the room? What specifically does Prokofiev do in the music to show conflict?[13]

- Watch the following clip[14] of an orchestra playing the music from “Montagues and Capulets.” As you watch the orchestra playing, what do you feel? Have you ever seen an orchestra perform in person? Would it be different than watching a ballet and hearing the same music? What are you feeling as you listen to this music? What is Prokofiev doing to make you feel that way?

- Listen to an orchestral version several times to add further musical ideas to the incomplete musical map (with partners). The map shows the main violin line, yet there are many layers that students can explore (see Figure 4).

The next lesson focuses on the Zefferelli fight scenes. Play a fencing scene with and without music. Working independently, students will analyze the “background music” during the fight scene with a texture chart by drawing in other musical layers. The follow-up discussion will be scaffolded by the work on the texture charts. The teacher might ask how the music adds to the tension of the fight scene or instruct students to describe the texture. Students can also investigate which instruments are used to create the mood of conflict.[15]

Other musical problem solving activities include creating an iconic representation of a melodic or rhythmic motive that students hear in one of the movements and/or form and texture charts for other movements. The teacher can ask the following questions: Do you hear anything repeated in this music? Does seeing the graphic map help you to identify where it repeats? Do the same instruments always play the motive you chose?

Select movements with clear themes, as this is a time-intensive project that requires critical and creative thinking. The mambo (dance at the gym) from West Side Story would also provide context for discussing improvisation and the inherently competitive tension.[16]

In a final lesson, we explore Michael Jackson’s music video[17] for “Beat It” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ym0hZG-zNOk) to analyze the form of this song and complete the “What Do You Hear?” section of the form chart (see Figure 5). Additional questions might include the following: What is the role of the electric guitar in this piece? Where do you hear it? Is it the same each time you hear it? The guitar in the introduction is foreshadowing the fight, like Shakespeare does in his play.

Teachers might ask students to consider these questions: What will help you create music in your scene? What have other composers done that you can do? Will you use a rhythmic or melodic motive? Will you repeat segments of your music? Which beat patterns will you use? Which instruments will you use? Will you use acoustic or electronic instruments? A sharing of compositions will take place, with students describing their musical choices.

This unit provides a wide array of opportunities for musical thinking and doing across the arts that focus on essential questions (Brooks, 2002) and foster musical meaning making and personal expression.

Closing Thoughts

The aim of this chapter was to provide curricular examples that can offer teachers and teacher educators suggestions using popular music, media, and digitally based projects in their classrooms. This chapter provides an overview of a course that I teach with these goals in mind and includes examples designed by preservice music teachers that give a window into their vision of what might be possible for their future students.

With an intentionally constructivist approach to learning and teaching, these examples include aspects of learner choice, problem solving and posing, multiple perspective and multiple entry points, and connections across the arts. There is a focus on big ideas and essential questions with opportunities for creative and collaborative thinking and doing. As noted earlier, constructivism is not a method or a set of sequential steps to follow; these examples are provided as a framework that can be adjusted for one’s own students and classroom. Constructivist pedagogy requires a shift of attention from what to whom: “To understand constructivism, educators must focus attention on the learner . . . In order to realize the possibilities for learning that a constructivist pedagogy offers, schools need to take a closer, more respectful look at their learners” (Brooks & Brooks, 1993/1999, p. 22). Brooks and Brooks also state that

educational settings that encourage active construction of meaning have several characteristics:

- They free students from the dreariness of fact-driven curriculums and allow them to focus on large ideas.

- They place in students’ hands the exhilarating power to follow trails of interest, to make connections, to reformulate ideas, and to reach unique conclusions.

- They share with the students the important message that the world is a complex place in which multiple perspectives exist and truth is often a matter of interpretation. (pp. 21–22)

A big-picture outcome for educators is that designing student-centered musical experiences can cultivate learner agency. Bruner (1996) defined agency as “taking more control of your own mental activity” (p. 87) and noted that “the agentive view takes mind to be proactive, problem-oriented, attentionally focused, selective, constructional, directed to ends” (p. 93). The ability and opportunity to make musical decisions, use creative strategies in collaborative settings, and create frames (here, digitally and in popular music contexts) that foster understanding are key components of an agentive approach. But beyond the recognition of experiential activity, “what characterizes human selfhood is the construction of a conceptual system that organizes . . . as ‘record’ of agentive encounters with the world, a record that is related to the past . . . but that is also extrapolated into the future-self with history and with possibility” (p. 36). Teachers and learners will continue to interact in communities of learning—with a sense of history in the study of exemplars and with possibility as they envision and enact new forms of musical expression.

Notes

1. Citations in this chapter are intentionally drawn from readings used in our methods courses.

2. See http://www.littlekidsrock.org/.

3. For more information on flipped classrooms, see https://www.knewton.com/infographics/flipped-classroom/, http://www.thedailyriff.com/articles/how-the-flipped-classroom-is-radically-transforming-learning-536.php, and http://www.edutopia.org/blog/flipped-classroom-best-practices-andrew-miller.

4. In a flipped lesson, the teacher-provided information takes place at home (e.g., via video presentation or narrated PowerPoint), and the activity that would traditionally be considered homework is practiced or completed collaboratively in class.

5. Another interesting approach is to explore artists that have longevity in popular music with questions about cultural, historical, and musical trends that have shaped their musical journeys. Simon and Garfunkel’s own versions of Hazy Shade of Winter from 1967 and 2003 provide a starting point for this discussion, while Paul Simon’s Wristband (2016) offers a more current example.

6. These musical dimension diagrams are used with the permission of Wiggins (2015).

7. See example online at https://youtu.be/CypybdclX4k.

8. See example online at https://youtu.be/4nhhVIuX7rs.

9. WI Orchestra, https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/wi-orchestra/id434371426?mt=8.

Progression, https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/progression/id424281020?mt=8.

Chordica, https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/chordica/id302869050?mt=8.

10. This is an example of what that could look like: https://youtu.be/Qcr5j94PlLM.

11. This is a recording that I created as an example: https://youtu.be/pDHi8tDbysI.

12. Halla notes that these ideas were drawn from Huron (1989, pp. 557–574).

13. See Prokofiev, “Montagues and Capulets,” from Romeo and Juliet suite, Ballet Corella, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bI9akyHz_wc&feature=related.

14. See Prokofiev, suite no. 2, Romeo and Juliet, “Montagues and Capulets,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1_JUTAO0SA&list=RDp1_JUTAO0SA#t=37.

15. See act three, scene one, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ADvHO-lGjOs.

16. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kokbJvSEMUY.

17. See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H6Q8Lec1Wjg.

References

- Allsup, R. E. (2011). Popular music and classical musicians: Strategies and perspectives. Music Educators Journal, 97(3), 30–34.

- Barrett, J. R. (2001). Interdisciplinary work and musical integrity. Music Educators Journal, 87(5), 27–31.

- Blair, D. (March 2009). Stepping aside: Teaching in a student-centered music classroom. Music Educators Journal, 95(3), 42–45.

- Brooks, J. G. (2002). Schooling for life: Reclaiming the essence of learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

- Brooks, J. G., & Brooks, M. G. (1993/1999). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Davis, S. G. (2005). “That thing you do!” Compositional processes of a rock band. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 6(16). http://ijea/asu.edu/v6n16/.

- Davis, S. G. (2011). Fostering a “musical say”: Identity, expression and decision-making in a US school ensemble. In L. Green (Ed.), Learning, teaching and musical identity: Voices from across cultures (267–280). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: McMillan.

- Fosnot, C. T. (Ed.). (2005). Theory, perspectives, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Green, L. (2005). The music curriculum as lived experience: Children’s “natural” music-learning processes. Music Educators Journal, 91(4), 27–32.

- Huron, D. (1989). Music in advertising: An analytic paradigm. Musical Quarterly, 73(4), 557–574.

- Reimer, B. (2003). A philosophy of music education: Advancing the vision (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Ruthmann, A. (2007, March). The composers’ workshop: An approach to composing in the classroom. Music Educators Journal, 93(4), 38–43.

- Smidt, S. (2009). Introducing Vygotsky: A guide for practitioners and students in early years education. New York: Routledge.

- VanderLinde, D. (2014). “Mas que Nada”: Fostering musical understanding through listening, performing, and creating in popular music contexts (Workshop). ISME World Conference, Porto Alegre, Brazil, July 20–25.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Wiggins, J. (2015). Teaching for musical understanding (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wiggins, J. (2016). Musical agency. In G. McPherson (Ed.), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development (2nd ed., 102–121). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wiggins, R. (2001, March). Interdisciplinary curriculum: Music educator concerns. Music Educators Journal, 87(5), 40–44.

- Williams, D. A. (2014). Another perspective: The iPad is a REAL musical instrument. Music Educators Journal, 101(1), 93–98.

- Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17(2), 89–100.

- Zemelman, S., Daniels, H., & Hyde, A. (2005). Best practice: Today’s standards for teaching and learning in America’s schools (3rd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Appendix A: Materials For Alexander Walker Lessons

“We Shall Overcome”

Historical Period: Postwar United States, 1945–68

It was the most powerful song of the twentieth century. It started out in church pews and picket lines, inspired one of the greatest freedom movements in US history, and went on to topple governments and bring about reform all over the world. Word for word, the short, simple lyrics of “We Shall Overcome” might be some of the most influential words in the English language.

“We Shall Overcome” has its roots in African American hymns from the early twentieth century and was first used as a protest song in 1945, when striking tobacco workers in Charleston, South Carolina, sang it on their picket line. By the 1950s, the song had been discovered by the young activists of the civil rights movement, and it quickly became the movement’s unofficial anthem. Its verses were sung on protest marches and in sit-ins, through clouds of tear gas and under rows of police batons, and it brought courage and comfort to bruised, frightened activists as they waited in jail cells, wondering if they would survive the night. When the long years of struggle ended and President Lyndon B. Johnson vowed to fight for voting rights for all Americans, he included a final promise: “We shall overcome.”

In the decades since, the song has circled the globe and has been embraced by civil rights and prodemocracy movements in dozens of nations. From Northern Ireland to Eastern Europe, from Berlin to Beijing, and from South Africa to South America, its message of solidarity and hope has been sung in dozens of languages, in presidential palaces and in dark prisons, and it continues to lend its strength to all people struggling to be free.

As you listen to “We Shall Overcome,” think about the reasons it has brought strength and support to so many people for so many years. And remember that someone, somewhere, is singing it right now.

Citation

- “We Shall Overcome.” Library of Congress for Teachers. Library of Congress, n.d., June 2015. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/songs/overcome.html.

“Americano” by Lady Gaga: Workalong

- Listen to the song one time through and jot down five or six of the most salient musical features you hear. These can be instruments/timbres, lyrics, formal/structural elements, and so on.

- On the back of this page, construct a form diagram for this song. On the top of each section of the form, give the section a name. Underneath each section of the form, write as many unique musical or lyrical characteristics as you hear.

- Go pick up a copy of the lyrics and listen to the song again while reading along.

- Are there words or phrases you don’t understand? Look them up or translate them, and write the translation on the lyrics. (Staple the lyrics to this page and turn it in to me.)

- This song came out in 2011. What do you think the main social theme of this song is? Below, reference at least two supporting examples from the lyrics (you can use line numbers).

- Go to Wikipedia and type in “Americano (song).” Read the section titled “Background.”

- Did this illuminate yet another social issue explored in the song? What is it, and how was it weaved into this composition? (Hint: Think choices about musical instruments, or look at the “Credits & Personnel” section of the Wiki page.)

Pay close attention to producer Fernando Garibay’s remarks about when the song was written. Can you find a reference to this in the lyrics?

Appendix B: Resources For H. Hilborn “Music In Advertising” Unit

- http://www.marketingcharts.com/television/the-average-american-is-exposed-to-more-than-1-hour-of-tv-ads-every-day-42660/

- http://www.businessinsider.com/ace-metrix-most-well-liked-ads-of-2016-2016-4/#2-mms-zedd-and-blacc-likeability-score-756-attention-score-760-9

- http://www.businessinsider.com/ace-metrix-most-well-liked-ads-of-2016-2016-4/#2-mms-zedd-and-blacc-likeability-score-756-attention-score-760-9

- http://superbowlcommercials.tv/33442.html

- http://www.superbowlcommercials2016.org/best-commercials/best-2016-super-bowl-commercials/

- http://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/tv-and-culture/10-catchiest-commercial-jingles1.htm

- http://www.creativebloq.com/3d/top-tv-commercials-12121024/2