At the Margins of the Bromance: A Queer Reading of The Hangover Part III and Its Promotional Materials

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract:

The “queerness” of the bromance has drawn much attention, yet analyses of the ways these films facilitate queer readings paratextually is lacking. Examining The Hangover Part III and its paratexts, this article elucidates the centrality of queer possibilities to both the bromance film and its marketing.

In his edited anthology dedicated to the bromance film, Michael DeAngelis highlights the inherent paradoxes of the cultural phenomenon that underpins the genre.[1] The bromance, he writes, “has come to denote an emotionally intense bond between presumably straight males who demonstrate an openness to intimacy that they neither regard, acknowledge, avow, nor express sexually.”[2] As this definition indicates, the bromance must tease the possibility of sexual subversion, whilst also containing said potential and maintaining the hetero-masculinity of its protagonists. The Hangover Part III and its promotional materials provide an opportunity for examining these tensions and teases in closer detail, highlighting some of the ways that the bromance can be marked by reactionary politics whilst also serving as a vehicle for queering hetero-masculinities. Whilst the bromance’s potential to queer may typically focus on the content and form of a film or franchise, one of the compelling ways that the bromance’s alternative ideologies can come to the fore is via the paratextual. Paratexts offer opportunities to target niche audience sectors and to explore queer possibilities, resisting the narrative containment often used to neutralise subversion within a film and to appease the centre and right. Presenting analysis of some of the more innovative ways that The Hangover Part III was marketed, I argue that the bromance’s paratexts present particularly rich areas for analysis.

The Complexities of the Bromance

Given their emphasis on homoerotic relationships between men, “on the surface at least, bromances promise opportunities for gender subversion and seem to offer richly heterodoxical possibilities.”[3] DeAngelis situates the bromance as part of a larger “cultural shift” that “has undoubtedly signalled a broader acceptance of nonheteronormative cultural expressions.”[4] However, as DeAngelis cautions, it “would be problematic to posit such acceptance as an indication of any broad-based, unqualified panacea of a lingering cultural homophobia.”[5] Peter Forster expresses similar reservations, observing that “While the bromance genre obviously capitalizes on – admits to- the recent attention to masculinity and male sexuality in popular culture, it also definitively reacts against – denies – the idea of gayification.”[6] The way that this denial is played out, or the manner by which gender and sexual subversion are disavowed by the bromance, may be seen to thwart meaningful room for progressive representations. The bromance “tests the limits” of a culture’s “acceptance of sexual difference.”[7] Of course, in its testing of limits, the bromance can also be seen to consolidate the existence of limits, and in so doing reaffirm gender and sexual boundaries in conservative ways. One of the common ways that heteromasculinity is reaffirmed by the bromance is via the presence of women. Women and the domestic space are both used commonly by bromances to reaffirm sexual boundaries and restore the protagonists’ heteromasculinity come the film’s conclusion.[8] The Hangover franchise epitomises this; all three films feature weddings, events that may be seen to regulate or contain the vulgarity and homoeroticism that dominates each film prior to its matrimonial conclusion.

Thus, whether or not the bromance film can genuinely foster queer understandings of sexuality and gender, or a more nebulous queer quality, is muddied by its inherent paradoxes. For DeAngelis, bromance “qualifies as queer in that it renders heteronormativity strange.”[9] This measure is consistent with David Halperin’s articulation of queer as that which “acquires its meaning from its oppositional relation to the norm.”[10] If queer is understood as a “positionality vis-à-vis the normative,” as “whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant,”[11] then the relationships between men explored by bromance films present as particularly rich for queering. This queering can be understood two-fold: bromance films queer relationships between men and masculinity, albeit it in ways that are often veiled by comedy and irony; but they also present opportunities to be queered by critics, to have their attempts at containing homoeroticism via hetero-matrimony or union problematized or challenged. Halperin’s definition of queer highlights the positionality of the critic, and the role that they may play in queering the bromance. For instance, a bisexual, or nonmonosexual, perspective facilitates substantial epistemic possibilities for re-reading or queering the bromance. Read bisexually, the notion that reaffirming a male character’s attraction to women at a film’s end adequately serves to disavowal his previous homoeroticism loses its legitimacy. If we assume that a heterosexual resolution dispels or renounces homoeroticism then we risk overlooking the potential of nonmonosexuality within bromance narratives, thereby reifying a binary understanding of hetero- and homosexuality at odds with a queer framework.

With homoerotic relationships between men, most of whom are, have been or hope to be married to a woman, its focus, the bromance is marked by pronounced bisexual possibility. Both Beth Roberts and Maria San Filippo have identified the specific connection between the genre and bisexuality. In fact, Roberts argues that “the evolution of the bromance in the 2000s has played a significant part” in shifting the cultural visibility of bisexuals in recent years.[12] She notes,

In creating a space for same-sex desire among ostensibly straight men, the bromance suggests that sexual orientation may not always be defined by what you do and whom you do it with. This stance makes the bromance especially well suited to the imaging of bisexuality because of what it implies: that sexual identities have to do less with the desires and behaviours we exhibit than with the ways we make sense of them.[13]

San Filippo asserts that the comic qualities of the bromance also make it a particularly “conducive vehicle for the articulation of bisexuality”[14] and an opportunity for queering heteronormativity. Because bromance films are “liberated from the responsibilities of realism, [their] comedy can venture beyond the confines of everyday conventionality, so as to defamiliarize the compulsory monosexuality that governs our logic of desire.”[15]

In addition to the genre’s potential for subversion, to queer hetero-masculinity, blockbuster bromances must also appease, or avoid alienating, more conservative viewers. Thus, at the same time that comedy can facilitate the transgression or defamiliarizing of gender and sexual conventions, it can also function more conservatively. In her analysis of The Hangover, Heather Brook observes that when gender norms are transgressed in the first film “the result is disordered and unattractive, but ‘funny’.”[16] Focussing on the feminization of Alan, Brook argues that “any transgressive potential inherent in his character is ‘managed’ and defused as humour,” meaning, ultimately, that Alan’s unconventional masculinity poses no real threat to the heteronormative social order.[17] Whilst comedy facilitates Alan and Chow’s unconventional performances of masculinity throughout the franchise then, it also confirms the characters’ deviance and abnormality. As a consequence, some of the transgressions of compulsory monosexuality presented in the film are rendered problematic by their comical reification of hegemonic masculinity and heterosexuality. Whilst the comical treatment of subversion does not necessarily contain or fully-defuse queer potential, acknowledging the comical function of gender and sexual transgression is crucial to tracing the more reactionary facets of The Hangover franchise. It also provides a useful lens for reflecting on some of the ideological shifts that can be traced throughout the films.

The Hangover Part III

The third film in the franchise and focus of this paper, is largely consistent with Brook’s critique of the first film. In Part III, the exhibitionism that viewers have come to expect of both Alan and Chow continues. For instance, a shirtless Alan digs a grave and Chow’s penis is exposed in the film’s final sequence. The confidence and comfort that these characters demonstrate in their nudity amongst other men is part of their camp otherness and contrasts with the portrayal of Phil, the Wolfpack’s “alpha male,” who remains fully clothed. Alan and Chow are the characters we laugh at, not with, largely because they are marked as other against the films other male characters. Part of this humour stems from the pair’s failed masculinity, or feminisation. The multitude of exposed women throughout the first two films can be seen to reflect and heighten Chow and Alan’s alignment with femininity. Read through a monosexist lens, the objectification of female bodies throughout the first two films may also allay homoerotic anxiety on the part of both the male characters and viewers.

However, these issues noted, the third film can be distinguished from the previous two instalments in ways that provide greater opportunity for subversive readings. Firstly, The Hangover Part III does not allay homophobic anxiety with exaggerated female nudity or the promise of heterosexual nuptials like the earlier films did. In fact, bare breasts are entirely absent from The Hangover Part III – a remarkable contrast to the rest of the franchise. Alan and Chow also take on more prominent roles in The Hangover Part III. Alan, in particular, the break-out star and fan favourite of the first two films, becomes the narrative’s central figure resulting in some structural divergences from the earlier films. Unlike the flashback structure of the first two films, where the Wolfpack recount the misadventures of a bachelor party and meet the deadline of a wedding, the third film is structurally distinct. The Hangover Part III does not revolve around matrimonial preparations; instead, it begins with a funeral. After his father’s death, Alan’s family stages an intervention to deal with his increasingly outlandish behaviour (the latest casualty of his antics being a deceased giraffe). Alan agrees to attend rehabilitation on the proviso that his Wolfpack reunite and escort him to a rehab facility in Arizona.

Significantly, The Hangover Part III is also bereft of a looming wedding. This absence heightens the homoerotic potential between the protagonists who are neither celebrating a bachelor party (and thus heterosexual masculinity) nor working together to ensure the accomplishment of marriage (and thus heterosexual maturity). Instead, The Hangover Part III begins with the death of one of the franchise’s patriarchs, Alan’s father. Rather than being concentrated on a bachelor party gone awry, as the first two films are, The Hangover Part III sees the Wolfpack enacting an intervention and escorting Alan to rehabilitation. From the outset, then, the film is focused on facilitating Alan’s reclaiming of self-determination and independence rather than heterosexual monogamy. In keeping with the first two pictures, the film ultimately concludes with a wedding, when Alan marries an equally awkward pawnshop owner named Cassie. However, the film’s post-credit sequence actively undermines any stability Alan’s nuptials might suggest.

Throughout the franchise, closing credit sequences serve to destabilise matrimonial stasis and offer viewers a parting chance to indulge in the hijinks of the Wolfpack. Rounding out each film in this way, the franchise can be seen to celebrate the perverse. Yet, the post-credit placement of these sequences may be seen to lessen their threat to each film’s heteronormative conclusion. Of the use of photographic montages during the credits of The Hangover, Lesley Harbidge writes:

The prominence given to these moments, not least by ensuring that the images from Stu’s camera are the very last things they, and we, see, might undercut any easy reinstatement of the status quo and complete negation of male camaraderie. Indeed, and exactly as in the sequel, the succession of images that features in the closing credits sequence of The Hangover captures the men, and their bodies, at their most grotesque and liberated.[18]

Playfully violating the ostensible conclusiveness of matrimony, these closing sequences privilege the debauchery and journey of the characters over the stasis of marriage. Yet, this violation is undercut by its framing as a flashback; the photographic montage presents glimpses of the past, the lost chaos that preceded each film’s wedding. The third film in the series does not continue the concluding photographic montage tradition. Instead, in a more disruptive challenge to the heteronormative maturity and stasis of marriage, the film concludes with a sequence depicting the morning after Alan and Cassie’s wedding. In a clear ode to the morning-after sequence of the first film, Alan, Cassie, Stu and Phil wake up together in a Las Vegas hotel room. The closing sequence reveals that the traditional wedding night consummation has been replaced with a raucous night akin to an extended bachelor party, completely destabilising expectations of matrimony in favour of an image of polyamory and sexual fluidity.

This final sequence suggests the Wolfpack’s behaviour has not changed and seemingly never will, with the principal exception that at the conclusion of the film and the franchise a woman has been invited into the fold. For instance, Stu and his new breasts lend the sequence a notably queer inflection by destabilising easy distinctions between sex, gender and sexual orientation binaries. The emergence from the master bedroom of Chow, who has demonstrated his penchant for bisexual group sex throughout the franchise, lends the scene strong orgiastic implications. Indeed, orgies are suggested throughout the franchise as a whole in less pronounced ways. As Harbidge observes of the first film, it is the Wolfpack’s insecurity about what may have passed between them during the hours they cannot recall which makes them most awkward and paranoid with one another the morning after.[19] In contrast to the previous films’ photographic montages, and retracing of the men’s steps, The Hangover Part III does not offer any answers to what has transpired the night before. Instead, the franchise’s closing frames revel in a suggestive scene of polymorphous perversity. As a consequence, queer connotations are not as readily undermined or disregarded by the film’s structure or narrative. Although regressive homophobia, sexism and racism certainly exist throughout the franchise, the conclusion’s refusal to right sexual transgressions or restore stasis is subversive and challenges the monogamous monosexuality that might be anticipated in these films. Arguably all of the films in the series emulate this in their celebratory photographic montages. However, in the third film this excess is not contained as a flashback, pre-dating matrimony, but instead as an extension of the narrative’s linear progression. The Hangover Part III continues the franchise’s exploration of homoeroticism and masculine performativity on screen. However, it also diverges from the first two films by withholding a sense of stasis that would neatly defuse this eroticism at its conclusion.

Yet, while this sequence follows the film’s matrimonial conclusion, its location after the credits position it at the border of the text, within the realm of the paratextual. In contrast to opening or title credit sequences, which have been theorised at length, closing credits and post-credit sequences are a less examined paratextual facet.[20] If the opening credits guide us into the diegetic world then the closing credits guide us back into the real world, signalling a rupture or departure from the filmic world.[21] Because it is positioned at the margins, simultaneously within the temporality of the film’s narrative but also beyond the closing credits, this sequence’s subversion might be understood as less disruptive. It exists in a space for play after the film’s matrimonial obligations have been fulfilled and may therefore seem less likely to offend or divide viewers. Just as comedy may be seen as a less threatening means of transgression that ultimately holds the potential to challenge heteronormativity - the playfulness of the film’s paratextual terrain may also facilitate interesting possibilities. The paratextual realm provides greater opportunity to present uncontained queer meanings because it is not contained by the film’s reactionary or defensive narrative impositions. It is marked by flux, ambiguity and greater nuance.

Promoting Queer Possibilities

Promotional materials provide opportunities for exploring this idea further, particularly given that they provide opportunities to target particular demographics in novel ways. Marketing texts are fundamentally designed to appeal, yet they must also navigate boundaries in order to avoid alienating potential viewers. The promotion of The Hangover Part III evidences the need for diversification within a campaign. The official trailer and primary poster used to promote the film, which targeted a mass audience in cinemas and on billboards, adhered largely with the reactionary ideologies of the films. For instance, the film’s poster conveys an emphatic image of heteronormative masculinity, albeit presented in a comical way. Dressed in sharp suits and dark sunglasses and approaching the viewer with stern and serious expressions, Stu, Alan and Phil gaze directly at the camera. The serious expressions and body language on this poster are likely to be read as ironic by those familiar with the franchise. Alan’s awkward stance in the background of the poster suggests humour and singles him out as the character with the least convincing performance of masculinity, a focus of humour throughout the preceding films. The poster’s emphasis on masculine performativity and comedy indicates that the film will deliver what audiences have come to expect of The Hangover franchise. Similarly, the official theatrical trailer for the film emphasizes the franchise’s ongoing fascination with and repulsion for homoeroticism. For instance, the trailer includes a sequence in which Chow instructs Alan to kiss him: “hey fat stuff, quick, give me some sugar!” When Alan obliges, a cut back to Stu and Phil watching from the car reveals their disbelief and puzzlement, as Stu asks worriedly: “Did he just kiss him?”

Figure 2. Official trailer for The Hangover Part III

However, the film was also promoted using a range of texts that are void of this type of containment or winking to the camera, texts which provide room for more subversive readings. One of the strongest examples of this is “Alan’s Facebook.” In keeping with Alan’s characteristic sciolism, the “Facebook” is in fact a Tumblr page (http://alansfacebook.tumblr.com). The decision to produce this marketing text using the Tumblr platform, rather than Facebook, seems significant given Tumblr’s reputation. Whilst there are vast opportunities for “users to create more nuanced labels for themselves than simply ‘male’ or ‘female’ and ‘straight’ or ‘gay’” on the internet broadly, Abigail Oakley observes that “the unlikely, somewhat quirky environment of Tumblr has provided fertile ground for just this type of terminological evolution.”[22] Since its inception in 2007, Tumblr has become known as a safe space for queer expression and boasts a rich and expressive queer community. This high visibility of queer expression grows partly out of the site’s reputation and community, however Tumblr “is not just quirky due to the people who use it but also because of the distinctive features and affordances... that shape the way [it] is used, the type of information shared there, and the kind of communities encouraged to gather there.”[23] Digital Media Management, the company tasked with creating the “Alan’s Facebook” marketing text, cites the franchise’s quirky characters and their relationships as inspiration. Opting to utilise the Tumblr platform seems a natural progression of this tactic. Visitors to “Alan’s Facebook” are greeted by an “in-world” experience,[24] which transgresses fictional boundaries, inviting them into Alan’s world – or Alan into their own lives. On the Tumblr page, reblogged images and memes from real users’ Tumblr pages commingle with fictional posts from Alan, including childlike crayon illustrations and edited photographs. The page effectively captures the unusual, childlike and camp aspects of Alan’s character. More than merely capturing Alan’s character, though, the page itself contributes to his characterisation both through its posts and “Alan’s” responses to questions submitted by fans. When a fan asks, “Hey Alan, what’s your favourite colour?,” for example, the answer is “Mauve obviously!”

The potential queer meanings of Alan’s camp peculiarities are particularly heightened in the online space of the Tumblr page, which presents a variety of posts with queer connotations. These include stills from Magic Mike, infamous for its sexualisation of male bodies and queer following, with images of Alan photo shopped onto Channing Tatum’s body or into the frame beside him. Images of cupcakes, butterflies, and a gif (moving image) of a shirtless man thrusting his pelvis as rainbows erupt from his groin are also featured. These posts magnify the more subtle references to queer culture made by Alan in the first two films, making his ambiguous sexuality more salient. Along similar lines, his erotically charged relationships with Chow and Phil are also reflected on the Tumblr page. In one of a series of letters scrawled in crayon to Chow, for instance, Alan includes a sketch of what he terms his “best friend,” Phil. The image is tagged with the caption: “Phil’s hair even looks good in my drawing!” Another illustration of Phil is accompanied by the caption: “Even as a drawing he’s just so darn handsome!” Alan’s admiration of Phil is undercut by his childlike naiveté, another characteristic exaggerated by the Tumblr page, as well as his (misguided) identification with Phil’s “alpha male” qualities (including his muscular physique, physical toughness and womanising). Nevertheless, homoeroticism between the two characters remains evident both within the film and on the Tumblr page without the type of conservative reactionary shots that mark its inclusion in the trailer and film itself.

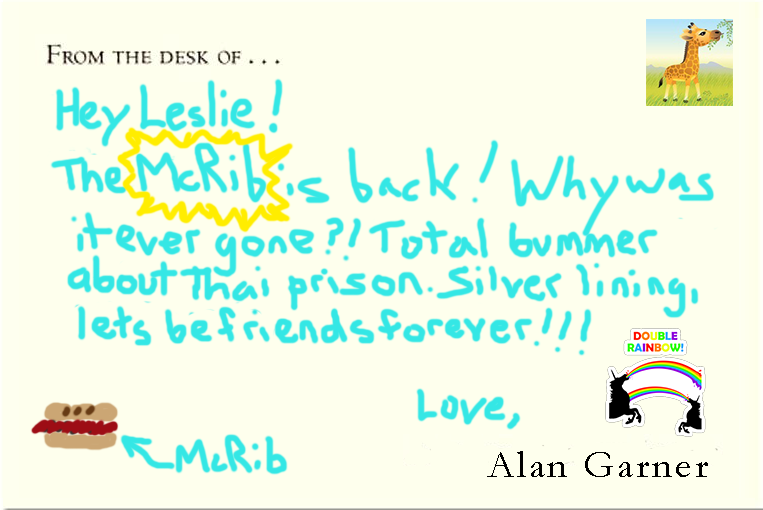

Insights to Alan’s relationship with Chow can also be gained from “Alan’s Facebook.” For example, visitors to the site learn that since the action of the second film and Chow’s imprisonment in a Thai jail, Alan has sent him a cat poster, a series of illustrations, and an update on the return of the McRib. He has also befriended a Nigerian prince who promises $50,000,000 and Chow’s release from prison. The miscellaneous posts on “Alan’s Facebook” draw on details from the existing films, but also elaborate on Alan’s character and his relationships. Marked by eccentricity and polysemy, the Tumblr contributes to characterisation by magnifying Alan’s idiosyncrasies, including his close and unconventional, potentially romantic bonds with Chow and Phil. The Tumblr page offers a unique mode of characterisation because it exists in a temporal format that allows users to engage with the posts as frequently and in any order that they wish, without entailing resolution or containment. This disruption of the conventional narrative and viewing temporality associated with cinema further lends itself to a nonmonosexual reading in that it abnegates closure and fosters ambiguity.[25] Thus visitors are offered the power to read the posts in queer ways without impediment.

The potential eroticism of Chow and Alan’s relationship is also made salient in one of the official posters used to promote the film. Centring on the relationship between Alan and Chow, this poster depicts an intense intradiegetic gaze between the two male characters. A tight frame on Chow and Alan’s faces depicts them gazing into each others eyes, as Las Vegas burns to the ground in the distance behind them. Neither Alan nor Chow meets our gaze as viewers, and thus we are invited to reflect upon their proximity and suggested relationship. The fact that this poster does not clearly correspond to a scene or moment from the film imbues it with further significance and ambiguity, offering viewers the chance to interpret the poster as they please.

Two distinct interpretations are likely to be prompted by such reflection. A heteronormative reading of the poster might suggest Chow and Alan gaze at one another as rivals. In this case, one might assume the destruction of Las Vegas in the background is part of the aftermath of their battle.

An alternative, equally plausible reading might interpret Chow and Alan’s gaze as representing not rivalry but another type of intimate relationship. That Alan’s brow is slightly furrowed may suggest annoyance or a sense of yearning or smouldering desire. The proximity of the men’s faces, lips aligned, along with the ease of their expressions suggests intimacy. With blood and debris across their temples, the city burning behind them, the scene is set for a goodbye kiss, or perhaps a celebratory embrace of their survival. This may suggest that the mayhem and antics of the franchise will ultimately lead to the union of Chow and Alan, characters who have both been marked as other and out of sync with the world around them throughout.

Chow’s peculiarities were further emphasised in promotion of The Hangover Part III, most notably via the “Chow Mouth!” app. Created as part of The Hangover Part III marketing campaign, the app was available for free download in app stores and promoted on the film’s official website. In contrast to the bizarre but innocent ramblings of “Alan’s Facebook,” the app enables users to select from a collection of Chow quotes from the films. Once a quote is selected, an extreme close-up of Chow’s mouth, which users are encouraged to hold in front of their own, appears and relays the selection. Unlike the awkward, but ultimately naïve, offerings at “Alan’s Facebook,” users of the Chow app are presented with a list of crude quotations to choose from such as: “I’ll give you anything. You wanna fuck on Chow? I’ll make fuck with you right here. Take you to Chinese paradise. I’ll nibble on your balls,” “Chow used to be on top of the world. I had whores in all zip codes!” and “I can’t feel my nuts. Would you rub them and make sure they’re ok? Then I can splooge. Thank you. Oh Aah. Thank you.” As these examples reveal, the joke of the app is consistent with the film’s characterisation of Chow as being crudely open about his sexuality and speaking broken English in a stereotyped Chinese accent. Both the app and film problematically position Chow as both the sexual and racial Other. The grotesque close-up of his soft chin and chipped teeth used by the app further render his characterisation as abject, not harmlessly offbeat like Alan. Although fans of the films may recall the context of these sexually charged quotations, in the app many of Chow’s remarks have unclear reference points and can be directed at anyone, regardless of gender. This emphasises Chow’s sexual fluidity whilst also encouraging users to partake in their own ambiguous play with the app. In addition to emphasising his hypersexuality, the app also makes Chow’s aggression and villainy salient. While the app’s reliance on humour may be seen to defuse Chow’s sexual subversion as comic fodder, its emphasis on play and its lack of resolution or normative containment lend it greater potential for transgressive readings.

Fig 6. The “Chow Mouth!” app in action.

A number of the promotional materials accompanying the release of The Hangover Part III can be understood to heighten or, at minimum, facilitate a queer reading of the film, particularly the characters of Alan and Chow. As discussed, this stems, in part, from the formal conventions and reading practices made possible by interactive texts such as the Chow Mouth App and the “Alan’s Facebook” Tumblr page. Yet the queer potential of the film’s marketing texts can also be attributed to their bi-suggestive content. This latter consideration, in particular, raises the potential for concerns that the film’s marketing is exploitative and potentially bi- or homophobic. But these texts and concerns can also provide a springboard for considering the centrality of bisexuality and queer potential to film marketing more broadly - both in terms of visual pleasure and polysemy, as well as temporality and reading practices. Put simply, the marketing of The Hangover Part III highlights the ways that the commodification of bisexual desire may prove lucrative for commercial cinema.

Tackling this issue in her book The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television, Maria San Filippo argues that mainstream films are often promoted using “a mode of queer commodification that mobilizes bisexuality to appeal to a queer audience without threatening straight spectators.”[26] Accordingly, many marketing texts may possess an inherent queerness, or at least a greater potential for queer readings and pleasures than many narrative films, which have traditionally been more likely to impede queer readings with their conventions, such as coupled resolution. The Hangover Part III and its paratexts signal interesting ways that blockbuster bromance films may capitalise upon the polysemy and pleasures of promotional texts in ways that facilitate greater potential for queer readings. Moreover, this example signals that the extensive, and expensive, marketing campaigns of such films - which may include multiple sets of posters, trailers, apps, and websites - may be well-suited to developing and shaping queer meanings because of their potential for polysemy, participation and placement within niche settings, such as Tumblr. While the texts discussed here are far from exhaustive, they indicate the significance of paratexts to understanding the rich queer potentiality of the bromance genre as well as the textuality of contemporary films more broadly.

Author Biography:

Chloe Benson is a lecturer in Film and Media Studies at Federation University Australia. Her recently completed doctoral thesis unites her interest in film, media, and sexuality studies by examining the complex interplay between marketing texts and representations of bisexuality in contemporary cinema.

Michael DeAngelis, “Introduction,” in Reading the Bromance: Homosocial Relationships in Film and Television, ed. Michael DeAngelis (Detroit: Wayne University Press, 2014), 1.

Heather Brook, “Bros before Ho(mo)s: Hollywood Bromance and the Limits of Heterodoxy,” Men and Masculinities 18.2 (2015): 249.

Peter Forster, “Rad Bromance (or I Love You, Man, but We Won’t Be Humping on Humpday,” in Reading the Bromance: Homosocial Relationships in Film and Television, ed. Michael DeAngelis. (Detroit: Wayne University Press, 2014), 192.

David Halperin, Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 62.

Beth Roberts, “Why Not Bi? The D Train (2015),” Journal of Bisexuality 16.4 (2016): 516, accessed December 21, 2016, doi: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1241091.

Maria San Filippo, The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2013),177.

Lesley Harbidge, “Redefining Screwball and Reappropriating Liminal Spaces: The

Contemporary Bromance and Todd Phillips' The Hangover DVD,” Comedy Studies 3.1 (2012): 10.

For a good overview of this literature see: Cornelia Klecker, “The Other Kind of Film Frames: A Research Report on Paratexts in Film,” Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 31.4 (2015).

Joachim Paech translated and quoted in Klecker, “The Other Kind of Film Frames,” 407.

Abigail Oakley, “Disturbing Hegemonic Discourse: Nonbinary Gender and Sexual Orientation Labelling on Tumblr,” Social Media and Society 2.3 (2016): 1.

“The Hangover 3 Social Media Campaign,” Digital Media Management, accessed January 15, 2015, http://digitalmediamanagement.com/the-hangover-3-social-media-campaign/.

The significance of such ambiguity to bisexual readings has been theorised at length by Maria San Filippo in The B Word (2013), Maria Pramaggiore in “Seeing Double(s)” (2001) and Beth Roberts in Neither Fish Nor Fowl: Imagining Bisexuality in the Cinema (2014).