Mapping Women’s Revolutionary Control of Their Environment & Property in Marseille: A Digital Mapping Project

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

My original impetus for this article focused on women and property rights in eighteenth-century Marseille by investigating revolutionary tax and census records to add to what we know from notary records and dowry agreements; from court records, such as pre-revolutionary judicial petitions for séparations de corps et de biens (physical and financial separation) or séparations de biens (separation of finances only); and from divorce and family court records during the French Revolution.[2] Tax records seemed very promising because of the rich socioeconomic and geographic data that would allow for interactive digital mapping of women’s property income, their marital status, and the location of their property. Mapping is a tool that I began exploring for a spatial understanding of women’s geopolitical engagement in local and regional contexts and how women from various social milieus used their familial, social, and economic networks to influence the development of revolutionary consciousness, culture, and practices in Marseille.[3] The current project explores how geographical mapping of female-headed households and women’s property income indicated in census and tax records provides insights into revolutionary households, the changing nature of domestic authority, and the disruptions in family patterns and practices.

Susanne Desan’s work examining French revolutionary court records and potential gains for women under the French revolutionary legalization of divorce and under the increasingly egalitarian inheritance laws demonstrates how such changes empowered women but also created divisions within families.[4] Beyond the effects created by revolutionary changes in family laws, Liana Vardi’s work on the elimination of guilds in 1791 shows the chaos created as revolutionaries, in the period from 1789 on, questioned their retention of special privileges in light of revolutionary goals of freedom and equality.[5] The elimination of guilds served as another type of disruption in daily living arrangements as well as a challenge to patriarchal authority in the household.

Although women are documented fairly frequently in the tax records gathered for 1792 and 1793, analysis revealed many duplicate tax records. Ultimately, there were not as many women identified as receiving rental income from their properties as it first appeared. Census records, however, contain a wealth of household and socio-economic data about women and the varied household compositions they lived and worked in. Census takers also sometimes included declarations, identifying individuals either on or off site as the propriètaires (property owners). As a result, I focus on what census records reveal about women’s control of domestic space and ownership of property in Marseille’s urban households. The current study also analyzes mandated declarations of contributions mobilières (income not derived from commerce or land) for the six of twenty-four urban sections sampled. Preliminary research indicates that women’s control of property and household space varied by area of the city. Geospatial mapping helps illustrate the broad shifts and patterns for urban women from a variety of socioeconomic positions in controlling their day-to-day living environment.

The first census for France began as part of revolutionary changes in 1791, and to date I have found no analysis of census records in terms of women’s control of revolutionary households.[6] Michel Vovelle used census records for statistical analysis of twenty-one of Marseille’s thirty-two Section assemblies, which originally convened as the primary assemblies for elections to the Estates-General in 1789 and became active in 1790 as general debating assemblies.[7] He focused on Marseille’s urban sections, using mapping for a social and political analysis of sans-culottes’ political engagement between 1791 and 1793, especially during the Federalist rebellion, when Marseille rejected the leadership of the National Assembly. To date no similar study has emerged for women. I focus on census records between 1792 and 1793 to understand the ways in which women could control their environment via the composition of households where women lived as owners, renters, and primary renters subletting to others. Census records reveal varied family and non-family household compositions and a mix of social ranks and professions living together. The contributions mobilières gathered yielded small sample sizes from Sections 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, and 11. I have supplemented the data using the corresponding Sections’ census records between 1792 and 1793.[8] Marseille was the second largest city in France with a population of roughly 106,000 inhabitants and local archives hold extensive census records.[9] Sections 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, and 11 represent a population of roughly 13,785, which is a snapshot of 13 percent of the total population. Sources reveal that bourgeois, artisanal, and skilled laborers figure prominently in female-headed households, including singletons living outside of familial constructs.

My research relies on two different methodologies: analyzing women through property ownership, and as heads of household broadly defined. I look at the types of property that women owned, but also at household compositions for owners and renters, including marital status, children and other relatives, and employees or servants living in the household. In analyzing household compositions, I employ a non-traditional use of "head of household" to include both women and men in the census (outside its historical legal definition) to think about other ways that women controlled property. The composition of urban households varied considerably, and the concept of head of household in my work takes into consideration that individuals living in a house might be: property owners outright; the principal lessee; renting a room or a floor; living with or without family members; or living and working in the household as the employer or the employee. As a result, I go beyond legal definitions by also attributing women’s ability to head households and to have control over one’s interior space in mixed residences by looking at female singletons (widows, unmarried women, and women with no marital status) where it is clear women are not under the authority of a male/female relative or employer in their personal residence. I apply the same application of "head of household" to males living under the same conditions in the census in order not to skew the analysis. In this way, census records help us to explore female independence and autonomy for married, widowed, divorced, abandoned, and unmarried women, and those without marital status defined in the census.

My working definition of "head of household" parallels work by Rolf Gehrman who comparatively analyzes women as heads of household in census records for Germany and France in 1846. Gehrman’s approach focuses on women in “temporary or permanent function as heads of household” and analyzes marital and socioeconomic conditions “favourable to the formation of female-headed households.”[10] Part of what informs the latter analysis is how the 1846 census records show that “households are clearly separated and the relationship of each person to the head of the household is indicated explicitly or implicitly.”[11] Similar to the census data set Gehrman analyzes, Marseille’s revolutionary census records listed the vast majority of individuals with their age, profession, and marital status, and the varied family and non-family urban household compositions. Hannah Callaway found for eighteenth-century Paris many types of living arrangements existed:

Employers and their employees often shared housing; ...many servants lived in their masters’ homes. It was also common for master artisans, such as seamstresses, to lodge apprentices or journeymen in their homes. Though men and women both exercised trades, women were more likely to do piecework out of their homes, whereas men either lived with the master craftsman who employed them or ran their own shop. Workers who couldn’t afford their own apartment or who had only recently arrived in Paris shared furnished rooms in boarding houses. Households could also contain multiple generations of family or a random assortment of relatives, as young people arriving in the city moved in with a sibling, cousin, or other family member. Intergenerational households were quite common in noble families, where young married couples often lived with the wife’s family. Overall, more women lived in the city than men, mostly because the majority of servants were female. Young, unmarried women were more likely to live with their families as their sexuality was policed more heavily than that of young, unmarried men, who were apprenticed and lived with their employers. Older unmarried or widowed women sometimes lived alone, but also commonly shared space with other women, either employees, lodgers, or relatives, in small household arrangements.[12]

Julie Hardwick’s analysis of working women, gender, patriarchy and the law in early modern France unpacks how “[o]rdinary men and women as well as elites played their roles in shaping the culture of their society; they were not simply passive recipients of a trickled-down version of patriarchy put forward by rulers” and argues that “[t]he actions and perceptions of officials, family members, and others constructed a complex, negotiated, and contested household gender hierarchy that was a basis of social and political organization.”[13] Marseille’s census records adds to our understanding of the complexity of urban household gender hierarchy. Hardwick argues the assumptions connoted by “‘patriarchy’ veils the complexity, myriad actors, and multiple sites involved in creating and maintaining a cultural construction that would meet the needs of many different people.”[14] My work adds the interests, needs, and possibilities for spatial control of female heads of household.

Urban building units in Marseille provided working and living spaces four to five stories high where women and men of varied social ranks and professions lived together in varied household compositions. Despite cultural expectations of marriage and male dominance within households, recent scholarship underscores how married, widowed, divorced, and single women experienced various degrees of agency and autonomy. Scholars have also challenged the family economy model, where women’s work is considered supplemental to men’s work whether inside or outside the household. James B. Collins underscores how by the mid-eighteenth century more and more women appeared in rural and urban tax records— with a mix of married, widowed, and unmarried women directly responsible for taxes.[15] Nancy Locklin’s analysis of the city of Quimper’s 1748 tax rolls reveals the variety of marital and familial status of working women and household compositions that challenge assumptions about the traditional, patriarchal model.[16] Marseille’s revolutionary census and tax records reveal the continuation of a variety of opportunities for urban women from varied socioeconomic positions to control property and household space.

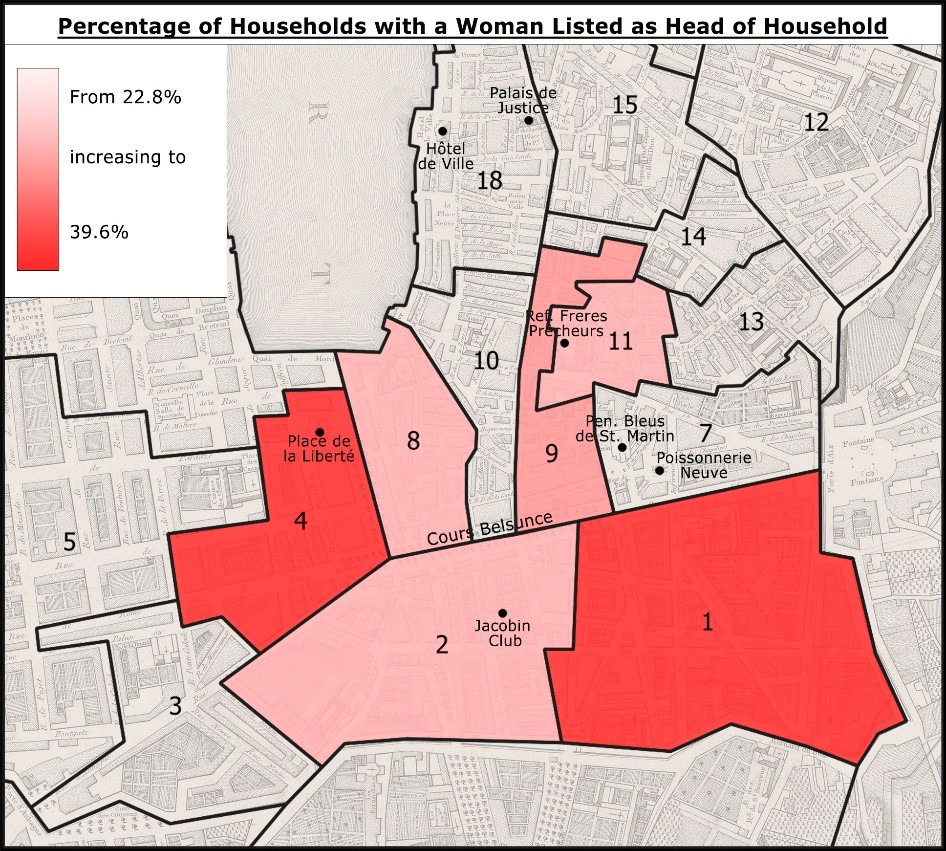

Figure 1: Percentage of Households with Women Listed as Head of Household[17](Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 1: Percentage of Households with Women Listed as Head of Household[17](Click here for interactive Section map)Women in Marseille headed a significant percentage (27.3 percent) of the 5,063 households across the six Sections surveyed between 1792 and 1793. Gehrman’s analysis of French and German census lists for 1846 and female-headed households compared rural census data. Like myself, he interrogates these records to understand the relationship between household compositions and female autonomy. French rural census data showed “the percentage of females as household heads was higher in France than in Germany (18.1 percent compared to 15.3 percent, or 18.1 percent as compared to 15.9 percent, if Altmütter [grandmothers] and Altväter [grandfathers] are considered as heads of their own household).” [18] A preliminary hypothesis is that women in urban environments experienced more opportunities for domestic authority outside of direct patriarchal control than women in rural environments, which matches the findings for German female heads of household in the nineteenth century. If we compare the percentages of female heads of household in revolutionary Marseille to those in mid-century rural France (27.3 percent versus 18.1 percent), female-headed households were 51 percent more prevalent in Marseille. I acknowledge there are a number of possible explanations for the results of the data collected to date. First, this is a preliminary study of an urban landscape based on census lists collected during revolutionary upheaval. Second, while there is overlap with Gehrman in counting for explicit and inferred head of households, there is a difference in my approach. I intentionally go beyond legal definitions of head of household to take into account the complexities of urban living in multi-dwelling living and work spaces that provided single women varied choices in employment and living arrangements.

However, the work of Locklin on eighteenth-century Brittany lends credence to my hypothesis. Over the course of the eighteenth century, tax rolls for towns and cities in Brittany show that between 14 to 30 percent of households were headed by women. In Brittany’s small towns, a significant percentage of rural households were headed by widows or women who never married (20 to 30 percent). Locklin further concluded that port cities “tended to have a higher percentage of female-headed households” due to the high number of men at sea.[19] Census records surveyed to date from revolutionary Marseille demonstrate a continuity in such eighteenth-century trends between northern and southern regions in France.

In Marseille, male married heads of household comprised only 41.8 percent of all heads of household compositions across the six Sections. This is interesting in and of itself, and supports Deborah Simonton’s work on widows and unmarried women’s agency in eighteenth-century European urban economies. According to Simonton, “[d]ecentering marriage and challenging assumptions about the marital couple as the norm helps to illuminate the ways towns operated as well as the variety in how women’s world of work operated.”[20] However, Marseille’s revolutionary census records have led me to conceptualize the category of singletons differently than Simonton in my analysis. While the census records allow me to delineate between married, widowed, and unmarried women, many women (and men) have no family status listed. While widowed or those identifying themselves as unmarried are by definition single, I broaden the analysis of singletons by including women who appear to be living on their own in a residence with no discernable family members, employer, or even a domestic servant. I identify singletons in the data analysis and mapping under the category of “living alone.” I define the category of "living alone" further for singleton female-headed households by excluding widows and unmarried women living with servants who had the financial means to hire the support of another individual as they navigated women’s possibilities and limitations in an urban environment. Thus, I am able to layer my analysis to consider those women making their way outside of family or hired help.

Thinking about singleton women living alone as head of their own households within residences nuances our understanding of women’s agency in an urban environment. As Simonton highlights, “singletons made up significant proportions of women and workers in towns and engaged in work across the economy, from the vigorous businesswomen to the charladies, servants, street sellers and prostitutes of commercial towns.”[21] Census records for revolutionary Marseille show the presence of singletons across the socioeconomic spectrum. Evidence from census records also suggests the notable presence of singletons cannot be attributed primarily to an exodus of men for revolutionary needs, and appears to indicate patterns that predate the Revolution.

Methodology for Qualifying Types of Female-Headed Households

Census records analyzed to date vary in their recordings of households, from tables listing individuals in households to the original individual sheets used to record households. Consequently, the headings and details in these records vary slightly between the six Sections analyzed. There does appear to be consistency overall in listing the assumed head of household first. For example, census records list husbands, then wives, then children, then domestics. However, occasionally census takers recorded a wife before the husband or the children. If records list the husband as absent, I have counted the wife as the de facto head of household. If the wife is listed before the husband, I have looked at how much information is provided that would indicate she is the one most responsible for the household. Usually this is only when the husband is listed as “at the frontier” or in the army as well as away on business or absent without any known reason why. There are very few women who fall in this category in my analysis. One exception is the case of Claire Amphous, aged sixty, who is listed before her husband. While her profession is listed as bourgeoise, her seventy-year-old husband’s physical status as a paralytic is listed instead, with their unmarried grown son and daughter following in the census. It is interesting that the son is listed as a commis (bank clerk), indicating that the mother likely controlled the most resources in the family.[22]

No questions arose for counting widows listed with underage children, but many widows lived with their adult children. When assessing whether or not to count such widows as the head of the household, I also looked for ordering in the census lists. Some census takers in their abbreviated records made all heads of households clear, listing only the head of household and the number of family members, such as Anne veuve Ripert and family of two, or veuve Vian and family of six in Section 1.[23] When the widow was listed before her grown children, with their own children following and domestics, I counted the widow as the head of household. Gehrman describes this problem of whether to count the widow separately from the family or not and lists both the widow and the first son as heads of household.[24] Following the pattern of ordering across the census records, when widows are listed after their grown children and grandchildren, I inferred that the widows were living in the households of their children rather than the grown children living in the household of their mother. Similarly, when aunts are listed first, they have been counted as the head of household even if there are grown nieces and nephews living in the unit. Aunts and uncles are also listed after nieces and nephews, which appears to indicate they have moved in with these family members. Adult siblings listed after married brothers and their wives and children are not listed as the head of their own household.

Other configurations give us men and women living together without the relationships being stated. If a woman and a man appeared in the register with no family status indications or professional ties, I had to look at the composition of the entire building – the multiple levels, and indications of which floor each individual, family, employees, or servants lived on. Further indications also reveal whether they occupied the whole floor, several rooms, or an individual room. When it was clear they shared a room, I counted the male as the head of household based on my own work on Marseille’s divorce records, which shows that prior to the legalization of divorce in 1792, women and men had de facto separations and lived with extramarital partners.[25] However, census records did not always give such level of detail. In these cases, I looked to see if there was a servant or a married couple or family listed after the woman based on other clear patterns in census records. For example, in the case of Jean Pierre Piscatory, bourgeois, aged sixty-nine, only two other people lived in the residence: Catherine Gracy, aged sixty-eight with no profession listed, and Elizabeth David, domestique, aged thirty.[26] I tried to err on the side of undercounting women as heads of households when the patterns of the data led me to believe the man and woman were a couple but not married. If a household listed groups of men and women living on the same floor but in separate rooms without any family or professional ties, and it was clear that the women headed their own household (even if merely a room), I counted them as singletons. If the same conditions existed but only the floor was indicated, I tended to count each individual of age as independent due to the patterns of the census tables that showed such unrelated individuals renting a single room in a residence.

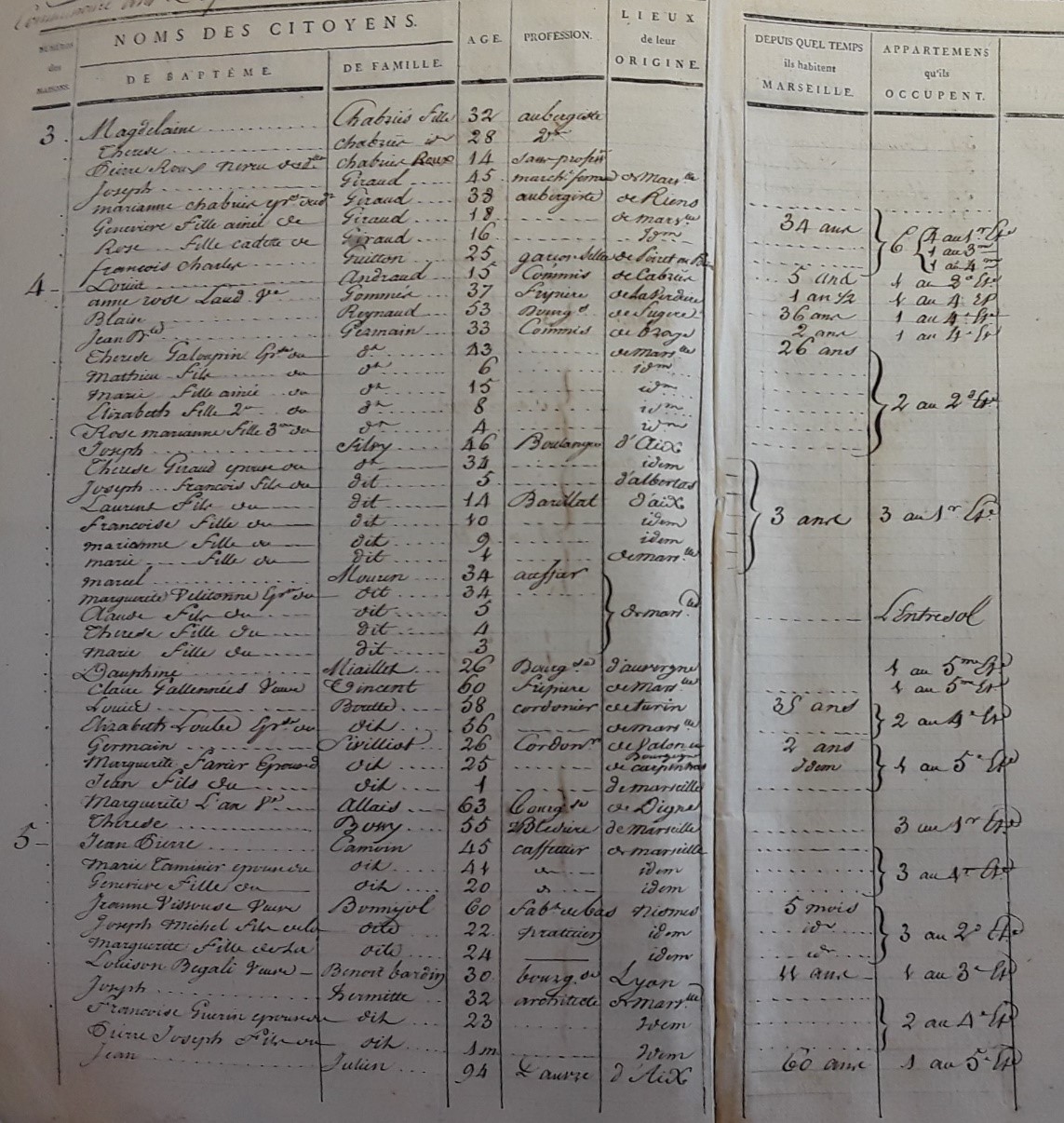

Figure 2: Section 2 Census Sample of Apartments/Floors OccupiedArchives municipales de Marseille, 2 F 2 Recensement juillet 1792

Figure 2: Section 2 Census Sample of Apartments/Floors OccupiedArchives municipales de Marseille, 2 F 2 Recensement juillet 1792When two women were listed as living together, whether they were related or unrelated, I counted each as independent, and thus their own head of household, if legally they were of adult age. In the same vein, when sisters and brothers of adult age were listed as living together without parents, husbands, or wives, I also counted each individually since under the law unmarried women of age were not under the authority of their brothers.

Marital, Familial, Socioeconomic, and Professional Status

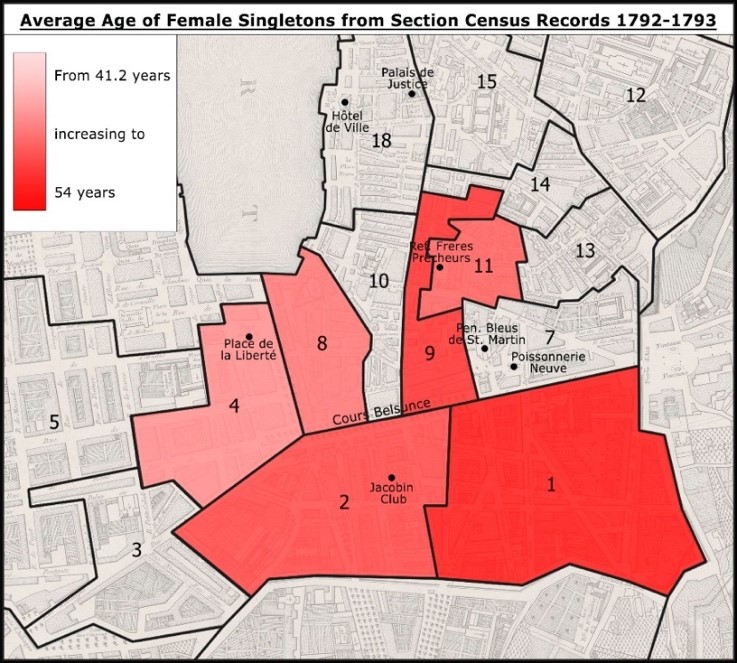

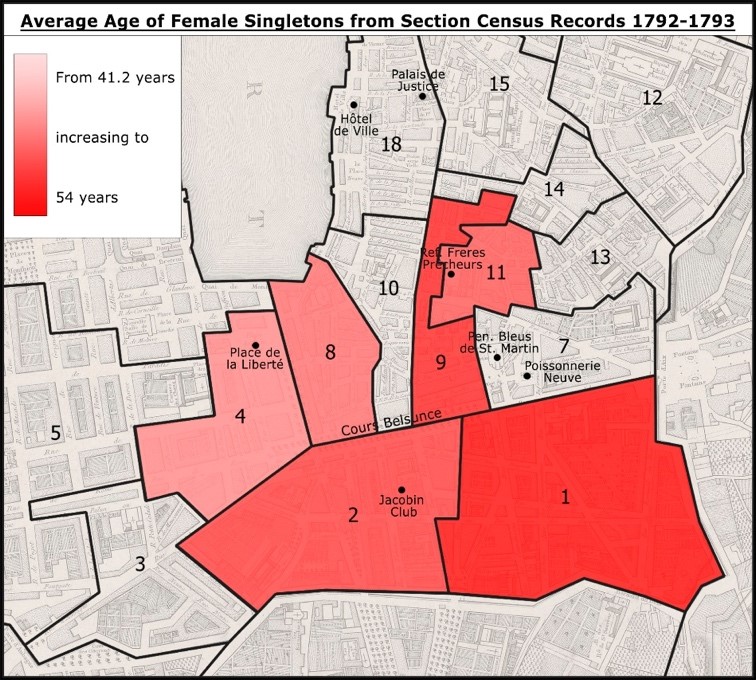

Marital, familial, socioeconomic status, and life stages created the conditions for female-headed households. Labor force conditions and female life stages shaped experiences and degrees of autonomy for women as heads of household in a patriarchal society. James B. Collins divides female life stages and women’s economic lives into three stages. In the first stage, many single women entered the work force at age fifteen as day laborers, textile workers, and servants.[27] Urban environments provided opportunities to earn wages, often needed to save for a dowry. In Marseille, young women in this first stage of economic life were less likely to be female heads of household. The average age of all females in the six Sections ranged from thirty to thirty-five years of age. But the average age of singletons across the six Sections ranged from forty-one to fifty-four years of age.

Figure 4: Average Age of Female Singletons from Section Census Records 1792-1793(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 4: Average Age of Female Singletons from Section Census Records 1792-1793(Click here for interactive Section map)Marriage and childbearing years between ages twenty-five and forty typically dominated the second stage of women’s economic lives. Collins notes the range of married women’s contributions in urban households, with their income ranging “from the very low wages of a spinner or unskilled laborer (although in towns these were usually the occupations of single women) through the modest contribution of the revendeuse [reseller] and all the way up to the substantial income of the independent business woman: tavern keeper, grain broker, linen merchant,” etc.[28] Locklin’s analysis of married females in the Quimper guilds shows the complexity of assumptions about the patriarchal household as the norm, noting that women “admitted as mistresses in the trade on their own merits kept their individual status in the guild when they married, as long as they married men” not in the same trade.[29] Recent studies for early modern Sweden, based in part on eighteenth-century urban trade, use the concept of the two-supporter model within the marital economy that “created a position of status and power for both spouses” who “made their own decisions and controlled their day-to-day work” despite the unequal status of women.[30]

Widowhood comprised the third common stage of a woman’s economic life. Simonton notes that “[t]he single woman and the widow, despite neither having a presiding male around, were not treated or perceived the same. Their difference was often as important as the apparent similarities, since laws, customs and economic structures often appeared to benefit widows while either ignoring or specifically excluding single women.”[31] Widowhood did not, according to Locklin, “necessarily bring about drastic changes in a woman’s work life,” especially if she continued in “an established trade of her own or a shared family business.”[32] Admittedly, they often relied on adult male help, either from a son close to or of legal age, or a married daughter and son-in-law, to help run the family business or manage properties and the income they yielded. Widows continued to employ and hire male workers as necessary for the enterprise at hand, wielding as much authority or more than they did when married.[33] Widows from more precarious socioeconomic ranks were more vulnerable and many ended up on parish charity rolls. However, others functioned successfully in the same ways that unmarried singletons did by sharing household costs with a roommate or sibling.[34]

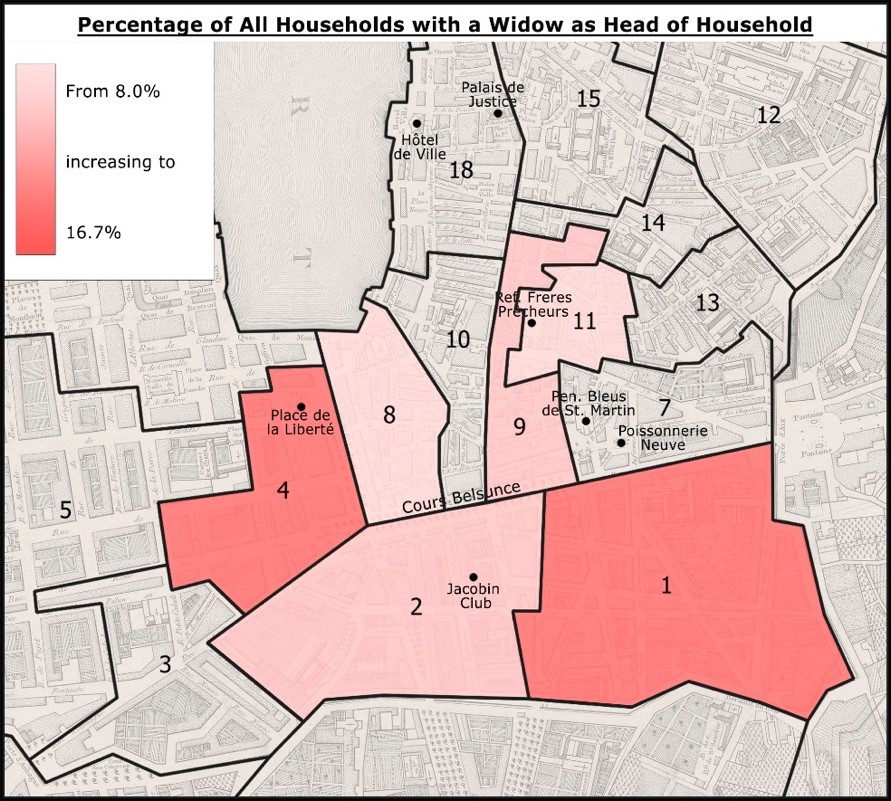

Figure 5: Percentage of All Households with a Widow as Head of Household(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 5: Percentage of All Households with a Widow as Head of Household(Click here for interactive Section map)Without combining unmarried women and females with no marital status listed, widows in Marseille comprise the largest percentage of female-headed households. In the six Sections surveyed, widows comprise from 35.2 percent to 42.7 percent of female heads of households, while widows headed 10.7 percent of all households. The percentage of widows as heads of households relative to all households was highest in Sections 1 and 4 (16.2 percent and 16.7 percent respectively). This stands in contrast to male-headed households, where, in Marseille, widowers were the least likely males to head households (less than 1 percent). Widowers, it appears, were more likely to remarry, whereas widows may have preferred not to remarry if they had sufficient social and fiscal capital, yielding increased agency, and autonomy as heads of household. Widows may also have had a harder time remarrying if they were past childbearing years and/or had few resources to offer a prospective husband.

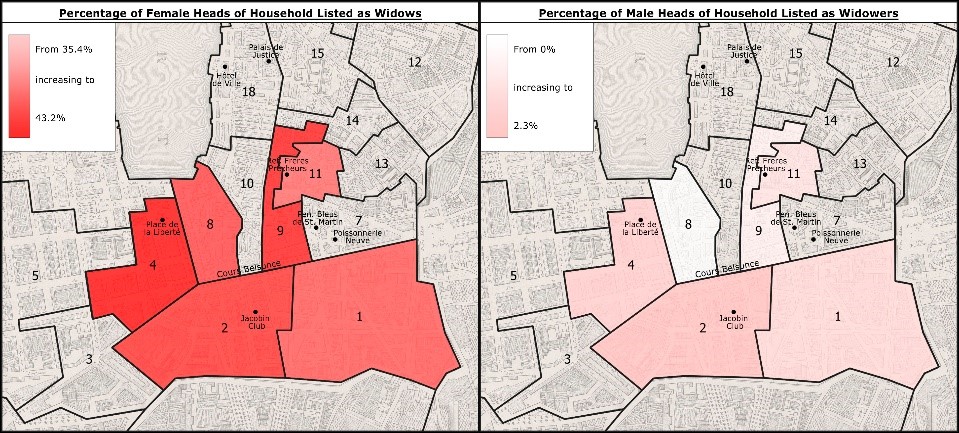

Figure 6: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Widows v. Percentage of Male Heads of Household Listed as Widowers(Click here for interactive Section maps)

Figure 6: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Widows v. Percentage of Male Heads of Household Listed as Widowers(Click here for interactive Section maps)The average age of widows is consistent across the six Sections. Census data for the Sections reveals relative homogeneity for the average age of head of household widows (thirty to thirty-three years old) in comparison to the average age of the overall female population (thirty years old) in these Sections. Considering the average age across the Sections, many widows appear to be just past their prime childbearing years but theoretically still able to conceive for several years.

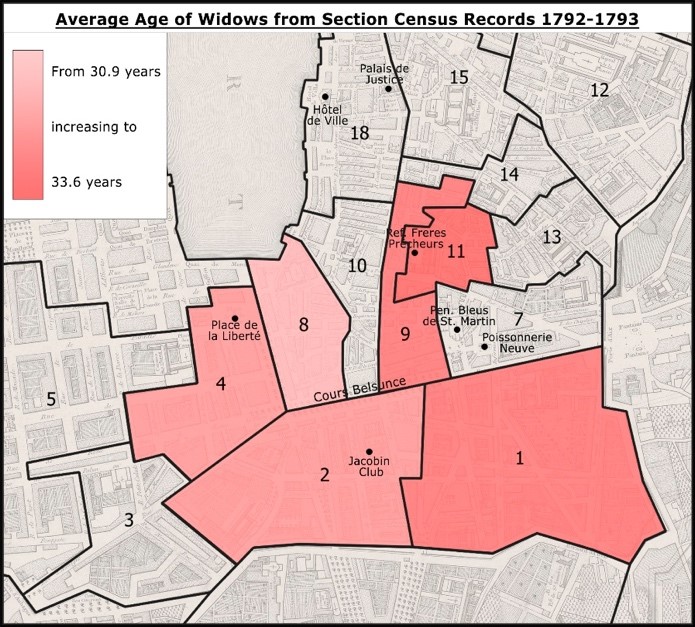

Figure 7: Average Age of Widows from Section Census Records 1792-1793 (Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 7: Average Age of Widows from Section Census Records 1792-1793 (Click here for interactive Section map)The average age of widowed singletons in Section 4, for example, was thirty-two years. Widowed artisans in Section 4 were also on average thirty-two years old, as were bourgeois widows. The evidence suggests that widows in Marseille’s urban spaces often found themselves widowed relatively young. Geospatially, it wasn’t only widows in the wealthier areas who did not remarry, but also those in poorer areas with enough resources to manage their affairs without having remarried in their early thirties, who were thus able to take advantage of the opportunities that being the head of the household provided. The highest percentage of widows living alone was in Sections 11, 4, and 9, at 40 percent, 39 percent, and 33.3 percent respectively. Overall, 27.5 percent widowed females heading households lived alone, and those in the vastly poorer Sections of 11 and 9 likely struggled more to survive. But under-resourced widows living alone likely found socioeconomic networks in residences with other singletons, enhancing widows’ degrees of agency and autonomy.

The analysis of professions and lifecycle stages for widows is overall incomplete since the census data does not note professions for many women. For example, Sections 11, 9, 8, and 1 listed no professions for 70.7 percent, 69.4 percent, 52.9 percent, and 50 percent respectively of widow-headed households. Section 4 and 2 provide the exceptions, where only 9.8 percent and 2 6percent widow-headed households did not indicate a profession. Section 4 bordered the side of the Canebière with the city’s newer quarters. Small business owners, artists, and artisans lived and operated here, and served a wealthy clientele. Section 2, near the Cours Belsunce and the Canebière, was “comprised of some of the most fashionable streets and residences in the city, home of some of the wealthiest merchants.”[35] Although these two areas had more wealth, Section 1 also housed a wealthy population, which perhaps indicates a reporting bias in Section 4 and 2 that favored recording the professions of as many members of the residence as possible.

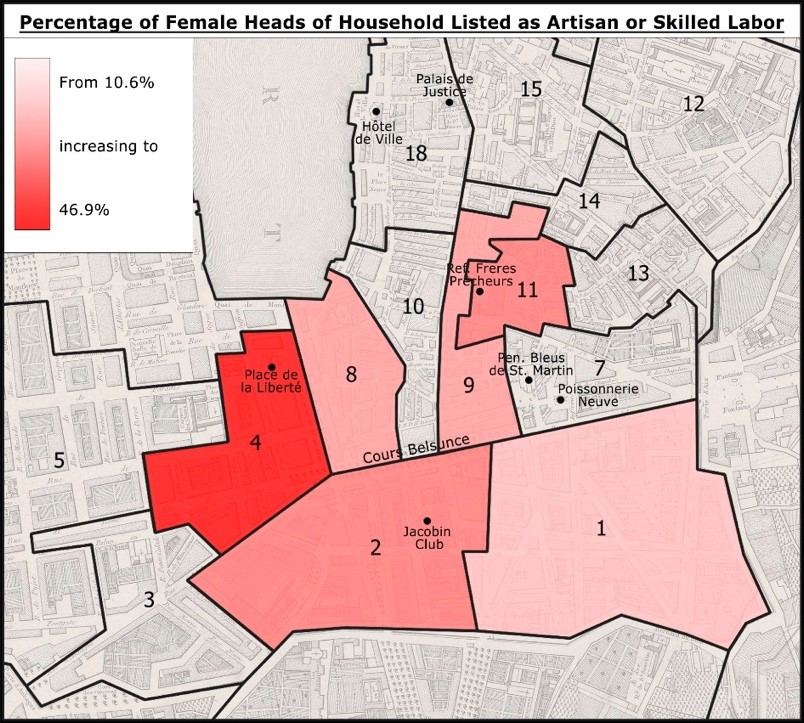

The percentage of bourgeois, artisanal, and skilled laborer heads of household widows varies considerably across the six Sections, but the percentage of widows’ professions corresponds for the most part with the known socioeconomic compositions of these areas. For example, evidence reveals that Section 4 had the most widows as heads of households, comprising 42.7 percent of its total female heads of household. Section 4 also had the highest percentage of artisanal and skilled laborers as female heads of household (46.9 percent), which correlates with the socioeconomic composition of the Section. Data from Sections 2 and 1 show bourgeois widows as 35 percent and 30.8 percent of the respective widow-headed households, which is consistent with overall professional trends for female heads of households in these two Sections.

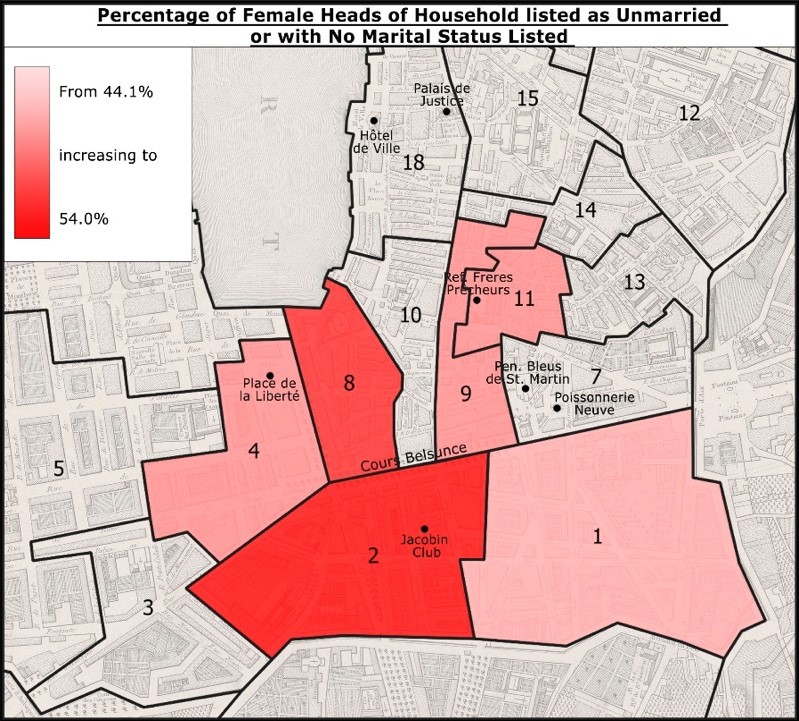

Figure 9: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Unmarried or with No Marital Status Listed(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 9: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Unmarried or with No Marital Status Listed(Click here for interactive Section map)Overall—and consistent with other studies—of the women in Marseille who identified their marital status, widows were the most common female heads of household (39.2 percent). However, when numbers are taken together for those female heads of household listed as unmarried women and no marital status listed (668)—who were also likely single—they form the highest percentage of female-headed households (48.5 percent), and the Section percentages range from 44.1 percent to 54 percent. Sections 2 and 8 both had over 50 percent of female heads of household in the unmarried/no marital status category, and Section 9 and 11 had just over 46 percent of female-headed households in this category. Socioeconomics is not enough to explain this trend since the range of Sections represent the high and low ends of the socioeconomic spectrum in Marseille. Section 2, for example, housed some of Marseille’s wealthiest merchants and was located near the famed tree-lined streets of the Cours Belsunce and the Canebière. And although only 6.4 percent of women and men in Section 2 are identified as bourgeois (258 women and men out of 4031 individuals counted in the census), 32.2 percent represented bourgeois female heads of household. Section 8 housed many more female head of household artisans and workers overall (sixty-one) with only fourteen women and twenty-four individuals overall identified as bourgeois out of 1,095 professions identified and a census population of 2,679.[36] In Section 9, “one of the poorest” of the old town,” female and male artisans and skilled workers combined occupied over 50 percent (591) of the 1,028 identified professions, and 21.9 percent of female-headed households were artisans or skilled laborers. Section 11, which shared similar overall populations, had 27 percent of female-headed households led by artisans or skilled laborers.

That unmarried women and those without a known marital status with means headed so many households is perhaps less surprising. But unmarried women of much lesser means are usually assumed to be living in destitute conditions, and that certainly is the case for some women identified in the census as dependent upon charity. Unmarried day workers could be assumed to occupy a marginal socioeconomic status with the vagaries of day-to-day employment. Yet women on the margins, as increasingly borne out by studies, led complex and enterprising lives. A case in point is Marie Caviran from Section 9, who identified herself as a day worker. Her eighteen-year-old son (listed after her in the census) worked as an artisan who made objects from gold (or silver).[37] No husband is listed, and the only other person living in the household was an aged male domestic, “Le Vieux Louis.” Assessments of never married women’s agency increasingly shows that women in this category may have delayed marriage because of good wages and opportunities, or they chose to live with other women in the same profession to cut living expenses and maximize socioeconomic networks, or they may have chosen to never marry, preferring to live women-centered lives.[38] Further, among those who did not list their marital status, some were living in household compositions that went against the norms Hannah Callaway cites of young unmarried women living with their families. For example, in Section 8, thirty-year-old Marie Arnoux lived in a mixed household with three different married couples and their families living on the first through third floors. Arnoux, a tailor (tailleuse), however, lived on the fourth floor alongside two other men. Census records indicate each had their own room. She was the only tailor living in the building.[39] My impression is that this was not uncommon.

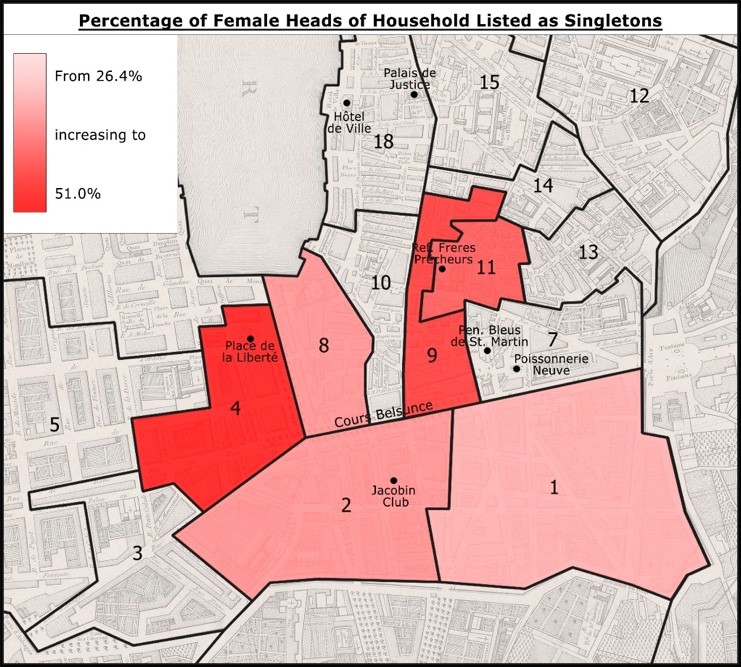

Figure 10: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Singletons(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 10: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Singletons(Click here for interactive Section map)Female singletons (defined as heads of their household by virtue of living alone—whether renting a single room, an entire floor, or leasing out rooms), comprise the third largest percentage (36 percent) of female-headed households surveyed. The average age of female singletons was forty-seven years. Each Section shows a consistent pattern of average ages in the forties and fifties for women living alone, outside of marriage, outside of family structures, and outside of their workplace.

Figure 11: Average Age of Female Singletons from Section Census Records 1792-1793(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 11: Average Age of Female Singletons from Section Census Records 1792-1793(Click here for interactive Section map)However, averages belie the fact that women as young as fourteen and up through their early twenties also lived as singletons in Marseille. Hardwick’s most recent work, Sex in an Old Regime City, analyzes the nearby urban center of Lyon and the latitude for public and private displays of affection and intimacy for young adults in these years, noting:

the transition phase of emerging adulthood was characterized by a decade or more of work and play as singles between their first jobs in their teens and their marriages in their mid/late twenties. The multi-purpose streets and buildings of the city where they lived had much in common with other parts of pre-modern Europe. The streets were public spaces that were at once commercial, social, productive, functional, and emotional as well as sites of religious observation, revelry, and intimacy.[40]

Magdeleine Lange, age fourteen and born in Marseille, worked as a blanchisseuse (a laundress) and lived as a singleton in a building with a socioeconomic mix of thirty-nine other residents: a female clothes designer living with her parents and siblings; a hair stylist and his family; an academician and his sister; a bourgeois widow and her grown children; a cook and his wife who ran a boutique; and other singletons, including a widow with no occupation indicated, and two female singletons listed as female butchers.[41] Census records illustrate the complexity of interior spaces and the varied household and production arrangements. Hardwick brings life to these spaces in her explanation of how “buildings that fronted on the streets masked complex interior space where public and personal, domestic and commercial were interwoven in shared rooms, courtyards, staircases, and balconies. People, activities, and goods circulated between households that were very porous. The households were sites of production and credit/debt production as well as residential spaces.”[42] Although Magdelaine did not live with any relatives, she would have still been caught up in complex household dynamics, where “[b]oth co-operation and friction about a wide range of issues profoundly shaped relations between and within households, and power relations along many axes were integral parts of inter- and intra-household life.”[43] Her actions within the household, who she entertained and where, whether in the streets, courtyards, and doorways where licit and illicit forms intimacy occurred would have been subject to oversight by residents in the building, by neighbors, and members of the workplace. Young women and men had considerable breadth in terms of licit public intimacy as long as it appeared within the framework of suitable partners for marriage. In fact, workplaces provided ideal spaces for many young women and men to find suitable partners.[44]

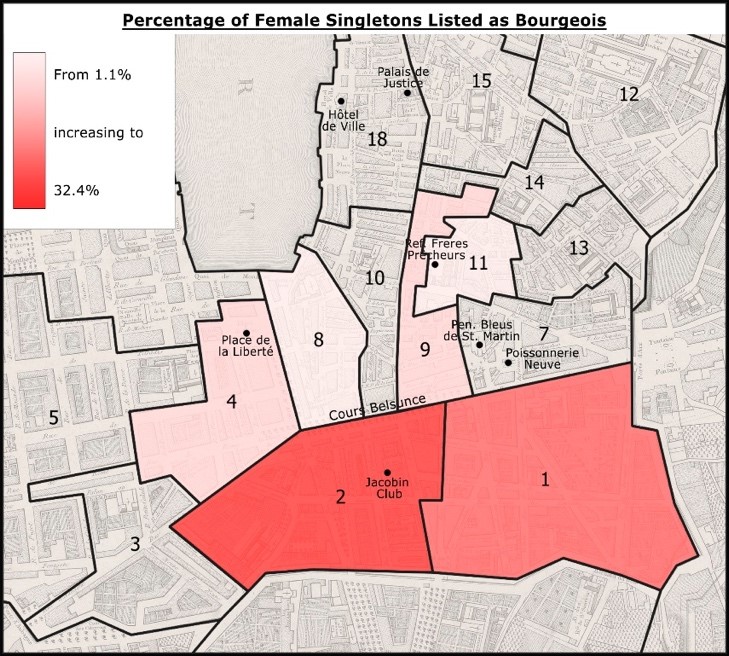

So what were the socioeconomic conditions of the singletons surveyed in Marseille? Bourgeois, artisans, and skilled laborers dominated. Of all female singletons, Sections 1 and 2 had highest percentage of bourgeois singletons at 23.9 percent and 32.4 percent respectively. The elite status of these women did not necessarily allow them more freedom of movement in the city and opportunities for intimacy than women from lesser socioeconomic ranks since social capital was directly tied to individual and family honor.

Figure 12: Percentage of Female Singletons Listed as Bourgeois(Click here for interactive Section map)

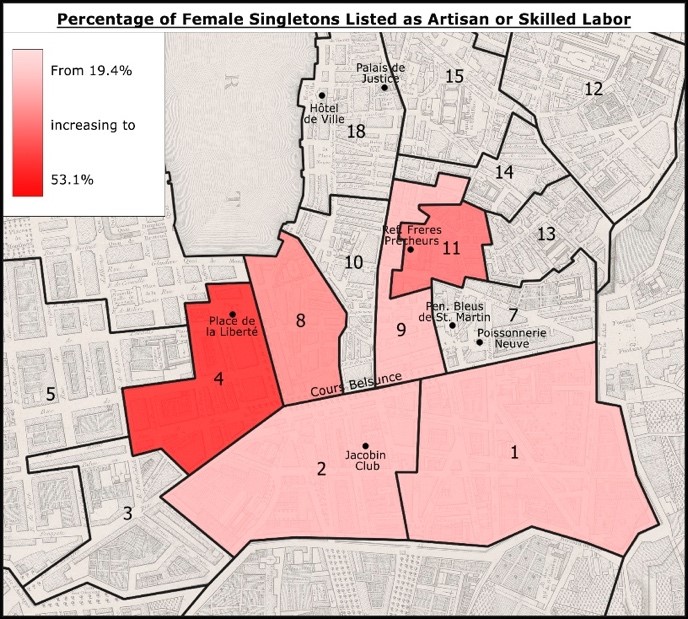

Figure 12: Percentage of Female Singletons Listed as Bourgeois(Click here for interactive Section map)Hardwick notes that the workplace provided women and men the opportunity to meet and spend time together and ultimately choose their intimate and potential marriage partners.[45] Those in artisanal and manufacturing trades, such as the majority of female singletons in Sections 4, 11, and 8 (53.1 percent, 34.1 percent, and 30.6 percent respectively), would meet those of similar age, skills, and experiences. Despite their enhanced autonomy over those of bourgeois singletons, female artisans and skilled laborers still had reputations to risk, and would be subject to the scrutiny of their employers, workmates, and neighbors. But for some, reputation could not trump economic survival, such as Marie Jeauffroy and Marie Imbert in Section 4, identified their profession by the colloquial phrase fille d’amour (a euphemism for prostitute), which is not common across the six Sections surveyed.[46] Fille d’amour may be more frequently used in Sections not surveyed, where prostitution may have been localized.

Figure 13: Percentage of Female Singletons Listed as Artisan or Skilled Labor(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 13: Percentage of Female Singletons Listed as Artisan or Skilled Labor(Click here for interactive Section map)Across the six Sections, few households were listed with adult sisters and brothers or solely adult sisters living together who had no marital status ascribed. Yet such households bring up the question how much individual autonomy was enhanced for women when siblings cohabitated. Was it less for women living with brothers and more when living with sisters? Likely adult sibling households found it the best strategy for conserving familial property and resources. For example in Section 8, Genevieve Bosq, aged fifty-six, lived with her brother André Bosq, a cotton merchant, aged fifty-one. No profession is listed for her, and no one else lived in the residence. While she is legally independent, they may have shared the household in an economic arrangement where she functioned much as a wife would to support the household and the family business.[47] Although I counted Marie Claire Rose Boisselié, aged forty-seven, and her brother, Thomas Boisselié, aged forty-six, each as a head of household in Section 2, it is likely that her brother would have disagreed. He lived on the first floor, and she lived on the second floor with their three domestic servants. His profession is listed as négoçiant (merchant trader), but under her profession is the statement that Thomas took care of his sister. Under the category “Observations,” the census taker noted: “sieur Boisselié stated that he incessantly tended to the needs of his [sister] occupying the second floor of his house.”[48]

Sister-sister partnerships may have been more empowering. The Rousset sisters, Marie, aged forty-seven, and her significantly younger sister Augustine, aged thirty-six, also lived in Section 8. Their socio-economic circumstances do not appear as comfortable as sieur Boisselié and his sister. Marie was listed as an emery merchant, which may have encompassed the work of the two sisters together. Their means for supporting a household put them in a larger residence with ten other neighbors in the building, and it is not clear whether they occupied a floor to themselves or merely a room or two. Others like Claire Brignolle, aged thirty, held the status of principal lessee and lived with Annette Brignolle, aged twenty-seven, in Section 2. The sisters likely worked together in terms of renting out rooms to three men (a bank clerk, a bourgeois, and a commercial agent) and one woman (no profession listed), as well as hiring a male domestic worker. The choice of a male domestic may indicate the women needed additional male strength for household upkeep and perhaps even to give the sense of male protection in the household, considering they seemed to rent primarily to unmarried men.[49] Locklin’s research in Brittany reveals how females, including siblings, could create a legally binding “perpetual society” and “designate one another as primary heir...to protect their community property from the claims of others” under Brittany’s customary code of 1725.[50] Such partnerships could protect both large and small amounts of community property and possessions. It would be interesting to know if sisters living together as well as other single women sharing a household could make similar arrangements under Roman law.

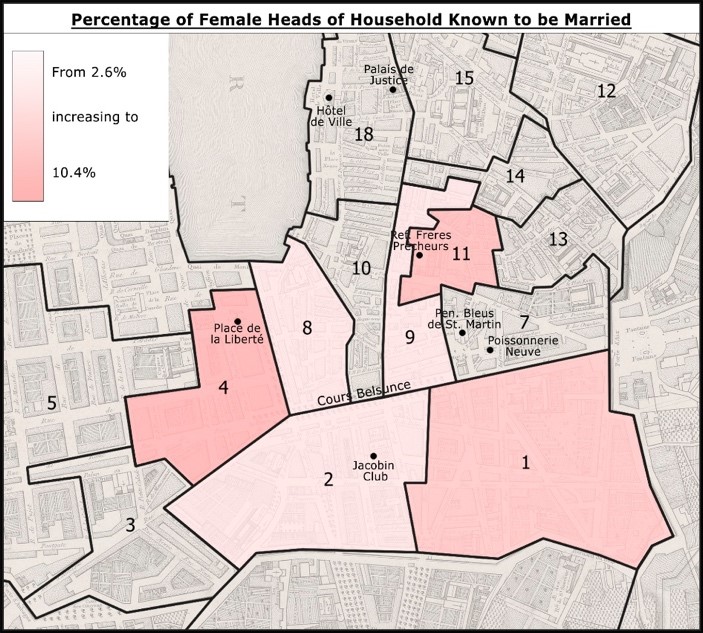

Figure 14: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Known to be Married(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 14: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Known to be Married(Click here for interactive Section map)Married female-headed households are the lowest percentage (5 percent) of all female-headed households in the Sections surveyed. Percentages for married female heads of household range from 2.6 percent to 10.4 percent across the Sections. Questions do arise when comparing Sections. For example, Section 4 shows 10.4 percent of female heads of household as being married, and in both Sections 1 and 11 married women accounted for 7.5 percent of the female headed households. A socioeconomic analysis of women’s livelihood does not necessarily explain why some Sections had higher percentages of married women heading households than other Sections. For example, Section 1 and 2 had the highest percentages of bourgeois-headed households (26 percent and 32.2 percent respectively), but Section 2 had the lowest percentage of married female-headed households. In the case of female artisans and skilled workers, socioeconomic trends do correspond. Sections 4 and 11 had the highest percentages of female artisan and skilled workers as heads of household (46.9 percent and 24.9 percent respectively). In all cases, the socioeconomic categories point to higher levels of income for these women albeit at different levels. So what accounts for the difference? Perhaps women in Sections 4 and 8 had husbands in occupations related to the port economy that took them away from home regularly, leaving the women alone to run the household. Locklin’s study of Brittany revealed more women in port cities heading households for this reason.

Married, female-headed households bring up a number of questions related to revolutionary changes. Did these women leave their husbands or were they left by their husbands? Only rarely is a legal separation mentioned, such as in Section 2, with only two women citing separation and one woman citing abandonment. My own work on divorce reveals that while only 5 percent of the 246 divorces in Marseille between 1792 and 1794 were based on previous separations, 46 percent of women and 24 percent of men filing for divorce based their petition on abandonment, underscoring the existence of many de facto separations. Many other women likely never filed for divorce if existing living and economic arrangements worked well. France’s revolutionary war from the spring of 1792 impacted many families, as Alan Forrest has shown through his analysis of soldiers’ correspondence with their families.[51] I therefore expected to find many examples of married women temporarily heading households because of the war. However, in the six Sections surveyed only sixteen of the married women cited the war as the reason for their husbands’ absence. Expansion of the analysis of Marseille’s census records may show a disproportionate socioeconomic impact for married women in other Sections from poorer levels of society.

Figure 15: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Bourgeois or Merchant(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 15: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Bourgeois or Merchant(Click here for interactive Section map) Figure 16: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Artisan or Skilled Labor(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 16: Percentage of Female Heads of Household Listed as Artisan or Skilled Labor(Click here for interactive Section map)In terms of the socioeconomic conditions in Marseille, some trends emerge. Female artisans and those in the skilled trades appear to have had as much or more opportunity than bourgeois and merchant women for increased domestic authority and autonomy outside of direct patriarchal control. At 29.5 percent of female-headed households controlled by bourgeois or merchant women compared to those headed by female artisans or skilled laborers (20.8 percent), it might not seem that the latter women had increased opportunities for social and economic independence. While Section 2 and 1 had the highest percentages of combined bourgeois and merchant female heads of household (37.2 percent and 27.2 percent respectively), nearby Section 4, on the side of the Canebière with the new quarters and home to artisans and skilled laborers, had an even higher percentage of artisan and skilled laborer female-headed households (46.9 percent). The wealth of all three Sections clearly made a difference, and Section 2 had the third highest percentage artisan and skilled laborer female-headed households (23.6 percent). As noted early, however, female artisans and skilled laborers in Section 9, one of the poorest areas with undoubtedly cheaper rental housing, had the second highest percentage of female artisan and skilled laborer heads of household (21.9 percent). Section 11, which shared similar overall populations, had 27 percent of female artisans and skilled laborers heading households. But female-headed households by artisans and skilled workers in Sections 4 and 2 may have experienced higher levels of economic stability than their counterparts in Sections 9 and 11 by virtue of their proximity to bourgeois and merchant clientele.

Female Heads of Household as Primary Lessees and Property Owners

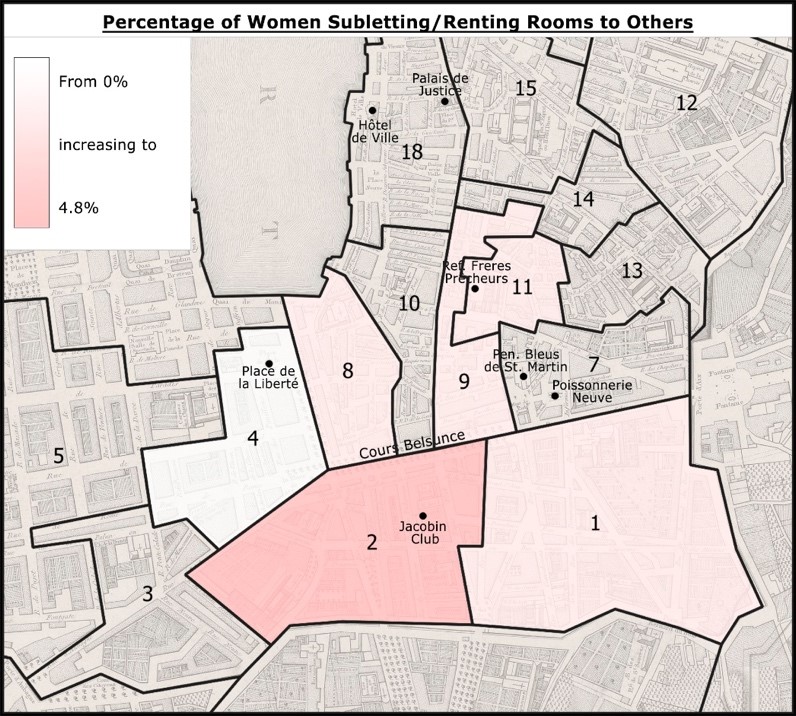

Hannah Callaway’s work on Parisian urban renters and landlords during the Revolution analyzes how a “burgeoning real estate market created opportunities for investment” and changed social relationships.[52] From the small sample of tax records and significant-sized census records analyzed, women in Marseille took advantage of opportunities to rent out their urban property while living on and off the property. Women also controlled property as primary lessees and used subletting whole floors and individual rooms to secure their finances. However, this was not common. In Sections 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, and 11, only twenty-two women indicated income from renting rooms, whether as principal lessees, boarding house, or inn operators, with 68.2 percent of these women in Section 2. Owner Magdelaine Giraud veuve Besson in Section 2 occupied part of her home and rented out the remaining rooms and a ground-level store.[53] Magdelaine Cruvel, also in Section 2, indicated that the entire house was under her control and that she rented out furnished rooms. Cruvel catered to eight male renters some of whom had only recently come to Marseille. Marie Combe from Section 11 provided furnished rooms to four male foreigners.[54].However, the work of running an inn necessitated family or hired help. In Section 11, for example, Marie Angelique Legrand rented out rooms to twenty unidentified pensioners, assisted by her niece and two unnamed domestics. More men with families were innkeepers than women.

Figure 17: Percentage of Women Subletting/Renting Rooms to Others(Click here for interactive Section map)

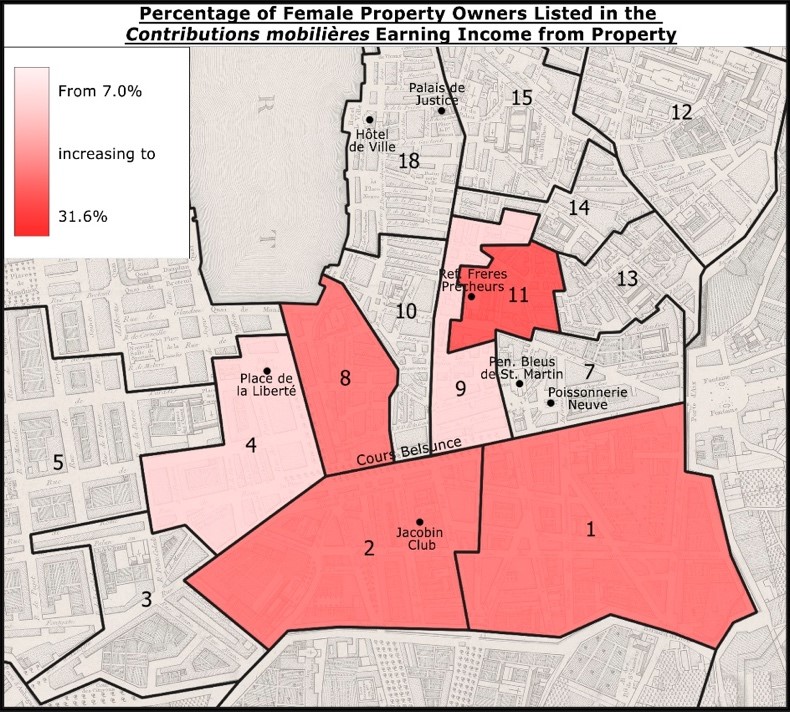

Figure 17: Percentage of Women Subletting/Renting Rooms to Others(Click here for interactive Section map)Calculations for female property owners come from the required contributions mobilières for income earned by rent or industry and from the census records, which sometimes identify the owner of the building and generally indicate relatively equal percentages of women to men identified as bourgeois. Adding the category of bourgeois helps identify women’s relationship to property in terms of the economic ability to live off income from property or investments. As noted earlier, contributions mobilières discovered to date for Marseille are sparse, and combined with information from the six Section census records only allow identification of 696 property owners, including those identified as bourgeois. Women held nearly as much of that property as men (47.4 percent), but the result must be qualified. Men are more often identified in the census as owners than women, but most entries do not identify the building owner. In contrast, figures from the contributions mobilières, show a low percentage of female property owners earning rents or income: from 7 percent to 31.6 percent and only 17.3 percent of the total amount of property.

Figure 18: Percentage of Female Property Owners Listed in the Contributions mobilières Earning Income from Property(Click here for interactive Section map)

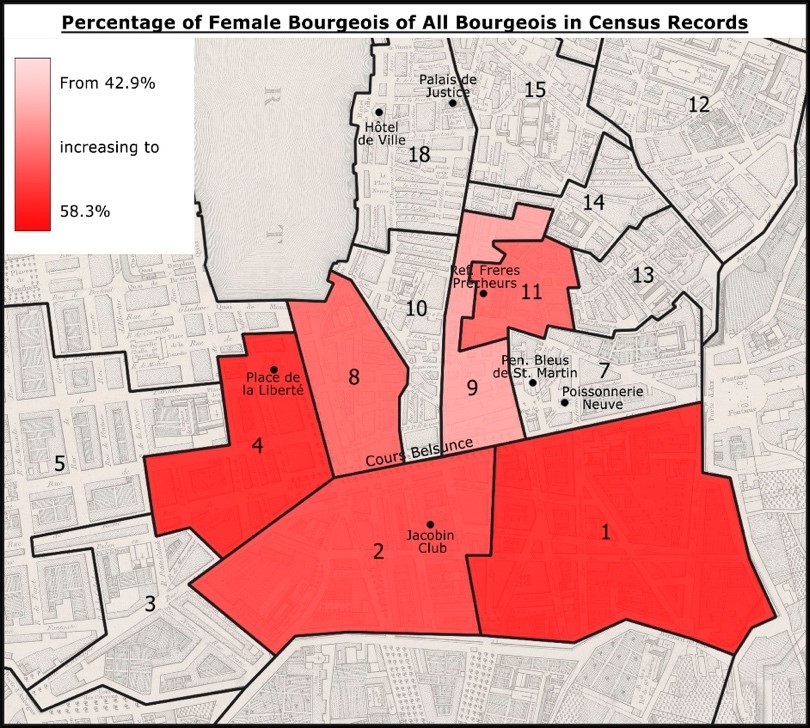

Figure 18: Percentage of Female Property Owners Listed in the Contributions mobilières Earning Income from Property(Click here for interactive Section map)Census records and the identification of bourgeois women and men reveal significant trends across the six Sections regardless of the socio-economic differences between the populations. Notice that in wealthier Sections 1, 2, and 4, the percentage of female bourgeois is higher than male bourgeois (56.3 percent, 53.5 percent, and 58.3 percent respectively), but even in other Sections women are 40 to 50 percent of all bourgeois identified. A bourgeois woman was likely to head her own household, with 72.5 percent to 100 percent of bourgeois women as heads of household. Combined, Sections 1 and 2 had the most women identifying as bourgeois and had the most bourgeois singletons (23.9 percent and 32.8 percent respectively). A bourgeois singleton could count on the income from their rural and urban lands or other investments without the explicit economic need to marry.

Figure 19: Percentage of Female Bourgeois of All Bourgeois in Census Records(Click here for interactive Section map)

Figure 19: Percentage of Female Bourgeois of All Bourgeois in Census Records(Click here for interactive Section map)Widows, especially bourgeois widows, made up a high percentage of female property owners. Of all female bourgeois, 34.7 percent identified as widows across the six Sections. Sections 1 and 9, despite being opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, had the highest percentage of bourgeois widows (44.4 percent and 40 percent respectively), and the highest percentages of widows as property owners (45.6 percent and 45.8). And widows were recorded more as property owners than widowers, but as noted earlier the low percentages of widowers as heads of households suggest they were more likely to remarry than widows. Some widows could count on sizable profits from their property. For example in Section 2, Dame Magdelaine Caune, veuve Demassue, who identified herself as bourgeois, listed her property as bringing in 2431 livres annually. With the lowest annual rent earnings at thirty livres and the highest at 5000 livres in the 170 contributions mobilières, Dame Canne earned the second highest amount of any man or woman in the six Sections analyzed to date. The highest reported rental income of 5000 livres was from the estate of the late Anne Thérèse Belleville, veuve Garroutte bourgeoise, also situated in Section 2.[55] Both women controlled property in the fashionable streets of the rue de Rome and the rue de Paradis.

Women from a surprising range of socio-economic levels owned, profited, and experienced increased authority from their property. The highest percentage of females owning property was in Section 11 (60.6 percent), part of the small area of the old town comprised of Sections 9-19 that housed nearly half the population of the city with its roughly 49,973 individuals.[56] Female artisans and skilled workers, who outnumbered bourgeois female heads of household in poorer Section 11, owned property. Marie and Marianne Blanc, for instance, were box makers. They appear to be sisters, one unmarried and the other married. Marie signed their contribution mobilière, noting rental income of 200 livres, plus an additional 150 livres of income from her workshops and stores.[57] The document reveals Marie and Marianne Blanc’s levels of authority: control over property, those who leased the property, the workshops and storefronts, and associated employees. Anne Rose veuve Pourquier in Section 8, a day worker who did not know how to sign her name, earned 366 livres annually from her property.[58] Interestingly, this was more than Claire Ricord veuve Monier in the same Section, who identified as bourgeois and earned rental income from the first level of a house and a boutique.[59] Other Section census records will reveal more women who owned diverse assets, like the widow Bouze and her son, millers by trade, who owned property outside the Port du Rome in Section 21. They reported some of the highest income from both their rental property income of 300 livres and the 8300 livres per year from “the rent of the mills that serve our industry.”[60]

Conclusion

More research is needed to analyze how much patterns in Marseille overlap and differ from Callaway’s findings. From the limited survey here, the six Sections mirror aspects of Parisian heterogeneous household compositions but also leave unanswered questions. Surprisingly in a period of the Revolution needing more and more soldiers, the majority of married women heading households did not cite husbands away in the army nor abandonment by their husbands. In most cases, it is not clear why these married women found themselves heading households. The few women noting absent husbands or husbands away on business became temporary heads of household, which may have been a reoccurring status as in other port cities.

Widows, married and unmarried women, and mothers without the mention of husbands found themselves as head of families in a period of time where patriarchal authority came under question in family laws that allowed divorce for the first time and which established increasingly egalitarian inheritance laws. How many of these women in Marseille benefited from these laws needs to be determined. Although more qualitative sources are needed to analyze what the census data reveals, the data already gives us more evidence that women living without the direct supervision of family and/or employers can be found across six very different and widespread socioeconomic areas of revolutionary Marseille. To what levels their existence undermined patriarchal norms and shifted domestic authority to women outside of marriage, whether as widows or unmarried women, needs more contextualization. Inheritance, divorce, and police records need to be investigated to bring to light more of the qualitative meaning of the data presented. Opportunities for unmarried women also must be better contextualized. Future studies could combine pre-revolutionary tax roll data to track bourgeois and other women who identified themselves as never married (fille) and also served as head of household to assess levels of continuity and change for female-headed households.[61] A comparison of female to male singletons that considers age and lifecycle is also needed.

In terms of the agency afforded by income from property, the records surveyed make clear that women could benefit as much or more from owning property than men. Analysis of the contributions foncières (land taxes), which assessed the rents and income derived from rural lands, another revolutionary tax, will expand our understanding of women’s control of property and domestic authority. Aligning notary records with census records will also reveal more female property owners since Marseille came under Roman law, which allowed married and unmarried women to inherit property even before the revolutionary changes in inheritance laws between 1791 and 1793. For the eighteenth century, Collins found that “[s]ome widows in the customary law regions, particularly Brittany and Anjou, made out fairly well, [while] those in Roman law regions were less well off.”[62] More research on widows in the early modern period in Marseille and the region of Provence under Roman law will allow for a more developed comparison to common law regions.

My focus has been mainly on household compositions and women’s control of interior spaces whether as spaces women lived and worked in or spaces they returned to after work outside the home. An expanded analysis of Marseille’s census records may reveal an exodus of men in other Sections of the city, and the larger impact of the revolution on women’s control of their everyday living environment. Interactive mapping enhances the ability to display, compare, and analyze women’s influence and control of their household space whether as property owners, principal lessees, or renters; and, with further research and analysis, census records will add to our understanding of women’s socioeconomic and geopolitical environments and influence in revolutionary Marseille.

Thank you to the reviewers and editors for their guidance and useful suggestions. Additional thanks to colleagues Marisela Chavez, Anne Choi, Jane Dabel, and Donna Nicol for their feedback. Michelle Richards created static and digital interactive maps. Maps were created using QGIS®, a project of the Open Source Geospatial Foundation (OSGeo). Please visit www.qgis.org. ArcGIS is the intellectual property of Esri and is used herein under license. Copyright ©Esri. All rights reserved. For more information about Esri® software, please visit www.esri.com.

Laura Talamante, “Creating the Republican Family: Political and Social Transformation and the Revolutionary Family Tribunal,” Proceedings of the Western Society for French History, vol. 38 (2010): 143-162; Susanne Desan, The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); Margaret Darrow, Family, Class and Inheritance in Southern France, 1775–1825 (Princeton University Press, 1989); Roderick Phillips, Family Breakdown in Late Eighteenth-Century France: Divorces in Rouen 1792–1803 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980) and Putting Asunder: A History of Divorce in Western Society (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Elaine Kruse, “Divorce in Paris, 1792–1804: Window on a Society in Crisis” (PhD diss., University of Iowa, 1983); Dominique Dessertine, Divorcer à Lyon sous la Révolution et l'Empire, (Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1981); Roderick Phillips, Family Breakdown in Eighteenth-Century France: Rouen, 1780-1800 (Oxford University Press, 1980).

Laura Talamante, “Mapping Women’s Everyday Lives in Revolutionary Marseille,” Life in Revolutionary France, edited by Jennifer Heuer and Mette Harder (London, UK: Bloomsbury Press, 2020), 51-79. See interactive map at https://drlauratalamante.com/marseille-mapping-women-politics/.

Liana Vardi, “The Abolition of the Guilds during the French Revolution,” French Historical Studies 15, no. 4 (1989): 704-717.

Georges Hanne’s study, “L'enregistrement des occupations à l'épreuve du genre: Toulouse, vers 1770-1821,” notes although there were other lists prior to the Revolution for determining occupations, “the census undertaken during the Revolution and systemized during the Restoration” allow for better numerization of occupations and for better understanding of individual social characteristics. Prior to the Revolution, tax records in the form of capitation lists provide data on men. See Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine 54, no. 1 (2007): 75. Julia Landweber has also made me aware that French census undertakings pre-date the Revolution in French colonial lands, Western Society for French History, Forty-Seventh Annual Meeting, Bozeman, MT, 5 October 2019.

Michel Vovelle, “Le Sans-culotte marseillais” Histoire & Mesure, 1, no. 1 (1986): 75-95.

Census records surveyed range in size from approximately 600 to 4000 individuals recorded with calculations from 245 to 1194 heads of household. Three Sections had close to 900 heads of household.

Michael Kennedy, The Jacobin Club of Marseilles, 1790-1794 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1973), 6; William Scott, Terror and Repression in Revolutionary Marseilles (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 7; Alfred Fierro, Historical Dictionary of Paris (Lanham: Scarecrow, 1998), 238.

Rolf Gehrman, “Women as Heads of Households in Germany and France: Evidence from the 1846 censuses,” Revista de historiografía 26 (2017): 167.

Hannah Callaway, “Emigration, Landlords, and Tenants in Revolutionary Paris,” in Life in Revolutionary France, edited by Jennifer Heuer and Mette Harder (London, UK: Bloomsbury Press, 2020), 86-87.

Julie Hardwick, “Women ‘Working’ the Law: Gender, Authority, and Legal Process in Early Modern France,” Journal of Women's History 9, no. 3, (1997): 29.

James B. Collins, “Women and the Birth of Modern Consumer Capitalism,” in Women and Work in Eighteenth-Century France, eds. Daryl M. Hafter and Nina Kushner (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015), 155-159.

Nancy Locklin, “Women and Work Identity,” in Women and Work in Eighteenth-Century France, eds. Daryl M. Hafter and Nina Kushner (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015), 34-35.

Historical map of Marseille, 1791. "Plan routier de la ville et faubourg de Marseille/Levé par Campen en 1791; Et Gravé par Denis Laurent en 1792" courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale.

The latter distinction is counting retired farmers as heads of households. Gehrman, 174.

Deborah Simonton, “Widows and Wenches: Single Women in Eighteenth-century Urban Economies,” in Female Agency in the Urban Economy: Gender in European Towns, 1640-1830, ed. Deborah Simonton and Anne Montenach (New York: Routledge, 2013), 94. Total married heads of households, including male and female married heads of households equals 2,179 while total number of heads of households equals 5,048.

Archives départementales de Bouches-du-Rhône (hereafter AD, BdR), L 1982. Section 1, isle 2, maison 14.

AD, BdR, L1982, Section 1, isle 1, maison 68 and isle 1, maison 64, respectively.

James B. Collins, “The Economic Role of Women in Seventeenth-Century France,” French Historical Studies 16, no. 2 (1989): 464.

Sofia Ling, Karin Hassan Jansson, Marie Lennersand, Christopher Pihl, and Maria Ågren, “Marriage and Work: Intertwined Sources of Agency and Authority,” in Making a Living, Making a Difference: Gender and Work in Early Modern European Society (Oxford, UK: Oxford University, 2017), 81-82.

Archives municipale de Marseille (hereafter AMdM), Section 8, 2 F 10.

Nancy Locklin, “‘Til Death Parts Us: Women’s Domestic Partnerships in Eighteenth-Century Brittany,” Journal of Women’s History 23, no. 4, (2011): 38-39.

Julie Hardwick, Sex in an Old Regime City (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press 2020), 52-53. Kindle Edition.

Alan Forrest, Napoleon’s Men: The Soldiers of the Revolution and Empire (London, UK: Bloomsbury Press, 2006).

Her husband and two daughters are listed after her name, with a notation that her husband was maimed. AMdM, 2 F 13, isle 373, maison 20.

AMdM, 1 G 1 1791-92, rue Paradis, isle 72, maison 10 and rue de Rome, isle 67, maison 4, respectively.

AMdM, 1 G 1 1791-92. She is listed as a journalière, living in Section 4, rue de St. Joseph, maison 315, numero 7.

Collins highlights that “tax rolls show the percentage of taxable hearths headed by women and the substantial regional differences in that percentage.” From the mid-sixteenth century through the seventeenth century, “[t]he rolls, and other records, demonstrate that women ran some 10 to 20 percent of all seventeenth-century French enterprises, including farms. These businesswomen included widows of quite substantial means, independent married women, and a few single women.” “The Economic Role of Women,” 439.