Supergirl vs. Overgirl

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Superman (with a big S on his uniform –we should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.) needs an endless stream of ever new submen, criminals, and “foreign-looking” people to not only justify his existence but make it possible...either [readers] fantasy themselves as supermen, with the attending prejudices against submen, or it makes [readers] submissive and receptive to the blandishments of strong men who will solve all their social problems – by force.[1]

Fredric Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent (1954)

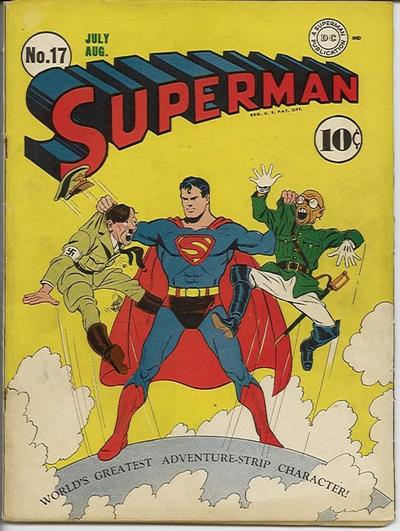

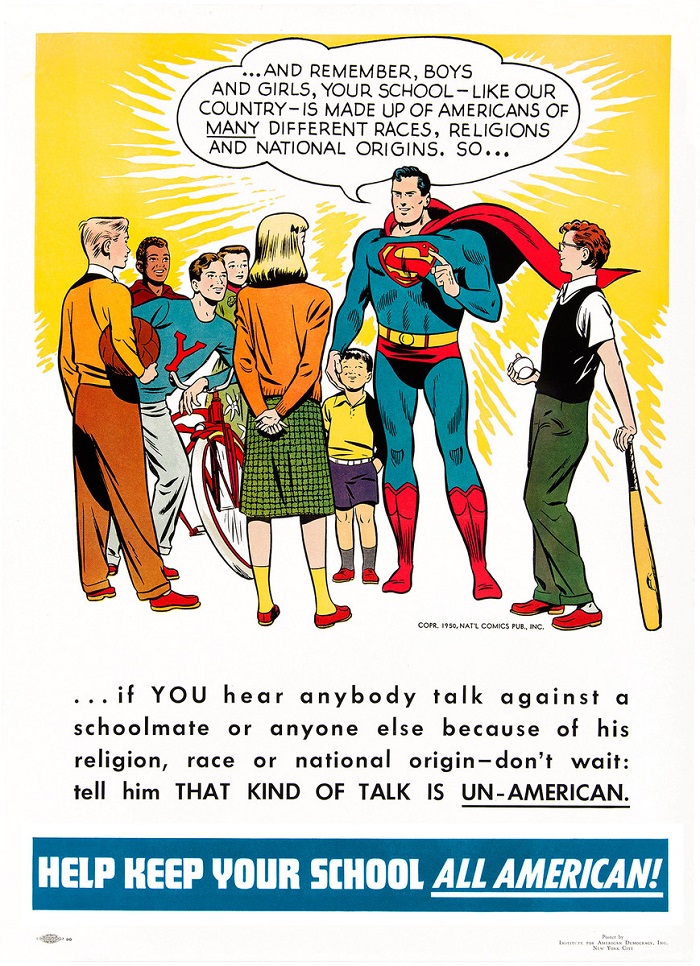

Like any comic book narrative, the critical discourse surrounding comics required a “super-villain.” Enter Dr. Fredric Wertham. In the post-World War II era, Wertham became the principal critic of the comic book industry as a leading contributor to juvenile delinquency and general corruptor of the moral fiber of American adolescents. To be sure, there is much to be critical of Seduction of the Innocent as far as its sloppy sociology, questionable rhetoric, and blatant homophobia. However, the thorny issue Wertham raised was not simply a social conservative attack on “indecency” in the comics but more productively a critique of the superhero as a figure somewhere between vigilante and avenging angel: an all-powerful arbitrator and image-ideal of justice. By extension, Wertham’s analysis posits a relationship between mass culture and an authoritarian world-view comparable to the sociologists of the Frankfurt School, especially Theodor W. Adorno.[2] In other words, by marginalizing Wertham as a right-wing crank, staunch comic book defenders ignore the extent Seduction of the Innocent functions as a radical critique of potential fascist elements of comic books. The CW television network’s “Arrowverse” shows are derived from DC Comics. In one arc, Crisis on Earth-X (originally aired on November 27-28, 2017), four one-hour episodes feature cross-over segments between Supergirl, Arrow, The Flash, and Legends of Tomorrow. The central conflict involved an invasion by Earth-X, a parallel world in which the Third Reich won World War II. The superheroes on Earth-X are devout Nazis; Supergirl’s political “other” is Overgirl. As Figure 1 shows, Overgirl is a white blonde super-being inscribed with the colors of Nazi Germany (black, red, and white) and the Waffen-SS logo on her torso. As one character put it in the first Crisis on Earth-X episode, Overgirl and her ilk are intent to “make America Aryan again,” an overt commentary on post-Trump America. In the second episode, Overgirl confronts Supergirl over the superiority of the Earth-X political order as a “meritocracy” based on domination and supremacy while assailing Supergirl: “You squandered the potential,... the most powerful being of the planet rendered weak by saccharine Americana.”Overgirl is presented as the antithesis of Supergirl. But she also points to the ongoing struggle for Supergirl since the show’s premiere in 2015 in addressing the “saccharine Americana” that has become part and parcel of the Superman franchise. They feature superhero personae who have been boringly reduced to “the big blue Boy Scout/Girl Scout” and “super-cop.” During World War Two, Superman was among the many superheroes mobilized into jingoistic propaganda.

By the 1950s, the comic book industry agreed to “voluntary” self-censorship through the Comic Code Authority (similar to the Hays Code that dominated the era of Classical Hollywood Cinema). Superheroes became banal crime-fighters and paternal authority figures dispensing unobjectionable civics lessons well within the constructs of affirmative ideology. Moreover, the iconic Superman slogan – “truth, justice, and the American Way” – was not from the comic-books but an invention of the Cold War-era TV series, The {?} Adventures of Superman (syndicated, 1952-1958).[3]

In this context, the superhero has a certain fixed role as a cultural text: he or she is a generic superhuman corrector of social crises. However, what a superhero stands for can be modified within a specific historical context to represent or re-represent a certain world-view. The fundamental problem is that the iconography of Superman is now an eminently idealized and nationalistic figure divorced from historical moorings. This situation couches affirmative ideology – “truth, justice, and the American Way” – as a kind of Kantian categorical imperative through a signifier that is precariously kitsch, a nostalgic curio where dominant ideology is expressed as a pop culture catchphrase. Conversely, Supergirl has reconfigured the title character into a superhero who is a generational signifier, a superhero born of the Obama-era in opposition to Trumpism.

“Truth, justice, and American way” represented on Supergirl is feminist, inclusive, Millennial, multicultural, and progressive. Supergirl is an “alien” (i.e. immigrant), a refuge from the planet Krypton who concealed her superpowers well into her mid-twenties; she now works for the Department of Extra-Normal Operations (DEO), a government agency as concerned with protecting the civil rights of assimilated aliens as much as defending Earth from hostile extraterrestrial forces. Supergirl’s adopted sister is an openly gay DEO agent. The DEO supervisor is J’onn J’onzz (aka “the Martian Manhunter”), an alien shapeshifter with an alter ego of Hank Hershaw, a black man. A story arc in the second season of Supergirl concerning a wave of anti-alien sentiment in the USA was a non-too-thinly disguised allegory for the Trump Administration’s Draconian anti-immigration policies. In the episode “Exodus” (2017), a rogue {rouge would also be funny given the gender stuff!} government operation kidnaps scores of extraterrestrials living on earth, loads them on a spaceship, and attempts to deport them across the Universe to their likely demise. Supergirl rescues them and safely returns the illegally detained aliens to Earth. Indeed, the allusion is not made to Trump’s immigration policies but the Holocaust. During the 2017 Women’s March, Melissa Benoist made her “personal politics” perfectly clear with a very pointed message to Donald Trump that directly referenced her TV “alter-ego” of Supergirl:

It is not enough to observe in Crisis of Earth-X that Supergirl’s brand of “truth, justice, and the American way” is parodied by Overgirl into “truth, justice, and the Aryan way.” Supergirl represents the vanguard of progressive liberal democracy and Overgirl the harbinger of fascism on collision course. Intentionally or not, the larger critique that Crisis on Earth-X provokes is revealing as much as concealing the superhero’s latent authoritarianism. This is not dissimilar to the concerns raised by Fredric Wertham, his status as pariah in comic book critical discourse notwithstanding. The nagging question is that Supergirl, the progressive superhero and Overgirl, the fascist super-villain are identical: they are both super-beings whose only differentiation is the trappings of ideology. It is simply which costume they wear that defines their nobility or perfidy as they dispense omnipotent (albeit ideologically divergent) versions and visions of justice and social control. The same could be said for Batman, Captain America, Deadpool, the Guardians of the Galaxy, the Punisher, Suicide Squad, Thor, Wonder Woman, and the X-Men. As Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno noted, “The physical brutality of the physical superman is always trustworthy.”[4]

Endnotes

Fredric Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent (New York: Main Road Books, 2004 [1954]), 34. See also in Terrence R. Wandtke, The Meaning of Superhero Comic Books (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 109.

A recommended study is Bart Beaty, Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005).

To be sure, numerous attempts have been made to rebrand and “update” the Superman franchise over recent decades in film and TV, including the attendant Superboy and Supergirl characters. To fully assess these myriad efforts adequately is far beyond the scope of this specific essay. Rather, I would invite readers to pursue these issues in terms of what is briefly being proposed in this discussion of Crisis on Earth-X.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum, 1998), 66.