Multiplying Mise-en-Scène: Found Sounds of The Night of the Hunter in Lewis Klahr’s Daylight Moon and Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma[1]

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract:

This essay situates music as a crucial catalyst in a film’s mise-en-scène (the multisensory interface that pulls spectators into films’ worlds). Developing a contour theory of mise-en-scène inspired by Cahiers du Cinéma critic Michel Mourlet, I track how sonic textures, vibrations, and rhythms have similarly palpable effects to the oft-cited visual elements of lights, shadows, and actors’ gestures. Whereas standard analyses of leitmotifs match melodies with single icons, contours multiply figurative and emotional associations as spectators see and hear the seams between mise-en-scène elements. To demonstrate this approach, I closely analyze The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955) and two films that appropriate its audio-visual material: Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998) and Lewis Klahr’s Daylight Moon (2002). While the former narrative film could be read through leitmotifs, its non-diegetic sounds thwart straightforward correlations, like the experimental films’ found sounds. A contour theory multiplies mise-en-scène with audio-visual superimpositions.

Mise-en-scène studies have long discussed film worlds created on- and offscreen, characterized already by Hugo Münsterberg in the 1910s as an interplay between cinematic projections and those of viewers’ minds.[2] But mise-en-scène extends beyond visual elements of setting, lighting, and acting: tones of music and dialogue, for example, are crucial to convey how characters relate to one another and to their world. For John Gibbs and Douglas Pye, “tone, vocal inflection, gesture and posture” heighten the mise-en-scène’s “constantly shifting texture” as they intertwine with narratives on both surface and deeper levels. Recent attention to multisensory tones of meaning have redressed mise-en-scène theories in which sound is mere window dressing, an emotive offshoot of the continuity system.[3] This essay builds on such studies to posit sounds as textural and dimensional elements that shape space, time, and emotion. I argue that in creating audio-visual contours that spark spectators’ memories and associations, music and sound are bound up with and central to world-building in film. When music underscores conversations or sound effects foreshadow ominous developments beyond the frame, soundscapes construct worlds by amplifying the underlying relations between characters and environments. Film sound immerses spectators in an imaginary world but also influences their reactions to it, as aural cues of emotions and situations palpably extend the world visible in the frame.

While Gibbs and Pye and other theorists have included sound as an element of mise-en-scène, they have not fully reckoned with the challenges that non-diegetic sound, and especially music, pose for analyses of diegetic space. Many writers consider music/image relations only through leitmotif theories—which exemplify what I term correlation models—that map melodies onto certain characters and themes.[4] It’s a tendency that leads to critical shortcomings. While leitmotifs can recur in slight variations to show a character’s emotional development, subtle music/image juxtapositions defamiliarize the ways in which bodies and objects come to matter and mean. World-building becomes even more complex when music and non-diegetic sounds are imported from previous films. As spectators recognize pre-existing sounds, one-to-one correlations of melodies and symbols clash with visions of other diegetic spaces.[5] Correlation models (perhaps these could even be termed correlationist models) fail to register such collisions of world-building, but the contour model I propose is well-equipped to account for the multiple planes—both diegetic and non-diegetic—that music brings to images and imaginations.

To explain music’s world-building contours, I turn to a 1959 essay by Michel Mourlet to outline the contour theory of mise-en-scène. In an essay that remains largely unknown to Anglophone scholars, Mourlet proposes mise-en-scène as a phenomenological experience of graphic contours, in which visual motifs of lighting, actors’ gestures, and camera movements create patterns that trace characters’ moods and developments.[6] In this essay, I adapt Mourlet’s theory to show how film sound, music, and voice expand dimensions of filmic worlds. A multisensory approach to sounds’ affective, thematic, and narrative contours situates them as central components of mise-en-scène. Melodic contours do not just mimic or metaphorize human emotions or operate in separate channels from the “visual” mise-en-scène.[7] They are sonic extensions of what Germaine Dulac described as the visual symphony of cinema, where the graphic dimensions of sets, lighting, and shadows compose “a rhythm of arranged movements in which the shifting of a line, or of a volume in a changing cadence creates emotion without any crystallization of ideas.”[8] No longer separated from images as window dressing, sounds collide with objects to produce a matrix of textures that impact how we relate to filmic worlds. Audio-visual contours appeal to listeners’ embodied memories of sensory experiences: sight and sound become mediated by tactile recollections, akin to Laura Marks’s theory where cinematic close-ups “evoke touch and visceral memory [...] of fingers tightening around throats but also of the gut-felt feelings of violation.”[9] In such a way, sonic timbres and melodic lines accrue emotional residue through tone and texture to remind spectators of previous bodily encounters.

In what follows, I offer a model of thinking about mise-en-scène that incorporates sound and image, not as montage or leitmotivic but as immersive. Beyond correlation models, a contour approach provides fuller-bodied associations that bring aural—not just ocularcentric—worldviews to the forefront of attention. An aural worldview (a purposely playful oxymoron) multiplies a spectator’s capacity to sense the continuum—and contingency—between real and fantasy worlds. My case studies of both narrative and avant-garde films demonstrate this theory’s wide-ranging applications. In The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955) and its afterlives—Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998) and Lewis Klahr’s Daylight Moon (2002)—complex mise-en-scènes become ever more baroque as they recycle and remediate found sound. The later films’ use of found sounds especially allow spectators to sense when worldly materials collide: recurring contours amplify diegetic and non-diegetic musical contingencies.

Audio-Visual Contours in The Night of the Hunter

The Night of the Hunter, with its simultaneously real and nightmarish cinematography and leitmotifs, exemplifies how a contour theory of mise-en-scène improves upon correlation models to specify how films build worlds. To depict Preacher Powell’s attempts to steal the inheritance of orphans John and Pearl, Laughton mixes German expressionist “Caligarism” of black-and-white chiaroscuro light and shadow play with the realistic styles of D.W. Griffith, Orson Welles, and Biblical tales. This stylistic tension is found in the film’s opening shots, which start with a starry sky that introduces the floating face of Lilian Gish; as “Miz Cooper” warns her adopted orphans to beware of false prophets, the stylized celestial scene cuts to a bird’s eye view over a town. In a more realistic aesthetic, mobile camera shots oscillate from John and Pearl playing upriver to Preacher’s car snaking up a road, drawing contours at once consonant and dissonant between the protagonists. Even before these establishing shots, though, the credit music launches thematic tensions between good and evil. Composer Walter Schumann called the heavy four brass chords that often accompany Preacher a “‘pagan motif, consisting of clashing fifths in the lower register,’”[10] which cede to the lullaby “Dream, Little One, Dream” with a shot of Gish. This celestial lullaby foreshadows her adoption of the children after they escape downriver. In the opening and river sequences especially, audio-visions juxtapose fantasy and reality, and good and evil, to propel the children to safety.

In these sequences, Laughton’s visual constructions and Schumann’s score establish abstract contours that take root in spectatorial memory. When the overture transitions from Preacher’s pagan motif to a tranquil lullaby, celestial sounds and Gish’s presence seem to safeguard the children from Preacher’s tyranny. Yet, the bird’s eye view that introduces Preacher ironically elicits heavenly connotations. From the outset, the film blurs the lines between “moral” reality and “escapist” fantasy—two different models of building filmic worlds. Preacher exhibits this binary in his “story of right-hand/left-hand”: he has H-A-T-E written on his left-hand knuckles and L-O-V-E on his right. (Coincidentally, Laughton called Schumann his “right-hand” man.) As “the left hand,” Laughton asked cinematographer Stanley Cortez to shoot scenes well past their scripted length to allow Schumann to compose whichever music fit the scene emotionally, rather than the often reversed process.[11] The score buoys Laughton’s narrative and character development at the same time that it breathes fantasy into the mise-en-scène. But accounts of Hunter by Simon Callow and Jeffrey Couchman primarily analyze its music through leitmotifs, prioritizing literal correlations over emotive fantasy and diminishing their simultaneity.

From the beginning of their collaboration, Laughton and Schumann paid homage to the melodramatic elements of Davis Grubb’s novel with lyric photography and abstract music[12]—art forms that embody the etymology of melos (music) plus drama. Schumann’s pagan motif, Miz Cooper’s lullaby, and the sounds of the children’s river journey mix realistic tropes and emotional flourishes in the manner of 1950s melodrama films, which especially employed music to articulate these opposing poles. For Peter Brooks, music punctuates the wordless gestures of the melodramatic “text of muteness”: its sweeping rhythmic motions render space and time tangible to imbue characters—especially muted victims—with emotional depth.[13] Thomas Elsaesser further elaborates the role of music in melodrama as “noncommunication or silence made eloquent” that triggers “the recognition of different levels of awareness.”[14] Music, along with camera movement and lens depth, fills out multiple planes in an image, as leitmotivic cues both reach backward towards a spectator’s memory and forward towards their anticipation of a character’s fate.

Leitmotifs—recurring musical themes that refer to people, places, or emotions—often are attributed to Richard Wagner, whose Ring cycle operas codified characters and objects. From 18th-century theatre to silent film accompaniment, leitmotifs solidified into paraphrasable meanings of certain situations and emotions.[15] In the sound era, studio systems trained spectators to match musical themes with characters and psychological traits; repetitive leitmotifs rendered abstract music concrete to augment reality effects for audiences. Yet, leitmotifs can convey more than just tokens of realism: even in the mode of classical narrative, music also conjures up spectators’ embodied memories as they consider characters’ internal motivations. As Jean-Paul Sartre states in his memoir, his identification with silent film characters was deepened “by means of music; it was the sound of their inner life.”[16] Through the accompaniment that spoke for le cinéma muet, characters’ hardships “permeated” and “entered” Sartre’s body. For example, he remarks that “the young widow who wept on the screen was not I, and yet she and I had only one soul: Chopin’s funeral march; no more was needed for her tears to wet my eyes.”[17]

In such moments, we see how music choreographs shared experiences between spectators and characters, the real and the fantastic, and on- and off-screen audio-visual elements. Beyond merely signifying characters’ emotions as static leitmotifs, directors’ mise-en-scène constructions—such as close-ups timed with musical flourishes—impel audience members to feel as if they react from within affective situations. Both camera and musical movements position spectators alongside characters, no longer just viewers onto a world. For Sartre, the cultural codes of silent film music communicate actions in the plot but also become experiential contours in the mise-en-scène: the permeating force of sound triggers affective memory, simultaneously evoking real events and characters’ emotions. Aural contours both articulate and collapse the bounds between fantasy and real life: sounds evoke scenes from spectators’ aural memory banks, suffusing events onscreen with sensations from past ordeals.

Figure 2: A clip from the infamous river sequence in the middle of The Night of the Hunter.

An example of how music superimposes worlds to spark our cathartic recognition occurs in The Night of the Hunter’s river sequence, which mixes modes of real-world identification and surrealist dream as the children escape from Preacher. When the images become increasingly abstract—river creatures appear in larger-than-life forms—the music creates a vehicle for spectatorial identification with the children’s fear. Schumann interweaves motifs of the children’s flight and Preacher’s threat: the opening lullaby recurs at an increased tempo in the high strings while the low brass play Preacher’s ominous fanfare. As the children launch their skiff, Preacher emits a grotesque moan—amplified by sound designer Stanford Houghton in post-production—which contrasts sharply with subsequent celestial string tremolos. For Jeffrey Couchman, this suddenly placid music marks a transition from “otherworldly evil” to “otherworldly goodness.”[18] Yet this delineation is not as sharp as Couchman describes: Preacher’s scream erupts into a chorus of voices that sound human but clearly are manipulated electronically. The manufactured, eerie residue of his outburst hints that the children may not elude his grasp for long. Trailing its echoes, gentler choral voices spawn images of fantastic animals that loom large against the tiny children. Ironically, the “natural” human voice triggers a collapse between realism and abstraction, possibly dislodging spectators’ willing suspensions of disbelief. Thus, music acts as both affective glue to immerse spectators in a dreamland—a use of music common in narrative film—and as a projective force of memory simultaneously internal and external to the film. Especially in lullabies that encourage reverie, musical motifs unspool the memory reels of characters and spectators to prompt anticipation of the children’s deliverance from evil.

Two lullabies—one by Pearl and then an offscreen, maternal voice—depict figures that the children conjure to carry them to safety. After the children sail out of Preacher’s grasp, the next shot of a star-filled sky rhymes with the opening credit sequence. Glimmering stars soothe against the darkness of Preacher’s relentless pursuit but also recall Gish’s comforting voice to the children in the credits. Chimes and strings evoke her pacifying tone alongside teenager Betty Benson’s quavering soprano voice, which was dubbed in for Pearl (played by Sally Jane Bruce). Bruce lip syncs, “Once upon a time there was a pretty fly / he had a pretty wife [...] / But one day she flew away, flew away...”[19] The melody climbs higher on “flew away” to trace the countours of Grubb’s lyrics, which invoke the animal totem of a fly as Pearl imagines a terrain safe from Preacher.

Pearl’s lullaby accompanies images of creatures that help to establish the river as a tenuous refuge. Shots as languid as the river engage new perspectives: an extreme high angle through a spider web, as if from a spider’s point of view, cuts to a straight-on shot of the children from behind a large frog. The spider webs and observant animals contribute simultaneously to senses of safety and uncertainty. When Pearl’s voice trails off, the music and images dovetail in expectant contours. As the children’s skiff passes several different terrains, the forward-flowing music imbues the images with a quickened sense of time. Simultaneously, Schumann uses the oboe and English horn—instruments that evoke the pastoral given their roots in shepherds’ pipes[20]—to transport spectators to each new riverbank locale, increasing our spatial and emotional awareness of the children’s plight.

The onlooking animals and lullabies thus signal as at once earthly and heavenly, even maternal, guardians. Grubb hoped that Laughton’s audience would experience the river as “the womb of safety” through the film’s cinematography and score[21]—even though Preacher’s bestial howl still reverberates ominously. To confront this otherworldly force, the two lullabies voiced by Pearl and an older woman solicit on- and offscreen images from spectators’ memories. After Pearl’s lullaby, the children approach a farmhouse to the acousmatic, lush tones of jazz singer Kitty White reprising “Dream, Little One, Dream”: “Hush, little one, hush / Morning soon shall light your pillow, / Birds will sing in yonder willow.”[22] This last phrase prompts a cut-in to a window lit to reveal a birdcage and a curved shadow. As the song precedes the shot of the house, spectators are primed to code this shadowy presence and soothing timbres as maternal. Moreover, since “Dream” (sung by children) first accompanied Miz Cooper’s appearance in the opening credits, the acousmêtre foreshadows the children’s proximity to Miz Cooper’s final refuge. But this acousmatic safety dissipates when Preacher’s hymn “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” also resonates offscreen and his shadow looms near the children’s temporary shelter. While many timbral and melodic contours in the river sequence convey reassurance, non-diegetic music and otherworldly voices conjure multiple senses of shadows and safety to superimpose real and imagined threats in Hunter’s world.

Musical Models of Mise-en-Scène: Sensing Multilayered Worlds

The familiar way of analyzing the use of music in a narrative film like Hunter is through the logic of the leitmotif. This way of thinking would trace Schumann’s designated themes through visual correlations to show how they accrue associations over the course of the film. By contrast, I propose an alternate model, one inspired by the writings of mise-en-scène critics of the Cahiers du Cinéma group—and Michel Mourlet in particular. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Mourlet was well-known in France, and continues to be read there, but as with many critics his essays have yet to be translated into English. In a central 1959 essay, Mourlet analyzes how images, sounds, and technological effects fascinate and immerse spectators in the mise-en-scène.

Mourlet’s essay parallels Sartre’s phenomenological account of spectatorial absorption. Whereas Sartre identifies fantasmatically with characters through melodic contours that summon previous associations of movement and emotion, Mourlet notes visual arcs of camera movements, cuts, and actors’ gazes that “[r]ecreat[e] our anticipation in each instant anew, and the continual metamorphoses of the sensible world trace in space the lines of an unforeseen and ineluctable music.”[23] For Mourlet, filmic space and time absorb spectators “to varying degrees,” or physiological thresholds in which some are more attuned to vision, others to sound, and still others to texture. This variegated absorption arises from “the lines of an unforeseen and ineluctable music”—what I call graphic and musical contours that reveal slices of cinematic worlds. Blending realism and abstraction, contours provoke spectators to process phenomena both as they happen to characters and in relation to their memories and affiliations.

Mourlet’s fittingly musical language unfurls the concrete effects of subtle visual contours in the mise-en-scène. With vertiginous camera movements or shadows that pirouette between actors and settings, a director creates a “melodic line, with its crescendos, its pauses, its outbursts, the secret movements of being, piercing us to the marrow by ways of peril and exaltation.”[24] As directors introduce contours that are unfamiliar to a spectator’s habitual way of seeing, they use sweeping strains of music to create moments of self-dispossession in a diegesis. Like an intoxicating melody, mise-en-scène transports spectators to a new space and time that nonetheless feels uncannily intimate. Spectators temporarily become dissociated from their bodies to encounter a character’s “gestures, gazes, minute movements of the face and the body, [and] vocal inflections in which we lose ourselves before regaining possession of ourselves, expanded, lucid, and soothed.”[25] Thus, while embodied camera movements, well-lit close-ups from unexpected camera angles, or an actor’s tone of voice might at first startle spectators as new perspectives, our previous encounters reground them with shape and meaning. Like we rely on historical and artistic forms to categorize unfamiliar images, deciphering the ineluctable music of mise-en-scène also depends on memories and codifications of music. Far from a singular signifier, music proliferates a range of resonances akin to Eisenstein’s theory of overtonal montage, where dialectical chord-like compositions of lighting, gesture, and motion can produce “direct physiological sensation[s]” of overtones both visual and felt.[26] That is, when a musician plays or sings a note, it can set off vibrations that emit higher sonic frequencies—overtones. Such vibrations are not merely tuneful but also disturb the air with multisensory dissonance, a collision of musical and physiological material. Mise-en-scène elements that commingle in surprising contours trigger felt disturbances and embodied memories: overloud or edgy sounds that don’t quite match up with onscreen spaces or images summon a bodily experience of dissonance that at once reminds and recasts one’s everyday associations with sounds. This can be seen in the non-naturalistic mode of Hunter, where audio-visual dissonances occur even for listeners unfamiliar with classical music conventions as they detect the constructedness of Preacher’s cry or “Pearl’s” teenage voice. Contrary to their voice acting, Preacher doesn’t sound quite human, and Pearl seems to have morphed into a teenager. As spectators’ recollections of previously experienced sounds and images collide with fabricated scenes, mise-en-scène contours invite spectators to see, hear, and feel the seams between elements.

Instead of conventional leitmotif-driven criticism that attaches Schumann’s sinister motif only to Preacher, a contour theory of mise-en-scène that emerges from Mourlet opens up new pathways to and from the film’s world. Sound multiplies vision beyond a window onto a world: audio-visual contours loosen leitmotivs’ paraphrasable meanings as sonic overtones prompt spectators to react to situations within the film through their own associations. This structural model reframes sounds as real/imaginary superimpositions, not merely reality sound effects. Analyzed through a motivic model that binds characters to themes, Hunter’s river lullabies foreshadow the children’s eventual safety with Miz Cooper even though maternal figures are not visible. But motivic criticism misses the voice/body discrepancies between Pearl and her vocal double, and the otherworldly contours of Preacher’s bestial howl.

As I’ve tried to show, a contour model expands leitmotivic analyses of narrative films, especially when creative uses of sound escape the bonds of motivic correlations. But contours also, and importantly, help us to unpack the aural worldviews of experimental films that use sounds to make tactile appeals to audience memory. Trails of musical contours become especially important when such films appropriate images and sounds from other works and put them to other historical and ideological purposes. Spectators who track the edges of found materials grasp memories of their original contexts and notice their transformations. Contours make the collisions of non-diegetic sounds and diegetic scenes palpable: music superimposes spatial, temporal, and emotional elements of films to overlay aural worldviews.

Figure 5: Hunter reappears in Episode 2A of Histoire(s) du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard). Histoire(s) du cinéma

As a cult film beloved by cinephiles, Hunter’s afterlife is animated both by spectatorial memory and films that cite its audio-visual material. Found sounds unleash consonances and dissonances as spectators remember moments in Hunter but encounter audio-visual material with new narrative and emotional associations—as in the heavy-handed superimpositions of Jean-Luc Godard in Histoire(s) du cinéma. In Episode 2A, “Seul le cinéma,” Godard borrows shots from Hunter’s river sequence as he muses about cinema’s capacity for imaginative travel. His multisensory superimpositions convey affordances of cinematic technology. Webern’s String Quartet, Op. 28 (1936-8) launches the sequence “Envoi 1,” where a young Julie Delpy reads Baudelaire’s “Le Voyage.” Godard intercuts close-ups of the adolescent’s pristine eyes and mouth with Joseph Turner’s painting Peace: Burial at Sea (1842) and early shots from Hunter’s river sequence that especially highlight animals. Amid numerous inferential cuts and superimpositions, Godard imports Hunter’s images but omits Preacher’s scream and Schumann’s score. Without sound to accompany Preacher’s scream, Godard as the arbiter of cinematic mediation seems to position himself as the con man who hunts the threads of cinematic memory. In a similarly perverse move, he replaces the film’s subtle animal sounds with vehement croaks, birdcalls, and hoots that poke through Webern’s foreboding strains. Why would Godard return to Hunter’s child’s play but alter its soundtrack in this way? The answer would seem to lie in his fixation on Delpy’s eyes and mouth, showcasing a desire to fix interpenetrations of image and sound in direct correlations.

Godard’s complex audio-visual constructions evoke Hunter’s fascination with childhood, cultural history, and especially film history, but his aggressive montage stamps correspondences onto the surface of mise-en-scène that stifle some of Hunter’s imaginative play. Visually, Godard fetishizes John and Pearl’s fantastic encounters with animals to attend to the literal text of Baudelaire’s poem and its young reader’s introspective display of imaginative travel. Richard Neer’s recounting of literal and allusive correspondences in the montage of “Envoi 1” is instructive here. As Delpy’s lips shape the French strophes, Godard merges her facial profile with Turner’s ship: the curve of her lips matches the bow, and later her hair tangles with Laughton’s reeds.[27] Godard literalizes contours as exact correlations of motifs and meanings: dissolves and freeze frames cause the ship’s sails and John and Pearl to emerge from Delpy’s eyes and mouth. As visual play invokes the oral, Godard provokes sensory—and sensual—interrelations. For Baudelaire’s poem in the mouth of Delpy paints a nymphlike muse coming of age through the world of images:[28]

| Pour l’enfant, amoureux de cartes et d’estampes, | For the child, in love with maps and engravings, |

| L’univers est égal à son vaste appétit. | the universe is equal to his vast appetite. |

| Ah! que le monde est grand à la clarté des lampes! | Ah! How great the world is by lamplight! |

| Aux yeux du souvenir que le monde est petit! | In the eyes of memory, how the world is small! |

To Godard, Baudelaire’s 1861 poem presages ways that cinema will transform imagination, as exhibited by rampant superimpositions.[29] Godard affirms the integrative force of contour theory with ontologically separate sources of painting, film, video, and piped-in sounds—their formal affinities communicate a larger story about memory. But Histoire(s) seeks to fix memory rather than to free it: its superimposed contours memorialize twentieth-century cinema history.

Histoire(s) uses contours to reflect upon historical events in an authoritative register. To discuss how cinema brought a modern sensibility to the twentieth century, Godard imports distinct sources from the radical twelve-tone Webern quartet to Baudelaire, whom Benjamin described as an allegorist lifting fragments from perceived continuities to recast official historical narratives with new kinds of meaning.[30] If Hunter has its own explosion of fragments, fusing divergent silent cinema styles of Caligari’s expressionism and Griffith’s realism but in a way that allows spectators to trace their seams, then Histoire(s) compiles sources around Godard’s narrative voice (whether in textual, sonic, or visual superimposition) to pull spectators into a cinematic world preordained by his knotted correlations instead of individual memory.[31] Godard thus decontextualizes the valences of childhood given in Hunter and Baudelaire to weave an allegory of maturation that enlists Delpy as the mouthpiece of cinema’s pursuit of correspondences. Delpy’s maturation from girl to woman complements Godard’s interpretation of Baudelaire’s poem: her soft voice becomes more assured—and recalls the aging effects of Pearl’s vocal double—as images from Laughton’s expanded world proliferate in and around her. But Godard’s glaring fetishization of Delpy is not the only time audiences might recoil: her soft voice also is no match for the overly loud animal sounds that hearken the blunt reality of the coming-of-age scene. At their volume, they bombastically assert nature as, by Godard’s superimposed extension, the inevitability of mating calls intrude on a child’s dream. Sonic manipulation thus raises the bar of cultural imposition as Godard positions the animal sounds to speak the “truth” of Delpy’s sexualized body. His illustrative joke between eye and mouth posits sound synchronization as a kind of striptease, echoing Michel Chion’s declaration that “the spectator’s eye [... ‘verifies’ the] end point of de-acousmatization—the mouth from which the voice issues.”[32] As Godard pierces Delpy’s eyes and mouth with ships and aurally imposes fantasies of sexualized nature, he knowingly exposes the artifice of superimposition, but at the cost of reinstalling sound as the truth-teller between one’s interior and exterior natures.[33] In this way, Godard’s formal affinities veer close to leitmotivic criticism, creating iconic relations that consign contours to a correlation theory. Yet this leitmotivic structure, perhaps paradoxically, is only revealed by attending to a contour model.

New Aural Worldviews in Daylight Moon

Contours need not correspond—as seen in another The Night of the Hunter afterlife. Lewis Klahr’s avant-garde film Daylight Moon (2002), made with largely two-dimensional collage objects, rhymes somewhat with Godard’s visual abstractions (at times even conjuring 1920s pure cinema) but his use of Hunter’s music elicits individual, emotional resonances that Histoire(s) forecloses. Whereas Godard’s childlike sounds make claims to realism and “truths” of the female body, Klahr’s textured qualities of sounds invite grasps toward the instability and power of memory. Via attention to contours, spectators who hear Hunter again in Klahr’s film find multiple worlds at play, as found objects index pastness through melodic contours and record crackles. As with Histoire(s), a contour model readily extends to musical accompaniment that is imported as found sound—even to Klahr’s nearly free associations. The Los Angeles-based filmmaker has been fascinated from childhood with Hollywood cinema’s narratives and themes, which resurface in his films as ambiguous fragments. Tom Gunning describes Klahr’s work as “[d]eflecting found objects from their original univocality [...] fraying the linearity of narrative into a network of metaphors, visual puns and submerged primal scenes.”[34] As Hunter’s contours reemerge, Klahr’s fleeting images flag threats to childhood that have become mythologized in a complex web of memory that is both personal and historical.

In Daylight Moon, technology and aural memory transform Hunter’s recurring contours, as Klahr imports LP records to project spectators into veils of vinyl crackles and hazes of memory. The film unfolds in three parts demarcated by different record selections—the first two use soundtrack albums of Peter Pan and The Night of the Hunter, and the third, Nick Drake’s song “River Man”—as Klahr adopts Peter Pan’s talk of journeys and hideaways to stop-motion animate a suburban crime tale of robbery and escape. Two male figures float through noir-like sites: the robber, at first evoked with ephemeral shadows and a raincoat but then as human cutouts in “River Man”; and the fence, a money mover who wears a green visor.

The film’s found songs trigger spectators’ memories of the places and times in which they previously heard them, a process that superimposes fugitive layers onto Klahr’s images. Klahr explicitly holds space for associations: while the Peter Pan segment establishes the overarching tale of a safe robber in a getaway car, it also introduces several motivic contours, including circular objects such as spinning tires and buttons that synecdochally stand in for the titular moon. Klahr raises these synecdoches in elliptical, and not linear, patterns, paralleling Mourlet’s model wherein new and familiar audio-visual contours unfold. The spinning objects unleash a network of contours between repeated record scratches, the tires of the getaway car, and the children’s skiff. All spin off of the word “safety,” the first word that Laughton intones in Klahr’s selection from the Hunter promotional LP. The album provides the literal text of a river journey that is described more prominently in the visual sense in the other two sections. Yet, while Laughton’s narration adds a lexical audible layer to Daylight Moon, Klahr’s film does not linearly recount the children’s flight. Laughton’s gravelly yet impossibly rich bass tones impart solace but also a noir-esque monologue that sounds like a hardboiled detective who has lost the robber’s trail. The dreamlike music inspires odes to Hunter’s motivic imagery such as spider webs and dappling light, but Klahr also repeats motifs from the Peter Pan section and intercuts empty safes and cars to suggest the robber’s getaway.

A contour theory helps to parse Hunter’s transformations in Daylight Moon, as Klahr’s use of the LP does not bind his pop cultural material to visual icons. As he enlivens cultural caches with phenomenal contours, Klahr builds on the inherent energy, moods, and political commentary of his sources. When he first heard Hunter’s score, Klahr was struck by the film’s moral divides: it paints a “beautiful pastoral version of America that is also in Copland’s music. But the film gets at all this darkness of America, too, [...] at both good and evil.”[35] Similarly, Moon superimposes domains of nefarious robbers alongside wondrous river creatures. Klahr’s films often investigate how media address worldviews, which Hunter magnified for him and his wife in a New York public theater

at a particular moment where a contingent of younger people went to all these movies and had a kind of camp attitude towards them. [... While] we were willing to go with the innocence of this beautiful trip down the river and were [...] in tears and devastated, all these other people are laughing. We understood that they needed to protect themselves from the actual feeling of vulnerability, that they weren’t going to give over to the fiction in the piece to that degree.[36]

Klahr’s own work questions how different generations absorb pop cultural material, as it prompts historical associations for some and camp for others. In Daylight Moon, Klahr reanimates objects like postcards, colanders, and LPs in audio-visual contours that circumvent static leitmotifs. These elliptical motifs invite multiple generations to contemplate how twentieth- and twenty-first-century media have altered the life of the imagination, and to trace contours with childlike verve—as the account below does from my millennial and musically-trained perspective.

Klahr’s play with found sounds and objects overturns the soundtrack’s typical subservience to the image—as with many avant-garde filmmakers who use asynchronous sound.[37] Music is integral to Klahr’s filmmaking process, but critics rarely treat it in any detail.[38] Since the late 1980s, Klahr has created what he calls aural montage, pairing pre-existing tracks of popular and classical music according to certain themes. Most often in his films, he sets the musical montage first and then cuts the images to the sounds, tweaking levels and timings intuitively so that spectators can “hear the intent, but sensations and meanings slide in and out [... in] overtonal effusions.”[39] Besides invoking Eisenstein, he also echoes Bruce Conner and Kenneth Anger’s uses of pre-existing music, avoiding 1:1 correlations of images and sounds to probe their immanent content. Klahr sculpts pop cultural material according to his previous engagement but also considers the various ways that others have absorbed musical and visual objects. Like Mourlet’s defamiliarizing crescendos, crackles of found sound spark contextual contingencies and myriad worldviews.

This new, elliptical tale at once solicits audio-visual memory of Hunter but also transforms its aural traces. Klahr begins the second section of Daylight Moon with Preacher’s otherworldly moan, which spells danger not only for the children but also for Klahr’s safe robber. In Klahr’s words, “the character of Preacher [...is] not going to be forgotten, but I’m also creating a new narrative that it’s part of.”[40] Instead of showing a contorted face like Preacher’s, Klahr inserts a black button which, in shadow, looks like a record disc that spins in tandem with the jumping decibels of his voice. At other points in the film, Klahr substitutes black buttons as muses for the moon that hover over different backgrounds. The disc approximates a narrating figure, but only fleetingly, more like Laughton’s animals along the riverbank than the Preacher: shots of the disc are quick and often only link patterned backgrounds. Attention to such contours help us follow the disc and its aural double, the LP, as they trace contours within shots and initiate new ones.

In addition to non-human narrative agents, Klahr’s lighting effects often recall Laughton’s shadow/safety play. During the eerie chorus of voices that erupt after Preacher’s moan, a beam of light darts across vacillating numbers and then illuminates an open, empty safe. The spotlighted safe orchestrates aural mimicry when Laughton narrates, “safety, and the moonlight vision of the sleeping children in their small arc of safety, and Pearl cradling the precious doll in her small arms, dreams a child’s gentle dream.” Klahr’s choice to begin Laughton’s voiceover mid-sentence with the word safety accentuates the safe as a leitmotif and recalls its double in Hunter—Pearl’s doll that hides her father’s stolen money. Klahr pays homage to Pearl’s role as a safe-keeper as he pans down a curving highway to usher in her lullaby. The elegant swoop over the road highlights the journey motif of Laughton’s narrative but also calls up the fragility in “Pearl’s” tentative voice. Metonymic contours complement the textures of Laughton and Pearl’s voices—while she sings, a silver shadow trembles in the moon’s place. Similarly, frequent shots of the car seem to stand in for the children’s and robber’s getaway rig. Yet Klahr persistently intercuts playing cards, dominoes, and curved highways to evade 1:1 correlations. When the Hunter section ends, Preacher’s fate motif ushers in shots of a man’s shadow and the steering wheel, as if to associate the car with crime. Concurrently, homages to Hunter continue with brief cuts to starry skies, which Klahr created by spinning a colander on his lightbox (in later shots, he recounts, “you see the handle of the colander, exposing its own illusionism”[41]). As imagery from Hunter interrupts Klahr’s succession of crime scene images, new valences of a suburban film noir emerge from the surprising textures that mediate sights and sounds.

Daylight Moon’s mise-en-scène of childlike wonder and melancholic sentimentality becomes increasingly legible through Hunter’s maternal lullaby, which begins when the black disk spins up to a blueprint marked with the word “entry.” Besides the suggestion of entering “the womb of safety”—as Grubb described the river—in Klahr’s world, White’s lush voice ignites stop-motion animation of variously colored dominoes that change in the blink of an eye. As White sings, “Hush, little one, hush,” chips of paint ebb and flow over dark plastic. The pace of changing colors parallels those of vocal pitches and vibrato to highlight dominoes’ contingent pleasures, such as when the fortuitous selection of a matching block creates a new pair. Ecstatic chance also occurs on the lyrics “morning soon” when Klahr draws the lens over colorful dots on a crumpled sheet of paper. Like Hunter’s riverscape lighting, dancing dots soothe the previously frenetic motions of escape embodied by the rapidly color-changing dominoes. When Laughton’s voice reads, “and then a night when weary of river dreams children seek shelter,” Klahr dapples light over the interior of the car. In a give-and-take of consonance and dissonance, this repetitive dot play seems to suggest that the car has become the children’s shelter, but Klahr’s double valances of threat and safety also reassert the robber’s getaway. As Laughton’s voiceover fades out to the strums of Nick Drake’s guitar, “River Man” continues to superimpose spider webs, cars, and blurred dots with the robber’s sly figurations and the visor-wearing fence, but at a quicker pace with Drake’s guitar that recalls Hunter’s euphoric river escape.

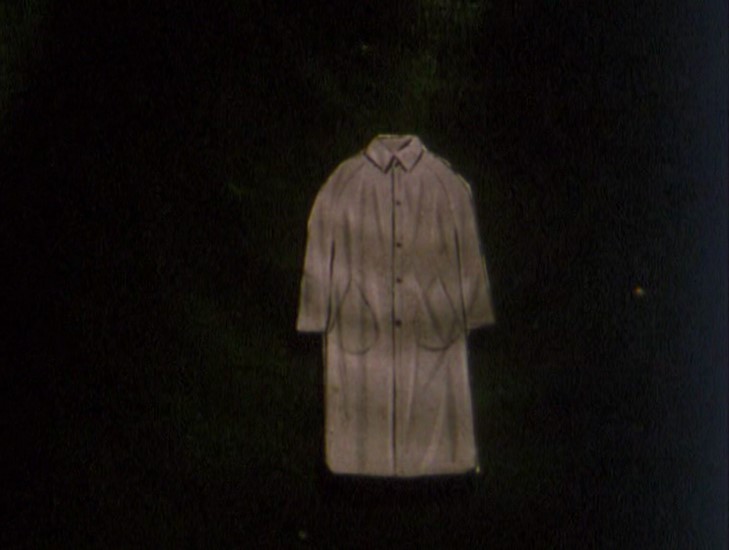

Klahr’s simultaneously mimetic and fantastic shadowed figures homage the looming Preacher and mythic creatures of the children’s river journey. With only glimpses of the robber’s shadow, it is difficult to grasp how he functions in Klahr’s story until he becomes the cut-out “river man” of Nick Drake’s eponymous lyrics. Yet however brief, evocations of human forms come alive in Klahr’s collage of contingency. Shots of the raincoat, for example, suggest the possibly villainous man who might occupy it: although it first strikes the eye as an empty, disconnected object, it vibrates with the hint of a spectral body, especially when paired with Schumann’s Preacher motif. Unlike Godard filling the female mouth with stereotypes, the plain coat—a World Book Encyclopedia image—can be filled with more than just the robber’s shadow or the evocation of Preacher; its Peter Pan collar, for example, conjures the child’s play of the titular character. Shaded by aural contours and embodied memories, capacious collage images inhabit a host of graphic, affective, and often gendered meanings.

The frayed edges of Klahr’s cutouts—and accidental colander handles—unfetter his motifs from limiting readings of leitmotifs that would focus primarily on archetypes. While Klahr respects the iconicity of his sources, he also unveils contingent threads through music to create a tangible experience of the world by appealing, via domino games and quick sound-image associations, to a spectator’s adoption of childlike exploration. Musical contours transform so-called lowbrow images of suburban adventure to plumb the depths of human nature. They evoke the ways that children learn about elements of the world, such as rubbing all sorts of objects between their fingers to explore them without deliberate goals—like Klahr’s interplay of surface and daydream, and Mourlet’s paradigm of absorbed fascination in mise-en-scène. As Klahr entwines Hunter’s music and images to solicit contingent associations of child’s play, he echoes Mourlet’s and Sartre’s self/other paradigms, where viewers momentarily plunge into unfamiliar worlds.

Contoured Mise-en-Scène: An Aural Worldview

In engaging spectators’ aural memories to layer meanings onto ephemeral contours, Daylight Moon exemplifies how found sounds reanimate visual surfaces as gazing pools wherein audiences project their memories and experiences. Music conjures real-world encounters indeterminately, always contingent on spectators’ uniquely-positioned sensoria. Similarly eschewing objective correlations, Klahr’s moving collages retain the trails of still, small voices and things: his contoured camera movements, shadow play, and found sounds multiply associations and dissociations as audio-visual contours at once stem from the spectator’s memories and the director’s writing hand. Thus, mise-en-scène contours situate spectators as simultaneously self and other to trigger surface-to-depth shifts of optical and aural worldviews.

The oxymoron “aural worldview” attempts to make obscure sense mechanisms legible: as sound impacts bodies in tactile and kinesthetic ways, contours overthrow culturally determined ways of knowing to encourage hybrid meetings of worlds. While Klahr and Godard’s remediations call up divergent histories and ideologies, their manipulations make found sounds’ indexical and associative capabilities tangible for different generations. Klahr retains the vinyl crackles of Laughton’s record to portray it as a relic of child’s play but also adult morality; Godard’s overloud sounds pastiche those of Hunter to grapple with fleshly fantasies. Both appeal to multisensory memory to approximate children’s imaginary journeys: playful sync points intensify and complicate spectatorial identification with the film’s world. These filmmakers’ audio-visual contours posit film sound as a porous sieve that variously inhabits on- and offscreen bodies through superimposed screens of audio-visual and corporeal memory. With embodied connections to historical, technological, and social objects—and manifold consonances and dissonances for spectators—found sounds recontour films with an array of worldviews.

Author Biography:

Amy Skjerseth is a Ph.D. Candidate in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. Previous publications include an [in]Transition audio essay, “Catching Flies and Catching Memories: The Skin-Crawling Sounds of Yoko Ono’s Fly (1970),” and an essay on sound in It Follows in Spectator. Her dissertation, “The Portable Pop Archive in Experimental Cinema: Technological Transformations of Aural Memory,” examines American and British artists who recast pop music in postwar avant-garde films up to visual albums. From overdubbing to deepfakes, she argues that a vital strand of media practice uses found sound to politicize historical moments by appealing to personal and collective memory.

Notes

The author wishes to thank the community of readers who helped shape this article. This work originated in Tom Gunning’s “What was Mise-en- Scène?” University of Chicago seminar, which featured Gila Walker’s translation of the Mourlet essay I cite. Tom also introduced me to Lewis Klahr, who graciously shared his time and work with me in phone, email, and in-person conversations. Daniel Morgan, my advisor, generously and astutely saw this work through from a post-seminar paper to its final form. Members of my reading group based in the University of Chicago Music Department read an early draft, and attendees of the Mass Culture Workshop read a revised one, with special thanks to organizers Tanya Desai and Sophie Lynch, Tom Gunning as respondent, and interlocutors Dominique Bluher, Jenisha Borah, Steven Maye, Richard Neer, David Rodowick, and Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky. Lastly, my gratitude goes to Caryl Flinn, who offered extensive feedback (especially around the case of “the Mitchum Man”), and to the attentive guidance of the editors of Film Criticism and the anonymous reviewer of this essay.

Hugo Münsterberg, The Film: A Psychological Study (New York: Dover Publications, 1970 [1916]).

John Gibbs and Douglas Pye, “Revisiting Preminger: Bonjour Tristesse (1958) and Close Reading,” in Style and Meaning: Studies in the Detailed Analysis of Film, eds. Gibbs and Pye (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), 111. Gibbs and Pye cite David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 13

See Theodor Adorno and Hanns Eisler, Composing for the Films (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005 [1947]).

This essay builds on Berthold Hoeckner’s concept of “double projection,” or the mental images that viewers project from prior contexts of hearing familiar musical pieces used in films. See Film, Music, Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), Chapter 3. Whereas Hoeckner describes “music’s mnemonic powers of reprojection” mainly in relation to visual, musical, and mental registers (70), I accentuate multisensory effects of audio-visual contours: sonic textures elicit embodied memories to sensually engage viewers in mise-en-scène.

Michel Mourlet, “On a Misunderstood Art («Sur un art ignore»),” trans. Gila Walker, Cahiers du cinéma 98 (August 1959).

See Peter Kivy’s claims that melodic contours resemble bodily comportments of emotions in Sound Sentiment: An Essay on the Musical Emotions (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989).

Germaine Dulac, “Aesthetics, Obstacles, Integral Cinégraphie,” trans. Stuart Liebman, in French Film Theory and Criticism: A History/Anthology, vol. 1, 1907–1929, ed. Richard Abel (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988 [1926]), 394.

Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 71.

Walter Schumann, “The Night of the Hunter,” Film Music Notes 15, no. 1 (1955): 13.

Walter Schumann, “The Night of the Hunter,” Film Music Notes 15, no. 1 (1955): 15.

Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1976), 62.

Thomas Elsaesser, “Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama,” in Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, Fourth Edition, ed. Gerald Mast, Marshall Cohen, and Leo Braudy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 533.

Rick Altman, for example, details how indexed melody books helped pianists to switch between funeral marches and chase scenes. His Silent Film Sound nuances historical trajectories of leitmotifs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Words, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 123.

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Words, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 123-4.

Jeffrey Couchman, The Night of the Hunter: A Biography of a Film (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2009), 156.

Grove Music Online, s.v. “Reed Instruments,” by Klaus Wachsmann, 2001, accessed August 11, 2019, https://doi-org.proxy.uchicago.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.23045.

Grubb to Laughton, April 19, 1954, p. 6, The Night of the Hunter study collection, quoted in Couchman, Hunter, 157.

Sergei Eisenstein, “The Fourth Dimension in Cinema,” in S.M. Eisenstein: Selected Works: Writings 1922-1934, trans. and ed. Richard Taylor (London: British Film Institute, 2006), 183; 191. For Eisenstein, overtonal montage results when images and editing rhythms collide to produce sensed and psychical vibrations for spectators: these parallel the physical impressions left by the acoustical phenomenon of overtones. In Alexander Nevsky (1938), Eisenstein and Prokofiev intertwined graphic and musical contours, but deterministically coordinated certain melodies with image arcs (“Vertical Montage” in S.M. Eisenstein: Selected Works: Towards a Theory of Montage (London: British Film Institute, 1994), 398; 393).

Richard Neer closely recounts each of these superimpositions in “Godard Counts,” Critical Inquiry 34, no. 1 (Autumn 2007): 153-159.

Translation from the English subtitles of Histoire(s) du cinéma, dir. Jean-Luc Godard (London: Artificial Eye, dist. World Cinema Ltd., 2008), DVD.

See, for example, Richard Wolin, “Benjamin’s Materialist Theory of Experience,” Theory and Society 11, no. 1 (January 1982): 17-42.

For more on sound’s role in Godard’s superimpositions, see Daniel Morgan’s study, Late Godard and the Possibilities of Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012)—on Delpy’s voice especially, see pp. 161-165—and Nora M. Alter, “Mourning, Sound, and Vision: Jean-Luc Godard's JLG/JLG,” Camera Obscura 44, vol. 15, no. 2 (2000): 75–103.

Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 28.

Female voices long have been fetishized in cinema studies as speaking the “truth” of a woman’s interiority, from the Echo and Narcissus myth to Singin’ in the Rain (1952). See, for example, Mary Ann Doane, “The Voice in Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space,” Yale French Studies 60 (1980): 33-50; Amy Lawrence, Echo and Narcissus: Women’s Voices in Classical Hollywood Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991); and Jennifer Fleeger, Mismatched Women: The Siren's Song Through the Machine (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Tom Gunning, “Towards a Minor Cinema: Fonoroff, Herwitz, Ahwesh, Lapore, Klahr and Solomon,” Motion Picture 3, nos. 1-2 (1989-90): 2-5; 5.

Found sound long has been used in film, especially in the American avant-garde—in 1963, for example, Kenneth Anger willfully appropriated mainstream pop songs in Scorpio Rising, and Barbara Rubin instructed projectionists to play AM rock at random during screenings of Christmas on Earth.

Analyses of Klahr’s use of sound usually only occur in some detail in close readings of films; see, for example, Lilly Husbands, “A Hermeneutic of Polyvalence: Deciphering Narrative in Lewis Klahr’s The Pettifogger (2011)” in Experimental Animation: From Analogue to Digital, eds. Miriam Harris, Lilly Husbands, and Paul Taberham (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2019), 169-185.