Navigating Space and Racial Microaggressions as an Undocumented Latinx Millennial

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

Racial microaggressions have increasingly become a topic of interest among scholars. Racial microaggressions are what Sue and colleagues (2007) call the “commonplace verbal or behavioral indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults” (p. 278). Most of the research in this area focuses on counseling psychology (Sue et al., 2007) and how college students experience racial microaggressions on campus (Yosso, Smith, Ceja, & Solórzano, 2009; Minikel-Lacocque, 2013; Nadal, Wong, Griffin, Davidoff, & Sriken, 2014; Ballinas, 2017; Keels, Durkee, & Hope, 2017). We know from the research that racial microaggressions directed at Latinx students often entail ideas about Latinxs as foreign and intellectually inferior (Yosso et al., 2009; Ballinas, 2017). How can we make sense of racial microaggressions directed at Latinxs that occur outside of universities and classrooms?

My work on racial microaggressions emerged from asking Latinx millennials two open-ended questions: Where do you feel you belong? and Where do you feel you least belong? I asked these questions in 2015 to 2016 as part of a larger project on how members of mixed-status families experience belonging and negotiate illegality in their lives. These mixed-status families included members who are U.S. citizens as well as undocumented immigrants with and without the Deferred Actions for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) provisions. Undocumented refers to immigrants without legal authorization to preside in the United States; DACA temporarily allows some undocumented youth access to a work permit, protection from deportation, and other benefits. My two interview questions could have been met with answers about immigration, but instead they mostly inspired young Latinxs to think about the racial politics of space in their communities in Los Angeles County.

Although I interviewed 34 U.S. citizen Latinxs and other members of mixed-status families, here I highlight the experiences of 8 college-going and college-educated undocumented young adults ages 18 to 28. For the most part, young adults were no longer navigating the county of Los Angeles with immigration status in mind. For some, DACA protections provided peace of mind, and California Assembly Bill 60 allows driver’s licenses to immigrants regardless of immigration status. Los Angeles is also a sanctuary city, meaning that local law enforcement does not work with immigration agents to identify, detain, or deport people without legal status. Given this somewhat immigrant-friendly context, young people were not constantly living with the fear of deportation. This does not mean fear entirely leaves the equation, it just means immigrant youth did not have to make the everyday mental calculation about immigration status when moving through Los Angeles.

Results

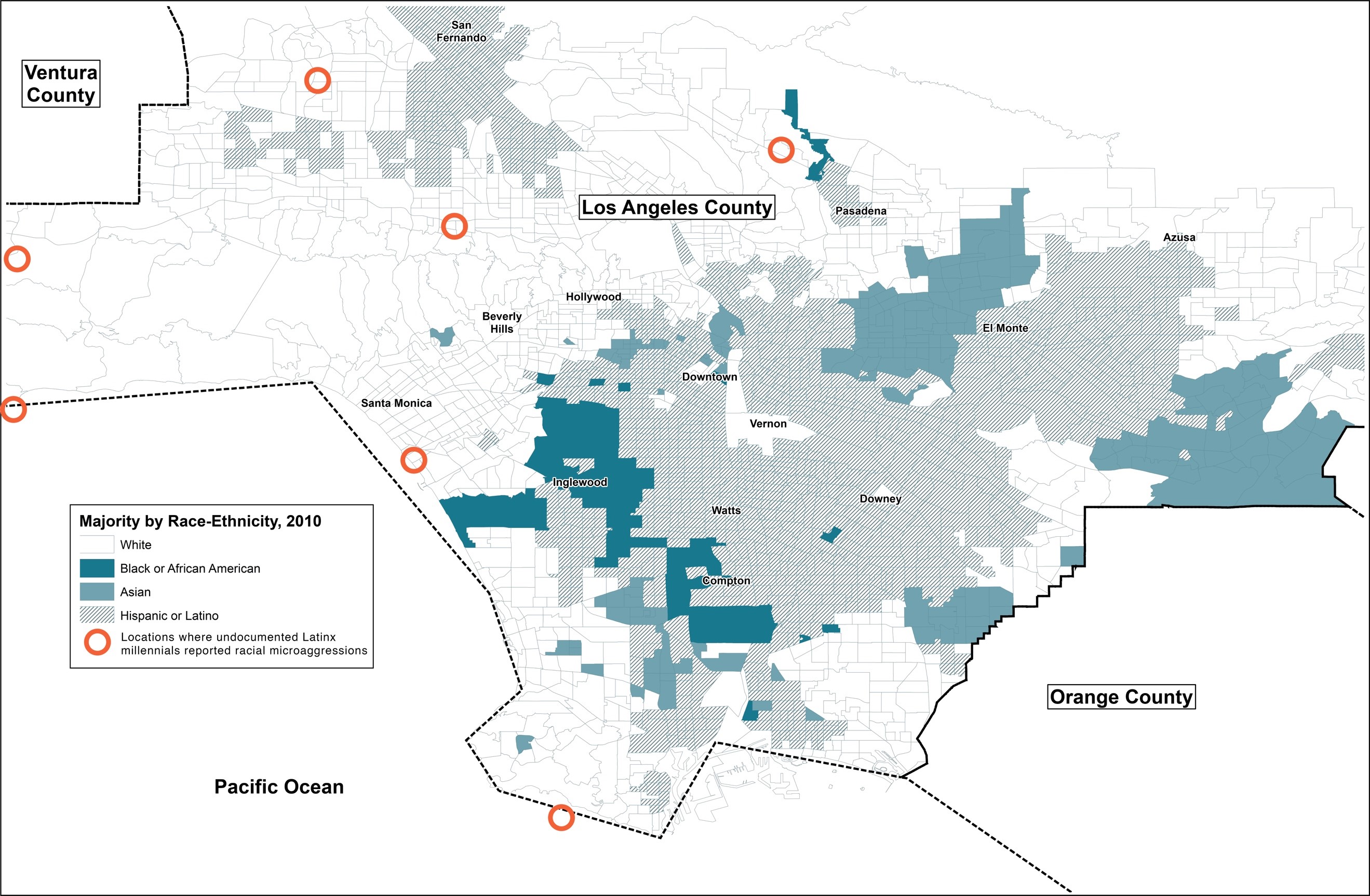

Many undocumented Latinx millennials in my study had come of age in largely Latinx, immigrant-friendly, homogenous communities. It is in these neighborhoods that young adults reported that they rarely felt like racial or immigrant outsiders. I came to learn that young adults saw predominantly White neighborhoods and public spaces as places where they do not belong, and they felt this way based on their experiences of racial microaggressions in these spaces. Undocumented Latinx millennials experienced racial microaggressions spatially as they moved through Los Angeles and found themselves in predominantly White neighborhoods and public settings, such as restaurants, malls, and retail stores (see Figure 1).

The racial microaggressions in predominantly White neighborhoods ranged from the subtle to the overt. Research participants discussed with me the insidious stares that White strangers directed at them, stares that suggested, why are you here? And worse, you do not belong here. These microaggressions occurred as young adults carried out everyday activities and participated in activities of leisure. One participant, Matthew, for instance, found himself experiencing a racial microaggression at a beachside restaurant while celebrating a one-year anniversary with his girlfriend. As the only Latinx patrons and one of two couples of color present at the busy restaurant, Matthew and his partner felt hostile stares and sneers in this mostly White space.

At times, racial microaggressions were more explicit. In these cases, young adults were told different variations of “go back to Mexico” or “go back to your country.” For undocumented Latinx millennials, these racial microaggressions are particularly unsettling even when Los Angeles provides an immigrant-friendly policy context. These comments were made without knowledge of young people’s immigration status or ethnicity. The verbal assaults were an explicit reminder that these young people were considered unwanted outsiders. It also demonstrates how microaggressions directed at Latinxs implicate a conflation between race and immigration status.

Latinx millennials also recalled racial microaggressions from childhood that were directed at them and their families. A participant in the study, Cecilia, for example, reflects on how 1990s-era public discourse surrounding immigration and welfare reform shaped the microaggressions she and her family faced growing up:

That whole media coverage from the early 90s kind of stuck with some people. You know, that whole typical headline of immigrants taking over and the mom and the dad with all the little kids, the image of the family with the ten little brown kids. I feel like when they see us they kind of think that. ... We would go somewhere and it would be me, my sister, and my brother. It was just the three of us but people would look at us like: here comes the lady with the three kids.

Cecilia remembers racist incidents and microaggressions that did not occur in Latinx neighborhoods. Instead, these microaggressions would happen in cities that were predominantly White.

For some millennials, experiences of racial microaggressions in White spaces means avoiding majority-White locales. For others, such experiences sting but do not change where they travel within the city or county. As Xavier, another participant, put it, “I know what I can do and can’t do in this country. I know the rules and the laws so if there is a racist place where they hate Hispanics or something...I would just go in because they can’t do anything to me.” Regardless of their stance, undocumented Latinx millennials often demonstrate incredible resilience in the face of both racism and anti-immigrant sentiment.

Recommendations

What are the solutions to these racial and spatial microaggressions? Latinxs are at risk for racial microaggressions when they are in White neighborhoods, cities, and settings.

- The burden to fix the problem relies on those who hold privilege. In this case, White allies and others witnessing racial microaggressions can intervene in oppressive situations. The challenge is some microagressions are subtle; they are harder to combat for the target and for allies to identify and intervene.

- Educators can also have one small role in this by engaging with students about microaggressions before encouraging or requiring students to participate in off-site events. The answer is not avoiding White space; instead, the task is to critically think about how oppression can be experienced spatially. Similarly, educators may also need to reflect and rethink off-site events that may be off limits for undocumented students who are unable to travel outside of the United States. Undocumented students also may understandably want to avoid locations that are near the border, require travel through U.S. checkpoints, or are legally and socially hostile to immigrants.

- Instructors can also have class discussions about how stereotypes or “controlling images” (Collins, 2005) perpetuated in the media can shape damaging ideas about people of color. As Cecilia’s experience makes clear, racial microaggressions come to life in part because of societal messages about the worth of Latinxs in U.S. society.

- Furthermore, instructors can also think about integrating assignment or class discussion prompts about local space and students’ experiences of microaggressions. Using maps, as well as resources on residential segregation (such as http://demographics.virginia.edu/DotMap/), can encourage fruitful discussions about how racial microaggressions are experienced in local communities. Such conversations could also be an opportunity to brainstorm meaningful ideas about how to address local spaces of (non)belonging.

Future Research

I suspect that although my research was completed in Los Angeles, the experiences I have captured are not exclusive to this locale. Recent research by Flores-González (2017) suggests that Latinx millennials in Chicago are also experiencing the racial politics of space in similar ways. Scholars can continue to explore these issues of spatial and racial microaggressions by extending this research to other regions and by including the voices of other millennials of color. As I did here, other researchers might examine how intersecting social identities become more or less salient depending on the spatial and legal context.

References

- Ballinas, J. (2017). Where are you from and why are you here? Microaggressions, racialization, and Mexican college students in a new destination. Sociological Inquiry, 87(2), 385–410.

- Collins, P. H. (2004). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Flores-González, N. (2017). Citizens but not Americans: Race & belonging among Latino millennials. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Keels, M., Durkee, M., & Hope, E. (2017). The psychological and academic costs of school-based racial and ethnic microaggressions. American Educational Research Journal,54(6), 1316–1344.

- Minikel-Lacocque, J. (2013). Racism, college, and the power of words: Racial microaggressions reconsidered. American Educational Research Journal, 50(3), 432–465.

- Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Griffin, K. E., Davidoff, K., & Sriken, J. (2014). The adverse impact of racial microaggressions on college students' self-esteem. Journal of College Student Development, 55(5), 461–474.

- Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.

- Yosso, T., Smith, W., Ceja, M., & Solórzano, D. (2009). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate for Latina/o undergraduates. Harvard Educational Review, 79(4), 659–690.