“Goodnight Mommy: Radical Loss and Desperate Measures”

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

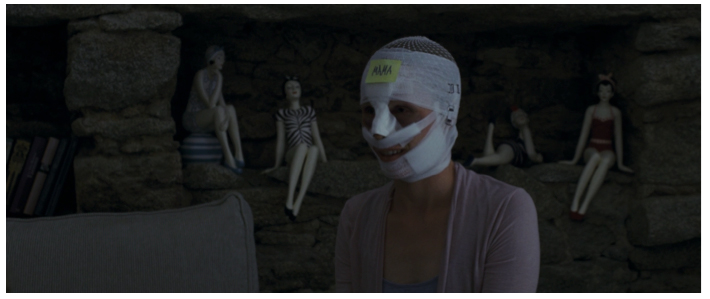

Ich seh ich seh (trans. Goodnight Mommy, Austria, Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz, 2015) is a film about righting a radical wrong. Elias and Lukas (Elias and Lukas Schwarz), identical twins, begin to suspect that their mother (Susanne Wuest), who has returned home after having cosmetic surgery, her face largely obscured by gauze bandaging, is not really their mother. This suspicion is compounded by her inexplicable coldness toward Lukas, by her anger with Elias, and by her demand for quiet so she can recover. As her strange behavior persists, the twins become more thoroughly convinced that this woman is an imposter, and the plot is driven by their desire to restore the order of the past.

It is impossible to discuss the film without acknowledging a certain factor that, in a less substantial film, would be exposed in a “Big Reveal” moment—a moment that we are thankfully spared. That only Elias can see Lukas—that he is, in fact, dead—is evident early in the film and gradually confirmed as the narrative progresses. Such a “twist” is not the point at all. The question is how Elias deals with this traumatic loss, a question which is hinted at toward the beginning of the movie as Lukas disappears into the darkness of a cave; Elias calls out to him, waits, then hesitantly follows.

Lukas serves as a literal representation of Elias’s ideal-ego, a point of reference for emulation, which is made manifest in the shot right before the title appears on screen, concluding a montage of play. Elias floats on a raft in the middle of a dark lake, hovering above his own reflection; it is implied that Lukas has gone under the surface and will flash up in an effort to scare him. Elias calls his name, but there is no answer—only bubbles coming up from beneath, headed toward him. The rest of the movie is concerned with Elias’s efforts to cling to those bubbles, the vestige of Lukas (the identity constructed in relation to him; the reality constructed around him), and his determination to displace the loss somewhere else.

The opportunity for this displacement, this shift, appears most obviously in the form of a game early in the film, wherein Elias dons a sticky-note on his forehead with a word written on it; he must ask questions to his mother (the Other) in order to learn who or what he is (according to the sticky-note). The next round is the mOther’s turn. Elias christens her “Mama” with the sticky-note; the clues he gives in response to her questions leave her stumped until he hints to her that she, as “Mama,” has two children. The mOther becomes somber, at a loss for words; this description of “Mama,” the signifier with which she has long identified, is no longer appropriate.

The film, suggestively from Elias’s perspective, shows how Mama becomes a radical impossibility, her stable identity interrupted by loss. This impossibility is literalized in two works of art that hang prominently in the house, each of a blurred female figure. Mama herself acquires this blurred, non-recognition when, in a fantasy sequence, she walks into the woods, strips off her clothing, and, as the camera moves to reveal her face, her head begins to rapidly shake, leaving her face an indistinct blur. Mama as object exceeds representation. The bandages covering her face signify this otherness, an externalization of the essential change that Elias perceives in her.

Elias is a sullen descriptivist: for him, the content of “Mama” does not change; so if this self-proclaimed “Mama” rejects that content (by ignoring Lukas and begging Elias to do the same) she must not be that which “Mama” designates but some radical point of break from reality. “Mama” becomes the symptom, the inconsistency in his framework of reality. Rather than accept the death of Lukas, he interrogates this symptom, trying desperately to mend the fissure.

What follows is both desperate and brutal. Elias is driven by Lukas (in an effort of self-preservation on the latter’s part) to do terrible things to the imposter-Mama in order to restore the consistency of reality, to get back the Mama of both Elias and Lukas, which is impossible. In one scene, the mother wakes up with her eyes glued shut; one of her eyes successfully opens, thus symbolizing Elias’s perceived problem—that she sees only one of them. (This significance is somewhat lost by the decision not to directly translate the original German-language title as “I see, I see.”) When these efforts prove useless, he takes the final, inevitable step to resolve the tension, the unbearable discord.

Ich seh ich seh is a film that can easily be overlooked by general audiences. Its object of fear is not something to be found under the bed or in the shadows; rather, it is the inescapable, definitive lack in our framework of reality and the lengths to which we will go in order to avoid confronting it. Elias’s actions, spurred on by the visceral memory of Lukas, are gruesome and terrible to watch. But the ending of the film could readily be interpreted as a happy one: the framework of reality closed once more, the tension resolved: a totality purified by fire.

Author Biography

Dabney Tyler Waring is a writer in Tallahassee, Florida; he holds a B.S. in International Affairs and a B.A. in Chinese Language and Culture from Florida State University. He is interested in critical theory, political philosophy, and literature. And, of course, films.