“Too Marvelous for Words”: Bogart and Bacall’s Dark Passage Through Myth to the Enlightenment of Modernized Melodrama

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This essay explores Bogart and Bacall’s dark passage through words, written and spoken (myth), to performed roles accompanied by music too marvelous for words, to the enlightenment of director Delmer Daves’ modernized melodrama, which is premised in a synthesis with a version of Bazinian reborn realism, and which functions to demythologize the stars, to reveal the truth of their experience as married artists working on location. Or so the myth would suggest.

How does one make sense of the nonsense that is Dark Passage (Delmer Daves, Warner Bros., 1947), the least well received of the four films starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall? The celebrity couple’s onscreen chemistry is famously privileged over the logic of the plot in their first two films, To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946), both directed by Howard Hawks at Warner Bros., but with Dark Passage, their third film, one has to ask: what were the stars and director Delmer Daves thinking?[1] The problem with the film, some variation of which is repeated in almost every review, is the “highly implausible story” that “doesn’t withstand scrutiny.”[2] And yet, it is precisely the critical act of scrutinizing the story (or rather the plot) that allows us to make sense of the nonsense.

French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss proposes that a highly implausible plot is often indicative of myth. He defines myth by its form rather than content; myth is language structured in a particular way, spatially, on two levels, with surface and depth, wherein its “slated” structure “seeps to the surface via a repetition process.”[3] Myth often seems highly implausible if we attend only to the surface of a text, where the plot unfolds in time, whereas the story starts to make sense if we also take the time to collect and bundle into binary oppositions the not-yet-meaningful fragments of potential meaning—“mythemes”—scattered at intervals in the spatialized depths of the text.[4] Given that we only know things relationally rather than in-themselves, gathering mythemes into bundled relations allows us to register their differences and contradictions, the basis upon which we are able to construct and attribute meanings to things. “Myth wants to send a message,” summarizes British anthropologist Edmund Leach, but because it does so across time and space, against a background of interference or noise, it relies on redundancy to communicate the message. The receiver “may very likely get the meaning of each of the individual messages slightly wrong, but when he puts them together, the redundancies and mutual consistencies and inconsistencies will make it quite clear what is ‘really’ being said.”[5] In short, it is precisely in scrutinizing the nonsensical plot of a myth that we are able to make sense of the story, to infer what is “really being said,” to construct the meaning and receive the message. An essential feature of myth is the meaning-making contributions of receivers.

Scrutinizing the words in the serial novel Dark Passage by David Goodis confirms the presence of myth. In keeping with the structure of myth described by Lévi-Strauss and Leach, there are redundancies in the plot designed to send a message, which involves Irene Janney’s irrational desire to rewrite the past in the present, to make the past “different from what it was,” mediating for readers in the immediate postwar era (in the present) the negative feelings associated with World War II (in the past).[6] In the past, Irene’s father Calvin Janney was accused of murdering his wife, Irene’s mother, and died in prison. In the present, Vincent Parry is accused of murdering his wife, escapes from prison, and is rescued by Irene. When Vincent proves reluctant to discuss his “life history” with Irene, she expresses disappointment with the circumstances in which she finds herself: “I thought it would be different from what it is. I did my little bit for you, and it hasn’t turned out the way I thought it would turn out.”[7] By taking the time to collect and bundle the mythemes, we are able to register their equivalences and differences and infer the story.

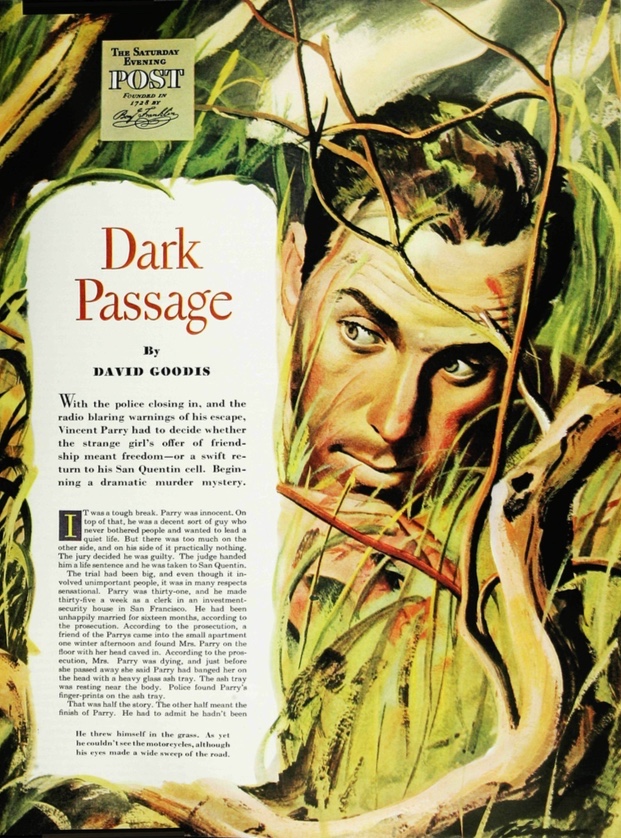

Figure 1. The novel Dark Passage by David Goodis was serialized in eight weekly installments in the Saturday Evening Post between July 20 and September 7, 1946.

Figure 1. The novel Dark Passage by David Goodis was serialized in eight weekly installments in the Saturday Evening Post between July 20 and September 7, 1946.The ninety-six minute film directed by Delmer Daves incorporates the plot of the Goodis serial novel but expands the myth to also send a message about the challenges confronting celebrities producing a film on location in and around San Francisco between late October 1946 and late January 1947.[8] Bogart and Bacall’s “life histories” were at the forefront of media attention preceding and during the production of the film. Everything they did was reported in print and on the radio.[9] Everywhere they went, reporters and fans crowded around them, pestering them with questions.[10] All these words, written and spoken, are not ultimately extra-textual; they are also part of the Dark Passage myth. Taking the time to collect and bundle the “life history” mythemes with those in the film allows us to construct and receive the message, thereby expanding the myth beyond the serial novel: Bogart and Bacall were annoyed by all the attention to their celebrity identities, as it hindered their work as artists striving to go beyond words on the page, to produce a visual and emotional architecture of faces “too marvelous for words” in accordance with the film’s theme song—in short, to produce a melodrama of performed roles accompanied by music.

Dark Passage figures not only the anxiety of celebrity actors who must translate words on the page (myth) into legible emotions on their faces “too marvelous for words” (melodrama) but also the anxiety of a Hollywood director striving to synthesize contradictory film styles (expressionism and realism) and camera perspectives (first and third person) in the service of making visible the artistic identities of his celebrity actors: to express how Bogart and Bacall know themselves and the world inwardly, as married working artists, and not simply how we and the studios see them outwardly, as celebrities defined by their “good faces” and “good clothes,” or by their performed roles as “tough guy” and “cool dame.”[11] Director Delmer Daves essentially seeks to demythologize his celebrity actors. Translated into cinematic terms, this involved countering how we see them in melodrama, in performed roles as expressed through classical Hollywood style, with how they know themselves and the world, as expressed through an expanded notion of realism premised in subjective camera technique and documentary style. In effect, Daves forges his own path toward the “reborn realism” of the 1940s described by French critic André Bazin, “giving back to the cinema a sense of the ambiguity of reality” by using subjective camera technique to depict the subjective verisimilitude of Bogart’s point of view as an illusion of continuous flow, temporally, and documentary style to depict the objective verisimilitude of Bogart and Bacall on location in San Francisco, spatially.[12]

This essay explores Bogart and Bacall’s dark passage through words, written and spoken (myth), to the melodrama of performed roles accompanied by music too marvelous for words, to the light at the end of the tunnel, the modernized melodrama of director Delmer Daves, which is premised in a synthesis with a version of Bazinian reborn realism, and which functions to demythologize Bogart and Bacall, to reveal the truth of how they know themselves inwardly, as working artists, and not just how we see them outwardly, as celebrities or performers of roles. Or so the myth would suggest. Although melodrama modernized by reborn realism purports to reveal the truth of Bogart and Bacall’s experience as working artists, it is still part of the same myth. Ultimately there is no escaping myth; there are only additions of new mythemes to the myth, including those that purport to demythologize the myth.

Dark Passage Through Myth

The film Dark Passage opens conventionally, if inauspiciously, with establishing shots of San Quentin State Prison, location footage recycled from a previous Warner Bros. film, San Quentin (Lloyd Bacon, 1937), also shot by Dark Passage cinematographer Sid Hickox and starring Bogart as a convicted felon.[13] “It would seem that mythological worlds have been built up only to be shattered again, and that new worlds were built from the fragments,” notes Lévi-Strauss notes, citing Franz Boas.[14] Whereas San Quentin portrays the experiences of Bogart’s character inside the prison, Dark Passage focuses on what happens to him on the outside, after he escapes from prison and fears being recognized by others. Stowing away in a barrel, Vincent Parry (Humphrey Bogart) tumbles off the back of a moving truck and lands in a wet ditch. Exiting the barrel, he peels off his shirt and hides in the bushes. Crawling along a fence line, he acknowledges the need to “start taking chances” if he is to avoid detection. He flags down a passer-by in a jalopy, Baker (Clifton Young), a small-time crook who considers himself big-time, who immediately asks too many questions: why Vincent’s feet are wet, where he’s going, why he’s wearing an undershirt, where he got his unusual pants, where he’s from. Fearing detection, attempting to divert attention away from himself, Vincent remarks on the “fancy seat covers” in Baker’s car. “That’s a piece of a carnival tent,” Baker replies, as he turns his attention back to Vincent and wonders aloud why Vincent isn’t more sunburned, given that he has apparently “lost his shirt.” Annoyed about having to “tell his life history,” Vincent demands that Baker stop the car and let him out. Just then, a bulletin is overheard on the car radio, confirming Vincent’s identity as an escaped convict. Taking full advantage of the first-person “camera-as-man” technique innovated by Daves (discussed below), Vincent socks Baker in the nose, knocking him out cold. Gathering the mythemes, we can immediately infer that Dark Passage is mediating its own production history, which involves celebrity filmmaker Bogart “escaping” the studio and going on location, “taking chances” as he tries to express himself artistically, while facing fears of “losing his shirt” financially and grappling with the distractions of unwanted media attention (radio) and “nosy,” annoying passers-by in fancy “carnival-tent” theater seats (moviegoers or fans) who interrogate him about his “life history.”

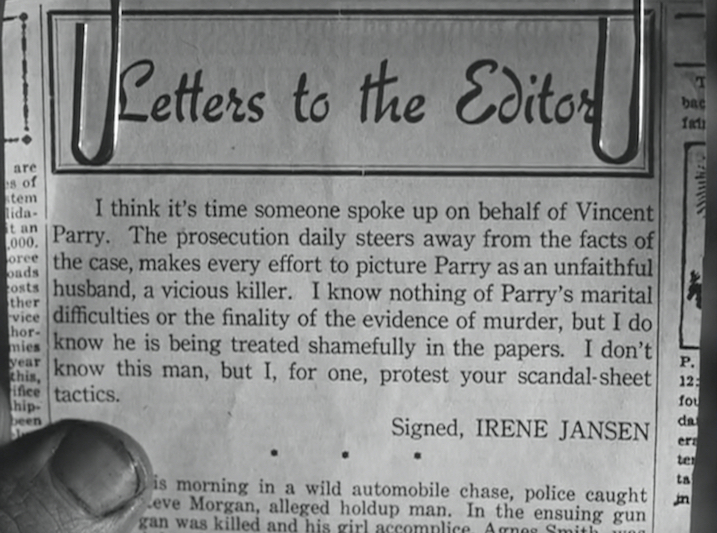

Words in a subsequent scene lend additional meaning to the film as an implicit mediation of the fears and anxieties of celebrity artists producing a film on location. At one point, Irene shows Vincent a newspaper clipping, a letter to the editor she wrote during his trial, lamenting his “shameful treatment in the papers” and their “scandal-sheet tactics” aimed at denouncing Vincent as an “unfaithful husband.” “I suspect you were getting a raw deal,” she explains.

Figure 5. Bogart and Bacall felt they got a raw deal, given the scandal-sheet tactics of the newspapers.

Figure 5. Bogart and Bacall felt they got a raw deal, given the scandal-sheet tactics of the newspapers.Bogart and Bacall had been married for a little over a year when they made Dark Passage, having weathered a storm of “shameful treatment” and “scandal-sheet tactics” in the papers regarding their possible affair and subsequent marriage, eleven days after Bogart divorced his third wife, actress Mayo Methot.[15] Apparently, Bogart and Bacall felt they got a “raw deal.” Or so the myth would suggest. The original problem, on both explicit and implicit levels of meaning, is conventional of melodrama, involving hesitation and uncertainty regarding the guilt versus innocence (villainy versus virtue) of the accused. Is Vincent guilty of killing his wife? Was Bogart guilty of an affair with Bacall while still married to Mayo Methot?

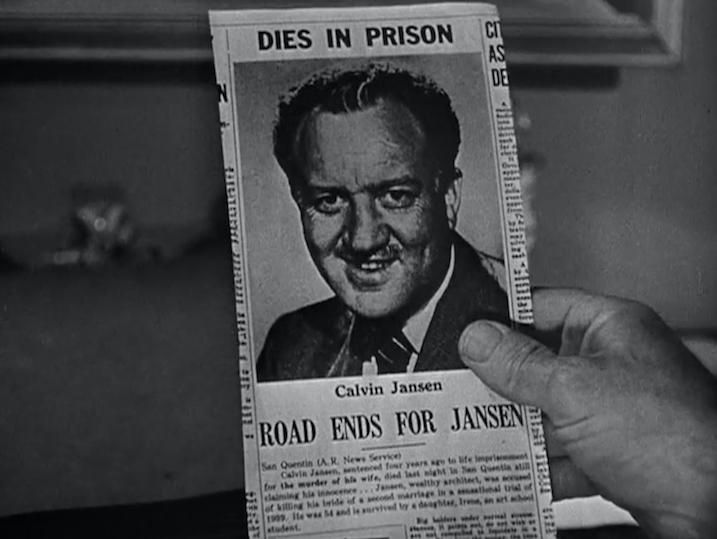

Upon escaping from prison (from the studio, from his first marriage), Vincent needs to “take a chance” (Bogart the artist) and Irene the landscape painter (Bacall the artist) “gives him a chance” by stowing him in the back seat of her car under some wet (unfinished) landscape (on location) paintings (the film). Bacall plays Eurydice to Bogart’s Orpheus, escorting him through and across, up and down, the landscapes of San Francisco, to her home, an uncanny space in a Streamline Moderne architecture, familiar yet unfamiliar, associated with “legitimate” swing music in the present, but also printed words in newspaper clippings which point to a scandal in the past, to the death of her architect father, pictured as the film’s “architect,” director Delmer Daves.

Figure 6. Director Delmer Daves, architect of the film, pictured in the newspaper as architect Calvin Jansen.

Figure 6. Director Delmer Daves, architect of the film, pictured in the newspaper as architect Calvin Jansen.Here, at home on location in San Francisco, the trauma of the past gives way to an ever-expanding myth, to Bogart and Bacall’s celebrity identities as a “legitimately” married couple, to the melodrama of their performed roles accompanied by music “too marvelous for words,” and to the truth of how they know themselves and the world as married working artists. Or so the myth would suggest.

A structural analysis of Dark Passage reveals that ultimately there is sense in the nonsense. The film coheres around the message of identity, of exterior (celebrity) versus interior (artist) self, as figured in Bogart’s protagonist Vincent Parry, who is anxious about his complicity with other characters (director and crew) in having perpetrated a “botched plastic job” on his own face (on celluloid) that has the potential (stylistically) to make him (the film) look like either a “monkey” (expressionism) or a “bulldog” (realism).[16] The verdict, post-surgery, is that Vincent’s new face (the film) offers a synthesis of contradictions (thematically and stylistically), presenting the “same eyes, same nose, and same hair” (of Bogart the celebrity, of classical Hollywood style) but with “everything else in a different place” (Bogart the working artist, reborn realism). “It oughta work,” Vincent remarks as he gazes into a mirror, taking stock of his new hybrid face (film), adding, “If it’s all right with me, it oughta be all right with you” (the viewer). Despite negative reviews, Dark Passage was all right with many viewers, ranking thirty-third among the seventy-five top grossing films in 1947, fueled by the tandem star power of Bogart and Bacall.[17]

Figure 7. Bogart’s new hybrid face revealed: “If it’s all right with me, it oughta be all right with you.”

Figure 7. Bogart’s new hybrid face revealed: “If it’s all right with me, it oughta be all right with you.”And yet, the film also sends a message acknowledging that its artistic experimentation, its storytelling and stylistic hybridity, may not appeal to everyone. When Vincent shows up for the plastic surgery operation with Dr. Coley (Houseley Stevenson), he is greeted by Sam (Tom D’Andrea), the friendly cab driver, a “funny” sort of friend (viewer or fan) who will not “take the hint” to leave Vincent (celebrity Bogart) alone, and who confesses to being lonely, despite “seeing people” (on screen), because “they don’t talk to me.” Sam attempts to be encouraging towards Vincent by acknowledging “how bad these things (films) can be,” having just last week picked up a “dame” (character) in his cab whose face had been “lifted by a quack” (film director). “She got caught in the rain and the whole thing dropped down to here,” Sam remarks, gesturing from his face (outer celebrity) to his heart (inner artist). “She should have left it unlifted,” he concludes, siding with viewers who prefer that Bogart and Bacall stick with their roles as celebrities (as in their first two films) rather than artists (as in this film), and that meaning and style in their films remain explicit and classical (unlifted) rather than implicit and modernist (artfully lifted by a quack director).[18]

Figure 8. Sam the cabbie, gesturing from face to heart, thinks a character he picked up in his cab should have left her face unlifted (and that the film remain classical rather than modernist).

Figure 8. Sam the cabbie, gesturing from face to heart, thinks a character he picked up in his cab should have left her face unlifted (and that the film remain classical rather than modernist).Dr. Coley kindly tells Sam (viewer) that he “won’t need you here” (in the filmmaking process) and instructs him to “go in the other room and read a (fan) magazine.” Coley then invites Vincent to “sit back in the chair,” informs him that the operation will take “ninety minutes, no more, no less” (the typical length of a three-act studio-era Hollywood feature film), that he perfected his own “special technique” (camera-as-man) before being “kicked out of the medical association” (studio and going on location) twelve years ago (recent past), that his “method is based partly on calling a spade a spade” (realism) and that he “does not monkey around” (expressionism).[19] “Ever see any botched plastic jobs?” Dr. Coley continues, doubling director Daves as he preps Vincent for the operation. “If a man like me (director) didn’t like a fellow like you (celebrity actor), he could surely fix him up for life. Make him look like a bulldog (realism), or a monkey (expressionism).” Dr. Coley then gives Vincent a “fine anesthetic used in the last war” to mask the pain—implicitly referring to the cultural function of cinema in mediating the fears and anxieties of popular audiences during the war years (in the past).

Vincent’s hallucination during the operation constitutes a mini-version of Dark Passage as an architecture of faces. Almost every character appears in close-up in the hallucinatory film-within-the-film, including “friends” who perceive Vincent as innocent, such as Irene (Bacall), Sam (viewer), and musician-artist George Fellsinger (Rory Mallinson), as well as “pests” who deem him guilty, including Baker the small-time crook who thinks of himself as big time (studio executive), and former girlfriend Madge Rapf (Agnes Moorehead), who keeps rapfing at the door (of consciousness) and insisting that Vincent (as an identity) is “nothing but an escaped convict” (celebrity on location) and that “nobody knows what [he] wrote down” (his version of the story as an artist).[20] Dr. Coley (director Daves) also appears in the highly expressionistic meta-film, repeatedly asking for money and laughing maniacally as he threatens to turn Vincent (celebrity Bogart) into a bulldog or a monkey.[21] When Vincent wakes up from the surgery, Bogart’s face is revealed for the first time through the camera’s third-person perspective, but is hidden behind mummy-like bandages restricting his ability to talk, figuring the muteness of melodrama and setting in motion the film’s goal of creating for viewers a visual and emotional experience “too marvelous for words.”

Figure 10. Madge Rapf, who keeps rapfing at the door of consciousness, insisting that Bogart is just a celebrity who escaped from the studio rather than an artist working on location.

Figure 10. Madge Rapf, who keeps rapfing at the door of consciousness, insisting that Bogart is just a celebrity who escaped from the studio rather than an artist working on location. Figure 11. Dr. Coley, doubling director Delmer Daves, threatens to turn Bogart into a monkey or a bulldog.

Figure 11. Dr. Coley, doubling director Delmer Daves, threatens to turn Bogart into a monkey or a bulldog. Figure 12. Bogart’s face is revealed for the first time through the camera’s third-person perspective, but remains hidden behind bandages that restrict his ability to talk.

Figure 12. Bogart’s face is revealed for the first time through the camera’s third-person perspective, but remains hidden behind bandages that restrict his ability to talk.Dark Passage into the Melodrama of Performed Roles

In contrast with myth, traditionally expressed orally, in words, melodrama is expressed in visuals and music. A more recent storytelling mode, migrating from Europe to America in the nineteenth century, melodrama essentially takes over from myth in the transition from ancient sacred to modern secular culture. Peter Brooks describes melodrama as a “text of muteness” in that it has something to say, it wants to send a message, but that something is repressed, buried in the “moral occult,” defined as a “repository of the fragmentary and desacralized remnants of sacred myth that bears comparison to the unconscious mind”—recalling Lévi-Strauss’s mythemes.[22] Inasmuch as melodrama is verbally repressed, it is highly expressive in other ways, in the visual elements of mise-en-scene accompanied by music. Linda Williams, following Brooks, argues that the function of melodrama is to orchestrate “moral legibility” for popular audiences. The virtue or villainy of character identities are made obvious, visible, in scenarios of pathos and action.[23]

On the explicit level of meaning, the melodrama of moral uncertainty in Dark Passage revolves around Vincent’s innocence (virtue) or guilt (villainy) in the death of his wife, while on the implicit level, uncertainty revolves around whether or not Bogart and Bacall are guilty of having an affair while Bogart was still married to his first wife, and producing a “botched plastic job” of a film. “Maybe you did it, maybe you didn’t,” Dr. Coley summarizes at the end of act two, leaving it to viewers to decide.

Conventional of melodrama, Vincent’s fears of detection as an escaped convict (villain, guilty) are expressed visually through camerawork, lighting, and costuming. For the first thirty-seven minutes of the film, his face is hidden off-screen behind a first-person camera. We have access to his voice-over narration, his words. After his plastic surgery operation, the camera switches to a more traditional third-person perspective, but his face remains shrouded in shadows or covered in bandages, and he cannot speak. One hour into the film, as the police search for Vincent intensifies, Irene removes Vincent’s bandages and reveals his new face, most of which is the “same” (celebrity) but some of which is “different” (artist). Dudley Andrew identifies this scene as the climax of the film, wherein “voice joins face to render a person in depth, a man with a past in other films and an off-camera life that is very public.”[24] Where there was once only Vincent, a performed role, there is now Vincent-Bogart, a performed role as well as a celebrity identity whose face and voice we recognize from previous films. Examining his new hybrid face in the mirror, Vincent-Bogart pronounces it “all right” (virtue). Seeking a “fresh impression,” Irene goes downstairs to await (with viewers) Vincent-Bogart’s entrance into the film in keeping with audience expectations of celebrity identity and performed roles, revealing his “good face,” wearing “good clothes,” accompanied by “legitimate” swing music. “It’s unbelievable,” Irene exclaims as Vincent-Bogart descends the staircase, “but it’s good” (virtue). The dark passage from myth (oral speech) to melodrama (visuals and music) is accomplished. Although the representation of Vincent-Bogart is a pleasing illusion, it has little to do with the authentic truth of Bogart’s identity as working artist. Or so the myth would suggest.

Bogart’s celebrity entrance, appearing as we know him from previous melodramas, exemplifies “predictive” acting as described by Murray Pomerance: “At stake is the identity of the star, not the characterization. Audiences pay for the pleasure of seeing star figures they know and value in advance. With predictive acting the viewer has a distinct sense of facing prior experience.”[25] Pomerance contrasts “predictive” with “transcendent” acting, which

stuns watchers by virtue of a seemingly sharp originality, a spontaneous burst of attitude and feeling that, springing out of—and away from—the narrative moment, brings a quality of intensity, novelty, and purity. [...] One has the sense of a gesture or action leaping away from the plot, perhaps making reference to film in general or the actor’s situation. [...] Suddenly and abruptly, the viewer can feel co-present with the character.[26]

In keeping with predicative performance for the moment, Vincent-Bogart insists that Irene-Bacall not change her face, as he likes it “just as it is,” underscoring his point by flipping the phonograph record over and playing “Too Marvelous for Words,” linking close-ups of Bacall’s face with music in the service of melodramatic expressiveness.[27] Continuing their mutually predictive performances, Bogart and Bacall kiss, renewing the pleasure we experienced watching similar scenes from their two previous films together.

Figure 15. Bogart and Bacall kiss, renewing the pleasure we experienced watching similar scenes from their first two films together.

Figure 15. Bogart and Bacall kiss, renewing the pleasure we experienced watching similar scenes from their first two films together.The romantic interlude is interrupted when Vincent-Bogart announces his determination to clear his name and prove who killed his wife, in keeping with the convention of nomination in melodrama, which is the dramatic moment when the “true” identity (and name) of a person is finally revealed and moral clarity is achieved.[28] Irene sends him out the door with a new hybrid name to go with his new face, Allan Linnell, a third term mediating the binary opposition of character role and celebrity actor, Vincent and Bogart. Removing the vowels in the name Allan Linnell reveals a palindrome of repeating letters, l-n-l-n-l, unveiling the binary difference at the foundation of symbolic language and human identity in culture, wherein to know something is to know what it is not. Identity is not intrinsic to things (the letter l, for example) or human beings (Vincent-Bogart), or for that matter, to cinema itself (ontology), but rather constituted in the play of difference with others—other things (the letter n), other human beings (Irene, viewers), other art forms (ontogeny) such as the serial novel from which the film is adapted. In short, remarks Dudley Andrew, paraphrasing an insight of structuralism, “Whatever ‘one is’ depends on the others one engages.”[29]

Hiding out in a hotel, where the manager notes his “unusual name,” Vincent-Bogart-Linnell is accosted by the annoying “pest” Baker (studio executive), who raps at the door and enters holding a gun, demanding money, and proposing to extort it from Irene-Bacall. As they get in Baker’s jalopy, the one with carnival tent seat covers (movie theater), and set out for Irene’s apartment, Baker chatters about his experiences in San Quentin (studio), where “they got some mighty smart guys,” a remark to which Bogart responds with a double-take, followed by a knowing look, letting the implicit meaning (critique) sink in.

Figures 16-17. Bogart’s double-take and knowing look in response to Baker’s remark regarding the “mighty smart guys” at San Quentin (at the Warner Bros. studio).

Driving the back roads, wending their way through actual locations as well as back projections in the studio, they end up under the Golden Gate Bridge—a spectacular architectural work and metaphor for the film itself, designed by the film’s “architect,” director Daves.

Figure 18. The Golden Gate Bridge, a spectacular architectural work and metaphor for the film itself.

Figure 18. The Golden Gate Bridge, a spectacular architectural work and metaphor for the film itself.Wrestling the gun out of Baker’s hand, Vincent-Bogart-Linnell questions Baker and confirms that Madge is the killer (villain) based on the evidence Baker provides. Just as Vincent-Bogart-Linnell is preparing to let Baker go, Baker lunges for the gun, they scuffle, and Baker accidently falls to his death.

The identity of the film as a visual architecture of faces is underscored when the architecture of the Golden Gate Bridge dissolves into a close-up of Madge peering through the architecture of a latticed porthole on her apartment door. Vincent-Bogart-Linnell peers back, Oedipus to her Sphinx. At first, Madge does not recognize him, given his hybrid face. “What is it, the suit? Or is it the face that doesn’t go with the eyes? It’s really me!” Vincent-Bogart-Linnell exclaims, in keeping with the convention of nomination.

Figure 19. Madge, peering through the architecture of a latticed porthole, does not recognize Vincent, given his hybrid face.

Figure 19. Madge, peering through the architecture of a latticed porthole, does not recognize Vincent, given his hybrid face.Having written down the evidence, his “truthful” version of events (as artist), he threatens to take it to the police, exposing Madge’s villainy. Madge, unperturbed, refuses to confirm his version of events, to “witness” his virtue (as artist). Without her, he has no proof of his innocence (his virtue as an artist). “You’re nothing but an escaped convict” (celebrity on location) she insists. “Nobody knows what you wrote down” (as artist).

Maneuvering with ambiguous motivations, Madge suddenly runs behind a curtain, crashes through the window (movie screen), and falls to her death. The “slaying” of the “monster” Madge (Sphinx) cues Bogart’s own curtain call, his transition from the space of performance, from the roles of Vincent Parry and Allan Linnell, into the “real world,” into the “truth” of his name and identity in culture, Humphrey Bogart the working artist.

Figures 22-23. Bogart’s curtain call.

Murray Pomerance discusses the theatrical curtain call and its cinematic analogies:

In the curtain call, the actor is given license to come away from character and suggest a hitherto hidden, or not yet full drawn presence. [...] We could say that characters and actors appear together and simultaneously, and that since the selfsame torso and appendages are being used at once by more than one being, a phantasmal quality attaches to the act of taking the bow or being seen in everyday life. The message addressed to the audience [...] implies not only a real world into which viewers can retire [...] but the real world out of which actors have emerged.[30]

Stunned by Madge’s strangely undermotivated actions (Sphinx), Bogart the working artist climbs up to the rooftop, down the fire escape, runs through and across the spatialized landscapes of San Francisco, and boards a streetcar. Cinematographer Sid Hickox takes full advantage of the location setting, presenting documentary proof of Bogart in San Francisco. It’s really him! Or so the myth would suggest. As evidenced by passersby and other annoying pests caught on camera, glancing and lingering as filming occurs on location at the corner of Powell and Market Streets, site of the famous streetcar turntable.

At the bus station, Bogart buys a (movie) ticket and the camera shifts attention to a woman with two children and a man (viewers) seated in a row, waiting for the bus (for the movie). A passenger off-screen asks whether buses “ever leave on time” and receives a flippant response from the ticket seller, prompting the seated woman to remark to the man, “A lot they care. They’re not worried about us.” “There was a time when folks used to give each other a helping hand,” the man replies, as Bogart eavesdrops, privileging hearing over seeing.

Figure 24. Bogart the artist eavesdrops on ordinary viewers, privileging hearing over seeing, music over the visual image.

Figure 24. Bogart the artist eavesdrops on ordinary viewers, privileging hearing over seeing, music over the visual image.“Sometimes I get sick and tired of everything. Nothing to look forward to at all,” the woman continues. “You’ve got these kids, that’s something. I got nothing,” the man replies, as it dawns on them that they have “something in common, being alone.” Bogart puts some coins in a jukebox to encourage the budding romance between the lonely hearts, once again privileging the soundtrack, and puts in a call to Bacall, filling her in on the details that will “be in the afternoon papers” (celebrity), but his version of events (artist), because he wants her to know “how it really was,” in keeping with the film’s quest for the truth of their identities, of their “life histories.” “I know how it was,” Bacall replies. She really does, having contributed to the production of the film. Overhearing the music on the jukebox, she asks if “there’s something else you want me to know,” as the music begins to supplant the need for words. He replies that he realizes “it’s better to have something to look forward to” and asks her to join him in South America when the coast is clear. “I won’t write,” he warns, freeing them once and for all from words. The film concludes with Bacall catching up with Bogart for a wordless romantic embrace in a seaside café in Peru (or San Francisco), accompanied by music—seemingly a predictive performance, in keeping with how we know them as celebrities and performers of conventionalized roles.[31] And yet, as they join the crowd of dancing couples, ordinary people, one has the sense of their actions transcending the plot, prompting the realization that we are co-present not just with the characters Vincent and Irene, not just with the tough guy and cool dame too marvelous for words, but with the married artists themselves. It’s really them!! Or so the myth would suggest.

Figure 25. Bogart and Bacall, married working artists, dancing on location among ordinary people. It’s really them!! Or so the myth would suggest.

Figure 25. Bogart and Bacall, married working artists, dancing on location among ordinary people. It’s really them!! Or so the myth would suggest.Passage out of Darkness: Reborn Realism

André Bazin famously valorized Hollywood directors Orson Welles and William Wyler and Italian directors Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio de Sica for their commitment to reality, for “giving back to the cinema a sense of the ambiguity of reality,”[32] each via distinctive paths, using different techniques, constituting the “reborn realism” of the 1940s—a stylistic trend that emerged in the silent era but receded in the 1930s as the conventions of the classical Hollywood and French sound cinemas were consolidated and stabilized. According to Bazin, the reborn realism of the 1940s “draws from [the silent era trend in realism] the secret of the regeneration of realism in storytelling and thus of becoming capable once more of bringing together real time, in which things exist, along with the duration of the action, for which classical editing had insidiously substituted mental and abstract time.”[33] In Dark Passage, Daves innovates his own version of Bazinian reborn realism by combining documentary style with subjective camera technique. Documentary style privileges the continuity of real-life locations, spatially, while the subjective camera technique produces an illusion of continuous flow, temporally.

Dark Passage is the first Hollywood feature shot with a small, portable Arriflex 35 camera originally designed for hand-held use on documentaries and newsreels.[34] The use of a hand-held camera facilitates the representation of objective verisimilitude in the startling scenes of Bogart running through the streets of San Francisco and jumping on a streetcar as the camera captures the double-takes of passersby. Shots of actual locations and ordinary people going about their daily business prompt us to suspend our disbelief in the illusion created by the film medium and accept what we see on screen as real. Yes, it’s really him. That’s Bogart! Or so the myth would suggest. His actions seem authentic rather than performed.

Figure 27. Bogart the celebrity artist on location in San Francisco, preparing to board a streetcar.

Figure 27. Bogart the celebrity artist on location in San Francisco, preparing to board a streetcar. Figure 28. Bogart the celebrity artist on location in San Francisco, attempting to avoid detection by onlookers.

Figure 28. Bogart the celebrity artist on location in San Francisco, attempting to avoid detection by onlookers.The hand-held camera also contributes to the subjective verisimilitude of the first thirty-seven minutes of the film in which Bogart’s face is hidden off-screen behind a first-person camera—an innovation director Daves dubbed the “camera-as-man” technique.[35] Through careful consideration and testing of lens choice and camera height, angle, and movement, Daves and cinematographer Sid Hickox sought to approximate as closely as possible how human beings actually see, through our own eyes, when we are walking, talking, lying down, or looking at our own hands and feet.

Figures 29-30. Approximating how human beings actually see, when we look at our hands and feet. The hands and feet likely do not belong to the same person.

Another level of subjective verisimilitude is also evident in Vincent’s hallucination during the plastic surgery operation. Here, the camera is aligned with Vincent’s mind’s eye rather than physical eye, representing realistically not what he sees but what he feels and imagines—a technique originating in German expressionism. Vincent’s hallucination is a verisimilar depiction of the subjective mindscape of a complex character as manifested through the film’s aesthetic of reborn realism. His hallucination has the continuous flow of an inner reality.

Figure 31. Vincent’s mind’s-eye hallucination, a verisimilar depiction of the subjective mindscape of a complex character.

Figure 31. Vincent’s mind’s-eye hallucination, a verisimilar depiction of the subjective mindscape of a complex character.In keeping with Bazin’s belief that “realism in art can only be achieved in one way—through artifice,” Daves’ remarks confirm that he used a great deal of artifice to achieve an appearance of versimilitude in Dark Passage.[36] Among the privileged techniques in Daves’ path to reborn realism is lens choice: “I will not use a dishonest lens. Many directors aren’t interested in lenses but a lens can make something dishonest very simply.”[37] Daves also describes the artifice he used to produce the subjective verisimilitude of Bogart’s point of view:

I had a shoulder holster, made to keep [the camera] at eye level, which was developed at Warner Bros. [...] and then the operating cameraman walked as [Bogart] walked. At first I thought how simple, just have the [camera operator] stand and do it all. [But] when I did my test it looked as if the shoulders were much too broad so I ended up [...] having two men being the two arms: one man was the right arm and one man was the left and they were right up next to the camera.[38]

In addition to this contrivance, evidenced in multiple shots of Bogart’s views of his hands and feet which are not his own, Daves sought to create the illusion of continuous flow in Bogart’s subjective point of view by using whip pans and disguised cuts—introducing into a postwar Hollywood melodrama the verisimilitude of temporal duration and spatial continuum of reality prized by Bazin. Daves explains: “I even had three operators on one shot to keep the flow of continuity because I discovered we don’t cut with our eyes as you cut in a normal film. Every shot was a problem, and instead of cutting I did whips. I whipped the camera, if we turn quickly, we whip, and I did the next shot to cut in on that whip.”[39] By way of achieving the objective verisimilitude associated with reborn realism’s documentary style, Daves insists that he “never subordinate[s] mere fact to dramatic use” and that he “does not like to arbitrarily work against a natural flow of action.” In filming Bogart, he “used the camera as realistically as I ever have and [...] didn’t use any make-up.” At the same time, Daves acknowledges the artifice of “super-imposing Bogart’s eyes and eyebrows [...] on the face of [the bandaged] double who did [Bogart’s] stunts.” Summing up his directorial approach, Daves states that he “much prefer[s] the audience not to know there’s a director,” validating David Bordwell’s point that “verisimilitude, objective or subjective, is inconsistent with an intrusive author.”[40]

Daves’s commitment to objective and subjective verisimilitude in Dark Passage anticipates a trend associated with the European art cinemas of the 1950s and 60s. According to Bordwell, the art cinema takes its cue from literary modernism in subscribing to an expanded notion of reality, encompassing the outer reality of the world as well as the inner reality of perception and the imagination, and strives to depict these realities as realistically as possible, by means of a correspondingly expanded notion of realism, encompassing both “documentary factuality” and “intense psychological subjectivity.”[41] Meanwhile, R. Barton Palmer identifies realism as a stage in the transformation of postwar Hollywood cinema, wherein “classical forms of filmmaking [...] made way, at least in part, for the modernist art cinema.”[42] James Naremore and András Bálint Kovács both position film noir as a transition step between the melodrama of the classical Hollywood cinema and the modernism of the art cinema.[43] Dark Passage, widely considered a film noir, brings specificity to these remarks as a case study, evidencing the transformation of the postwar classical Hollywood cinema as it makes way for the art cinema, decades before this influence is manifested in the New Hollywood films of the late 1960s and 70s. Ultimately Dark Passage fits the profile of 1940s cinema as the “first” New Hollywood described by Bordwell in his new book, in that the film “adheres to basic norms” of the classical Hollywood cinema while also “stretching the horizons” in the direction of the modernist art cinema to come[44]—by synthesizing melodrama with Bazinian reborn realism.

Enlightenment: The Modernized Melodrama of Delmer Daves

Overlooked in Bazin’s discussion of reborn realism and consigned by auteur critic Andrew Sarris to the category of the “lightly likeable” directors who are “talented, but uneven, with the saving grace of unpretentiousness,” director Delmer Daves seems a good candidate for critical rehabilitation based on the evidence of Dark Passage.[45] A recent volume of essays edited by Matthew Carter and Andrew Patrick Nelson focuses new attention on Daves. Carter and Nelson write:

As opposed to the “celebrity” status of a John Ford or a Howard Hawks, Daves is often regarded as an example of the self-effacing craftsmanship of classical and post-war Hollywood, a competent but conventional studio man who handled assignments professionally, but whose films lacked the kind of distinct perspectives and predilections detected by critics and scholars in the work of contemporaries like John Ford and Howard Hawks.[46]

Elsewhere in the same volume, Joseph Pomp writes that Daves was never canonized as an auteur because of his reliance on melodrama, “which was out of fashion amongst auteurists, who preferred the course masculinity of a John Ford or Raoul Walsh,” and that “aversion to melodramatic excess continues to be an impediment to Daves’ critical appreciation today.”[47] The latter point is confirmed in Jonathan Rosenbaum’s blog post in the wake of screening the Criterion Blu-Ray release of one of Daves’ westerns, Jubal (1956), that “once its excessive melodrama takes over, I found it close to unbearable.”[48] What Rosenbaum may find unbearable about Jubal is how this modernized melodrama functions to demythologize the western[49] —just as Dark Passage as a modernized melodrama functions to demythologize the noir posturing of the tough guy and cool dame in the service of revealing the truth of Bogart and Bacall as working artists. Or so the myth would suggest. I propose that Daves’ neglect as an auteur can be ironically attributed to the very techniques and strategies that define him as an auteur: he is a producer of modernized melodramas which function to demythologize traditional genres. The result: a “debunking of America’s cinematic frontier” in the case of the westerns, and a “diluted” film noir in the case of Dark Passage, favoring the tender interactions of married working artists over the performed roles of tough guy and cool dame.[50]

The storytelling and stylistic hybridity of melodrama in tension with Bazinian reborn realism is the “how” to the “what” of Daves’ authorship as a producer of modernized melodramas. Christine Gledhill observes that “realism’s relentless search for renewed truth and authentication pushes it towards stylistic innovation and the future,” while “melodrama’s search for something lost, inadmissible, repressed, ties it to an atavistic past.”[51] The atavistic past to which melodrama is tied is myth, as evidenced in my archeological excavation of mythemes buried in the Dark Passage myth. The textual stratigraphy of Dark Passage reveals a past of myth, rooted in a serial novel made up of words; a present layer of cinematic melodrama, as manifested in Bogart and Bacall’s predictive acting accompanied by music, which accords with classical Hollywood style; and an innovative future of reborn realism, which modernizes the melodrama by pushing it to express “truthful” reality, to introduce greater verisimilitude in the representation of reality—to replace “phony” or “fake” depictions of reality with “honest” ones, as Daves puts it.[52]

Ultimately Bogart and Bacall’s dark passage through the archaic past of myth to the present of cinematic melodrama which is modernized by the future of a reborn realism, aligns with Daves’ authorial concern with history as social progress and improvement, with dramatizing the passage from one social stage to another, from darkness to enlightenment, with each successive generation embracing the possibilities of a new era. According to Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns, “Daves was preoccupied with the transition taking place in America in the post-war years, and with the possibilities that this era would usher in a better world, one in which democracy, together with the economic growth and prosperity that follows it, would shine a light that would scare away the shadows of incivility.”[53] Carter and Nelson note along similar lines that Daves “repeatedly avowed the importance of cooperation and community for the advancement of society.”[54] Daves’ authorial investment in the values of civility, cooperation, and community runs counter to the values of individualism and competition privileged in the traditionally male-oriented “genres of order” identified by Thomas Schatz and preferred by early auteur critics, including westerns, gangster, and detective films.[55] Daves works in the “genres of order” identified by Schatz, but demythologizes these genres by introducing the values associated with the traditionally female-oriented “genres of integration” such as musicals, screwball comedies, and family melodramas, figuring those values through the storytelling mode of melodrama, which is modernized through film style, through a version of Bazinian reborn realism. Dana Polan is therefore mistaken in concluding that “Dark Passage gives us the negative existentialism of commitment to a nothingness, the instabilities of life and narrative falling prey to the inescapabilities of an historical absurd.”[56] Polan puts too much stock in the film as a noir without accounting for how the noir alienation—also central to J. P. Telotte’s argument about the film—is ultimately undermined by the more hopeful, optimistic values of modernized melodrama.[57]

Conclusion

Of the quartet of films starring celebrity couple Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, their third film, Dark Passage, was the least well received. The storytelling and stylistic hybridity of the film may prevent casual viewers from inferring a coherent story, from registering the sense in the nonsense. But it is precisely because of the film’s pronounced hybridity that it warrants our critical attention, exposing an archeology of storytelling and stylistic possibilities during a transformational period in postwar Hollywood. Excavating the film reveals that the ancient storytelling mode of myth, rooted in words, underlies the nineteenth-century storytelling mode of melodrama, which is figured in twentieth-century cinema via visuals and music—via Bogart and Bacall’s predictive acting style and music “too marvelous for words.” The melodrama, in turn, is modernized by a synthesis with Bazinian reborn realism, which strives to produce temporal duration and spatial continuity in the representation of reality, in this case through a combination of subjective camera technique and documentary style. Ultimately director Delmer Daves aims to demythologize Bogart and Bacall, to dilute the posturing associated with their celebrity identities and performed roles in favor of representing how they know themselves as married artists working on location. Despite the postwar taste for realism in film and the fascination with Bogart and Bacall as a real-life couple, reviewers and audiences preferred the melodrama of performed roles in To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946) over the reality of working artists in Dark Passage (1947). Auteur critics have likewise tended to favor genre mythologizers and celebrity directors such as John Ford and Howard Hawks over de-mythologizers and working artists such as Delmer Daves. Or so the myth would suggest.

Author Biography

Carol Donelan is Professor of Cinema and Media Studies at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. Her interests include melodrama and film noir as modes of visual storytelling and archival research on the history of moviegoing and film exhibition. Among her publications are essays in Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Film History: An International Journal and The Moving Image.

Notes

The fourth film Bogart and Bacall made together was Key Largo (John Huston, Warner Bros., 1948).

Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Structural Study of Myth” in The Journal of American Folklore 68.270 (1955), 229.

The word “mytheme” appears in the revised version of the “The Structural Study of Myth” included in Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1963), 211.

Edmund Leach, Claude Lévi-Strauss (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 63.

David Goodis, “Dark Passage,” The Saturday Evening Post (July 20, 1946), 44. Irene’s last name is changed from Janney to Jansen in the film version of Dark Passage.

The production dates for Dark Passage are listed in the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/Showcase.

For a discussion of how the star image is constructed not only in films but also in promotion, publicity, commentaries and criticism, see Richard Dyer, Stars (London: BFI Publishing, 1979), 68.

A. M. Sperber and Eric Lax, Bogart (New York: William Morrow, 1997), 333.

“Good faces” and “good clothes” are mythemes in Dark Passage, expressing how fans know celebrities. The references to “tough guy” and “cool dame” are from Rick Worland, “Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall: Tough Guy and Cool Dame” in Sean Griffin (ed), Movie Stars of the 1940s (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 70-95.

André Bazin, “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema” in Hugh Gray (ed), What is Cinema? Volume 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 23-40.

Warner Bros. recycled footage with abandon, as Eric Hoyt documents in Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 82.

The papers nicknamed Mayo Methot “Sluggy” due to her alcoholic combativeness. According to Rick Worland in "Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall: Tough Guy and Cool Dame," "Bogart and Mayo frequently engaged in physical as well as savagely emotional combat fueled by alcohol, jealousy, and rage, and often in public" (87). In Dark Passage, cab driver Sam interrogates Bogart about his life history. "What was she like?" Sam asks. "She was all right. She just hated my guts," replies Bogart.

We might just as readily classify monkey as realism and bulldog as expressionism. In keeping with structural analysis, what is significant is not the content of each term but rather the formal relation of the terms. The use of the terms monkey and bulldog are an example of totemism, wherein human beings use nature (especially animals) to think differences in culture. See Claude Lévi-Strauss, Totemism (London: Merlin Press, 1962), 89.

Despite being panned by critics and reviewers, Dark Passage earned a respectable 3 million, on par with To Have and Have Not (3.65 million) and The Big Sleep (3 million). “60 Top Grossers of 1947,” Variety (January 8, 1947), 8; “Top Grossers of 1947,” Variety (January 7, 1948), 63.

Conceiving of realism as a modernism rather than modernism as that which opposes and supersedes realism is explored by Colin MacCabe, “Bazin as Modernist,” in Dudley Andrew, with Herve Joubert-Laurencin (eds), Opening Bazin: Postwar Film Theory & Its Afterlife (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 66-76, and Dudley Andrew, What Cinema Is! (London: Wylie-Blackwell, 2010), 98-145.

Viewers today would be hard pressed not to register the unconscious racism in these remarks.

The one character who does not appear in Vincent’s hallucination is Bob (Bruce Bennett), who asserts that Vincent-Bogart is guilty not because he is a killer, but because he is “dumb, has no brains,” who “wouldn’t have come to Frisco in the first place (on location) if he (Bogart) had any brains.”

The shots of Dr. Coley laughing maniacally recall the shots of neighborhood women laughing maniacally in the doorman’s hallucination in The Last Laugh (F. W. Murnau, 1924), a classic German expressionist film.

Peter Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 5.

Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 30.

Dudley Andrew, “André Bazin: Dark Passage into the Mystery of Being” in Murray Pomerance and R. Barton Palmer (eds), Thinking in the Dark: Cinema, Theory, Practice (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 141.

Murray Pomerance, Moment of Action: Riddles of Cinematic Performance (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 21.

The tune “Too Marvelous for Words” was originally written for Ready, Willing and Able (Ray Enright, Warner Bros., 1937), starring Ruby Keeler. Johnny Mercer wrote the lyrics, Richard Whiting wrote the music, and Jo Stafford sang the tune, as noted in William Hare, Pulp Fiction to Film Noir: The Great Depression and the Development of a Genre (New York: McFarland, 2012), 124.

Brooks, The Melodramatic Imagination, 38; Williams, Playing the Race Card, 352.

Andrew, “André Bazin: Dark Passage into the Mystery of Being,” 112.

Pomerance, Moment of Action, 79. Richard Dyer also notes how stars “dramatize the problem of self and role.” Dyer, Stars, 181.

Daves’s version of reborn realism is largely achieved via on location shooting, but as he remarks, “that doesn’t necessarily mean the actual spot.” Christopher Wicking, “Interview with Delmer Daves,” Screen 10.4-5 (1969), 63.

Norris Pope, Chronicle of a Camera: The Arriflex 35 in North America, 1945-1972 (Jackson, University of Mississippi Press, 2013), 17.

David Bordwell, “Art Cinema as Mode of Film Practice” in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (eds), Film Theory & Criticism: Introductory Readings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 585.

R. Barton Palmer, Shot on Location: Postwar American Cinema and the Exploration of Real Place (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press), 106.

James Naremore, More Than Night: Film Noir and Its Contexts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 48; András Bálint Kovács, Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950-1980 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 246.

David Bordwell, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 478-479.

Andrew Sarris, American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1968), 171.

Matthew Carter and Andrew Patrick Nelson, “Introduction: No One Would Know It Was Mine: Delmer Daves, Modest Auteur” in Matthew Carter and Andrew Patrick Nelson (eds), ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 29.

Joseph Pomp, “Home and the Range: Spencer’s Mountain as Revisionist Family Melodrama” in Carter and Nelson (eds), ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves, 135.

Jonathan Rosenbaum. “The Delmer Daves Problem” (September 17, 2016), https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2018/01/the-delmer-daves-problem/

According to John White, the situation in Jubal involves the titular protagonist “learn[ing] that the strong, silent hero of the Western is a myth” and that “the individualistic ideology of the Western is insufficient for real human beings living in the real world.” John White, “Trying to Ameliorate the System from Within: Delmer Daves’ Westerns from the 1950s” in Carter and Nelson (eds), ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves, 70.

Sue Matheson, “Delmer Daves, Authenticity, and Auteur Elements: Celebrating the Ordinary in Cowboy” in Carter and Nelson (eds), ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves, 132. Bertrand Tavernier refers to Dark Passage as a “diluted” film noir in “The Ethical Romantic,” Film Comment (January-February 2003), 49.

Christine Gledhill, “The Melodramatic Field: An Investigation” in Christine Gledhill (ed), Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film (London: BFI, 1987), 31.

Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns, “Changing Societies: The Red House, The Hanging Tree, Spencer’s Mountain, and Post-War America” in Carter and Nelson (eds), Re-Focus: The Films of Delmer Daves, 180.

Carter and Nelson, “Introduction: No One Would Know It Was Mine” in Carter and Nelson (eds), ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves, 29.

Thomas Schatz, Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking, and the Studio System (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), 35.

Dana Polan, “Blind Insights and Dark Passages: The Problem of Placement in Forties Films,” Velvet Light Trap (Summer 1983), 33.

J. P. Telotte, Voice in the Dark: The Narrative Patterns of Film Noir (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989).