“Patton's Flag, and Other Chi-Raq Disasters”

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

While a majority of mass media critics support Spike Lee’s film, Chi-Raq (2015), an ambitious adaptation of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (411 B.C.E.), set in present-day south Chicago, a vocal minority is particularly bitter about the film’s failures. In The New Yorker, Anthony Lane reports: “[I]t’s an awkward affair, stringing out its tearful scenes of mourning, and going wildly astray with its lurches into farce.”[1] In The Chicago Reader, Leor Galil summarizes: “Lee’s finished project isn’t strong enough to meet the mounting complaints against it—or say anything meaningful about the city’s murder rate that hasn’t been said better elsewhere.”[2]

Lee’s project from the start was a fundamentally impossible one, setting out to make both an “important” film about black-on-black gun violence and at the same time adapt Lysistrata, one of the funniest plays every written. Lee gets himself caught in a no man’s land in between making a serious social problem film and a sex farce.

For a quarter of a century, I have taught the political and media intertexts of Lysistrata, from the 1946 all-black New York theatrical production set amidst African-American soldiers returning from World War II only to discover the “Double V” had not ended Jim Crow, to the 1968 radical feminist film, Mai Zetterling’s Flikorna, starring Bibi Anderson from Ingmar Bergman’s troop.

My instinct is that Lee’s mistake was pulling his punches, retreating from Aristophanes’ Old Comedic project, making fun of a dire social moment, when Athens sat on the brink of collapse durning the end game of the Peloponnesian War. As an analogue, it would be a similarly mission critical error to try to film Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” (1729), but then decide against advocating for the on-screen eating of Irish babies.

While the critics are correct that Chi-Raq is an uneven mess, this also means that the film does have some sparkling moments. Lee’s choice of Samuel L. Jackson to play Dolmedes, the choragos, the leader of the chorus—while suffering from his by now grating hammy persona—does give the film charismatic gravitas at the moments when he precisely needs to infuse the sagging film with such energy.

As in his masterpiece, Do the Right Thing (1989), which also relies on a Greek chorus to comment on the tragic tale, Lee understands how to use the Greek theatrical conceit of public figures commenting on private, fictional drama.

Chi-Raq does well in its musical set pieces, matching the interruptive and contemplative function of such poetic moments in Aristophanes’ play. A particularly effective sequence uses split screen and cross cutting between the male and female chorus at the National Guard armory (a sensible stand-in for the Acropolis in Lysistrata). The male choral members sing and dance outside in their military skivvies, while inside, the striking women sing and dance across their cots.

But when Lee sacrifices the hilarity from Aristophanes, he dooms his film to having to resort to preaching. For example, the funniest moment in the play is when Myrhhine endlessly teases Kinesias under Lysistrata’s orders. She is to pretend to want to have sex with her husband, only to come up with excuse after excuse (the need for pillows, blankets, perfume) to endlessly torture him. His lament, “I’ve been up for days” is double-entendre at its best, augmented by the actor on the ancient stage having worn a ridiculous phallus to emphasize his torment.

The closest scene in Chi-Raq is when the Mayor of Chicago goes to have sex with his wife. They are role-playing: the mayor is a pharaoh, while his wife is Cleopatra. However, the scene falls flat; it ends far too quickly, without the deliberate comic build-up engineered brilliantly by Aristophanes.

The women take over the armory by using seduction to trick its commander, General King Kong (David Patrick Kelly). The scene is appropriately Aristophanic, relying on grotesque stereotypes: General Kong is a right-wing racist whose office features portraits of George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld, but not Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. The centerpiece of his office is a Southern cannon, "Whistling Dick," which he mounts while wearing his Confederate underwear in anticipation of having sex with one of Lysistrata's militants.

The appearance of General Kong sets up the denouement of Lee's Chi-raq. His name replicates the apocalyptic comedic nature of Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) in which a white Southern Air Force officer, Major King Kong (Slim Pickens) destroys humanity by dropping an atomic bomb on the Soviet Union. However, when we first meet Chi-raq's Kong, he has been promoted to general, wearing a four-star helmet, setting up the film's conclusion, a reconstruction of the opening of Patton (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1971).

At the end of all ancient Greek comedy, the chorus sings to celebrate the positive resolution of the conflict. In the case of Lysistrata, the women’s sex strike succeeds in ending the war. The men and women on the stage celebrate the end of hostilities by eating and drinking gluttonously, singing and dancing triumphantly. As the fiction ends, the characters leave the stage to jaunt off to finally have sex with each other. Lee completely abandons this ending, the very definition of comedy as regenerative fecundity, choosing instead to emphasize the serious nature of the unsolved social problem of black-on-black gang violence.

Instead, Lee produces a series of gestures that are intriguing, but ultimately do not function coherently enough within the Aristophanic conceit. Near the end, the chorus agrees that Chi-Raq (Nick Cannon) and his girlfriend Lysistrata (Teyonah Parris) must engage in a sexual competition.

The idea resonates with the history of radical African-American cinema, particularly Sweet Sweetback’s BaadAsssss song (Melvin Van Peebles, 1971), in which an expert male libidinal performer challenges the leader of a female biker gang to a similar sex battle. However, the scene in Chi-Raq serves no apparent narrative function, as the rival gang leader, Cyclops (Wesley Snipes) arrives independent of the sex performance in order to end the gang warfare.

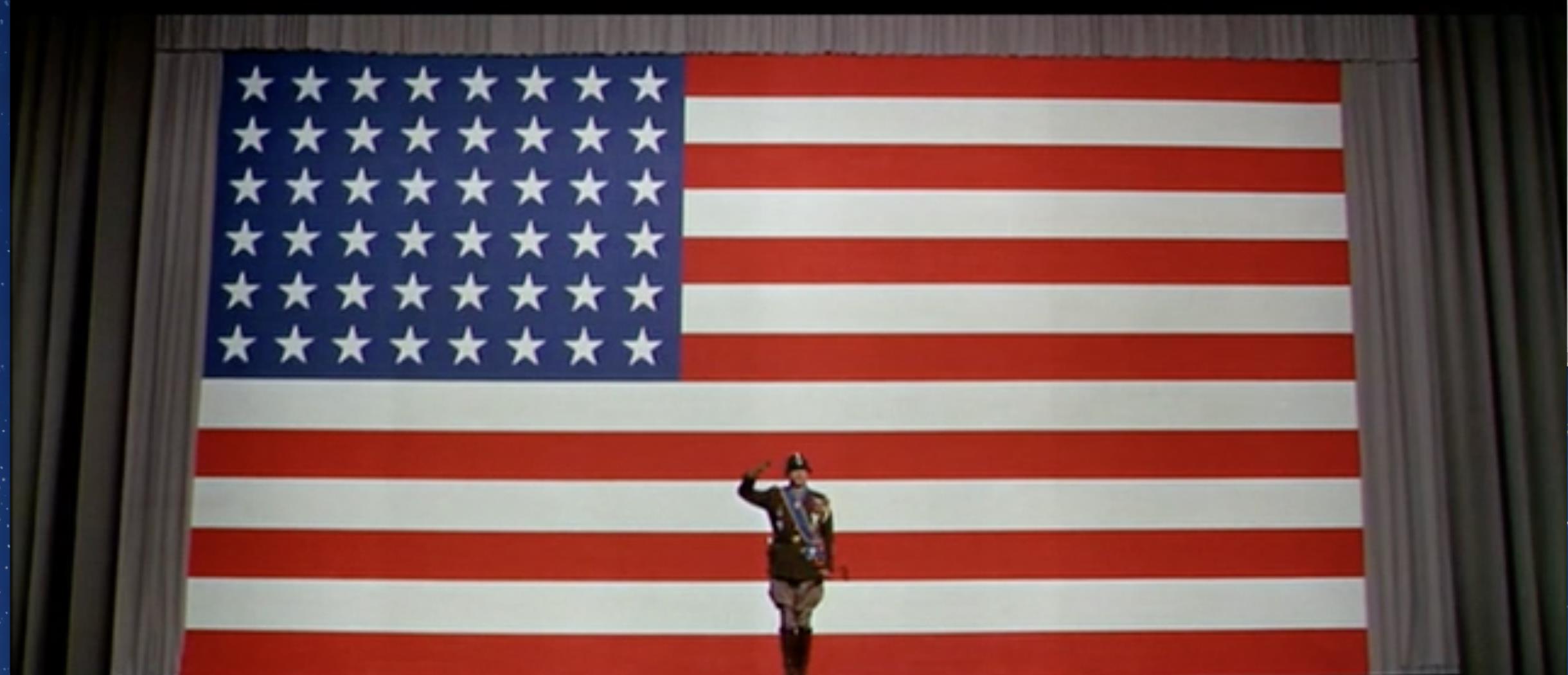

Chi-Raq ends with a different film parody. The astute historian and cultural critic Dolmedes stands in front of a massive United States flag to argue, “The only real security is love, y’all.”

The text superimposed in front of Dolmedes recalls the Brechtian separation of the elements in the films of Van Peebles, wherein American racism is interrogated by the disparity between sound, text, and image. For example, in Watermelon Man (1970), Jeff (Godfrey Cambridge) is fired from his job as an insurance salesman when he falls asleep under a tanning lamp and turns black overnight. In a spectacular musical number, "Love, That's America," the superimposed titles spout purportedly uplifting, racist platitudes while the images capture Jeff's descent: the only job he can find after getting fired is at the dump.

Given Jackson’s over-the-top theatrical performance and the ridiculously large patriotic backdrop, Chi-raq's ending echoes the famous opening of Patton in which the general (George C. Scott) delivers a bellicose opening monologue to the audience, his troops about to go into battle against the Nazis: “When you stick your hand into a pile of goo that used to be your best friends’ face, you’ll know what to do.” By placing Dolmedes’ lesson about the importance of love at the opposite end of his film, inverting the general’s justification for violence, Spike Lee finally delivers the full force of Aristophanic satire.

However, the joke comes too little, too late. Chi-raq instead returns to preaching: a title card implores us to “Wake Up,” as the American flag is replaced by four red stars framed by two pale blue stripes, poet Wallace Rice’s 1917 design for the flag of the City of Chicago.

Coupled with the poster for Chi-Raq, which layers red, black, and green, the colors of the pan-African flag, we are left with a swirl of reductive banners instead of comedy, draining the film of its intellectual force. Chi-Raq’s emotional appeals bash us in an unending tide of emblems, which is not to say that the film’s fact-based rage at the unacceptable murder rate in Chicago is misplaced.

Early on, Lee commits his film to Aristophanes’ method, so that by the end, the abandonment of comedy for other forms of political critique results in mere confusion. Aristophanes saw no need to retreat from comedy and resort to clichéd political messaging because he invented the most radical response possible to a horrifyingly violent and cruel world. When the Spartans came marching into Athens to destroy civilization, the poet’s response was not to lament, but to laugh. Such derisive laughter is one of the greatest gifts bequeathed to us by the ancient world. If only Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq could have found the artistic courage to commit to its power.

Author Biography

Walter Metz is a Professor in the Department of Cinema and Photography at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, where he teaches film, television, and literary history, theory, and criticism. He is the author of three books: Engaging Film Criticism: Film History and Contemporary American Cinema (2004), Bewitched (2007), and Gilligan's Island (2012).

Notes

Lane, Anthony. "Hard Bargains." The New Yorker. December 6, 2015.

Galil, Leor. "Spike Lee takes on Chicago gun violence, but where are the victims?" The Chicago Reader. November 25, 2015.

This production still from the 1946 production of Lysistrata is taken from Salamishah Tillet's essay, "In Spike Lee's 'Chi-Raq,' It's Women vs. Men, With a Vengeance," published on December 3, 2015 in The New York Times.