Freddie versus Maya: A Textual Analysis of Two Narrative Structurations of (Post)colonial ‘Brown’ Subjectivity as read through Lacanian Film Theory

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract:

In this essay, I use Lacanian film theory to critically analyze two biographical films—Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) and Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. (2018)—released in theatres around the same time that portray, using the rags-to-riches trope, two British recording artists who share a South Asian ethnicity.

In this essay, I juxtapose two biographical films released in theatres around the same time that portray—using the rags-to-riches trope—two British recording artists who share a South Asian ethnicity. The films are Bohemian Rhapsody (2018)[1] and Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. (2018);[2] the former is a fictional film, while the latter is a documentary. I also unpack, through a textual analysis of each film’s narrative structuration of (post)colonial ‘Brown’ subjectivity,[3] the strategies that Freddie (née Farrokh Bulsara) and Maya (née Mathangi Arulpragasam) use to negotiate their thrownness[4] as refugees: colonial assimilation and decolonial pluralism, respectively. But before interpreting either film, I will first describe the textual analytic framework informing this essay.

Lacanian Film Theory

Lacanian Film Theory (LFT) is a theory of film spectatorship, which is concerned with how and why we enjoy the films that we do qua how desire is structured in those films. Both the structure of desire in a film and the spectators’ enjoyment are objective because what caused the desire of the filmmaker to make a film in the first place (i.e., the objet a or the object-cause of desire)—particularly if the film is a masterpiece—is precisely what causes the desire of spectators. In other words, films position spectators to enjoy them in specific ways and they have the choice of either accepting or rejecting that positioning, but it is only possible to enjoy any given film from a specific, objective position vis-à-vis the objet a.[5]

Todd McGowan’s taxonomy of the four deployments of the Gaze (the form of the objet a in the scopic drive) is extremely useful in terms of film criticism, especially since it can help film critics theoretically differentiate between masterpieces and typical films.[6] According to LFT, a masterpiece “is a film that confronts the spectator with the irreducibility of antagonism by opting for the objet a instead of presenting the spectator with an obtainable object of desire.”[7] The four deployments of the Gaze, according to McGowan,[8] are: (1) the cinema of intersection, (2) the cinema of desire, (3) the cinema of fantasy, and (4) the cinema of integration.

Masterpieces tend to be cinemas of intersection, wherein desire and fantasy intersect but are kept apart as separate worlds. A good example of this kind of cinema is David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).[9] Other masterpieces tend to be either cinemas of desire or cinemas of fantasy. Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941)[10] is an example of a cinema of desire because the film “continually revolves around an impossible object (suggested by the signifier “Rosebud”). The film repeatedly brings the spectator close to an encounter with this object, but each time the encounter is missed...Kane’s desire remains absent.”[11] Conversely, Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing (1989)[12] is an example of a cinema of fantasy; as McGowan argues: “Lee is fundamentally a filmmaker of fantasy...he uses the fantasmatic dimension of film in order to reveal to us the excess [of racism] that conditions our experience of social reality but nonetheless remains invisible outside of the fantasmatic structure.”[13] While Welles’s films emphasize lack, Lee’s films are centered on excess. Both lack and excess are characteristics of the objet a.

Finally, typical films, which tend to be produced by Hollywood, are cinemas of integration because they domesticate the trauma of desire through recourse to fantasy, which is an ideological move. An example here is Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993)[14]—“a film about the Holocaust [that] is not disturbing enough.”[15] Cinemas of intersection, in contrast, “facilitate a traumatic encounter with the [Real] gaze.”[16]

In this essay, I will show, using LFT, why the critically acclaimed Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. is a much more enjoyable film than the commercially successful Bohemian Rhapsody. This difference in enjoyment can be attributed to dissimilarity in how desire is structured and how the Gaze is deployed in each film.[17] I chose to compare these two films because they share a central theme: a rags-to-riches story of two South Asian immigrants who escaped persecution and relocated to the United Kingdom (UK) when they were young to later on become international music celebrities as adults.

In the ensuing textual analysis, I will make the case that Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. is a masterpiece whereas Bohemian Rhapsody is a typical film.[18] After carefully analyzing the structuring of desire and the deployment of the Gaze in both films, I have come to the conclusion that Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. is a cinema of intersection while Bohemian Rhapsody is a cinema of integration. According to McGowan, a cinema of integration, or a typical film, is “a kind of film that functions ideologically by integrating desire and fantasy,”[19] while a “cinema of intersection [or a masterpiece] allows us to examine what happens when fantasy emerges in response to the dissatisfaction of desire.”[20]

My focus in this essay is more on the narrative structuration of Maya’s and Freddie’s subjectivities as South Asian immigrants and less on their genius as British artists although I will occasionally remark on that, too. In order for me to fulfill the above-stated goal, I will particularly emphasize one element of film form (narrative/dialogue) without ignoring the other elements of cinematography, mise-en-scène, editing, and sound.

Bohemian Rhapsody

The first problem with the narrative structure of Bohemian Rhapsody is that it is a confused film, being two films in one that ends up not doing justice to either, or to put it in simple terms: “The script is deadly. And that’s just the start of our problems.”[21] First, there is a film about Freddie Mercury: his rise to fame, his struggles with his inner demons, and his glorious comeback at Live Aid. Second, there is a film about Queen: how they went from being Smile to becoming one of the greatest rock bands of all time. The Freddie Mercury story, based on what is on screen, is incomplete. Not only that, the story is full of plot holes and historical inaccuracies. For example, Freddie learned about his diagnosis with AIDS in 1987 and not in 1985 like is shown in the film. Also, Ray Forester, the EMI executive, is a completely fabricated character that functions solely as a tribute to Mike Myers for his memorable homage to “Bohemian Rhapsody” in Wayne’s World.

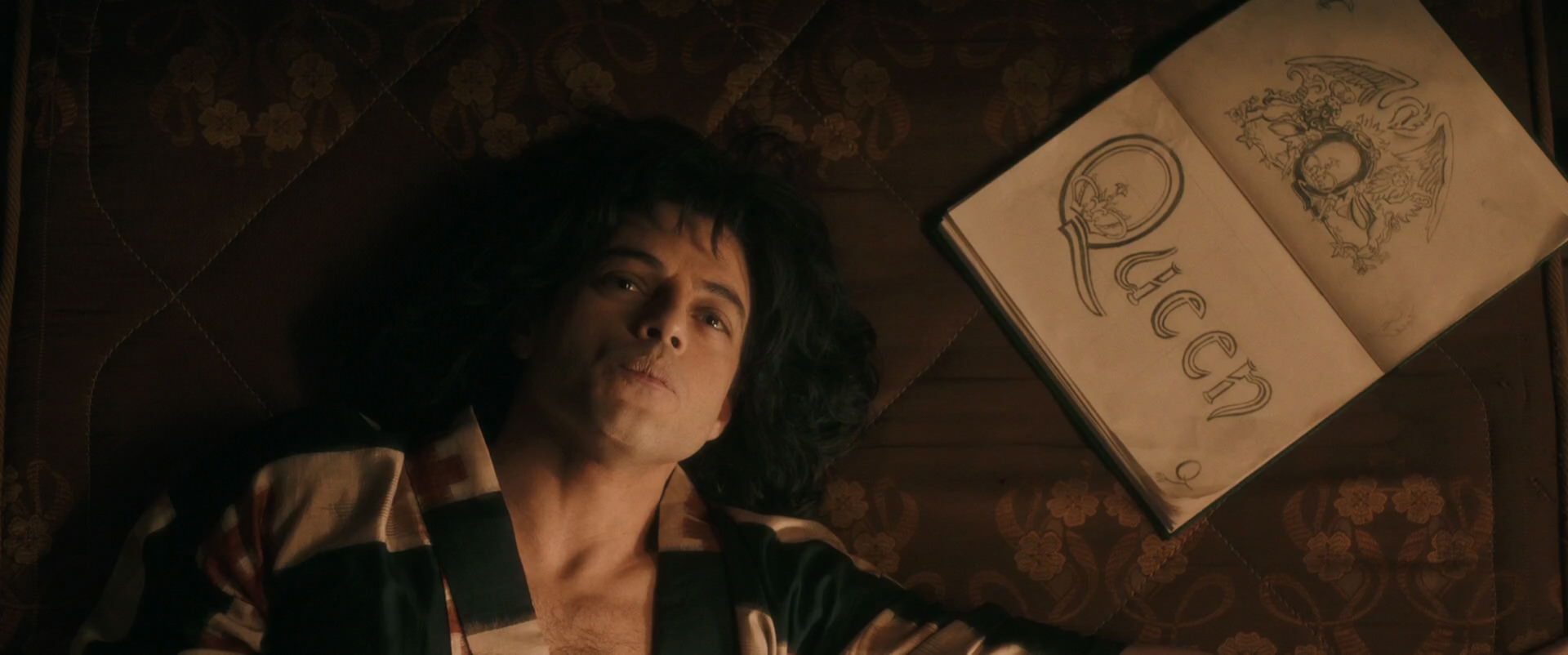

Bracketing the cliché bookending of the film with the band’s performance at Live Aid in 1985, the Freddie Mercury story begins in London (1970) with Freddie as a baggage handler at Heathrow Airport. The film follows a formulaic and, a more or less, chronological three-act structure. In the first act (the set up), we see Freddie Bulsara (rags) becoming Freddie Mercury (riches), but the film never shows us how Farrokh Bulsara became Freddie Mercury.

The key moment in the first act is a silly scene at Freddie’s house, wherein Mary Austin (Freddie’s partner), three quarters of Queen (May, Taylor, and Deacon), and the Bulsaras (Jer, Bomi, and Kashmira) converse about Freddie’s background as an Indian Parsee and his upbringing in Zanzibar, and then look at photographs of young Freddie (particularly as a boxer). Freddie walks away from the group looking unhappy, he sits at the piano and starts playing it while singing: “Happy birthday to me...happy birthday Mr. Mercury.” Kashmira replies, “Mercury.” Freddie responds while staring at himself in the mirror: “No looking back. Only forward.”

From a psychoanalytic perspective, this moment of Imaginary identification, or misrecognition, with a fantasy image (a whitened Farrokh Bulsara) exemplifies Jacques Lacan’s mirror stage,[22] which is not only a developmental stage that the infant goes through as it develops its ego, but also a theatrical stage for the ego’s performance throughout life. After Freddie announces his new surname, Bomi asks, “So now the family name’s not good enough for you?” Jer comes to Freddie’s defense and says, “It’s just a stage name.” To which Freddie responds, “No, it’s not. I’ve changed it legally. Got a new passport and everything.” Bomi is disappointed and later exclaims, “You can’t get anywhere pretending to be someone you’re not.”

Bomi is correct in his assessment, Freddie erased his ego (Farrokh Bulsara) and replaced it with an alter ego (Freddie Mercury), that is, he changed personas or masks, but the unconscious of Farrokh Bulsara lives on. Lesley-Ann Jones sheds light on this motif, which motivates Freddie’s epic poem about coming out: “‘Mama, I just killed a man . . .’ He’s killed the old Freddie he was trying to be: the former image. ‘Put a gun against his head, pulled my trigger, now he’s dead’—he’s dead, the ‘straight’ person he was originally.”[23]

The film is replete with shots of Freddie misrecognizing himself in different mirrors, while admiring his many fantasmatic reflections, or identifying with Mary’s reflection while telling her in an unsettling way: “How beautiful you are.”

The Imaginary order is also the order of fantasies, and it is two-dimensional, which speaks to the film’s overall lack of complexity in terms of story and character development. The Symbolic order is the order of language and Law, wherein we were supposed to learn more about, for instance, Freddie’s ethnic and religious background and how it constituted his unconscious genius as an artist as well as his complexity as a (post)colonial ‘Brown’ subject. We encounter the traumatic Real whenever the Symbolic order fails, and it always fails because it cannot account for everything. AIDS is the most concrete example of the traumatic Real in the context of the Freddie Mercury story, but it features scantily throughout the film.

Freddie’s misrecognition is also an Oedipal moment since with the legal name change Freddie not only erased his ethnicity, but also killed the Name-of-the-Father or the signifier ‘Bulsara’.[24] This leaves him with only the desire of the mOther; perhaps it is no coincidence that the name of the love of his life is Mary as in mOther Mary, particularly in light of this revelation: “‘Mary Austin was Freddie’s mum, in a way,’ reasons music publicist Bernard Doherty.”[25]

Freddie adopted his new surname from a song he wrote called “Fairy King” from Queen’s self-titled first album: Queen (1973).[26] In the song, Freddie sings about “Mother Mercury” alluding to his mother Jer.[27] Paradoxically, “Fairy King” is part of a series of songs that pertain to Rhye, a fantasy world created by Freddie, which is inspired by his Parsee roots.[28] This goes to show again and again that it was impossible for him to erase his ethnicity because that would have amounted to him erasing his unconscious, which is the equivalent of death.

So while Freddie did undoubtedly want to pass for ‘White,’ signifiers from his past still slipped into his music as is clear in songs like “Bohemian Rhapsody” and “Mustapha,” which contain Arabic signifiers that are associated with Islam. Signifiers like ‘Bismillāh’ or ‘Allāh’ that he must have heard while he was a child in Zanzibar (a Muslim-majority country). These repressed signifiers, which returned to him, as an adult living in the UK, were implicitly expressed in some of Queen’s songs, and they relate to Freddie’s struggle with being queer because in both Zoroastrianism and Islam queer sexuality, or identity, is absolutely immoral to say the least.[29]

The reason why I am unpacking the scene of Freddie’s birthday in depth is because the most interesting parts of the Freddie Mercury story—Farrokh’s upbringing in Zanzibar and in India between 1946 and 1964 as well as Freddie’s relationship with Jim Hutton since 1985, his battle with AIDS since 1987, and his collaboration with Montserrat Caballé in the same year—were erased, or whitewashed, by the producers (Graham King, Brian May, and Roger Taylor) echoing Freddie’s erasure of his old ego (Farrokh the boxer), maybe because he felt boxed in? However, even though Freddie did erase his old ego, he could not erase his unconscious as is obvious from his dynamic movements on stage as a performer, which are an evident manifestation of his background in boxing, for example.

The most obvious repression of queerness is the name of the band itself (Queen), which Freddie chose and designed the logo for—a feat he does not get enough credit for and, which is only briefly shown in the film as if it were insignificant. Let me remind the reader that, according to LFT, the unconscious (queer) is hidden in plain sight (Queen). There are a couple of clues in the film regarding this link that the narrative never explicitly sheds a light on. For example, at Rockfield Farm in 1975, when the band was arguing one day about the significance of the Taylor’s song “I’m in Love with My Car,” Freddie interrupts the discussion by saying: “Roger, there’s only room in this band for one hysterical queen.” Hysteria, of course, is a key signifier for psychoanalysis and—aside from the oppressive history of that diagnosis being exclusively attached to women in the Victorian Era—it signifies, for Lacan, a subject position (the Hysteric) that questions the Master and produces critical knowledge as a result.

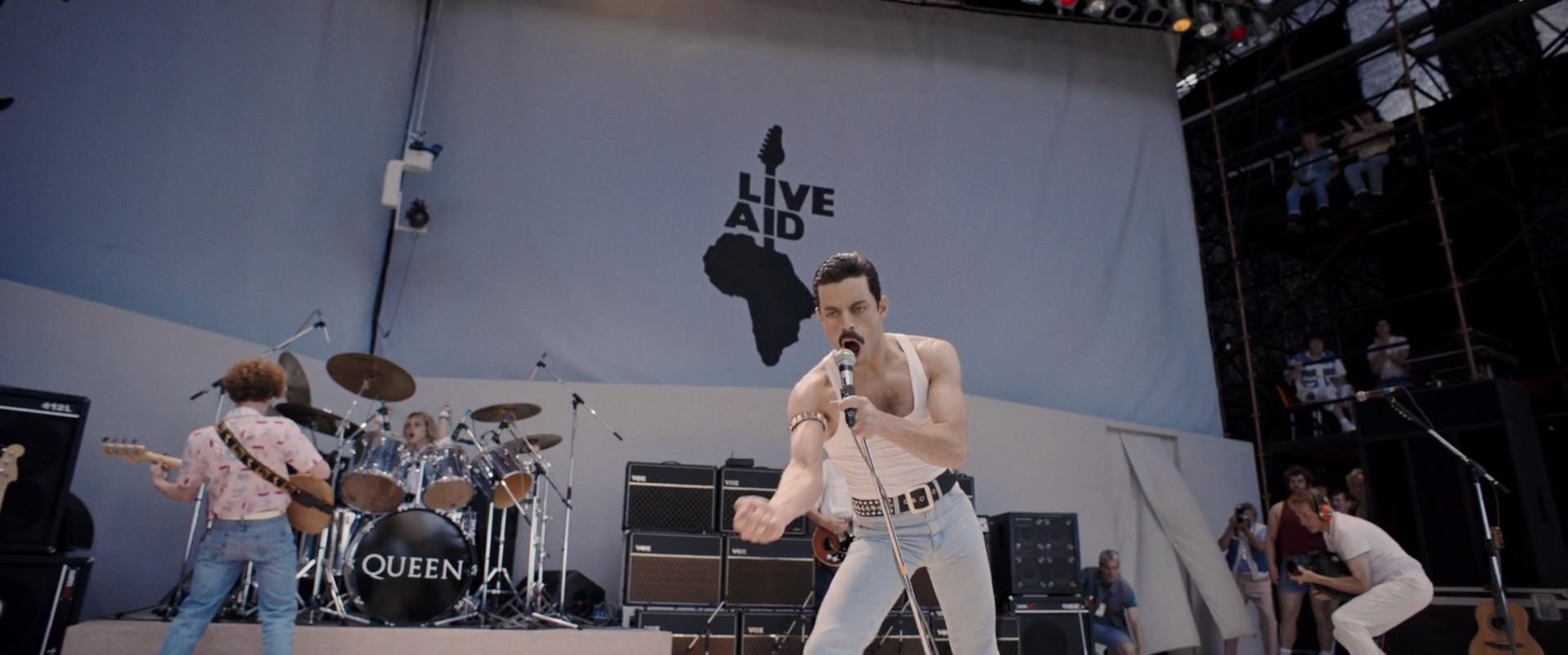

The second clue comes in the third act (the resolution) when Freddie is supposedly redeeming himself and getting the band together for Live Aid, which is historically inaccurate because the band never split up to begin with neither did Live Aid depend on them as the film shows. Freddie, in the presence of Jim (Miami) Beach, tells the other members of Queen: “Let’s face it. We’re not bad for four aging queens.” At this point, queerness is equalized among the band, hence, rendered meaningless, which is the whole purpose of the redemption subplot (if everyone is queer, no one is queer).

Queen was queer, or radical, because of Freddie, and his queerness was a function of both his sexual identity and his ethnic/religious background. The conflict between the former and the latter is what the film should have been about, and that would have resulted in masterpiece about a (post)colonial ‘Brown’ subject making it big as a musical genius while making sense of himself as a complex queer. The producers fired Sacha Baron Cohen for arguing against May and Taylor’s whitewashing of Freddie’s complexity: “They wanted to protect their legacy as a band.”[30] The film’s simple narrative is at odds with Freddie’s complex subjectivity.

I sympathize with Freddie’s (and Maya’s) struggle as an immigrant myself, but I have no respect for how Bohemian Rhapsody dishonestly whitewashed Freddie’s background because according to Jer (his mother): “Freddie was a Parsee and he was proud of that.”[31] The producers’ sanitized (PG-13) version of events resulted in a deeply flawed film, which is full of plots holes and historical inaccuracies. In cinema, there is a way of working with holes masterfully because, after all, the Gaze is “a hole within the ideological structure.”[32] Any Symbolic order, by default, is full of holes, or “paradoxes of logic.”[33] For example, one way of deploying the Gaze without suturing these holes is “the cinema of desire [which] sustains the gaze as a structuring absence and an impossibility.”[34] However, the holes in Bohemian Rhapsody that pertain to Freddie’s ethnicity as an Indian Parsee, his religion as a Zoroastrian, and his queer sexuality are sutured ideologically through a recourse to fantasy, which renders the film a cinema of integration. This deployment of the Gaze also explains why the film is ahistorical.

The film pacifies the spectators through fantasies of Whiteness, and rock stardom, without traumatizing them with the Real of queerness and AIDS—except for one anamorphic close up shot, that is reminiscent of the gazing skull in Hans Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors (1533).[35] In the eerie shot, we see Freddie’s expressionless face masked behind a pair of large sunglasses, which reflect the doctor who tells Freddie about his HIV positive diagnosis.

The film also fails to cause the desire of its spectators because of the absence of Symbolic discourses of Brownness (e.g., Zanzibar, India, Islam, Zoroastrianism, etc.). For instance, when Freddie passed away, his family performed a traditional Zoroastrian funeral for him and he was cremated, but somehow that was not important enough to include in a biographical film about Freddie Mercury (or was the film about Queen?), for it was more crucial to emphasize Freddie’s gayness (as opposed to his queerness) from a heteronormative perspective and it was also more significant to stress his Pakiness (as opposed to his Parseeness) from a ‘White’ British perspective.

Here is a general sense of how the film represses Freddie’s queerness: “Because Bohemian Rhapsody only equates queerness with sex, and because it frames his queer lifestyle as bad, Mercury’s subsequent AIDS diagnosis is inherently set up and portrayed as a punishment for his queerness.”[36] A clear example of this repressed queerness comes early on in the second act (the confrontation) in a scene between Freddie and Mary, wherein he comes out to her as bisexual, but she immediately rebuts him by saying: “Freddie, you’re gay.” This is the same Mary who six or seven years earlier at Biba, the fashion store where she worked, told Freddie in the most Orientalist way possible: “You have such an exotic look.” Then she starts putting eyeliner on him and dressing him up using women’s clothing. In a moment of Imaginary misrecognition, they both stare at the mirror in a daze and then Mary tells Freddie’s image: “I love your [queer] style.” In other words, his queerness had to remain unconscious or repressed, and to be expressed only in his “style,” for him to be loved. Once his queerness became conscious (e.g., him coming out to Mary and the rest of the world), it was equated with gayness or sexual promiscuity, which is a lot of what the second act deals with: the demonization of his queerness.

Throughout the film, Freddie gets othered by Mary, by the other members of Queen, and by a variety of random characters, which goes to show that Freddie was loved not for who he was in all of his complexity, but that he was admired fantasmatically for what he sounded, or looked, like within the framework of Orientalism. As Lacan shows,[37] the Voice (one of the four partial-drives) is the form of the objet a in the invocatory drive, and it is mainly how Freddie caused the desire of his millions of fans. Freddie possessed a vocal range of more than three octaves (F#2 → G5) thanks to being born with four supernumerary incisors, for which he was constantly ridiculed as a child being called “Bucky.” To recap, ‘Brown’ artists (like Freddie) cause our desire because of how they embody the Gaze and/or the Voice. However, they have to be exceptional geniuses, not ordinary artists, because of the way ‘White’ privilege works in Euro-America, or as Chris Rock put it: “the black [or brown] man [sic] gotta fly to get to somethin’ the white man [sic] can walk to.”[38]

In the film, Freddie is racialized with the ethnic slur ‘Paki’ three times: first, by a co-worker at Heathrow Airport; second, by an audience member at a Smile concert; and third, by Paul Prenter (the film’s gay super-villain) on German TV. These racist instances of racialization are never really counteracted in the story with Freddie’s actual ethnicity as an Indian Parsee. Other moments of othering in the film include: when Taylor responds to Freddie wanting to join Smile with: “Not with those teeth, mate”—mind you Taylor was a dental student—; when a random group of skinheads call him a “wanker” in public; when May comments on his outfit by saying: “I didn’t know it was fancy dress, Fred” followed by Taylor’s comment: “You look like an angry lizard”; or when Taylor describes Freddie’s new look (growing a mustache and having shorter hair) as “gay-er.” These micro-aggressions speak to the Orientalist, homophobic, and racist undertones of the film, which are never resisted, in an anti-oppressive manner, by the film’s narrative structure.

The film received an Oscar for Best Editing when it has one of the worst scenes in the history of film editing. I am referring to the exterior scene (a café by a river), wherein the members of Queen meet their soon-to-be manager John Reid—and his assistant Paul—for the first time. As Flight argues, “the cuts in this scene are particularly jarring. They stand out to an attentive audience member for three reasons: first, many of the cuts are unmotivated; second, many ignore spatial continuity; and, third, the pace is simply too fast.”[39] Flight compares the editing of that scene to a fight scene from Transformers: The Last Knight and concludes that the former (a drama) is 30% faster than the latter (an action film), which is an artificial way of making sure spectators remain interested in a poorly told story.

One of the things I have noticed watching the extras of Bohemian Rhapsody is the over-presence of the producers (Graham King, Brian May, and Roger Taylor), the actors (Rami Malek, Lucy Boynton, Gwilym Lee, Ben Hardy, and Joe Mazzello), and the design team (led by production designer Aaron Haye) in contrast to the evident absence of the directors (Bryan Singer and Dexter Fletcher), the screenwriters (Anthony McCarten and Peter Morgan), the cinematographer (Newton Thomas Sigel), and the editor (John Ottman).

I understand why Singer was excluded; several men have accused him of sexual misconduct.[40] I also comprehend why Fletcher was barred because the “Directors Guild of America requires in its contracts that each film may have only one director or directing entity, if the two directors are established team.”[41] The cinematographer appeared once in the extras to address the acting and not the cinematography. For instance, the soft lighting of many of the scenes taking place in the 1970’s exacerbated the tackiness of the film’s dreamy look. Meanwhile, the screenwriters and the editor did not materialize once in the extras. This behind-the-scenes drama contributed to the film’s weakness because Bohemian Rhapsody is a product (and not a film) in the most technical sense of the word: producers, and not creators, made it.

The CGI, particularly in the last sequence of the film (i.e., the Live Aid concert), looks very synthetic. On the one hand, it is impressive to see the filmmakers recreate Live Aid with precision; on the other hand, it is a very vapid 15-minute long sequence because it leaves the spectator wanting to simply go and watch Queen’s original Live Aid performance without the well-rehearsed lip-syncing or the excessive CGI.

Rami Malek, who is the first Egyptian American to receive an Academy Award for Best Actor, was phenomenal in the film. His performance is what saved the film from being a commercial flop, but Malek’s acting is just one element that was greatly enhanced by an excellent design team who deserve to be named for their outstanding work: Polly Bennet (movement coach), Julian Day (costume designer), Jan Sewell (hair and makeup designer), Becky Bentham (music supervisor), and Annie Skates (vocal coach). As a result of this, Malek moved, looked, and sounded like Freddie, but that does not change the fact that Freddie was written as a two-dimensional character in the midst of an ocean of one-dimensional, or zero-dimensional, characters.

Bohemian Rhapsody is a typical film because it is so generic, and nothing captures how generic the film is than the presentation of this peak experience (Queen’s first US tour), which is near the end of the first act: “when Queen embarks on their first American tour: ‘Midwest USA.’ Not ‘Cleveland,’ or ‘Detroit,’ or ‘Kansas City,’ but just ‘Midwest USA.’ There’s not even a comma. That’s the degree of specificity in play here.”[42]

Finally, I want to write about Freddie’s cats, for he had many of them, and I must confess that I am a biased cat lover like the majority of the Internet. Throughout his lifetime, Freddie’s cats included: Tom, Jerry, Tiffany, Dorothy, Delilah, Goliath, Lily, Miko, Oscar, and Romeo. One of the most redeeming things about the film, aside from Malek’s performance and the overall convincing mise-en-scène that gave the film a facade of verisimilitude, are the many shots of Freddie’s cats staring at him admiringly, moving on his piano, enthusiastically eating breakfast, or infinitely purring. The cats are not just props in the mise-en-scène; they actually play a crucial role in the film’s narrative structure. Our desire as spectators is aligned with the desire of Freddie’s many cats: we admire and love Freddie (as an objet a) because of how he causes our desire with his Voice. This is the reason why the film succeeded commercially; it has nothing to do with the film itself and everything to do with how spectators a priori feel about Freddie, and everything that he does, even before watching the film.

One of the reasons that Mary broke up with Freddie is not because she thought he was gay but because she came to realize that she is just another cat, or essentially a pet, in his milieu. The crucial moment in the film (the midpoint of the second act), wherein Mary realizes this, is when she asks him after he came out to her as bisexual: “What do you want from me?” This question is one of the most important questions in psychoanalysis.[43] Freddie responds, “Almost everything.” He pauses then adds, “I want you in my life.” Freddie’s demand is impossible, for he wants her in his life as a 24/7 pet and a later scene confirms this unrealistic, almost childlike expectation.

Mary moves next door to Freddie’s lavish new place and they talk on the phone while turning on and off their lamps, but Mary does not look entertained by this game, she wants more: a straight man. Freddie’s queer desire is insatiable like the Queen song: “I Want It All.” Mary replies to Freddie’s demand and desire with a question: “Why?” To which he answers, “We believe in each other. And that’s everything. For us.” The scene ends with the following ominous line from Mary: “Your life is going to be very difficult.” It is not clear what exactly she is referring to; one hopes she was not wishing AIDS on him as punishment for rendering his unconscious queerness conscious? Mary then walks away leaving Freddie in tears. And, of course, there is a shot of the cats looking empathic with Freddie, which is exactly how we feel as spectators. We want what the cats want (a happy Freddie) and our enjoyment is empathic, too. This possibility of Freddie being happy is alluded to in the film (e.g., his relationship with Jim Hutton), but it is never really explored, neither is the tragedy of AIDS; hence, the generic narrative structure.

Matangi/Maya/M.I.A.

Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. goes to show that a film can have a raw aesthetic (as opposed to a well done aesthetic like in Bohemian Rhapsody) and still be not only a more enjoyable film, but also a masterpiece (as opposed to a typical film). As a refresher, a “cinema of intersection allows us to examine what happens when fantasy emerges in response to the dissatisfaction of desire.”[44] In masterpieces, fantasy and desire are two intersecting worlds, which are kept apart. In typical films, the two worlds are integrated in an ideological fashion.[45]

In Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., the world of fantasy is the world of pop stardom, which for Maya, begins in 2003 with the release of her hit single “Galang.” Unlike the linear plot of Bohemian Rhapsody, Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. unfolds through a non-linear narrative structure. The film begins at the end (without the use of bookends). The scene before last, in the film, shows Maya sitting next to her grandmother inside their family home in Sri Lanka (2001). The scene has a melancholic feel to it because Maya is about to leave Sri Lanka for the UK, and she does not know if she will be able to come back to her home country and, if she is able, she is uncertain whether or not her grandmother will still be alive.

We learn earlier in the film that Maya’s grandmother lost an eye during the Sri Lankan Civil War because the military bombed the car she was in thinking she was a Tamil Tiger. Incidentally, we see many images of the Tamil Tigers throughout the film, in particular images of female fighters, who cause the desire of Maya to make original audio-visual artwork directly inspired by them. Maya fully understands that if she were not living in the UK as a refugee, she would have been a fighter like them in the jungle. That deep realization informs her fighting spirit as a transgressive artist who speaks truth to power.

In film’s almost final scene, the grandmother is singing, and here is the dialogue that unfolds between them in Tamil. Maya asks: “Do you have any life advice?” The grandmother answers: “Live a happy life like I do.” Maya: “For my life?” Grandmother: “I keep on singing songs, and it makes me happy.” Maya: “So what should I do?” Grandmother: “You should sing too!” Maya chuckles. Grandmother: “Things like that, they’re what you need. That’s the kind of work that’s good for you.” The final scene in the film shows Maya in a car, looking pensive, on her way to the airport to fly back to the UK. The film ends with large graphics of the title in Tamil, which is an expression of Maya’s transmodern unconscious.

Maya clearly took her grandmother’s advice to task, and ended up becoming a music celebrity within a couple of years. This scene is very powerful in terms of its authenticity, and it functions as an organic plot twist that comes at the very end of the film to inform whatever took place before that moment, which is akin to Lacan’s concept of the “retroactive effect.”[46] From watching footage of young Maya, we knew she loved music and dancing, but she only started thinking of herself as a music producer after that paradigm-shifting conversation she had with her grandmother, which was candidly captured by Maya. These organic moments are rare in cinema, for they are the stuff of magic; however, the film is replete with them and this excess is surplus-jouissance.

The film has a non-linear structure because Steve Loveridge cuts back and forth between different spacetimes—e.g., London (1996), Sri Lanka (2001), London (2016), India (2004), Coachella (2005), India (2007), Los Angeles (2009), and London (2012). Bohemian Rhapsody, conversely, uses a lot of crosscutting and fast-paced montage sequences of Queen performing live superimposed with graphic titles of numerous city names to make the chronological unfolding of events more exciting in an artificial manner. Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. comprises an assemblage of original footage, archival footage, home videos, and Maya’s videos (the bulk of the material)—for this reason, I consider Maya the uncredited co-director of the film. The documentary’s overall style is a bricolage of cinéma vérité, confessional cinema, and proto-vlogging. The effect of this bricolage on the spectator is an enjoyment of Maya’s complex subjectivity through an equally enjoyable and intricate narrative structure, which also functions as a history of video camera technologies: the various image qualities they produced along with their diverse aspect ratios, for example.

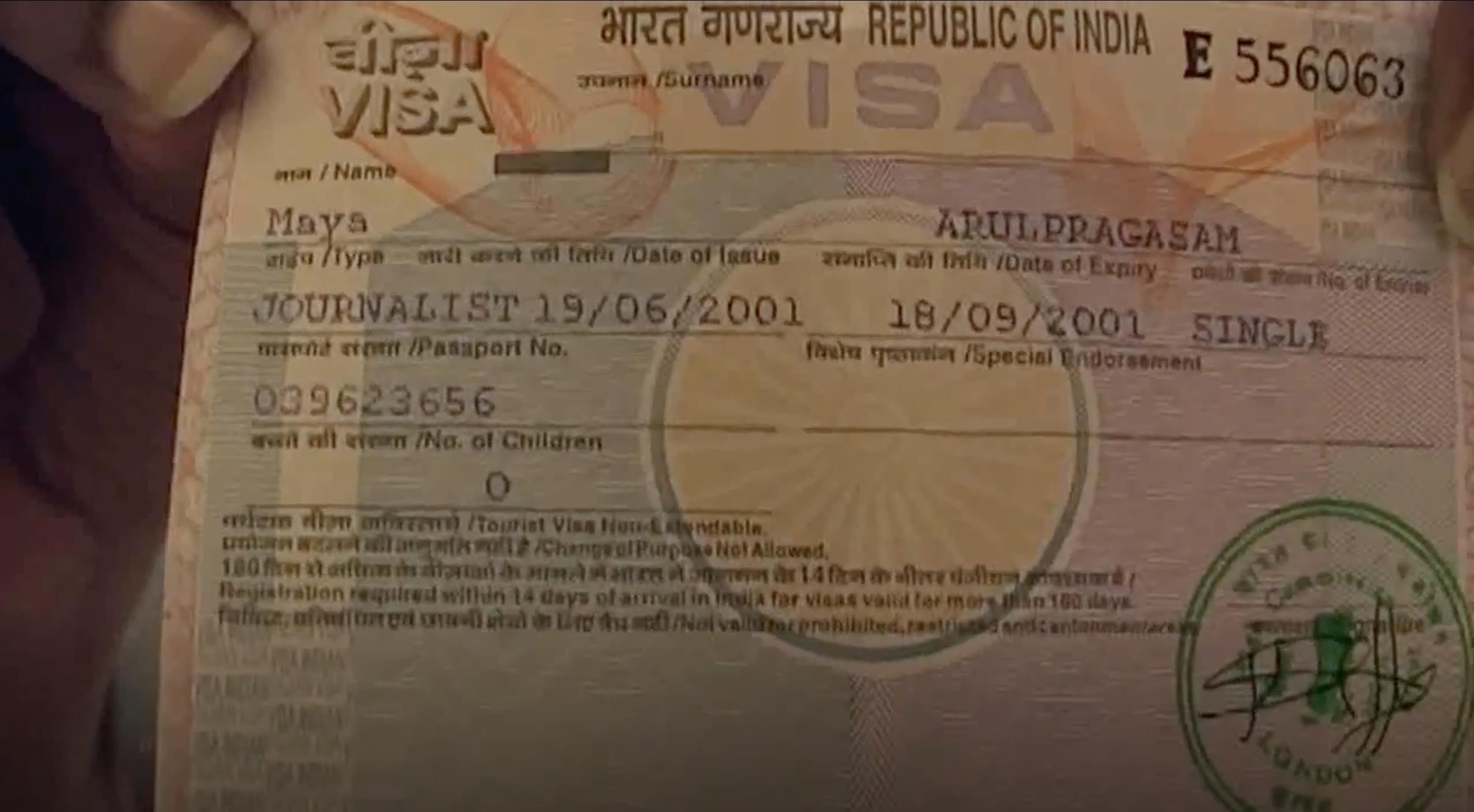

Loveridge and Maya are colleagues from Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, where they both received their undergraduate degrees in Fine Art. There is footage of both of them, shot by Maya, in 1996 wherein they are amateurishly experimenting with video, which constitutes the early scenes in the film. Loveridge’s friendship with Maya facilitated the film’s personal and authentic style, and also helped Maya trust him with the subject matter (her life). For instance, there are extreme close up shots of Maya’s student ID (1996) as well as her visa to Sri Lanka (2001).

Maya was born in 1975 and she grew up in Sri Lanka, but her family immigrated to the UK as refugees in 1985 to escape the Sri Lankan Civil War (similar to how Freddie and his family fled the Zanzibar Revolution in 1964). Maya, along with her sister (Kali) and brother (Sugu), grew up without really seeing their father (Arul) because he is the founder of the Tamil Resistance Movement. According to Arul, he trained all of the leadership of the Tamil Tigers.

What we did not get in Bohemian Rhapsody, we get here: a tell-all and complex story about a refugee becoming a celebrity. Even though Maya’s story may seem transparent, it is actually “opaque,” which does not mean that it is obscure.[47] It just means that many of the film’s spectators will never really understand, and should not be expected to understand, Maya’s experiences (e.g., the trauma of living through a civil war). Understanding is an Imaginary phenomenon because it involves imagining what the other person means. The alternative is to align our desires with Maya’s (i.e., in solidarity with the struggle of immigrants, for example) and to masochistically enjoy the traumatic Real (e.g., being out of place), which is best captured by the music video for “Borders.”[48]

The “Borders” video deals with the refugee crisis. It shows the refugees gazing at us (the spectators), which causes us to feel anxious because they are essentially questioning the indifference of our desire as well as our paradoxical enjoyment. In the film, we see Maya masterfully commanding the film set in India. For example, we see her with a walkie talkie, from a low angle, sitting on a camera crane and being lifted up, like a goddess, to the clear blue sky—not mentioning that she is acting in her music video, which she is also directing and funding with her own money since no one else had the courage to produce it for her.

She tells Loveridge, “I need to keep the immigrant story in all my work always because that is what I’m trying to make sense of.” Maya then adds, “We’re used as a scapegoat for Brexit. We’re used as a scapegoat to build a wall. But people have always mixed, and mingled, and moved. And interesting things happen because of it.” The “immigrant story” is the world of desire; it is why there is a refugee crisis in the first place because immigrants desire a better life. This is their desire, but it is also the desire of many of us (spectators); for example, think of the myth of the American Dream in this country. However, we also know that this desire does not necessarily realize itself through empirical objects. In fact, the realization of desire is always disappointing because we want more or something else.[49] And that is precisely how fantasy sustains desire.

The world of fantasy in the film is not seamless for it is constantly interrupted by Real deadlocks. For instance, when the Sri Lankan Civil War escalated in 2009, Maya went on several news programs to discuss the extrajudicial killings of Tamils by the army, she said this to Tavis Smiley: “under the guise of fighting terrorism, there’s a genocide going on.” She then goes on The Real Time with Bill Maher to continue speaking against the genocide, and Maher ends up dismissing her and making fun of her cockney accent. Because Maya felt dismissed and censored by the US media, she responded with a music video for her song “Born Free,” wherein ginger people are killed systemically and brutally for no apparent reason. The gruesome video got banned from YouTube, and it sparked an outrage on social media, which confirmed her point: that many people in Euro-America care more about a controversial music video, and consider it more traumatic than Real execution videos, which is obviously a form of denial.

These examples illustrate the silencing and dismissal, or repression, of critical voices (especially from ‘Brown’ bodies) in mainstream media spaces, which are dominated by uncritical voices. Supporters of the Sri Lankan government went further by labeling Maya a “terrorist” using the following signifying chain, as pointed out by Maya in the film: M.I.A. → Tamil → terrorist. In the next scene in the film, Maya accepts to do an interview with Lynn Hirschberg (an editor at the NY Times Magazine). Hirschberg watches the banned music video and calls it “brilliant” but then writes a hit piece about Maya in 2010, wherein she frames her as a vain celebrity: “‘I kind of want to be an outside,’ she [Maya] said, eating a truffle-flavored French fry.” Hirschberg, of course, fails to mention that she is the one who ordered the fries.

A third key deadlock in the film, wherein the Real of racism cuts through the fantasy of pop stardom is when Maya performs with Madonna and Nicki Minaj in 2012 at the Super Bowl halftime show and flips off the camera (the NFL). The US media hysterically overreacted to that moment according to the unconscious logic that dissenting ‘Brown’ bodies must be policed (cf. Colin Kaepernick). For example, on FOX, a ‘White’ female host says the following on her show, “And she [Madonna] chooses M.I.A.? Not even an American?” Immediately, her guests start laughing maniacally. Everyone knows that flipping off is as American as the NFL; however, it is only controversial when a ‘Brown’ woman performs the gesture, which is a form of expression protected by the US Constitution, whether we approve of it morally or not.

The Real of xenophobia and racism went further since the NFL demanded from Maya around 16 million dollars. To which Maya said: “I was sent to screen for approximately 15 seconds. And they want 15 million for it. It’s worse than being a murderer. A brown person standing up there who is not sucking dick is more offensive than murdering someone.” But why did she do it? It was a decolonial act of resistance in response to how some ‘White’ men associated with the NFL were demeaningly treating Madonna backstage.

My wife and I have come up with what we call “the 10-minute rule.” If we watch a film, and it does not cause our desire in the first 10 minutes, we switch to a more enjoyable film. In the second scene in Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., we see her directing the music video for “Borders.” We also hear her giving directions to her cast and crew in Tamil (a transmodern language). At some point, Loveridge interviews her asking: “Why are you a problematic popstar. Why don’t you just—” Maya: “Shut up. Why don’t you just shut up and get a hit?” Loveridge: “Yeah, why don’t you?” After a moment of silence, Maya responds: “If I shut up and get a hit. I would have to become a drug addict and overdose or like make a very bad ending to the story because that’s what happens when you don’t express the shit you need to express.” Loveridge: “Seriously?” Maya: “I came to music as a medium to express myself but the need to express myself through anything existed before.”

I read Maya speaking to Freddie here as a: fellow artist, (post)colonial ‘Brown’ subject, and South Asian immigrant from an ethnic minority. The difference between them is that Freddie thought that colonial assimilation through whitening was the answer; however, it only made him suffer more because what is repressed (queer) needs to be expressed (Queen). Contrastingly, Maya treads the path of decolonial pluralism as is evident from her words in the film: “As a first generation person, I left for a war, came as a refugee, that is now a pop star. What are the goal posts? It’s amazing that in one lifetime you have to come, and figure out so many things. But I’ve made it all fit together.”

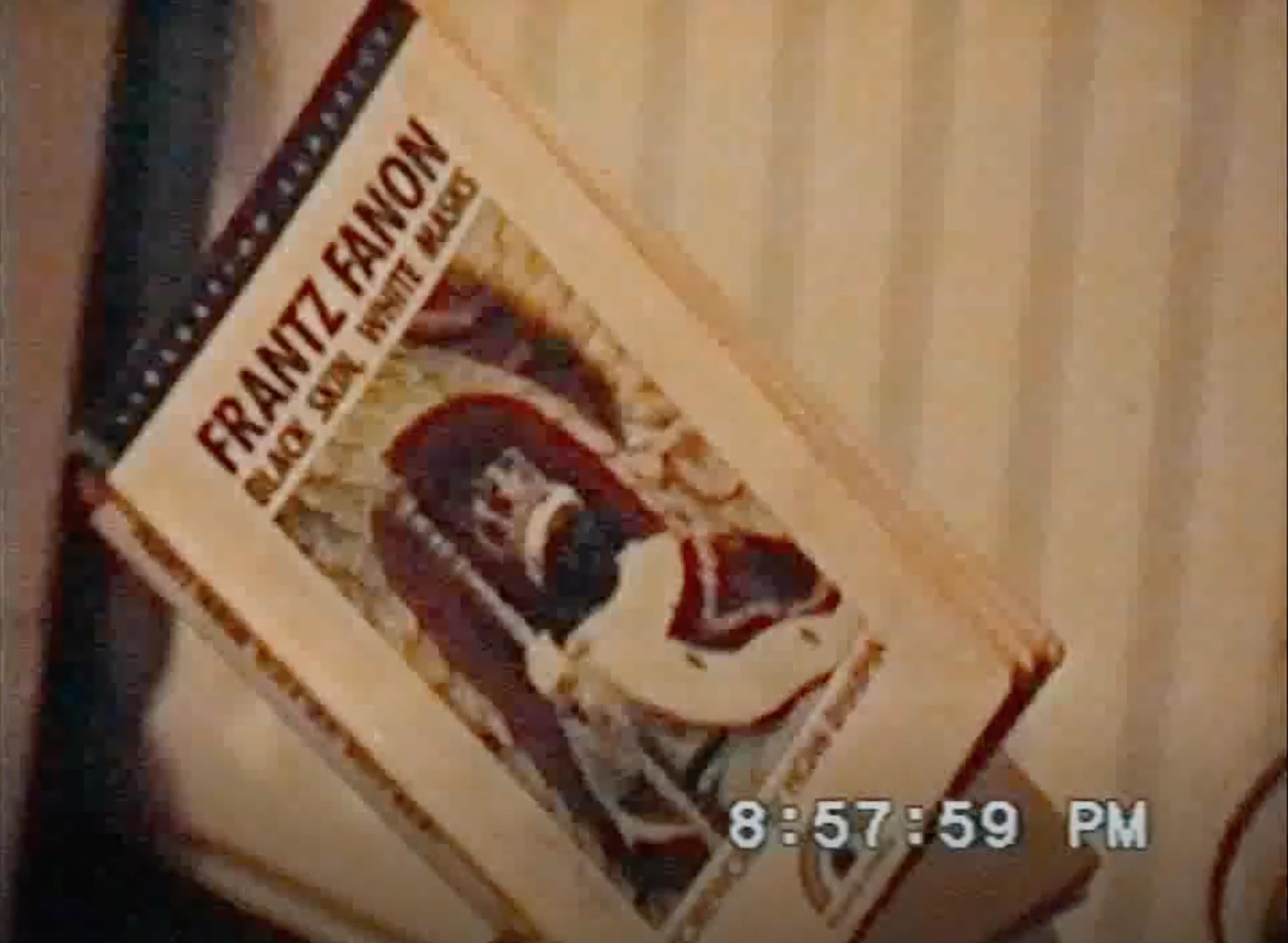

A masterpiece can still be made about Freddie, one titled Farrokh/Freddie/Queen. Here are Maya’s words from the first 10 minutes of Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., they can guide the narrative structuration of a yet-be-made masterpiece about Freddie’s life: “Music was my medicine. I had to deal with the fact that I was something else and I was different, and I was an immigrant. One day, in Sri Lanka [or Zanzibar], I was being shot at for being Tamil [or Parsee]. Then I came to England, I was getting spat at for being a Paki.” To illustrate my 10-minute rule, Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. immediately mesmerized me when I saw a 21-year old Maya reading a library copy of Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks 8 minutes into the film.

Another enjoyable moment in the film sheds light on the video camera as a companion or as a form of therapy. Maya was friends with Justine Frischmann, the lead singer of Britpop band, Elastica, and Frischmann invited Maya to go on tour with the band as their videographer. However, there is a scene of Maya, in an overexposed white bathroom, making a confession to the camera while going through a nervous breakdown. In tears, Maya speaks directly to the camera (the hypothetical spectator/listener): “I just wish I had someone to talk to right now. And I guess that’s why I’m stuck with my camera, because I just need to talk and get this shit out of the way...You know, I’m so pissed off. At people not really taking me seriously and not really caring about what’s going on and I don’t even know if this is what I should be doing right now.” Cut to a scene in a hotel room with Justine, wherein Justine tells Maya: “You’re just fucked up ‘cause you didn’t get enough attention.” Then later on, Justine prophetically tells Maya a couple of times: “You’re bigger than I am. I know you are.” The bathroom scene is powerful not only because it is authentic, but also because we see Maya’s desire for an audience manifest before our very eyes; in other words, we see the unconscious process that motivates someone like Maya to eventually become a famous artist. We also witness Justine recognizing that desire in Maya long before Maya had expressed any interest in making music. In fact, at one point in the film, Maya says that she always imagined herself writing songs for Justine, so she did not even fully realize her own potential until after her grandmother inspired her to sing.

Finally, there are a couple of shots where the camera is gazing back at us (the spectators), sometimes through some sort of reflection like a mirror or the lens of another camera. As McGowan writes: “The gaze is a distortion within the visual field, a point at which the seeming omnipotence of vision breaks down. In this sense, it is the reverse of the [spectators’] mastering look.”[50] The Gaze can also produce paranoiac knowledge because it is about how the film is seeing us while we are looking at it, which is anxiety provoking.

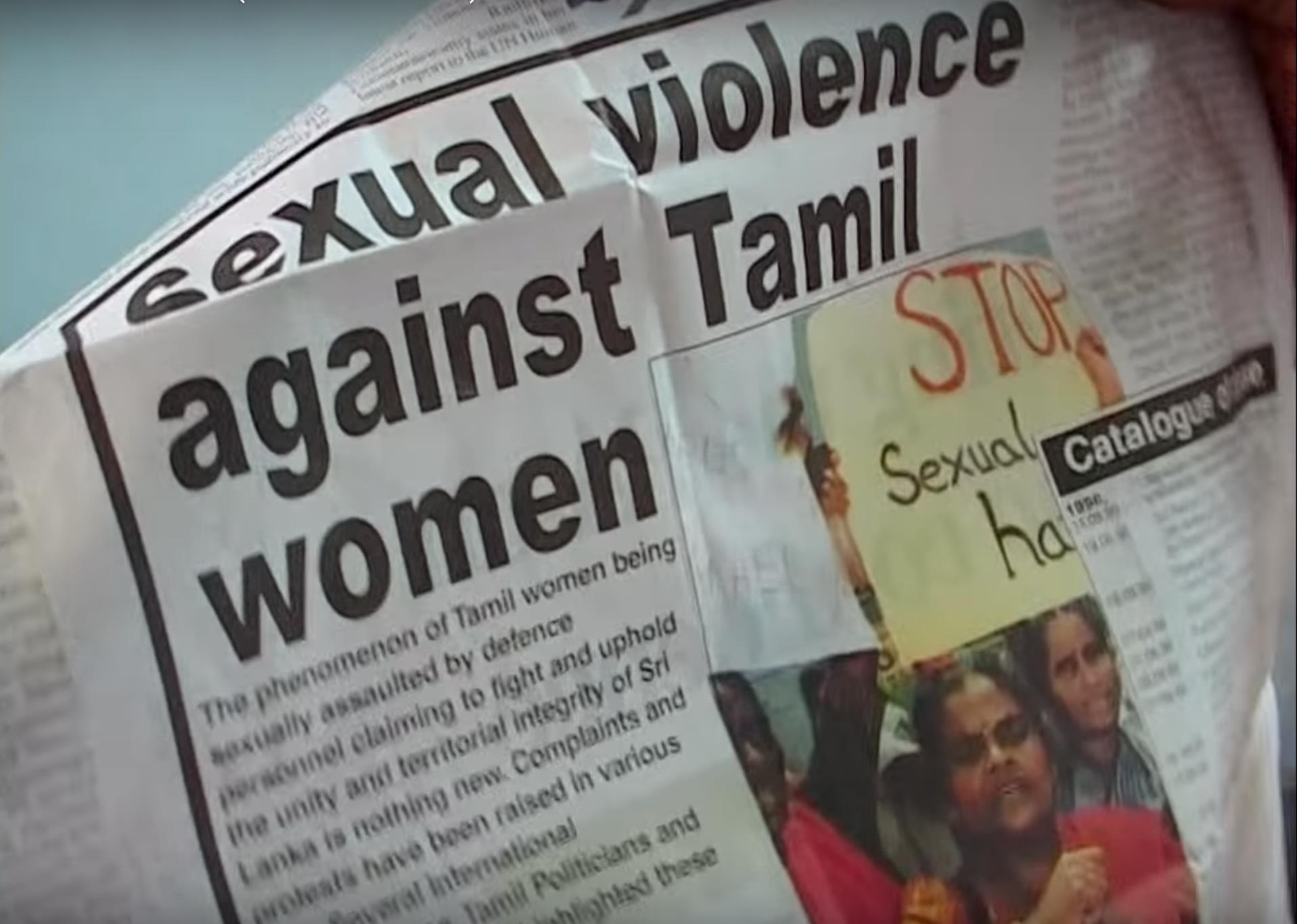

To put it in concrete terms, there is a scene during Maya’s stay in Sri Lanka, wherein she realizes that someone has been watching, or spying on, her for 45 minutes. Maya looks to her right and half of her face goes outside of the frame; the spontaneous framing and Maya’s organic performativity capture the essence of this terrifying moment. After reading an article about “sexual violence against Tamil women,” Maya looks around her nervously and then says: “I’ve got a feeling someone’s at my window, so I’m gonna just go and investigate.” She confirms her suspicion, and then tells an unnerving story entailing her and her mom (Kala) being on the bus and getting completely surrounded by soldiers who end up groping Maya, but she could not open her mouth because she was afraid of being dragged into the jungle, raped, and killed.

Maya then asks herself, “I was looking around, and I’m like, ‘Who do I ask for help?’ Like, ‘Who is that person?’ And there’s nobody else. So then you start looking out the window, going, ‘Somewhere, in that fucking jungle, there’s somebody who’s fighting for me.’” In the words of Desmond Tutu, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you [the spectator] have chosen the side of the oppressor.” This is the traumatic enjoyment inherent in Matangi/Maya/M.I.A.’s challenging Gaze to indifferent spectators, who have become desensitized to images of globalized violence and oppression in the mass media, such as the refugee crisis in Europe or the countless civil wars in the Global South.

Author Biography

Robert K. Beshara is the author of Decolonial Psychoanalysis: Towards Critical Islamophobia Studies (Routledge, 2019). He works as an Assistant Professor of Psychology and Humanities at Northern New Mexico College. For more information, please visit www.robertbeshara.com.

Notes

Bryan Singer and Dexter Fletcher, Bohemian Rhapsody (20th Century Fox, 2018).

Steve Loveridge, Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. (New York: Cinereach, 2018).

Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton University Press, 1997).

Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (Oxford: Blackwell, 1927/1962).

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007).

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 167, emphasis added.

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007).

David Lynch, Blue Velvet (De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, 1986).

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 92-93.

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 49-50.

Steven Spielberg, Schindler’s List (Universal Pictures, 1993).

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 15.

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 159.

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 163-65.

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 112.

Richard Roeper, “‘Bohemian Rhapsody’: Inept Freddie Mercury Bio is No Pleasure Cruise,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 31, 2018, https://chicago.suntimes.com/entertainment/bohemian-rhapsody-review-freddie-mercury-queen-rami-malek-richard-roeper/.

Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. by Bruce Fink (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1966/2006), 75-81.

Lesley-Ann Jones, Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury (New York: Touchstone, 2011), 340, emphasis added.

Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. by Bruce Fink (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1966/2006), 465.

Lesley-Ann Jones, Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury (New York: Touchstone, 2011), 209, emphasis in original.

Lesley-Ann Jones, Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury (New York: Touchstone, 2011), 192.

Ben Child, “Sacha Baron Cohen: I Quit Freddie Mercury Biopic After Dispute with Queen,” The Guardian, March 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/mar/09/sacha-baron-cohen-freddie-mercury-biopic-queen.

Sekhar Bhatia, “Freddie Mercury’s Family Tell of Singer’s Pride in his Asian Heritage,” The Telegraph, October 16, 2011, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/music-news/8828994/Freddie-Mercurys-family-tell-of-singers-pride-in-his-Asian-heritage.html.

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 75.

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 70.

Hans Holbein, “The Ambassadors” (The National Gallery, 1533), https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/hans-holbein-the-younger-the-ambassadors.

Aja Romano, “Bohemian Rhapsody Loves Freddie Mercury's Voice. It Fears His Queerness,” Vox, January 6, 2019, https://www.vox.com/2018/11/16/18071460/bohemian-rhapsody-queerphobia-celluloid-closet-aids, emphasis in original.

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Karnac Books, 1963/2004).

Jason Bailey, “51 Unforgettable Chris Rock Quotes for His 51st Birthday,” Flavorwire, February 6, 2016, http://flavorwire.com/559763/51-perfect-chris-rock-quotes-for-his-51st-birthday.

Thomas Flight, “Bohemian Rhapsody’s Terrible Editing - A Breakdown,” YouTube, March 14, 2019, https://youtu.be/4dn8Fd0TYek.

Alex French and Maximillian Potter, “‘Nobody Is Going to Believe You’,” The Atlantic, March 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/03/bryan-singers-accusers-speak-out/580462/.

Dave McNary, “Bryan Singer Will Get Directing Credit on ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’,” Variety, June 12, 2018, https://variety.com/2018/film/news/bryan-singer-directing-credit-bohemian-rhapsody-1202842535/.

David Ehrlich, “‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ Review: A Spirited Rami Malek Can’t Save Bryan Singer’s Royally Embarrassing Queen Biopic,” IndieWire, October 30, 2018, https://www.indiewire.com/2018/10/bohemian-rhapsody-review-rami-malek-1202014286/.

Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. by Bruce Fink (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1966/2006).

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 166.

Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. by Bruce Fink (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1966/2006), 711.

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 189-94.

Mathangi Arulpragasam, “M.I.A. - Borders (Official Music Video),” YouTube, 2016, https://youtu.be/r-Nw7HbaeWY.

Todd McGowan, Psychoanalytic Film Theory and The Rules of the Game (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).

Todd McGowan, The Real Gaze: Film Theory after Lacan (Albany: SUNY Press, 2007), 72.