Where to, Berlinale? The 68th Berlin Film Festival

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The 2018 Berlin Film Festival was the penultimate under the direction of Dieter Kosslick. During the run-up, discussions about his successor somewhat eclipsed news about the program. In November, a group of 79 German filmmakers had published a five-sentence statement in Spiegel Online, asking for a complete overhaul of the festival. They recommended forming an international, gender-balanced selection committee charged with finding “an extraordinary curator who can put the festival on eye-level with Cannes and Venice. We’re expecting a transparent process and a new start.” Criticism of the Berlinale is not new. There have been complaints about a lackluster competition and a bloated line-up that squeezes its program into seemingly random sub-sections. Time and again, major directors have seen their films rejected or pushed into sidebars. What must have been particularly irksome to Kosslick was the fact that Maren Ade, Sebastian Schipper, Christian Petzold and Fatih Akin, four recent winners of a Bear, added their signature. Conspicuously absent was the one from Tom Tykwer, most recently celebrated for his Netflix-produced series Babylon Berlin, who headed up the international jury this year.

Yet as one Berliner mordantly quipped, “the Berlinale after Kosslick will look better than the Christian Democrats after Merkel.” And indeed, for all the justified misgivings, there’s a lot the organizers have been doing right, and the 2018 installment was further proof of that. The festival got off to an upbeat start with Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, an animated feature about a 12-year-old boy, Atari, and five abandoned dogs who gang up to help him find his lost pet Spot. In a futuristic Japan plagued by snout fever, the dog-hating mayor of Megasaki condemns all dogs to be deported to Trash Island, a gigantic garbage dump filled with toxic waste and foul water. The film is a stunning dystopian view of how a society, led by a tyrannical leader, discards its loyal servants, but it is also a tale about courage and friendship, which ultimately—no spoiler alert here—win the day. With voices by Bill Murray, Tilda Swinton and Greta Gerwig, Isle of Dogs is both an unmistakable Wes Anderson picture as well as a crowd pleaser, full of lush and quirky details that make you want to watch it again right away. And it is an extended homage to Japanese culture, with nods to the samurai tales of Akira Kurosawa (there’s even a decaying statue of Toshiro Mifune on Trash Island) and to Yasujiro Ozu’s portraits of troubled family relations. This is Anderson’s second foray into stop motion animation, after The Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), and equally as successful as his first. Here, as in many of his earlier films, the carefully elaborated sets resemble dioramas in which characters enter and exit along central perspectives well known from graphic novels; his flat space camera moves as if reading one panel after another, left to right, top to bottom. One could easily imagine Moonrise Kingdom or The Life Aquatic as an animated film or a graphic novel. And the mildly pessimistic world view of the Tenenbaum clan or Rushmore’s Max Fischer (Jason Schwarzman, who co-wrote the script for Isle) recalls that of Charlie Brown.

Having Isle of Dogs open the festival was a gamble that paid off for the organizers—an animated feature was a choice many considered not serious enough, and in a field of 19 contenders, spread out over nine days, the opening act easily gets forgotten. Yet the jury stayed alert and awarded Anderson the Silver Bear for best director. Acclaimed Korean auteur Hong Sangsoo was less lucky. His latest feature, Grass, screened in the Forum sidebar, presumably because the 66-minute black-and-white vignette about men and women chatting in a café was considered too light-weight for a Competition slot. Nevertheless, it’s vintage Hong, set almost entirely in the small confines of an alleyway coffeehouse where conversations revolve around dreams, love, or recovery from disappointment. The camera glides from table to table, and sometimes beyond, listening in on people who, even though they have apparently known each other for a long time, still talk like strangers. Exchanges begin over coffee and tea but frequently end up soaked in soju. Grass relies mostly on simple profile two-shots, with some startling zooms, while classical music (Offenbach, Wagner and Schubert), interspersed at unexpected moments, heightens the emotional impact. Among an ensemble of many Hong regulars, the character played by his muse, Kim Minhee (a 2017 Silver Bear winner for her role in On the Beach at Night Alone), stands out as a solo figure, quietly eavesdropping as she hides behind her laptop. Is she the author of it all? Bittersweet Grass marked Hong Sangsoo’s fourth festival premiere during the last twelve months, a director so prolific critics greeted the film as “his first feature this year.” Yet despite this work rate, he makes his craft seem effortless, which is the hardest trick of all.

It’s doubtful whether Grass would have had a real shot at a Bear, as the jury bestowed top honors to a film that divided critics and audiences, but somehow managed to rise to the top. Touch Me Not, the debut by Romanian Adila Pintilie, is an intentionally uncomfortable close-up of the human body and the boundaries of intimacy; its explicit sex scenes had journalists leave the press screening in droves. Also overlooked were critical favorites Ang Panahon ng Hallmaw/Season of the Devil by Lav Diaz, and Christian Petzold’s Transit, the strongest of four German Competition entries. Transit is loosely based on Anna Seghers’ 1944 novel of the same name, set in the early forties among German refugees hoping to escape France before the Nazis take over. In the film, Berlinale shooting star Franz Rogowski, who also starred as reclusive forklift operator in the endearing Competition entry In den Gängen/In the Aisles (Thomas Stuber), plays Georg, a German Jew on the run who assumes the identity of a certain Wedel, a writer who has committed suicide, so as to use his exit visa to Mexico (the country to which Seghers fled). In Marseille, a tenuous love affair develops between Georg and Marie (Paula Beer), Wedel’s wife, who remains unaware of her husband’s death. With his taciturn demeanor, strong physicality and slight lisp, Rogowski’s break-out performance recalls the charisma of a young Joaquin Phoenix, while the highly talented Beer, who here replaces Petzold’s long-time muse Nina Hoss and who was radiant in François Ozon’s Frantz (2016), seems a bit underused.

Transit is dedicated to Harun Farocki, Petzold’s long-time collaborator and mentor, who shared his passion for Seghers’ novel and who passed away in 2014. With its ghostly existences, its cases of mistaken identity and impersonation, and the theme of non-belonging, this is familiar Petzold territory, but it is also a significant step forward for the German auteur. For unlike the period dramas Barbara or Phoenix, Transit (dis-)places its protagonists into present-day Marseille, making their old-fashioned wardrobe, shabby leather suitcases, and letters written with fountain pens stand in stark contrast to modern police forces and contemporary gadgets. As a fearful European running for his life, Georg recognizes himself in today’s African immigrants in a subplot set in Marseille’s Maghreb ghetto, and repeated talk of fascism and cleansings (Säuberungen) establish visceral parallels between Nazi domination and the return of nationalism and xenophobia in the face of today’s refugee crisis. It is in exploring this jarring contrast to the fullest that Transit finds its own. When the credits roll over the Talking Heads’ thundering “Road to Nowhere,” we have reached a most startling finale to a daring exploration of the uncanny synergies between past and present.

In an interview with the Berlin daily Der Tagesspiegel, Petzold commented that the film was also a reaction to the complete invisibility of the many thousands of refugees who since 2015 have found a temporary home in Berlin: “Once or twice a week I play badminton at a gym across from Tempelhof airport, where for two years nearly 3,000 refugees lived. We don’t know their stories, we don’t even see them.” Karim Aïnouz’ intriguing documentary Zentralflughafen THF/Central Airport THF may well be a response to Petzold’s comment. It’s an attempt to give one of them, 18-year-old Syrian refugee Ibrahim, a face and a voice. For twelve months the film tracks him, and his friend Qutaiba, an aspiring doctor from Iraq who can only work as a translator, as they learn German and patiently wait to be granted political asylum. Central Airport THF is devoid of dramatic turning points or a larger contextualization of Europe’s political stance on the refugees; instead the camera observes their daily routine and their interactions with the many German volunteers who help them.

Yet as the title indicates, the real protagonist of Central Airport THF is not a single person but the building the refugees inhabit, supposedly temporarily. They are not housed in the spacious welcoming area where travellers used to arrive or disembark, still in mint condition, but in the enormous hangars for the maintenance of the planes. In this makeshift transit space, privacy hardly exists, as paper-thin walls allow for little intimacy, even though Aïnouz keeps a respectful distance. The film opens with a neatly embedded history lesson, as the camera follows a tour guide who explains the complex history of the airport, very much a reflection of Germany’s own. Constructed in 1927, the National Socialists greatly expanded the facility for commercial and military purposes, making it the largest office building in the world until the U.S. Pentagon was built. During the 1948/49 Berlin airlift, Tempelhof became West Berlin’s lifeline. When it was officially closed in 2008, the airfield was turned into a gigantic public park for biking, picnics and gardening, treasured by Berliners. Through their windows, the refugees can see this oasis of peace and leisure, silently hoping that at some point it’ll be their paradise as well.

Neatly divided into twelve chapters, Central Airport THF is the portrait of a building and the chronicle of its dwellers over the course of a year. Sergei Loznitsa’s Den’ Pobedy/Victory Day is a far more condensed record of a location, the Soviet War Memorial in Berlin’s Treptower Park, built in 1949 to commemorate 7,000 soldiers who fell in the battle for Berlin. Each year on May 9, the memorial becomes the setting for a vast gathering celebrating the victory of the Red Army over Nazi Germany. It’s a festive affair, with people dressed in their Sunday’s best, or in uniform, coming to stroll, picnic and sing, while others hold forth about the meaning of history. Loznista is well-positioned to look at German-Russian relations. Born in 1964 in Belarus, then a part of the Soviet Union, he grew up in Kiev, studied film in Moscow and has been living in Berlin for a number of years now. As in Austerlitz (2016), which followed tourists visiting a German memorial site on the former territory of a Nazi concentration camp, Victory Day is a strictly observational documentary and confined, from dawn to dusk, to one place; everything is implied, nothing explained—a concentrated exploration of a public space that forces viewers to come to their own conclusions. Is tolerating a victory parade of a former enemy an example of the Germans’ successful coming to terms with their past? Are those Germans or Russians belting out Soviet folk songs? And to what extent is this celebration a tacit endorsement of current Russian politics, such as the annexation of the Crimea or the war in Eastern Ukraine? We catch snippets of conversations and watch people endlessly posing for photos and selfies, but what does it all add up to?

As has become customary for the Berlinale, there was a strong line-up of films from Latin America, with both Competition entries winning awards. Las herederas/The Heiresses, the debut of Marcelo Martinessi, is a finely observed character study of Chela (Ana Brun) and her long-time partner Chiquita (Margarita Irún), members of the upper middle-class who have fallen on hard times and make ends meet by discretely selling off Chela’s possessions. When Chiquita is sent to prison for alleged bank fraud, the passive and quiet Chela has to take matters into her own hands and begins chauffeuring wealthy neighbors around. A regained financial independence brings with it a reawakening of sexual desire and unexpected insights into the lingering class hierarchy of post-dictatorship Paraguay. The film opens with Chela spying from behind a curtain as her bourgeois heirlooms are scrutinized by potential buyers. In the course of the film she will slowly move beyond complacency and embarrassment. For her subtle acting style, which conveys emotions mostly through her eyes and eyebrows, Brun won the award for best actress.

In contrast to Martinessi’s furtive observations Alonso Ruizpalacios’ Museo/Museum, winner for best screenplay, uses the star power of Gael García Bernal to full effect for its genre-bending, style-shifting heist thriller cum road movie cum buddy flick. Loosely inspired by the theft of some 140 Mayan and Mesoamerican objects from Mexico’s Museum of Anthropology on Christmas Eve 1985, Museum is a wildly entertaining romp that begins with the highly improbable, giddy heist, pulled off by Juan (Bernal) and his best friend Wilson (Leonardo Ortizgris, who also starred in Ruizpalacios’ Güeros). It soon leads into territory never before visited by this genre, as the two thieves quickly realize that they have been turned into public enemies loathed by the entire country. Smart insights into the compromised nature of museum collections and the very nature of archeology, which raise fundamental questions about personal and cultural identity, are paired with a sympathetic portrayal of Museum’s greatly flawed protagonists. The opening caption of the film boldly tells viewers “This story is a replica of the original,” but luckily it is so much more.

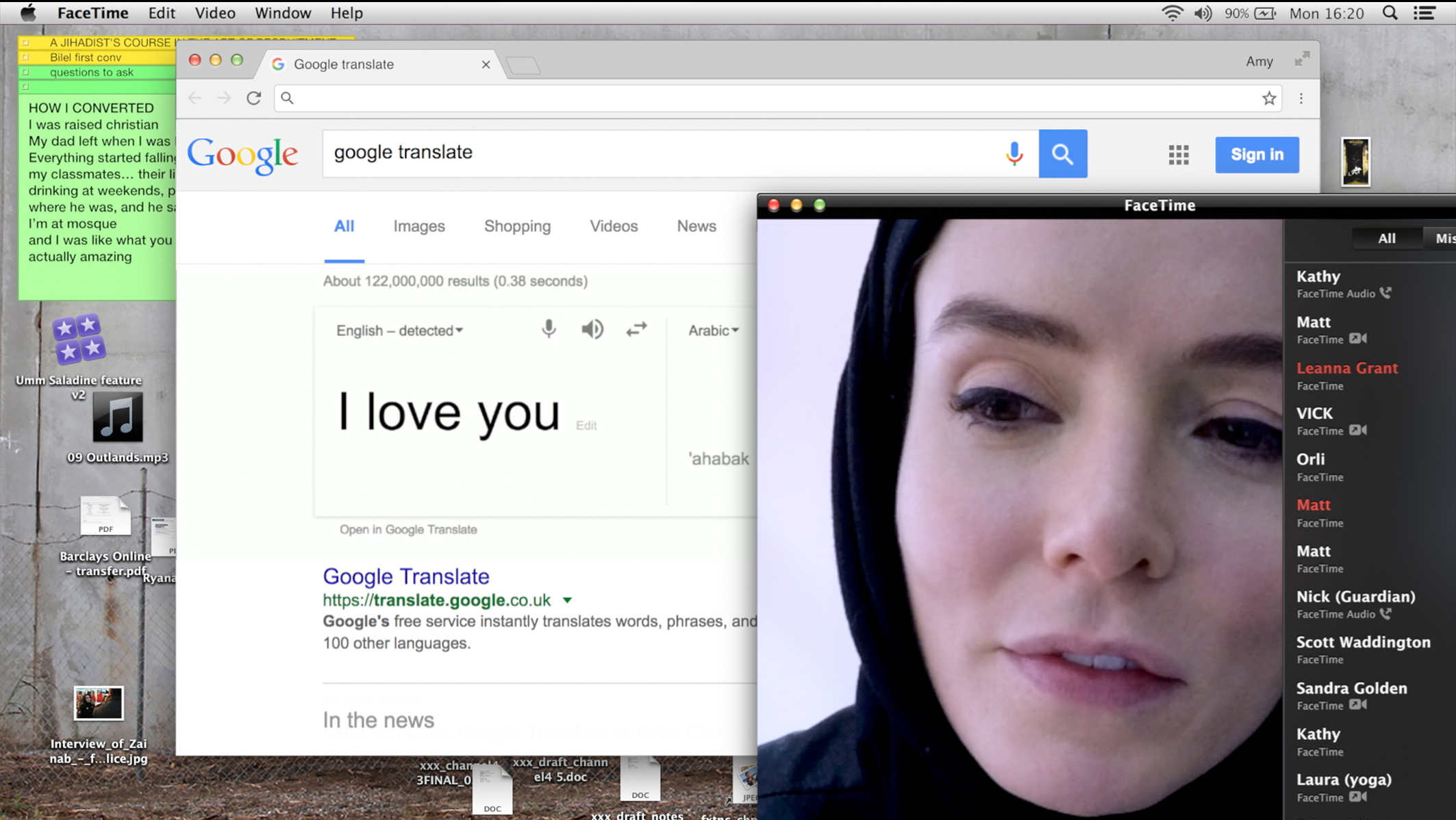

A personal favorite of mine, and the winner of the Panorama audience award, was Profile by Russian-Kazakh director Timur Bekmambetov (Wanted, 2008), a feature about London journalist Amy Whitaker (Valene Kane) who creates a fake Facebook profile to make contact with ISIS recruiters. Based on the book Undercover Jihadi Bride by a French investigative journalist writing under a pseudonym, the film is a tense political thriller that for a 105 breath-taking minutes shows nothing but Amy’s computer screen as she approvingly reposts footage of ISIS beheadings and quickly befriends a charismatic recruiter, all the while multi-tasking between requests from her editor, reminders of her overdue rent, and the complex demands of private life and romance. The desktop is a messy affair full of LOLs, GIFs, email notifications, and Google searches—a sensual overload that brings Amy more than once close to the brink, as the ever-increasing speed of social media makes her lose the ground under her feet. The repeated clips of European female ISIS converts stoned to death for trying to escape Syria firmly keep viewers alert about the high stakes of posing as live bait.

At a book launch held during the festival, former Berlinale director Moritz de Hadeln presented his biography, Mr. Filmfestival. Written by Swiss journalist Christian Jungen, the book is largely a celebration of de Hadeln’s fascinating career, but it also conveys some of the controversies surrounding his leadership. When he took over the festival in 1980, de Hadeln did so through a rather radical overhaul, leading to recurrent outspoken attacks and character defamation, in comparison to which personal criticism of Kosslick pales. During the discussion between the former and the current director, Kosslick confided that he has also been working on a memoir, clearly indicating that for him his tenure at the Berlinale is a soon to be closed chapter. Whoever will be writing the next one should be announced later this year.