Screening Films for Full Houses: The 2020 True/False Festival Finds an Enthusiastic Audience

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The 17th annual True/False Film Fest opened on Thursday, March 5, 2020.[1] South by Southwest’s last minute decision to cancel its annual festival owing to the spread of the corona virus was made public one day later. Even if True/False had hoped to follow Austin’s lead, the decision came too late; True/ False had already begun. Over the course of the weekend, the pandemic, which had, until then, been buried on the back pages, started to make headlines. Epidemiological information was changing by the hour, and transmission became a growing concern: Had any attendees brought the virus to town without knowing it? Sitting next to someone who happened to be coughing became an increasing source of anxiety over the small span of time that separated Thursday’s premieres from the Fest’s closing film on Sunday. On the news networks, scientists were just starting to insist on the importance of separating fiction and non-fiction, and on the need to ground public health decisions in reality. At that point few of us knew just how strongly reality was going to bite America back in the weeks to come.

But the city of Columbia supports non-fiction filmmaking, and it really loves True/ False, so local enthusiasm for the Fest was largely unabated. This year’s program featured over 40 feature length films, about 20 art installations and dozens of musical performers. Regular attendees were monitoring every aspect of the Fest – its curation, its oversight, and the overall mood – especially keenly because of the recent shift in leadership. True/False’s founders, Paul Sturtz and David Wilson, who had been a constant presence in previous years, were no longer the event’s most visible faces. Both of them chose to step back from their duties, ceding responsibilities to new leadership. Festival veterans watched for changes, and insiders likely took note of differences, but from a casual attendee’s perspective little had changed. This was, once again, a well-managed festival with a solid lineup of films.

Because True/False places its highest premium on documentary film as art and tends to prioritize work by filmmakers with unique visions, the Fest’s curation has been consistently unlike other festivals. Although there are no specific selection criteria, True/ False prefers to include documentaries that provoke or challenge audiences, rather than ones that just deliver important information. Seeming topical or relevant does not guarantee a film a place on the program. If one looks back only over the last five years, the Fest’s line-up has consistently presaged the Academy’s choices, and the slates have included nominees such as Cartel Land (2015), I am Not your Negro (2016), Life, Animated (2016), Abacus: Small Enough to Jail (2016), Strong Island (2017), Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018), Of Fathers and Sons (2017), and The Edge of Democracy (2019), as well as last year’s Academy Award winner American Factory (2019). This year, films that audiences are likely to see in wider distribution include soon-to-be major releases such as Alexander Nanau’s chilling exposé of Romanian corruption Collective (2019), Kirsten Johnson’s deeply personal and funny Dick Johnson is Dead (2020), the highly entertaining Boys State (2020) from co-directors Jesse Moss and Amanda McBaine, and Garrett Bradley’s Time (2020), a story of one family’s experience with the US prison system, which recently sold to Amazon Studios.[2] In many cases these visible and well-regarded films arrived in mid-Missouri accompanied by their directors. While the Fest reliably includes no shortage of high-profile documentaries, many of the other excellent, groundbreaking and provocative films that screened there over that same five-year period might never find an audience elsewhere. Some of the most well received films from past Fests have long since disappeared from the public’s radar, without traceable afterlives. As an opportunity to see the biggest documentaries before they get to the public and to see some of the smallest ones that will vanish from view, the Fest continuously presents its attendees with a surfeit of singular opportunities.

Those who arrive in mid-Missouri and underestimate the ability of local viewers to assess, analyze, and critically engage with contemporary documentaries have their notions upended. Audiences were eager to see the premieres of films such as David Osit’s Mayor (2020), which deals with the tribulations of Musa Hadid, the mayor of Ramallah, whose daily tasks are constrained by the Israeli occupation, as well as David France’s Welcome to Chechnya (2020), which documents the extreme violence perpetrated against LGBTQ+ persons in Chechnya. These films screened for full houses in mid-Missouri, and the perceptible enthusiasm for such works would surely topple first-time visitors’ preconceptions.

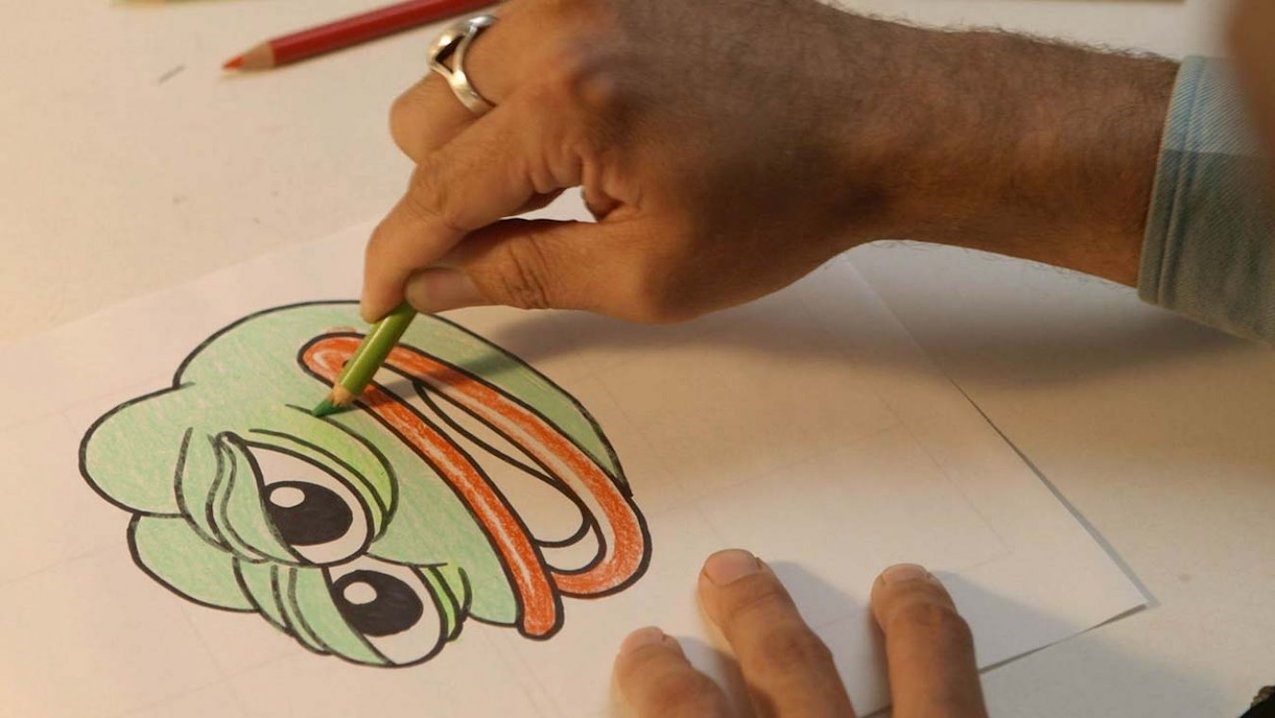

One of the first highlights of this year’s Fest was Arthur Jones’s Feels Good Man (2020), which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and won Sundance’s Special Jury Award for an Emerging Filmmaker. The film’s main subject, the artist Matt Furie who used to work at a thrift store in Kansas City, was responsible for the independently published comic Boy’s Club, which featured the character Pepe the Frog. Pepe’s image eventually became inseparably associated with the alt-right owing to its popularity on sites such as 4chan. A turning point for Furie came in May 2014 after the perpetrator of a violent shooting spree adopted Furie’s frog as an emblem for his struggle. The so-called “Pepe Trump meme” (aka “Smug Pepe”) subsequently became an electoral force in 2016. Furie, himself a subdued personality who by no means traffics in alt-right ideologies, finally felt as though he had no choice but to litigate for infringement when an Islamophobic children’s book appeared for sale on Amazon and featured characters based on his work. Jones’s documentary can be described as “Furie’s eventual reckoning with the bastardization of his brainchild.”[3] The film’s director moves seamlessly back and forth between documentary modes, featuring talking head interviews with social media experts such as Susan Blackmore, author of The Meme Machine (2000), and compelling cartoon animations that are both childlike and psychedelic. The film is not only a valuable portrait of an artist whose work was instrumentalized by forces beyond his control, but also for its depiction of a side of the independent comics culture that people do not generally see on film. Jones manages to condense a great deal of political information in short spaces and even leaves room for an optimistic ending that highlights the proliferation of Pepe memes in Hong Kong, where the frog image suddenly took on new life as a symbol of hope – for that city’s struggle to retain a liberal democracy in the fight against authoritarianism.

A film that will fly beneath most industry radars was Catskin (2020), which, although it is a Belgian film by a German-Filipino filmmaker, bears the German title Alle Sorten Rauh. That German-language title is intended to resonate with Allerlei Rauh, the title of a Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale sometimes translated as “All-Kinds-of-Fur.” The director, Ina Luchsperger, preferred not to have Anglophone viewers mistakenly treat the documentary as a fairy tale adaptation, so she titled it Catskin. Neither the English nor the German title convey the film’s concept: it centers on the ideological maturation of a 13-year-old Bavarian boy named Ludwig, who lives with his father Günter, and his grandmother (who is the filmmaker’s father’s first wife). When we first see Ludwig he is absorbed with his iPad, an anti-social habit that here portends further dissociative behavior. The true hazard, however, is the amount of time that he spends with Günter, who clearly loves his son but is beginning to sink deeper and deeper into the rhetoric of the German right with its xenophobic attitudes. Günter laments that the German government has taken distance from Germanic culture, away from true Volksempfinden, or a “healthy feeling for the national population,” which is a populist concept connected to the Third Reich. Günter repeats no shortage of recent bromides about how the government, in banning alt-right speech, is in fact the latest manifestation of authoritarianism. He echoes opinions similar to those that adherents of polemical right wing radio programs would hear in the US. For his part, Ludwig experiments with imitating his father’s transgressions: instead of a snowman, he builds a snow-Hitler, complete with mustache and salute. As a teenager, Ludwig stands on an ideological precipice and could apparently go either way.

The film moves subtly through the seasons, from winter to summer to winter again. As film critic Vadim Rizov notes, “There is a certain amount of value, or at least grueling resonance, in seeing a family get infected and rot in real time.”[4] Throughout the film Günter waxes openly about how a populace – a Volk –needs to have its identity; without an identity, Germany will be dominated, he says. Ludwig’s grandmother is aware of the dangers this rhetoric poses, but she rationalizes all of it as a function of her son’s loneliness and consoles herself with the company of her cats, with whom she engages in long theological discussions. The key question for Ludwig’s grandmother – and probably for the director of Catskin as well – is what will become of Ludwig, whose ideological health is nothing short of precarious: will he slide into xenophobia? The film never clearly mentions the Alternative for Germany party (the AfD), Germany’s major alt-right organization, which has become the expressive channel of choice for alienated men such as Günter. Comparisons with ideological conditions in the US – or with many western democracies at the moment – will abound in viewers’ minds.

One of the more languorous festival entries was The Faculties (Las facultades, 2019) by Argentine filmmaker Eloisa Soláas. The film is largely observational and bears comparison with Frederick Wiseman’s epic At Berkeley (2013), which depicted daily life at that university, both inside and outside the classroom. With its focus on exams, however, Soláas’s film might be still more comparable to Claire Simon’s The Competition (Le concours, 2016), a documentary centered solely on the entrance exam for la Fémis, the Parisian cinema school. Nearly all of the exams that are shown in Soláas’s film were held at the University of Buenos Aires, and the subject of this film is really the tradition of the oral exam as an element of public education. Soláas is studying how we perform our expertise; how doctors perform medicine and lawyers perform law. She seems to be suggesting that the oral exam is the first part of that project, the launching pad. We see, among the many oral examinations in the film, a professor questioning a student about the film theorist André Bazin and, eventually, asking for details about Battleship Potemkin (1925), which may give viewers who can follow the argument pause to reflect on documentary form and on what constitutes cinematic realism. Many other exams are depicted here: a physiology student studies pathways to the brain and whether patterns seem to emerge; another one takes a piano exam and his music constitutes the film’s occasional soundtrack; and yet another one studies the penal system. That last student seems to have been a prisoner himself, although one of the problems with this film is that the student’s backstory, among so many others, is left all too hazy.

The highest profile film on the program was most likely Boys State by Jesse Moss and Amanda McBaine. Boys State landed the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, and when A24 and Apple purchased it for 12 million dollars it broke the record for the highest acquisition price ever paid for a documentary.[5] The film played to a roaring full house at the 1,200-seat Missouri Theater, and many audience members remembered having seen Moss’s The Overnighters (2014) in that very same venue. Moss and the film’s editor said that the True/False screening was what they envisioned when they were completing their final edit. The film depicts the 2018 summer session of Boys State, a camp for more than 1,000 17-year-old politically precocious high school students who have been tasked with staging an intramural election campaign and a mock congressional session in order to learn about how the two-party system of government works. The film follows in particular a few well-chosen and charismatic protagonists, including Ben and René, who are elected as their respective parties’ chairs, and Steven and Rob, who become the competing gubernatorial candidates. The documentary does not contain as many twists as Moss’s The Overnighters, but as a competition film – a documentary subgenre – it keeps you guessing, never once telegraphing its final outcome. In asking how far the candidates are willing to go in mobilizing social media against one another, the film is about how young, aspiring politicians, from the most cynical to the most idealistic, imitate existing ones. Moss and McBaine’s work is largely observational, and the fact that participants of this age do not acknowledge the camera is an amazing accomplishment.

In that film’s opening sequence the directors remind us that many with political ambitions – including Bill Clinton, Rush Limbaugh, Cory Booker, and Dick Cheney –each attended Boys State in their home states. The high school students featured in the film imitate what they hear on cable news shows, and presumably from their parents, as they offer talking points on the second amendment and reproductive rights. Their willingness to ape the national conversation can be depressing, but the film hits an optimistic note where it shows the aspiring politicians being supportive of the Black, Latino and differently-abled students in their cohort. The film would pair well with competition documentaries, such as Vanessa Roth’s extraordinary First Monday in October (2006), a school election documentary that, akin to Boys State, examined the extent to which high school politicians imitated adult role models. It would also play well alongside The Revisionaries (2012), a truly grim portrait of the Texas School Board’s efforts to revise history textbooks in line with reactionary messaging.

One of the Fest’s most timely and challenging films was Down a Dark Stairwell (2020), a film about the 2014 police-involved shooting of Akai Gurley, an unarmed 28-year-old Black man. Most of the film takes place in Brooklyn, starting with the source of the 911 call from the Brooklyn housing project with which the film opens. On that call, we hear the witness say, “The cop shot him,” and the shooter turns out to be Chinese-American NYPD officer Peter Liang. The film then takes us to Chinatown where we hear about how Liang was more or less abandoned by the police department during the litigation. The director, Ursula Liang (who is not related to the shooter), takes her camera into the aggrieved Black communities and those of Chinese Americans who felt the officer had been treated unfairly. All involved come across as reasonable people pitted against one another by circumstances. Throughout the film, the director takes an even-handed and respectful approach, and most viewers would be hard pressed to guess whether she positions herself on one or another side of the conflict. Liang was found guilty on two counts, which was remarkable insofar as finding a police officer culpable in the shooting of a civilian was unprecedented. Ultimately, however, Liang’s lenient sentencing further exasperated the Black community. Despite the many interviews the filmmaker captured on camera, she keeps herself – both her physical presence and the extent of her sympathies – admirably outside of the frame. Down a Dark Stairwell, which grows more relevant by the day, is slated to play as part of PBS’s Independent Lens series and should not be missed.

Beyond Catskin, the Fest included a second fascinating documentary from Germany: Elke Margarete Lehrenkrauss’s Lovemobil (2019). Lehrenkrauss’s documentary focuses on the lives of two migrant sex workers, Milena and Rita, who live and work in Germany’s northwest region of Lower Saxony. Milena is from Bulgaria and Rita is from Nigeria. Lehrenkrauss spent over a year keeping company with them, and she also grants screen time to Uschi, an older woman who acts as somewhat of a pimp insofar as she owns the RVs out of which Milena and Rita work. We learn about Uschi’s own history of sex work from photos. When it comes to the women she oversees, Uschi has an unusual sense of propriety: she reprimands Rita for hanging her laundry out to dry, which makes for an odd metaphor given that she is a participant in a dirty-laundry-airing documentary about her employment of sex workers. We watch Milena and Rita endure no small amount of abuse from their customers, who are not the least bit reluctant to ask the women to do degrading things. However, very little sexual congress is depicted in the film; the filmmakers presumably did not want to be making pornography, but rather documenting the other forms of pressures – primarily personal, legal, and financial – to which the women are subjected. One of the film’s more excruciating sequences comes when Rita decides to work at the local strip club and see whether she can earn money there, but her potential employers are either too racist, or they believe that their clientele will be, and they decide not to hire her. According to the director, anti-immigrant legislation in 2015 resulted in Rita’s eventual return to Nigeria.

Still another of the Fest’s highlights – and one that will surely see wide distribution – was Kirsten Johnson’s Dick Johnson is Dead. Johnson, whose autobiographical and award-winning 2016 film Cameraperson also played at True/False, is primarily known as an accomplished documentary cinematographer. Her film, a darkly comic and performative reflection on her aging father’s mortality, is framed by her voice-over reflections on what it would mean for her to lose her father. The film’s set-up, which would be of interest to any psychologist, is that she is, through her filmmaking, trying to subject herself to the loss of her father before it actually happens. She thus stages several deaths for him, including one in which he is flattened by a falling air conditioner. She hires a stuntman to stand in and “die” for Dick Johnson, and she goes so far as to position her father in a coffin to see how he will look. All of this amounts to fun and games, but her father is actually losing his faculties and it is clear that the man she and her brother know and love is quickly fading away from them, regardless of whether he continues to live for some time. This serious point does not stop her from finding comedy in the situation – and her father, one should add, is an extraordinarily game participant. Among the funnier set pieces: she depicts Dick Johnson ascending to heaven, where his youth is restored and he can dance with his dead wife. For those interested in Johnson’s technique, it is worth noting how self-conscious she is about the camera, never hesitating to let it assume unlikely angles; she frequently reminds us that we are seeing through her lens, which is an approach appropriate to her personal style of filmmaking, and, as is evident in her groundbreaking Cameraperson, a camera, in her hands, can always be manipulated, adjusted, and refocused. In the Q&A Johnson referred to her film as “a different way to engage with death,” and she expressed the hope that it might inspire others to do the same.

Iranian filmmaker Mehrdad Oskouei returned to True/ False with Sunless Shadows (2019), a film that depicts imprisoned young women, between 15 and 17 years old, whose convictions each involve murders. All of the crimes for which the women have been sentenced are connected with domestic abuse; they fought back against raging fathers who beat their wives and daughters. The teenage women speak about their crimes directly into the camera, sometimes communicating with their similarly imprisoned mothers and sometimes with the deceased murder victims, conveying their regret. The film is a largely observational film, but the women in it occasionally speak to a private camera about what they have done, and, now and again, they address the filmmaker. Much of the film is focused on how they fill the hours while incarcerated; they pray, play hopscotch, and feed ducklings. Each of these moments reminds viewers that the women have yet to reach adulthood. Their mothers have different, harsher sentences: they are generally sentenced to death, although those executions are – at least on the basis of what we see in this film – not always carried out. This film is of a piece with Oskouei’s Starless Dreams (2016), which was about young teenage girls in a rehabilitation and correction center on the outskirts of Tehran. The film played at True/False four years ago when he was the Fest’s True Vision award winner.[6] The efforts at rehabilitation, as they are depicted in these films, look quite humane, even if the circumstances that put the women there – an epidemic of domestic abuse – are widespread. The conditions in which the young women are imprisoned appear civilized, but the conditions that led them into murderous circumstances surely persist.

My favorite film at this year’s Fest was Mayor. David Osit, the film’s director, premiered Building Babel (2011), his first documentary, at True/ False in 2012. That film documented Sharif el-Gamal’s struggle to build an Islamic cultural center two blocks from where the World Trade Center towers once stood. A few years later, when Osit heard about Hadid Musa, the mayor of Ramallah, he became curious and began an observational project that yielded about 350 hours of footage. A Star Wars-style crawl at the film’s beginning provides audiences outside the Middle East some necessary background information about Ramallah. Mayor Musa is charming and is delightfully obtuse about concepts such as city “branding.” While Osit was filming, the Trump administration announced that it would be moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and the inflammatory decision sparked protests across the country including in Ramallah. When the Mayor’s office first hears that the move has been authorized (“we’re doomed,” says the mayor’s worried priest-advisor), the Mayor complains that he is always the last to know. We come to find out that he doesn’t have a radio or cable television in his office, to say nothing of his inability to use Facebook Live.

Throughout the film, Mayor Musa meets with dignitaries from other countries, most of whom want to plan cultural exchanges in the form of soccer games. The Mayor’s interest is in communicating the extent of their human rights violations. Although his job involves planning a tree-lighting celebration and fireworks, he is frustrated by not having say in decisions that affect his municipality, which would include control over the sewage pipes that flow in and out of the city. At some point in the director’s many hours observing the mayor, he witnessed and filmed Israeli military incursions into the city – soldiers came in heavily armed and were chased out by residents with rocks. Incidents of this sort get absorbed into the rhythms of daily life, and, afterward, he goes back to determining the size of volleyball courts. The film does an extraordinary job of putting us in Mayor Musa’s shoes: is he responsible for a municipality or for an occupied city compelled to endure human rights violations? In the Q&A, Osit pointed out that the film isn’t called “Mayor Musa,” but rather Mayor, implying that Osit is trying to contend not just with the Mayor’s decisions, but with the larger complications associated with the occupation, complications that any mayor who takes that job would face.

As ever, this year’s Fest featured an international line-up, and a flood of provocative and engrossing documentaries from Palestine, Iran, Israel, Germany, and elsewhere made their way to mid-Missouri. Starting this summer, leadership of True/ False is being handed over to Barbie Banks, Camellia Cosgray, and Arin Liberman, three women who have, over the years, played various roles in administrating the Fest, and the dates for next year (March 4-7, 2021) have been set.[7] As with many festivals around the world, it is not clear what the format will be. One may, however, assume that it will be as international, engaging, and thoughtful about involving its audience, regardless of how much of it is conducted virtually and how much is face-to-face, as it has been in the past. The 2020 Fest will certainly not have been True/ False’s last, not even for a while. The need for nonfiction is now greater than ever. One should no longer have to be reminded that reality – even if in the form of reality-based filmmaking – is paramount. We ignore it at our peril.

Author Biography

Brad Prager is Professor of Film Studies and German Studies at the University of Missouri. His areas of research include Holocaust Studies, Film History, and Contemporary German Cinema. He is the author of After the Fact: The Holocaust in Twenty-First Century Documentary Film (2015) and The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth (2007). His most recent book is a study of Christian Petzold's 2014 German film Phoenix, which was published last fall by Camden House.

Notes

The True/False organization prefers that the festival be referred to as a “fest” rather than as a “festival.” This festival report adheres to that convention.

True/ False does not screen films that are currently available on streaming platforms. However, they do not put as high a premium on premieres as many other festivals and are willing to program films that have played at Sundance or at IDFA.

Aarik Danielsen, “Former Missourian traces rise, fall of Pepe the Frog in True/False documentary,” Columbiatribune.com, March 3, 2020. https://www.columbiatribune.com/entertainment/20200303/former-missourian-traces-rise-fall-of-pepe-frog-in-truefalse-documentary

Vadim Rizov, “True/False Film Fest 2020: The Value of the Theatrical Experience (Coronavirus Remix),” Filmmakermagazine.com, March 25, 2020. https://filmmakermagazine.com/109321-true-false-film-fest-2020-the-value-of-the-theatrical-experience-coronavirus-remix/

“The previous record for the largest documentary sale at Sundance was 2019’s Knock Down the House, which sold for $10 million. Sources say Netflix and Hulu were also bidding at $12 million.” See Tatiana Siegel, “Sundance: Apple, A24 Nab Hot Doc Boys State for Record-Breaking $12M,” Hollywoodreporter.com, January 27, 2020, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/apple-a24-nab-hot-doc-boys-state-12m-sundance-1273684

The Fest does not hold a competition, and the True Vision Award is the only award given by True/ False. It is an annual honorary award given to a filmmaker who has advanced the art nonfiction filmmaking. The 2020 co-winners were Bill and Turner Ross, directors of directors of Western (2015) and Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (2020)

Anne Thompson, “True/False Film Fest Gains New Leadership as the Future Remains Uncertain — Exclusive,” indiewire.com, June 26, 2020, https://www.indiewire.com/2020/06/ragtag-true-false-film-fest-future-1234569847/