5. Regimes of Attraction, Parts, and Structure

5.1. Constraints

In Critical Environments, Cary Wolfe, a strong defender of Luhmann's systems theory, develops an important critique of autopoietic theory. As Wolfe writes,

In point of fact, this shortcoming of autopoietic theory arises not simply with respect to social relations, but rather besets all discussions of exo-relations with respect to objects. In its focus on the operational closure of objects, the self-regulation and self-production of objects, and the manner in which objects constitute their own information, autopoietic theory tends towards a utopianism that ignores material constraints on the activity of objects when objects enter into exo-relations with other objects. In its emphasis on the closure of objects, autopoietic theory often tends towards a picture of objects in which they are completely self-determining and therefore entirely sovereign. Each object is treated as an observer that observes the world through its own distinctions, and all observers are treated as absolutely equal. For example, we encounter Luhmann saying that objects cannot be dominated. What is missed here, however, are inequalities among objects that emerge as a result of how they are related to other objects in networks.

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx observes that, “[m]en make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past”. [228] What Marx says here is true not only of human actors, but also of all nonhuman actors. In many of its formulations, autopoietic theory threatens to invert this thesis. That is, autopoietic theory tends towards a characterization of the world in which entities not only make their own history, but make their own history in conditions of their own making. What we get here is a sort of radical idealism, where every entity, by virtue of its operational closure, fully constructs its own world. As Paul Bains articulates it in The Primacy of Semiosis,

As a consequence, Bains continues, “we can begin to see that Maturana and Varela oscillate between realist claims about the nature of the individuality of autopoietic systems independent of an observer and idealist and phenomenological claims wherein thought is not able to have a real relation with something other than itself”. [230] Do Maturana and Varela contend merely that we cannot have a direct relation with other objects, or are they making the more radical claim that each object constructs all other objects? The two claims are very different. The first claim is broadly consistent with the claims of object-oriented philosophy and onticology, insofar as both hold that all objects withdraw from one another, encountering each other only on conditions of closure. The second claim seems to lead to incoherence in that it is not clear how there can simultaneously be no independent reality and be entities that construct other entities. In other words, minimally autopoietic theory requires the independent reality and existence of entities doing the construction.

However, the more significant problem with autopoietic systems theory is that in its focus on the internal functioning of the entity, it tends towards a conception of entities that carry out their functions in a purely frictionless space, where each entity is a complete sovereign encountering no constraints from the world around it. It is one thing, following Aristotle, to defend the autonomy and independence of substance. It is quite another to argue that this autonomy and independence of substance entails that when substances enter into exo-relations with other objects they nonetheless remain completely unconstrained. The absurdity of the thesis that there are no independent objects can be discerned by simply reversing Maturana and Varela's claims about observation. Are Maturana and Varela prepared to claim that they are constructed by the observations of another autopoietic system such as the tardigrade? If not, why? And if they do grant independent existence to themselves, why do they not follow Bhaskar in granting a similar autonomous existence to other objects? What we need is an account of exo-relations capable of doing justice to both the closure and withdrawal of objects as well as the constraints that other objects exercise on withdrawn objects.

In this connection, we can ask ourselves how it is possible for objects to be constrained despite their autonomy, independence, and self-determination. In many respects, it is the distinction between virtual proper being and local manifestation, coupled with the concept of regimes of attraction that allows us to theorize these constraints. For while, in their virtual proper being, objects withdraw from any of their actualizations in local manifestations, while every object always contains a reserve excess over and above its local manifestations, nonetheless local manifestations are often highly constrained by the exo-relations an object enters into with other objects in a regime of attraction.

The key point not to be missed is that while objects are only selectively open to their environments, this doesn't entail that objects are free to do whatever they might like with their environments. In the case of autopoietic systems, for example, the distinctions which organize a system's relation to its environment are more or less anticipations, selecting events that are relevant to the ongoing autopoiesis of the system. However, as anticipations, these distinctions can be disappointed and those disappointments play a role in the subsequent development of the system. What we need is a model of exo-relations that allows us to thematize these complex exo-relations between system and environment. In Difference and Repetition, Deleuze remarks that,

Deleuze here presents us with a model of objects in which the development of objects unfolds in a relation between three environments. In the case of the organism, there is the internal environment defined by the genes of the organism. In addition to the internal environment of the organism, there is the external environment of the organism defined by relations to other organisms and entities out there in the world. Finally, there is what we might call the “horizontal” environment of the organism, consisting of the internal parts of the organism and the pressures they place on one another requiring integration. When we think this threefold relation between environments, we must not forget the dimension of time and interactivity among these different domains. Development, which continues throughout the entire life of the organism, unfolds interactively and in the dimension of time, such that events in one of these environments impact events in other environments, actualizing them in aleatory ways.

Missing in Deleuze's mapping of developmental relations, however, is a role for the agent itself in its own construction. Formulated in terms of Kenneth Burke's pentad, Deleuze's map of development is all scene with no agent. Rather, the agent (object) ends up becoming an effect of the dynamics taking place in the scene (the interactions among the environments). Deleuze's mapping of exo-relations thus points us in the right direction for thinking constraints or relations of dependency in local manifestations, but suffers from treating the agent or object as a mere effect of these relations rather than granting the agent a causal role in these developmental processes. In my view, developmental systems theory (DST) provides the resources for navigating the radical constructivism of autopoietic theory where each object is a sovereign constructing all other objects, and the extreme “environmentalism” of Deleuze's mapping of ecological relations where the object is merely an effect of relations between internal, horizontal, and external environments.

Although the focus of DST has revolved around debates in developmental biology, it nonetheless provides us with a general model of how objects behave in regimes of attraction or within fields of exo-relations to other objects. DST research has focused primarily on nature/nurture debates within biology and the social sciences, strongly contesting models of genetics that treat genes as blueprints pre-delineating the eventual form that the phenotype (what I would call the “local manifestation”) of an organism will take. In her early groundbreaking work, The Ontogeny of Information, for example, Susan Oyama shows that while mainstream biology gives lip service to the interactionist hypothesis that the development of the phenotype results from the interaction between genes and environment, nonetheless biologists tend to discuss genes as already containing information that presides over the development of the phenotype as a sort of map. In contrast to this, DST theorists argue that,

Along the lines I argued in the last chapter, information is not something that exists out there in the world, but is rather something that is constituted and constructed. There is no pre-existent information in the environment, nor can it be said, in the context of genes, that genes already contain information. Rather, events that take place in the development of the organism, cell development, and protein production themselves have an effect on how genes are actualized and the activation of particular genes also impacts how other genes are actualized or set in motion. As a consequence, while genes are indeed a causal factor, they cannot be said to constitute a map or blueprint of the organism.

In the introduction to Cycles of Contingency—a collection of articles by developmental systems biologists and theorists—Oyama, Griffiths, and Gray outline six basic themes of DST research:

- Joint determination by multiple causes—every trait is produced by the interaction of many developmental resources. The gene/environment dichotomy is only one of many ways to divide up interactants.

- Context sensitivity and contingency—the significance of any one cause is contingent upon the state of the rest of the system.

- Extended inheritance—an organism inherits a wide range of resources that interact to construct that organisms life cycle.

- Development as construction—neither traits nor representations of traits are transmitted to offspring. Instead, traits are made—reconstructed—in development.

- Distributed control—no one type of interactant controls development.

- Evolution as construction—evolution is not a matter of organisms or populations being molded by their environments, but of organism-environment systems changing over time.[233]

Here it is important to note that developmental systems theorists use the term “system” in a different way than I have been using it up to this point. For the DST's, the organism-environment relation constitutes a developmental system. By contrast, within the framework of autopoietic theory, systems are one side of a distinction between system and environment.

Despite these differences, however, there are strong points of resonance between the autopoietic conception of systems and that advocated by dynamic systems theorists. Like autopoietic theorists, DST emphasizes the manner in which organisms construct their environment. The construction of the environment does not simply consist in the construction of things such as ant nests and bird nests, but also involves the way in which organisms are selectively open to their environments. As biologist Richard Lewontin observes,

In short, environments cannot be treated as something that is simply given or there such that the organism subsequently fills a niche that already existed in the environment. Rather, organisms take an active role in constructing their environment, both through determining relevancies in the environment and through actively changing their environment through activities like building nests. In terms of autopoietic theory, systems (organisms/objects) determine that to which they are open or what is relevant in the world about them. In other words, there is no such thing as an “environment as such”. Rather, we can only discover what constitutes the environment of an organism through a second-order observation of how the organism relates to the world around them.

A central axiom of traditional evolutionary biology is that “the organism proposes and the environment disposes”. Here the theory runs that random variations within the population of a species are proposed as various solutions to the problem of the environment. Individual organisms are proposed as various solutions to the problem posed by the environment. The premise of such a thesis is that the environment is something there, present-at-hand, that the organism must adapt to. This thesis, however, becomes significantly complicated when we recognize that organisms construct their own environments. Here the organism can no longer be treated as a passive object, such that genes and the environment are the subjects forming this object, but rather the organism itself becomes a “subject” that plays a role both in how its genes are actualized and how its environment is constructed. This does not entail that the organism is a sovereign acting without constraint in a purely smooth space it can define at will, but it does entail a far more active role on the part of the organism in these processes.

Lewontin goes so far in this line of thought as to argue that species actually co-construct one another. As Lewontin remarks,

Part of the reason lynxes are as they are has to do with how the properties of hares and other similar creatures have constructed them. In other words, those lynxes that were more adept at catching the speedy hare were more likely to reproduce. Likewise, we can say that hares are constructed by lynxes and other similar organisms.

One of the central themes in DST is the concept of extended inheritance. Where traditional evolutionary biology tends to treat genes as the only thing inherited by organisms, thereby leading to the neo-Darwinist thesis that genes are the true units of natural selection, DST emphasizes, how, in addition to genes, all sorts of environmental factors are selected as well. Ant larvae, for example, inherit the nest and traces of pheromones built and left by other ants. These inheritances play a role in the development of the organism’s phenotype, determining, for example, what type of ant the larvae will become (worker ant, soldier ant, and so on). Needless to say, these are non-genetic inheritances. Likewise, humans inherit culture, infrastructure, practices, and so on.

Observations such as these lead DST to defend parity in explanations and to remodel the concept of natural selection. Parity reasoning is a form of reasoning in which the theorist refuses to grant one sort of agency—for example, genes—control of development. Rather, parity reasoning emphasizes distributed causality, where a variety of different causal factors contribute to the development of the phenotype. The thesis here is not that all causal factors contribute equally to the local manifestation of the phenotype or organism, but that the interaction or interplay of a variety of different causal factors play a role in the local manifestation of the entity. This has real consequences for how research is conducted in both biology and the social sciences. In biology, for example, we might conduct experiments where we keep the environment constant to see what effects this has on the phenotype, but also conduct experiments where we vary the environment while keeping the genes constant to see what effects these shifts have on the phenotype.

Returning to some themes from the introduction, we saw how a good deal of contemporary theory focuses on the subject's and culture's relation to the world. Within this framework, the framework of representation, the subject falls in the marked space of the grounding distinction of thought. Beneath the subject or culture, we find a sub-distinction referring to content that leads us to focus on signs, signifiers, and representations. While clearly signs, signifiers, and representations play an important role in how human relations come to be organized, we can see how parity reasoning would lead us to expand the focus of our analyses in the social sciences and in social and political thought. Jared Diamond, for example, raises the question of why Western Culture has enjoyed such a dominant position throughout world history.[236] Why, for example, did the West conquer the Americas, rather than the Americas conquer the West? If we begin from the standpoint of the subject and culture, thereby indicating signs, signifiers, and representations as our sub-distinction, we are led to explain these cultural differences based on something unique to Western systems of representation or narratives that allowed the West to conquer other groups. For example, we follow Heidegger in asserting something unique and singular about the “Greek event”, or perhaps we follow the theology of Radical Orthodoxy promoted by figures such as John Milbank, locating a fundamental historical break for humanity in the “Christian event”.

Through careful analysis, however, Jared Diamond emphasizes the environmental differences between different cultures and the advantages and disadvantages these created for various people. Thus, for example, Diamond contends that there were few animals fit for domestication in the Americas. This had a profound impact on how Eurasian and American populations developed. Because Eurasian populations had far more domesticated animals, there was also a much higher degree of cross-species germ development in Eurasian history. This meant that Eurasians not only developed greater immunity to disease, but also had far more diseases in the environment. One reason European conquest of the Americas was so unilateral was precisely because there were a variety of diseases moving from Europe to the Americas without the reverse movement from the Americas to Europe. As a consequence, tens of thousands of Native Americans died, rendering the European conquest far easier in the long run. Again, the point here is not that semiotic differences make no difference, nor that disease alone (Diamond explores a variety of geographical factors) completely explain such brutal events. The point is that when we draw distinctions in particular ways, certain phenomena and causal factors become completely invisible. Diamond practices an exemplary form of parity reasoning in exploring these geographical factors. Continental social and political thought and theory needs to do a much better job in exploring the role played by non-semiotic actants such as natural resources, the presence or absence of power lines, road distributions and connections, whether or not cable internet connections are available, and so on, in their exploration of why certain social formations take the form they do.

Insofar as it is not simply genes that are inherited, but environments as well, it follows that natural selection must operate not only at the level of the organism or genes, but at the level of environments too. Here we must recall that many organisms quite literally construct their environments, building nests and so on. Those constructed environments that confer an advantage in the reproduction of the organism will tend to be selected and passed on through generations. Here it's worth recalling that Darwin nowhere specifies what the mechanism of inheritance is, only that in order for natural selection to take place there must be inheritance. There is thus no reason to suppose that genes alone are the sole mechanism of inheritance. Constructed environments such as ant nests and culture are also forms of inheritance. In their article, “Darwinism and Developmental Systems”, Griffiths and Gray give a striking example of such environmental inheritance (and a number of other examples as well). As Griffiths and Gray observe,

The point here is that the Buchnera bacteria is not a part of the aphid's genome, but nonetheless plays a significant role in the development of the phenotype. Far from the genes already containing information in the form of a blueprint of what the organism will turn out to be, genes are one developmental causal factor among a variety of others. The phenotype is plastic in the sense that it can take on a variety of different forms. Here it goes without saying that the plasticity of the phenotype isn't entirely without constraint. The organism-environment system indeed constrains the development of the phenotype in a variety of ways, defining a topological space of possible variations. What's important here is that the information presiding over the genesis of the phenotype is something constructed in the process of development from a variety of factors, and, moreover, the qualities that the organism comes to embody are not located already in the organism in a virtual or implicit form, but are rather new creations in the process of development.

In light of the foregoing, we are now in a position to theorize the emergence of constraints within an onticological and object-oriented philosophical framework. The whole problem arises from the manner in which objects are operationally closed and the manner in which they constitute their own environment through their distinctions, defining that to which they are open and that to which they are not open. This, in turn, leads to Luhmann's thesis that objects can neither be dominated nor controlled. However, while objects indeed constitute their own openness to their environment, it does not follow from this that objects control or create their own environment. Here we will recall that the environment is always more complex than the object or system that unifies the environment through a determination of what is and is not relevant to it. Moreover, while openness to the environment arises from the manner in which the object or system is organized, this openness does not determine which events take place in the environment. Were this the case, then each substance would be controlling or “dominating” the other substances or systems that exist in its environment. Just as other substances in a substance's environment can only perturb the substance without determining what information events will be produced on the basis of these perturbations, the most the substance can do is attempt to perturb other substances without being able to control what sort of information-events are produced in the other substances. And these attempted perturbations can always, of course, fail. My three-year-old daughter, for example, might yell at her toy box when she bumps into it, yet the toy box continues on its merry way quite literally unperturbed.

Everything turns on recognizing that, while objects construct their openness to their environment, they do not construct the events that take place in their environment. When Luhmann observes that objects cannot be controlled or dominated, his point is not that objects are completely free sovereigns capable of creating whatever reality they might like, but rather that any event that perturbs them will be “interpreted” in terms of the system’s own organization. As a consequence, objects cannot be steered from the outside. However, the events that do or do not take place in the environment of an object and to which the object is open nonetheless play a tremendously significant role in the local manifestations of which the object is capable. We see a significant example of this in the case of Griffith and Gray's aphids, where the presence or absence of the Buchnera bacteria makes a significant difference in the formation of the aphid's phenotype. Those other objects and events in the environment of the object define a regime of attraction with respect to the object, creating regularities in the local manifestation of the object and producing constraints on what local manifestations are possible.

Regimes of attraction should thus be thought as interactive networks or, as Timothy Morton has put it, meshes that play an affording and constraining role with respect to the local manifestations of objects. Depending on the sorts of objects or systems being discussed, regimes of attraction can include physical, biological, semiotic, social, and technological components. Within these networks, hierarchies or sub-networks can emerge that constrain the local manifestations available to other nodes or entities within the network. Thus, for example, government officials and high ranking business leaders such as CEO's have access to both contacts and business information that gives them an advantage in the capture of wealth and power. This appropriation of wealth and power leads, in its turn, to an absence of resources for those without this access. As a consequence, local manifestations at less “connected” levels of the social sphere are severely limited in terms of what is possible for them in much the same way that aphids without access to the Buchnera bacteria develop in a particular way. While the particular texture of a regime of attraction does not determine what an object will become or be because such actualizations depend on the organization of the object in question, they can play a significant role in limiting what local manifestations are possible for an object.

Similarly, in another context, Marx discusses the manner in which the repetitive activity of factory work has the effect of de-skilling the worker and dampening his or her cognitive abilities.[238] Without going into too much detail, the factory form arises, in part, as a consequence of the development of wage-labor and the necessity it engendered for diminishing the cost of production so as to maximize the production of surplus-value. The paradox of the factory form is that through de-skilling labor as a result of highly specialized and rote, repetitive activity, the laborer becomes increasingly dependent on the wage-labor system that divests him of control of his own life and circumstance, reinforcing the very system that limits his own freedom. The knowledge and skills are lost that would allow him to do other tasks. As a result, he becomes trapped in the factory system in part through his own actions. Technology here plays a central role in both this de-skilling and the diminution of cognitive ability as a result of endless repetitive activities that require little thought or skill. As such, wage-labor, the factory, and technologies function as a regime of attraction that deeply influence local manifestations at both the societal level (the texture that society takes on) and at the individual level of the worker. Different activities, regimes of attraction, and modes of production might lead to very different local manifestations at the cognitive and affective level.

Within this context, one of the central roles of social and political theory ought to be the cartography of regimes of attraction. This cartography consists in mapping those networks of objects that play a significant role in the production of local manifestations at the level of individuals, groups, and the texture of societies at large. Through such cartographies, it becomes possible to strategically locate those places where bifurcation points within the social system are available, allowing for the possibility of new local manifestations at the level of individuals and society. In this regard, Marx was an exemplary cartographer. In Capital, at least, Marx did not use “society” and “class” as explanatory variables, but instead mapped the regimes of attraction within particular historical settings precisely to explain why society takes the form it does and how class structures come to exist as they do. However, in his cartography of the social sphere, Marx sought to map not only existing social relations, but also virtual social tendencies as well. That is, Marx sought to locate those tensions and lines of flight within existing social structures to determine where change might be taking place and where new forms of social organization might be emerging. Through a knowledge of regimes of attraction, the attractors that organize them, and the bifurcation points to which they are susceptible, it becomes possible to strategize practices that might intensify and accelerate these processes. The presence of a bifurcation point is no guarantee that a system will shift into a new basin of attraction. Consequently, cartography, a cartography of the virtual, becomes an indispensable dimension of practice, providing us with resources for determining how to activate these bifurcation points.

Above all, we must avoid the conclusion that regimes of attraction determine the local manifestations of objects or entities. While regimes of attraction play a significant role in the form that local manifestations take, objects are not merely effects of regimes of attraction. When objects enter into exo-relations with other objects, these other objects certainly perturb the object in a variety of ways, influencing its local manifestations, but objects, and above all, autopoietic objects, are also causes and actors in the world. A cat that finds that the heat of the fire in the fireplace is a bit too hot does not merely sit there and roast, but rather gets up, paces back and forth a bit, and finds a place to sit more amenable to its desired temperature. In this way, the cat takes an active role in modulating the production of its local manifestations in relation to the milieu in which it finds itself. Likewise, beavers construct imposing dams, creating optimal environments for themselves to live in. While the regimes of attraction we find ourselves enmeshed in might constrain us in a number of ways, through our movement and action we have the ability to act on these regimes of attraction, construct our environments, and therefore modify the circumstances in which we find ourselves. We are not simply acted upon by regimes of attraction, but act on them as well. Given the unpredictable nature of other actors, however, the question revolves around which form of action might be most conducive to enhancing our existence.

5.2. Parts and Wholes: The Strange Mereology of Object-Oriented Ontology

Within Continental philosophy and theory, a lot of mischief has been caused as a result of failing to carefully think through issues of mereology or the relationship between parts and wholes. This has especially been the case for bodies of social and political thought deeply influenced by the structuralist turn arising out of Lévi-Strauss and a variety of other French thinkers. In its focus on social structure as a totalizing relational system without an outside, structuralism created a crisis in French social and political thought, raising questions as to how any sort of agency or social change is possible. For if structure consists in differential or oppositional relations between elements and elements cannot be said to exist independent of their relations, then the question emerges of how any action whatsoever is possible that doesn't merely reproduce the social structure. Matters were further complicated in the tendency of structuralism to treat the subject as an effect of impersonal and collective structures that function according to their own pulse and rhythm. In this connection, who can forget Althusser's pronouncements concerning the subject in “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses”? There Althusser remarks that,

Althusser's pronouncements about the subject immediately generated a crisis in French social and political theory, generating, in subsequent years, a series of responses from both his students and those deeply influenced by his thought and conception of the social.

In many respects, the problem is quite simple. If the subject is both constitutive of ideology and constituted by ideology, and if ideology is the means by which the social system “reproduces the conditions of production”,[240] then it would appear that social and political thought is unable to account for how it is possible for social change to take place. This problem emerges from the relational conception of the social developed within the various structuralist frameworks. Insofar as the relations constituting structure are themselves internal relations in which all elements are constituted by their relations, it follows that there can be no external point of purchase from which structure could be transformed. As an element of structure, this would hold for the subject as well. Like anything else within the social system, the subject would necessarily be differentially constituted by the relations making up social structure.

With these grim pronouncements, a desperate search began to find a free or void point within structure, a point not overdetermined by the differential relations constituting social structure, such that the transcendental condition under which change is possible could be articulated. Surprisingly, the theoretical resources for such an account were already suggested in the early work of Lévi-Strauss. In his early Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, Lévi-Strauss's theorization of the concept of mana suggested the existence of a paradoxical feature of structure that is simultaneously internal to structure and undetermined by structure. As Lévi-Strauss observes,

Further on, Lévi-Strauss goes on to remark that,

To this list we can add politics. What this floating signifier suggested was the possibility of a void point within structure, a point of complete indetermination, marking a space where both the social might be transformed and where the subject might exist as something more than a patient or object of social forces.

And indeed, if we look at the trajectory of subsequent French social and political theory, we see a variant of precisely this option being embraced. The later work of Althusser comes increasingly to focus on Lucretius and a discourse of the swerve and the void.[243] Rancière comes to emphasize the role of the “part of no part” as that void point within the social order (which he calls “the police”) from which the social order comes to be transformed.[244] Badiou emphasizes the manner in which every structured situation is haunted at its edge by a void where entirely novel and undecidable events can occur that a subject can then decide, inaugurating truth-procedures that gradually change the organization of the structured situation.[245] And Žižek emphasized the unrepresentable real at the heart of the symbolic from whence a subject becomes possible that marks the failure of the symbolic and such that an absolute act that completely abolishes the subject and re-creates it is open. All of these themes, developed in so many different ways, appear to be variations of the floating signifier that simultaneously marks the limit of the social and its infinite transformability.

Closely connected with this recognition of the void or floating signifier that haunts every social structure was a growing awareness of the contingency of structure. In a certain respect, the contingency of structure had been a persistent theme of structuralist thought. Where Kant had proposed one universal transcendental structure of the world issuing from the transcendental subject, structural anthropology and linguistics had revealed a variety of different structures organized in very different ways. However, increasingly structure came to be thought as veiling an infinite multiplicity bubbling beneath structure without order or unity. No one has developed this line of thought with more rigor and in greater detail than Alain Badiou in his magnificent Being and Event. There, developing an ontology based on Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, Badiou advances something of a dialectical ontology partitioned between what he calls inconsistent multiplicities and consistent multiplicities. Inconsistent multiplicities can be thought as a sort of chaos insofar as they are pure multiples without any structure or individuated entities. These multiplicities constitute being as such or being itself. Consistent multiplicities, by contrast, are structured and unified situations. Consistent multiplicities are formed from inconsistent multiplicities through an operation Badiou refers to as the “count-as-one” and, by virtue of being founded in inconsistent multiplicities, are always haunted by a chaos that bubbles just beneath the surface. As such, any consistent multiplicity is only a contingent organization of a situation.

It is not difficult to detect, lurking behind Badiou's ontology, the desire to rigorously ground revolutionary social theory. One of the main ways in which ideology functions is through the naturalization of the social world. In other words, ideology presents the structure and organization of the social world as the inevitable and natural order of things, such that other arrangements are impossible. One major form of ideological critique has thus historically taken the form of demonstrating the manner in which social formations are contingent or capable of being otherwise through maneuvers of historicization and so on. Badiou's thought provides an ontological grounding for this capacity to be otherwise. In many respects, such a conclusion is already internal to set theory. Recall that, within the framework of set theory, sets are defined strictly through their extension or the elements that belong to the set. Here we can distinguish between a set and a type based on whether or not membership in the collection is defined extensionally (by the parts that belong to it) or intensionally (by some shared feature among the elements). The collection of all dogs, for example, is a collection that is defined intensionally insofar as membership in it is a function of all elements belonging to the collection sharing a common characteristic or set of characteristics. In contrast to types, sets are collections defined purely in terms of their members, such that there is no necessity of these elements sharing a common characteristic. Nor must the elements of the set be ordered in any particular way. Insofar as sets are defined extensionally, the set {x, y, z} is equivalent to the set {y, z, x}. In short, the elements of sets are non-relational or are not defined by the relations among their elements. The point here is that if social structures are sets, there is no one way in which they can be organized and a variety of other forms of social organization are possible.

Initially these issues pertaining to set theory might seem remote from issues of ideology and the naturalization of the social field. However, if it is true that being is “set theoretical” and that, at its most fundamental level, being consists of inconsistent multiplicities rather than consistent multiplicities, then it also follows that any social structure is contingent in the precise sense that relations among elements can be otherwise. From the foregoing, this can be seen in two ways. On the one hand, because sets are defined extensionally and without any ordering relations among the elements, it follows that there is no necessary relation among the elements. Here relations are external to their terms. Likewise, a similar point can be made through the power set axiom in set theory. The power set axiom allows us to take all possible subsets of a set, forming a new set out of this collection. Thus, for example, given a set {x, y, z}, its power set would be {{x}, {y}, {z}, {x, y}, {x, z}, {y, z}, {x, y, z}}. The power set can then be applied recursively yet again to generate an even larger set and so on. The “cash value” of the power set axiom at the level of ideology critique is that it reveals the manner in which social groupings are contingent and capable of being otherwise by being grouped in different ways. In effect, Badiou provides an ontological “foundation” for demonstrating the contingency of social relations, thereby underlining the manner in which they are always capable of being structured otherwise.

Through this maneuver, Badiou strikes a strong blow against the internalism of structuralism. Structuralism had argued that all relations are strictly internal to their elements, such that elements cannot be said to have any existence independent of their relations. Through an ontology of inconsistent multiplicities coupled with an account of the externality of relations, Badiou is able to show that while elements do indeed enter into temporary relations with one another, these relations are always and everywhere necessarily contingent and capable of being otherwise. As such, Badiou significantly broadens the possibility of our ability to think change within the social sphere, while also allowing us to maintain the best insights of structuralism through his account of consistent multiplicities.

Badiou's meditations on the relationship between sets and subsets is thoroughly mereological in character. In making claims about the extensional composition of sets (parts), Badiou underlines the manner in which the parts of a set are simultaneously objects in their own right while also being parts of larger objects, to wit, the sets from which they are drawn. What is interesting here is that the parts are not defined by their relations to other elements in the set, but are objects of their own that can be detached from their membership in the set. Here object-oriented ontology and onticology find an unexpected ally with Badiou and a surprising point of resonance. As we have already seen, Graham Harman argues that all objects are such that there are objects wrapped in objects wrapped in objects, such that we can simultaneously treat objects as relations among objects and discrete units in their own right. Badiou argues—and, I might add, argues well—that all sets are infinite in the sense that they are infinitely decomposable. This is the dimension of inconsistent multiplicity haunting every consistent multiplicity.

What we encounter here is what I call the “strange mereology” of onticology and object-oriented philosophy. Mereology is that branch of mathematics, ontology, and logic that studies the relationship between parts and wholes. The study of mereology is highly complex and formalized, however onticology and object-oriented philosophy are concerned with a particular mereological relation; namely, that relation between objects where one object is simultaneously a part of another object and an independent object in its own right. To understand why this mereology is such a strange mereology, we must recall that all objects are independent or autonomous from one another. Objects can enter into exo-relations with one another, but they are not constituted by their relations. Put differently, their being does not consist of their relations. Consequently, the strangeness of this mereology lies in the fact that the subsets of a set, the smaller objects composing larger objects, are simultaneously necessary conditions for that larger object while being independent of that object. Likewise, the larger object composed of these smaller objects is itself independent of these smaller objects.

Despite profound points of overlap between Badiou's mereology and the mereology advocated by onticology and object-oriented philosophy, there are nonetheless important points of divergence between the two ontological frameworks. While both Badiou and onticology and object-oriented philosophy endorse an extensionalism of relations between objects, onticology and object-oriented philosophy endorse an intensionalism of relations within individual objects. In short, objects are not merely aggregates of other objects, but have an irreducible internal structure of their own. However, it's important to note that the intensionalism advocated by onticology and object-oriented philosophy is not an intensionalism revolving around a predicate shared by a plurality of objects, but is rather an intensionalism pertaining to the relations composing the internal relations of an object. To avoid confusion, I thus follow Graham Harman's convention of distinguishing between “domestic relations” and “foreign relations”. Domestic relations are relations that structure the internal being of an object and correspond to what I have called “endo-relations” in chapter 3. Foreign relations, by contrast, are relations an object enters into with another object and which I have referred to as “exo-relations”. Foreign relations are external to objects in the sense that objects are not constituted by exo-relations and can be detached from these relations. Of course, such detachment can also bring about less than happy local manifestations. If I am launched into outer space by a giant catapult without any sort of life-support suit, I will undergo a local manifestation that freezes me solid and kills me. Domestic relations, by contrast, are those relations that constitute the internal being of an object, its internal structure, and therefore the essence of an object.

Where Badiou sees sets or objects as possessing only foreign relations among the elements composing the set—e.g., {x, y, z} is equivalent to {y, x, z}—onticology and object-oriented philosophy insist that objects contain domestic relations such that their elements cannot be related in any old way. I will have more to say about this in the next section, but for the moment it is sufficient to note that Badiou's account of the relationship between inconsistent and consistent multiplicities generates special problems for his ontology. I have already discussed some of these problems in the first chapter when addressing those ontologies that argue that being is composed of chaos or a one-All that is then subsequently carved up into units. A similar problem emerges with respect to Badiou's ontology concerning the question of just how the transition from inconsistent multiplicities without unity or one to consistent multiplicities that are unified such that “one-ification” takes place. To explain this transition from inconsistent multiplicity to consistent multiplicity, Badiou refers to operations of the “count-as-one”. These operations somehow effect both a selection and a unification of elements within the field of inconsistent multiplicity, producing consistent multiplicities. Two questions emerge here: first, what is the agency that carries out this operation, and second, exactly how does this agency accomplish this feat of both making selections from the field of inconsistent multiplicity and producing unified collections? Despite the advancements of Logics of Worlds, it is my view that the answers to these two questions are significantly underdetermined in Badiou's ontology.

By contrast, object-oriented ontology begins with the premise that the world is composed of distinct entities or units, each of which has its own internal structure or set of endo-relations. The twist is that larger scale objects can emerge from smaller scale objects and larger scale objects are composed of smaller objects. Similarly, larger scale objects can break apart into a plurality of other independent objects under certain circumstances. Thus, while onticology maintains that there are ordering relations, domestic relations, or endo-relations among elements within an object, it also argues that larger scale objects contain autonomous smaller scale objects. In this connection, what constitutes the substantiality of a substance is not the parts that compose it, but rather the organization, domestic relations, or endo-relations presiding over the organization of these parts.

A variety of examples can be marshaled in defense of this thesis. Organic bodies, for example, continuously lose cells and generate new cells. Although a body cannot exist without its cells, it is clear that bodies cannot be reduced to their cells either. What constitutes the substantiality of a body is not its cells, but its organization or its endo-relations. This point might be readily granted, yet someone might object that while bodies and cells are distinct, it is a mistake to suggest that cells are independent objects in their own right insofar as cells only exist within bodies. However, this is not true. On the one hand, we can think of the various forms of cancer as relations between a body and its cells in which cells have begun to act autonomously. Likewise, organ transplants are dependent on the possibility of cells being separated from bodies. Recently, scientists in Surrey, England have created a monstrous hybrid of organic life and machine, splicing a certain number of rat brain neurons into a computer chip that sends radio messages to a robot that can sense the world and that develops pattern and cognitive skills over time.[246]

Various forms of social relations have this structure as well. The citizens of the United States, for example, are born, die, and sometimes renounce their citizenship, yet the United States continues to exist. While it is certainly true that the United States would not exist at all without any citizens, it cannot be equated with its citizens. Additionally these citizens must be linked in some way. In Imagined Communities, for example, Benedict Anderson shows how print culture, among other things, contributed to the formation of national communities. [247] My only caveat here would be that these entities aren’t imagined, but are, once built, real entities in their own right. Moreover, the United States cannot be equated with a particular geography either. The United States was the United States when it was just thirteen small colonies. Similarly, were some sort of national catastrophe to occur, the United States would remain the United States even if located solely on an island like Hawaii, or, more radically, even if citizens scattered all over the world maintained its existence through the internet. Moreover, the citizens of the United States are not just elements of the United States, but are autonomous entities in their own right. They can plot against the United States, seek to bring about the demise of the United States, renounce their citizenship, and engage in many activities not related to how they are counted as citizens of the United States.

From a certain perspective it can thus be said that all objects are a crowd. Every object is populated by other objects that it enlists in maintaining its own existence. As a consequence, we must avoid reducing objects to the manner in which they are enlisted by other objects precisely because the objects enlisted are always themselves autonomous objects. Another way of putting this would be to say that there is no harmony or identity of parts and wholes. Parts aren't parts for a whole and the whole isn't a whole for parts. Rather, what we have are relations of dependency where nonetheless parts and wholes are distinct and autonomous from one another. In this respect, we must reject the thesis of holism. Latour remarks that when one object enlists another “the two join together and become one for a third [object]”.[248] While I do not go as far as Latour in claiming that every relation between objects generates a third object, the important point is that the object that emerges out of other objects does not erase the objects out of which it is composed, but rather generates a third autonomous object related to these other autonomous objects. For example, if we treat romantic relationships and friendships as objects we must ask how many objects are before us. For the sake of simplicity, we can say that the romantic relationship is composed not of two objects, but of three objects. Here you have the two people involved in the relationship, as well as the amorous relationship itself. The amorous relationship is an object independent of the two persons in the amorous relationship. While initially this sounds very strange, we should here recall how couples talk about their relationships. They talk about being in a relationship, about how the relationship is going well or is in a state of crisis. Likewise, friends of couples often treat couples as units, behaving as if one person cannot be invited to dinner without inviting the other. Similarly, from a legal standpoint, a person is married regardless of whether or not she has renounced the marriage or has decided to step out on her spouse. In all of these cases, the relationship is an autonomous object that has an existence over and above the persons that it enlists in its own continuing existence.

The relationship between multiples and sub-multiples or larger scale objects and smaller scale objects is one in which sub-multiples provide constant perturbations to multiples and where multiples perturb sub-multiples. Each object is an operationally closed object that relates to the sub-multiples of which it is composed or the multiples that it composes only in terms of its own internal organization. Sub-multiples and multiples are only “interested” in one another in terms of the perturbations they provide for one another with respect to their own respective autopoietic processes. The United States, for example, only relates to American citizens qua citizens, being exclusively concerned with things such as taxes, votes, positions on a variety of issues determining strategies for Congress and administrations, whether or not their action is legal or illegal, and so on. Most of the things that occupy the personal life of individual citizens are completely invisible to an object such as the United States and are treated as mere noise. The United States, for example, is completely oblivious to what I cooked for dinner last night or the fact that I am now sitting on the floor before my computer. Put in terms of Spencer-Brown's theory of distinctions, things like what I had for dinner last night belong to the unmarked state of the distinctions deployed by the United States in defining its channels of openness to its environment. These are events that cannot perturb or “irritate” the United States in its processes of producing information.

These relations between multiples or larger scale objects and sub-multiples are thus relations of what Maturana and Varela refer to as “structural coupling”. As they describe this relation, “[w]e speak of structural coupling whenever there is a history of recurrent interactions leading to the structural congruence between two (or more) systems”.[249] In short, structural coupling is a relation in which two or more objects constantly perturb or irritate one another, thereby making contributions to the local manifestations of each other and the evolutionary development of one another. The key point here is that while these systems or objects perturb or irritate one another, each system relates to these perturbations according to its own organization or closure such that we can't treat relations between objects as simple input/output relations.

Because objects are operationally closed and are composed of other objects, it follows that tensions or conflicts can emerge between multiples or larger scale objects and sub-multiples or smaller scale objects. As Latour writes, “[n]one of the actants mobilized to secure an alliance stops acting on its own behalf [...]. They each carry on fomenting their own plots, forming their own groups, and serving other masters, wills, and functions”.[250] Here it could be said that each object contends with its own system-internal entropy arising from the surprising and dissident role that other objects play within it. In enlisting other objects to produce them, larger scale objects must contend with the tendencies of other objects to move in other directions and act on behalf of other aims. Each object therefore threatens to fall apart from within, to have the endo-relations presiding over its own organization destroyed, and therefore must develop negative feedback mechanisms to maintain its own structural order.

For example, if a class is an object, the professor, an element or sub-multiple of the class, might conduct him- or herself in a way different from his or her prescribed role as professor, teaching nothing at all, talking about unrelated things, relating to students in inappropriate ways, and so on. In these circumstances, some or all of these students or perhaps administrators might relate back to the professor in such a way as to steer him or her back to his role as a professor. Indeed, today one major administrative trend in academia is to formulate ways of gauging the performance of professors by selecting samples of student work as well as student evaluations. At a higher system-specific level, these are ways in which the administrative level increases its capacities to be “irritated” or “perturbed” by classes that are difficult to directly observe on a day to day basis. Based on these ways of constructing openness to an inaccessible environment, administrations devise techniques to steer faculty or introduce negative feedback into the classroom that strive to normalize or codify academic standards and techniques. Meanwhile, many faculty who are called upon to construct educational rubrics for these purposes try to structure them in such a way as to minimize the intervention of administration into their classroom and while appeasing the desire of administrations to have a spread sheet that shows their institution is successfully instructing students. In other words, we get relations of counter-feedback where faculty attempt to steer administrations in such a way as to keep them out of their business. In this instance, we can see the operational closure of two distinct systems, the classroom and administration, that do not so much communicate with one another but rather produce very different information based on perturbations with respect to one another.

Returning to the themes with which I began this section, we can see that the issues of social change are far more complex than is suggested by both structuralist thought and the heirs of structural thought. On the one hand, I believe that Althusser and his heirs tend to over-estimate the role that ideology plays in reproducing the conditions of production. While it is certainly true that “subjects” can internalize ideologies and therefore act to “reproduce the conditions of production”, the role that negative feedback plays in larger scale objects such as social systems, coupled with problems arising from operational closure, play at least as great a role if not a greater role in explaining why certain social systems tend to reproduce themselves in such a way that they are resistant to change. Moreover, we cannot blithely reduce subjects to effects of social structure. While social structures, like any other system or object, indeed constitute their own elements, it is also important to recall that they do so from other systems or objects outside the system itself. That is, they draw on systems in their environment as the “matter” out of which they produce their elements. However, these systems are themselves operationally closed, governed by their own distinctions and organization, and thus can never be reduced to mere elements within a higher order system. The result, as social and political theory inflected by Lacanian psychoanalysis has constantly reminded us, is that subjectification is never complete or entirely successful. Nonetheless, within the framework of activist politics, groups, which are themselves objects within larger scale objects such as societies, find themselves beset by negative feedback issuing from these larger scale objects that tend to stand in the way of producing the sort of change for which these groups aim.

Returning to the theme of ideology as only one element among others explaining why social systems take the form they have, we must not forget that individuals or psychic systems exist in regimes of attraction that might severely limit or impede their capacity for action. For example, a subject might very well know that he is getting a raw deal, that the political and social system within which he is enmeshed functions in such a way as to disproportionately benefit the wealthy and powerful, diminishing his wages, quality of life, benefits, and so on. However, such a subject must also eat, especially if he has a family, and must therefore have a job. In order to have a job, such a subject must have a place to live so as to eat, rest and be presentable, must have transportation, very likely requires a phone, etc., etc., etc. As a consequence, such a subject finds himself trapped within a regime of attraction and a form of employment that, while unsavory, is required for his existence. Taking action against such a system might very well amount to cutting off the very branch the person is sitting on to sustain his own existence. In this connection, I suspect that people are far more aware of the manner in which the cards are stacked against them by the broader social system and far less “duped” by ideology than one might initially suspect.

Similar observations can be made with respect to how people are dragging their feet with respect to responding to the growing environmental crisis. Here we are trapped between an awful knowledge that the environment is changing in ways that might very well affect human existence in a radical way and a social structure that is organized in such a way that nearly everything required for mere existence carries a significant carbon footprint. We need some form of transportation to get to work and, absent affordable electric cars or some equivalent, are therefore trapped within a system dependent on fossil fuels. We do not produce our own food and, due to the de-skilling of labor that has arisen as a consequence of the functional differentiation of society, are largely unable to do so on a scale necessary to sustain a family. Thus, we are dependent on food transported by vehicles that run on fossil fuels and that is produced in a way that harms our environment. Likewise, electricity, largely produced by fossil fuels, is now a necessity of life. Meanwhile, the broader social system is structured in such a way that it is very difficult to persuade politicians to change regulatory standards for industries like trucking to invest in alternative energies and so on because such changes would be detrimental to large businesses that both create jobs (which translate into votes) and which line the pockets of politicians through the campaign contributions they require to get re-elected. Closely related to this, we might note that many politicians enter the private sector as lobbyists and consultants after their terms of office, getting paid handsomely for the access they have to other politicians and agencies. Faced with the option of low-paying activist work that improves the world and high-paying consultant and lobbying work that largely benefits big corporations, they tend towards the latter and most likely are thinking about such a future while they’re in office.

Finally, questions of political change are constantly beset by issues revolving around resonance between systems. Resonance refers to the capacity of one system to be perturbed or irritated by another system. As we saw in the last chapter, because systems or objects are operationally closed such that they only maintain selective relations to their environment, they can only see what they can see and cannot see what they cannot see. Most importantly, they cannot see that they cannot see this. Niklas Luhmann has argued that modern society is functionally differentiated (legal system, media system, economic system, and so on), such that it contains a variety of different subsystems each organized around its own system/environment distinction within the social system. In addition to these function systems, society is also inhabited by various groups that become objects or systems in their own right, organized around their own system/environment distinctions.

As a consequence of this, one of the major issues facing any collective seeking to produce change within a social system is that of how to produce resonance within the various subsystems in the social system. This issue can be seen with particularly clarity in terms of how the 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) protests were reported by the media system in the United States. While there was indeed a great deal of reporting on these protests, one curious feature of this reporting in televisual media was that there was very little discussion of just what was being protested and why it was being protested in cable and network news. Rather, viewers were presented with images of massive throngs of people and acts of vandalism protesting the WTO, while being told little in the way of just why these activists were protesting the WTO. The positions and complaints of the protestors were almost entirely absent from media coverage. As a consequence, the manner in which the message resonated within the media system ended up working, in many respects, counter to the aims of the protestors. Within the media system, the protestors were coded or portrayed as anarchistic hooligans with no respect for private property and as “dirty hippies” filled with the enthusiasm of youth and its accompanying immaturity. There was next to no analysis of the protestor's arguments against how the WTO places countries in massive debt, forcing them to privatize various industries and local resources, bringing about massive environmental exploitation and the oppression of indigenous peoples, thereby causing a severe decline in wages and quality of life. Nor was there any discussion of how similar dynamics are occurring in “first tier” countries, causing significant inequalities of wealth and diminishing the ability of average citizens to represent their interests within the political system. In many respects, we can thus say that the manner in which the WTO protests perturbed or irritated the media system and the way in which those perturbations were transformed into information ended up working contrary to and against the very aims of the protestors. Within the psychic systems inhabiting the broader social system and coupled to the media system, it is likely that the protestors resonated as an anarchic threat against which the social system needs to be defended.

Similar points about system resonance or the lack thereof can be made with respect to the notorious response of the United States government to Hurricane Katrina. Everything about the government’s delayed response to the events that were unfolding in Louisiana and New Orleans suggests that there was a lack of resonance between the political system and what was unfolding on the ground. Given the detail and pervasiveness of the reporting of these events in television and print media, this is difficult to believe yet, without such a thesis, it is difficult to account for how the Bush administration could have acted in a way so contrary to its own political interests. Here we should recall that the environment of a system or an object is always more complex than the system itself. As a consequence, there is much in a system's environment that a system cannot observe or register. The events following Hurricane Katrina suggest a form of system-closure at the level of government and administration that was structured in such a way that these entities lacked the capacity for resonance with these features of the environment occurring in both New Orleans and Louisiana and the media system. This lack of resonance with the media system is particularly difficult to explain. However, if we recall that within conservative circles the media has been branded as biased by liberal ideology and that the Bush administration had taken many steps to manage the media and control their access to government, it becomes plausible to conclude that the then current administration and Congress had ceased observing the media and instead created an “echo chamber” that severely diminished their openness to the environment.

In the Critique of Cynical Reason, Peter Sloterdijk argues that cynicism has become the new form of dominant ideology.[251] Cynicism differs from traditional ideology in that where traditional ideology is a false belief about the world and social relations, cynicism has a true knowledge of social relations, power, exploitation and so on, yet continues to participate in these oppressive forms of social structure as before. As Žižek puts it, “[t]he cynical subject is quite aware of the distance between the ideological mask and the social reality, but he nonetheless still insists upon the mask. The formula, as proposed by Sloterdijk, would then be: 'they know very well what they are doing, but still, they are doing it”.[252] From this, Žižek concludes that ideology resides not at the level of what subjects know, but of what subjects do. In other words, if we are to locate ideology, we ought not look at the level of their beliefs, but at the level of their actions.

In his treatment of society at the level of ideology, Žižek returns social analysis back to the domain of content, meaning, or signification. Recalling figure 4 from the introduction, we can see that Žižek's engagement of the social structure is organized around the culturalist or humanist schema:

Within the field of this distinction, the subject or culture falls in the marked space of distinction and we get a sub-distinction where all other entities in the world are comprehended or related to as vehicles for signs, signifiers, meanings, discourses, narratives, or representations. To analyze a cultural practice or artifact according to this structure of distinction is thus to focus on its meaning-content in some form or another. Nonhuman objects and entities qua nonhuman objects and entities thereby fall into the unmarked space of the distinction.

Putting a finer note on this point, we can say that the culturalist or humanist approach to the world of objects treats any differences objects might contribute as signifying or representational differences. By way of analogy, we can say that the culturalist schema of distinction thinks about nonhuman objects in much the same way that we might think about the relation between a movie screen, a projector, and the images that appear on that screen. Objects are reduced to the status of screens and culture or subjects are treated as projectors. The only thing that becomes relevant to the analysis of social formations is thus the images that appear on the screen and how they are cultural or subjective projections. As a consequence, non-signifying differences contributed by nonhuman objects or actors are largely excluded from the domain of social analysis. Indeed, within the culturalist framework, objects aren't actors at all but are merely screens for the projection of human meanings and representations.

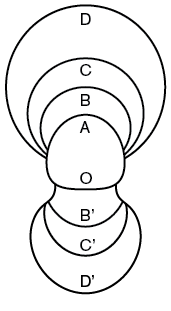

Within the framework of onticology and object-oriented philosophy, by contrast, we get an entirely different structure of distinction:

Here objects fall into the marked space, such that being is composed of only one sort of thing: objects or substances. While objects or substances, no doubt, differ from one another, being is nonetheless composed entirely of substances. As a consequence of this shift, we now encounter a subdistinction where subjects, culture, and nonhumans are placed on equal footing. In short, nonhuman actors are no longer treated as an opposing pole necessarily related to culture or human subjects, but rather are treated as autonomous actors in their own right. Thus, while we can and do indeed have relations between humans and nonhuman objects, these relations are no more privileged than relations between nonhuman objects and nonhuman objects. Moreover, insofar as nonhuman objects are themselves actors or agents, they can no longer be treated as passive screens for human and cultural projections.

In light of the foregoing, I hope it is now evident as to just why this redrawing of distinctions is of such crucial importance. Because the culturalist model of distinction places nonhuman actors or objects in the unmarked space of its distinction, regimes of attraction become largely invisible. Likewise, because the culturalist model focuses on content within the marked space of its sub-distinction, questions of resonance between systems or objects become largely invisible. The point is not that we ought not to analyze ideology or content, but that the manner in which we have organized our distinctions renders all sorts of other objects crucial to why society is organized as it is invisible or outside the space of discourse. As a consequence, we deny ourselves all sorts of strategic possibilities for engaging with the social world around us. In this regard, it is not enough merely to debunk the “ideological mystifications” from which we suffer. It is additionally necessary to raise questions and devise strategies for enhancing the resonance of other systems or objects within the social sphere so that change might be produced. Similarly, in his recent “Compositionist Manifesto”, Latour proposes the practice of composition as an alternative to critique. Where critique aims at debunking, composition aims at building. Where critique focuses on content and modes of representation, composition focuses on regimes of attraction. If regimes of attraction tend to lock people into particular social systems or modes of life, the question of composition would be that of how we might build new collectives that expand the field of possibility and change within the social sphere. Here we cannot focus on discourse alone, but must also focus on the role that nonhuman actors such as resources and technologies play in human collectives. For example, activists might set about trying to create alternative forms of economy that make it possible for people to support families, live, get to work, and so on without being dependent on ecologically destructive forms of transportation, food production, and food distribution. Through the creation of collectives that evade some of the constraints that structure hegemonic regimes of attraction, people might find much more freedom to contest other aspects of the dominant order.

The point here is that the failure for change to occur despite compelling critiques of the dominant social order cannot simply be attributed to ideological mystifications. Social and political thought needs to expand its domain of inquiry, diminish its obsessive focus on content, and increase attention to regimes of attraction and problems of resonance between objects. The social space is far more free and informed than the structuralists and neo-structuralists, in their focus on content, acknowledge and it is more likely that the lack of change arises not from subjects being ideologically duped alone but from the manner in which we are entangled in life. It is not by mistake that often profound social change only occurs when the infrastructure of social systems encounter profound collapse, for in these circumstances psychic systems no longer have anything left to lose and live in the midst of a situation where the regime of attraction in which they once existed has ceased to be operative. Observations such as these teach critical theorists something important, yet the message of these events seems to be received with deaf ears. It is not an accident, for example, that the Russian Revolution took place in the middle of massive economic crisis and World War I. What examples such as these teach us are that content alone is not enough and that political theorists need to enhance their capacity of resonance with respect to nonhuman actors and regimes of attraction.

5.3. Temporalized Structure and Entropy

As we discovered in the last section, every object is threatened from within and without by entropy such that it faces the question of how to perpetuate its existence across time. Entropy refers to the degree of disorder within a system. Suppose you have a tightly closed glass box and somehow introduce a gas into it. During the initial phases following the introduction of the gas into the system, the gas will be characterized by a high degree of order or a low degree of entropy. This is so because the particles of gas will be localized in one or the other region of the box. However, as time passes, the degree of disorder and entropy within the system will increase as the gas becomes evenly distributed throughout the box. In this respect, entropy is a measure of probability. If the earlier phases of the gas distribution indicate a lower degree of entropy than the later stages, then this is because in the earlier phases there is a lower degree of probability that the gas will be localized in any one place in the box. As time passes, the probability of finding gas particles located evenly throughout the box increases and we subsequently conclude that the degree of entropy has increased.

In many respects, the real miracle is not that change takes place, but rather that change is not more frequent. This is especially mysterious in the case of higher-order or higher-scale systems or objects such as social systems. How is it that they maintain their endo-consistency or organization across time, such that they don't disintegrate into a high degree of entropy? Put differently, why do such objects not dissolve as objects? In what follows, I focus on Luhmann's analysis of the relationship between structure, complexity, entropy, and time as it pertains to biological, psychic, and social objects. I leave the analysis of structure and entropy as it functions in nonliving objects to others, noting that when suitably modified by an object-oriented framework, the work of DeLanda and Massumi is particularly promising in this connection.

There are a number of reasons that Luhmann's conception of structure is particularly promising. First, the tendency of structuralism was to fall into a sort of structural imperialism arising from a failure to note the manner in which systems distinguish themselves from their environment or are withdrawn. Structure became a sort of net thrown over the entire world without remainder or outside. To be sure, structuralists recognized that something other than structure exists, yet were unable to articulate what this might be because of the manner in which we are always-already situated within structure such that everything we might encounter is overdetermined by structure. This schema posed very difficult questions for structuralist thought with respect to the question of how change takes place. The structuralists recognized that structures are organized synchronically and evolve diachronically, yet were left without the means of accounting for just how this diachronic evolution takes place because their doctrine of internal relations, coupled with their formalism, prevented them from appealing to any outside as a mechanism of change. As a consequence, the development or evolution of structure became thoroughly mysterious.