“Our Common Community”: Third Way Cultural Work in Pleasantville and October Sky

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article argues that Pleasantville and October Sky perform the cultural work of the Clinton administration’s Third Way politics. Examining Clinton’s neoliberal policy work as well as the expansion of the memory industry in the 1990s, it contends that each film’s depiction of the past reveals more about the dominant ideology within the 90s.

Introduction

Gary Ross’s Pleasantville (1998) opens with the act of channel surfing. Flipping through a series of channels, the spectator beyond the frame eventually lands on “TV Time,” a channel devoted to sitcoms from the 1950s, which will soon have an all-day marathon of the eponymous classic, a sitcom “chocked full of pure family values, featuring the warm greeting, proper nutrition, and of course safe sex.” The marathon will afford an opportunity to “flash back to kinder, gentler times,” and so the contemporary spectator, historically and ironically detached, will presumably enjoy their engagement with a commodified version of the past. From the outset, then, Ross’s film unsettles the line between understanding and projecting onto bygone eras. In what follows, I investigate this blurry and porous distinction, looking at Pleasantville alongside Joe Johnston’s October Sky (1999). Drawing strength from Michel de Certeau’s insight that history’s intelligibility is refracted by the historian’s subject position, ideological beliefs, and methodology, I argue that each film’s depiction of the 50s reveals more about dominant sensibilities and political imperatives within the 1990s.[1]

Broadly speaking, the 90s witnessed a glut of historical and nostalgic films released by major studios. This cinematic fascination with the past aligns with broader market and sociopolitical forces of the period, pointing to what Andreas Huyssen calls the “hypertrophy of memory” that marked the end of the century.[2] With the American century coming to a close, filmmakers began to explore the past in earnest, and this tendency took shape alongside the dramatic expansion of the memory industry. The proliferation of public memorials and museums across the country transpired at the same time as camcorder and camera sales skyrocketed. The 90s also saw campaigns by the state to shape its constituents’ understanding of the recent past, particularly efforts to rationalize the failures and barbarism of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War. This confluence of a generalized desire to remember, the politicization of memory, and a highly profitable market of memory products suggests that popular media’s depictions of the past within the decade are neither innocent nor free from contemporary inflections. After all, the initial task for these cultural products was to appeal to audiences and consumers whose preoccupations and frames of reference were decidedly anchored in the 90s. Marita Sturken writes that “technologies of memory”—such as “public art, memorials, docudramas, television images, photographs”—cannot be divorced from “the power dynamics of memory’s production.”[3] Accordingly, historical or nostalgic studio films of the 90s are best understood as cultural products shaped by, as well as embedded with, sociopolitical concerns circulating during the time of their production and release.

This argument should come as no surprise to scholars familiar with the critical work on the relation of Cold War-era film to anticommunist politics. In Containment Culture, Alan Nadel reads Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956) as a biblical epic that “participat[es] in the same cultural narrative as American foreign policy.”[4] Alongside the biblical epics of the 50s, one could add western films to the list of popular representations of the past that symbolically capture the period’s generalized cultural anxieties. As Donald Pease points out, popular film “has acquired the power to dramatize fundamental shifts in the society’s self-representations. [. . .] The screen’s versions of the past have thereby been made to undergird the history of the present.”[5] According to Pease and Nadel, Cold War-era films about the past, particularly those released in the 50s, performed the cultural work of anticommunism, lending “symbolic efficacy” to state-induced fears of communist subversion and the related fantasy of America’s global mission to spread democracy.[6]

By contrast, the 90s was a period of transition for the nation. The collapse of the Soviet Empire in the 1980s put an end to the Cold War and established the U.S. as the bastion of free-market capitalism. American policymakers could no longer deploy anticommunist bromides, so a chief concern amongst them became the establishment of a new symbolic pact between the state and its constituents. This burden fell largely on the Clinton administration, which attempted to shepherd the nation into a new sociopolitical order, one that would leave the Cold War behind. What distinguished Clinton from previous Democratic leaders, however, was his espousal of “Third Way” politics, which combined multiculturalism and neoliberal policies. This contradiction between rhetorical celebrations of diversity and economic structures foreclosing the equalization of life chances benefited, I argue, from a symbolic apparatus that naturalized the sociopolitical order, an apparatus that popular films about the past provided.[7]

Both Pleasantville and October Sky provide an ostensible glimpse of late-50s America. This period was not only characterized by social conservatism but also by the structural reforms associated with Roosevelt’s New Deal. Yet these films traffic in themes and images that do not suggest historical fidelity so much as reflect the Clinton administration’s contradictory efforts to, on the one hand, coax the nation out of the past and, on the other, define the state’s relation to its constituents along neoliberal lines. De Certeau writes that “those who make history today seem to have lost the means of grasping a statement of meaning as their work’s objective, only to discover this statement in the process of their very activity. What disappears from the product appears once again in production.”[8] Historical discourse, in other words, bears the ideological imprint of its purveyors, and the site of its production has a determinative effect. Any analysis of such discourse requires an account of the period in which it was produced. As I aim to show, these films perform the cultural work of Third Way politics, remodeling the 50s in imitation of the 90s. They are, with or without intention, implicated in the workings of hegemony, promoting the normative desires and sensibilities abetted by the very neoliberal structures that have perpetuated class, gender, and racial inequality within America. A line of inquiry that views these films as such unlocks a better understanding of popular media’s conditions of possibility as well as its role in the discursive operations of power.

Beyond the similarity that Pleasantville and October Sky both flash back to the same period in American life, there are multiple reasons for bringing them together. First, they are both big-studio films—produced by New Line Cinema and Universal Pictures, respectively—which means they were released with a wide target audience in mind. That they both grossed more at the box office than their estimated production budget indicates that this audience was ultimately reached.[9] Second, the films’ main characters are played by actors who have gone on to have successful careers from a critical and commercial standpoint—in Pleasantville, Tobey Maguire and Reese Witherspoon; and in October Sky, Jake Gyllenhaal—so it is to be expected that these films will not be relegated to the dustbins of history anytime soon. The last, and somewhat paradoxical, reason for bringing these films together is that they offer two divergent strands of discussion, as each has an idiosyncratic relation to its historical source material. On the one hand, Pleasantville is self-reflexive and metafictional, in that it follows two teenagers from the 90s as they unsettle the repressive cultural mores of the eponymous sitcom world into which they are teleported, a suburban town perpetually stuck on the calendar year of 1958. On the other hand, October Sky is an earnest re-creation of Coalwood, West Virginia in the late 50s. The narrative, adapted from Homer H. Hickham’s memoir Rocket Boys (1996) by screenwriter Lewis Colick, follows the teenaged Homer (Gyllenhaal) and his friends as they pursue a future beyond their parochial mining town. Jim Collins writes that two discrete genres of films emerged in the 90s: “eclectic irony” and “new sincerity.” According to Collins, “ironic hybridization” marks the former genre, while the “pursuit of lost purity” marks the latter.[10] Respectively, Pleasantville and October Sky fit into these two categories; together, they provide coverage as well as an opportunity to discuss how each of these genres captures dominant ideological currents of the decade. I need to elaborate, then, on the Clinton administration’s Third Way politics and their connection to the hypertrophic memory of the decade.

Third Way Politics and Hypertrophic Memory

At the heart of Clinton’s Third Way politics was a combination of neoliberal economic policies and a cultural project predicated on the principle of inclusion and antidiscrimination. On July 16, 1992, he accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for president and outlined his aims for a new sociopolitical order. He announced that his presidency would mark the birth of a “New Covenant” in America—a quasi-religious pact between the state and its constituents that was to be about “our common community”:

Look beyond the stereotypes that blind us. We need each other—all of us—we need each other. We don’t have a person to waste, and yet for too long politicians have told the most of us that are doing all right that what’s really wrong with America is the rest of us—them. Them, the minorities. Them, the liberals. Them, the poor. Them, the homeless. Them, the people with disabilities. Them, the gays. [. . .] But this is America. There is no them. There is only us.[11]

He insisted on the togetherness of the American social body by first acknowledging several groups of citizens whom hegemonic discourses had stigmatized in the past. Clinton’s rhetorical negation of the negation was a call to transcend the widespread discrimination that marked the twentieth century, but it did not resonate alongside his economic agenda. The cultural project of cohesion espoused by Clinton would take shape in isolation from his administration’s neoliberal policies, which worked to abolish many of the social safety nets and redistributive apparatuses established by the New Deal. Primarily through business-friendly tax structures and welfare retrenchment, such policies diminished the labour force’s share of national wealth as well as transferred the burden of social security from the state to individuals and families, consequently facilitating wealth’s upward flight.[12] Pease points out that Clinton’s “embrace of a Third Way that transcended the ‘politics of difference’ enabled him to conceal the structural violence at work in his programmatic elimination of welfare state institutions in the name of market imperatives.”[13] By separating economics from culture, Clinton continued the policy work that divided the social body in the past.

Neoliberalism has always operated at the intersection of class and culture. As David Harvey points out, incipient neoliberal reform “appealed to the cultural nationalism of the white working classes and their besieged sense of moral righteousness”—an oft-sublimated form of bigotry that led many to support policies threatening their long-term wellbeing.[14] Indeed, no economic policy is implemented within a context cleansed of cultural hegemony and histories of dispossession. The Clinton administration’s dismantling of welfare institutions provides an illuminating example of the contradiction between neoliberal economics and multiculturalism on which Third Way politics pivot. Debates about welfare often exceed the issue of class and wealth redistribution, tending to animate mainstream cultural fears and stereotyped presuppositions about minority groups perceived to be “tax-eaters.” Lisa Duggan cautions against the rhetorical separation of identity and class politics, explaining that “welfare ‘reform’ has [. . .] depended, for its cultural effectiveness, on coded hierarchies of race, gender, and sexuality.”[15] The politics of redistribution have long constituted sites of class and cultural struggle; in order to register the violence of neoliberal reform, this overlap cannot be overlooked.

Clinton’s policy work dovetailed with his rationalization of past actions taken by the state—for instance, its militarism and imperial expansion throughout the twentieth century—through what Cathy Schlund-Vials calls Cold War “apologetics”: “Premised on a two-sided understanding of apology (as an expression and an excuse for problematic action), and rooted in argumentation (rhetoric), these apologetics seemingly reconcile (after the fact) the failures of US foreign policy by way of an ostensibly universal humanism and humanitarianism.”[16] Consider Clinton’s rhetorical movement from “them” to “us,” in which abstract universality eclipses the state’s history of barbarism and its uneven distribution of privilege. Given the depredations of global capitalism as well as the perennial divisions of the American social body, this rhetoric does not articulate social togetherness so much as maintain the innocence of the hegemonic American subject—white, male, heterosexual—who has ostensibly not benefited from structural inequalities at home and imperialist exploitation abroad. By overlooking the specific victims and beneficiaries of domestic and foreign violence throughout the Cold War, these apologetics render the decidedly shameful aspects of recent history moot and, in conjunction with neoliberal austerity, stifle the lessons of the past with complacency.[17]

That these apologetics coincided with an omnipresent desire to remember and record indicates that the period’s hypertrophic memory worked to make the past more consumable. As Huyssen argues, the unprecedented expansion of the memory market, replete with objects for remembering and recording, made it difficult to winnow out “usable pasts from disposable pasts.”[18] Hypertrophic memory compromises the collective capacity to learn and draw from the past while remaining oriented towards the future. The tromp l’œil here is that the past seems more democratic as memory, even though reification and fetishism are the cost of its wide availability. To be clear, it is not that memory or a focus on the past is inherently inimical to change. The celebration of marginalized histories, for instance, opposes cultural hegemony, and the public acknowledgement of such histories constitutes an important step towards redressing institutional wrongdoing. The overwhelming commodification of the past, however, fosters the accumulative desire to possess it, thereby directing attention away from ongoing structural violence. Viewed from this perspective, the memory boom of the 90s operated in a manner analogous to Clinton’s rhetorical dialectics, which underemphasized the role neoliberal policies play in conserving inequality.

The contemporaneousness of Cold War apologetics and hypertrophic memory bespeaks the practicability of approaching popular films about the past as cultural commodities that occlude the state’s perpetuation of cultural and class hierarchies with themes and images of putative progress. As a medium of what Guy Debord calls “the time of the spectacle”—which functions, “in the broadest sense, as the image of the consumption of time”—film is implicated in the process of capitalist abstraction that affixes value to, and therefore partially obscures, irreducibly complex and interrelated phenomena.[19] Pleasantville and October Sky, as such, perform Third Way cultural work, presenting infelicitous images of the past that distract from the Clinton administration’s conservative policies. The relationship between Third Way politics and the innocence of the hegemonic American subject preoccupies the following section, which looks more closely at Pleasantville.

“It’s a question of values”: Pleasantville and the Hegemonic American Subject

In Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Fredric Jameson identifies in postmodern film a desire to understand the present through ironic engagement with stereotyped images of the past.[20] Pleasantville seems to have internalized this critique of contemporary culture’s inability to understand its own historicity without highlighting its iconoclastic relation to bygone eras. In fact, Ross’s film metafictionally foregrounds the limited and mediated nature of the present’s relation to the past. The film follows twins David (Tobey Maguire) and Jennifer (Reese Witherspoon) as they literally enter the world of a popular sitcom from the 1950s—becoming Bud and Mary Sue, respectively—and subsequently undermine the eponymous town’s parochialism and superficial ethic of pleasantness. Making clear that the television set frames their access to the 50s, the film self-consciously rejects verisimilitude and underscores its reduction of the past to a series of stereotypes. In so doing, though, it treats the 50s as a fantasmatic lifeworld in which the normative American subject, principally represented by David/Bud, can function as a progressive agent of change without relinquishing their hegemony. Accordingly, the film moves in step with Third Way politics and their fundamental contradiction between progressivism and conservatism.

The tendency to separate multiculturalism from the material inequalities that sustain white-male hegemony seems to have inflected critical readings of Pleasantville. Paul Grainge, for instance, situates the film’s themes within the context of the 90s culture-war debates, debates that pitted liberal multiculturalists against neoconservatives; focusing on Ross’s use of chromatics as a metonymic register of progress, he argues that the film “satirizes the fallacious nostalgia of the New Right, attached as it was (and remains) to a prelapsarian order of patriarchal norms and family idealism.”[21] In this reading, David and Jennifer “become the figurative embodiments” of 1960s radicals, the bête noire of neoconservatives who viewed the countercultural movements of the 60s as the source of contemporary anomie.[22] Yet such movements were not wholly unproblematic, as the fetishization of black culture amongst privileged whites bespoke the relative security of their social position and created new profit-making opportunities for capital.[23] Trading on the symbolism of 60s counterculture is also a form of nostalgia, one that obfuscates “how neoconservatives and liberal multiculturalists share an antagonism to redistribution.”[24] This section’s subsequent analysis shows how the film toes the liberal-multiculturalist line; by recasting the materially secure twins as cultural outsiders within the sitcom world, it paints a tenuous picture of diversity in a period (the 90s) marked by the exacerbation of class inequality and the perpetuation of white-male dominance.

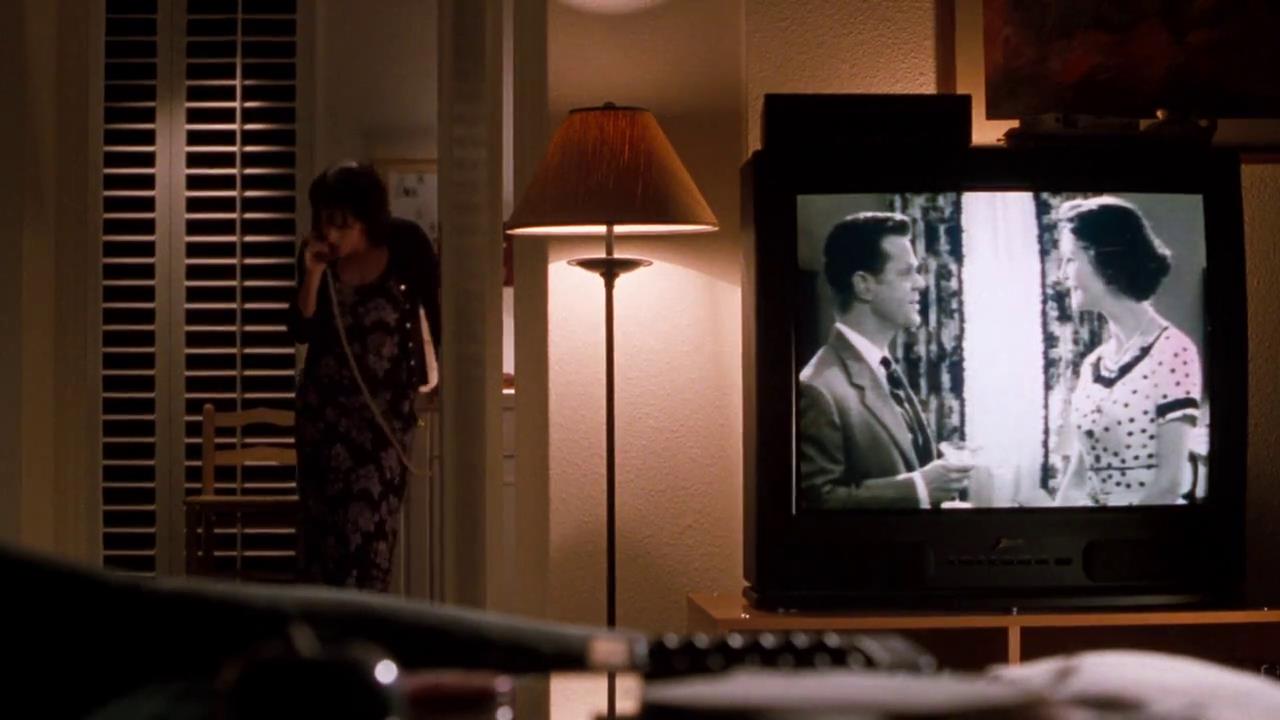

Not long after the aforementioned opening sequence, the film provides explicit clues as to the sitcom’s nostalgic appeal for David, who can quote episodes verbatim. A series of dolly shots moving down the aisle of high-school classrooms frames teachers warning their classes about vanishing job opportunities, the chances of contracting HIV, and the catastrophic consequences of global warming. Yet the film conjures up these threats no sooner than it minimizes them, immediately cutting to a security vehicle patrolling David and Jennifer’s relatively affluent neighborhood. It seems that their socioeconomic position will insulate them from the worst of these contemporary problems, and so the brief allusion to crises exacerbated by economic systems registers as humor and has no bearing on the rest of the narrative. The film keeps its focus myopic, emphasizing the personal and domestic as the true sources of David’s nostalgic longing. In the next series of shots, one frames him, in the foreground, watching the sitcom while, framed by the kitchen doorway, his mother (Jane Kaczmarek) argues with her ex-husband through the phone. The spatial juxtaposition of the television set with the doorway intensifies the thematic juxtaposition of the sitcom’s familial bliss with real familial dysfunction. David dispels any doubt as to which scene he prefers by increasing the volume and anticipating a line his sitcom mother, Betty Parker (Joan Allen), will utter: “What’s a mother to do?” This sequence inverts fantasy’s relation to reality, thereby reducing the latter to a distraction from the much more engrossing world of the sitcom. It also establishes the sitcom as a kind of object of desire for David, one that promises the fulfillment his real life lacks.

When David and Jennifer come to magically inhabit the sitcom world, he voices a reluctance to disrupt the eponymous town’s status quo. Yet the superficiality of his fantasmatic refuge soon becomes evident; he and Jennifer/Mary Sue discover that the town’s unchanging perfection depends on repression and blind acceptance, as the books contain no words, the school teaches a “non-changeist” curriculum, the music is of a “pleasant and temperate nature,” the residents only sleep on twin beds, and they only express their sexuality by holding hands. The town’s mayor, Big Bob (J.T. Walsh), is the exemplary embodiment of the town’s specious ethic of pleasantness. A canted low-angle shot, indicating an insidious aspect to his political position, frames his first appearance in the narrative, when he enters the barbershop. He immediately displaces the customer getting his hair cut, telling him without irony, “I couldn’t possibly take your spot.” Later, when the angry male patriarchs of the town discuss a plan to maintain their hegemony, he tells them, “It’s a question of values.” Yet by this point in the narrative, his appeal to social norms sounds hollow and retrograde. Through his leadership of this reactionary movement, coupled with repeated shots of him alone on a dais, talking down to people, and gesturing authoritatively, the film establishes Bob as a kind of fascist figure whose resistance to change is overwhelmed by his constituents’ willingness to eschew convention.

The film initially articulates such willingness to an emergent female sexuality. The primary agent of change is Jennifer/Mary Sue, as she displayed no attachment to the sitcom world prior to inhabiting it. Consequently, she flouts the conventions regulating fashion and brazenly violates the prohibition against intimacy, inaugurating a kind of sexual awakening in the town after she fornicates with her boyfriend, Skip (Paul Walker). Her transgressions animate the chromatic revolution in the sitcom world, as the first sign of color, a red rose, appears when Skip drops her off at home. Later, in an inversion of the typical mother-daughter relationship, she teaches Betty about sex and autoeroticism, as the latter has begun to feel the emptiness of her marriage after a fortuitous reunion with the diner counterman, Bill Johnson (Jeff Daniels). This scene’s comedic capital is fully realized when Betty pleasures herself in the bathroom. The floral designs on the wall—and even the bird perched on a branch outside the window—appear in color as she reaches climax, at which point the film cuts to an exterior shot that frames the tree on the Parkers’ front lawn bursting into bright flames, a clear metaphorical allusion. However, the film is quick to sublimate this eruption of sexuality into a cultural object produced by a male character: when Betty and Bill Johnson begin their affair, he paints a mural of her naked body in vibrant color, a mural whose public display galvanizes opposition from conservative townsfolk.

In fact, the film’s use of color to register its characters’ transformations betrays a conservative agenda. Near the midpoint of the film, Jennifer/Mary Sue wonders why the women around her continue to become “colored” (an unsubtle reference to midcentury racial tension that I discuss more fully below), even though she has had “ten times as much sex as the rest of these girls”—to which David/Bud responds, “Maybe it’s not just the sex.” Ironically, as the main force that loosened the town’s puritanical sexuality, Jennifer/Mary Sue must begin to tame her, as she puts it, “slutty” sexuality in order to become colored. She sacrifices nights out with Skip for nights at home with a book, and in another example of sublimation, the film shows her reading D.H. Lawrence, whose erotically charged work seems to offer a means of libidinal release and intellectual stimulation at once. While Jennifer/Mary Sue’s pursuit of academic goals is not altogether conservative or problematic, her trajectory strips her of the rebellious energy she initially mobilized to agitate the town’s public sphere and consigns her to the domestic sphere, a private space that the film assiduously aligns with unhappy women.

Cementing her transformation, at the end of the film, she chooses to stay in the sitcom world and attend college rather than return to the present with David. Her poor grades, she rationalizes, will preclude her from attending college in the 90s, but her decision to stay in the past will also subject her to the gender inequalities that structured universities and the country in the late 50s (inequalities that also prevailed, although to a much lesser extent, in the 90s). Indeed, the pact among the state, business, and labour fueled economic growth in the postwar period, but it also pivoted on the Fordist family wage that imposed heteropatriarchal protocols on families and severely limited women’s earning potential. Melinda Cooper points out that the Fordist family wage “was inseparable from the imperative of sexual normativity.”[25] Perhaps Jennifer/Mary Sue will have a chance to partake in second-wave feminist movements, fighting for the very freedoms she inherited, but her growth and final decision reestablish the gendered hierarchy the film ostensibly sought to undermine at the outset. The focus on normative sexual activity, unrepressed but neither excessive nor non-heterosexual, and consumer choice as indices of progress from sexual abstention and standardized consumption helps to obscure this conservative inflection to Jennifer’s development.[26]

Pleasantville thus follows thematically in the footsteps of Clinton’s apologetics that, in subsuming “them” under the category of “us,” worked to preserve the innocence of the hegemonic American subject at the end of the Cold War. The course of David’s growth brings this point into sharp relief. In the opening sequences, David is introduced with a trick. Mediated by the convention of shot-reverse-shot dialogue, he looks to be talking to a female classmate; he subsequently asks her out on a date, to which she responds with laughter and a smile. But then a wide-angle shot reveals David at a considerable distance from her. In actuality, he has just delivered a soliloquy with his male gaze trained on a female target who is neither available nor interested. Rather, she is engaged in conversation with another male classmate, whose sleeveless hoodie and coiffed hair stand in sharp contrast to David’s loose t-shirt and messy hair. Here, the film limits its expression of masculine difference to personal style, as both characters are indistinguishable along racial and class lines. Establishing a narrow framework for understanding social heterogeneity, this introductory moment of emasculation intimates that, once teleported into the sitcom world, David is to become an agent of social and romantic open-mindedness—so that the “hopelessly geek-ridden,” as Jennifer calls him at one point, can stand on equal footing with the physically prepossessing.

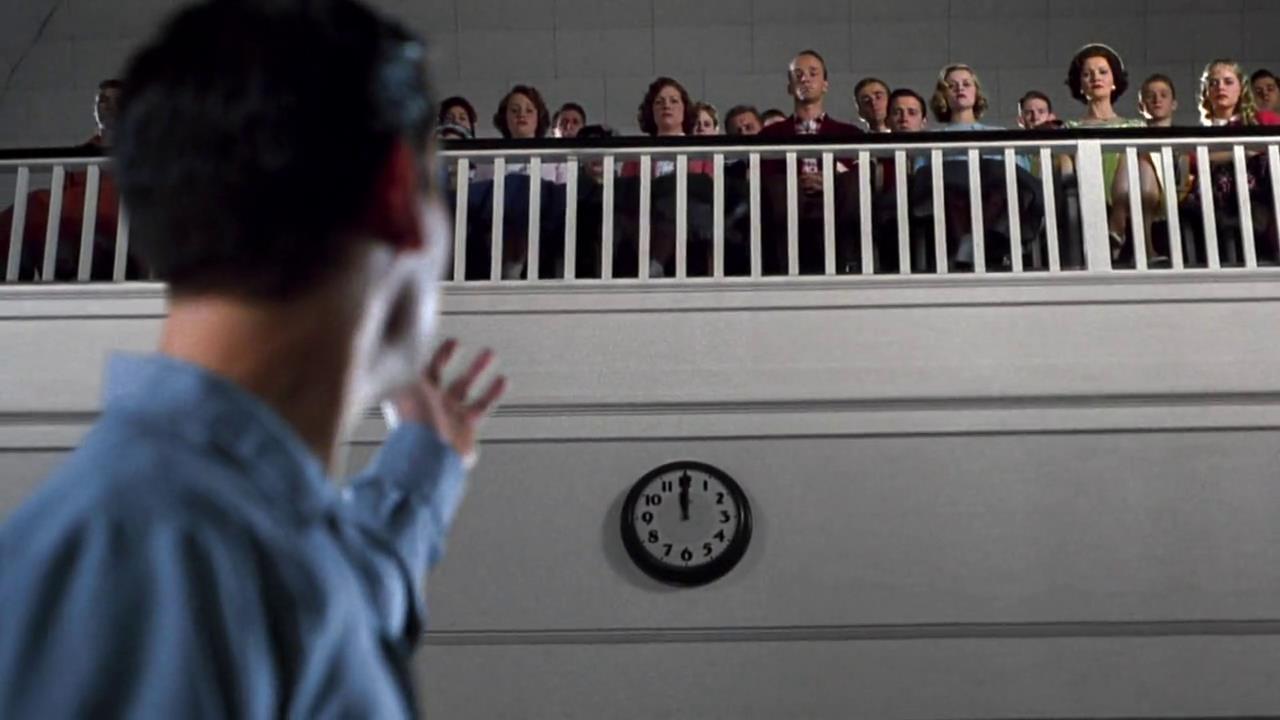

Accordingly, David/Bud’s chromatic transformation occurs when he protects the colored Betty from a mob of black-and-white teenagers. In this moment of transformation, David/Bud becomes the ideal version of himself that eluded him at the beginning of the film. With his subsequent courtroom speech, he becomes the voice of the revolution, giving the coloreds their decisive cultural and moral victory over the conservatives. Only by entering his fantasmatic refuge, then, can David attain the fullest expression of his individuality and foster social change. Yet the courtroom scene, while clearly displaying the town’s segregation along chromatic lines, upholds a traditional gender dichotomy that associates men with the public sphere, as Jennifer/Mary Sue and Betty passively watch him deliver his defense. The scene underscores that David’s self-reinvention and the colored victory coextend. By placing him in a custodial position vis-à-vis sexual and social freedom in the 50s, albeit a self-consciously mediated version of this decade, the film leaves his privilege untouched and its historical underpinnings unexamined. His trajectory from dissatisfied teenager of the 90s to leader of the counterculture within the 50s sitcom world allegorizes the Clinton administration’s sociopolitical agenda, a trajectory of character development that dehistoricizes white-male hegemony.

David subsequently returns to the 90s with a new outlook governing his conduct. Just as he saved his sitcom mother, so too does he soften his real mother’s emotional distress. As she tearfully rues the current state of her life, he says, “There is no right house. There is no right car. [. . .] [Life’s] not supposed to be anything.” Here, he demonstrates the ethic of open-mindedness he has adopted. His advice resonates because the struggle in the eponymous town was not just about sexual expression; as mentioned above, it was also about consumer choice, with the colored characters opting for different music, different beds, and different clothes. Recall, moreover, that the film initially expresses a hierarchy of masculinity through style. Pleasantville, that is, seems incapable of articulating its lesson of freedom and choice without symbols of commodity culture. It inscribes the market as the most meaningful site in which to explore diversity, presenting a vision of tolerance undisturbed by class and racial difference. This consumer-oriented vision parallels the Clinton administration’s subordination of the welfare state to market imperatives. The implication is that, while there is no right house and no right car, having a car and a house means life will amount to something irreducible and unique.[27]

Consumer choice can only serve as a weak, and ultimately misleading, synecdoche of diversity tout court. Such myopia fails to see the ways in which market-friendly governance conserves inequality. From this perspective, the film’s treatment of “gender and chromatics as an unstable allegory of racial difference” resembles an aesthetic strategy serving 90s hegemony.[28] As Greg Dickinson points out, even though the depiction of the conservative movement against the coloreds alludes to actual anti-black racism in midcentury America, “these racialized possibilities always remain screened as the characters become colorized versions of whiteness.”[29] The film’s suggestion of a symbolic alliance between oppressed blacks and repressed whites puts under erasure the specificity, and persistence, of physical and institutional violence against black people, treating the past, in Sharon Willis’s words, as a fantasy “where white people were largely innocent and well-intentioned.”[30] Such a fantasmatic occlusion of historical injury reflects the contradictory initiatives of Third Way politics, which condemned discrimination while leaving white-male hegemony unquestioned and intact.

October Sky’s Neoliberal Swerve

Adapted from Homer H. Hickham’s memoir, Joe Johnston’s October Sky has a much different relation to the past than Pleasantville. By depicting Coalwood, West Virginia in the late 50s, the film is ostensibly faithful to Hickham’s memoir. And while cutting two of Hickham’s close friends out of the narrative, it nevertheless tracks his and his friends’ trajectory from hopeless rocket enthusiasts to amateur rocket engineers. Yet the temporal limitations and aesthetic imperatives of popular film limit its capacity to remain faithful to its literary source material. Consequently, a good deal of the memoir has been excised and altered through adaptation. This section attends to the way in which specific cuts and changes, alongside different points of emphasis, give the film a neoliberal cast, one that resonates more with popular sensibilities in the 90s than in the 50s. In particular, the film fails to register the context of morally ambiguous capital-labor relations in which the boys’ teenage lives actually unfolded—a situation that Hickham’s memoir delineates with much detail. Instead, the film reduces the complexity of time and place to melodrama, aligning union activity with greed and indolence as well as portraying Homer’s trials and eventual success in terms of a dialectical struggle between father and son.[31] Such infidelity recalls Harold Bloom’s notion of the “clinamen,” the “swerve” by which the artist brings a “corrective movement” to bear on their predecessor’s work.[32] Johnston’s film, that is to say, can be distinguished from its source text not simply by its modal dissimilarity but by its neoliberal swerve.

In sharp contrast to Pleasantville, whose opening sequence underscores its presentist tenor, October Sky’s opening establishes its late-50s setting by interlacing shots of coalminers descending below ground with ones of townsfolk listening to the radio, which informs them that the Soviets have launched Sputnik 1, the first manmade satellite to orbit Earth. The Soviet success, the radio announcer says, marks “a grim new chapter in the Cold War.” Despite this allusion, the content of these shots signals the film’s narrow focus. The images of coalminers marching to work, carrying lunch pails, and crowding into a mine-bound lift draw attention to local problems and pressures. Cold War political activity, this opening conveys, exists solely on the radio for the people of Coalwood, and conflict will issue not from a desire to contain external threats, a popular kind of narrative in the 50s, but from a desire to escape containment. The tension here between underground labour and supra-planetary aspiration points less to Russia-U.S. one-upmanship than to the difficulty of building a life beyond town limits. It foreshadows the resistance Homer and his friends, hoping to parlay their amateur rocket making into scholarships, will meet in a town that survives on the productivity of its coalmine. This opening makes clear that the film is to be about upward mobility. For the boys—aside from Homer, Roy Lee (William Lee Scott), O’Dell (Chad Lindberg), and Quentin (Chris Owen)—coalmining is an existential threat, and building rockets offers the possibility of avoiding such an occupation.

To that end, the film builds to a final crescendo through a series of small successes and setbacks, ultimately affixing its vision of class mobility to a theme of individualist striving. The boys build a rocket, fail, build another, and fail again, before finally becoming dab hands at amateur rocket building. Their eventual success at the national science fair is the product of tireless effort, securing them academic scholarships and a way out of Coalwood (a departure from Hickham’s memoir to which I return below). Along the way, an intergenerational struggle unfolds between Homer and John (Chris Cooper), his father as well as the foreman at the coalmine. Yet towards the end, the father-son dialectic comes to a melodramatic resolution, as Homer tells his father, “I got it in me to be somebody in this world, and it’s not because I’m so different from you either. It’s ‘cause I’m the same.” Here, the first-person pronoun negates the negation, evoking the American dream of self-invention. Father and son no longer stand apart—with the former’s localist complacency opposing the latter’s upward ambition—but together as individuals, their generational differences extenuated at last. Subsequently, in the final scene, they watch one of Homer’s rockets soar beyond the clouds, John’s arm wrapped around Homer’s shoulder—from which shot the film cuts to a space shuttle launching from Cape Canaveral. An American flag flaps in the breeze as onlookers celebrate the shuttle ascending into space. This closing stamps a moral of individualism on the narrative; through the juxtaposition of the two launches, the film moves from the local to the national stage, allegorizing Homer’s upward flight from his working-class provenance. The implication is that climbing the social ladder is no more Homer’s dream than an American one. Homer is but one of many possible referents for American individuality.[33]

Yet the fact that the shuttle launching from Cape Canaveral was funded by taxpayer money complicates this individualist ethic. Keeping this point in mind displaces some of the thematic weight given to the closing juxtaposition, enabling a reading that identifies the film’s ending not as a triumph of willpower over de-individualizing parochialism but as something slightly different, yet whose difference is nevertheless important: a triumph of the individual who benefits from fiscal policy. Such a reading yields the observation that individual success depends on political forces channeling the flow of national resources in a specific direction. It would seem that no upward flight, be it towards space or up the social ladder, is possible without a collective apparatus subsidizing the trip. Tax structures are omnipresent and therefore not generally worth mentioning, but this reading shifts focus from what the film makes available to audience perception to what remains obscure. It is helpful to point out here that, while the neoliberal state makes class mobility an atomistic affair through market-friendly governance, such policy work had yet to take shape in the 50s.[34] For most (white-male) social climbers of the period, upward mobility could not be conceived outside of the New Deal programs, welfare apparatuses, and fiscal policies shaping the social order. Indeed, while the film attributes the boys’ rise to scholarships won through hard work, their trajectory takes shape differently in Hickham’s memoir; instead, some of them joined the Air Force and “would use the GI Bill for college.” “In a more perfect world,” Hickham writes, “we would have all gotten scholarships because of our win [at the national science fair]. It didn’t happen.”[35] In actuality, the world is not perfect, and Hickham makes clear that upward mobility required further sacrifice from his friends, as well as a final boost from a program of collective investment.

Along similar lines, what further distinguishes Johnston’s film from Hickham’s memoir is its depiction of unionism. The film makes its first explicit reference to the local union when Roy Lee’s drunken stepfather, Vernon (Mark Jeffrey Miller), beats him. After John intervenes, Vernon threatens to report him to the union—to which John responds, “Screw you and your damn union.” The scene is unambiguous. On the one hand, it aligns the union with the ersatz father whose abuse and alcoholism pose a threat to Roy Lee’s future. On the other hand, it establishes John as a kind of imago of individualism, anticipating the rapprochement between Homer and him.[36] Later, when the local union finally does go on strike, the film underscores this sympathetic image of John. A brief episode depicts an anonymous union organizer standing on a pulpit from which he demagogically addresses a mass of coalminers. A high-angle shot frames the one-sided interaction, imbuing it with an undemocratic energy. The union organizer’s suit stands in sharp contrast to the blue coveralls worn by the miners, suggesting that he is but an interloper who does not have the best interest of his constituents in mind. The film then cuts to the Hickham household, where John calls the striking coalminers “ungrateful sons of bitches.”[37] When John moves into the kitchen, a bullet comes whistling through the window, and the ensuing sequence reveals Vernon as the shooter. In moving from the public outrage of a mass of undifferentiated laborers to violence directed at John, the film forecloses audience sympathy for the strikers. To the extent that Vernon is viewed as a synecdoche for the union, October Sky figures the strike as a threat to the Hickhams’ wellbeing.

This morally Manichaean treatment of union activity does not reflect the time period in which the film is set so much as a distinctly neoliberal vision of entrepreneurial freedom. To be sure, lest I be accused of a nostalgic view of coalmining, my focus here is not on the film’s portrayal of the industry as dangerous and outmoded but on its portrayal of unionism as a symbol of ungratefulness and greed. Historically, Coalwood’s local union would have fallen under the administrative control of John L. Lewis’s United Mineworkers of America (UMWA), whose historical legacy is murky and complex. In An Injury to All, Kim Moody locates a decisive shift in twentieth-century capital-labour relations in the late 40s, a brief period that witnessed the end of World War Two; the commencement of the Cold War; and the ratification of the Taft-Hartley Act, a bill that imposes severe restrictions on union activity. Partly as a consequence of this bill and the fervent anticommunism spreading across the nation, many labor unions abandoned radical methods, choosing instead to adopt a bureaucratic model of business unionism whereby authority became increasingly centralized in the administrative division of the organizations. This development would ultimately favor capital. It deprived rank-and-file members of their political power and autonomy, limiting union activity to bargaining for better wages and benefits. That said, Lewis’s UMWA, structured no doubt according to this bureaucratic model, was the first national union to establish a health and pension plan for its members.[38] As Moody points out, despite its tenuous reliance on the postwar economic boom, “modern business unionism brought a significant improvement in living standards to millions of workers. [. . .] [M]ore workers participated in the era of affluence to a degree no working class had previously experienced.”[39] This ambivalent account of midcentury developments in capital-labor relations highlights that unionism, improvident strategies notwithstanding, still constituted an effective and legitimate collective expression against the violence of capitalist exploitation. Belonging to a union during this time meant more security, on the one hand, and an opportunity to participate in the good life of postwar prosperity, on the other.

In Rocket Boys, Hickham portrays the local union in a more sympathetic light than the film does. While pointing out that certain members were abusive alcoholics like Vernon, Hickham also underscores that union activity functioned as the only viable mode of responding to the mining company’s abuse of power and unilateral decision-making. The company owned all the local homes and most of the businesses, and Hickham figures the various company superintendents as interlopers in Coalwood. In the center of town, situated atop “an overlooking hill was the turreted mansion occupied by the company general superintendent, a man sent down by our owners in Ohio to keep an eye on their assets.”[40] His description of a particular superintendent, Mr. Fuller—“He talked like a machine gun and had about as much charm”—is unequivocal.[41] Here, rather than a suited union organizer, it is the company man who is perceived as a threatening personage. As Hickham subsequently explains, “Mr. Fuller ordered a big cutoff and many men were given their pink slips. Mr. Dubonnet [a coalminer and the head of the local union] called an emergency meeting at the union hall and invited the company to explain. Mr. Fuller didn’t show.”[42] For the people of Coalwood, this passage suggests, unionism translated collective fears and dismay into political action.

Johnston’s film, on the other hand, expresses communal solidarity through a historically inaccurate picture of Coalwood as an inclusive, de-segregated town. While Hickham makes clear that Coalwood was still segregated in the 50s, the film obscures this reality with the character Leon Bolden (Randy Stripling), a black welder who helps the boys build their rockets. Towards the end, when Homer’s materials are stolen from his display at the national science fair, Leon evinces a willingness to cross the union’s picket lines in order to weld him a new rocket. Although he performs a helpful service for the boys—and therefore arguably unsettles my reading of the film’s commitment to individualism—he does very little beyond that. He is a flat character whose presence indicates nothing about local race relations other than the fact that the town is not all white. His desire to help Homer at all costs, even if it means scabbing and putting himself in a precarious position vis-à-vis his colleagues, highlights more clearly the anti-union theme running through the narrative.[43] The point here is not to reproach the film for its depiction of peaceful race relations within Coalwood; however, this particular departure from Hickham’s memoir is a conspicuous example of the film’s Third Way bent. To put institutionalized racism under erasure while simultaneously making collective action a referent for greed and sloth is to undermine, at least symbolically, the very strategy of political mobilization that powered the Civil Rights Movement. In so doing, the film weds its celebration of entrepreneurship to a post-Civil Rights view of race relations, a combination redolent of Third Way politics.

Conclusion

Historical discourse, de Certeau contends, “places both absence and production in the same area.”[44] The social, economic, and political conditions of the present inflect the intelligibility of bygone eras. As I have shown, big-budget studio films about the past, be they ironic or sincere, tend to reveal more about the dominant ideology circulating during the time of production than the time period being aesthetically rendered. At first blush, Pleasantville makes this point for viewers: its late-90s characters infuse a late-50s sitcom world with contemporary social values. Yet a deeper investigation reveals conservative currents running through the film, ones that reflect the oblique way in which Clinton’s Third Way politics preserved white-male hegemony. On the other hand, October Sky seems to be invested in faithfully rendering onscreen Hickham’s Rocket Boys. Yet with its unambiguous celebration of individualist striving, Johnston’s film has captured the energy of its source material and swerved it towards an end more faithful to Third Way politics than midcentury America. Performing the cultural work of political hegemony, these films suggest how hypertrophic memory can foster the desire to grasp what is no longer available at the expense of critically examining the present with the past in mind. The consequences of this development cannot be overstated. When the past is fetishized to the point that it no longer serves a pedagogical function in the present, avenues to more democratic futures become increasingly difficult to envision.

Author Biography

Daniel Dufournaud is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at York University, Toronto. His dissertation looks at contemporary American literature that responds to the social and economic conditions of neoliberalism.

Notes

Michel de Certeau, The Writing of History, trans. Tom Conley (New York: Columbia UP, 1992).

Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2003), 29.

Marita Sturken, Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering (Berkeley: U of California P, 1997), 10.

Alan Nadel, Containment Culture (Durham: Duke UP, 1995), 91.

Donald Pease, The New American Exceptionalism (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2009), 130.

To be clear, while historical and nostalgic studio releases dominated box offices in the 90s—a non-exhaustive list would include Ron Howard’s Far and Away (1992) and Apollo 13 (1995); Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), Amistad (1997), and Saving Private Ryan (1998); Edward Zwick’s Legends of the Fall (1994); Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995); and James Cameron’s Titanic (1997)—Nadel makes clear that previous decades in American popular film witnessed commercially successful, and politically charged, films about the past. What distinguished the 90s, however, was the way technological innovations, rampant consumerism, partisan politics, and the imminent fin de siècle coalesced to heighten interest in the past. Accordingly, scholars have situated 90s American film within this context of “hypertrophic memory,” as cinema’s centennial inspired retrospectives, all-time-best lists, and appraisals of film’s historical trajectory: see, for instance, the introduction to 90s film in Linda Ruth Williams and Michael Hammond, ed. Contemporary American Cinema (New York: Open UP, 2006), 325-333.

De Certeau, The Writing of History, 29-30 (emphasis original).

All box-office information comes from Internet Movie Database, at “imdb.com.”

Jim Collins, “Genericity in the Nineties: Eclectic Irony and the New Sincerity,” in The Film Cultures Readers, ed. Graeme Turner (London: Routledge, 2002), 276.

Bill Clinton, “Address Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Democratic National Convention in New York,” Speech, Democratic National Convention, New York, New York, July 16, 1992, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=25958.

On a global level, the most detailed evidence of growing wealth inequality is to be found in Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2014). Examining the richest countries in the world, Piketty attributes this phenomenon in part to the gradual privatization of public assets. He also underscores that, since the 1970s, the central political administrations in these countries have favored the growth of private wealth.

David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005), 50.

Lisa Duggan, The Twilight of Equality?: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (Boston: Beacon, 2003), 15.

Cathy Schlund-Vials, War, Genocide, and Justice: Cambodian American Memory Work (Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2012), 77.

For a detailed study of how white Americans benefited from the dispossession of minority communities in the twentieth century, see George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics (Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1998). As Lipsitz shows, Clinton’s “New Covenant” could not have overturned the years of institutional inequality underwriting white hegemony. In his speech at the Democratic National Convention, Clinton declaimed that the “most important family policy, urban policy, labour policy, minority policy, and foreign policy American can have is an expanding entrepreneurial economy of high-wage, high-skilled jobs” (Clinton, “Address”). For Clinton, equalizing life chances required the expansion of the market.

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books, 1994), 112.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 1991), 279-296.

Paul Grainge, “Colouring the Past: Pleasantville and the Textuality of Media Memory,” in Memory and Popular Film, ed. Paul Grainge (Manchester: Manchester UP, 2003), 212. Grainge’s reading of Pleasantville as a film that disrupts neoconservative fantasies about the 50s is echoed in Laura Crossley, “The Capra Touch: Nostalgia Culture in American Film,” Film International 15, no. 1 (2017): 11-22.

Grace Elizabeth Hale makes this argument in her study of postwar radicalism, pointing out its shortcomings, oversights, and unintended conservative consequences. The romance of the outsider, she argues, drew white radicals to the margins, but this centrifugal movement pivoted largely on stereotyped fantasies about nonwhite people and did not translate into a demand for redistribution. Neoliberal policies, emphasizing entrepreneurial self-determination, subsequently catered to white middle-class disaffection without changing the material structures of inequality; see, in particular, Grace Elizabeth Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in love with Rebellion in Postwar America [Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011], 132-237.

Joseph Darda, “Military Whiteness,” Critical Inquiry 45 (Autumn 2018): 78-79. In this article, Darda attends to how the frequent deployment of the deracialized veteran American in both multiculturalist and neoconservative discourses under and since the Reagan administration has tacitly worked to establish “a new white racial politics”; this figure “emerged as a site of consensus in the culture wars by situating the white veteran as a deracinated universal and a minoritized outsider” (Joseph Darda, “Military Whiteness,” 79, 78).

Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 23.

Richard Armstrong reads the gender discourse of the film differently, suggesting that “it is the women of Pleasantville who trigger, and sustain, the revolution (Richard Armstrong, “‘Where am I going to see colours like that?’: Bliss, Desire and the Paintbox in Pleasantville,” Screen Education 52 [Summer 2008]: 155 [emphasis mine]). While Jennifer/Mary Sue certainly inaugurates the revolution in Pleasantville, this reading overlooks the latter half of the film in which Bill and David/Bud carry the revolutionary burden. The repeated association of women with the private sphere, moreover, is not revolutionary but indicative of conservatism.

The film’s focus on consumer choice as a sign of progress echoes the shift from Fordist to post-Fordist production processes that accompanied the ascension of neoliberal capitalism. While Fordism was associated with economies of scale, which paired large-batch production with little product diversity, the growing strength of transnational markets towards the end of the twentieth century made post-Fordist production methods more viable and lucrative. Post-Fordism is characterized by an economy of scope, which pairs small-batch production with greater product diversity. Thus, the film undoubtedly moves in lockstep with Jameson’s Marxian formulation of postmodernism, “coordinating new forms of practice and social and mental habits [. . .] with the new forms of economic production and organization” (Jameson, Postmodernism, xiv). However, new practices and habits do not amount to a revision of established social hierarchies. For an introduction to post-Fordism, see Ash Amin, ed. Post-Fordism: A Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994).

Sharon Willis, The Poitier Effect (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2015), 106.

Greg Dickinson, “The Pleasantville Effect: Nostalgia and the Visual Framing of (White) Suburbia,” Western Journal of Communication 70, no. 3 (2006): 223.

Willis, The Poitier Effect, 17. The whiteness of American suburbs, moreover, dates back to their inception, when racist lending policies mingled with government subsidies to create racially homogenous social spaces on the outskirts of urban areas (see Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, 24-46).

In this section, I use “Homer” to refer to the protagonist in Johnston’s film and “Hickham” to refer to the real-life memoirist.

Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997), 14.

Individualism qua entrepreneurship is a fundamental tenet of neoliberal discourse. For a detailed discussion of neoliberal theory, see Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics, Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Picador, 2008), 215-265.

For a fuller discussion of neoliberal policies’ atomization of the social body, see Michel Feher, “Self Appreciation; or, the Aspirations of Human Capital,” trans. Ivan Ascher, Public Culture 21, no. 1 (2009): 21-41. See also Maurizio Lazzarato, “Neoliberalism in Action: Inequality, Insecurity and the Reconstitution of the Social,” trans. Couze Venn, Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 6 (2009): 109-133.

Homer H. Hickham, Jr., Rocket Boys (New York: Delta, 1998), 355.

One could argue, in opposition, that Wernher von Braun, the (in)famous rocket engineer, serves as an idealized figure for Homer. However, the film downplays von Braun’s impact on Homer’s work ethic and subsequent triumph. When a crowd surrounds Homer after he wins the national science fair, an attendee detaches from it to tell Homer that the latter “just shook his [Wernher von Braun’s] hand.” The film lingers for a moment on Homer looking surprised but quickly cuts to his arrival back home, rushing ahead to the aforementioned juxtaposition that punctuates the narrative. Therefore, as a figure of individualism unhampered by collective goals, John carries decidedly more thematic weight in the film than von Braun.

Ironically, Chris Cooper, who plays John, stars in John Sayles’ Matewan (1987), in which he plays a union organizer who comes to a West Virginian mining town in 1920 to unite workers against their employer.

An anonymous reviewer informed me that October Sky partly inspired Jeff Bezos’s interest in space tourism; as I write, the founder and C.E.O. of Amazon is mobilizing the resources to turn this interest into reality. A detailed discussion of Bezos’s meteoric rise (no pun intended) is, of course, beyond the scope of this paper, but it is telling that Bezos, often lauded as the doyen of entrepreneurial success, has benefited a great deal from the neoliberal assault on collective living codified in the film’s themes. For more on the film’s influence on Bezos’s supra-planetary ambitions, see Steven Levy, “Jeff Bezos Wants Us All to Leave Earth—For Good,” Wired, October 15, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/jeff-bezos-blue-origin/. For fuller discussions of the policy work fueling Amazon’s spectacular growth, see Annie Lowrey, “Jeff Bezos’s $150 Billion Fortune Is a Policy Failure,” The Atlantic, August 1, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/08/the-problem-with-bezos-billions/566552/; and David Pegg, “From Seattle to Luxembourg: How Tax Schemes Shaped Amazon,” The Guardian, April 25, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/25/from-seattle-to-luxembourg-how-tax-schemes-shaped-amazon. For an inquiry into Amazon’s history of union busting, see Verne Kopytoff, “How Amazon Crushed the Union Movement,” Time, January 16, 2014, http://time.com/956/how-amazon-crushed-the-union-movement/.