Sons of God: Postwar Gender and Spirituality in Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Examining Terrence Malick’s 2011 film The Tree of Life through a lens attuned to the gender and religious politics of early Cold War America illuminates how the thematic juxtaposition at the film’s heart—nature vs. grace—captures anxieties that pervaded American culture in the fifteen years following World War II.

At a key moment in the 2011 feature film The Tree of Life, the character Jack O’Brien sternly instructs his eldest son and namesake, “You are not to call me ‘Dad.’ You will only call me ‘Father.’” The directive is a nod to Christian hierarchy in a film replete with religious references. But Mr. O’Brien’s dogmatic statement reveals more than his theological outlook. It also reminds the viewer that in the cosmological makeup of the postwar American family, the man at the head of the dinner table was an earthly deity, an alternately benevolent and wrathful force with extraordinary powers to create, institute, and enforce order.[1]

Scholarly examinations of The Tree of Life have tended to focus on the film’s spiritual and philosophical themes, with a particular sensitivity to issues of sin and redemption, morality, phenomenology, cosmology, and eternal life.[2] While understandable, that preoccupation with the sacred has overshadowed other crucial elements of the film and caused some scholars to fall victim to cliched readings of writer-director Terrence Malick’s work, what Simon Critchley identified as “three hermeneutic banana skins”: searching for meaning in Malick’s hermitic persona; overanalyzing Malick’s personal experiences as a student of philosophy; and identifying a “philosophical metalanguage” that will explain his work.[3]

In an effort to avoid such pratfalls, this essay seeks to move past such philosophical speculation in favor of historical close reading. For example, one key factor largely overlooked by prior academic work on The Tree of Life is the degree to which the film’s primary tension is explicitly gendered. Furthermore, scholars have generally neglected to discuss the film as the period piece it is—possibly because the themes at its heart are implicitly rendered as timeless. However, The Tree of Life makes those eternal questions all the more provocative because its central narrative thrust is historically-bounded. It is not mere coincidence that the film’s cosmological explorations are grounded in a specific place and time, namely suburban Texas of the 1950s. The following examination argues that any understanding of the film that fails to account for the gender politics of early Cold War America is incomplete. In so doing, this article demonstrates how The Tree of Life uses the thematic juxtaposition at its center—nature vs. grace—to capture the anxieties about gender roles that pervaded American culture in the fifteen years following the end of World War II. Examining that key friction through the lens of gender illuminates how the film expresses the universal through the specific, that is: how the history of life on earth can be seen in the dramas surrounding one nuclear family.

At the center of The Tree of Life stand the fictional O’Brien family of Waco, Texas: Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien (played by Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain, respectively) and their three sons, Jack, Jr. (Hunter McCracken), R.L. (Laramie Eppler), and Steve (Tye Sheridan). As the three O’Brien boys progress toward adulthood and their parents attempt to tutor them in the ways of the world, they encounter challenges both typical and extraordinary: the mundane toil of daily chores, the need to impress their peers, the development of sexual feelings, the negotiation of parental authority, the tragedies which befall friends and neighbors. The O’Brien family’s experience is further explored in a handful of scenes depicting the spiritual malaise of the adult Jack O’Brien, Jr. (Sean Penn) as he navigates life as an architect in modern-day Houston. Interspersed with the family-focused narrative are a number of scenes depicting the birth of the universe and the dawn of life on Earth, including exploding stars, crashing meteors, world-shaping storms, and the development of the planet’s early flora and fauna. Through a nonlinear narrative, the film asks the viewer to ponder weighty questions about the nature of humanity, the immortal connection between brothers, fidelity, and the meaning of life. One critic described the resulting 139 minutes as “a cinematic symphony more than a classic narrative film,” while another derided it as a confusing, navel-gazing “taffy pull.”[4]

Sonorous or sticky, the film’s narrative core unfolds during one of the most complex, paradoxical moments in American history. The immediate postwar era represented a unique confluence of opportunity and uncertainty in the United States. Despite the nation’s victory in World War II, the end of the conflict thrust American society into a period of instability. The international threat presented by the Axis powers disappeared, but another from the Soviet Union rose to take its place. The mobilization necessitated by World War II had significantly altered the way Americans lived and worked, and a return to peacetime footing required a similar upheaval. The millions of young Americans returning from overseas caused an unprecedented spike in both the rate of marriage and number of births. As part of this shift, historian Elaine Tyler May notes, “postwar American society experienced a surge in family life and a reaffirmation of domesticity that rested on distinct roles for women and men.”[5] This revived domesticity was buttressed by fears of nuclear Armageddon. “The home,” May writes, “represented a source of meaning and security in a world run amok. Marrying young and having lots of babies were ways for Americans to thumb their noses at doomsday predictions.”[6] This domestic impetus was so strong that it contributed to a national housing shortage during the half-decade following the end of World War II.[7]

At the same time, American gender standards—and those governing masculinity in particular—were on the verge of being redrawn. Even before World War II, social commentators were voicing worries that overbearing or coddling mothers were stunting the masculine growth of their sons. Those fears were given a name—“Momism”—by the social critic Philip Wylie in his 1942 book Generation of Vipers. Wylie held that modern mothers held an inordinate amount of influence over their sons. This overprotective attitude meant that the son was “shielded from his logical development through his barbaric period, or childhood... [and] cushioned against any major step in his progress toward maturity.” Therefore, any sympathy the son would have for others was transmuted by the mother “into sentimentality for herself.”[8] Momism became a pop-psychological phenomenon and deeply influenced the American social conversation during the 1940s and 1950s. As historian James Gilbert has demonstrated, the fifteen years following World War II witnessed a surge in fears that American men were becoming feminized. Many Americans feared that such feminization would ultimately result in rampant homosexuality.[9] That anxiety metastasized as the Lavender Scare, a series of interconnected purges undertaken by federal, state, and local authorities against government employees accused of homosexuality. According to historian David K. Johnson, thousands of individuals were fired or forced to resign from their jobs as a result of the witch hunt.[10]

Even though Gilbert and others have argued that the 1950s did not feature a “single, prevailing, agreed-upon norm of masculinity,” certain aspects of masculinity achieved dominance over others, particularly within specific racial or socioeconomic groups.[11] In the words of Michael Kimmel, “all American men must... contend with a singular vision of masculinity, a particular vision that is held up as the model against which we all measure ourselves.”[12] Scholars often refer to this ideal version as “hegemonic masculinity,” employing a term first introduced by the sociologist R. W. Connell in the 1980s. For white, middle-class men in 1950s America, hegemonic masculinity valued aggression, competitiveness, confidence, financial stability, and physical fitness. The era’s other sociocultural phenomena, such as the aforementioned fears surrounding feminization and homosexuality, helped narrow society’s definition of the masculine. These limitations were particularly stringent for the white, middle-class men (such as Mr. O’Brien) who sought to climb the postwar corporate ladder. In addition, hegemonic masculinity was further defined by its regional associations. The O’Brien’s location in Texas places them at the crossroads of two American regional cultures—the Southern and the Western—which have especially conservative understandings of gender roles.

The other piece of historical context necessary for understanding The Tree of Life is the development of American spirituality in the early Cold War era. Between 1940 and 1960, church membership in the United States grew from 64.5 million to 114.5 million—an astounding leap.[13] According to religious historian Robert Wuthnow, that growth was partially attributable to the war itself, which “served as a symbolic demarcation of time, a liminal period associated with the nation’s rite of passage from adolescence to maturity, a special moment in history that separated the old from the new... It was as if the stormy years of war had purged the air of traditional assumptions, allowing a fresh wind to blow across the religious mindscape.”[14] To many Americans, the Allies’ triumph over fascism in World War II had confirmed the assurance displayed on a prominent wartime recruitment poster featuring the boxer Joe Louis: “we’ll win because we’re on God’s side.” Religious devotion also helped Americans refine their sense of national identity in the context of a changing world. Seeking to distinguish the pious United States from its atheistic Communist foes, President Dwight D. Eisenhower “authorized the inclusion of the phrase ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance and the stamping of ‘In God We Trust’ on currency.”[15]

However, Wuthnow notes that the sense of promise and purpose fostered by postwar American religion was limited because “an underlying fear of imminent peril was also evident. Religious discourse was filled with prophecies of doom. Peace was certainly better than war, and prosperity was preferable to hardship, but no one knew how long these comforts would last.”[16] Though the end of the world had been predicted before, the advent of nuclear warfare made that threat particularly palpable. Historian Peter Allitt echoes Wuthnow’s conclusions, arguing that the 1950s witnessed an “upsurge in religiosity” driven by a “fear of annihilation in a nuclear war [which] was so intense that it drove anxious men and women back to churches and synagogues for reassurance.”[17] In the American imagination, the placid suburban landscape was also pockmarked with homemade bomb shelters. This paradoxical approach to religion spoke volumes about the nation’s mood during the 1950s: the gilding of domestic tranquility masked fundamental sociopolitical anxieties.

It is significant that The Tree of Life is built around that historical moment. From one perspective, the universal nature of the film’s themes granted writer-director Malick the freedom to set it in any time period. Malick’s decision to set the film in the immediate postwar era reflects not only his experience with that period, but the uniqueness of that moment in American history with respect to socioeconomic change, shifting gender relations, and the existential dread prompted by the advent of nuclear warfare. While the search for universal meaning and order may be perennial, the exact character of those questions shifts according to immediate circumstance.

Much of the situation facing the O’Brien family is likely inspired by Malick’s own experiences, with the character of Jack O’Brien, Jr. sharing a number of autobiographical similarities with the film’s creator. Like the fictional Jack, Malick grew up as part of a middle-class family in the southwest (Oklahoma and Texas) during the 1950s and was the eldest of three sons. One of Malick’s younger brothers, Larry, died of suicide at the age of nineteen (the age at which R.L. O’Brien perishes in a car accident in The Tree of Life), and his other younger brother, Chris, was badly burned (again, like a character in the film) in an automobile accident as an adult. Like Mr. O’Brien, Malick’s father played organ at the family’s local church after failing to establish himself as a professional musician, and he was forced to move the family at least once due to his job at Phillips Petroleum.[18] These personal connections lend an additional air of intimacy to a film already teeming with emotion.

That sense of the personal is most palpable in the scenes featuring the O’Brien family, moments which stand as the film’s emotional centerpiece: playing in their suburban yard, sitting around their dinner table, shopping for groceries in downtown Waco, attending church, swimming at the public pool. The O’Brien family’s experiences introduce viewers to the work’s central thematic question, a dialectic presented near the outset of the film in a voiceover by Mrs. O’Brien. “The nuns taught us there were two ways through life,” she recalls, “the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow.” She continues, explaining the difference between those paths:

Grace doesn't try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. Get others to please it too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it, when love is smiling through all things. They taught us that no one who loves the way of grace ever comes to a bad end.

It is significant that this fundamental question is presented as an individual choice, and that there is no third (or blended) path available. In that context, this essential philosophical question becomes projected onto the O’Brien boys, especially Jack. Which path will they choose? Mrs. O’Brien’s belief that her sons have that choice—and that it will determine the course of the rest of their lives—underscores how important parental guidance will be as they select their course.

Figure 3: Mrs. O’Brien (Jessica Chastain) compares the ‘way of nature’ and the ‘way of grace’ in a voiceover.

The friction between grace and nature has deep roots in Christian theology.[19] The most influential explication of the concept appears in Chapter LIV of Thomas à Kempis’s fifteenth century devotional The Imitation of Christ. In the Christian construction, “nature” is understood to be the nature of man, which has been corrupted as a result of original sin. Grace, on the other hand, is linked to the forgiveness of those sins and a closer connection to God. Kempis, a German priest, first notes that “all men desire that which is good,” but suggests that men are often attracted to spiritual modes which ultimately hinder their ability to achieve goodness. Kempis introduces the difference between nature and grace thusly:

Nature is crafty, and seduceth many, ensnareth and deceiveth them, and always proposeth herself for her end and object. But grace walketh in simplicity, abstaineth from all show of evil, sheltereth not herself under deceits doeth all things purely for God's sake, in whom also she finally resteth. Nature is reluctant and loth to die, or to be kept down, or to be overcome, or to be in subjection or readily to be subdued: But grace studieth self-mortification, resisteth sensuality, seeketh to be in subjection, is desirous to be kept under, and wisheth not to use her own liberty. She loveth to be kept under discipline, and desireth not to rule over any, but always to live and remain and be under God, and for God's sake is ready humbly to bow down unto all. Nature striveth for her own advantage, and considereth what profit she may reap by another. Grace considereth not what is profitable and convenient unto herself but rather what may for the good of many. Nature willingly receiveth honor and reverence. Grace faithfully attributeth all honor and glory unto God.[20]

This understanding of the relationship reflects Malick’s outlook in The Tree of Life, or—at least—the perspective that Mrs. O’Brien was taught by the nuns. Individuals following the path of grace see the beauty in all things, deeply appreciate their existence, and display wonder at the world around them, but they can be meek and docile. Followers of the way of nature feel a greater degree of control over their lives and display more resiliency, but are more aggressive, competitive, and combative. It is important to note that in Malick’s construction, followers of the way of nature—despite its name—display less reverence for the beauty of nature than those who follow the way of grace. Adherents to the way of nature are more focused on controlling the natural world and demonstrating power over it than they are on appreciating its majesty. The iteration of this philosophy that The Tree of Life presents is not without its paradoxes. But those contradictions mirror the mystery of life itself, which—bold as it may seem—is an essential focus of the film.

Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien personify the two paths, she representing the way of grace and he fulfilling the way of nature. It is a pairing that highlights the gendered nature of their respective approaches. Mrs. O’Brien’s way of grace is stereotypically feminine: soft, tender, accepting, domestic, noncombative, and playful. These characteristics are particularly readable in how Mrs. O’Brien interacts with her sons. She guides them with a gentle touch, lounging with them in the grass, chasing them around the house, rousting them from bed by slipping ice cubes down the backs of their nightshirts. She emphasizes their connection with nature, pointing to a sapling in the family’s yard and telling toddler Jack that he’ll “be grown before that tree is tall.” Her values are revealed in the advice she gives her sons in a voiceover: “Help each other. Love everyone, every leaf, every ray of light. Forgive.” Later, her voiceover continues: “The only way to be happy is to love. Unless you love, your life will flash by... Do good to them. Wonder. Hope.”

The cinematographic choices of Director of Photography Emmanuel Lubezki highlight Mrs. O’Brien’s gracefulness and femininity. She is surrounded by rays of light, creating an angelic halo when they pass through the edges of her dress and hair.[21] The camera floats around her, meandering from her face, to the sky, to sunlight passing through the limbs of a tree. Those movements connect her with the natural world while highlighting her privileged position in its hierarchy, presenting her as an ethereal being that both embraces and transcends the landscape surrounding her. Lubezki’s camera work sanctifies her in a way that recalls Catholic artists’ veneration of the Virgin Mary. The Blessed Mother is also suggested by other aspects of Mrs. O’Brien’s filmic appearance. She is largely desexualized, never appearing in a scene featuring sexual intimacy, while the iridescent dresses she wears throughout the film are flattering but demure. She also appears in moments of veneration: in the film’s final scenes she is attended to by angelic figures as she “gives” her son to the Lord.

Though she is a sanctified figure, the limits of Mrs. O’Brien’s approach are revealed when her husband leaves town on an extended business trip. She quickly loses control of her sons in his absence, and the boys turn wild: playfully torturing their mother with a lizard they find outside, screaming and running around the house like banshees, and delightfully performing acts—like slamming the porch door—that their father explicitly prohibits. Jack’s actions grow increasingly violent. He breaks the window of a neighbor’s shed with a rock, and later ties a frog to a rocket firework and lights it, killing the animal in the resulting “experiment.” Unchecked by his father’s oversight, Jack’s approach to the natural world becomes one not of wonder but of dominance. Shortly after his father’s return, Jack’s violent experimentation climaxes in a scene where he convinces his brother R.L. to place his finger over the muzzle of a BB gun and then pulls the trigger. Jack is immediately remorseful, later inviting R.L. to mete out a physical reprisal: “You can hit me if you want. I’m sorry. I’m your brother.” Jack’s recognition of his brotherhood brings to mind the question Cain poses to God in Genesis; in this instance, Jack clearly recognizes that he is, in fact, his brother’s keeper.

Mr. O’Brien is presented as nothing if not controlling, and his embodiment of the way of nature centers around characteristics considered stereotypically masculine. He is aggressive, unbending, competitive, domineering, serious. He regards life as a constant struggle, and believes that success will only come to those with the fortitude to survive the crucible. Mr. O’Brien’s worldview is deeply influenced by the constant letdowns that have punctuated his life: his failure to become a professional musician, his inability to win patents for his various inventions, his fraught relationship with his wife and sons, and his powerlessness to save his own job when the plant he works for closes. In these constant tests of his faith, Mr. O’Brien is not unlike Job, and he even shares the initials of the Biblical sufferer: Jack O’Brien. A quotation culled from two verses of the Book of Job also serves as the film’s epigraph: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth?... When the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”[22]

As with his wife, Mr. O’Brien’s philosophy is most apparent in how he relates to his sons. When Jack lets the porch door slam, Mr. O’Brien makes him silently close it fifty times. When Jack fails to properly weed the family’s yard, Mr. O’Brien has him repeat the chore. When R.L. questions his father at the dinner table, Mr. O’Brien physically attacks him. When Jack tries to protect his younger brother during that onslaught, Mr. O’Brien shuts him in a closet. Later, Mr. O’Brien explains his actions to Jack, cautioning him, “Your mother’s naïve. It takes fierce will to get ahead in this world. If you’re good, people take advantage of you.”

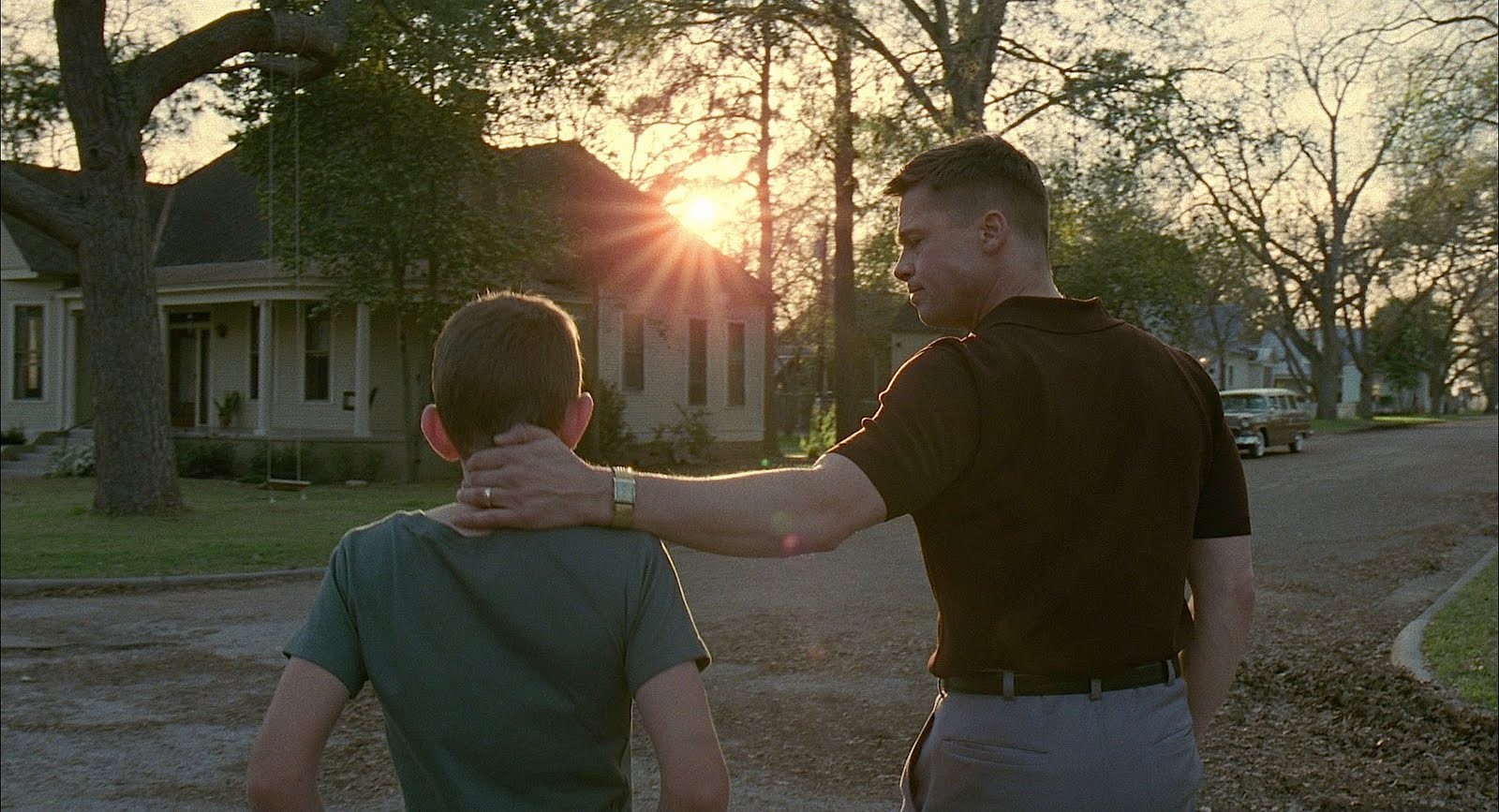

In one telling scene, Mr. O’Brien takes his sons into the yard and tries to teach them to box. He shows them how to throw a punch and then repeatedly slaps the side of his own face and repeats, “hit me.” Jack tries, but Mr. O’Brien smacks his son’s jabs away, a means of demonstrating that while Jack wants to be a man—or even think himself one—manhood is still a distant goal for him and his father retains firm control over the house. During his turn, R.L. cannot bring himself to throw a punch, confusedly regarding his father as Mr. O’Brien repeats, “hit me.” R.L becomes frozen, unable to strike at his father even in practice. Mr. O’Brien eventually gives up, telling R.L. to “go on” and play elsewhere. Not only does this boxing lesson demonstrate the centrality of physical prowess in Mr. O’Brien’s understanding of manhood, it shows the boys’ hesitancy surrounding and inability to fully embrace their father’s aggressive, “way of nature” approach.

Figure 5: Mr. O’Brien (Brad Pitt) teaches his sons Jack, Jr. (Hunter McCracken) and R.L. (Laramie Eppler) to box.

Lubezki’s cinematography is similarly instructive in characterizing Mr. O’Brien and his commitment to the way of nature. During scenes featuring Mr. O’Brien the camera movement becomes rougher and more direct, abandoning the smooth, meandering tracking shots used to film his wife. Camera placement is often moved upward, to Mr. O’Brien’s eye-level, giving the viewer the sensation of looking down on the O’Brien boys when they share scenes with their father. Even when sitting in church, Mr. O’Brien appears unhumbled; his back is straight and proud, his movements confident. Tellingly, the light that enshrouds Mrs. O’Brien does not similarly bless her husband.

Despite his pride, Mr. O’Brien is pock-marked with feelings of failure and guilt. His professional failures as a musician and inventor haunt him, and toward the end of the film he tells Jack, “You boys are about all I’ve done in life. Otherwise I’ve drawn zilch. You are all I have.” A beat later, he unconvincingly adds, “You’re all I want to have.” The professional crisis prompted by the closure of the plant at which he works leaves him with the difficult choice between either resigning his position or moving his family a great distance to take a “job nobody wants.” The portion of the film set in the 1950s closes with Mr. O’Brien choosing the latter route, with the boys longingly regarding their old neighborhood through the back window of the family car as it pulls away from the only home they have known. In a voiceover, Mr. O’Brien laments, “I wanted to be loved because I was great, a big man. I’m nothing. Look. The glory around, trees, birds. I dishonored it all. Didn’t notice the glory.” He concludes that he has been “a foolish man,” mourning the fact that he let himself “get sidetracked” from his goal of becoming “a great musician.”

Figure 6: Mr. O’Brien and his three sons.

Mr. O’Brien’s masculinity—and the way it is challenged by circumstance—is unmistakably connected to the historical moment at which he lives. His masculine sense of self is predicated on experiences that are often presented as universal for men of his generation: military service (a quick shot of him in uniform suggests that Mr. O’Brien served in the Navy during World War II), heterosexual marriage, fatherhood, home ownership, gainful employment, physical aptitude, and worldliness (demonstrated through intelligence, international travel, and cultural skills). For much of the film, it is clear that Mr. O’Brien believes that he deserves a happy, fulfilling life brimming with personal and professional success because he has worked hard and done his duty as a soldier, husband, employee, father, and disciple. Despite his feelings of entitlement, Mr. O’Brien is able to partake in the bounties of postwar America—a comfortable car; a free-standing home filled with appliances (possibly financed through a federally-guaranteed loan courtesy of the GI Bill); a white-collar job with an expense account—precisely because he is a straight, white man who successfully fulfilled the masculine duties required by his country.[23]

But Mr. O’Brien is ultimately stymied by the deeper forces undergirding that economic order, forced to uproot his family as a result of fossil fuel industry’s boom-bust cycle and possibly foiled in his attempts to secure patents by corporate interests. And part of the reason he becomes “sidetracked” from his original goal of becoming “a great musician” is the pressure that is placed on him to fulfill the cultural expectations of masculinity, including becoming the breadwinner for his family. Even Mr. O’Brien’s most unambiguous victory—the peace he helped win through World War II—is called into question by the ongoing geopolitical strife of the Korean and Cold Wars.

Malick’s examination of Jack O’Brien, Jr.—specifically Jack’s efforts to choose between the way of grace and the way of nature—provides additional insight into the gendered and historical aspects of the film’s central question. If the two paths are aligned with a male/female understanding of gender, then the changes experienced by Jack’s generation grant him the opportunity to embrace a third path, specifically a different form of manhood. That opportunity for deviation was enabled by the social and economic stability members of Jack’s generation experienced.

In considering Jack from a historical perspective, it is essential to recognize his generational alignment as a Baby Boomer—that group of children born in the two decades following the end of World War II. Boomers were the largest generation in American history; historian Steve Gillon notes that between 1945 and 1964 “nearly 80 million American children were born,” and by 1959 a full thirty percent of Americans were under the age of fourteen.[24] And in spite of the anxieties born out of the Cold War, Boomers were raised in greater comfort and enjoyed more security than any prior generation of Americans. As Gillon writes,

Between 1940 and 1960 the gross national product (GNP) more than doubled, from $227 billion to $488 billion. The median family income rose from $3,083 to $5,657, and real wages climbed by almost 30 percent. By 1960 a record 66.5 million Americans held jobs. Unlike in earlier boom times, runaway prices did not eat up rising income: inflation averaged only 1.5 percent annually in the 1950s. “Never had so many people, anywhere, been so well off,” the editors of U.S. News & World Report concluded in 1957.[25]

In this climate of relative wealth and stability, Boomers like Jack were afforded the opportunity to take social risks unavailable to members of their parents’ generation. The desire to distinguish oneself from one’s parents is seemingly universal, but social commentators and historians have remarked that Boomers appear to have been more invested in rejecting traditional values than other generations, pointing to the upheaval of the 1960s as evidence. Boomers were also singular in their individualism and efforts to find self-fulfillment; as Gillon notes, “In 1940 only 11 percent of women and 20 percent of men agreed with the statement, ‘I am an important person.’ By 1990, over sixty percent of both sexes agreed with that statement.”[26]

For Jack, that individualism manifests in his efforts to balance the worldviews of his parents and chart a third path between the way of nature and the way of grace. Jack, like many men of his generation, seems to be invested in a more empathetic, emotionally-intelligent brand of masculinity, in direct opposition to the harder-edged version performed by his father. In contrast to his father, the adult Jack appears more sympathetic and emotionally expressive, talking openly about his feelings and—in the film’s final scenes—participating in moments of forgiveness and spiritual embrace. The loosening of stringent rules governing gender performance in postwar America allow Jack to traverse that third path.

Jack’s efforts to bridge the ways of nature and grace can also be seen in his choice to become an architect, selecting a profession that seeks to respect the beauty and wonder of the world while modifying the natural landscape. Jack’s office is over-engineered and features a modern design, imposing the sense of order associated with the masculine way of nature. But it includes natural touches—oversized windows bathe the space in light, unadorned blocks of wood paneling define the space, potted trees decorate conference rooms and the building’s lobby—and there appears to be a real effort to commune with nature as much as tame it. Jack’s home features a similar blurring of the line between nature and a built environment; in one scene, a woman whom the viewer can assume to be Jack’s wife uses a branch of greenery from a tree outside their window to decorate their living room. Like other films directed by Malick—including Days of Heaven and The New World—The Tree of Life portrays human efforts to shape, control, and commodify the Earth’s natural bounty. Note, too, that Mr. O’Brien’s work in the fossil fuel industry is an explicit example of that quest.

At the same time, Jack’s professional success has not insulated him from malaise. In whispered cell-phone conversations—some of which are likely with his father—Jack admits confusion and laments being career-focused. As he talks into the receiver, Jack longingly eyes a lithe, blonde officemate and tells the person on the other end of the line that he feels “like I’m bumping into walls,” a telling choice of metaphor given his profession and relationship with the natural world. In some ways, Jack’s frustration seems to stem from the fact that he cannot adequately combine his parents’ dueling philosophies. He has achieved the professional status and financial stability his father always craved, but he remains depressed. Jack is still limited by his natural desires, as his glance toward his attractive coworker suggests. It is also telling that Jack appears to have no children of his own, a decision that further differentiates him from his father and alleviates the pressure of providing spiritual and moral guidance to a new generation. Some might regard the decision to remain childless as self-interested, a common criticism leveled at Baby Boomers.

If Malick does intend to endorse one side in the nature/grace dichotomy, a possible answer can be found in the film’s grandiose, operatic climax. In that scene, adult Jack enters—or imagines himself entering—a sort of alternate universe or afterlife. The camera passes through a door, stepping from darkness to light, then enters a desert landscape punctuated by oases. Hector Berlitz’s Grande Messe des Mortes (better known as the “Requiem”) booms across the soundtrack. Besuited, adult Jack wanders through a series of rocky outcroppings, accompanied by his younger self. The camera tilts upwards and adult Jack passes through a door, finding himself on the short of a sea or large lake. Surrounded by angelic figures, he falls to his knees. People wade through the shallow surf, finding loved ones and embracing them. As Berlitz’s choir swells, adult Jack reunites with the members of his family, all frozen in their 1950s-era bodies: first his mother, then his father, then his brothers.

Figure 7: Adult Jack O’Brien, Jr. (Sean Penn) in The Tree of Life’s climactic scene.

When Mrs. O’Brien greets her middle son, R.L., the camera’s focus shifts to her. Amazed to see her deceased son in the flesh, she caresses his face. She kisses her husband on the lips and the full family embraces. In a voiceover again reminiscent of the Virgin Mary, Mrs. O’Brien whispers the film’s final lines, “I give him to you, I give you my son” as Berlitz’s non-diegetic choir sings, “Amen, Amen.” Which son Mrs. O’Brien refers to—R.L. or Jack—is unclear (it has earlier been revealed that R.L. dies in an accident at the age of nineteen). Yet in this ultimate act of grace, all members of the O’Brien family seem to forgive each other. This moment of forgiveness, this act of coming together, closes the film on a hopeful note, one that intimates that the universe does have an ultimate order to it. The penultimate shot of the film is a bridge crossing a wide body of water, perhaps representing not only Jack’s occupation but his efforts to connect his parents’ distinct approaches to the world. Before the credits roll, the camera rests on Thomas Wilfred’s video artwork “Opus 161,” an ambient, ethereal, polychromatic composition that the film uses throughout as a way to represent the divine. In the end, grace is what brings us back to God.

While Malick communicates his vision through a sort of ahistorical mysticism, his choice to set the film in a certain space and at a certain time grounds it in history. That setting means that the philosophical binary Malick presents—with its gendered overtones—cannot be understood without a close examination of that era’s attitudes toward spirituality and gender. The gendered assumptions embedded in postwar breadwinner liberalism specifically limit the life paths available to the members of the O’Brien family, even as they engage with questions whose answers feel limitless.

Author Biography

Christopher Michael Elias is a cultural and political historian who earned his PhD in American Studies from Brown University. He teaches in the Department of History at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota.

The author wishes to thank the editors of Film Criticism and the anonymous reviewer of this essay for their helpful comments on this article. The author also wishes to express his gratitude to Doug Mitchell of the University of Chicago Press for his insights on an early draft of this article—this work is published in his memory.

Examples include Jonathan Beever and Vernon W. Cisney, The Way of Nature and the Way of Grace: Philosophical Footholds on Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. (Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2016); Peter J. Leithart, Shining Glory: Theological Reflections on Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013); Peter M. Chandler, “The Tree of Life and the Lamb of God,” in Theology and the Films of Terrence Malick, ed. Christopher B. Barnett and Clark J. Elliston (New York, Routledge, 2016), 205-217; and Joshua Nunziato, “Eternal Flesh as Divine Wisdom in The Tree of Life,” in Theology and the Films of Terrence Malick, ed. Christopher B. Barnett and Clark J. Elliston (New York, Routledge, 2016), 218-231.

Simon Critchley, “Calm: On Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line,” Film Philosophy 6.48 (Dec. 2002): <www.film-philosophy.com/vol6-2002/n48critchley>.

Lee Marshall, “Review: The Tree of Life,” Screen Daily, May 16, 2011; Rex Reed, “Evolution, in Real Time! Terrence Malick’s Ponderous The Tree of Life Ponders the Meaning of Life,” The New York Observer, May 24, 2011.

Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 6.

Rosalyn Baxandall and Elizabeth Ewen, Picture Windows: How the Suburbs Happened (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 87-88.

Philip Wylie, Generation of Vipers (New York: Farrar and Reinhart, 1942), 208.

James Gilbert, Men in the Middle: Searching for Masculinity in the 1950s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 166-167.

Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History 3rd Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 4.

Robert Wuthnow, The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith since World War II (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 29.

Wuthnow, The Restructuring of American Religion, 37. Along with the shifting demographics described by May, that optimism was visible in a robust economy built on freely-available credit and a series of cultural touchstones portraying domestic bliss on radio and television: The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (the radio program ran from 1944-1954, the television show from 1952-1966); Father Knows Best (radio, 1949-1955; television, 1954-1960); I Love Lucy (television, 1951-1957); The Ruggles (television, 1949-1952); and The Life of Riley (radio, 1944-1951; television, 1949-1950 and 1953-58).

Patrick Allitt, “Religion since 1945,” in The Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History, ed. Michael Kazin (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 454.

Stuart Kendall and Thomas Dean Tucker, “Introduction,” in Terrence Malick: Film and Philosophy, ed. Stuart Kendall and Thomas Dean Tucker (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), 4-5. Famously averse to publicity, Malick declines nearly all interviews, does not appear at awards ceremonies, and refuses to be photographed. As such, many of the details of his early biography are in dispute—including whether he was born in Waco, Texas or Ottawa, Illinois. It is known, however, that Malick studied philosophy at Harvard College—graduating summa cum laude in 1965—and won a Rhodes Scholarship to continue studying philosophy at Magdalen College, Oxford, though he never finished the program following a dispute with his advisor there. After a brief, reportedly unsuccessful stint teaching philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Malick enrolled at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. His first feature film, Badlands, was released in 1973.

A brief explanation of the different Christian uses of the terms “grace” and “nature” can be found in Leithart, Shining Glory, 36-38.

Thomas à Kempis, Imitation of Christ (Chicago: Henneberry Company, 1890), 215-216. Given the gendered elements of my argument, it is noteworthy that in Kempis's construction both nature and grace are given feminine pronouns.

N.B.—Among other self-imposed constraints, Lubezki limited himself to shooting The Tree of Life with only natural light.

This story of preferred access to the fruits of the New Deal and postwar state is thoroughly covered in Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Steve Gillon, Boomer Nation: The Largest and Richest Generation Ever, and How It Changed America (New York: Free Press, 2004), 4, 1.