Disarming Montage

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This essay examines the work of two major contemporary artists—Hito Steyerl and Harun Farocki—to suggest a novel framework for considering cinematic politics in general, and the politics of montage in particular, in the contemporary moment. Both artists are deeply critical of the ways in which montage, across the history of cinema, has been associated with a range of violent and militaristic images. Discussing the work of Steyerl and Farocki along these lines, this essay seeks to displace the historical analogy between cinema and war by foregrounding the ways in which cinematic politics may be grounded in a spatial and geographic language. Grounding these claims is an examination of two particular works: On Construction of Griffith’s Films (Harun Farocki, 2006) and Abstract (Hito Steyerl, 2012), with the second part of this essay reserved for a close reading of the latter.

Speaking to an audience at the 2014 Flaherty Film Seminar, the filmmaker Hito Steyerl suggested an urgent need for new ways of thinking cinematic politics. “A different metaphor has to be found,” she asserted, “for the old dialectical model, first of all of montage, but also of shooting against one another.”[1] These observations underscore a core tenet of Steyerl’s praxis: that the production and circulation of contemporary media demand novel ways of thinking, of being, and of resisting. In this instance, under interrogation is the avant-gardist ideology of counter-cinema, the legacy of which persists in the seemingly benign dichotomization of “shot/countershot.” Suggesting two images locked in combat, the formulation of shot/countershot cannot help but conscript cinema’s plans to war.

More than any material and formal fact of either cinema or war, this is primarily a discursive question: of how scholars and practitioners have historically envisioned cinematic politics through a dualist—or as it were duelist—framework. Even as the technologies of cinema and war have fundamentally changed, this metaphor persists largely intact, its full implications uninterrogated. Today’s advanced and thoroughly global financial and military systems are sufficiently comprehensive, delocalized, and slippery to bedevil any deterministically oppositional view of politics, cinematic or otherwise. Perhaps what truly vexes the language of shot/countershot is less that it is grounded in a logic of conflict per se than its basic incompatibility with how images and deadly projectiles circulate today. As Paul Virilio has noted, unprecedented advances in the “technological vehicle” fundamentally shifted the parameters of war. With the advent of “the supersonic vector (airplane, rocket, airwaves)” came the disappearance of “the world as a field, as distance, as matter.”[2] Speed thus emerges as the sine qua non of contemporary warfare, which in turn spells a radical narrowing of space and the ascendance of time as the zone of conflict. Virilio writes,

If, as Lenin claimed, “strategy means choosing which points we apply force to,” we must admit that these “points,” today, are no longer geostrategic strongpoints, since from any given spot we can now reach any other, no matter where it may be. . . geographic localization seems to have definitively lost its strategic value and, inversely, that this same value is attributed to the delocalization of the vector, of vector in permanent movement...All that counts is the speed of the moving body and the undetectability of its path.[3]

Any paradigm figuring discretely opposed forces locked in battle, because it necessarily assumes a stable field of action, would seem to have little bearing on today’s wide-ranging, de-centered, and largely instantaneous and invisible movement of deadly vectors. But to elucidate how cinema figures into these questions, I turn to another figure who, like Steyerl and Virilio, has also interrogated the relationship between cinema and war: Harun Farocki.

With reference to his Eye/Machine (2001-2003) series, Farocki once remarked, “The key to ‘intelligent weapons’ is image processing. Images of the terrain it is to traverse are stored in a rocket. During its flight, it photographs the terrain below and compares the two images, the goal image and the actual image. The idea of working with two image tracks to illustrate the process of comparing performed by software is an obvious corollary.”[4] As Farocki attests, the operations underlying this fatal interplay between “image” and “weapon” are grounded in comparison and simultaneity rather than opposition, the suggestion being that traditional montage lacks a basic explanatory power before such processes, since in traditional montage shots appear in succession rather than simultaneously, as in the “double projection” scenario of the smart bomb. What should be clear at this point is that the language we have traditionally used to account for the politics of montage no longer has the same capacity for clarifying the workings of power, and has serious shortcomings as a model for resisting it.

This essay examines the efforts of both Steyerl and Farocki to rethink the association of cinema and war precisely on such grounds. They do so at once to disclose the material as well as metaphorical points at which cinema and war intersect, while displacing the old avant-gardist ideology of counter-cinema with one that acknowledges the complexity and fundamental irrationality of the contemporary circulation of power. In doing so, they trade in a language of montage grounded in conflict, force, and speed with one based on comparison, excavation, and simultaneity. Ultimately, the aim of this essay is less to refute the film-war analogy than to throw it into sharper relief, measuring its liabilities and its assets against the complex and interwoven processes of war, automation, and image production in the contemporary moment, while suggesting an alternative roadmap for regarding cinema’s capacity to effect political change. In the final instance, Steyerl’s aim in interrogating the dialectical model of montage isn’t to repudiate oppositional aesthetics tout court, but to inquire into our manner of speaking about images, what we want from them, and how these ways of speaking and desiring correspond to the reality of how images and power circulate in and shape the world. A basic assumption of this essay is that no necessary or fundamental correlation inheres between cinema and war. Cinema isn’t bound (ontologically or otherwise) to violence any more than it is to peace, but exists on an analogical continuum, with “harder” and “softer” associations emerging depending on material, discursive, formal, cultural, and historical conditions. Cinema’s points of affinity or kinship are above all contingent upon the subjects that engage it and the world in which it exists.

I begin by outlining a brief history of the film-war analogy as it subtended the discourse of the cinematic avant-garde from Eisenstein to Godard. I then move into a discussion of Farocki’s practice before, in the second part of the essay, offering a close reading of Steyerl’s dual-channel video Abstract (2012) to further advance the ideas and claims raised in the preceding discussion.

*

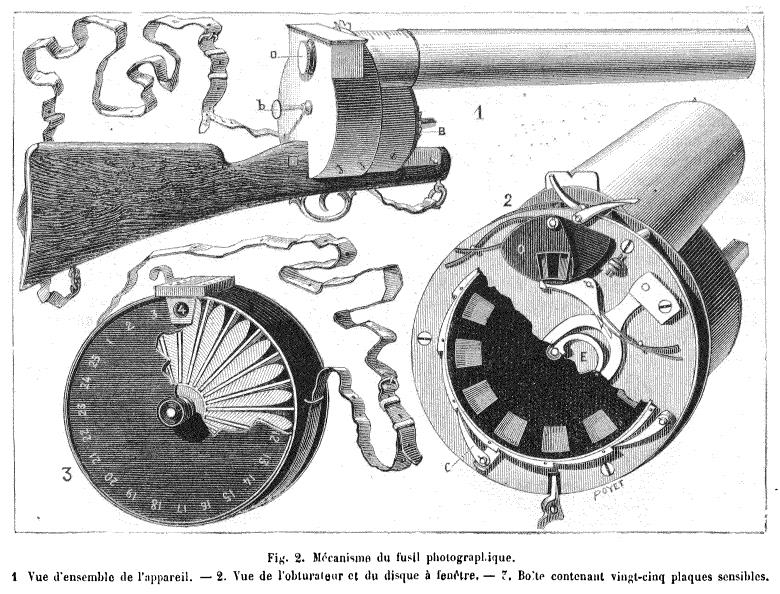

The abiding power of the film-war analogy derives in part from the fact that it is as old as the medium itself.[5] In the late nineteenth century, Étienne-Jules Marey conceived the “photographic rifle” (fusil photographique) to showcase his chronophotographic method.

Suggesting a kinship between the acts of aiming a firearm and framing a shot, this consolidation of camera and gun, for many commentators, betrays an armamentary logic underlying the project of cinematic movement. “With the chronophotographic gun,” media theorist Friedrich Kittler would later write, “mechanized death was perfected: its transmission coincided with its storage.”[6] Kittler’s canny but ultimately tenuous claim here relies on finding in the historical imbrication of proto-cinematic technology and firearms a structural complicity between cinema and martial violence, such that the former becomes ontologically conditioned by the latter.

Of those who would enlist cinema in the designs of war, Sergei Eisenstein was among the earliest and most persuasive. Conceptualizing that union through the framework of dialectics, Eisenstein wrote in 1929 that “montage”—always his chosen weapon—“is conflict.”[7] While his emphasis on conflict didn’t always amount to an outright valorization of war, the two were certainly linked in his thinking. Recalling a battle sequence from his 1938 film Alexander Nevsky, Eisenstein notes that before the battle even begins, “This clashing of the two foes is first shown as a clash of shots.... this clash of the plastic elements that characterize the antagonists for us.”[8] The “battle” in question, which precedes any depiction of war because it occurs at the level of filmic signifiers, conditioned Eisenstein’s politics of montage.

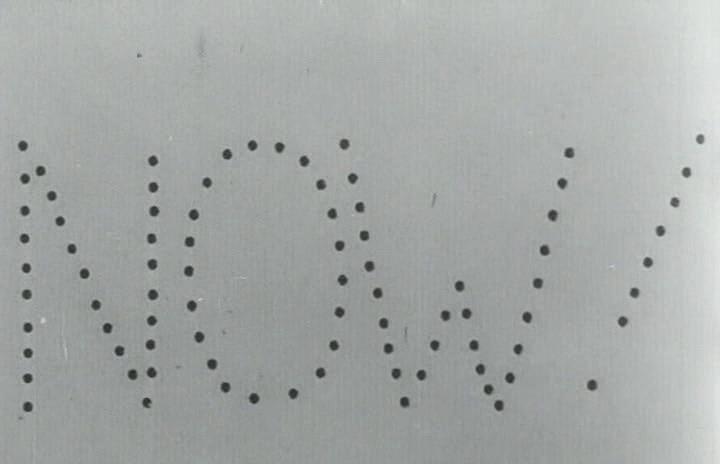

Eisenstein’s model would be repurposed by radical practitioners around the globe during the second half of the twentieth century. One of the great torchbearers of this cinematic ideology was the Cuban filmmaker Santiago Álvarez, whose rapid-fire montage film, Now (1965), reinforced its militant ethos with a stop-motion animation of the film’s title at its conclusion, drawn with bullet-sized incisions on a paper canvas.

The deafening sound of a machine gun serves only to secure the analogy: cinema must be weaponized; filmmakers and spectators, take up arms. Having once famously declared, “Give me two photographs, a Moviola and some music and I’ll make you a film,” Álvarez located cinema’s political valence not in solitary images but in montage, where the cut itself becomes a space of ballistic propulsion capable of collapsing walls and breaking chains.[9] Elsewhere, in the United States, there could be no mistake as to the militant ethos of the Newsreel Collective, whose logo famously consisted of rapidly flickering text accompanied by the sound of a machine gun. The Argentinian filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Gentino further seized upon the film-war analogy in their influential essay “Towards a Third Cinema.” Their filmmaker figure bore an explicit resemblance to the revolutionary guerrillero, whose camera was the “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons,” his projector, “a gun that can shoot 24 frames per second.”[10] An unspoken but decisive term in this characterization of cinema’s revolutionary mechanics is montage, which presides over the passage from camera, to projector, to gun. Like Álvarez, Solanas and Gentino located cinema’s capacity for mobilizing revolutionary bodies not in the recording of images, but in their grouping: their retooling as munitions by way of the cut.

Second only to Eisenstein’s rigorous martialing of cinema’s revolutionary mechanics were the efforts of Jean-Luc Godard, who would also emerge as one of the severest inquisitors of that very discourse. In a cameo appearance in Godard’s 1965 film Pierrot le fou, the American director Samuel Fuller parodied the revolutionary ethos of the era’s leftist cinema with the line, “Film is like a battleground.” Not long after this, Godard would reinvent himself as a militant filmmaker for the internationalist cause in the late 1960s when he formed the Dziga Vertov Group (DVG) with Jean-Pierre Gorin. Jusqu’à la Victoire (Until Victory) was to be one of the group’s films. Conceived as a cinematic study of the Palestinian Revolution, Jusqu’à la victoire would comprise footage shot in refugee camps and Fedayeen training facilities, and was intended to mobilize international support for the cause of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. In 1970, Godard laid out the group’s intentions for the project by way of an editing metaphor: “Each combination of images and sounds are moments of relations between forces, and our task consists of directing these forces against those of the common enemy: imperialism.”[11] Then, in September, King Hussein ordered the destruction of the Fedayeen network in Jordan, resulting in the death of thousands of Palestinian guerrillas, some of whom had appeared in the footage collected for Jusqu’à la victoire. In light of this catastrophe, Godard balked at the prospect of deploying images of vanquished Fedayeen in a film proclaiming victory for Palestine. Jusqu’à la Victoire was consequently abandoned and DVG dissolved.

Years later, Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville would revisit the Middle East footage, resulting in a film called Ici et ailleurs (1976). Approaching the Palestinian footage reflexively, Ici et ailleurs effects an exhaustive autocritique doubling as a repudiation of the French Left. Absent here are the triumphalist slogans of international leftist solidarity, along with any clear sense of how cinema could be deployed to such ends. Indeed, throughout the film, the practice of montage is likened to a kind of false resolution of tension. “Death is represented in this film by a flow of images,” Godard remarks pensively over footage of military training exercises intercut (and interrupted) by images of vanquished Fedayeen in the aftermath of the Black September massacre, implying an analogy between the additive valence of montage and martial violence. In an explicit reversal of Godard’s claim in 1970 that montage must be weaponized toward revolutionary ends, here a sequence of images figures as so much chatter that drowns out silence and negates the crisis of death. The consequences of this are powerfully borne out in a sequence where the filmmakers, heard in voiceover, comment on footage Godard and Gorin had captured of a group of Fedayeen soldiers discoursing on how to reoccupy an Israeli-held river embankment. “This is why we shouldn’t gather at one point,” they say, “These passages shouldn’t be individual, but made so that two or three of our group could cross the river at once.” Godard responds to this scenario melancholically, “What is really tragic is that they are here talking about their own death. But nobody said that.” To this, Miéville adds, “No, because it was up to you to say it and what is tragic is that you didn’t.” An extended period of silence follows, where neither the filmmakers nor the Fedayeen speak. At last, Godard admits, “It is true that even to silence, we never listened in silence.”

There is a line in Ici et ailleurs that aptly distills the film’s tenor of post-revolutionary disenchantment:“Time,” Godard says, “has replaced space, speaks for it, or rather, space has inscribed itself on film in another form, which is not a whole anymore, but a sum of translations, a sum of feelings which are forwarded.” In an intriguing prelude to Virilio’s claims a mere year later with the publication of Speed and Politics, Godard and Miéville describe a general triumph of time over space and its consequences on politics. These insights, in turn, ground the film’s critique of the ideology of cinematic production as emancipation, and by extension of montage as a dialectical staging of images for countering power.[12] For Godard and Miéville, that model of montage is too similar to the spectacle of televisual flow: a “vague and complicated system,” as they call it, “where the whole world enters and leaves at each moment.” At one point, Godard even suggests that global capitalism “builds its entire wealth” on the idea that the whole world may be captured in a single image. Godard and Miéville’s response to this dilemma consists in their repurposing of the cut as a space of silence and of possibility: one meant to actively repel ideology and intervene in the flow of images. The cut, which is frequently made visible in Ici et ailleurs either in the form of black leader or even graphically through the word et rendered in three-dimensional blocks, becomes a means of interrupting spectacle, becomes a “place” within which the filmmakers relinquish their claim over others, over images, and turn down the noise to fall on the side of listening. What these cuts forbid is an underlying logic of montage which assumes a common discourse, a shared politics, whether to unite here and elsewhere or delineate friend from foe. The cinematic interstice thus becomes not only a figure of the fragmentation of space (“time as replaced space... which is not whole anymore”), but of a political action that operates not as force but articulates a “sum of feelings,” an affective topography for new associations and insights.

That a cut separates us from the grand political struggles of history is a premise tempering the practice of Steyerl and Farocki. At the same time, the work of both filmmakers is shot through by a tireless and patient movement of critique: one which follows from but also extends Godard and Miéville’s qualification of dialectical montage. At first glance, Farocki’s early short film Inextinguishable Fire (1969) seems to operate that oppositional rhetoric which prevailed in much of the leftist cinema of the time. In a central scene, a self-inflicted cigarette burn on the artist’s arm serves to illustrate the devastating effects of napalm on the North Vietnamese: a metaphor which, as Thomas Elsaesser suggests, resonates for its total inadequacy as such.[13] That inadequacy or poverty of Farocki’s gesture is critical, because it explicitly does not seek to collapse the burned bodies of North Vietnamese with the filmmaker’s own, but posits itself as a gap.

This is an act of montage founded upon comparison—a comparison with a difference—rather than strict opposition or equation. As Farocki himself notes, the burn is a “point of relation to the actual world.”[14] This is true to the extent that this burning, precisely because of its inadequacy in the face of its referent, effects an opening rather than closure. More recently, in the dual-channel piece, I Thought I Was Seeing Convicts (2000), Farocki appropriates CCTV footage from a California prison. At one point, a guard fatally shoots a convict during a prison brawl. “The pictures are silent,” Farocki writes of these images: “The trail of gun smoke drifts across the picture. The camera and the gun are right next to each other.”[15]

That the camera is “right next to” the gun—that they are practically synonymous—impels us to look further than the individual camera, to go beyond the individual shot. This is to say that just one camera, just one totalizing shot, can be as deadly as a gun. To undermine this fatal silence, one must have many cameras, many shots, since no image is fatal where it is among others. This is montage as disarmament.

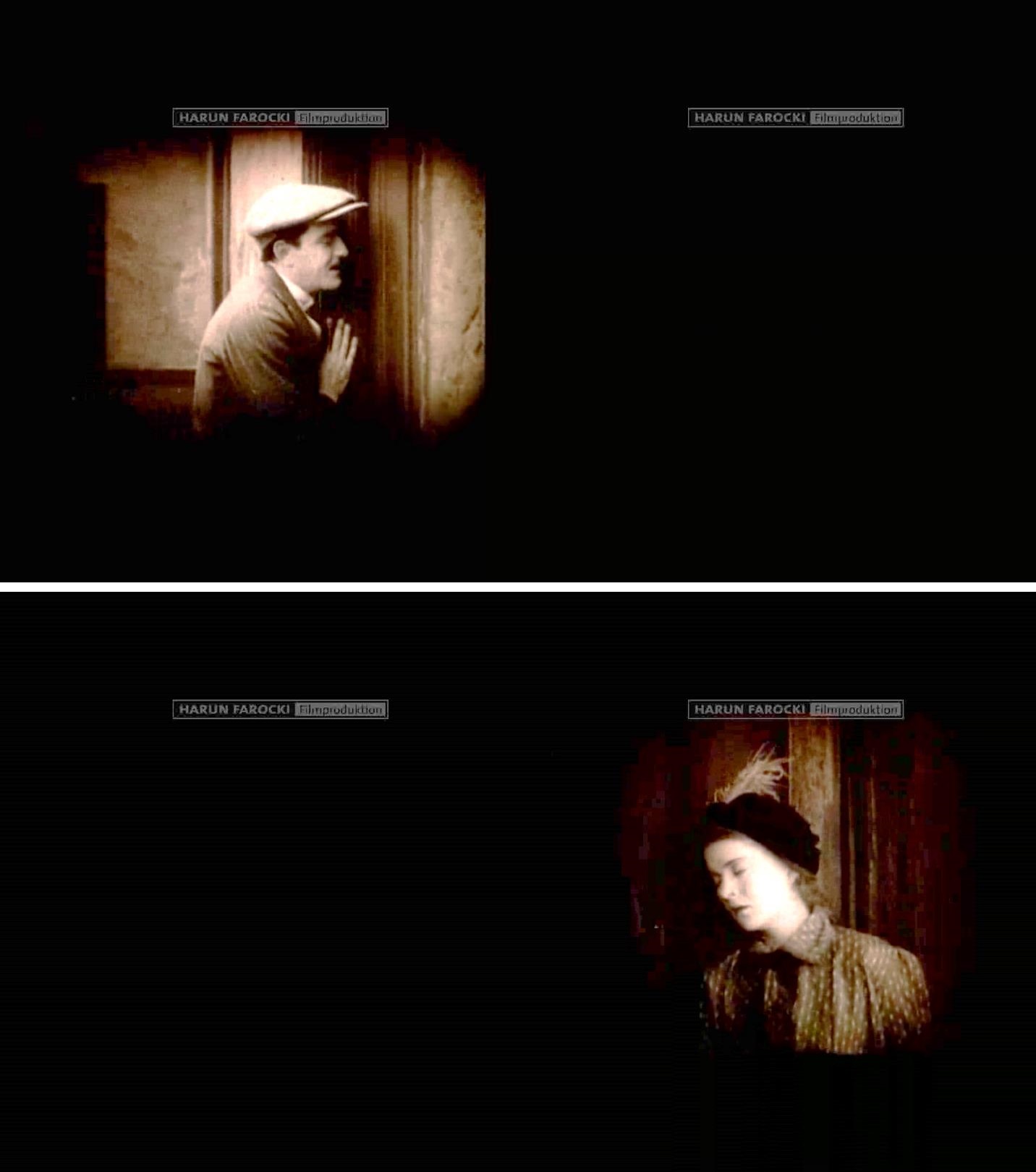

The term “soft montage,” coined by Farocki and Kaja Silverman with reference to Godard’s Numéro deux (1975), characterizes editing at its most open and porous. As opposed to the traditional filmic cut where, as Silverman observes, “one image comes after another, and implicitly negates everything which it isn’t,” what animates soft montage is, according to Farocki, “a general relatedness, rather than a strict opposition or equation,” for it “does not predetermine how two images are connected.”[16] Such a “general relatedness” could perhaps characterize the effect of Farocki’s act in Inextinguishable Fire as it could the analogy put forth in Convicts between a camera and a gun. But this soft touch animates Farocki’s work on yet another level, and this can be gleaned in another of his dual-channel works, On Construction of Griffith’s Films (2006), which explores the construction of space via cinematic editing in two films by D.W. Griffith, The Lonedale Operator (1911) and Intolerance (1916). A scene from the latter that especially interests Farocki depicts a courtship between a man and woman separated by a door. Early in the scene, Griffith depicts the couple in a two shot as they dwell in a corridor. Soon after the man invites himself in, the woman darts inside, closing the door behind her. From this point onward, until the end of the scene when they kiss, Griffith shows the man and the woman in single shots, outside and inside the apartment respectively. In his experiment, Farocki further isolates the two subjects by disrupting the unity of the cinematic frame itself, displacing their respective shots onto discrete channels and separate monitors.

Elsewhere, Farocki has distinguished between two modes of image relations: “succession” and “simultaneity.”[17] Whereas in Griffith’s traditionally cinematic sequence one shot takes the place of another within the frame (i.e., succession), in Farocki’s dissected version the digital equivalent of black film leader marks a shot’s absence (i.e., simultaneity). Yet one shot does not replace another in the sense of substituting for it within the frame, but rather flickers in and out of existence on its own screen. In a way that feels intrinsically more dialogical than the sort of montage occurring within the space of a single frame, the absence of a given shot registers—that is, it remains—in this ostensibly negative space.

While the premise of On Construction is relatively simple, it is remarkably effective in elucidating the expanded function of montage at multiple spatial registers. The movement holding these shots and bodies together and apart registers spatially as well as temporally, since fully regarding the additive and subtractive processes of montage here requires that one physically orient oneself to behold one screen or another. Precisely the same effect could not be achieved, say, using a traditional single-channel split-screen technique, since the distance/proximity between shots here is inextricable from the space between screens, and by extension, the space occupied by the viewer. At times throughout the piece, Farocki fills the “empty” shots with critical intertitles that navigate and name these spaces. In doing so, he writes an architectonic history of film editing: “A door stands between the subjects and between the shots as a connection and separation. As if again to deduce—what this is: montage. Cinematography erects imaginary walls, opens and closes imaginary doors.”[18] The first sentence here is especially pertinent, for the word “door” may be substituted for the word “cut.” Like a door, the interval between shots mediates space deixis. Cinematography and montage, doors and walls—such devices not only reorder and represent space but comprise space.

The mere fact that Farocki would characterize montage in such terms attests to the distance between his project and the disenchanted, “post-spatial” politics of Ici et ailleurs. In other words, On Construction is indicative of a larger tendency in Farocki’s work to not take the evacuation of space for granted. And yet, like so many technologies, doors have undergone significant changes in the course of the last century. As Bernhard Siegert points out, the traditional symbolic door has today been replaced by numerous automatic devices whose opening and closing are mediated not by physical contact, but instead, by an “invisible power.”[19] Beginning with the introduction of the revolving door into public spaces to the ever-increasing prevalence of automatic sliding doors, fundamental shifts have been occurring at the level of everyday experience. What might be the endgame of such a cybernetic operationalization of bodies if not a kind of disappearance of space altogether? Indeed, as Siegert attests, cybernetic doors mean that “the basic distinction of inside and outside has been replaced by the distinction between current/no current, on/off,” and as a consequence, “the place of the law is replaced by a short circuit between the imaginary and the real.”[20] Adrift in a cybernetic field, one cannot know whether a door leads to fantasy or oblivion. Likewise, as Farocki himself contends, “electronic control technology” has had a “deterritorializing effect” on lived experience, as “locations become less specific.”[21] And as early as 1987, Virilio suggested that the interfacing of screens with computer terminals and telecommunication technology already meant that “architectonic elements begin to drift and float in an electronic ether, devoid of spatial dimensions” so that the “distinctions of here and there no longer mean anything.”[22] Not unlike Godard’s “uninterrupted chain of images,” here, space is rendered as a chain-work of undifferentiated locations, or as Virilio characterizes the dream of the “war model,” an “artificial topological universe: the direct encounter of every surface on the globe.”[23]

I began this essay with Steyerl’s claim that an alternative metaphor to that of opposition and conflict must be found for montage, since such a conception is not sustainable “under the present technological conditions.”[24] I have already suggested, through Virilio and others, that a fundamental problem has to do with a radical compression of space. This is to say that images have forfeited their coordinating function, are no longer quite able to situate their beholders decisively in the world. As Wendy Chun has noted, “If you believe that your communications are private, it is because software corporations, as they relentlessly code and circulate you, tell you that you are behind, and not in front of, the window.”[25] Curiously, as in Siegert’s analysis, Chun poses this problem through an architectural metaphor. Digital technologies collapse spatial coordinates by way of substitute thresholds that obscure rather than clarify the underlying operations of the hardware or software. The poverty of the digital interface or operating system as a window is that it precisely confounds the relationship between inside and outside, capturing its user in an all-encompassing interiority. Considering such problems, Steyerl’s call for a new conception of montage appears less as an appeal to the egalitarian function of contemporary imaging technologies than as a clarification of their suturing operations. Here, we need only consider the means by which most images today are produced: on cameras embedded within smartphones. The crucial part of this story has less to do with the convergence of telecommunication and imaging technologies, however, than with the spatial situation of the smartphone camera: namely, the front-facing lens, which marked the beginning of the contemporary selfie.[26] By allowing users to take pictures in either direction without physically moving the device, the front-facing smartphone camera altered the very structure of photography, blurring the distinction between what is in front of and behind the camera, between shooter/target, onscreen/off-screen. Thus, as Steyerl asserts, “off-screen” has vanished—it is “nowhere,” and yet, somehow, it is “everywhere” at the same time.[27] With the advent of the smartphone camera’s doubled lens, and the attendant undecidability between shooter and target structuring its visual field, offscreen has become an endangered species, for the image’s “outside” is subject to the interchangeability of a mere switch. Just as the mass implementation of automatically revolving and sliding passages signals a forfeiture of the door’s symbolic function (inside/outside) for a cybernetic one (on/off), so too does the doubling of the camera bespeak the radical reversibility of contemporary images. It is as if we find ourselves in some ultimate stage of expanded cinema, where all the world’s a shot.

Abstract: A Close Reading

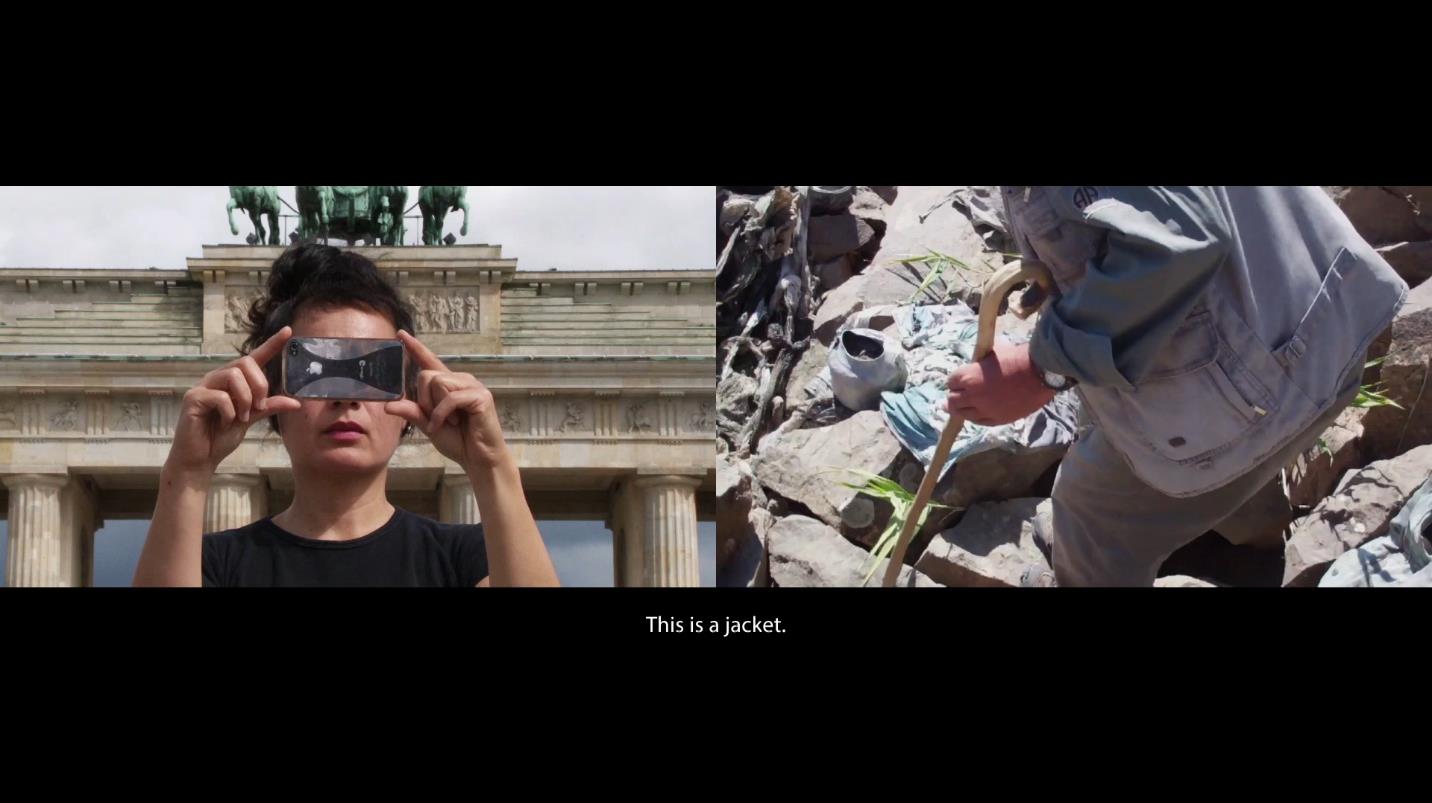

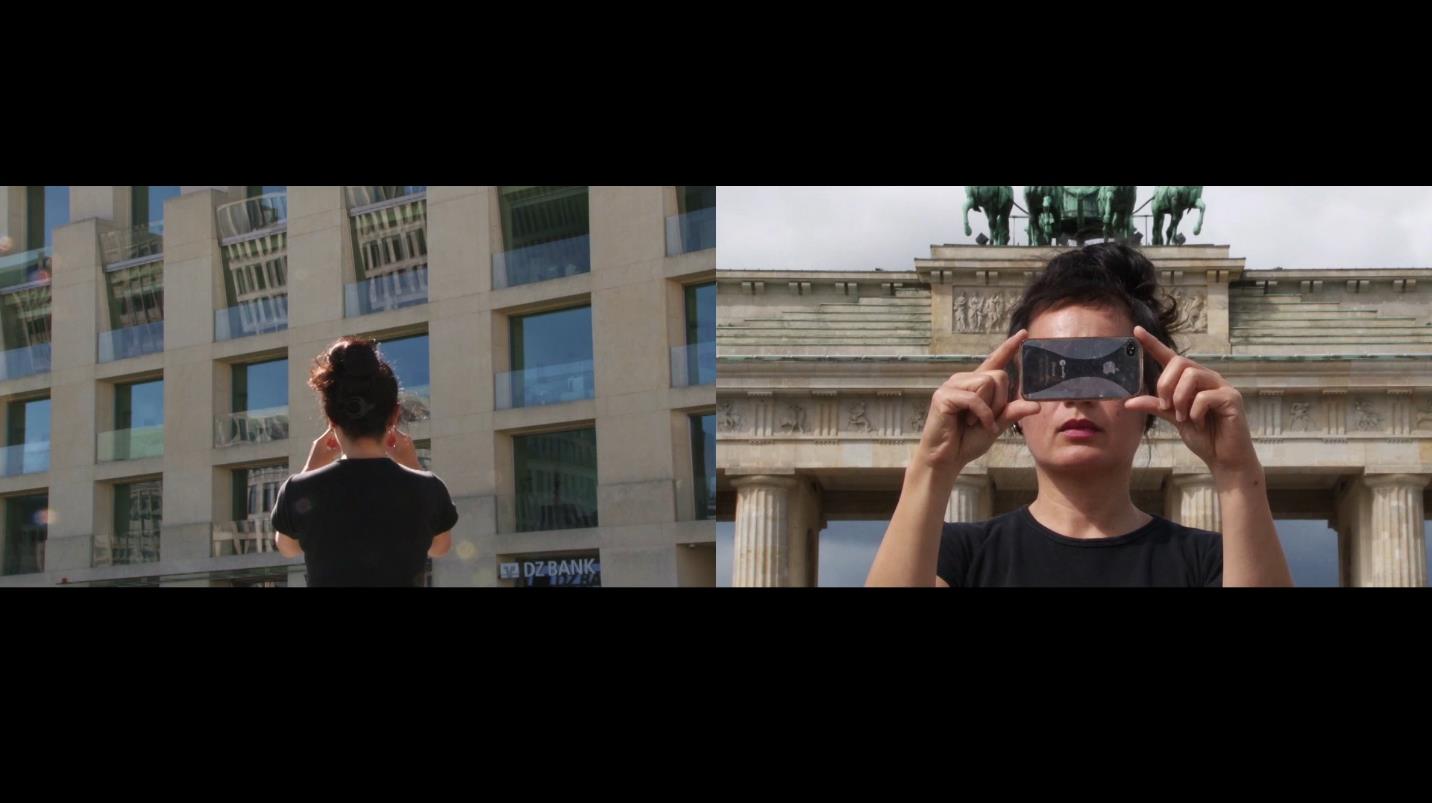

Inspired in part by Farocki’s On Construction, Abstract is a dual-channel work that envisages editing as a spatial phenomenon. At the same time, however, Abstract attempts to articulate the consequences and uses of such a spatial conception of montage for contemporary politics. Like November (Hito Steyerl, 2004), Abstract concerns the life and death of German-borne activist Andrea Wolf. Once a close friend of the artist, Wolf enlisted in the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (or PKK)—the militant left-wing organization long deemed a terrorist group by the Turkish state—and in 1998 was killed along with nearly forty other militants in a raid on a PKK encampment by Turkish Armed Forces. Much of Abstract features an interview Steyerl conducted with a Kurdish man who witnessed the event. Throughout, the viewer is shuttled between the site of Wolf’s death in southeastern Turkey and a crowded square in Berlin as the many points of distance and proximity between these places are gradually revealed. The process that ensues is thus to be distinguished from the dialectical language of montage espoused by Eisenstein, for what Steyerl assumes from the outset is something resembling a spatial totality, disjunctive and paradoxical as it may ultimately prove to be.

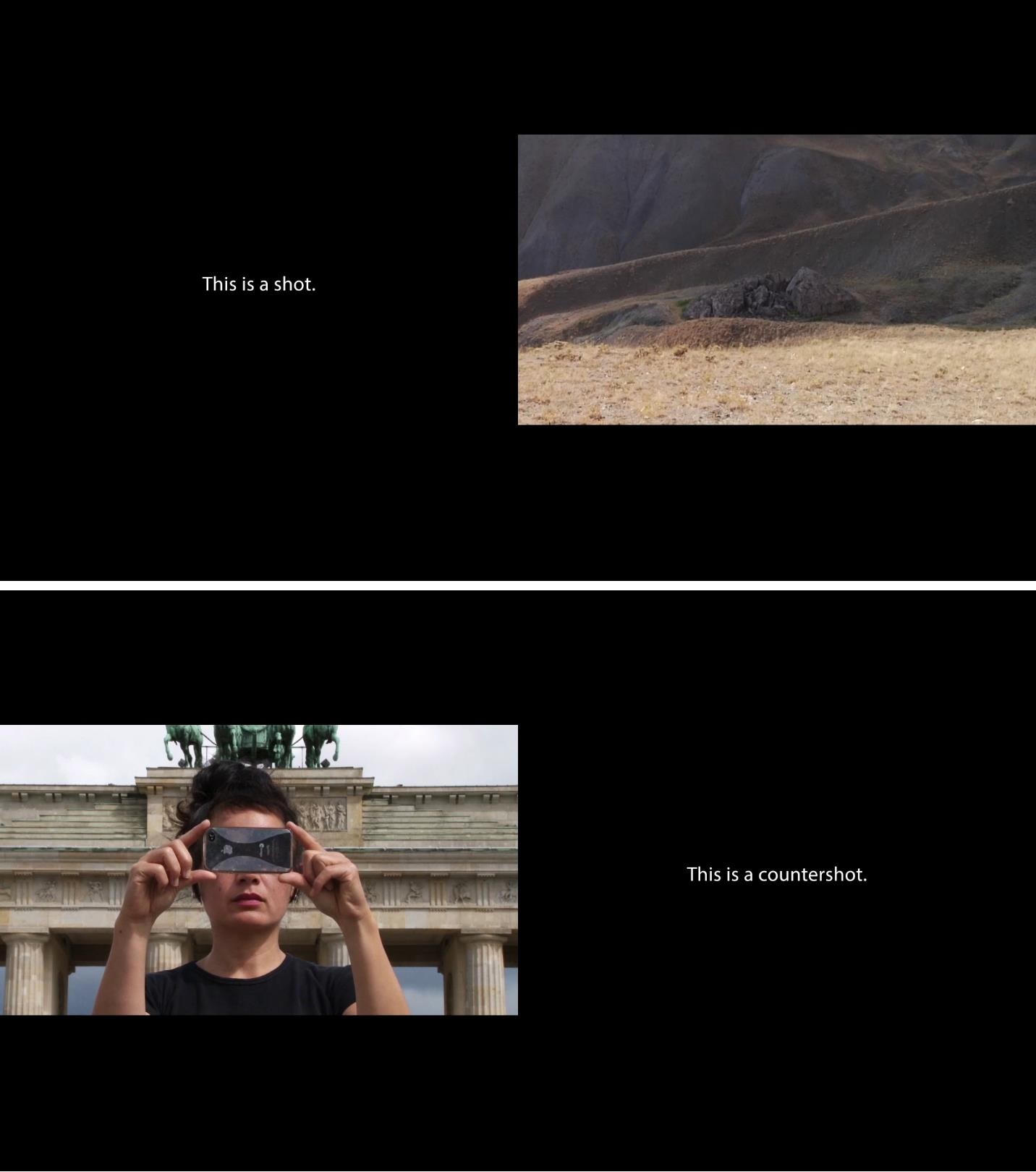

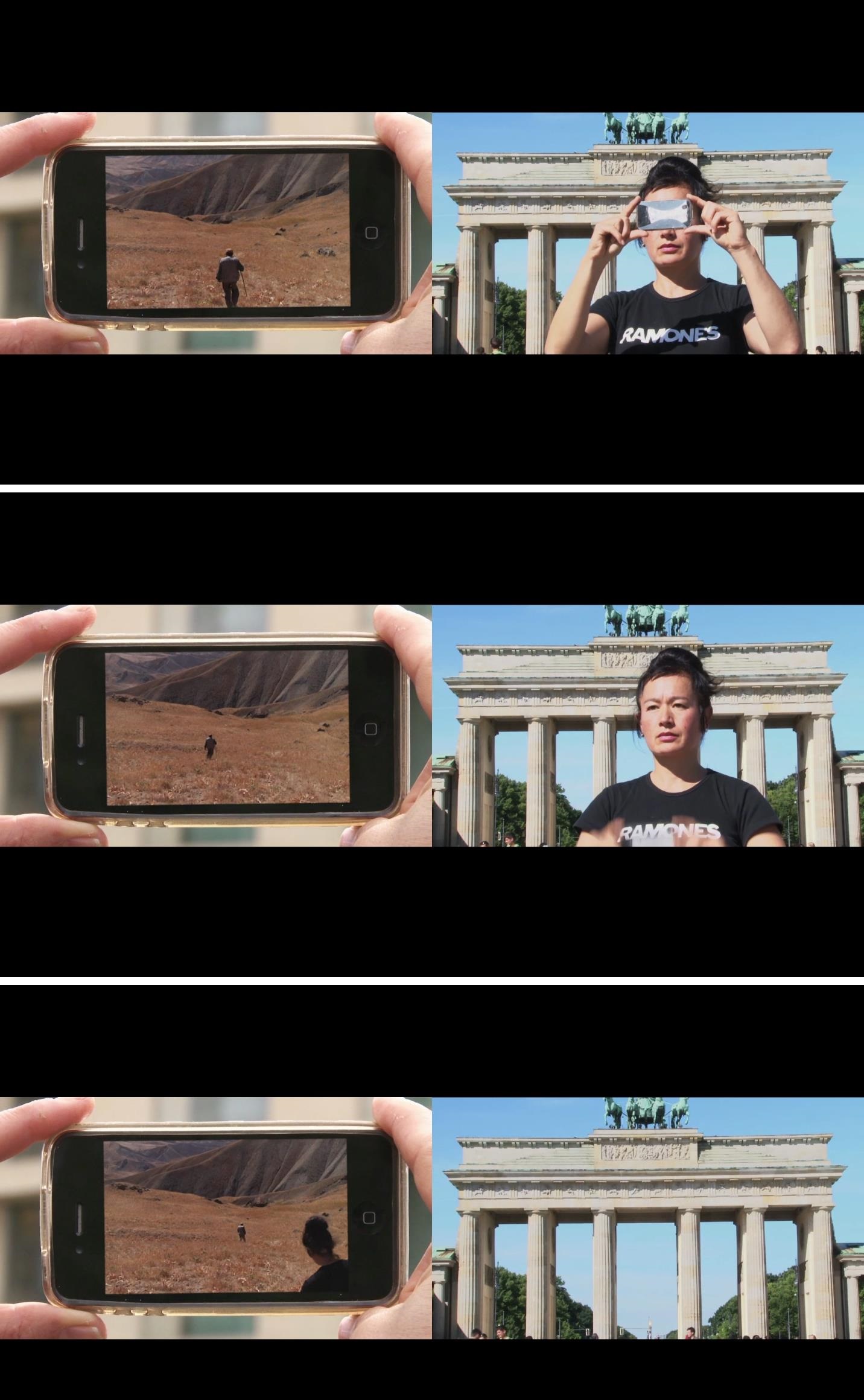

At the beginning of Abstract, a sentence appears on the left screen: “This is a shot.” Even as the statement prompts anticipation for the shot in question, we are also aware of the digital black leader that fills the screen on the right, which echoes the interstitial space of both Ici et ailleurs and On Construction. The difference here is that a black frame is itself presented as a shot as much as the shot’s other. Thus, in the first few seconds of Abstract, the deictic “this” and the signified of “shot” are subjected to a turbulence and stretched across the expanse of two screens. But as soon as this plasticity of indexicality is established, something conventionally recognizable as a “shot” springs into existence on the right-hand screen. Its frame betrays a faint motion as it floats, hazy, amid a rocky landscape in Kurdistan. We are plunged once more into darkness and remain suspended there until another sentence appears in place of the previous image: “This is a countershot.” A new shot emerges, this time on the left-hand screen.

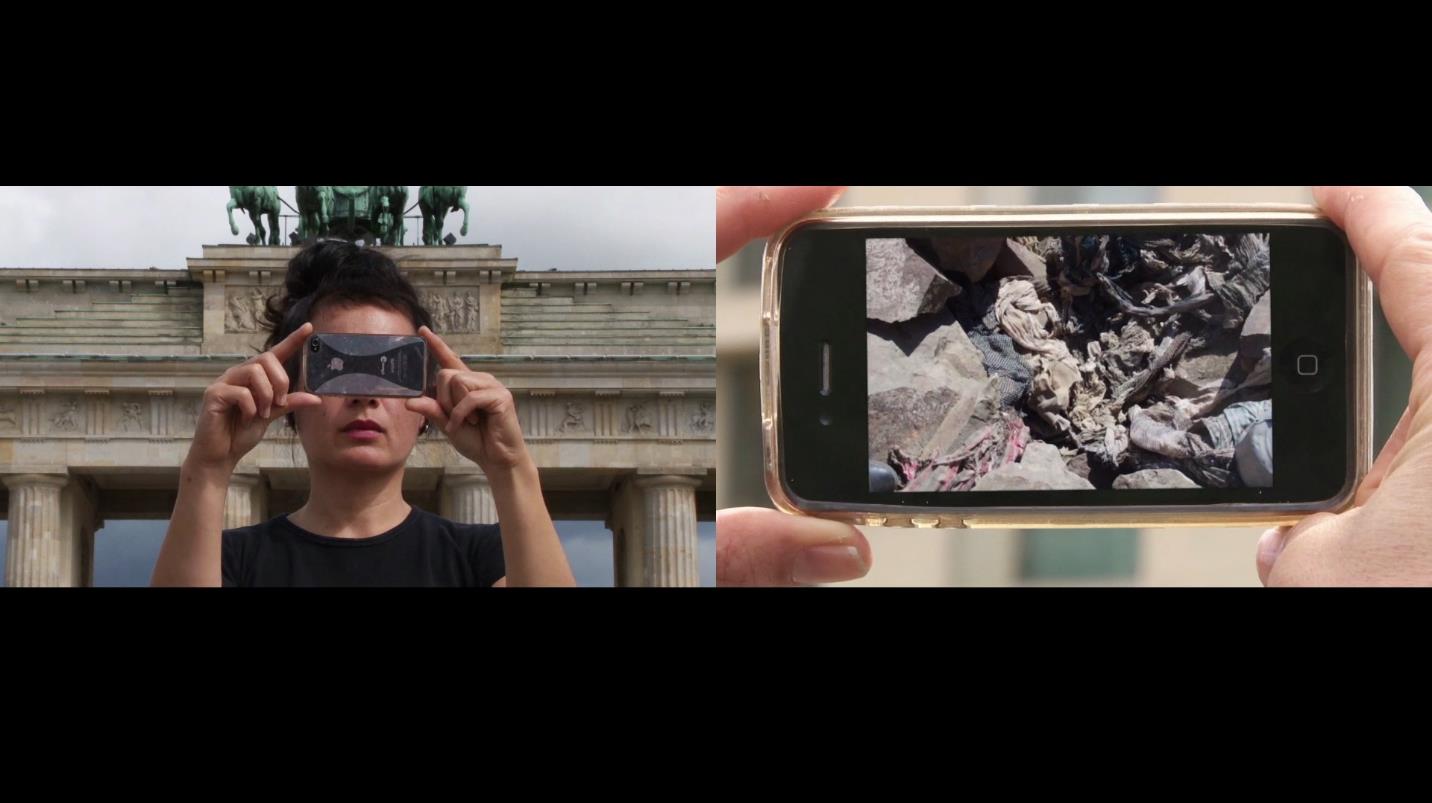

There is Hito Steyerl standing among the crowd at Pariser Platz in Berlin. In front of her she holds up a smartphone, which is positioned to precisely obstruct our view of her eyes. An analog to this image can be found in Steyerl’s short video How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013). Ironically assuming the form of an instructional video, How Not to Be Seen explores the possibility of concealment in a world where visibility is the rule. In the second “lesson” of the piece, Steyerl posits the act of taking a picture as a technique of invisibility.

Again, here, the artist’s eyes are screened off, her gaze replaced with that of the smartphone camera. It is no mistake if this device reminds the viewer of a censor bar, for it has the effect of de-individuating Steyerl, de-emphasizing her status as author and resituating her as a subject bound by the same rules and processes of digital mediation as the video and its spectators. At the same time, the composition of this shot could lead the viewer to wonder whether Steyerl is taking a picture of herself, or of the camera that records her, or of the viewers (us) regarding that recording. This confusion becomes a generative one in Abstract, for it is precisely this device that will suture artist, spectator, and recording apparatus into an unlikely interchange throughout the video.

By repurposing the visual language of the censoring cut and recasting it as a material object in the mise-en-scène, Steyerl also displaces the classical means of linking shots: namely, eyeline matching, where the off-screen direction of a subject’s gaze becomes synonymous with the viewer’s desire to see beyond the frame, thus grounding the progression and accumulation of shots. Consider again how Steyerl’s video begins. First, we see handheld footage of Kurdistan, designated in the video as “shot.” This is followed by footage of Steyerl holding up the smartphone in Berlin. Typically, in a shot/reverse-shot scheme, the one bearing the gaze is first depicted, followed by a shot of what they see, but Abstract inverts that scenario by beginning with the point of view and following that with a shot of the one ostensibly bearing that perspective. Even though the smartphone’s screen has not been disclosed, the viewer can already infer a connection between these first shots—that what Steyerl is looking at is the Kurdistan footage, and that the device itself is somehow a hinge between these spaces. As we will see, by displacing her gaze with that of the smartphone, Steyerl builds a bridge not only between images and screens, but between Kurdistan and Germany, viewer and artist. The space between “here” and “elsewhere,” “shot” and “countershot” is collapsed here onto the surface of a smartphone, while the viewer, poised between these terms, becomes a kind of intervallic figure: a third “shot.” Moreover, the associations being drawn here unfold in a gradual, “soft” manner, and indeed, the process of association itself is already a central subject of “display” here.

Following this initial sequence of shot/countershot—of Germany/Kurdistan—a new statement emerges: “The grammar of cinema follows the grammar of battle.” The words hang there across two screens before evacuating, and we hear a missile launching and detonating. What follows emerges as if from the rubble of this discourse that has just been articulated and exploded.

Soon, on the left-hand screen, we get a shot revealing more of the surrounding territory in Kurdistan. This time, the image is accompanied by the testimonial of an elder Kurdish man. A new statement appears on the right-hand screen: “This is an interview.” The man recalls the events surrounding the raid to Steyerl and her translator—how multiple Cobra helicopters that swept in and kept “shooting and shooting and shooting.” When he utters the word “shooting” for a third time, both image and sound evacuate, giving way to a new shot on the right depicting the same pile of rubble from before. “This,” we are again told by onscreen text, “is a shot.” It begins on a rapid zoom inward, charging like a bullet towards its target, until settling upon that unassuming pile of rubble which, we later learn, is a collapsed cave where the vanquished PKK militants were buried by Turkish armed forces. The velocity of this inward camera zoom, coupled with the fact that it appears directly after the thrice-uttered word “shooting,” suggests an analogy between the video camera used to record these images and the artillery affixed to military helicopters. But as we will see, Steyerl makes this connection not in order to reinforce the cinematic grammar of battle, but rather to transpose the space-defying, border-crossing means of firearms and artillery toward the ends of excavation and rescue.

The shot of the burial site soon disappears, and again, on the left-hand screen, we see Steyerl at Brandenburg gate holding a smartphone up at eye level, again attended by the sentence, “This is a countershot” on the right. The sentence gives way to a new shot, and for the first time, both screens are occupied by video footage. The new shot is directed downward at the ground above the burial site, littered with signs of life and struggle.

With grim limpidity, the Kurdish man designates objects among the wreckage. “This is a blanket”; “This is a piece of cloth”; “This is a jacket”—he names these items with careful precision, often holding them up or pointing to them with a long stick as if to foreclose on any occlusion in referential passage. The shot on the right then disappears, and again we are left only with an image of Steyerl holding the smartphone in Berlin. In the place of the former, a familiar sentence emerges: “This is a shot.” By now, it is worth noting that the construction, “This is a...”, has been employed in the naming of such a diverse collection of objects and forms that the distinction between the domain of the image (shot/countershot) and that of things (jacket, coat, ammunition) has all but dissolved. This turbulent accumulation of things both material and digital effects a “soft montage” between profilmic and filmic space, of gunshots and video shots, testimony and battle.

The next shot that appears reveals the screen-side of the smartphone for the first time in the video. On it, we see the earlier footage of Kurdistan, while the shot of Steyerl holding the phone persists on the left-hand screen.

This pairing of shots comes closer than perhaps any other in Abstract to the classical form of shot/countershot. Were these images to be seen in succession rather than simultaneously as they are here, the shot on the left would disclose a discrete amount of information up to and including its frame (i.e., lack of information), while the shot on the right would expand that horizon with the revelation of new content, retroactively compensating for the lack in the previous shot’s visual field. But Steyerl’s use of shot/counter-shot here departs in crucial ways from this classical scenario. We have already touched upon one of these distinguishing factors, which consists in the way Steyerl obscures her eyes and thus denies the spectator their traditional viewing surrogate in the mise-en-scène: a gesture that on its own implicates viewers in the process of editing. At the same time, by figuring the smartphone so prominently both as an object and subject of vision, Steyerl further blurs the boundaries between shot and counter-shot, image and screen, collapsing the signifying chain onto the screen of the smartphone. In this way, we could say that the shot on the right denies the shot/countershot dyad its conventional telos in the linearization of perspective and narration of continuous space. Rather than proceed in service to a cumulative orchestration of presence and lack, in Steyerl’s video shots appear, disappear, and resurface in a soft montage that gradually reveals rather than insists upon associations at once spatial, temporal, and conceptual.

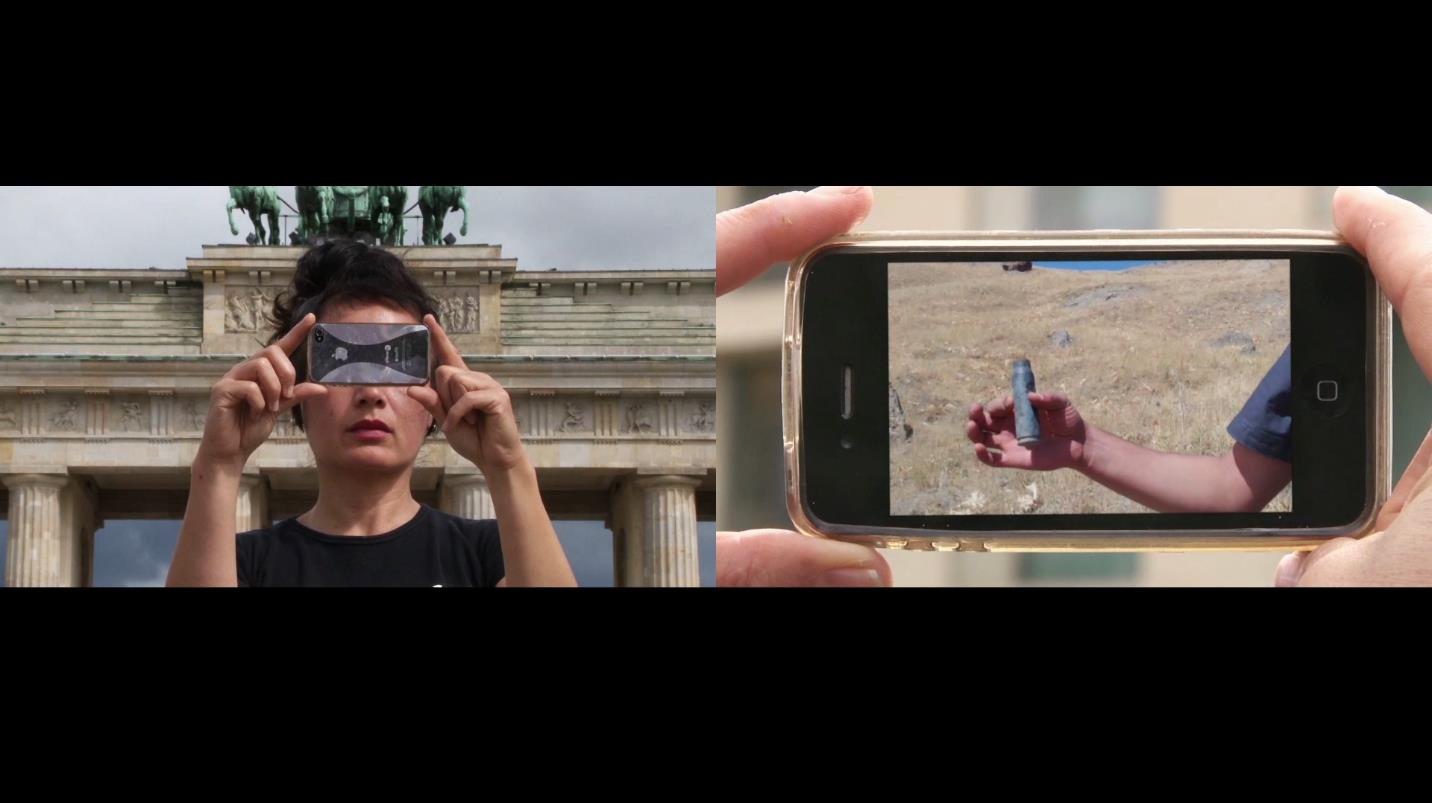

At one point, Steyerl’s translator picks up an ammunition shell left over from the raid and holds it up for closer inspection.

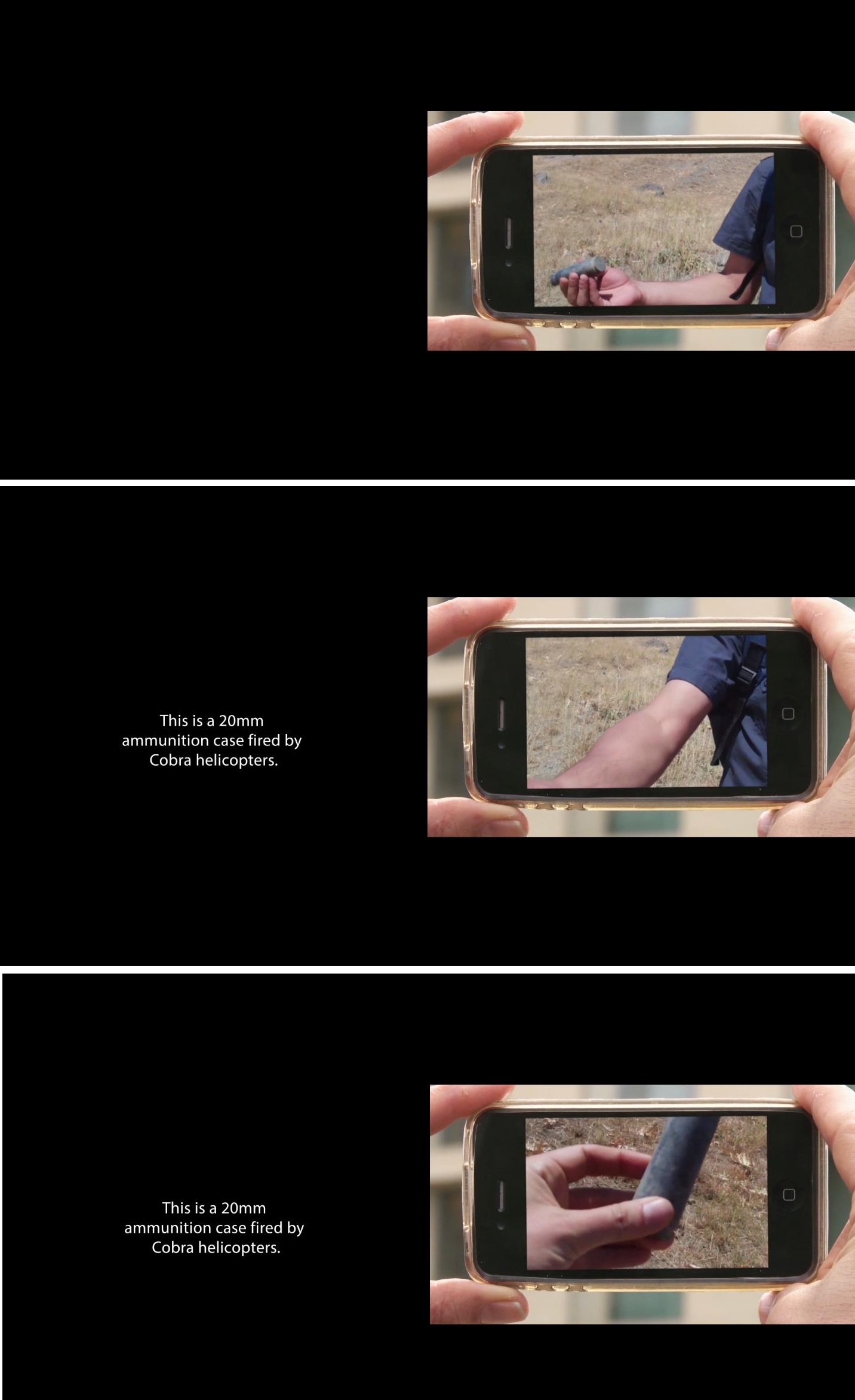

The shot of the artist on the left disappears, while on the other screen the man passes the shell to Steyerl. Precisely when this object passes into the space beyond the smartphone screen, the following text appears: “This is a 20mm ammunition case fired by Cobra helicopters.”

At this moment, the video almost seems to collect the ammunition shell into its discourse, much as the villagers had when, as the guide attests, they gathered various pieces of wreckage from the raid in its aftermath. The image of Kurdistan on the right, which itself appears on the smartphone screen, is now directed towards another portion of the collapsed cave. When Steyerl’s guide speaks of rocket shells that were found beneath the rubble, a new shot appears on the smartphone, consisting of slow-motion footage depicting a rocket shell buried beneath the dirt. Further text appears on left: “This is a Hellfire missile fired by Cobra helicopters.” When this sentence disappears, a shot figuring Steyerl from behind appears in its place, and immediately thereafter the shot on the right disappears, leaving us once again with Steyerl in Berlin.

But something has changed. As if by the same mechanism that switches the smartphone camera’s point of view, here, for the first time, we see the off-screen information that was merely implied by the earlier shot depicting Steyerl from the front. But the field of vision has expanded.

In the background is the Frank Gehry-designed DZ Bank building in Pariser Platz. As before, Steyerl raises her arms at eye level as she grasps the smartphone, which is eclipsed in this shot by her head. On the right-hand screen, the shot of the buried missile shell persists on the smartphone, until the entire shot disappears and is replaced by the sentence, “This is a countershot.” Both screens then go black, leaving us only with the sound of wind.

Soon, an altogether new configuration emerges. It consists of the same shot depicting Steyerl from behind, and an additional one depicting her from the front.

While it is possible to characterize this configuration in terms of shot/counter-shot, it is distinguished by the fact that each image depicts the same, solitary subject (Steyerl) at opposite ends of a single line of action simultaneously, conveying the impression of a 360-degree field. This is because any shot that follows from one occurring on the line of action may, according to the rules of continuity editing, be taken from any angle and still maintain the impression of spatiotemporal continuity. And yet, the field being expanded here is not a result of the camera’s position in relation to the immediate space or action around it per se, but rather acts a visual analogy for a much wider dilation of the cinematic field: one in which, as Steyerl remarks in her film November (2004), “Kurdistan is actually here, in Germany.” Throughout Abstract, shots appear and disappear as if the installation were itself a contracting and expanding topography. But this configuration of shot/counter-shot can further be distinguished by the fact that it turns not on a human line of sight, but rather on a technological gaze. As Steyerl threads it into the structure of Abstract, the smartphone, in conjunction with the editing across two screens, effects passages between shots and spaces, enabling the complex work of geographical transpositions occurring throughout the piece.

Soon, the shot depicting the artist from the front will disappear and the following sentence will take its place: “This is the company Lockheed Martin that produces the missiles.” When this sentence disappears, once again we see the smartphone screen from Steyerl’s perspective. On it, the Kurdish elder continues to elect articles among the wreckage. “These are all belt scarves—they wrap around your hip. All these are belt scarves.” By now, the breathless labor of this inventory appears to have exhausted its speaker. “39 people were killed,” he says, and the soundtrack takes leave of this speech and is overcome by the sound of wind. The shot on the left depicting Steyerl in front of the Lockheed-Martin building disappears, while on the right, on the smartphone screen we see fragments of bone amid various pieces of clothing and debris. Soon after this, Steyerl lowers the smartphone down below the frame, and the focus of the shot pulls from foreground to background, where we now see the exterior of the Lockheed Martin’s Berlin headquarters in full relief.

What happens in this instance is a kind soft montage within profilmic space, where the image of a human bone fragment in Kurdistan is transposed onto the surface of a building in Germany. Directly after this rack focus, a new sentence appears on the left: “This is where my friend Andrea Wolf was killed in 1998.” What we encounter here is a stirring in the deixis of place, for the implication is that Wolf’s death occurred in two places simultaneously. This slippage, which only furthers the video’s gradual superimposition of Kurdistan and Berlin, is less an oppositional act than an analogical one. That is, the conceptual and technical apparatus animating Abstract is not geared toward decisively hitting a distinct target, but rather toward the disclosure of a system within which seemingly disparate materials and places circulate and exist simultaneously within unified creative geography, including the artist herself.

*

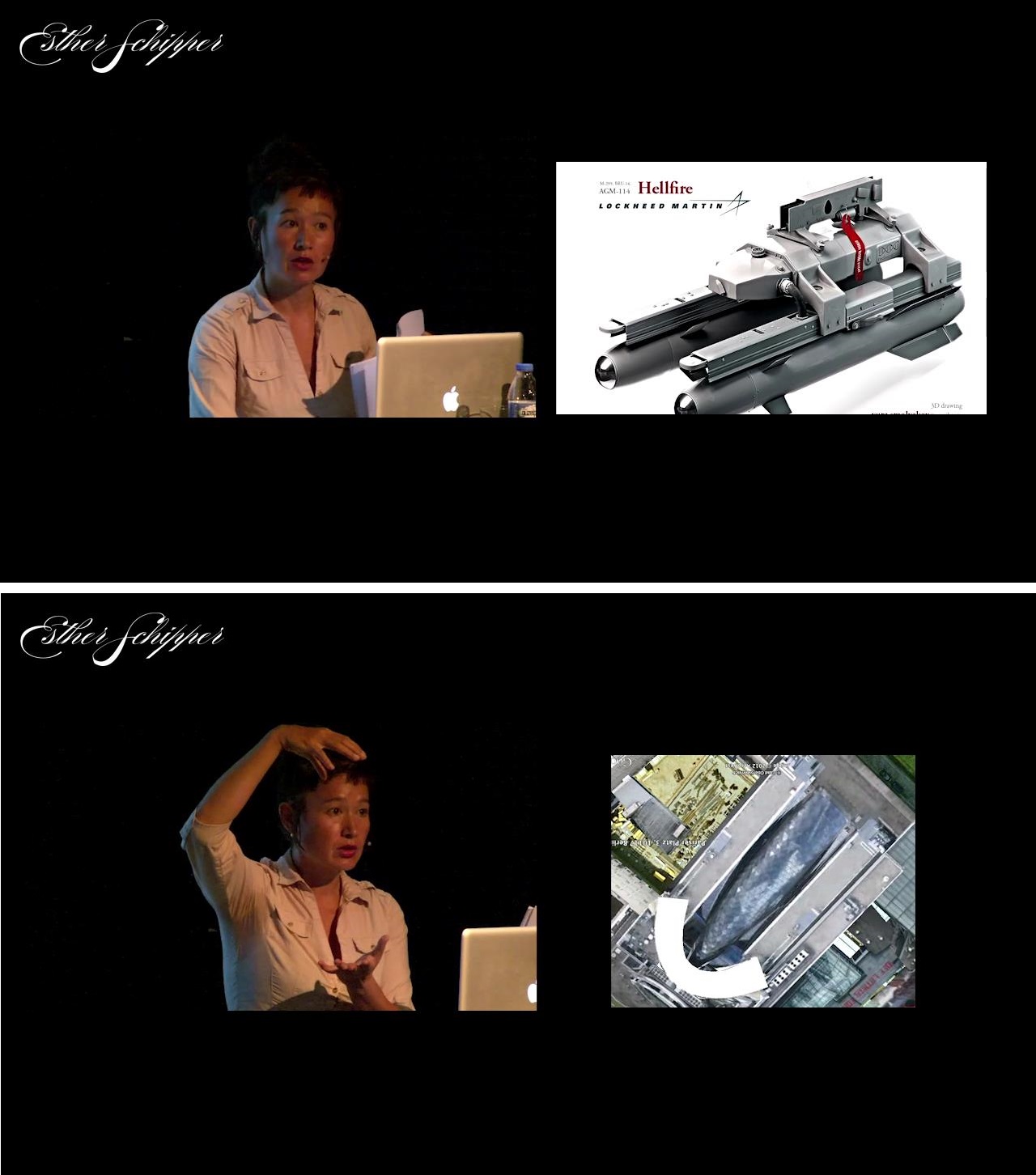

Steyerl’s performance lecture Is the Museum a Battlefield? (2013) functions as something of a postmortem reflection on Abstract. In it, the artist states that her goal in creating Abstract was to “follow a few pieces of debris back to their makers, back to their manufacturers, back to the places they were launched from initially.”[28] In other words, the operative assumption here was that of a relative constancy, from origin to destination, of deadly projectiles: specifically, that they are beholden to the same laws of physics as any other material object, such that one could trace an ammunition casing back in space and time to a point of origin. But as Steyerl goes on to suggest, the technology of war does not follow such laws of physics. In conveying this idea, she points out an intriguing coincidence in the visual appearance of Lockheed Martin’s Hellfire missile launcher and their corporate headquarters in Berlin: a “perfect match,” as Steyerl puts it somewhat ironically.

This analogy between a Frank Gehry-designed building and an apparatus manufactured for death suggests a kind of quantum volatility of matter where a missile can transform, midflight, into a work of art.[29] While this analogy is not to be taken literally, it does have a certain explanatory power. To elucidate this, we might consider Steyerl’s discussion in her lecture of a 20-mm projectile manufactured by General Dynamics, whose casing features so prominently in Abstract. This object reveals yet another facet of the strange physics of capital and war that discloses a link not only between “starchitecture” and missile launchers, but video art and Gatling guns.

In 2013, the Art Institute of Chicago staged a major solo exhibition of Steyerl’s work. There, Steyerl found herself in front of Abstract, standing in a museum that draws major financial support from the Crown Family, whose patriarch, the late American industrialist Henry Crown, in 1959 became the largest shareholder of General Dynamics Corporation: one of the largest defense contractors in the United States.[30] Upon seeing Abstract displayed at the SAIC, a strange feedback loop revealed itself to Steyerl: “I found a picture of myself... shooting video on an iPhone, with the caption, ‘This is a shot’. So, did I shoot the bullet I found on the battlefield myself?” This question is perhaps less an invitation to further Steyerl’s paranoid reading of her own video than to consider a fundamental tension running through her work: that of a certain difficulty posed to any critique of violence under this advanced stage of global capitalism. Of course, the case of the SAIC is but one illustration of the cultural sphere’s non-exemption from the global workings of state violence and war. It is telling of this larger difficulty that, in the “Battlefield” performance, when Steyerl purports to hold up the 20-mm bullet to give form to the object of her critique, the bullet is invisible: she comes up empty-handed.

Toward the end of abstract, in a voiceover, Steyerl’s guide recounts how Andrea was captured alive, brutally beaten, and eventually killed by her captors. On the right-hand screen, we again see Steyerl in Berlin, while the shot on the left now depicts Steyerl holding her smartphone, the screen of which depicts the guide standing atop a hill in Anatolia. The man’s voice enters the soundtrack once more. “Whenever I see the perpetrators, I think of this horrible act,” he declares, and makes his way down a hill into a valley. The shot on Steyerl’s smartphone holds on this for a moment, until we hear a clicking noise on the soundtrack like the one from the beginning of the piece that preceded the sound of a missile launch and explosion. As we hear this clicking sound, on the right-hand screen we see Steyerl lower the camera below the frame, revealing her eyes. This sound match transposes the clicking sound from the beginning of the film associated with the missile launch onto the act of capturing of an image. She then lowers the smartphone below the frame, even as, on the left screen, she continues holding the device. In this instant, she bifurcates her image, splitting her body in two. Gazing off-screen for a moment as if to regard the scenes of Kurdistan and Berlin simultaneously, Steyerl then walks forward, disappearing off the edge of one screen and reappearing on the other.

Soon, the translator joins her, and both make their way down the hill behind the Kurdish elder. These two shots dwell for some time on their respective screens as we hear the familiar sound of a missile surging through space and exploding. Digital black leader once again fills both screens, attended by one last written formulation:

Shot. | One opens a door | |||

Countershot | to the other |

No longer content to wait for the next image to materialize, Steyerl cuts a door from Germany to Kurdistan. This is not merely a cinematic magic trick, but a simultaneously political and aesthetic gesture. She divides herself in two, extending her flesh across the distance holding Germany and Kurdistan apart. Crucially, this autogenetic act is only thinkable for Steyerl within the realm of the digital, which promises to innervate and link bodies even as it threatens to cut them further, and which forecloses on any definitive separation between shooter and target and much as it does a decisive act of critique. At the same time, this gesture is aligned with Steyerl’s larger efforts to fundamentally reconceive the politics of montage, displacing the model of editing grounded in dialectics and shock—a relic of the avant-garde—for one that is spatial, geographic, and corporeal. Steyerl’s act envisions the cinematic interval as a physical opening in the geographic imaginary, a passage from here to elsewhere. By walking through the cut, she not only reveals hidden relations between places, words, and shots but suggests that those relations must be enacted physically, even as the artist must be prepared to find herself, at any given point, on the wrong side of politics. In seeking out Andrea Wolf, Steyerl cuts a passage into the off-screen, as if to say, where there is no door, make a cut.

Author Biography

Ryan Conrath is Assistant Professor of Cinema Studies at Salisbury University, with a research focus on the politics of montage in moving image art. His work has appeared in Millennium Film Journal, View: Theories and Practices of Visual Culture, and Bright Lights Film Journal, among others. His current book project, The Ecological Cut, examines the historical intersections of ecological thought and aesthetic distanciation within the cinematic avant-garde.

Notes

Hito Steyerl, Q&A with audience at Flaherty Film Seminar, Hamilton, NY, June 14-20, 2014.

Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics, trans. Marc Polizzotti (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2006), 149-150.

Ibid., 150-151. This scenario has become even more acute in the years since Speed and Politics was first written, for the arms race is quickly approaching lightspeed, with US, Chinese, and Russian militaries having either deployed or reached the advanced developmental stages of laser weapons systems.

Harun Farocki and Yilmaz Dziewior, “Conversation October 23, 2010, Kunsthaus Bregenz,” in Harun Farocki: Soft Montages, ed. Yilmaz Dziewior (Bergenz: KUB, 2011), 210.

Alisa Lebow, “Shooting With Intent: Framing Conflict,” in Killer Images: Documentary Film, Memory and the Performance of Violence, eds. Joram Ten Brink and Joshua Oppenheimer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 41-62

Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 124.

Sergei Eisenstein, “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form,” in Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, trans. Jay Leyda, (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1949), 38.

Sergei Eisenstein, The Film Sense, ed. Jay Leyda (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1947), 208.

Santiago Alvarez quoted in Derek Malcolm, “Santiago Alvarez: LBJ,” The Guardian Unlimited, June 17, 1999. https://www.theguardian.com/film/1999/jun/17/derekmalcolmscenturyoffilm.derekmalcolm

Fernando Solanas and Octavio Gentino, “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World,” in New Latin American Cinema vol. 1, ed. Michael T. Martin (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997), 50.

Jean-Luc Godard, “Jusqu’à la victoire,” uploaded November 28, 2012, http://www.diagonalthoughts.com/?p=1728. Originally published in “El Fatah,” 1970. Emphasis mine.

Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Militant Cinema: From Third Worldism to Neoliberal Sensible Politics,” La furia umana 33, http://www.lafuriaumana.it/index.php/66-archive/lfu-33/728-irmgard-emmelhainz-militant-cinema-from-third-worldism-to-neoliberal-sensible-politics.

Thomas Elsaesser, “Harun Farocki: Filmmaker, Artist, Media Theorist,” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sightlines, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 17.

Harun Farocki, “I Thought I was seeing Convicts,” 2000. https://www.harunfarocki.de/installations/2000s/2000/i-thought-i-was-seeing-convicts.html

Harun Farocki and Kaja Silverman, Speaking About Godard (New York: NYU Press, 1998), 142.

Harun Farocki, “Cross Influence/Soft Montage,” in Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, ed. Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (London: Koenig, 2009), 70.

Zur Bauweise des Films bei Griffith/On Construction of Griffith’s Films (Harun Farocki, 2006).

Bernhard Siegert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015), 203.

Harun Farocki, “Controlling Observation,” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sightlines, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 293. Emphasis mine.

Paul Virilio, “The Overexposed City,” in The Paul Virilio Reader, ed. Steve Redhead (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 87-88.

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006), 21-22.

See: Andrew Durbin, “Selfie Poetics,” Mousse 44 (Summer, 2014), http://moussemagazine.it/andrew-durbin-selfie-poetics-2014.

Is the Museum a Battlefield? (Hito Steyerl, DE, 2013), lecture originally given at the 13th Istanbul Biennial, video uploaded October 2, 2013, https://vimeo.com/76011774.

Obituary of Henry Crown by Joan Cook, New York Times, August 16, 1990, online edition, http://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/16/obituaries/henry-crown-industrialist-dies-billionaire-94-rose-from-poverty-by-joan-cook.html.