The Heterotopias of Todd Haynes: Creating Space for Same Sex Desire in Carol

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Using Foucault’s concept of heterotopia (an “other space”), this essay contends space is key to understanding Haynes’s Carol. It examines how Haynes, through his meticulous attention to framings, textures, color, and spatial relations, creates a queer counter space, time, and look—a rejection of early 1950s social and sexual propriety.

“What a strange girl you are, flung out of space,” remarks the title character of Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015), a film based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel about lesbian desire in the early 1950s. Carol (Cate Blanchett) initially makes this observation to Therese (Mara Rooney) during their first lunch, but she repeats the last part of this phrase, “flung out of space,” when the protagonists have sex for the first time. Space—the literal, the imagined, and the filmic—is key to understanding the film. Through his meticulous attention to the framings, colors, textures, patterns, and spaces, Haynes encourages viewers to consider what the space consists of, who occupies it, and in what ways.[1] We should also ask who is doing the looking and what is being seen in these spaces, both because of the centrality of the female-to-female gaze in the film and because same-sex desire in the early 1950s necessarily had to be occluded. Being (flung) out of space/place, having no space for “deviant” desire, suggests that the lovers will have to occupy “an other space,” what Michel Foucault terms a heterotopia. Heterotopias function, much as Haynes’s films do, to disturb sameness, to reflect the inverse of society, to subvert signification; they are the place of the other, the deviant.

The out-of-the-ordinary in Haynes’s film is a queer space and look (both in the sense of style and gaze)—that is, an anti-heteronormative rejection of early 1950s social and sexual propriety. In what follows, I first demonstrate how Haynes creates a series of heterotopias to tell the story. He does this initially by creating an other world of New York City in 1952 by drawing on images from urban photojournalists of the time, and then by inviting the audience to see that world through the aesthetics of cinematic melodrama, where the blocked, internal emotions are rendered visible through camerawork and color. Further, by staging the narrative during Christmas, Haynes produces a temporal disruption—“holiday time”—outside of ordinary time. Temporal disruptions are a signal feature of heterotopias for Foucault; he writes “Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time . . . heterochronies . . . a sort of absolute break with their traditional time.”[2] I show how these heterotopias (and heterochronies) are threaded throughout with a thematic conflict between entrapment/stasis and escape/change, evidenced on the narrative level, but more prominently through the mise-en-scene and specifically through the framing of characters. Finally, Haynes provides a glimpse of the heterotopia of female same-sex desire by foregrounding the female gaze. The film, then, is itself a heterotopia full of nested heterotopias mirroring and resisting, representing and neutralizing the no-space, no-place for same sex love in early 1950s America.

Foucault’s Concept of Heterotopia

Before turning to how precisely Haynes creates a heterotopic cinema, I will sketch out some of the essential features of Foucault’s concept of heterotopia. In his short lecture on heterotopia, entitled “Des Espaces Autres” (“Of Other Spaces”) (1967), Foucault names a number of “counter spaces.”[3] These include cemeteries, brothels, holidays (time that interrupts conventional work time), prisons, and American motels (a space, he claims, where illicit sex is both sheltered and hidden, where anyone can enter what is in fact a space of exclusion). A heterotopia, Foucault writes, is a “simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live.”[4] These counter-spaces are bound together because they are all outside of the ordinary, containing a disruption of time and space, which is most obvious in the cemetery where the dead absolutely rupture the time of the living. Foucault asserts heterotopias also “have the curious property of being in relation with all other sites, but in such a way to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect.”[5] That is, they evoke, even replicate, sites of normalcy while simultaneously calling them into question. For Foucault, a key example of a heterotopia is a mirror—both a “placeless place” (a u-topia, a no-place) and an actual site that disrupts our spatial position. Explaining the mirror as a heterotopia, he writes, “this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass [is rendered] at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.”[6] The mirror exerts a “counteraction” on the world that it reflects. [7] I would also add an emotional valence to heterotopias, because they are also “aporetic” spaces—spaces of doubt and loss—revealing contradictions in the very society in which they reside and contest.[8] Simply put, heterotopias challenge the order of things.

Haynes’s heterotopic cinema, likewise, challenges the temporal and normative order of things. As Dana Luciano astutely observes, Haynes’s films “typically bind dissident desire to temporal displacement.”[9] Haynes’s heterotopic cinema, then, is a kind of troping—a playing on and turning—of “straight” time and place. His cinema, as Luciano notes, “evokes the queer subject’s oblique relation to normative modes of synching individual, familial, and historical time.”[10] The heterotopic moves Haynes makes in Carol are in keeping with his other work, particularly Far From Heaven (2002), where Haynes conjures the cinematic space/time of Douglas Sirk and offers a non-ironic and refracted image of Sirk’s already distorted representation of an ostensibly hetero-normative, white middle-class 1950s America. In Carol, Haynes self-reflexively asks his audience to see the space and time of the film as an image of an image, an “other world” in another world, a queer heterotopia. This is a “twilight” world, to use a word often found in the lesbian pulp novels of the ‘50s to describe the liminality of the “twilight lovers” and “odd girls” who inhabited that genre.

Haynes’s Heterotopic Vision and Cinematic Melodrama

As Carol opens, the spectator enters a very specific heterotopic space of midcentury New York City, a reflection and disruption of a time and place. The film produces a melancholic vision of a “soiled” (Haynes’s word) city in time: 1952, just before the postwar abundance and brightness of the Eisenhower Era. Haynes wanted to use “the soft, soiled look of period photography”—rather than ‘50s cinema, with its dependence on the artifice of studio lighting and heightened color—to soften and tint the emotional content of the story. [11] This New York City is “real” because Haynes modeled the look of the city on actual images rendered by photojournalists and photographers like Esther Bubley, Helen Levitt, and Saul Leiter. During the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, these photographers produced serious-minded pictures of everyday people and objects on the streets of New York and other urban areas. But the image of New York City captured by these photographers is also an aestheticized naturalism, a stylized image of a (now) past time and place. As cinematographer Ed Lachman notes, these photographers were “documenting the urban landscape and experimenting with early color,” specifically Ektachrome film (which initially had a limited, less saturated, and cooler color range than film available today) to produce “an austere, soiled, muted look of naturalism.”[12] In order to replicate their vision, Lachman shot Carol in Super 16mm film stock to produce a palpable grain structure that suggests emotions below the surface of the characters. Lachman believes that film stock, because it is affected by exposure-time and can be manipulated by gels and other techniques, produces a depth which is unavailable in digital media so that even though we only observe the characters from the outside, the complex and layered visuals signal the turmoil within and beneath. As a whole, the film’s gritty, washed out colors, bleak spaces, and framings—which obscure and fragment the characters—foster the pervading sense that same-sex desire cannot speak and must remain beneath the surfaces. This aesthetic encourages the viewer to be attentive to spaces, objects, and framings, since that is how and where the characters and their desires are transmitted and revealed.

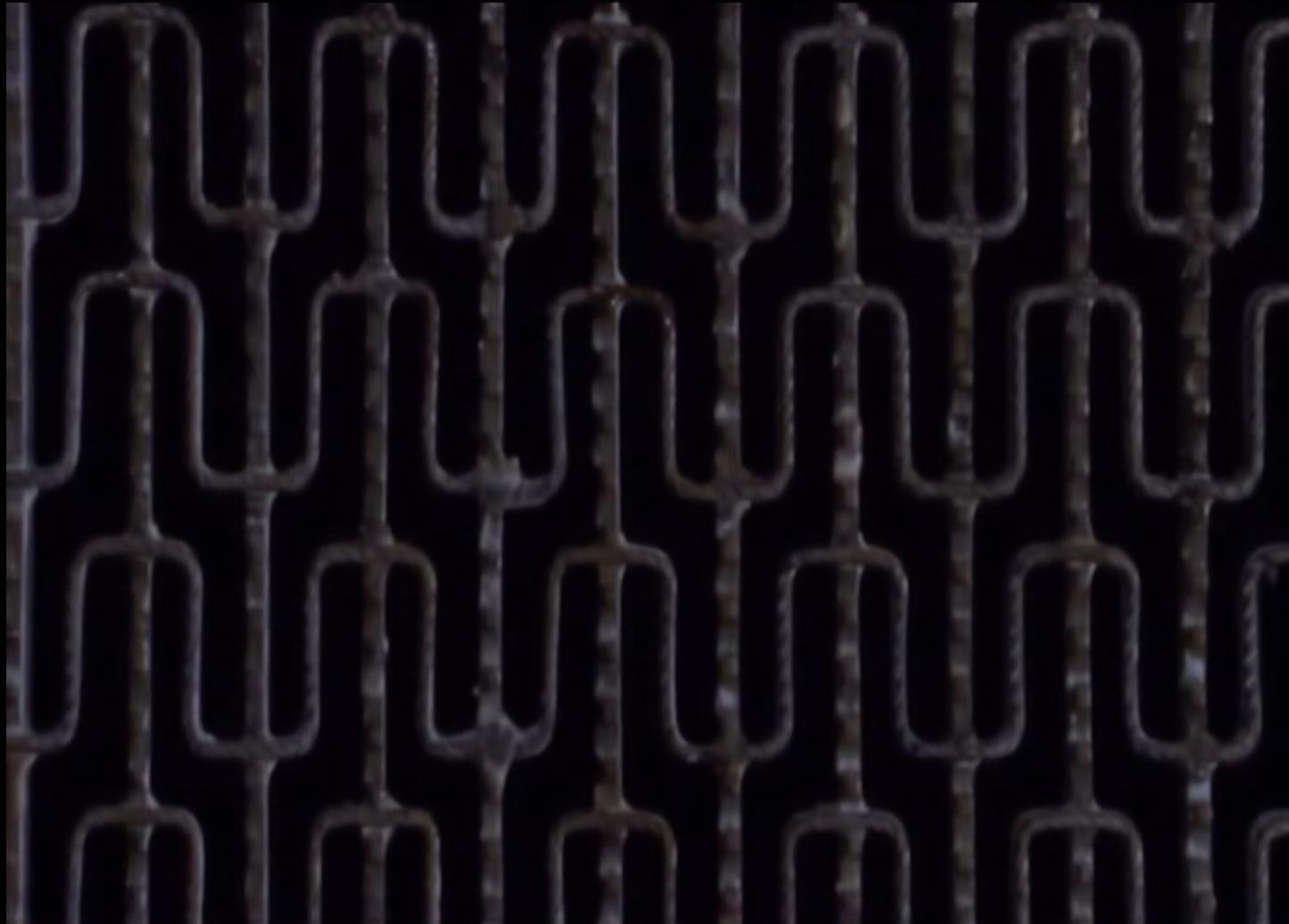

Haynes had a very precise idea of the kind of visuals he wanted to reproduce, telling an interviewer that this “New York was part of a different desolate time, a time of transition, marked by the scars of finding a post-war identity. The color palette and historical material we discovered registered this unique sort of dirty, sagging, sad place where anxieties could be felt.”[13] Haynes thus creates a distinct visual space—of dirty, dismal colors, and a bleak urban environment—that is inextricably tied to its time of post-war anxiety and transition. Fittingly, the opening shot of the film is of a metal subway grate in the gutter of a city street at night—the very subject matter of the street photographers mentioned above. However, the striking, latticed image that fills the entire frame is impossible to identify for the first few seconds. Rather, the image suggests a screen—something that hides and protects but also disguises. It conveys a beautiful but dark impression of blockage. Not until the camera tilts up across the latticed structure to a medium shot of feet walking can one contextualize and situate the image as a subway grate. Here, the disorienting visuals reveal and obstruct, and offer a static image that gives way to a sense of movement and transition (the moving feet).

Haynes’s scrupulous attention to the colors, costumes, props, and framing demonstrates he has internalized a fundamental characteristic of (‘50s, and especially Sirkian) melodrama: that the excess of feeling cannot be accommodated by the action, nor can those tormented feelings be spoken of. All must be displaced onto the mise-en-scene. For example, after the brief opening scene, the camera reveals Therese, her face shown through a rain-streaked and fogged car window, looking out on the city at night as she remembers, in extended flashback, the journey of her love affair with the wealthy, older, and married Carol. Here the narrative unfolds: it begins with their first encounter, where Therese was working as a shop girl at the toy counter of a New York department store during the Christmas rush; it continues on to a road trip out west, as Carol flees a messy divorce, and then to their eventual love-making and separation.[14] This shot of Therese through the car window fits a pattern for Haynes. As Mary Ann Doane suggests in an essay on his earlier work, this close-up of a woman at (or through) the window is a kind of signature shot for Haynes (and a stable trope of melodrama); it signifies the conflict, restriction, and pathos for women, who are often confined within a feminine domestic space.[15] Therese, here, seems trapped in time/in memory, moving forward in the car but caught in the past.

Throughout the film, Haynes deploys literal, imagined, and filmic heterotopias. First, he moves the protagonists and audience through the material other spaces of the New York imaged by photojournalists like Levitt and Leiter, as well as through the (failed) domestic space of the wealthy New Jersey suburbs where Carol lives: the car they travel in, and the liminal highways and motels that the two lovers travel as they try to find a place where their love can “be.” He then parallels those literal, placeless places of mirrors, hotel rooms, and cars with “being in love”—a concept, I suggest, that should be added to Foucault’s list of heterotopias, since being in love is both a real and an imaginary place, leaving one utterly alone, yet seeing and encompassing everything in relation to the beloved. Haynes explains that the “desiring subject” exists in a “tunnel of love”: a space that is cut-off from, yet in, the world.[16] Finally, in consistently framing the protagonists through doorways and behind shop and car windows, often shrouded in mist, dust, or rain, Haynes renders the characters impressionistically and provides a filmic heterotopia. By visually fragmenting and distorting the protagonists, he indicates their struggle against and within the social constraints—of marriage, heterosexuality, class, motherhood, and the unspeakability of same-sex desire—that entrap them. Spaces are not, as Foucault points out and as Haynes shows us, simply “voids” where “we place individuals and things,” but rather they are imbued with and reflect sets of power relations.[17] Space, in Haynes’s film (and perhaps in melodrama, generally) takes the place of speech.

As Foucault suggests, heterotopias do not only have a spatial dimension—disrupting and creating (other) space—but also have an unsettling temporal dimension. Haynes develops this heterochronia by having the bulk of the narrative, recounted in Therese’s flashback, begin a few days before Christmas and end on New Year’s Day. This is holiday time, a time outside of work and normal day-to-day activities, that ruptures normative time and offers a different time/place to be. Carol and Therese occupy this threshold of time, this time out of sync. However, Haynes goes further in this distorting of “holiday time” than simply placing the protagonists there; he offers a critique of the time itself. Conventionally and traditionally, the holidays are a “special” (i.e. positive) time/space for family, friends, food, and home. But Christmas can be, as Eve Sedgwick notes, also a depressing time—a moment when “religion, state, capital, ideology, domesticity, the discourse of power and legitimacy” all line up and speak with one voice.[18] Haynes, aware of the negative valence of holiday time for those who might not fit in this “happy” alignment of institutions, illustrates the restrictive nature of holiday time/space. First, he implies that the homes and Christmas activities/time that both Carol and Therese leave are traps—with Carol either altogether alone or confined to her husband Harge’s (Kyle Chandler) family’s house, and Therese either alone or forced to be part of her boyfriend’s family’s Christmas. Haynes then further inverts the traditional understanding of holiday time by showing Therese and Carol alone on the road, pointedly away from home, and all the confinement those homes entail during the holidays. Therese and Carol are isolated and anonymous, yet seemingly happy with each other in this inverse version of holiday time. At their first dreary roadside diner (on Christmas day), for example, there is a tracking shot from inside the diner of a deserted city street that moves past the diner’s store-front window, across a wall with bedraggled Christmas decorations, to the booth where the women sit, having soup and crackers. Therese stares out of the window at the empty street and tells Carol, “I could get used to having a whole city to myself”—a line which suggests a new way of conceptualizing the space (of Christmas time): a space where they can be together and yet away from the burdens signaled by the plastic Santa face on the wall and by Carol’s mention of home.

Trapped in Space

Running throughout the film is a tension between entrapment/stasis and escape/change—as hinted at by the film’s opening image of the subway grate and the framing of Therese in the car. At the broadest level, this tension plays out through the question: will Carol and Therese each remain within (or be caught in) the confines of heteronormativity and marriage, or will they find another place to be? Carol’s entrapment in (and struggle to escape from) her domestic space is most apparent in her interactions with Harge and his family in the wealthy suburbs. Though the couple is separated, Harge repeatedly tries to put Carol back in the domestic box of “my wife.” He barges into their former home unannounced, startling Carol (and Therese who is visiting); Carol, concerned about his abrupt entrance, asks what’s wrong. He answers, “Does there need to be a problem to visit my wife?” As the couple begin to argue over where their daughter Rindy should spend the holidays, with Therese observing, Harge turns angrily to her and asks, “How do you know my wife?” Harge’s desire to pin down Carol as “his wife” is underlined visually by Haynes showing Carol, in long shot through multiple doorframes, restlessly pacing around the enclosed space of the kitchen—a heterosexual domestic space she no longer wants to occupy, but is trapped in. Harge repeats the phrase yet a third time. In searching for Carol to force her back to his family’s place for Christmas, he visits Carol’s friend and ex-lover Abby (Sarah Paulson), declaring: “She’s still my wife.” Abby rightly points out the narrow space he has allowed Carol: “You spent ten years making damn sure her only point of reference was you.” Indeed, Carol is on the road with Therese to find a rather different reference point, as indicated by the cut from this scene with Harge and Abby to Therese entering Carol’s hotel room and handing the freshly showered Carol a sweater she has just lovingly nuzzled.

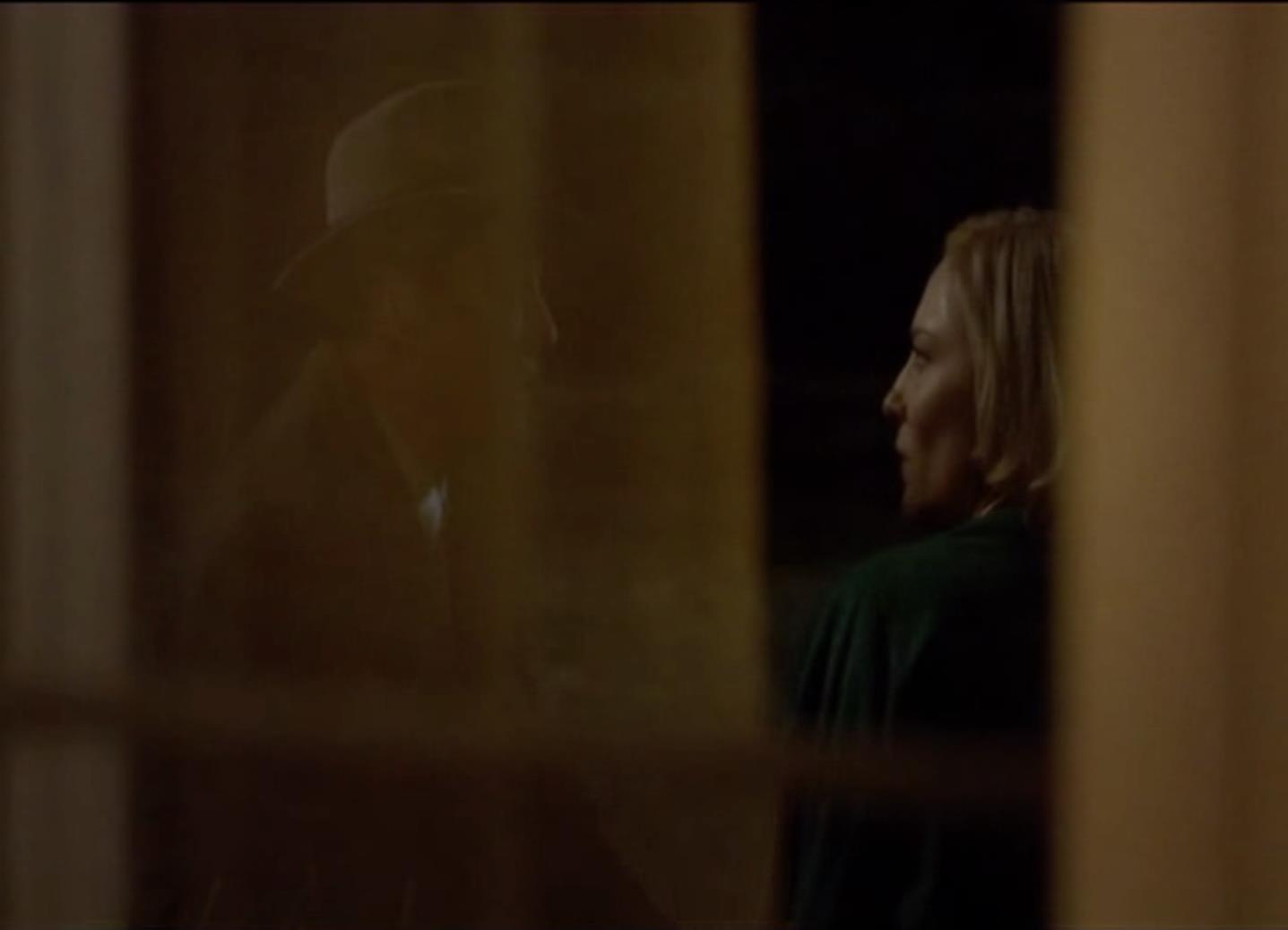

While Therese’s domestic space is less circumscribed than Carol’s—she does, after all, live in her meager apartment by herself—her boyfriend, Richard (Jake Lacy), consistently wants her to occupy the social and literal space he has contrived for her. This pressure occurs in nearly all of their exchanges. For example, he protests to their friends that Therese is “more excited by some chintzy camera than about sailing to Europe with [him].” He thus belittles her professional ambitions to be a photographer and suggests that what he has to offer—literally the same space to and in Europe, and figuratively his romantic space—is more important. This interaction is followed by his insistence that Therese stop by his family’s house for Christmas. Their final and most heated conversation occurs when Therese tells him she is going to go with Carol on a road trip and he accuses her of being in a “trance.” Asserting their coupledom, Richard tells her: “You made me buy boat tickets, I got a better job for you. I asked you to marry me, for Christsakes.” Resisting that heteronormative narrative, Therese replies, “I never made—I never asked you for anything.” As this argument takes place, the scene’s enmeshment in the threshold spaces of Therese’s apartment is visually striking; similar to Carol’s framing in the kitchen, Therese and Richard are in Therese’s apartment but are shot through doorframes and in hallways, cut off from one another and often obstructed from the spectator’s view—as well as each other’s. Further, they do not occupy a single room, but move between rooms while seldom being in the same room together in the shot. Thus, they are visually and emotionally isolated from each other, and seemingly neither speak the same language nor about the same romantic goals. Haynes captures his characters in space—literally and visually in the rooms they occupy, and figuratively in the social demands enclosing them. The framings of Therese and Richard and their fragmented and unfinished conversation—he leaves before she can explain—indicate the failure of their relationship and of Richard’s understanding of Therese. Space, once again, acts as a stand-in for language.

Haynes emblematizes the tension between stasis and escape for both women, even at the level of props. In their first meeting at the toy counter, Carol asks Therese for a specific doll for her daughter. When Therese tells Carol the store is out of stock, Carol then inquires what sort of doll Therese wanted when she was a little girl. She replies that she wasn’t interested in dolls and wanted a train set, then points Carol to a beautiful, hand-painted, limited edition set across the room. Haynes emphasizes Therese’s “caughtness” in this encounter when she tells Carol she would show her the train, but “I’m sort of confined to this desk.” The doll, and its associations with little girls, motherhood, and stereotypical female gender roles, stands in contrast to the more stereotypically masculine train set with its connotations of freedom and movement. However, this prop is more complicated than simply indicating escape, since the train does move, but only in a circle—caught on the tracks provided. Haynes explicitly links Carol to the train and its possibility of movement in Therese’s flashback by providing a close-up shot of the toy train speeding along the tracks, which then cuts to Therese looking at Carol looking at the train. Similarly, Haynes shows the absolute immobility that Carol must also fight. Like the beautiful train, Carol remains trapped on the tracks of heteronormativity, perversely moving but going nowhere. An almost throw-away line refers to the imposition of immobility, after Carol is back from her trip west and she is stuck having endless and stultifying meals at her snobby, upper-crust parents-in-law’s home in the hopes of seeing Rindy, who has been removed from her custody. Carol tells Abby after one of these encounters: “What more can I do? How many more tomato aspic lunches just to come home every night without [Rindy]? To this [gesturing around at her empty home].” The tomato aspic seems a fitting metaphor for what Harge and his family wish for Carol—to congeal her in a particularly class-inflected and empty domestic space.

A Melancholy Escape

Though one might imagine that the “escape” Therese and Carol make as they take to the road in Carol’s car would begin to open up new relational, sexual, and other possibilities, Haynes renders their road trip rather ambivalently. On one hand, like many road movie protagonists, Carol and Therese are seemingly free of the oppressive norms of domesticity, work, and conventional social values—at least as imposed by outside forces. They share the spaces of the car, the hotel rooms, and eventually each other—though with little conversation along the way and virtually no discussion of desire. In doing so, they create different kinds of space. On the other hand, in their muted interactions on the road, there remains an air of menace, of unspeakability, as if the tentacles of home and heterosexuality invisibly follow and poison their escape. As Patricia White observes: “The sense of surveillance pervades the film formally . . . even before the detective is introduced, images are often partially blocked as if viewed by someone in hiding.”[19] Of course, the penetrating power of the patriarchy (with its attendant rule of law) is made literal as the detective (whom Harge has hired to follow them) drives a device through the other side of their hotel room wall to record their sexual union. Thus this road trip, this other space Carol and Therese occupy, remains enmeshed in, even intruded on, by the very social relations they seek to escape. Haynes underscores this hierarchy by allowing the road trip interlude to last only 20 or so minutes of the film’s 118 minute run time.

Closer examination of the literal spaces the women inhabit on their trip—the car, the hotel rooms—reveals further evidence that their traveling dislocation in space, while subversive and disruptive since they can choose when, where, and how to be, is nevertheless still accompanied by a sense of desolation, trauma, and repression—which I suggest is a function of the somewhat melancholic nature of Haynes’s aporetic heterotopia; it remains a space of loss even while it calls into question the confining nature of heteronormativity. The car, in Carol, functions in part like the ship Foucault describes in his discussion of heterotopias; for him, the ship is a positive space, full of dreams and adventures travelling from place to place, a passage to and through other heterotopias.[20] However, the promise of the car as a vehicle of dreams is undermined by the landscape through which they travel: a dead and forsaken Midwest in winter that is filmed in a muted and limited color palette, which production designer Judy Becker describes as “dirty,” and the often shabby places where they end up. There are no sweeping vistas of America’s vast heartlands, no sense of the possibilities of the open road, no exciting urban areas full of difference. Haynes emphasizes this bleakness early in the trip by lingering on a shot of a decaying cornstalk and dark, spindly weeds as the car passes by. Further, the majority of the shots of Therese and Carol in the car are through the window rather than from inside, suggesting a kind of entrapment in the midst of freedom; also, the audience is often not privy to any conversation they may be having. Even when they are shown within the enclosed space of the car, the two are often shot singularly, not in a two-shot, indicating that each remains apart from the other, hermetically sealed in her own unspoken world of desire and located precisely nowhere.

The cinematic and actual separation between the two women lessens as they begin to share hotel rooms. At a drab, run-down motor inn in Canton, Ohio, they take the rather ironically named presidential suite at Therese’s insistence; she wants to share the suite rather than take two separate rooms—a signal of her growing desire to literally merge into the same space as Carol. In the suite, they are finally both in the frame, seated closely together on the floor with Carol happily and intimately applying make-up to Therese’s face and then asking her to lean in and smell perfume on her wrist. Protected and hidden from the world (they think), they are also excluded from it. In the next hotel they occupy, the much more luxurious Drake Hotel in Chicago, Therese remarks on the expensive fabrics and furniture in the room and stares longingly at Carol. At the Drake, “home” once again reasserts itself; Carol phones home, but does not speak when Harge answers and then lies to Therese about what she was doing. Therese, too, is reminded of home as she picks up several letters from Richard. In spite of its potential for intimacy, Carol and Therese do not consummate their relationship in this richly appointed hotel, suggesting that the Drake—with its aura of upper-class, implicitly normative heterosexual respectability (the very thing Carol is fleeing)—is not a place for them.

Like the shots of the dismal landscape through which they travel, the motel room where they eventually do have sex is a dreary, unattractive place. The setting and mise-en-scene of their eventual consummation seem to reflect the contemporary cultural condemnation of “perverse” desire and the need to keep this kind of love on the periphery, rather than in a beautiful (both literally and metaphorically) room in a more tolerant and vibrant metropolitan center. Indeed, they finally have sex shortly after midnight on New Year’s Eve in another depressingly ugly motel room (lit in sour green and yellow tones) in the small town of Waterloo, Iowa. The location of this motel and the colors of chartreuse and yellow remind us that this film originated from a lesbian pulp novel, a genre known for its lurid covers and “dirty” content. As Amy Villarejo notes in her complex and compelling discussion of the status of these pulps for us today, the world of the pulps was one that trafficked in “the tropes of torment, shame, sin, lust, and shadows.”[21] Scriptwriter Phyllis Nagy seems aware of this particular residue and weight of the midcentury lesbian pulp past when she tells Terry Gross that this kind of motel was essential to her conception of how and where their love could be in their “life on the run.” Nagy felt it was important to highlight “the very mundane details of that motel room—not a great, grand hotel room—and the fact they're surrounded by the detritus of their lives.”[22] Rather than a moment for a new beginning and a greater intimacy, they are weighed down by the disintegration of their lives as lived in New York and haunted by a sense of isolation.

In this climactic scene of lovemaking, Haynes films the women initially as mirrored reflections. Therese sits before a vanity mirror and Carol stands behind her with her hands on Therese’s shoulders; the audience sees them in the mirror in an over-the-shoulder shot of Carol as she looks at both herself and Therese. The mirror is (here again) a heterotopia, a kind of disruptive, placeless place; it suggests their love exists, but has no place or is displaced. The reflection in the mirror also indicates a distancing or distortion, a slight removal from the real, and a kind of duplicity insofar as their love can both be and not be in the ‘50s world in which they live. As Carol tells Therese that she and Harge never spent New Year’s Eve together, she touches her hair, and Therese responds by touching her hand and saying “I’ve always spent it alone. In crowds. I’m not alone this year.” With these confessions, they kiss and the camera finally moves from their reflection in the mirror to focus on the couple themselves as Therese says, “Take me to bed.” This moment is one of the few times Carol and Therese speak overtly of their desire until the end of the film, and the cut from reflection to origin suggests the two are now speaking plainly. As these brief sentences indicate, there has been a struggle throughout the film between silence/the unspeakable and direct communication, a variation of the conflict between stasis and escape. As Haynes notes, “love itself makes you feel at a loss for language,” and this loss, coupled with the sense that their desire must be spoken of obliquely (and sparingly), helps explain the relative silence of the film. [23] Throughout the film there is only sparse dialogue, consisting of indirect, incomplete conversations, or shots of characters shown talking but not heard by the audience.

In fact, Nagy seems at pains to show just how hard it was in the early 1950s to articulate or even describe lesbian desire generally. For example, in a scene that precipitates Carol’s road trip, Carol’s lawyer tells her she cannot see her daughter because Harge has petitioned the court for sole custody of Rindy on the basis of a “morality clause.” When Carol asks “what the hell does that mean?” the lawyer responds only with the name “Abby Gerhart” (Carol’s ex-lover) without any mention of homosexuality or lesbianism. This unspeakability of desire also recurs in two phone calls between Therese and Carol. In one, Therese tentatively wonders whether Carol wants her to “ask her things”—to which Carol pleads “Ask me things, please.” But the nature of these “things” remains unspoken. Only the tight close-up of Carol rather desperately holding the receiver and smoking nervously suggests that she longs for a deeper and more erotic connection. In the other phone call, which occurs after the two have separated in Carol’s effort to salvage some sort of visitation rights with her daughter, Therese calls Carol and says only her name—but Carol remains silent and eventually hangs up. The dissonance between what is felt and what can be spoken of was signaled early in the film in a scene where Therese and Richard are with a friend in a movie theater’s projection booth, watching Sunset Boulevard’s (Billy Wilder, 1950) climactic New Year’s Eve scene, depicting Norma’s (Gloria Swanson) profession of love and Joe’s (William Holden) rejection of her. The friend explains, when asked what he is writing as he watches the film, “Right now I’m charting the correlation between what the characters say and how they really feel.”

Claiming Lesbian Desire

The film does articulate lesbian desire through Haynes’s focus on the intricate nature of the gazes and sightings between the two protagonists, particularly Therese’s literal framing of Carol when the camera takes the former’s gaze. While Harge wants to box Carol into his idea of heteronormative domesticity, Therese wants to frame the older woman in (and surround her with) her own nascent lesbian desire. At the very outset, Therese stares at Carol in the toy department and seems to frame her there in time/place, right above the train set; then, in long shot, Haynes shows us Therese’s staring. In their next meeting—a lunch in a midtown restaurant—Therese looks intently at Carol (and Carol does on occasion gaze back directly). However, it is not until Carol picks Therese up to take her out to her suburban home that Therese is able to fully indulge her looking pleasure. As Carol stops to buy a Christmas tree, Therese first looks at Carol through the car windshield (itself already a framing device) and then pulls out her camera and begins to take snapshots of Carol, freezing her in time/space and desire. We see the results of those photos when Carol visits Therese’s apartment; Carol looks over various photos on the wall, and then lingers over a photo of herself (Blanchett looking stunning) and pronounces it “perfect.” This photo is of Carol, in her mink coat, in medium long shot at the Christmas tree lot, standing sideways, head turned, looking directly at the camera. Carol seems pleased that Therese has captured an image of herself that she wanted to project—beautiful and alluring, with a desiring gaze. Clearly, Therese’s looking is hardly one-sided; Carol has her own forceful gaze, objectifying, sexualizing, and desiring a woman she wants to possess, when she first sees Therese in the toy section. During their conversation about the doll and the train set, Carol looks intently at Therese and finally says, “Well, that’s that. Sold.” While the “sold” refers to the train set, Carol’s smile and the camera (which holds Carol’s look on Therese) suggest Carol is sold on, and perhaps trying to buy, something more.

However, what Carol also “buys” at the counter—Therese, their road trip and sexual union, that “other space” they could exist in—she gives up in exchange for one last attempt at motherhood and conventional respectability. In order to try to have some sort of access to Rindy, she submits to the tedious meals with Harge’s family mentioned above, seeing a lawyer, and seeing a parents-in-law approved, high-priced psychotherapist. In a dramatic custody battle scene (Blanchett’s biggest scene) with Harge and their respective lawyers, Carol demands that her voice be heard. She asks “Can I speak?” as the lawyers bicker about the admissibility of the investigator’s evidence, the reports by her psychotherapist that her “aberrant behavior” was largely a result of Harge’s mistreatment, and the claims that she will now make a suitable mother. Visually, up to this point in the scene, Carol has been shot from behind as we get over the shoulder shots of the lawyers and Harge, making clear that they and their law, courts, families, and medical experts—not her—are really at the center of this dispute. The framing then changes to a set of medium shots of Carol finally standing up for herself and claiming her queer, heterotopic space by doing three things. First, she rejects that her relationship with Therese was “aberrant” (her own lawyer’s word), saying instead she “wanted it” and “will not deny it.” Next, and most dramatically, she gives up the fight for custody of her daughter. Finally, she physically stands up in the scene and tells them: “There was a time when I would have locked myself away—done most anything just to keep Rindy with me. But what use am I to her. . .to us. . . living against my own grain?” Carol’s declarations throughout this scene form an extraordinary rejection of the heteronormative, the maternal, and the imposition of the legal and medical discourses that would name and bind her behavior. She counters narratives of homosexuality as disease; she refuses the law’s approval of her now non-aberrant motherhood; and, most poignantly, she gives up her actual daughter, instead claiming a mutually inclusive space for herself and her desire. Carol’s action here also complicates a trope of maternal melodrama. Like Stella (Barbara Stanwyck) of Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937), she gives up the daughter she loves, but, unlike Stella, she claims a life for herself rather than only for her daughter.

The Ending: An Ambivalent Heterotopic Mirror

The film shows Carol powerfully rejecting her status as well-to-do suburban mother and wife and all that goes along with it. However, it is less clear, through both the narrative and visuals, what Therese wants or how she sees herself. Shortly after this meeting with the lawyers, Carol asks Therese out for a drink one evening, despite the fact that she has not seen nor spoken to her in several months (it is April now). This is the same tense scene that opens the film, though in the first iteration we do not hear what they are saying, and so do not know the meaning of meeting. Only near the end of the film when the scene is repeated does the audience finally know what is said. In the conversation, which is filled with awkward silences and barely-alluded-to changes in their lives, Carol asks Therese to come live with her; Carol has gotten both a job and an apartment in Manhattan. Though disconcerted, Therese is distant and refuses Carol’s offer with a flat, “No. I don’t think so.” Carol then tells her where she will be for dinner later in the evening if Therese changes her mind. Finally, Carol tells her directly, “I love you.” Therese does not respond, and they are interrupted by a friend of Therese’s, making the whole interaction even more awkward. With this open declaration of love, Haynes moves us to yet another sphere where love dares to speak its name openly (at least for Carol); he also no longer visually distorts nor blocks the character, in contrast to much of what has gone on before. Yet Therese appears unable or unwilling to respond to Carol.

The differences between these two “same” scenes evoke a heterotopic moment in space, where this seemingly ordinary interaction between two women that begins the film is replicated yet refigured with pain, loss, and longing in the second instance. Indeed, the two scenes that bookend the film act as a kind of mirroring device, forcing us to “see again” the women and their desires, rather than remain voyeuristically outside—in the orderly world of the young man who interrupts them and whose point of view the camera initially shares. In the first scene, the camera focuses on the back of Therese’s head as Carol leaves; in the second, we instead see Therese’s face, her uneven breathing, and her panic as Carol touches her shoulder and says goodbye.

After having rejected Carol’s offer, Therese leaves the bar and steps out into the dark, literally and figuratively, and gets into a car on her way to a friend’s party. There, in a series of shots, Therese is once again framed in doorways and through windows, darkly lit and in green tones. The framing and color tones here suggest that Therese remains locked in or behind a space where she cannot express her desire. At the party, she receives admiring flirtation from Genevieve Cantrell (Carrie Brownstein), whom she rebuffs, but her interaction with Genevieve seems to trigger a moment of self-reflection. Therese takes a moment alone in the bathroom, thoughtfully smoking a cigarette, and then decides to leave the party and find Carol. Our final image is of Therese walking across a crowded restaurant toward Carol in slow motion as the two exchange gazes.

On one hand, this seems a clichéd scene—both in terms of the visuals and in terms of the seemingly “happy ending.” But on the other hand, this ending remains suffused with loss. Carol has claimed another space for herself, but at the cost of her daughter; and her tentative younger lover might again change her mind. In short, the film Carol has indeed presented an other-place. However, it is, like the heterotopic mirror, also a no-place. The place the protagonists claim, in the end, is not an unambiguously liberating space—as Foucault’s examples of heterotopic spaces (the cemetery, brothel, and prison) remind us. Therese and Carol’s world will, for many decades to come, remain confined to an Ektachrome vision with its limited color palette, and, by extension, its limited social choices.

Author Biography

Victoria L. Smith is Associate Professor in the Department of English at Texas State University. Her work has appeared in numerous academic journals—including PLMA, Genders, and the Quarterly Review of Film and Television—and covers topics ranging from Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood to the films Boys Don’t Cry and Monster and the television series Dexter. Her research interests include queer studies, film studies, and cultural theory.

Notes

Doane has likewise noted how crucial space is to understanding Haynes’s work. Mary Ann Doane, “Pathos and Pathology: The Cinema of Todd Haynes,” Camera Obscura 19. 3 (2004): 1–21.

Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16.1: 26.

Foucault coined the term “heterotopia” to distinguish real sites from utopias which he understands as unreal spaces. The term is derived from the Greek heteros, “another” or “different,” and topos, “place.”

Peter Johnson. “Unravelling Foucault’s ‘Different Spaces,’” History of the Human Sciences 19.4 (2006): 80.

Michiel Dehaene and Lieven de Cauter, Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society (New York: Routledge, 2008), 25.

Dana Luciano, “Coming Around Again: The Queer Momentum of Far From Heaven,” GLQ 13.2-3 (2007): 250.

Haynes, quoted in Iain Stasukevich, “A Mid-Century Affair,” American Cinematographer 96. 12 (2015): 55.

“Ed Lachman Visually Elicits Emotions Below the Surface of the Characters in Carol | Graphic Communications,” accessed August 14, 2016, http://motion.kodak.com/kodakgcg/motion/blog/blog_post?contentid=4294992893.

Robert Goldrich, "Todd Haynes," Shoot 56. 5 (October 23, 2015): 11 & 29; Business Source Complete, EBSCO (accessed August 14, 2016).

For a thoughtful discussion of Carol as a “masterpiece of the melodramatic imagination” and as an homage to film history, see Walter Metz, “Far From Toy Trains,” Film Criticism 40.3 (2016): 1-4.

Nick Davis, “The Object of Desire: Todd Haynes Discusses Carol and the Satisfactions of Telling Women’s Stories,” Film Comment 51. 6 (2015): 32.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Queer and Now” in Donald E. Hall and Annamarie Jagose (eds.), The Routledge Queer Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 2013): 6.

Patricia White, “Sketchy Lesbians: Carol as History and Fantasy,” Film Quarterly 69. 2 (2015): 14.

Amy Villarejo, Lesbian Rule: Cultural Criticism and Value of Desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 161.

Phyllis Nagy, interview by Terry Gross, “In ‘Carol,’ Two Women Leap Into An Unlikely Love Affair,” Fresh Air, NPR, June 9, 2016, http://www.npr.org/2016/01/06/462089856/in-carol-two-women-leap-into-an-unlikely-love-affair (9 June 2016).

Joe McGovern, “Carol,” Entertainment Weekly, no. 1377/1378 (August 21, 2015): 58.