A Fallen Star Over Mulholland Drive: Representation of the Actress

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Looking at Naomi Watts’s dual role in Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001), this article argues that the film redefines the traditional Hollywood figure of the actress-character. Instead of reifying the authenticity of the diegetic actress, Mulholland Drive reveals the actress herself as a role to be performed.

In 2016, BBC Culture listed the 100 greatest films of the twenty-first century voted by critics from around the world. Ranked in first place was Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001).[1] Writer-director Lynch had just supervised a 4K restoration for the 2015 Blu-ray premiere and DVD re-release, courtesy of The Criterion Collection, as well as the 2017 Digital Cinema Package release in the U.K. The film’s thriving afterlife is particularly impressive considering it began in 1999 as an open-ended television pilot rejected by ABC. The French production company Studio Canal picked up the rights and granted Lynch the funding to shoot new scenes and give the pilot an ending, allowing him to release it theatrically as a feature film.[2]

This renewed interest in Mulholland Drive coincided with the 2017 return of Twin Peaks, the ABC series Lynch co-created with Mark Frost, about to return on Showtime after its aborted run on ABC from 1990 to 1991. The related publicity was already at fever pitch. Naomi Watts, the star of the film and a member of the new Twin Peaks cast, was more visible than ever. By the end of 2017, she appeared in four films—The Book of Henry (Colin Trevorrow, 2017), Chuck (Philippe Falardeau, 2017), The Glass Castle (Destin Cretton, 2017) and 3 Generations (Gaby Dellal, 2017)—and starred in the Netflix drama Gypsy (2017).

Among its many riches, Chris Rodley’s book-length interview with Lynch offers two bits of insight apropos of Mulholland Drive: 1.) Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) is one of Lynch’s all-time favorite films, and 2.) Warner Bros. approached him to direct a film based on Anthony Summers’s biography of Marilyn Monroe, Goddess (1985).[3] The Monroe project never materialized, but it did introduce Lynch to Frost, who would have written the script.

Both Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), the aging silent screen diva of Sunset Boulevard, and Marilyn Monroe, the 1950s “sex symbol” who died at 36 from a barbiturate overdose, share similar experiences with Mulholland Drive’s Diane Selwyn (Watts), an aspiring Hollywood star from small-town Ontario whose “wanting to act” leads to heartbreak and eventual suicide. As Julie Grossman concludes in her book Rethinking the Femme Fatale in Film Noir, “Sunset Boulevard and Mulholland Drive are particularly interested in the plight of women, as they reflect the cultural demand for, restrictions on, and destructive manipulation of the female image.” Further, she proposes that “Lynch is drawn to Monroe as he is to Norma Desmond and Diane Selwyn, because he is interested in women’s psychological responses to serving the Hollywood dream machine.”[4]

Lynch paid tribute to Sunset Boulevard with a shot of Norma’s Italian luxury car, the same 1932 Isotta-Fraschini behind the iconic Bronson Gate at Paramount Pictures, where Norma shows up on the set of Samson and Delilah (Cecil B. DeMille, 1949) expecting to be welcomed back into the studio that made her a star before Hollywood’s conversion to sound.[5] The official dedication, though, went to Lynch’s assistant Jennifer Syme, an actress killed in a Hollywood car accident at the age of 29, who had been in a relationship with star Keannu Reeves and was reportedly undergoing treatment for depression in the wake of the stillbirth of their daughter.[6]

Together with Watts’s active media presence, the latest attention surrounding the film affords an occasion to look at the diegetic and meta-diegetic functions of the film actress. This article revisits the film as an alternative to the critical theory and philosophy often applied to it. Instead, I take a more literal approach, pursuing the film’s own questions about the performer’s ontology (i.e., what s/he is).

In Hollywood films “about” film performers, one traditionally sees the actor or actress reified as an authentic subject through the labor, ambition, talent, humility, suffering, and price of fame in creating a character. The actress-character, a familiar trope in studio era Hollywood, achieved a level of “authenticity” through various ways: a casting type for star biographies; a belief in the real actress playing a version of herself in the actress-character; the historicization of the actress-character in real events and developments in Hollywood; and an ideology of success that accounts for what makes the actress-character a star.

Traditional female star narratives clearly demarcated the lines between the “authentic” actress in the diegesis and her manufactured doubles (her star persona and the roles she plays). Mulholland Drive upends the familiar trope of the aspiring or returning actress-character in films such as What Price Hollywood? (George Cukor, 1932), A Star Is Born (William A. Wellman, 1937), A Star Is Born (George Cukor, 1954), and Sunset Boulevard. I argue that the film uses the actress-character to interrogate the way Hollywood seeks to conceal performance from its very construction of authenticity, of what the audience accepts to be true, and the impossibility of the self’s existence outside the realm of performance.

Scholars have taken implicitly auteurist positions to examine performance in Mulholland Drive with respect to Lynch’s recurring ideas about theatricality and artifice. For example, building from her foundational work on Lynch, Martha Nochimson regards the female performer as a potent source of liberating creativity in an industry that drains its laborers of their energies. The Hollywood of Mulholland Drive is therefore another one of Lynch’s strange worlds that oppresses the generative and transformative powers of imagination.[7]

Viewing Lynch as a plastic artist, Justus Nieland situates the film’s performance moments within a designed media environment of interior spaces, while Todd McGowan interprets them by way of Lacan, elements of fantasy that lead a path to the Real.[8] Most recently, Richard Martin’s The Architecture of David Lynch discusses the urban geography of Los Angeles and the performance site of the stage, locations of popular entertainment and illusionist spectacle that alternately constrain and reveal possibilities for Lynch’s characters.[9]

Lynch’s achievements as an auteur are considerable, and the above scholars have made significant contributions to appreciating Mulholland Drive in the context of his worldview and directorial style. However, my concerns lie in the film performer as a distinct symbolic figure. Grossman addresses some of these issues, reading the film as a feminist rewriting of Hollywood noir that deconstructs the “femme fatale.” In the only sustained engagement with Watts’ performance to date, film critic George Toles closely analyzes the audition scene as a demonstration of the ways in which a film performer inspires faith in the spectator to believe the truth of what s/he sees (even under the most incredulous conditions).[10] Both Toles and Grossman, respectively, have paved a major inroad in dealing with the meta-cinematic mysteries of Hollywood acting and images of women that preoccupy the film. Following this road further along the film’s dark, winding curves, this article explores its representation of the actress as a role to be created and acted out.

Betty’s Adventures in Hollywoodland

The thematization of film acting in Mulholland Drive is not without historical precedent in experimental filmmaking. James Naremore’s authoritative book, Acting in the Cinema illuminates the ways in which classical cinema required actors and actresses to perform “an artful imitation of unmediated behavior in the real world.” “The actor,” Naremore explains, “is taken to be an already completely formed person who learns to ‘think’ for the camera.”[11] Modernist innovations in postwar art cinemas launched different rebuttals to this purported verisimilitude. Naremore refers to the blurring of theatrical and aleatory codes in Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960) as one example. According to Naremore, “Instead of treating performance as an outgrowth of an essential self, it implies that the self is an outgrowth of performance. ‘Performance,’ in turn, is understood in its broadest, most social sense, as what we do when we interact with the world—a concept embracing not only theater but also public celebrity and everyday life.”[12]

Rather than confusing the boundaries between performer, role, and spectator à la Breathless, Mulholland Drive thinks through the sociological problems of performance by turning to the film actress as a diegetic subject. If classical cinema insists that the film performer play a theatrical personage derived from the mimesis of an ostensibly transparent reality, films that represent actor- or actress-characters make the spectator hyperconscious of this presumed relationship between the self and performance. By contrast, Diane is an actress whose “wanting to act” is a desperate quest for personhood.

Watts enters the film playing a rising star, an archetype of Hollywood’s romantic, self-perpetuating mythology as both a “dream factory” and a “place where dreams come true.” Young, blonde Betty Elms (Watts) walks through the Los Angeles International Airport, beaming with wide-eyed wonder at the new city she simply “can’t believe.” A taxi chauffeurs her to a Spanish Colonial Revival courtyard apartment complex (singer and dancer Ann Miller, a veteran of studio-era musicals, plays the eccentric manager).[13] Betty’s Aunt Ruth, an actress on location in Canada, has lined up an audition for Betty and invited her to stay in her apartment. “I couldn’t afford a place like this in a million years,” she declares, “unless, of course, I’m discovered and become a movie star. Of course, I’d rather be known as a great actress than a movie star, but, you know, sometimes people end up being both!”

Hollywood is a land of opportunity dotted with palm trees and architectural gems, aglow in sunlight, and inhabited by celebrities. It is a “dream place,” in Betty’s words, a Hollywood that only exists in the movies. The helicopter shot of the Hollywood sign is less an indexical signifier of a physical place than an evocation of what the essayist Katherine Fullerton Gerould famously referred to as a state of mind.

Yet, Betty’s story seems to take place in a situation that could only be dreamed up in a movie. The female lead (Laura Elena Harring) in a film called The Sylvia North Story has gone missing after surviving a car accident on Mulholland Drive that interrupts an attempt on her life, but leaves her with amnesia. A syndicate run by the omnipotent Mr. Roque (Michael J. Anderson) takes over the film and stalls production, strong arming the director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) into recasting the part with an unknown actress named Camilla Rhodes (Melissa George), an insipid clone of Betty. Presumably responsible for orchestrating the botched execution, Mr. Roque possesses an inexplicably vested interest in Camilla’s casting.

The making-of Sylvia North storyline intersects with the Betty-in-Hollywood storyline when Betty discovers the missing woman in Ruth’s apartment. Hanging on the wall is a poster for the classic noir film Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). The woman borrows the name “Rita” from its star, Rita Hayworth, whom she vaguely resembles. Rita Hayworth herself was a persona Columbia Pictures created for Hispanic actress Margarita Cansino, whom the studio made over into a more Anglo-American star.

Motivated by a compassion for Rita and a curiosity about her past, Betty volunteers to help reconstruct Rita’s identity, an opportunity for the sort of role-playing an actress craves. “Come on, it’ll be just like in the movies,” she says eagerly to Rita before calling the police to inquire about the car accident. “We’ll pretend to be someone else.” With such idealism and guilelessness, Betty’s ability to act seems unfortunately improbable.

Lynch and Watts hold the depths of Betty’s talent in reserve, even during her rehearsal with Rita, but then show her transcend a script full of hokum. She practically transforms into “someone else” for her audition at Paramount. Betty’s astonishing performance is as much a revelation for the film’s washed-up producer, Wally Brown (James Karen), as it is for the casting agent, Linney James (Rita Taggart). In fact, Linney sees a more promising future in Betty’s career than in Wally’s tawdry melodrama. He decides to bring her to the Sylvia North set, where Adam is auditioning actresses lip-synching to vintage pop songs. Betty leaves abruptly, remembering her commitment to resume her detective work with Rita, but Adam has already picked Camilla for the role.

The sleuthing that Betty and Rita undertake leads them to the bungalow apartment of a woman called “Diane Selwyn,” whom Rita believes may be her real name. Diane’s mock-Tudor apartment is one of the “Snow White Cottages” in the Los Feliz neighborhood, where Disney animators lived during the production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937). Upon sneaking into the apartment, Betty and Rita do not find not a sleeping princess, but a woman’s body decomposing in Diane’s bed.

Horrified by the possibility that she was the intended victim or has been framed for a murder, Rita returns with Betty to Ruth’s apartment in the hopes of disguising herself from her pursuers. Betty makes Rita over into a blonde with a bob cut which resembles her own hairstyle. The attraction that has developed between the two women intensifies in the comfort they take in each other following this moment of trauma. They sleep together, but Rita awakens in a trance-like state and escorts Betty to a Latino subcultural performance space downtown.

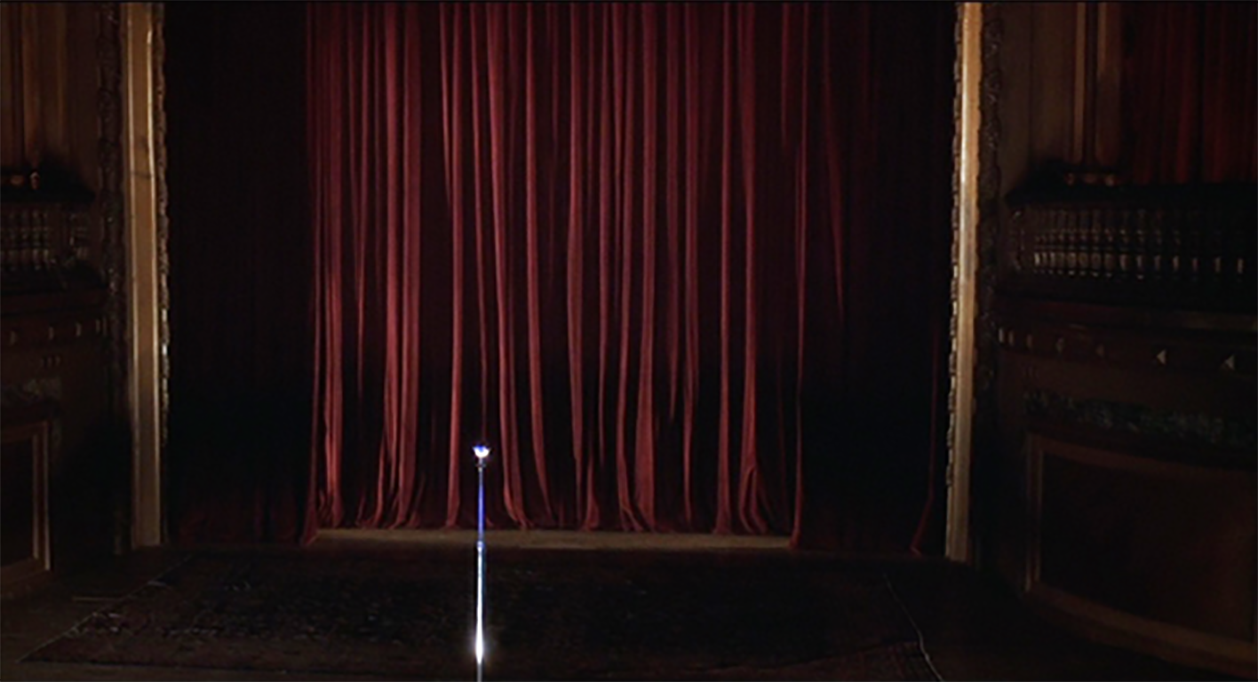

Neon lights spell out “Club Silencio” over a backdoor entrance; they at once beckon and forewarn. This Baroque Revival theater would be another metonym for the old-fashioned Hollywood dream were it not for the disruption of the white Anglo fantasy that transpires. In a virtuoso set piece that has elicited most of the critical commentary on performance in the film, Betty and Rita watch as a haunting magic act lays bare the disjuncture between performance and prerecorded synchronized sound that classical narrative cinema aims to hide.

Singer Rebekah del Rio lip-syncs her Spanish-language, a cappella recording of Roy Orbison’s love ballad “Crying,” moving Betty and Rita to tears despite their awareness of the mechanisms by which a live performance may be faked. It is appropriate that the interior of the Club Silencio is really the Tower Theatre on Broadway, which opened in 1927, the first movie theater in Los Angeles (and reputedly one of the first in the U.S.) wired to exhibit “talking pictures.”[14] The song continues even after del Rio faints onstage, or is this a performance of sudden death? Betty and Rita learn something that can only be apprehended through a theatrical presentation.

Mulholland Drive comes out of a long tradition of self-reflexive Hollywood films that purport to expose the behind-the-scenes system of star-making. In his book, Movies About the Movies, Christopher Ames maintains, “Cautionary tales about stardom end up glamorizing the phenomenon they are cautioning viewers about.”[15] The quintessential cautionary tales about stardom, What Price Hollywood? (1932) and A Star Is Born (1937), in part served as reactions to the “rags-to-riches” stories of “accidental success” in Hollywood popularized during the 1920s and 1930s, such as Harry Leon Wilson’s 1922 comic novel, Merton of the Movies.[16]

After Mary Evans (Constance Bennett) in What Price Hollywood? and Esther Blodgett (Janet Gaynor) in A Star Is Born are discovered, their rise to fame mirrors the decline of their male counterparts, Max Carey (Lowell Sherman) and Norman Maine (Fredric March), respectively. Ames insists that for the films’ efforts to demystify the star phenomenon, identification aligns with Mary and Esther, and real-life stars Bennett and Gaynor assure their ultimate success.[17] Both characters emerge as “strong individuals wrestling with the extraordinary demands of a larger-than-life existence,” he writes. He then adds that even if the films present another “rags-to-riches” myth, they “make that myth seem more truthful by placing that myth in another star’s tragic decline.”[18]

David O. Selznick was the producer of A Star Is Born and the executive producer of What Price Hollywood? Film historian J. E. Smyth finds that both films were products of Selznick’s nostalgic investment in telling Hollywood’s stories of its late silent and early sound eras that had recently passed. An aging member of those earlier eras, Selznick felt that the industry encouraged a competitiveness and reluctance towards invention that ruined the career of his father, producer Lewis J. Selznick. According to Smyth, Hollywood history films allowed Selznick “to face Hollywood’s failures, forgotten names, and the industry’s almost historical compulsion to make obsolete relics out of living film-makers.”[19]

Originally titled The Truth About Hollywood, and conceived as an autobiographical comeback vehicle for Clara Bow, What Price Hollywood? established a cycle of star biographies based on a casting type. This disguised representation of a series of historical persons in Hollywood reached its apotheosis in A Star Is Born. Esther Blodgett’s trajectory from extra to star may be unique, Smyth notes, but her story reminds audiences that Hollywood greats such as Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard, and Myrna Loy were also “pushed to stardom by chance and hard work.” Meanwhile, the studio promoted Gaynor as “playing herself” in the role.[20]

In addition to historical allusion and narratives of success and failure, another way in which Hollywood guaranteed the authenticity of the actress was through markers that distinguish her performance as somehow genuine. Accordingly, she is not acting but is whom she appears to be onscreen. Take, for instance, the 1954 CinemaScope musical remake of A Star Is Born. Film critic Richard Dyer posits authenticity as the prerequisite for star “quality” or “charisma,” in general, but identifies specific ways in which star Judy Garland conveys authenticity as Esther.

What makes Garland an especially complex case is the way the spectator can discern evidence of that authenticity in a triple-layer composite: Garland was one of MGM’s biggest stars and Esther is, of course, a film star herself, embodying an image manufactured by her studio with the new name of Vicki Lester. Quoting Dyer, “[the] film repeatedly indicates that stars are made by an elaborate process of production and manufacture.” He continues, “Yet while acknowledging the constructedness of stars, it is also wishing to assert that stars are real, that this star, anyhow (whether we’re thinking of her as Esther Blodgett, Vicki Lester or Judy Garland) is authentic.”[21]

In her solo number “The Man That Got Away,” Esther remains unaware Norman (James Mason) is watching her as she improvises with a group of jazz musicians in a nightclub after hours. Garland communicates a sense of spontaneity and privacy here coded as authentic. Esther’s immediacy of expression betrays a lack of expressive control. Garland’s overwrought performance style in the number, filmed in a long take, shows signs of what Dyer refers to as her “neurosis,” which audiences would have recognized by the mid-1950s.[22]

The apparent sincerity of the number makes it feel “real.” After fifteen years with MGM, Garland had not starred in a film since 1950 when the studio suspended her contract. She subsequently attempted suicide while battling alcoholism and drug addiction. A Star Is Born verified her authenticity—the natural talent and the “little something extra” Norman sees in Esther—as a comeback vehicle for her at Warner Bros. For Dyer, what is at stake in “The Man That Got Away” is “the authenticity of her capacity to sing.”[23] Esther gains a sense of coherence as an authentic self from the extra-cinematic knowledge that Garland’s star persona accords to the character.[24]

Unlike Garland in 1954 (or, for that matter, Gaynor in 1937 and Bennett in 1932), Watts was known only as an unknown in 2001. Her actress-character fails, whereas the real Watts succeeds in breaking into Hollywood. As Toles observes, “Naomi Watts was known to film audiences prior to Mulholland Drive, if at all, as a competent ‘background player’ (one whose job was to blend in rather than stand out). For that reason, Betty cannot draw extra definition and weight from our familiarity with an already established Watts persona.”[25]

Watts went on to enjoy box-office success in films such as The Ring (Gore Verbinski, 2002) and King Kong (Peter Jackson, 2005). She earned Best Actress Oscar nominations for 21 Grams (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2003) and The Impossible (J.A. Bayona, 2012). Indeed, the irony of Mulholland Drive’s fallen actress narrative is that the British-born Watts found her breakout role in the film after a brief acting stint in Australia and years of struggling to make it in Hollywood. This twist of fate stoked her publicity for the film, which frequently noted her parallels with Diane as an émigré actress who toiled in obscurity.[26]

The biographical parallels between the unknown Watts and the unknown Betty are not totally dissimilar from the way actress-characters derive their authenticity from extra-cinematic knowledge about the stars who play them. But without Watts’s career, persona, or body of work on which to draw, the film is unable to make Betty legible as anything more than an unknown. Betty does not exist in relation to an extra-cinematic biography so much as in relation to the persona of other stars we have seen before.

In lieu of Watts’s star persona, the film gives Betty purchase in the glamorous images of Hollywood past, but exclusively through signifiers of their personal style, not through historical or biographical referents. Watts has said that Hollywood blondes such as Doris Day, Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, and Tippi Hedren influenced her performance as Betty. The gray suit she wears to her audition certainly recalls the costume Edith Head designed for Novak in Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), another film about romantic obsession, female doubles, and the remaking of women’s images.[27]

Seeing Esther “become” Gaynor and Garland in the two versions of A Star Is Born, for example, concretizes the authenticity of the actress-character and the actress herself in a mutually-reinforcing process. Mulholland Drive produces no such effect because the performance codes are different. We believe Betty is an undiscovered talent with natural (almost magical) acting abilities, but she is only able to remind us of a Hollywood type (e.g., the “Hitchcock Blonde” as the stand-in for a woman in trouble). The artifice of costume, hair, and makeup is part and parcel of star production that Betty seems to embrace as naturally as her talent. The film never unmasks the artifice to reveal the actress behind the star, Betty (and by extension Watts).

Playing Betty in this affectedly anachronistic fashion also endows the character with the cheer of Paramount’s girl-next-door Betty Hutton and the pluck of the working-girl investigator in film noir, such as Betty Grable in Twentieth Century-Fox’s I Wake Up Screaming (H. Bruce Humberstone, 1941), both contemporaries of Rita Hayworth.[28] Whether Watts or Lynch had these other Bettys in mind is beside the point. This Betty is the girl: not because one can see Watts’s “essential” characteristics through her, but because one knows any number of Hollywood girls like her in classical-era films. Watts’s “big,” non-naturalistic performance is a masterstroke of stylization and control, portraying Betty as an earnest and endearing character who is also completely flat. In short, Betty is “just like in the movies.” Detached from any markers of authenticity, Betty only exists as an already performed self, comprised of well-known star personalities and character types.

The film extends its questions about performance from the diegetic and extra-diegetic levels to the meta-diegetic level. Just as Watts channels Golden Age blondes, Betty’s sense of being an actress relies on the way Hollywood studios packaged and sold images of its female stars. Phoning Ruth from her apartment after arriving in Hollywood, she announces, “I’m going to study those lines until I know ‘em inside out. Yep, either right here on this fabulous leather couch or I’ll take them with a coffee into the courtyard like a regular movie star.” Later, after rehearsing with Betty before her audition, Rita assures her that she is “really good.”

Betty imitates Greta Garbo’s signature Swedish accent and responds, “tank you, dahling,” miming a cigarette puff that sounds more like a kiss. Elements of a star’s mise-en-scène in preparation for a role—antique leather couches, coffee, cigarettes, and private Hollywood courtyards—are the exotic materials of a “regular” star’s publicity. This is the same publicity that promises Betty the chance of following in the footsteps of her accented idols to become both a great actress and a movie star. But her discovery is not to be, and the film goes on to recast Betty in the story of actress, Diane Selwyn.

Dreams, Movies, Performance

Mulholland Drive challenges the authenticity of the actress at various points of diegetic representation. Names are borrowed from other actresses (Rita Hayworth); performances will the actress into a nearly possessed state (Betty’s audition); bodies are ventriloquized by pre-recorded voices (the lip-synching at the Sylvia North audition and the Club Silencio); and characters are doubled by reflections (the mirrors in Ruth’s apartment), doppelgangers (Betty and Camilla, Rita and del Rio), and disguises (Rita and Betty). “I don’t know who I am,” Rita tearfully admits to Betty shortly after they first meet, to which Betty replies incredulously, “What do you mean? You’re Rita!” The actress is whomever she plays.

Of course, opportunities for actresses have been historically limited. Beginning with important books such as Marjorie Rosen’s Popcorn Venus (1973) and Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape (1974), feminist critical projects have chronicled the images of women produced in a male-dominated industry.[29] Laura Mulvey influentially argues about the traditional exhibitionist role for women in narrative cinema, whose passive bodies on display connote a “to-be-looked-at-ness” for an active male gaze within a heterosexual division of labor.[30]

Mulvey’s theorization is particularly relevant for thinking about female performer-characters. The recurring “device of the showgirl,” she asserts, functions to unify narrative and erotic spectacle by making the female body an object of the male gaze both in the diegesis and on the screen: “A woman performs within the narrative, the gaze of the spectator and that of the male characters in the film are neatly combined without breaking narrative verisimilitude.”[31] This gendering of visual pleasure is only one way to conceptualize the power structures that determine public perceptions of actresses.

More recently, media and cultural critics have begun pursuing what Su Holmes and Diane Negra term the “gendering of fame” and “the particular ways in which female celebrity is articulated.”[32] Holmes and Negra find that the media’s stories of purported struggles and failures of female celebrities “constitute ‘proof’ that for women the ‘work/life balance’ is really an impossible one.” Problems include “wardrobe malfunctions” and “upskirt shots”; aging and cosmetic surgery; public bouts with mental illness; drug or alcohol-related scandals; stages of “letting themselves go” physically; and veering “out-of-control,” emotionally or financially.[33]

Actresses are always cast in different roles, whether on the screen as characters in a film narrative or off the screen as “real people” whose private lives may be accessed through media accounts of struggle or failure. Within a patriarchal and capitalist system that profits from the sexual exploitation of women and the subjugation of their labor, the actress is obscured by her mediated and re-presented image, her double. Mulholland Drive emphasizes the pressures on the actress to be seen, compromising the nature of her image that publicly circulates. Acting is the only option available for claiming her body and identity for herself. Diane’s tragedy is not that she fails to “make it” in Hollywood, but that her professional failure as an actress impedes the process of self-fashioning necessary to reach those ends.

The Hollywood of the 1937 A Star Is Born is the last frontier, explicitly referred to as a “mythical kingdom of Western America” and “El Dorado for a new generation of pioneers.” The Hollywood of Mulholland Drive is more akin to the fallen Babylon of Sunset Boulevard. In their historical location of the actress, however, the films could not be more different. Film historian Robert Sklar groups Sunset Boulevard with other postwar films from the “‘Hollywood about Hollywood’ genre” including The Bad and the Beautiful (Vincente Minnelli, 1952) and the 1954 A Star Is Born. The films’ releases coincided with the crisis facing the industry brought on by the blacklist, labor disputes, dropping theater attendance, competition with television, and the Supreme Court’s 1948 anti-trust ruling against the studios.[34] For the first time, Sklar contends, Hollywood took stock of its present and potential future in relation to its past. Like What Price Hollywood? and the 1937 A Star Is Born, these films still told stories about “the fate of individuals rather than institutions.”[35]

Lynch has set Mulholland Drive in its contemporary moment, but the film contains no references to the film industry at the end of the twentieth-century, a fraught period of economic and technological change similar to the late 1950s. Rather, it constructs its Tinseltown out of architecture from the early years of the studio system (Ruth’s apartment, the “Snow White Cottages,” the Tower Theatre, the Bronson Gate). Its narrative is based on genres from the classical era (film noir, the musical, the “Hollywood about Hollywood” film, and even the children’s fantasy film[36]).

With citations of mid-century stars, acting styles, and character types, “The Betty Elms Story” might as well reside in the same retro “movie world” as The Sylvia North Story. That fictional film is a star bio-pic set in the 1950s and 1960s music industry, complete with recordings of Connie Stevens’s “Sixteen Reasons (Why I Love You)” and Linda Scott’s “I’ve Told Every Little Star.” Equating the film and the film-within-the-film does not give Mulholland Drive any more historical specificity, but implies that the “real” and the cinematic share the same space of performance. Compared to Mary Evans and Esther Blodgett (bright new stars of the Hollywood studio era), and Norma Desmond (the silent era star clinging to the vestiges of the old studio system in its decline), the figure of the actress in Mulholland Drive never coheres as a historical individual.

At the level of film form, the body of the actress is unstable. Until the Club Silencio scene, the film adheres to a conventional logic of narrative storytelling, albeit governed by the “paradigmatic structure” of commercial television. In that newer medium, a sequence of different storylines unfold and interrupt each other, but gradually interweave to form a collective continuity.[37] For the final twenty-five minutes of its 147 minute running time, Lynch replays events through a kind of looking glass, staging an alternate version of what has happened, swapping identities of characters, and re-contextualizing the meaning of Betty’s Hollywood adventures.

Lynch fills in certain burrows of the narrative warren—Mr. Roque’s syndicate is no longer present—only to plunge Watts’s character into a deeper rabbit hole through which she literally becomes “someone else.” Instead of Betty, the fresh, youthfully enthusiastic new actress in town with hidden talent, there is the depressed, possibly grieving Diane, a failed actress who was passed over for the lead in The Sylvia North Story. Instead of the director who loses control of his life and film, Adam Kesher is a slick Hollywood player.

Instead of Rita, the accident victim dependent on Betty’s help and affection, there is Camilla Rhodes (this time played by Laura Elena Harring), Diane’s cruel ex-partner who has found another blonde lover (played by Melissa George, Camilla in the earlier version). Camilla is also sleeping with Adam in exchange for career security. Their engagement party on Mulholland Drive turns into a night of devastating humiliation for Diane. Embittered by her rejection and jealous over her success, Diane contracts a hit on Camilla.

The first two thirds of the film are most commonly interpreted as Diane’s dream/fantasy that reflects both her unfulfilled desires (for Camilla, for a career as an actress) and her guilt over Camilla’s death, which drive her to madness and suicide in the film’s final, hallucinatory sequence.[38] Watts has indirectly supported this interpretation in her remarks on her performance strategies: “Everyone’s got a different interpretation of it. But I had to make something up for myself so I could make some solid, coherent choices. I thought Diane was the real character and that Betty was the person she wanted to be and had dreamed up.”[39] This interpretation speaks to Betty’s dual role in Diane’s wish-fulfilling fantasy: she is an ego ideal and a character she must play (an alter ego).

Audiences have acknowledged the way that in these last twenty-five minutes, the non-linearity of the plot and the discontinuity of the editing color Diane’s waking “reality” with a more nightmarish quality than the dream/fantasy section.[40] The accessibility of Betty’s dream/fantasy underscores the way the classical Hollywood style constructs a verisimilitude of action through narrative causality and the illusion of transparency. “Invisible” or unobtrusive techniques of mise-en-scène, cinematography, editing, and sound produce a clear space-time perception, which film historian Richard Maltby describes as “an apparently unimpeded access to the events of the plot and their meaning in the story.”[41] Film performance, he explains, contributes to that verisimilitude when performers “create the plausible illusion of a unified personality.”

However, the spectator experiences the performer’s presence in the same body as the character, which means that the performer must “disembody himself or herself to embody the role.”[42] Actors and actresses exists onscreen not only in a disembodied articulation, but also in “absent presence.” Their work is assembled by an editor from different shots; substituted by stunt artists, hand models, and doubles; and dubbed by vocal performers. Musicians perform a score independent from the actors and actresses, but help forge an emotional bond with these bodies viewed onscreen.[43] Viewing those bodies is not without ideological implications when the woman’s body bridges spectacle and narrative in the service of verisimilitude.

Hollywood cinema teaches audiences to accept a certain degree of truth in what they see and hear, not because they believe it to be real or it is necessarily realistic, but because it is plausible within a social and aesthetic construction of realism. From the shadowy crime syndicate to the L.A. apartment complexes full of secrets, Betty’s dream/fantasy is pure film noir—“the stuff that dreams are made of”—and yet the very conventions of Hollywood cinema suggest a basis in “reality.” Continuing Watts’s interpretation, Mulholland Drive literalizes the oft-repeated metaphor of cinema as dream, but for actress Diane, the dream is therefore a fantasmatic performance space in which she can “pretend to be someone else.”

As an amateur detective, a rising star recognized for her talent, and a woman bonded in romantic and erotic plentitude, Betty allows Diane to play the hero in her own film. Relative to the last twenty-five minutes, the verisimilitude of the dream/fantasy is consistent with the way scenes of embedded performance (Betty’s audition, del Rio’s singing) reach a heightened level of emotional truth. Betty’s rehearsal with Rita betrays the scripted contrivance at the heart of her audition, just as the display of dubbing at the Sylvia North audition and the Club Silencio pre-show undermine the liveness of del Rio’s voice.

Betty experiences both moments as expressions of genuinely felt emotion, first as an actress and then as audience member. The deconstruction of performance in the film never diminishes the impact of what Watts accomplishes. Diane’s dream/fantasy similarly reads as more “real” than the later section even if its meta-cinematic references and Hollywood conventions indicate it is “only a movie,” which is to say, “just a dream.”

Taking Diane’s dream/fantasy as a film of sorts, it remains inseparable from performance. Maltby goes as far as to claim that “[a] movie is a performance and not a text,” dating all the way back to early cinema’s illusion of moving bodies and objects within a fixed frame.[44] The word “cinema” derives from the Greek word for motion (kinema). The word “movies” derives from the industrial term “motion pictures,” to say nothing of the way the word “performance” may be used as a synonym for a film’s box-office profit, screening, and technological operation.[45] Lynch turns Mulholland Drive “inside out,” to quote Betty’s phone conversation with Ruth. The rising star narrative initially expected turns into the story of an actress who fails to sustain a reality and a coherent identity through performance, movies, and dreams.

Fragmenting and disembodying the actress in this way, Lynch links the construction of onscreen performance with the guise of self-presentation in society. In his forthcoming book Hollywood By Hollywood, Steven Cohan observes that traditional star narratives double the actress by twinning her with a star persona (e.g., Esther Blodgett and Vicki Lester) and matching her with a counterpart whose story comments on hers (e.g., Esther Blodgett and Norman Maine). Even in a postwar film such as Sunset Boulevard, the Gothic madwoman Norma Desmond is contrasted against the younger Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), a failed actress who reinvents herself as a script girl.

Cohan argues that this parallel structure allowed the studios to promote certain ideologies about stardom and success in Hollywood.[46] Although doubles abound in Mulholland Drive, Lynch eschews an overarching message about what makes or breaks a star. The use of doubles instead foregrounds the infinite possibilities of enacting a role, each wrought with its own pleasures and perils. Betty may be the more ideal version of Diane (the Vicki to her Esther), but Betty replicates Diane’s goal to become a “great actress,” something neither she nor Diane attains. Doubling in Mulholland Drive only represents the actress as an infinity mirror that reflects the human and social desire to land a part.

When a film such as the 1954 A Star Is Born demystifies the making of a star, a more “authentic” star triumphs over an exploitative industry to earn pathos and admiration (e.g., Esther Blodgett, or more accurately, Judy Garland). Scandal gossip of the postwar era informed the socially-determined standards of authenticity. As Cohan notes, Hollywood capitalized on the public’s appetite for fallen star narratives by producing a cycle of films that pulled back the curtain on the tragic life of fictionalized female stars. A film such as Sunset Boulevard hitched its fallen star narrative to a broader anxiety over the fate of the industry in its late studio era, while more nostalgic cautionary tales such as What Price Hollywood? and the 1937 A Star Is Born glamorized the female star by celebrating a certain casting type, recovering stories of early Hollywood.

Watts plays both the rising star of the 1930s and the fallen actress of the immediate postwar era, but the film’s unveiling of performance as film performance goes no further than doubling the character to authenticate the actress. She remains a floating signifier, impossible to see outside of the roles she must play. Against the backdrop of an ahistorical Los Angeles, Lynch brings her into focus through an association with the myth of the city, rather than with star biographies or Watts’ own persona. Beginning with its late nineteenth-century booster campaign sponsoring Southern California tourism and migration, a project Hollywood eventually took up in its films and star promotion, Los Angeles has been a model of self-invention. In a series of shots that end the film, Betty and blonde Rita appear in a montage of ghostly, overexposed close-ups, superimposed over a glittering urban sprawl beneath a midnight blue sky.

If any acting requires one to assume a social face to be seen in the world, stardom promises the ultimate opportunity. Shot in close-up, the Hollywood actress wears the mask of stardom that imbues her with expressive meaning for the movie going audience. These spectators view the face at a superhuman size, but nonetheless witness a recorded intimacy with a performance. Betty and Rita therefore eclipse Diane’s story in these last images, flickers of a hopeful, ecstatic dream. They “pretend to be someone else”; they literally merge with Hollywood. Betty’s pursuit of her elusive close-up acts out Diane’s dreams of success, giving the actress-character meaning in a new role to play (another actress), if only temporarily. The film then returns for a final time to the Club Silencio stage, now empty and silent. Betty and Rita’s giant close-ups have dissolved into the existential terror of un-being: the negation of performance, or the absence of a body in which to perform a self.

Author Biography

Will Scheibel teaches film and screen studies at Syracuse University, where he is Assistant Professor in the Department of English and serves on the adjunct faculty of the Goldring Arts Journalism Program in the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications. He is the author and co-editor, respectively, of two books on director Nicholas Ray: American Stranger (SUNY Press, 2017) and, with Steven Rybin, Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground (SUNY Press, 2014). Currently, he is writing a book on actress Gene Tierney.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Julie Grossman, who read a draft of this essay and encouraged me that I was on the right track. Through our conversations about Mulholland Drive (and her superb writing on the film), I was able to see things that no doubt influenced the ideas here. I also wish to express my gratitude to Steven Cohan, who allowed me to read and cite the manuscript for his forthcoming book, and to the Society for Cinema and Media Studies for the opportunity to present an abridged version of the essay at the 2018 conference in Toronto, ON.

Endnotes

“The 21st Century’s 100 Greatest Films,” BBC Culture, 23 August 2016, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160819-the-21st-centurys-100-greatest-films.

For a detailed account of the television-to-film adaptation, see Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, 269-271, 275-277, 279-286.

Chris Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, revised edition (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 71, 156.

Julie Grossman, Rethinking the Femme Fatale in Film Noir: Ready For Her Close-Up (London: Palgrave, 2009), 136, 141-142.

Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, 273. Lynch’s character on Twin Peaks, FBI Regional Bureau Chief Gordon Cole, was named after the Sunset Boulevard character working in the Paramount props department, who inquired about using Norma’s car.

Bill Hoffman, “Keanu Grieving Over Gal Pal’s Fatal Wreck,” New York Post, 5 April 2001, 9.

See Martha Nochimson, “‘All I Need Is the Girl’: The Life and Death of Creativity in Mulholland Drive,” in The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions, ed. Erica Sheen and Annette Davison (London: Wallflower Press, 2004), 165-181. See also Martha Nochimson, “Mulholland Drive,” Film Quarterly 56, no. 1 (Fall 2002): 37-45. For an expansion on the arguments of these essays, see Martha Nochimson, David Lynch Swerves: Uncertainty From Lost Highway to Inland Empire (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013).

See Justus Nieland, David Lynch (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012) and Todd McGowan, The Impossible David Lynch (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

See Richard Martin, The Architecture of David Lynch (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

See George Toles, “Auditioning Betty in Mulholland Drive,” Film Quarterly 58, no. 1 (Fall 2004): 2-13.

James Naremore, Acting in the Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 18.

Actress Lee Grant also shows up in a cameo as one of Betty’s neighbors. Grant had been blacklisted in the 1950s, but returned in the 1960s to star in both film and television, including the cult classic Valley of the Dolls (1967), another film about fallen actresses.

Christopher Ames, Movies About Movies: Hollywood Reflected (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1997), 22.

The novel inspired a Broadway play in its same year of publication, as well as film adaptations released in 1924, 1932, and 1947. The 1932 version was titled Make Me a Star.

J. E. Smyth, “Hollywood ‘Takes One More Look’: Early Histories of Silent Hollywood and the Fallen Star Biography, 1932-1937,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 26, no. 2 (June 2006): 181.

Richard Dyer, “A Star Is Born and the Construction of Authenticity,” in Stardom: Industry of Desire, ed. Christine Gledhill (London: Routledge, 1991), 138.

Dyer, “A Star Is Born,” 138-139. As often as we see references to Garland’s MGM career in the 1940s through her girl-next-door image, costume, performance style, and musical numbers in the films-within-the film, A Star Is Born also transfers her off-screen troubles to Norman. See also Wade Jennings, “Nova: Garland in A Star Is Born,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 4, no. 3 (Summer 1979): 321-37.

See also Richard Dyer, “Resistance Through Charisma: Rita Hayworth and Gilda,” in Women in Film Noir, rev. ed., ed. E. Ann Kaplan (London: BFI, 1998), 115-129. Dyer claims that Hayworth’s charisma as a star lends the otherwise unknowable Gilda a presence in the film as a figure of identification, particularly through movement (her hair toss and dancing). Discussing Mulholland Drive with Julie Grossman, she reminded me that it is this kind of authenticity Lynch’s actress-characters seek, something only possible through the dynamism of performance.

See, for example, Graham Fuller, “Naomi Watts, Three Continents Later: An Outsider Actress Finds Her Place,” Interview Magazine 31, no. 11 (November 2001): 132-137.

For more on the working-girl investigator, see Helen Hanson, Hollywood Heroines: Women in Film Noir and the Female Gothic Film (London: I. B. Tauris, 2007), 18-20. See also Philippa Gates, Detecting Women: Gender and the Hollywood Detective Film (Albany: SUNY Press, 2011).

See Marjorie Rosen, Popcorn Venus: Women, Movies, and the American Dream (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1973) and Molly Haskell, From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (October 1975): 11.

Su Holmes and Diane Negra, “Introduction: In the Limelight and Under the Microscope—The Forms and Functions of Female Celebrity,” in In the Limelight and Under the Microscope: Forms and Functions of Female Celebrity, ed. Su Holmes and Diane Negra (London: Continuum, 2011), 11-12.

Robert Sklar, “Hollywood about Hollywood: Genre as Historiography,” in Hollywood and the American Historical Film, ed. J. E. Smyth (London: Palgrave, 2012), 72.

Mr. Roque, a dwarf who sits in a curtained office, is both an Oz-like man behind the curtain and a wicked wizard of the West (whose endpoint is Hollywood), while Betty is the small-town girl lost in a “dream place.” Lynch has gone on the record about his love for The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), an intertext for his Wild at Heart (1990), leading one to assume these allusions to the film were deliberate in Mulholland Drive as well. See Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, 194-195.

See Warren Buckland, “‘A Sad, Bad Traffic Accident’: The Televisual Prehistory of David Lynch’s Film Mulholland Drive,” New Review of Film & Television Studies 1, no. 1 (November 2003): 131-147.

See, for example: Grossman, Rethinking the Femme Fatale; McGowan, The Impossible David Lynch; Nieland, David Lynch; and Toles, “Auditioning Betty.”

Richard Maltby, Hollywood Cinema, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003), 465.

See Steven Cohan, Hollywood by Hollywood: The Backstudio Picture and the Mystique of Making Movies (New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2018).