“I don’t know who I am most of the time”: Constructed Identity in Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

I’m Not There presents a radical departure from the traditional biopic. Rather than focusing on individual agency as a conduit of history, I’m Not There uses the figure of Bob Dylan as a conduit for identity per se. I’m Not There explores the irreducibility of identity by highlighting biopic representation as a textual construct through intertextual allusion, quotation, and pastiche.

Halfway through Todd Haynes’ experimental Bob Dylan biopic, I’m Not There (2007), Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett) reads a character profile of himself in a newspaper. Directly quoting D.A. Pennebaker’s famous Dont Look Back (1967) Savoy Hotel ‘Dylan the man’ sequence, Quinn laughs, ‘God, I’m glad I’m not me!’ in response to the profile’s hyperbolic assertions.[1] Quinn’s incredulous laughter demonstrates that the profile presented to the public is not an accurate reflection of his identity. This moment, however, functions beyond its narrative and character specificity. The utterance speaks to the film’s thwarting of the generic conventions as a biopic, and, through its intertextual reflexivity, to its thematic concern with the irreducible, and ineffable nature of individual existence.

The biopic genre is, as Belén Vidal asserts, often viewed as a retreat into traditional, conservative and formulaic modes of storytelling in which “personality and point of view become the conduit of history in stories that often boil down complex social processes to gestures of individual agency.”[2] While this traditional approach has maintained popularity, some contemporary biopics, such as American Splendor (2003) and Bernie (2011), have revised conventional approaches to subject selection, narrative perspective, and tone. Yet, I’m Not There presents a more radical departure from the traditional biopic than these contemporary entries into the tradition. Rather than focusing on individual agency as a conduit of history, I’m Not There investigates identity itself. By taking Bob Dylan as the film’s subject—a persona both engrained in the contemporary American imaginary and openly acknowledged as a constantly shifting, intertextual and fabricated construct—I’m Not There mobilizes the figure (or more aptly, the ghost) of Bob Dylan as a conduit for identity per se. In the place of storytelling that promises “to reveal the ‘real person’ behind the public persona” in conventional celebrity biopics through narrativization, I’m Not There explores the tensions between the irreducibility of identity, and the impulse to embody the complex and contradictory nature of human existence on film by highlighting biopic representation as a textual construct through its use of intertextual allusion, quotation, and pastiche.[3] Through its interwoven, and deflecting, intertextual references I’m Not There realizes (and, literally quotes) Arthur Rimbaud’s line Je est un autre (“I is another”) through the medium of cinema.

For many, the name “Bob Dylan” is indelibly linked to his 1960s countercultural image as folksinger who rose to acclaim with songs that chronicled social and political unrest in America. Dylan’s cultural importance during this tumultuous time in American history positions him as an attractive subject for a conventional biopic (particularly in what Dennis Bingham terms “the Great Male” variant) as films in this tradition, take as their subject an individual possessing a particular talent, greatness, or vision that sets them apart from the mundane, or “ordinary people.” Indeed, the importance of Dylan and his influence on American popular culture, and national identity, have led to him being labelled “the voice of a generation,” a “prophet.” The celebrity biopic operates on the promise of unfettered or intimate access to “a subject in order to demonstrate, investigate, or question his or her importance in the world; to illuminate the fine points of a personality; and for both artist and spectator to discover what it would be like to be this person, or to be a certain type of person.”[4] Bingham claims that the biopic is bound to represent the subject in relation to the real world—to expose something essential of an individual existence and character through the medium of film. Indeed, the appeal of the biopic genre is the visualization and narrativization of a real person’s private life into a film for public consumption.[5] A life thus must be dramatized in order to be mapped onto the conventions of narrative storytelling. Private acts, moments, and behaviors are ordered into motivations, turning points, and cohesive traits that will be comprehensible to a public audience. In this process the individual is transformed into a character. Therefore, as Bingham points out, the biopic is located in the liminal, space between actuality and fiction. Unlike more conventional biopics, I’m Not There does not attempt to synthesize an individual subject’s attributes into a coherent whole through narrative dramatization. Instead the film presents a “collection of personae” from which the audience is encouraged to dissect identity, myth, and celebrity rather than assemble it.[6] Haynes’ Dylan is portrayed by six fictitious characters—none of which are attributed Dylan’s name— located in disparate geographic spaces, and chronological moments. Bingham claims that the overt fictionalization of Dylan and the focus on his (self-perpetuated) celebrity mythology provides “a sense of greater fidelity to truth” than any attempt to replicate actualities could achieve. As Dylan has employed what Murray Pomerance terms the practice of ‘deeking’ the public to avoid direct access to a single cohesive identity throughout his career, Bingham’s assertion is accurate.[7] However, the overt construction of self as a mechanism for the deferral of access to an authentic, or “real” self can be taken further in Haynes’ work. I’m Not There is certainly a biopic, but by employing Dylan as its subject, it articulates the problem with the representation of identity. I’m Not There is an overt construction, assembled from existing sources from film history and popular culture and thus, it presents identity as entirely textual.

I’m Not There’s presentation of identity as text is both strategic and thematically significant. Biography, portraiture, and biopics, are as Stephen Scobie states, “text, made up of all the formal biographies, newspaper stories, internet statistics, and just plain gossip that has entered into public circulation”—that is, incomplete, imprecise constructions that necessarily integrate actuality with fiction.[8] I’m Not There certainly mobilizes the tension between actuality and fiction inherent in the biopic genre (both thematically and structurally) in part to dramatize and reflect the elusive identity of its biographical subject. However, Haynes’ focus on Bob Dylan provides more than an examination of an infamously elusive celebrity. Bob Dylan presents to the world “a succession of ‘shifting masks’ and ‘moving surfaces,’ or, in his own words, a ‘series of dreams.’ Identity, for Dylan, is always hidden.”[9] ‘Bob Dylan’ is a series of interwoven, created, personas all of which present images of the self at one remove.[10] His recognizability and cultural importance coexist with the fundamental impossibility of pinning him down any singular identity. By instilling Bob Dylan as the subject of his biopic Haynes addresses identity as a fundamentally existential concern, but, in a Dylanesque manner, mediates this sincere underpinning through deflecting and diverging intertextual references.

Scobie conceptualizes Dylan as an embodiment of a dialectic between the “prophet” and mythic figure of the “trickster.” Scobie writes:

There has always been in Dylan’s work a strong element of the prophetic stance: a sternly moralizing view of the world, a keen eye for social injustice and suffering, a demand for America to live up to its Puritan self- conception as “a city on a hill”...This prophetic view was also shaded, right from the beginning, by an apocalyptic sense of living in the end times, initially in the quite literal fear (very real in the 1950s and early 1960s) of nuclear war, and later, in the 1970s and early 1980s in a more traditional religious sense. In more recent times Dylan’s “prophetic” context is to be found not so much in the Bible or in contemporary political events, as in the whole tradition of American popular culture, and in what Greil Marcus calls “the old, weird America.”[11]

While the perception of the Dylan-the-prophet speaks to his place in the American national and cultural identity, his image as an elusive celebrity is far less concrete as it is always connected to his roles as the “trickster.” The trickster, in Scobie’s delineation, can be seen as the flipside of the prophet—both are messengers offering insights on socio-political, cultural, and spiritual issues, but while the prophet promises stability and consistency, the trickster acts precisely to destabilize, and disrupt order. Thus, insights offered by Dylan-the-prophet are sincere, but they are also filtered through an aesthetic wherein “the self which is itself but not quite itself—rather, identity is doubled, divided, or deferred. These images [of Dylan] include alias, mask, mirror, shadow, brother, ghost, and all the echo-effects of allusion and quotation.”[12] I’m Not There mirrors the aesthetic and thematic doubling of the prophet and the trickster. The film encourages the viewer to engage in its intertextual game-play and recognize its references to Bob Dylan yet, this intertextuality acts as constant deferral and thus it serves to simultaneously highlight that he, as the film’s subject, is “not there.” The asymptotic relationship between textual construction and human existence is evident through the film’s title: despite the presence of multiple characters, no clear identity is embodied. The ineffability of human existence is presented as textual identity in which each point of reference and access defers to another site of cultural signification.

Identity Constructed through Intertexuality

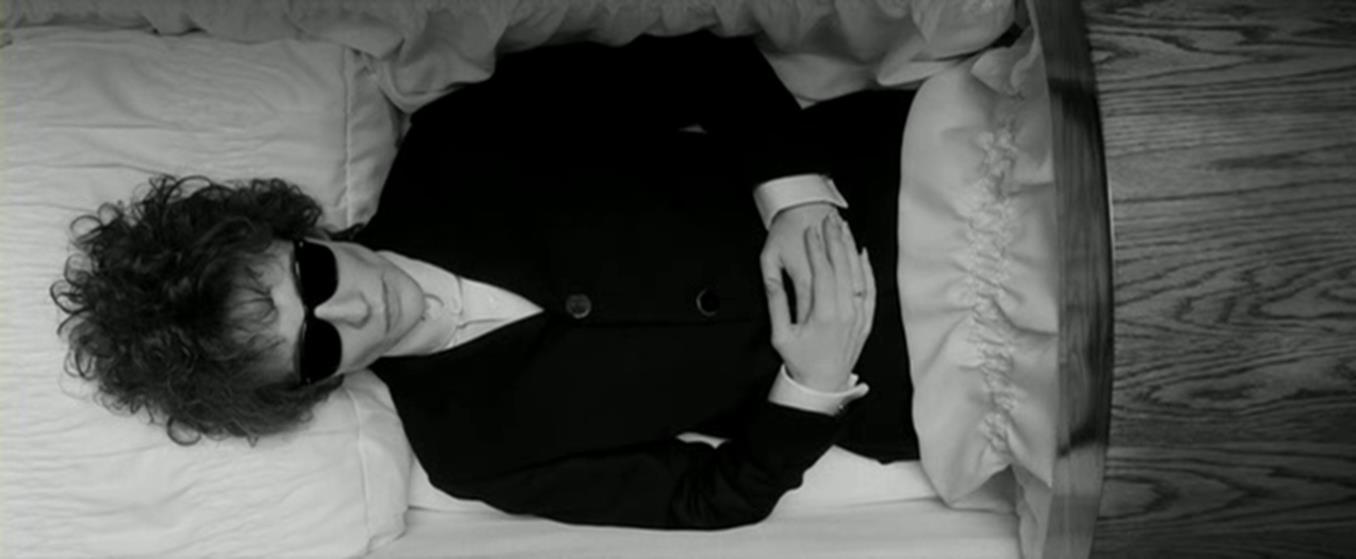

Following the opening title sequence, I’m Not There begins with an aerial shot of an iconic Dylan haircut and hooded eyes. Approximating an amalgamation of the two epitaphs composed by Dylan in his book of poetry, Tarantula, Kris Kristofferson’s voice-over begins “There he lies. God rest his soul...and his rudeness. A devouring public can now share the remains of his sickness, and his phone numbers.”[13] As these humorous, Dylanesque words are spoken, the camera shifts upward to expose the dead body of Cate Blanchett costumed as the electric 1965 Dylan being prepared for examination by two pathologists. As a scalpel cuts into the flesh, the narrator prepares the audience for the autopsy of character. A succession of abrupt cuts (punctuated by non-diegetic gunshots) show the fictional personas who will not only inhabit but create the film’s world. The sequence is narrated by Kristofferson, who introduces the six figures: “There he lay. Poet. Prophet. Outlaw. Fake. Star of Electricity.”

The camera cuts back to the autopsy bed, where the naked corpse has been replaced by an iconic Ray-Ban and suit adorned Blanchett-Dylan in an open funeral casket. The cadaver is immediately recognizable an archetypal image of Dylan and as Blanchett playing that role. In this transition, what began as the promise of an analytical, systematic exhumation of character has been replaced with a pluralized eulogy of multiple sites of subjectivity and myth—reflected in the narrator’s articulation of Tarantula’s epitaph’s final line, that “even the ghost was more than one person.” The idea of recreating or capturing an identity posthumously from the subjective accounts of multiple characters immediately places this film in dialogue with Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941).[14] However, in Citizen Kane the audience arrives together with the investigating journalist, Jerry Thompson, at the final realization that Kane’s identity (like all identities) cannot be fixed or resolutely understood, Haynes, on the other hand, presents a film in which (as the title suggests) this exhumation of character is based on an openly false premise. The audience is informed before the first frame that Dylan (or ‘I’) is not there, and yet for the remainder of the film they are encouraged to seek him out— to piece him together from recognizable sites of contemporary image culture— despite the act’s futility.

James Morrison describes Todd Haynes’ films as:

an art built on pastiche, on the concerted assemblage of reference, allusion, free-form parody and floating signifiers, [his] cinema feeds on the Hollywood tradition as rabidly as it does on a host of other forms and styles—the European art-film, punk, grunge, glam, camp, cult, the cultural underground and the putative mainstream, pop art and pulp fiction—while making a show of casually discarding, or holding in gleeful contempt, the basic premises of the Hollywood model.[15]

As Morrison seems to suggest, I’m Not There is a film “inspired by the music and many lives” of Dylan, however, none of the six characters presented as aspects of the Dylan persona offer the possibility of further engagement beyond the screen as they, and their constructed world, rely on cinema, as a confluence of various cultural streams from the post-WWII era (and image culture) itself.

Each of the film’s six characters illustrate or allude to an aspect of the Bob Dylan myth. Haynes presents both a 19 year-old poet named Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Whishaw) and a young boy named Woody Guthrie (Marcus Carl Franklin) in this film. It is well documented that the poetry and persona of Arthur Rimbaud has been a significant influence on Dylan’s writing, however, this is not that Rimbaud.[16] Rimbaud here is not the French 19th Century poet but a fictional character with the same name who shares enough biographical details to be recognized by the audience as a connection to Dylan (both have retired from writing poetry before the age of twenty, and allude to a capricious and unsettled libertine persona).[17] Yet Haynes’ Rimbaud quotes Bob Dylan lyrics, poetry, and interview responses.[18] Haynes’ Rimbaud signals Dylan’s connection to the poet, however by subverting the necessarily unilateral direction of quotation from Rimbaud to Dylan, a point of origin has been erased and a simulacral figure installed in its place. Rimbaud’s original words are replaced by those they have influenced. Therefore, as an actual biographical figure, that is, as the 19th Century poet, Rimbaud is a contextually and chronologically impossible evocation. Similarly, Haynes’ Woody Guthrie is not the Depression era folksinger that inspired Dylan in his early years as a musician, but rather an eleven-year-old African American boy living in 1959. Haynes’ Woody, like the real Guthrie, plays a guitar painted with the slogan “this machine kills fascists.” However, this Woody also recreates the scene from Arthur Penn’s Alice’s Restaurant (1969) in which Arlo Guthrie visits his dying father, Woody, in hospital (although Haynes does not biologically connect his Woody to the ailing “Mr. Guthrie” in his sequence), and quotes extensively from Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957).[19]

In Woody’s first interaction with some stow-away drifters on a train, he embodies the role of the travelling folk storyteller and explains his experiences:

You got hobos, nobos, gentlemen loafers. One or all-time losers. Call us what you will. Deep down, we're all getting ready to tuck our heads under our wings for sleep. We of the Pullman side-car and the sunburned thumb. We ain’t kidding ourselves. It’s a lonesome roads we shall walk.

This oddly romantic dialogue directly recalls (and references) the personal experience offered by Kazan’s charismatic drifter, Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith) in his interview with radio journalist Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neale):

Whenever a bunch of fellas like us...outcasts, hobos, nobodies, gentlemen loafers... one time or all time losers, call us what you want to... Whenever we get together, we tell funny stories... me and Beanie and the rest of these... hand-to-mouth tumbleweed boys like you see in here. If whisky don’t get us, then women must... and it looks like... I’m never gonna cease... my wandering. But, deep down, when we get ready...to tuck our heads under our wings and go to sleep... we ain’t kidding ourselves.

Woody similarly explains his personal history of growing up in a fictionalized ‘composite’ town called “Riddle” through this exchange:

- Hobo: Uh, is there really a town called Riddle?

- Woody: Tell you the flat truth, that’s sort of a... a whatchamacallit.

- Hobo: A, uh...A composite.

- Woody: A compost heap is more like it by again directly quoting Lonesome’s

by again directly quoting Lonesome’s conversation with Marcia:

- Marcia: Is there really a town called Riddle?

- Lonesome: To tell you the flat truth it’s just sort of a what do you call it...

- Marcia: Composite?

- Lonesome: Compost heap is more like it.

It is not merely that Haynes’ Woody quotes lines from Kazan, but rather that he recites the dialogue from the film in a manner that is almost, but not exactly, identical—as though Woody’s identity is pieced together from imperfect recollections, rather than straight quotations, of past texts. Both Rimbaud and Woody are characters who indicate and mimic Dylan’s influences without embodying them. They are out of time with their namesakes. Arthur Rimbaud quotes Bob Dylan. Woody sings about the boxcar, claims to have learned the blues from a woman called Arvella Gray in Chicago (rather than the male ‘60s street-singer, Blind Arvella Gray), played with Bobby Vee, succumbed to alcoholism during his career as the “Tiny Troubadour” in a carnival that resembles that of Nightmare Alley (1947), and to have found purpose again when he joined the Union cause—events that he, eleven in 1959, could not possibly have experienced. Where these inconsistencies certainly speak to the intertexts and myths created by Dylan’s own fictional, and embellished, biographical accounts, Woody’s approximation of these accounts encourage the audience to recognize that he is a character genealogically constructed from various sites of popular culture and cinema.[20] As John David Rhodes argues, for Haynes “film history is not just an archive of images, but rather an arsenal of aesthetic and epistemological strategies.”[21]

Haynes incorporates the ‘composite’ town of Riddle in I’m Not There as the frontier setting of the film’s “Outlaw” section. In this section Billy the Kid (played by Richard Gere) returns home to find that he is almost unknown to the townsfolk, who are costumed for a Halloween festival (as the narration states, “No town ever loved Halloween quite as much as the town of Riddle, so who a fella really was never really mattered”). The Halloween setting recalls a statement made by Dylan during a New York concert on October 31, 1964 “It’s Halloween, I have my Bob Dylan mask on. I’m mask-erading.”[22] The evocation of this factual event, and its playful deferral and doubling of identity, is paralleled in I’m Not There as the town costumed citizens greet Billy by various names. A man dressed as a lobby boy calls Billy ‘Mr. Gladstone’, the pseudonym Benjamin Braddock assumes in his Taft Hotel rendezvous with Mrs. Robinson in Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967), while a young boy dressed as Charlie Chaplin’s tramp (played, like Woody, by Marcus Carl Franklin) begs Billy to help him escape, as “this here is chickentown.” “Chickentown” here refers to frustrating and repetitious dystopia created by John Cooper Clarke in his performance poem, “Evidently Chickentown.”

Using the same palette as Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), this section recalls revisionist westerns, in particular Dylan’s role as the appositely named “Alias” (and soundtrack composer) in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). Haynes complicates this reference to Peckinpah through the maturation of “the Kid” character. I’m Not There’s narrator, Kris Kristofferson, played “the Kid” in Peckinpah’s film at the age of 36 whereas Gere’s Billy is shown as a weary, bespectacled man, plagued by visions of war, approaching his sixties. In a manner not dissimilar to Altman’s appropriation of the Korean War as an allegory for America’s involvement in Vietnam in M*A*S*H (1970), it is not, as the historical context of the Western genre would suggest, memories of the Civil War that torment Billy. Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid deconstructed the Western to present

a country full of men without a future, whose way of life is being replaced by the evil forces of eastern business interests...[a Western] about people just waiting around to die...[where violence] is shown to be a pointless, inconclusive (with the notable exception of the Kid’s death), comparatively unspectacular act carried out almost from a force of habit.[23]

In contrast, Haynes’ “Outlaw” section reconstructs the Western setting, with visions of the Vietnam War literally infiltrating the film frame. Billy’s scenic view of tree-covered hills on his approach to Riddle is overlayed with memories of war through the gradual introduction of sonic disruptions before cutting between televised war footage, the serene vista, Billy’s thousand-yard stare, and shifting spatio-temporal planes to show Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), watching the televised war from her bedroom as her marriage breaks down, before returning to Billy.

Haynes presents “Riddle” not only as the composite Western town seen in Altman’s and Peckinpah’s revisionist image of the genre, but as an assembled film set from which giraffes emerge from barns behind the power-lines as Calexico and Jim James perform Dylan’s “Goin’ to Acapulco” in front of the open casket of a young suicided woman whose appearance recalls John Everett Millais’ Ophelia. Jim James’ appearance in this emotive sequence in commedia dell’arte whiteface further emphasizes the deference and doubling of points of reference. The painted mask functions as an allusion to the Italian theatre tradition, the evocation of that tradition by Dylan on his “Rolling Thunder” tour, and the incorporation of those performances in his experimental film Renaldo & Clara (1978) as a film that, like Dylan’s persona and Haynes’ film, centers on “masks, disguises, assumed names, and shifting identities.”[24] Riddle is a composite, anachronistic set upon which the mythology of national conflicts collide and intermingle—the frontier, metacinematic evocations of the Western, the Vietnam War, and the mass dispossession of family homes through the self-interested power of eminent domain by government officials. This form of anachronism corresponds to Elena Gorfinkel’s formulation in which “there is both a historicist and fabulist strain in the creative marshalling” of the film world’s construction “which hinges on sly misuses and creative revisions of historical and film historical referents.”[25] Gorfinkel writes of the historical definition of anachronism that:

within a contemporary vernacular and in its commonplace meaning, to mark something, a cultural object or figure, as anachronistic is to suggest that it is out of place, misplaced from another time. It is often seen as a slight—anachronism is after all understood as a type of mistake in the practice of historical representation.[26]

However, this criticism only holds up if one assumes that the intent of a text is to represent history. It is important that these anachronistic elements are not taken to be naïve in Thomas Greene’s sense (“in which the anachronist takes on a relation to ‘proper’ history, a relationship which must either be excused, justified or condemned”).[27] The merging of diffuse historical, contemporary, and futuristic contexts promotes identification, nostalgia and projections that are unable to be specifically placed in a chronological context that is wholly contemporary, retrospective or speculative.

Rather than presenting a dynamic, plot-driven Western, Maximillian Le Cain provocatively writes that Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

is practically plotless. Instead, Peckinpah presents us with a loose series of poetic vignettes pointing towards the moment when Garrett shoots the Kid and then his own reflection in a mirror. Rather than leading up to this action, the film seems simply to wait for it.[28]

Haynes’ film may appear as a series of interwoven vignettes, however, rather than these moments culminating in a violent act of destruction they simply reflect the film’s original existential crisis—the identity being investigated does not add up to an understanding of place and self through anachronistic references, but a myriad of deferrals and blockades. Haynes not only resists naturalism, but as Rob White writes, his film is “a tapestry woven from the threads of other films—strands of dialogue, character, mise-en-scène...[its] environment is a patchwork world, with no true identity.”[29] Pat Garrett (Bruce Greenwood) here is no longer a (problematic) lawman out to betray an old friend, rather the man who has sold the town of Riddle (and with it, the composite site of American mythology) to make way for a five-lane interstate highway. Pat Garrett does not need to shoot Billy (or his own reflection) at the section’s conclusion, as he and much of Riddle have forgotten that Billy exists.[30] Through this, Haynes portrays these American myths and their incarnations during the tumultuous 1960s, with which the image of countercultural “Bob Dylan” is intricately bound, as slipping into an achronological and porous retirement—as images and instances that are removed from original contexts and placed in overlapping cinematic recyclability.

I’m Not There does not present six separate stories with distinct spatio-temporal logics, but one layered, cross-spatio-temporal, achronological film world based on an assemblage of references within popular culture and film history. The stories and characters bleed into, and overlap with, one another. Haynes allows film allusions to cross the narrative’s six sections; Dylan’s song lyrics are repeated as dialogue, and actors reappear in new locations in different roles. Bruce Greenwood plays both Pat Garrett and Time Magazine reporter Keenan Jones in the Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett) section of the film. Keenan, here, is the “Mr. Jones” of Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man”, a figure whose continual inquiry into that which he cannot understand leads only to more befuddlement. Although I’m Not There provides the illusion of focusing on the labyrinthine persona of Dylan as a musical figure, “Ballad of a Thin Man” is the only song presented in the style of a music video. The song is played while the visuals cut between Quinn performing, and a series of illogical, impressionistic and bizarre images focusing on Keenan. Haynes complicates this moment by mirroring the lyrics (You hand in your ticket / And you go watch the geek / Who immediately walks up to you / When he hears you speak / And says, “How does it feel / To be such a freak?”/ And you say, “Impossible”/ As he hands you a bone / Because something is happening here / But you don't know what it is / Do you / Mister Jones) in visual allusions to the 1947 film Nightmare Alley, which documents the fall of a successful conman to a drunkard, who by the film’s conclusion is only able to play a carnival geek.

The representation of Cate Blanchett as Jude Quinn is immediately recognizable as the enigmatic electric Dylan—yet the casting of Blanchett (as a highly acclaimed, and female, performer) in the role functions to reiterate the constructed nature of the biopic as a genre that necessarily incorporates artificiality in order to present portraits of individual lives. Much of this section is appropriated from D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary Dont Look Back, and as such Keenan Jones is recognizable as an inverted fictionalization of Time Magazine reporter Horace Freeland Judson, at whom Dylan levels a (perhaps) contrived tirade of abuse on the nature of knowledge, obligation, and media representation. Although Pennebaker’s direct cinema style provides the illusion of unfettered access to the “star” of Dylan, many criticisms have been levelled at the film around the issue of self-performance perpetuating the Dylan myth.[31] In directly quoting scenes and appropriating dialogue from Pennebaker’s film within an openly fictionalized construct, Haynes problematizes the notion of unfettered access to identity through layers of performance and allusion.[32] The biopic, like the ‘behind the scenes’ Rockumentary, is centered on a yearning to access the “truth” of a person—thus, by quoting Dylan’s performance in Pennebaker’s film Quinn functions as a mediation and a displacing mechanism. Quinn is at once comforting as he is the most familiar image of Dylan depicted in the film, and yet he is source for existential unease. He is a simulacrum—an overt performance of a popular culture image that had been performed for Pennebaker’s “access all areas” Rockumentary. The use of high-contrast black and white in this section also recalls Federico Fellini’s poetic realism. The fluidity between dream and reality in 8½ (1963) is reflected in a moment where, like Guido, Quinn is shot floating in the sky as a human balloon.[33] The suffocating sense of individual alienation Fellini presents in Guido’s driving-dream sequence is similarly evoked as a distraught Quinn has his blood pressure taken in a limousine, while the sound of his heartbeat overpowers the soundtrack.[34] The sense of alienation and existential anxiety present throughout I’m Not There is reflected in a sequence in which Quinn attends a Warholesque party.[35] Alone and anesthetized by barbiturates, Quinn collapses as a large tarantula is projected onto the walls around him. In biographical terms, this references Dylan’s prose poetry collection Tarantula, however Haynes’ slippery cinematic construction pluralizes this allusion as a thematic effect. The image of a tarantula equally quotes Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966)—a film concerned with identity where, again, reality and dream states are blurred beyond recognition, and televised images of global atrocities like the Holocaust and Vietnam War haunt the characters.

As dream states and reality blur in both Fellini’s and Bergman’s work, cinematic allusion and biography here meld to fix identity within film and image cultural history in response to the impossibility of capturing any true human essence. The indexical nature of experience lived through the film image is most evident in Robbie (Heath Ledger) and Claire’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg) section.

Robbie is an actor who has risen to fame for a role in the film A Grain of Sand, a biopic of Jack Rollins (the title character of the section played by Christian Bale).[36] Where the Jack Rollins section within I’m Not There is presented as an expository documentary (in contrast to Pennebaker’s approach), quoting significantly from Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home (2005), A Grain of Sand positions Haynes’ film in contrast to audience expectations of a more conventional biopic.[37] In this section, the presenter promises to bring her audience face to face with the real “Jack Rollins.” This, of course, can never occur.

The collapse of Robbie and Claire’s marriage presents the most conventional narrative of the film, incorporating a falling-in-love montage that begins with the couple recreating the intimacy and excitement scene between Dylan and Suze Rotolo on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan”, and a “dear John” divorce letter sequence. The sequence begins with the narration:

That’s when she knew it was over for good. The longest running war in television history. The war that hung like a shadow over the same nine years as her marriage. So why was it suddenly so hard to breathe?

Robbie and Claire meet in a Greenwich Village café in the 1960s. During this meeting Robbie learns that Claire is a French artist, to which he exclaims “that’s perfect!” This utterance, rather than merely signaling the commencement of a conventional boy-meets-girl storyline, alludes to the section’s homage to Jean-Luc Godard. Haynes visually alludes to Le Mépris (Contempt) (1963), 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle (2 or 3 Things I Know About Her) (1967), La Chinoise (1967), with scenes and dialogue directly quoted from Masculin Féminin (1966). In their first encounter Claire quotes Godard’s Madeleine (from Masculin Féminin) by asking Robbie “what is at the centre of your world?” To which Robbie responds by offering an approximation of Madeleine’s answer (“Me”). He responds with “Well, I’m 22. I guess I would say, me.” The construction of Claire and Robbie’s relationship is thus not based on the ideal of two characters genuinely falling in love after their first meeting, as occurs throughout the romance genre (Titanic [1997], Say Anything... [1989], The Notebook [2004]), but is rather based on, and born out of, a generic romantic entanglement as presented by cinema as a historical, and cultural, imaginary. Haynes reinforces this position through the incorporation of Godard-esque intertitles accompanied by the sound of gunshots, which, in contrast to the most mainstream interpersonal narrative of the film, disrupts the plot in a form that approaches a Brechtian distanciation.

Masculin Féminin is again quoted in the premiere of Grain of Sand. The narrator explains Claire’s disappointment in the film and ultimately in their failed vision of the future, stating:

The more they tried to make it youthful, the more the images on the screen seemed out of date. It wasn’t the film they had dreamed, the film they had imagined and discussed. The film they each wanted to live.

Taken alone, this sentiment could be said to speak for the inability of direct address to convey the existential anxiety of our contemporary society; however, in deriving this profound statement from Godard, Haynes creates a double play in his use of the utterance. Not only does the statement directly convey the difficulty of expressing existential anxiety in contemporary cinema, but in the context of I’m Not There, a film fundamentally concerned with recreating and understanding identity (not just of the counter-cultural figure Bob Dylan, but identity per se) Haynes’ statement of sincerity is appropriated from another film source—the anxieties are sincere, but like the acts of the “trickster,” they are not representable in any direct manner. The film’s final moments end with a series of these recognitions—Claire’s section acknowledges the limitations of cinema, Quinn’s section demonstrates the construction of character, and Billy formally addresses the film’s anachronistic structure. Following a rant about the rejection of his new electric recordings, Quinn matter-of-factly states “Everybody knows I’m not a folk singer,” before turning to smile at the camera. White states that this is a moment in which Quinn acts “serenely, smugly, with a camera-loves-me complacency that takes the audience’s approval for granted,” however, given Haynes’ deliberate focus on identity and construction, this moment is more accurately read as the reinstatement of Cate Blanchett within the film. Here, the gradual smile is knowing.[38] Without the Ray-Ban sunglasses, and relaxing the hardened and exhausted expression held throughout the film, the audience is forced to recognize Blanchett as an actor who has inhabited a role. In this final moment Blanchett explicitly positions herself as “a body too much” in Jean-Louis Comolli’s conception, and removes the electric-Dylan mask she had adopted. The overtly recognizable Dylan of the Quinn section is, in this reflexive smile, over.

Haynes explicitly articulates the shifting and multidirectional nature of identity that he has created in I’m Not There with Kristofferson’s final lines:

I can change during the course of a day. I wake and I’m one person and when I go to sleep I know for certain I’m somebody else. I don’t know who I am most of the time. It’s like you’ve got yesterday, today, and tomorrow all in the same room. There’s no telling what can happen.

Conclusion

Conventional biopics, as narrative films, facilitate a relationship with the spectator based on identification that privileges a set of emotional responses. Carl Plantinga writes that in mainstream narratives, there is a “consistent ebb and flow of emotion, rooted in clear and relatively simple paradigm scenarios, and kept simply and on course in...a linear narrative.”[39] As characters are often presented as agents of causality within a film, their traits are often individualized and consistent so that they can be used as narrative functions or a means of negotiating a film’s milieu.[40] By contrast, I’m Not There does not focus on conventional narrative elements of identity formulation in a generic sense; instead, Haynes’ film uses postmodernist techniques such as allusion, pastiche, and quotation to present identity and selfhood as an unknowable entity through fragmented, disparate, and layered representations of a popcultural myth of celebrity. I’m Not There does not provide access to any characters in a manner that facilitates audience identification and character alignment, as there is no linear narrative in which these characters can be situated. Where mainstream cinema “aspires to verisimilitude by making the audience feel they are part of the action and encouraging identification with the characters in the film,” Haynes’ work subverts the conventional relationship between spectator and film predicated on the psychological process of identification.[41] I’m Not There presents only the illusion that the spectator may come to understand its characters as part of the Dylan persona. The film encourages spectators to recognize its imagery from popular culture and celebrity mythology, and to associate it with real-world referents as though they offer the personal insights promised by the biopic genre. However, I’m Not There’s is, like the Dylan-inspired characters that inhabit it, at once familiar to the audience and an overtly inaccurate representation of historical reality. Here the real-world referents of more conventional cinema are replaced with something more simulacral.

The film’s focus on the construction of identity and myth in lieu of “truthful” interpersonal intimacy promised by the biopic genre complemented by the film’s aesthetic and structural strategy in which found, and often disparate, objects are placed in relation to each other as an overt assemblage that is atemporal, achronological, and porous. The porosity of this overt construction provides a site for the examination of human identity that is always incomplete. I’m Not There subverts generic conventions in that it does not re-create the life of Bob Dylan as an agent to be read in relation to history, or provide access to something essential of his identity, but instead provides series of intersecting texts that splinter off in diverging directions. The unapologetic self-conscious construction of I’m Not There responds to the generic imperatives of the biopic by presenting its subject as a textual identity an entity that is always displaced. Thus, at its core I’m Not There is primarily concerned with existential unease—but presented by the “trickster”— and therefore always shifting, and kept at a distance.

Author Biography

Kim Wilkins completed her doctorate at the University of Sydney. She has published work on existential anxiety in contemporary American cinema in the New Review of Film and Television, and in a collection on Wes Anderson through Palgrave Macmillan.

Notes

In Don't Look Back, Dylan is filmed reading a news article that reports “Bob smokes 80 cigarettes a day,” to which he responds “I’m glad I’m not me!”

Belén Vidal, “Introduction: the biopic and its critical contexts” in The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture, eds. Brown and Vidal (London and New York:Taylor & Francis, 2014), 3.

Dennis Bingham, Whose Lives Are They Anyway?: The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genre (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010), 5.

George F. Custen writes that as film is a mass object for cultural consumption the configuration of a life into the cinematic form plays a significant role in the shaping of public history. “Configuring a Life.” Chap 5 In Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public History (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 117-213.

“Deeking” is a term used in Canadian ice-hockey slang whereby a player fools his or her opponent by looking in one direction before moving in another in an attempt gain control of the puck. Pomerance used this term to describe the self-aware manner in which Jesse Eisenberg conducts himself in interviews in order to evade questions in a workshop panel, titled “American Smart Film” presented at the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Conference, Chicago, March, 6-10, 2013.

Stephen Scobie, Alias: Bob Dylan Revisited (University of Michigan: Red Deer Press, 2004), 85.

Marcia Landy also draws a comparison between Citizen Kane and Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine (1998). Landy comments on the latter film’s structure as an investigation into the rise and fall of an individual, Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), investigated by a reporter (played by Christian Bale)—where through the multiple perspectives of various characters and the investigator’s own participation in the glam scene—it eventuates that no version of Slade can ever be considered definitive. "Storytelling and Information in Todd Haynes' Films." Chap. 1 In The Cinema of Todd Haynes: All That Heaven Allows, ed. Morrison. (London: Wallflower, 2007), 19.

James Morrison, "Introduction." In The Cinema of Todd Haynes: All That Heaven Allows, ed. Morrison (London: Wallflower, 2007), 2.

Todd Haynes, like Dylan, shares a fascination with the poet Rimbaud. While finishing his undergraduate degree at Brown University, Haynes made Assassins: A Film Concerning Rimbaud (1985). Like I’m Not There’s Dylan(s), Assassins, writes Joan Hawkins “is less about Arthur Rimbaud the real boy-pet than it is about “Rimbaud,” a character we have largely constructed from his writings and from the legends and myths that have grown up around him.” "Now Is the Time of the Assassins." Chap. 2 In The Cinema of Todd Haynes: All That Heaven Allows, ed. Morrison (London: Wallflower, 2007), 25.

Haynes explicitly links the young Woody Guthrie to his real-life namesake in the conversation held between Woody and the two other stowaway hobos on the railroad train, in which one man notes that his name is “just like the singer”—however, Haynes’ Woody does not respond to this observation in any way.

As well as Hunter S. Thompson’s “Seven simple rules for a life in hiding” from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Dylan did visit Woody in Greystone Hospital in the late 1950s, however, within the context of Haynes’ film, this simultaneously alludes to history, while positioning itself in relation to the representation of these histories on-film.

Early in the film a woman who has taken Woody in for a meal exclaims, “Tell you what I think. I think it’s 1959 and this boy’s singing songs about the boxcar? Hmm. What a boxcar gonna mean to him? Right here, we got race riots, folks with no food. Why ain’t he out there singing about that?”

Blind Arvella Gray was a male blues and folk musician from Texas.

Landy writes (comparing Haynes’ narratives to Walter Benjamin’s concept of storytelling and information) that “through forms of theatricality—not conventional realism—Haynes’ films exceed stable and conventional forms of representation, mindful as they are of the role that media have played in the transformation of knowledge.” "Storytelling and Information in Todd Haynes' Films", 9.

John David Rhodes makes a similar point in relation to Haynes’ Safe (1995), stating “Very often when we look at an image or shot from Haynes’ film...we are also looking (or being asked to look) through them: either to shots from other films by other directors, or else to other fields of reference.” "Allegory, Mise-En-Scene, Aids: Interpreting Safe." Chap. 6 In The Cinema of Todd Haynes: All That Heaven Allows, ed.. Morrison. (London: Wallflower, 2007), 68.

Maximilian Le Cain. "Drifting out of the Territory: Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid." In Senses of Cinema. '70s US Cinema: Senses of Cinema, 2001.

Elena Gorfinkel, "The Future of Anachronism: Todd Haynes and the Magnificient Andersons." Chap. Three: Techniques of Cinephilia: Bootlegging and Sampling In Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, eds. de Valck and Hagener. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005), 156.

Ibid.

Gorfinkel describes filmmakers that “utilize allusion, but also eclipse it, in their preference for a kind of overt aesthetic and temporal disjunction, creating an intended rift between the constitutive aspects of their filmic worlds. The viewer always inevitably becomes aware of his or her own position, caught between different periods, in a region of illegible temporality and mobile film historical space.” 155.

Rob White, Todd Haynes: Contemporary Film Directors. ed. ames Naremore (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 2.

White here is describing Haynes’ Far From Heaven, however, the statement is equally true of I’m Not There.

A newspaper man is shown pedaling an edition with the headline “Now You See it Now You Don’t: The Rise and Fall of Township Riddle” and calling “buy it here, read it there! An epic tale of blunder and despair! A withering saga of mystery unveiled, a swansong to America before Chaplin sets sail or the children of dawn in crazy duress ever watched the red sun without bothering to dress!”

The recreation and distanciation of the Dylan myth has more recently been employed by the Coen brothers in their film Inside Llewyn Davis (2013). Interestingly, the Coen brothers do not use a Dylan figure as the protagonist of their film, but the Dylan myth lingers in a complicated, and not entirely celebratory, manner as a shadow to their narrative.

The notion of celebrity and star power on screen is further complicated in Haynes’ film in a sequence in which Quinn emerges (from a literal puff of smoke) with The Beatles, and together they roll about on the lawn in intoxicated states. During Quinn’s interview with Keenan Jones The Beatles are shown in the background running from a crowd of crazed fans in fast-motion, referencing the opening sequence of A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

Haynes further quotes 8½ in a sequence following Jude Quinn’s first performance of “Maggie’s Farm” using electric guitars and a band, Haynes shows a series of (mostly) disgruntled audience members talking to the camera about their feelings of betrayal. These figures are then shot arranged in a single line, facing the camera.

In addition to these instances, music from Il Casanova di Federico Fellini (Fellini’s Casanova) 1976) is played during an exchange between Coco and Quinn. The dialogue of this sequence borrows lines from Dylan’s “She’s Your Lover Now”.

The character Coco Rivington (Michelle Williams) is an assemblage of the Warhol world, and, more directly Edie Sedgwick.

This title is taken from Dylan’s 1981 release Every Grain of Sand.

I use Bill Nichols’ terms here in order to differentiate between the two types of documentary quoted by Haynes. Nichols identifies six documentary modes in his book Introduction to Documentary (Second Edition), (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2010)—the poetic, expository, observational, reflexive, and performative. Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back can be described in these terms as an observational, or fly-on-the-wall style of documentary (although the nature of Dylan’s performance does prove problematic in this demarcation) whereas Scorsese’s No Direction Home can be categorized as expository due to its use of voice-over narration, interviews, and found footage.

Carl Plantinga, Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator's Experience (Berkeley: University California Press, 2009), 93.

Paradigm scenarios are “types and sequences of events that are associated with certain emotions” ibid: 80.

David Bordwell, "Story Causality and Motivation." In The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960, eds Bordwell, Staiger andThompson, (London: Routledge, 1985), 14.

Jill Nelmes, "Realism and Screenplay Dialogue." In Analysing the Screenplay, ed. Nelmes, (London: Routledge, 2010), 217.